Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (/ˈɑːrtɪmɪs/; Greek: Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity.[1][2] She was heavily identified with Selene, the Moon, and Hecate, another Moon goddess, and was thus regarded as one of the most prominent lunar deities in mythology, alongside the aforementioned two.[3] She would often roam the forests of Greece, attended by her large entourage, mostly made up of nymphs, some mortals, and hunters. The goddess Diana is her Roman equivalent.

| Artemis | |

|---|---|

Goddess of nature, childbirth, wildlife, the Moon, the hunt, sudden death, animals, virginity, young women, and archery | |

| Member of the Twelve Olympians | |

| |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Planet | Moon |

| Animals | deer, serpent, dog, boar, goat, bear, quail, buzzard, guineafowl |

| Symbol | bow and arrows, crescent moon, animal pelts, spear, knives, torch, lyre, amaranth |

| Tree | cypress, palm, walnut |

| Mount | A golden chariot driven by four golden-horned deer |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Parents | Zeus and Leto |

| Siblings | Apollo (twin), Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Ares, Athena, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Diana |

| Etruscan equivalent | Artume |

| Hinduism equivalent | Bhadra |

| Canaanite equivalent | Kotharat |

| Egyptian equivalent | Bastet |

| Zoroastrian equivalent | Drvaspa |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

|

_-_Napoli_MAN_111441.jpg.webp)

In Greek tradition, Artemis is the daughter of the sky god and king of gods Zeus and Leto, and the twin sister of Apollo. In most accounts, the twins are the products of an extramarital liaison. For this, Zeus' wife Hera forbade Leto from giving birth anywhere on land. Only the island of Delos gave refuge to Leto, allowing her to give birth to her children. Usually, Artemis is the twin to be born first, who then proceeds to assist Leto in the birth of the second child, Apollo. Like her brother, she was a kourotrophic (child-nurturing) deity, that is the patron and protector of young children, especially young girls, and women, and was believed to both bring disease upon women and children and relieve them of it. Artemis was worshipped as one of the primary goddesses of childbirth and midwifery along with Eileithyia and Hera. Much like Athena and Hestia, Artemis preferred to remain a maiden goddess and was sworn never to marry, and was thus one of the three Greek virgin goddesses, over whom the goddess of love and lust, Aphrodite, had no power whatsoever.[4]

In myth and literature, Artemis is presented as a hunting goddess of the woods, surrounded by her followers, who is not to be crossed. In the myth of Actaeon, when the young hunter sees her bathing naked, he is transformed into a deer by the angered goddess, and is then devoured by his own hunting dogs who do not recognize their own master. In the story of Callisto, the girl is driven away from Artemis' company after breaking her vow of virginity, having lain with and been impregnated by Zeus. In certain versions, Artemis is the one to turn Callisto into a bear, or even kill her, for her insolence.

In the Epic tradition, Artemis halted the winds blowing the Greek ships during the Trojan War, stranding the Greek fleet in Aulis, after King Agamemnon, the leader of the expedition, shot and killed her sacred deer. Artemis demanded the sacrifice of Iphigenia, Agamemnon's young daughter, as compensation for her slain deer. In most versions, when Iphigenia is led to the altar to be offered as a sacrifice, Artemis pities her and takes her away, leaving another deer in her place. In the war that followed, Artemis along with her twin brother and mother supported the Trojans against the Greeks, and challenged Hera into battle.

Artemis was one of the most widely venerated of the Ancient Greek deities, her worship spread throughout ancient Greece, with her multiple temples, altars, shrines, and local veneration found everywhere in the ancient world. Her great temple at Ephesus was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, before it was burnt to the ground. Artemis' symbols included a bow and arrow, a quiver, and hunting knives, and the deer and the cypress were sacred to her. Diana, her Roman equivalent, was especially worshipped on the Aventine Hill in Rome, near Lake Nemi in the Alban Hills, and in Campania.[5]

Etymology

The name Artemis (noun, feminine) is of unknown or uncertain etymology,[6][7] although various sources have been proposed. R. S. P. Beekes suggested that the e/i interchange points to a Pre-Greek origin.[8] Artemis was venerated in Lydia as Artimus.[9] Georgios Babiniotis, while accepting that the etymology is unknown, also states that the name is already attested in Mycenean Greek and is possibly of Pre-Greek origin.[7]

The name may be related to Greek árktos "bear" (from PIE *h₂ŕ̥tḱos), supported by the bear cult the goddess had in Attica (Brauronia) and the Neolithic remains at the Arkoudiotissa Cave, as well as the story of Callisto, which was originally about Artemis (Arcadian epithet kallisto);[10] this cult was a survival of very old totemic and shamanistic rituals and formed part of a larger bear cult found further afield in other Indo-European cultures (e.g., Gaulish Artio). It is believed that a precursor of Artemis was worshipped in Minoan Crete as the goddess of mountains and hunting, Britomartis. While connection with Anatolian names has been suggested,[11][12] the earliest attested forms of the name Artemis are the Mycenaean Greek 𐀀𐀳𐀖𐀵, a-te-mi-to /Artemitos/ (gen.) and 𐀀𐀴𐀖𐀳, a-ti-mi-te /Artimitei/ (dat.), written in Linear B at Pylos.[13][8]

According to J. T. Jablonski, the name is also Phrygian and could be "compared with the royal appellation Artemas of Xenophon.[14] Charles Anthon argued that the primitive root of the name is probably of Persian origin from *arta, *art, *arte, all meaning "great, excellent, holy", thus Artemis "becomes identical with the great mother of Nature, even as she was worshipped at Ephesus".[14] Anton Goebel "suggests the root στρατ or ῥατ, "to shake", and makes Artemis mean the thrower of the dart or the shooter".[15]

Ancient Greek writers, by way of folk etymology, and some modern scholars, have linked Artemis (Doric Artamis) to ἄρταμος, artamos, i.e. "butcher"[16][17] or, like Plato did in Cratylus, to ἀρτεμής, artemḗs, i.e. "safe", "unharmed", "uninjured", "pure", "the stainless maiden".[15][14][18] A. J. Van Windekens tried to explain both ἀρτεμής and Artemis from ἀτρεμής, atremḗs, meaning "unmoved, calm; stable, firm" via metathesis.[19][20]

Description

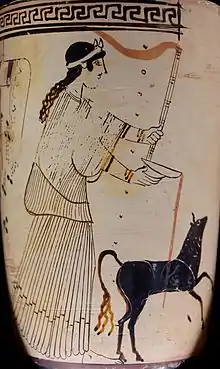

Artemis is presented as a goddess who delights in hunting and punishes harshly those who cross her. Artemis' wrath is proverbial, and represents the hostility of wild nature to humans.[2] Homer calls Artemis πότνια θηρῶν, "the mistress of animals", a titled associated with representations in art going back as far as the Bronze Age, showing a woman between a pair of animals.[21]

The ancient Greeks called 'potnia theron' this sort of representation of the goddess; on a Greek vase from circa 570 BCE a winged Artemis stands between a spotted panther and a deer.[22] Another almost formulaic epithet used by poets to describe her is ἰοχέαιρα iokheaira, "she who shoots arrows", often translated as "she who delights in arrows" or "she who showers arrows".[23] She is often called Artemis Chryselacatos, "Artemis of the golden shafts". The Homeric Hymn 27 to Artemis paints this picture of the goddess:

I sing of Artemis, whose shafts are of gold, who cheers on the hounds, the pure maiden, shooter of stags, who delights in archery, own sister to Apollo with the golden sword. Over the shadowy hills and windy peaks she draws her golden bow, rejoicing in the chase, and sends out grievous shafts. The tops of the high mountains tremble and the tangled wood echoes awesomely with the outcry of beasts: earthquakes and the sea also where fishes shoal.

In spite of her status as a virgin who avoided potential lovers, there are multiple references to Artemis' beauty and erotic aspect;[25] in the Odyssey, Odysseus compares Nausicaa to Artemis in terms of appearance when trying to win her favor, Libanius, when praising the city of Antioch, wrote that Ptolemy was smitten by the beauty of (the statue of) Artemis;[25] whereas her mother Leto often took pride in her daughter's beauty.[26][27]

She has several stories surrounding her where men such as Actaeon, Orion, and Alpheus tried to couple with her forcibly only to be thwarted or killed. Ancient poets note Artemis' height and imposing stature, as she stands taller and more impressive than all the nymphs accompanying her.[27][28] In Athens and Tegea, she was worshipped as Artemis Calliste, "the most beautiful".[29] She was generally represented as healthy, strong, and active, bearing quiver and bow and accompanied by a dog.[30]

Mythology

Leto bore Apollo and Artemis, delighting in arrows,

Both of lovely shape like none of the heavenly gods,

As she joined in love to the Aegis-bearing ruler.— Hesiod, Theogony, lines 918–920 (written in the 7th century BCE)

Birth

Various conflicting accounts are given in Greek mythology regarding the birth of Artemis and Apollo, her twin brother. However, in terms of parentage, all accounts agree that she was the daughter of Zeus and Leto and that she was the twin sister of Apollo. In some sources, she is born at the same time as Apollo, in others, earlier or later.[5]

Although traditionally stated to be twins, the author of The Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo (the oldest extant account of Leto's wandering and birth of her children) is only concerned with the birth of Apollo, and sidelines Artemis;[31] in fact in the Homeric Hymn they are not stated to be twins at all, and it is a slightly later poet, Pindar, who speaks of a single pregnancy.[32] The two earliest poets, Homer and Hesiod, confirm Artemis and Apollo's status as full siblings born to the same mother and father, but neither explicitly makes them twins.[33]

According to Callimachus, Hera, angry with her husband Zeus for impregnating Leto, forbade her from giving birth on either terra firma (the mainland) or on an island, but the island of Delos disobeyed and allowed Leto to give birth there. According to the Homeric Hymn to Artemis, however, the island where she and her twin were born was Ortygia.[34][35] In ancient Cretan history Leto was worshipped at Phaistos and, in Cretan mythology, Leto gave birth to Apollo and Artemis on the islands known today as Paximadia.

A scholium of Servius on Aeneid iii. 72 accounts for the island's archaic name Ortygia[36] by asserting that Zeus transformed Leto into a quail (ortux) in order to prevent Hera from finding out about his infidelity, and Kenneth McLeish suggested further that in quail form Leto would have given birth with as few birth-pains as a mother quail suffers when it lays an egg.[37]

The myths also differ as to whether Artemis was born first, or Apollo. Most stories depict Artemis as firstborn, becoming her mother's midwife upon the birth of her brother Apollo. Servius, a late fourth/early fifth-century grammarian, wrote that Artemis was born first because at first it was night, whose instrument is the moon, which Artemis represents, and then day, whose instrument is the sun, which Apollo represents.[38] Pindar however writes that both twins shone like the sun when they came into the bright light.[39]

Childhood

The childhood of Artemis is not fully related to any surviving myth. A poem by Callimachus to the goddess "who amuses herself on mountains with archery" imagines a few vignettes of a young Artemis. While sitting on the knee of her father, she asks him to grant her ten wishes:

- to always remain a virgin

- to have many names to set her apart from her brother Phoebus (Apollo)

- to have a bow and arrow made by the Cyclopes

- to be the Phaesporia or Light Bringer

- to have a short, knee-length tunic so she could hunt

- to have 60 "daughters of Okeanos", all nine years of age, to be her choir

- to have 20 Amnisides Nymphs as handmaidens to watch her hunting dogs and bow while she rested

- to rule all the mountains

- to be assigned any city, and only to visit when called by birthing mothers

- to have the ability to help women in the pains of childbirth.[40]

Artemis believed she had been chosen by the Fates to be a midwife, particularly as she had assisted her mother in the delivery of her twin brother Apollo.[41] All of her companions remained virgins, and Artemis closely guarded her own chastity. Her symbols included the golden bow and arrow, the hunting dog, the stag, and the moon.

Callimachus then tells[42] how Artemis spent her girlhood seeking out the things she would need to be a huntress, and how she obtained her bow and arrows from the isle of Lipara, where Hephaestus and the Cyclopes worked. While Oceanus' daughters were initially fearful, the young Artemis bravely approached and asked for a bow and arrows. He goes on to describe how she visited Pan, god of the forest, who gave her seven female and six male hounds. She then captured six golden-horned deer to pull her chariot. Artemis practiced archery first by shooting at trees and then at wild game.[42]

Relations with men

_in_the_National_Archaeological_Museum_of_Athens_on_22_July_2018.jpg.webp)

The river god Alpheus was in love with Artemis, but as he realized he could do nothing to win her heart, he decided to capture her. When Artemis and her companions at Letrenoi go to Alpheus, she becomes suspicious of his motives and covers her face with mud so he does not recognize her. In another story, Alphaeus tries to rape Artemis' attendant Arethusa. Artemis pities the girl and saves her, transforming her into a spring in the temple Artemis Alphaea in Letrini, where the goddess and her attendant drink.

Bouphagos, son of the Titan Iapetus, sees Artemis and thinks about raping her. Reading his sinful thoughts, Artemis strikes him down at Mount Pholoe.

Daphnis was a young boy, a son of Hermes, who was accepted by and became a follower of the goddess Artemis; Daphnis would often accompany her in hunting and entertain her with his singing of pastoral songs and playing of the panpipes.[43]

Artemis taught a man, Scamandrius, how to be a great archer, and he excelled in the use of a bow and arrow with her guidance.[44]

Broteas was a famous hunter who refused to honour Artemis, and boasted that nothing could harm him, not even fire. Artemis then drove him mad, causing him to walk into fire, ending his life.[45]

According to Antoninus Liberalis, Siproites was a Cretan who was metamorphized into a woman by Artemis, for, while hunting, seeing the goddess bathing.[46]

Actaeon

Multiple versions of the Actaeon myth survive, though many are fragmentary. The details vary but at the core, they involve the great hunter Actaeon whom Artemis turns into a stag for a transgression, and who is then killed by hunting dogs.[47][48] Usually, the dogs are his own, but no longer recognize their master. Occasionally they are said to be the hounds of Artemis.

Various tellings diverge in terms of the hunter's transgression: sometimes merely seeing the virgin goddess naked, sometimes boasting he is a better hunter than she,[49] or even merely being a rival of Zeus for the affections of Semele. Apollodorus, who records the Semele version, notes that the ones with Artemis are more common.[50] According to Lamar Ronald Lacey's The Myth of Aktaion: Literary and Iconographic Studies, the standard modern text on the work, the most likely original version of the myth portrays Actaeon as the hunting companion of the goddess who, seeing her naked in her sacred spring, attempts to force himself on her. For this hubris, he is turned into a stag and devoured by his own hounds. However, in some surviving versions, Actaeon is a stranger who happens upon Artemis.

A single line from Aeschylus's now lost play Toxotides ("female archers") is among the earlier attestations of Actaeon's myth, stating that "the dogs destroyed their master utterly", with no confirmation of Actaeon's metamorphosis or the god he offended (but it is heavily implied to be Artemis, due to the title).[51] Ancient artwork depicting the myth of Actaeon predate Aeschylus.[52]

Euripides, coming in a bit later, wrote in the Bacchae that Actaeon was torn to shreds and perhaps devoured by his "flesh-eating" hunting dogs when he claimed to be a better hunter than Artemis.[53] Like Aeschylus, he does not mention Actaeon being deer-shaped when that happens. Callimachus writes that Actaeon chanced upon Artemis bathing in the woods, and she caused him to be devoured by his own hounds for the sacrilege, and he makes no mention of transformation into a deer either.[54]

Diodorus Siculus wrote that Actaeon dedicated his prizes in hunting to Artemis, proposed marriage to her, and even tried to forcefully consummate said "marriage" inside the very sacred temple of the goddess; for this he was given the form "of one of the animals which he was wont to hunt", and then torn to shreds by his hunting dogs. Diodorus also mentioned the alternative of Actaeon claiming to be a better hunter than the goddess of the hunt.[55] Hyginus also mentions Actaeon attempting to rape Artemis when he finds her bathing naked, and her transforming him into the doomed deer.[56]

Apollodorus wrote that when Actaeon saw Artemis bathing, she turned him into a deer on the spot, and intentionally drove his dogs into a frenzy so that they would kill and devour him. Afterward, Chiron built a sculpture of Actaeon to comfort his dogs in their grief, as they could not find their master no matter how much they looked for him.[50]

According to the Latin version of the story told by the Roman Ovid, Actaeon was a hunter who after returning home from a long day's hunting in the woods, he stumbled upon Artemis and her retinue of nymphs bathing in her sacred grotto. The nymphs, panicking, rushed to cover Artemis' naked body with their own, as Artemis splashed some water on Actaeon, saying he was welcome to share with everyone the tale of seeing her without any clothes as long as he could share it at all. Immediately, he was transformed into a deer, and in panic ran away. But he did not go far, as he was hunted down and eventually caught and devoured by his own fifty hunting dogs, who could not recognize their own master.[57][58]

Pausanias says that Actaeon saw Artemis naked and that she threw a deerskin on him so that his hounds would kill him, in order to prevent him from marrying Semele.[59]

Niobe

_from_the_%22Rospigliosi_type%22%252C_Roman_copy_of_the_1st%E2%80%932nd_centuries_AD_after_a_Hellenistic_original%252C_Louvre_Museum_(7462739810).jpg.webp)

The story of Niobe, queen of Thebes and wife of Amphion, who blasphemously boasted of being superior to Leto, is very old; Homer knew of it, who wrote that Niobe had given birth to twelve children, equally divided in six sons and six daughters (the Niobids). Other sources speak of fourteen children, seven sons, and seven daughters. Niobe claimed of being a better mother than Leto, for having more children than Leto's own two, "but the two, though they were only two, destroyed all those others."[60]

Leto was not slow to catch up on that and grew angry at the queen's hubris. She summoned her children and commanded them to avenge the slight against her. Swiftly Apollo and Artemis descended on Thebes. While the sons were hunting in the woods, Apollo crept up on them and slew all seven with his silver bow. The dead bodies were brought to the palace. Niobe wept for them, but did not relent, saying that even now she was better than Leto, for she still had seven children, her daughters.[61]

On cue, Artemis then started shooting the daughters one by one. Right as Niobe begged for her youngest one to be spared, Artemis killed that last one.[62] Niobe cried bitter tears, and was turned into a rock. Amphion, at the sight of his dead sons, killed himself. The gods themselves entombed them. In some versions, Apollo and Artemis spared a single son and daughter each, for they prayed to Leto for help; thus Niobe had as many children as Leto did, but no more.[63]

Orion

Orion was Artemis' hunting companion; after giving up on trying to find Oenopion, Orion met Artemis and her mother Leto, and joined the goddess in hunting. A great hunter himself, he bragged that he would kill every beast on earth. Gaia, the earth, was not too pleased to hear that, and sent a giant scorpion to sting him. Artemis then transferred him into the stars as the constellation Orion.[64] In one version Orion died after pushing Leto out of the scorpion's way.[65]

In another version, Orion tries to violate Opis,[66] one of Artemis' followers from Hyperborea, and Artemis kills him.[67] In a version by Aratus, Orion grabs Artemis' robe and she kills him in self-defense.[68] Other writers have Artemis kill him for trying to rape her or one of her attendants.[69]

Istrus wrote a version in which Artemis fell in love with Orion, apparently the only person she ever did. She meant to marry him, and no talk from her brother Apollo would change her mind. Apollo then decided to trick Artemis, and while Orion was off swimming in the sea, he pointed at him (barely a spot in the horizon) and wagered that Artemis could not hit that small "dot". Artemis, ever eager to prove she was the better archer, shot Orion, killing him. She then placed him among the stars.[70]

In Homer's Iliad, the goddess of the dawn Eos seduces Orion, angering the gods who did not approve of immortal goddesses taking mortal men for lovers, causing Artemis to shoot and kill him on the island of Ortygia.[71]

Callisto

Callisto, the daughter of Lycaon, King of Arcadia,[72] was one of Artemis' hunting attendants, and, as a companion of Artemis, took a vow of chastity.[73]

According to Hesiod in his lost poem Astronomia, Zeus appeared to Callisto, and seduced her, resulting in her becoming pregnant. Though she was able to hide her pregnancy for a time, she was soon found out while bathing. Enraged, Artemis transformed Callisto into a bear, and in this form she gave birth to her son Arcas. Both of them were then captured by shepherds and given to Lycaon, and Callisto thus lost her child. Sometime later, Callisto "thought fit to go into" a forbidden sanctuary of Zeus, and was hunted by the Arcadians, her son among them.[74] When she was about to be killed, Zeus saved her by placing her in the heavens as a constellation of a bear.[75]

In his De Astronomica, Hyginus, after recounting the version from Hesiod,[76] presents several other alternative versions. The first, which he attributes to Amphis, says that Zeus seduced Callisto by disguising himself as Artemis during a hunting session, and that when Artemis found out that Callisto was pregnant, she replied saying that it was the goddess's fault, causing Artemis to transform her into a bear. This version also has both Callisto and Arcas placed in the heavens, as the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor.[77]

Hyginus then presents another version in which, after Zeus lay with Callisto, it was Hera who transformed her into a bear. Artemis later, while hunting, kills the bear, and "later, on being recognized, [Callisto] was placed among the stars".[78] Hyginus also gives another version, in which Hera tries to catch Zeus and Callisto in the act, causing Zeus to transform her into a bear. Hera, finding the bear, points it out to Artemis, who is hunting; Zeus, in panic, places Callisto in the heavens as a constellation.[79]

Ovid gives a somewhat different version: Zeus seduced Callisto once again disguised as Artemis, but she seems to realise that it is not the real Artemis,[80] and she thus does not blame Artemis when, during bathing, she is found out. Callisto is, rather than being transformed, simply ousted from the company of the huntresses, and she thus gives birth to Arcas as a human. Only later is she transformed into a bear, this time by Hera. When Arcas, fully grown, is out hunting, he nearly kills his mother, who is saved only by Zeus placing her in the heavens.[81]

In the Bibliotheca, a version is presented in which Zeus raped Callisto, "having assumed the likeness, as some say, of Artemis, or, as others say, of Apollo". He then turned her into a bear himself so as to hide the event from Hera. Artemis then shot the bear, either upon the persuasion of Hera, or out of anger at Callisto for breaking her virginity.[82] Once Callisto was dead, Zeus made her into a constellation, took the child, named him Arcas, and gave him to Maia, who raised him.[83]

Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, presents another version, in which, after Zeus seduced Callisto, Hera turned her into a bear, which Artemis killed to please Hera.[84] Hermes was then sent by Zeus to take Arcas, and Zeus himself placed Callisto in the heavens.[85]

Minor myths

When Zeus' gigantic son Tityos tried to rape Leto, she called out to her children for help, and both Artemis and Apollo were quick to respond by raining down their arrows on Tityos, killing him.[86]

Chione was a princess of Pokis. She was beloved by two gods, Hermes and Apollo, and boasted that she was more beautiful than Artemis because she had made two gods fall in love with her at once. Artemis was furious and killed Chione with an arrow,[87] or struck her mute by shooting off her tongue. However, some versions of this myth say Apollo and Hermes protected her from Artemis' wrath.

Artemis saved the infant Atalanta from dying of exposure after her father abandoned her. She sent a female bear to nurse the baby, who was then raised by hunters. In some stories, Artemis later sent a bear to injure Atalanta because others claimed Atalanta was a superior hunter. Among other adventures, Atalanta participated in the Calydonian boar hunt, which Artemis had sent to destroy Calydon because King Oeneus had forgotten her at the harvest sacrifices.

In the hunt, Atalanta drew the first blood and was awarded the prize of the boar's hide. She hung it in a sacred grove at Tegea as a dedication to Artemis. Meleager was a hero of Aetolia. King Oeneus ordered him to gather heroes from all over Greece to hunt the Calydonian boar. After the death of Meleager, Artemis turns his grieving sisters, the Meleagrids, into guineafowl that Artemis favoured.

In Nonnus' Dionysiaca, Aura, the daughter of Lelantos and Periboia, was a companion of Artemis.[88] When out hunting one day with Artemis, she asserts that the goddess's voluptuous body and breasts are too womanly and sensual, and doubts her virginity, arguing that her own lithe body and man-like breasts are better than Artemis' and a true symbol of her own chastity. In anger, Artemis asks Nemesis for help to avenge her dignity. Nemesis agrees, telling Artemis that Aura's punishment will be to lose her virginity, since she dared question that of Artemis.

Nemesis then arranges for Eros to make Dionysus fall in love with Aura. Dionysus intoxicates Aura and rapes her as she lies unconscious, after which she becomes a deranged killer. While pregnant, she tries to kill herself or cut open her belly, as Artemis mocks her over it. When she bore twin sons, she ate one, while the other, Iacchus, was saved by Artemis.

The twin sons of Poseidon and Iphimedeia, Otos and Ephialtes, grew enormously at a young age. They were aggressive and skilled hunters who could not be killed except by each other. The growth of the Aloadae never stopped, and they boasted that as soon as they could reach heaven, they would kidnap Artemis and Hera and take them as wives. The gods were afraid of them, except for Artemis who captured a fine deer that jumped out between them. In another version of the story, she changed herself into a doe and jumped between them.[5]

The Aloadae threw their spears and so mistakenly killed one another. In another version, Apollo sent the deer into the Aloadae's midst, causing their accidental killing of each other.[5] In another version, they start pilling up mountains to reach Mount Olympus in order to catch Hera and Artemis, but the gods spot them and attack. When the twins had retreated the gods learnt that Ares has been captured. The Aloadae, not sure about what to do with Ares, lock him up in a pot. Artemis then turns into a deer and causes them to kill each other.

In some versions of the story of Adonis, Artemis sent a wild boar to kill him as punishment for boasting that he was a better hunter than her.[89] In other versions, Artemis killed Adonis for revenge. In later myths, Adonis is a favorite of Aphrodite, who was responsible for the death of Hippolytus, who had been a hunter of Artemis. Therefore, Artemis killed Adonis to avenge Hippolytus's death. In yet another version, Adonis was not killed by Artemis, but by Ares as punishment for being with Aphrodite.[90]

Polyphonte was a young woman who fled home in pursuit of a free, virginal life with Artemis, as opposed to the conventional life of marriage and children favoured by Aphrodite. As a punishment, Aphrodite cursed her, causing her to mate and have children with a bear. Artemis, seeing that, was disgusted and sent a horde of wild animals against her, causing Polyphonte to flee to her father's house. Her resulting offspring, Agrius and Oreius, were wild cannibals who incurred the hatred of Zeus. Ultimately the entire family was transformed into birds who became ill portents for mankind.[91]

Coronis was a princess from Thessaly who became the lover of Apollo and fell pregnant. While Apollo was away, Coronis began an affair with a mortal man named Ischys. When Apollo learnt of this, he sent Artemis to kill the pregnant Coronis, or Artemis had the initiative to kill Coronis on her own accord for the insult done against her brother. The unborn child, Asclepius, was later removed from his dead mother's womb.[92]

When the queen of Kos Euthemia ceased to worship Artemis, she shot her with an arrow; Persephone then snatched the still-living Euthemia and brought her to the Underworld.[93]

Trojan War

Artemis may have been represented as a supporter of Troy because her brother Apollo was the patron god of the city, and she herself was widely worshipped in western Anatolia in historical times. Artemis plays a significant role in the war; like Leto and Apollo, Artemis took the side of the Trojans. At the beginning of the Greek's journey to Troy, Artemis punished Agamemnon after he killed a sacred stag in a sacred grove and boasted that he was a better hunter than the goddess.[94]

When the Greek fleet was preparing at Aulis to depart for Troy to commence the Trojan War, Artemis becalmed the winds. The seer Calchas erroneously advised Agamemnon that the only way to appease Artemis was to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia. In some version of the myth, Artemis then snatched Iphigenia from the altar and substituted a deer; in others, Artemis allowed Iphigenia to be sacrificed. In versions where Iphigenia survived, a number of different myths have been told about what happened after Artemis took her; either she was brought to Tauros and led the priests there, or she became Artemis' immortal companion.[95]

Aeneas was also helped by Artemis, Leto, and Apollo. Apollo found him wounded by Diomedes and lifted him to heaven. There, the three deities secretly healed him in a great chamber.

During the theomachy, Artemis found herself standing opposite of Hera, on which a scholium to the Iliad wrote that they represent the moon versus the air around the earth.[96] Artemis chided her brother Apollo for not fighting Poseidon and told him never to brag again; Apollo did not answer her. An angry Hera berated Artemis for daring to fight her:

How now art thou fain, thou bold and shameless thing, to stand forth against me? No easy foe I tell thee, am I, that thou shouldst vie with me in might, albeit thou bearest the bow, since it was against women that Zeus made thee a lion, and granted thee to slay whomsoever of them thou wilt. In good sooth it is better on the mountains to be slaying beasts and wild deer than to fight amain with those mightier than thou. Howbeit if thou wilt, learn thou of war, that thou mayest know full well how much mightier am I, seeing thou matchest thy strength with mine.

Hera then grabbed Artemis' hands by the wrists, and holding her in place, beat her with her own bow.[97] Crying, Artemis left her bow and arrows where they lay and ran to Olympus to cry at her father Zeus' knees, while her mother Leto picked up her bow and arrows and followed her weeping daughter.[98]

Worship

Artemis, the goddess of forests and hills, was worshipped throughout ancient Greece.[99] Her best known cults were on the island of Delos (her birthplace), in Attica at Brauron and Mounikhia (near Piraeus), and in Sparta. She was often depicted in paintings and statues in a forest setting, carrying a bow and arrows and accompanied by a deer.

The ancient Spartans used to sacrifice to her as one of their patron goddesses before starting a new military campaign.

Athenian festivals in honor of Artemis included Elaphebolia, Mounikhia, Kharisteria, and Brauronia. The festival of Artemis Orthia was observed in Sparta.

Pre-pubescent and adolescent Athenian girls were sent to the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron to serve the Goddess for one year. During this time, the girls were known as arktoi, or little she-bears. A myth explaining this servitude states that a bear had formed the habit of regularly visiting the town of Brauron, and the people there fed it, so that, over time, the bear became tame. A girl teased the bear, and, in some versions of the myth, it killed her, while, in other versions, it clawed out her eyes. Either way, the girl's brothers killed the bear, and Artemis was enraged. She demanded that young girls "act the bear" at her sanctuary in atonement for the bear's death.[100]

Artemis was worshipped as one of the primary goddesses of childbirth and midwifery along with Eileithyia. Dedications of clothing to her sanctuaries after a successful birth was common in the Classical era.[101] Artemis could be a deity to be feared by pregnant women, as deaths during this time were attributed to her. As childbirth and pregnancy was a very common and important event, there were numerous other deities associated with it, many localized to a particular geographic area, including but not limited to Aphrodite, Hera and Hekate.[101]

It was considered a good sign when Artemis appeared in the dreams of hunters and pregnant women, but a naked Artemis was seen as an ill omen.[102] According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, she assisted her mother in the delivery of her twin.[103] Older sources, such as Homeric Hymn to Delian Apollo (in Line 115), have the arrival of Eileithyia on Delos as the event that allows Leto to give birth to her children. Contradictory is Hesiod's presentation of the myth in Theogony, where he states that Leto bore her children before Zeus’ marriage to Hera with no commentary on any drama related to their birth.

Despite her being primarily known as a goddess of hunting and the wilderness, she was also connected to dancing, music, and song like her brother Apollo; she is often seen singing and dancing with her nymphs, or leading the chorus of the Muses and the Graces at Delphi. In Sparta, girls of marriageable age performed the partheneia (choral maiden songs) in her honor.[104] An ancient Greek proverb, written down by Aesop, went "For where did Artemis not dance?", signifying the goddess' connection to dancing and festivity.[105][106]

During the Classical period in Athens, she was identified with Hekate. Artemis also assimilated Caryatis (Carya).

There was a women's cult at Cyzicus worshiping Artemis, which was called Dolon (Δόλων).[107]

Epithets

| |

| O: bare head of Augustus

ΚΑΙΣΑΡ / ΘΕΟΥ ΥΙΟΣ |

R: Artemis Tauropolos riding bull

ΑΜΦΙΠOΛΕΙΤΩΝ |

| bronze coin struck by Augustus in Amphipolis 31 - 27 BCE; ref.: RPC 1626 | |

As Aeginaea, she was worshipped in Sparta; the name means either huntress of chamois, or the wielder of the javelin (αἰγανέα).[108][109] Also in Sparta, Artemis Lygodesma was worshipped. This epithet means "willow-bound" from the Greek lygos (λυγός, willow) and desmos (δεσμός, bond). The willow tree appears in several ancient Greek myths and rituals.[110] According to Pausanias (3.16.7), a statue of Artemis was found by the brothers Astrabacus and Alopecus under a bush of willows (λύγος), by which it was surrounded in such a manner that it stood upright.[111]

As Artemis Orthia (Ὀρθία, "upright") and was common to the four villages originally constituting Sparta: Limnai, in which it is situated, Pitana, Kynosoura, and Mesoa.

In Athens she was worshipped under the epithet Aristo ("the best").[112]

Also in Athens, she was worshipped as Aristoboule, "the best adviser".

As Artemis Isora also known as Isoria or Issoria, in the temple at the Issorium near lounge of the Crotani (the body of troops named the Pitanatae) near Pitane, Sparta. Pausanias mentions that although the locals refer to her as Artemis Isora, he says "They surname her also Lady of the Lake, though she is not really Artemis hut Britomartis of Crete" [113][114][115]

She was worshipped at Naupactus as Aetole; in her temple in that town, there was a statue of white marble representing her throwing a javelin.[116] This "Aetolian Artemis" would not have been introduced at Naupactus, anciently a place of Ozolian Locris, until it was awarded to the Aetolians by Philip II of Macedon. Strabo records another precinct of "Aetolian Artemos" at the head of the Adriatic.[117] As Agoraea she was the protector of the agora.

As Agrotera, she was especially associated as the patron goddess of hunters. In Athens Artemis was often associated with the local Aeginian goddess, Aphaea. As Potnia Theron, she was the patron of wild animals; Homer used this title. As Kourotrophos, she was the nurse of youths. As Locheia, she was the goddess of childbirth and midwives.

She was sometimes known as Cynthia, from her birthplace on Mount Cynthus on Delos, or Amarynthia from a festival in her honor originally held at Amarynthus in Euboea.

She was sometimes identified by the name Phoebe, the feminine form of her brother Apollo's solar epithet Phoebus. Also due to her connection to the cult of Apollo, she was known under the bynames Daphnaea, Delphinia and Pythia, feminine equivalents of Apollo's epithets.[104][118] Although Apollo's connection to laurels is self-evident, it is not clear why Artemis would bear that epithet, but perhaps it could be because of her statue made of laurel wood.[118]

Alphaea, Alpheaea, or Alpheiusa (Gr. Ἀλφαῖα, Ἀλφεαία, or Ἀλφειοῦσα) was an epithet that Artemis derived from the river god Alpheius, who was said to have been in love with her.[119] It was under this name that she was worshipped at Letrini in Elis,[120][121] and in Ortygia.[122] Artemis Alphaea was associated with the wearing of masks, largely because of the legend that while fleeing the advances of Alpheius, she and her nymphs escaped him by covering their faces.[123]

As Artemis Anaitis, the 'Persian Artemis' was identified with Anahita. As Apanchomene, she was worshipped as a hanged goddess.

In Lusi (Arcadia) she was worshipped as Artemis Hemeresia, "soothing Artemis."[124]

She was also worshiped as Artemis Tauropolos, variously interpreted as "worshipped at Tauris", "pulled by a yoke of bulls", or "hunting bull goddess". A statue of Artemis "Tauropolos" in her temple at Brauron in Attica was supposed to have been brought from the Taurians by Iphigenia. Tauropolia was also a festival of Artemis in Athens. There was a Tauropolion, a temple in a temenos sacred to Artemis Tauropolos, in the north Aegean island of Doliche (now Ikaria). There is a Temple to 'Artemis Tauropolos' (as well as a smaller temple to an unknown goddess about 262 metres (860 feet) south, on the beach) located on the eastern shore of Attica, in the modern town of Artemida. An aspect of the Taurian Artemis was also worshipped as Aricina.

At Castabala in Cilicia there was a sanctuary of Artemis Perasia. Strabo wrote that: "some tell us over and over the same story of Orestes and Tauropolos, asserting that she was called Perasian because she was brought from the other side."[125]

Pausanias at the Description of Greece writes that near Pyrrhichus, there was a sanctuary of Artemis called Astrateias (Ancient Greek: Ἀστρατείας), with an image of the goddess said to have been dedicated by the Amazons.[126] He also wrote that at Pheneus there was a sanctuary of Artemis, which the legend said that it was founded by Odysseus when he lost his mares and when he traversed Greece in search of them, he found them on this site. For this the goddess was called Heurippa (Ancient Greek: Εὑρίππα), meaning horse finder.[127]

One of the epithets of Artemis was Chitone (Ancient Greek: Χιτώνη)[128] or Chitona or Chitonia (Ancient Greek: Χιτώνια).[129] Ancient writers believed that the epithet derived from the chiton that the goddess was wearing as a huntress or from the clothes in which newborn infants were dressed being sacred to her or from the Attic village of Chitone.[130] Syracusans had a dance sacred to the Chitone Artemis.[131] At the Miletus there was a sanctuary of Artemis Chitone and was one of the oldest sanctuaries in the city.[132]

As the goddess of midwives who was called upon during childbirth, Artemis was given a number of epithets such as Eileithyia, Lochia, Eulochia, and Geneteira. Her cult was conflated with that of Eileithyia and Hecate as childbed goddesses.[101] As goddess of music and song, she was called Molpadia and Hymnia ("of the hymns") in Delos.[104]

The epithet Leucophryne (Λευκοφρύνη), derived from the city of Leucophrys. At the Magnesia on the Maeander there was a sanctuary dedicated to her.[133] In addition, the sons of Themistocles dedicated a statue to her at the Acropolis of Athens, because Themistocles had once ruled the Magnesia.[134] Bathycles of Magnesia dedicated a statue of her at Amyclae.[135]

Festivals

Artemis was born on the sixth day of the month Thargelion (around May), which made it sacred for her, as her birthday.[136]

- Festival of Artemis in Brauron, where girls, aged between five and ten, dressed in saffron robes and played at being bears, or "act the bear" to appease the goddess after she sent the plague when her bear was killed.

- Festival of Amarysia is a celebration to worship Artemis Amarysia in Attica. In 2007, a team of Swiss and Greek archaeologists found the ruin of Artemis Amarysia Temple, at Euboea, Greece.[137]

- Festival of Artemis Saronia, a festival to celebrate Artemis in Trozeinos, a town in Argolis. A king named Saron built a sanctuary for the goddess after the goddess saved his life when he went hunting and was swept away by a wave. He held a festival in her honor.[138]

- On the 16th day of Metageitnio (second month on the Athenian calendar), people sacrificed to Artemis and Hecate at Deme in Erchia.[139]

- Kharisteria Festival on 6th day of Boidromion (third month) celebrates the victory of the Battle of Marathon, also known as the Athenian "Thanksgiving".[140]

- Day six of Elaphobolia (ninth month) festival of Artemis the Deer Huntress where she was offered cakes shaped like stags, made from dough, honey and sesame seeds.[141]

- Day 6 or 16 of Mounikhion (tenth month) is a celebration of her as the goddess of nature and animals. A goat was sacrificed to her.[142]

- Day 6 of Thargelion (eleventh month), is the Goddess's birthday, while the seventh was Apollo's.[143]

- A festival for Artemis Diktynna (of the net) was held in Hypsous.

- Laphria, a festival for Artemis in Patrai. The procession starts by setting logs of wood around the altar, each of them 16 cubits long. On the altar, within the circle, the driest wood is placed. Just before the festival, a smooth ascent to the altar is built by piling earth upon the altar steps. The festival begins with a splendid procession in honor of Artemis, and the maiden officiating as priestess rides last in the procession upon a chariot yoked to four deer, Artemis' traditional mode of transport (see below). However, the sacrifice is not offered until the next day.

- In Orchomenus, a sanctuary was built for Artemis Hymnia where her festival was celebrated every year.

Attributes

Virginity

An important aspect of Artemis' persona and worship was her virginity, which may seem contradictory given her role as a goddess associated with childbirth. It is likely that the idea of Artemis as a virgin goddess is related to her primary role as a huntress. Hunters traditionally abstained from sex prior to the hunt as a form of ritual purity and out of a belief that the scent would scare off potential prey. The ancient cultural context in which Artemis' worship emerged also held that virginity was a prerequisite to marriage, and that a married woman became subservient to her husband.[144]

In this light, Artemis' virginity is also related to her power and independence. Rather than a form of asexuality, it is an attribute that signals Artemis as her own master, with power equal to that of male gods. It is also possible that her virginity represents a concentration of fertility that can be spread among her followers, in the manner of earlier mother goddess figures. However, some later Greek writers did come to treat Artemis as inherently asexual and as an opposite to Aphrodite.[144] Furthermore, some have described Artemis along with the goddesses Hestia and Athena as being asexual, this is mainly supported by the fact that in the Homeric Hymns, 5, To Aphrodite, where Aphrodite is described as having "no power" over the three goddesses.[145]

As a mother goddess

Despite her virginity, both modern scholars and ancient commentaries have linked Artemis to the archetype of the mother goddess. Artemis was traditionally linked to fertility and was petitioned to assist women with childbirth. According to Herodotus, the Greek playwright Aeschylus identified Artemis with Persephone as a daughter of Demeter. Her worshipers in Arcadia also traditionally associated her with Demeter and Persephone. In Asia Minor, she was often conflated with local mother goddess figures, such as Cybele, and Anahita in Iran.[144]

However, the archetype of the mother goddess was not highly compatible with the Greek pantheon, and though the Greeks had adopted the worship of Cybele and other Anatolian mother goddesses as early as the 7th century BCE, she was not directly conflated with any Greek goddesses. Instead, bits and pieces of her worship and aspects were absorbed variously by Artemis, Aphrodite, and others as Eastern influence spread.[144]

As the Lady of Ephesus

At Ephesus in Ionia, Turkey, her temple became one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It was probably the best-known center of her worship except for Delos. There the Lady whom the Ionians associated with Artemis through interpretatio graeca was worshipped primarily as a mother goddess, akin to the Phrygian goddess Cybele, in an ancient sanctuary where her cult image depicted the "Lady of Ephesus" adorned with multiple large beads. Excavation at the site of the Artemision in 1987–88 identified a multitude of tear-shaped amber beads that had been hung on the original wooden statue (xoanon), and these were probably carried over into later sculpted copies.[146]

In Acts of the Apostles, Ephesian metalsmiths who felt threatened by Saint Paul's preaching of Christianity, jealously rioted in her defense, shouting "Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!"[147] Of the 121 columns of her temple, only one composite, made up of fragments, still stands as a marker of the temple's location.

As a Moon goddess

There are no records of the Greeks referring to Artemis as a Moon goddess, as their Moon goddess was Selene.[148][149][150] However, the Romans identified Artemis with Selene leading them to perceive her as a Moon goddess, even though the Greeks did not refer to her or worship her as such.[151][152][153] As the Romans began to associate Apollo more with Helios, the god of the Sun, it was only natural that the Romans would then begin to identify Apollo's twin sister, Artemis, with Helios' own sister, Selene, the goddess of the Moon.[3] Evidence of the syncretism of Artemis and Selene is found early on; a scholium on the Iliad, claiming to be reporting sixth century BCE author Theagenes's interpretation of the theomachy in Book 21, says that in the fight between Artemis and Hera, Artemis represents the Moon against the earthly air (Hera).[96][154]

Active references to Artemis as an illuminating goddess start much later.[155] Notably, Roman-era author Plutarch writes how during the Battle of Salamis, Artemis led the Athenians to victory by shining with the full moon; but all lunar-related narratives of this event come from Roman times, and none of the contemporary writers (such as Herodotus) make any mention of the night or the Moon.[155]

Artemis' connection to childbed and women's labour naturally led to her becoming associated with the menstrual cycle in course of time, and thus, the Moon.[156] Selene, just like Artemis, was linked to childbirth, as it was believed that women had the easiest labours during the full moon, paving thus the way for the two goddesses to be seen as the same.[157][154] On that, Cicero writes:

Apollo, a Greek name, is called Sol, the sun; and Diana, Luna, the moon. [...] Luna, the moon, is so called a lucendo (from shining); she bears the name also of Lucina: and as in Greece the women in labor invoke Diana Lucifera,[158]

Association to health was another reason Artemis and Selene were syncretized; Strabo wrote that Apollo and Artemis were connected to the Sun and the Moon respectively was due to the changes the two celestial bodies caused in the temperature of the air, as the twins were gods of pestilential diseases and sudden deaths.[159]

Roman authors applied Artemis/Diana's byname, Phoebe, to Luna/Selene, the same way as "Phoebus" was given to Helios due to his identification with Apollo.[160] Another epithet of Artemis that Selene appropriated is "Cynthia", meaning "born in Mount Cynthus."[161] The goddesses Artemis, Selene, and Hecate formed a triad, identified as the same goddess with three avatars: Selene in the sky (moon), Artemis on earth (hunting), and Hecate beneath the earth (Underworld).[162] In Italy, those three goddesses became a ubiquitous feature in depictions of sacred groves, where Hecate/Trivia marked intersections and crossroads along with other liminal deities.[163] The Romans enthusiastically celebrated the multiple identities of Diana as Hecate, Luna, and Trivia.[163]

The Roman poet Horace in his odes enjoins Apollo to listen to the prayers of the boys, as he asks Luna, the "two-horned queen of the stars", to listen to those of the girls in place of Diana, due to their role as protectors of the young.[164] In Virgil's Aeneid, when Nisus addresses Luna/the Moon, he calls her "daughter of Latona."[165]

In works of art, the two goddesses were mostly distinguished; Selene is usually depicted as being shorter than Artemis, with a rounder face, and wearing a long robe instead of a short hunting chiton, with a billowing cloak forming an arc above her head.[166] Artemis was sometimes depicted with a lunate crown.[167]

Bow and arrow

According to one of the Homeric Hymns to Artemis, she had a golden bow and arrows, as her epithet was Khryselakatos ("she of the golden shaft") and Iokheira ("showered by arrows").[168] The arrows of Artemis could also bring sudden death and disease to girls and women. Artemis got her bow and arrow for the first time from the Cyclopes, as the one she asked from her father.[169] The bow of Artemis also became the witness of Callisto's oath of her virginity.[170]

Chariots

Artemis' chariot was made of gold and was pulled by four golden horned deer.[171] The bridles of her chariot were also made of gold.[169]

Spears, nets, and lyre

Although quite seldom, Artemis is sometimes portrayed with a hunting spear. Her cult in Aetolia, the Artemis Aetolian, showed her with a hunting spear. The description of Artemis' spear can be found in Ovid's Metamorphoses,[172] while Artemis with a fishing spear connected with her cult as a patron goddess of fishing.[173] As a goddess of maiden dances and songs, Artemis is often portrayed with a lyre in ancient art.[174]

Deer

Deer were the only animals held sacred to Artemis herself. On seeing a deer larger than a bull with horns shining, she fell in love with these creatures and held them sacred. Deer were also the first animals she captured. She caught five golden-horned deer and harnessed them to her chariot.[175] The third labour of Heracles, commanded by Eurystheus, consisted of catching the Cerynitian Hind alive. Heracles begged Artemis for forgiveness and promised to return it alive. Artemis forgave him but targeted Eurystheus for her wrath.[176]

Hunting dog

Artemis got her hunting dogs from Pan in the forest of Arcadia. Pan gave Artemis two black-and-white dogs, three reddish ones, and one spotted one – these dogs were able to hunt even lions. Pan also gave Artemis seven bitches of the finest Arcadian race. However, Artemis only ever brought seven dogs hunting with her at any one time.[177]

Bear

The sacrifice of a bear for Artemis started with the Brauron cult. Every year a girl between five and ten years of age was sent to Artemis' temple at Brauron. The Byzantine writer Suidos relayed the legend in Arktos e Brauroniois. A bear was tamed by Artemis and introduced to the people of Athens. They touched it and played with it until one day a group of girls poked the bear until it attacked them. A brother of one of the girls killed the bear, so Artemis sent a plague in revenge. The Athenians consulted an oracle to understand how to end the plague. The oracle suggested that, in payment for the bear's blood, no Athenian virgin should be allowed to marry until she had served Artemis in her temple ('played the bear for the goddess').[178]

Boar

The boar is one of the favorite animals of the hunters, and also hard to tame. In honor of Artemis' skill, they sacrificed it to her. Oeneus[179] and Adonis[180] were both killed by Artemis' boar.

Guinea fowl

Artemis felt pity for the Meleagrids as they mourned for their lost brother, Meleager, so she transformed them into Guinea Fowl to be her favorite animals.[181]

Buzzard hawk

Hawks were the favored birds of many of the gods, Artemis included.[182]

In art

The oldest representations of Artemis in Greek Archaic art portray her as Potnia Theron ("Queen of the Beasts"): a winged goddess holding a stag and lioness in her hands, or sometimes a lioness and a lion. This winged Artemis lingered in ex-votos as Artemis Orthia, with a sanctuary close by Sparta.

In Greek classical art she is usually portrayed as a maiden huntress, young, tall, and slim, clothed in a girl's short skirt,[183] with hunting boots, a quiver, a golden or silver bow[184] and arrows. Often, she is shown in the shooting pose, and is accompanied by a hunting dog or stag. When portrayed as a Moon goddess, Artemis wore a long robe and sometimes a veil covered her head. Her darker side is revealed in some vase paintings, where she is shown as the death-bringing goddess whose arrows fell young maidens and women, such as the daughters of Niobe.

Artemis was sometimes represented in Classical art with the crown of the crescent moon, such as also found on Luna and others.

On June 7, 2007, a Roman-era bronze sculpture of Artemis and the Stag was sold at Sotheby's auction house in New York state by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery for $25.5 million.

Legacy

In astronomy

105 Artemis, the Artemis (crater), the Artemis Chasma, the Artemis Corona, and the Artemis program have all been named after the goddess.

Artemis is the acronym for "Architectures de bolometres pour des Telescopes a grand champ de vue dans le domaine sub-Millimetrique au Sol", a large bolometer camera in the submillimeter range that was installed in 2010 at the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX), located in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile.[185]

In taxonomy

The taxonomic genus Artemia, which entirely comprises the family Artemiidae, derives from Artemis. Artemia are aquatic crustaceans known as brine shrimp, the best-known species of which, Artemia salina, or Sea Monkeys, was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae in 1758. Artemia live in salt lakes, and although they are almost never found in an open sea, they do appear along the Aegean coast near Ephesus, where the Temple of Artemis once stood.

In modern spaceflight

The Artemis program is an ongoing crewed spaceflight program carried out by NASA, U.S. commercial spaceflight companies, and international partners such as ESA,[186] with the goal of landing "the first woman and the next man" on the lunar south pole region by 2024. NASA is calling this the Artemis program in honor of Apollo's twin sister in Greek mythology, the goddess of the Moon.[187]

Genealogy

| Artemis' family tree [188] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Bendis

- Dali (goddess)

- Janus

- Lunar deity

- Palermo Fragment

- Regarding Tauropolos:

- Bull (mythology)

- Iphigenia in Tauris

- Taurus (Mythology)

References

- "Artemis | Myths, Symbols, & Meaning". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Inc, Merriam-Webster (1995). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster. p. 74. ISBN 9780877790426.

- Smith, s.v. Artemis

- Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (5), 21–32

- Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 9781438126395.

- "Artemis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (2005). "Άρτεμις". Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας. Athens: Κέντρο Λεξικολογίας. p. 286.

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 142.

- Indogermanica et Caucasica: Festschrift fur Karl Horst Schmidt zum 65. Geburtstag (Studies in Indo-European language and culture), W. de Gruyter, 1994, Etyma Graeca, pp. 213–214, on Google books; Houwink ten Cate, The Luwian Population Groups of Lycia and Cilicia Aspera during the Hellenistic Period (Leiden) 1961:166, noted in this context by Brown 2004:252.

- Michaël Ripinsky-Naxon, The Nature of Shamanism: Substance and Function of a Religious Metaphor (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993), 32.

- Campanile, Ann. Scuola Pisa 28:305; Restelli, Aevum 37:307, 312.

- Edwin L. Brown, "In Search of Anatolian Apollo", Charis: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr, Hesperia Supplements 33 (2004:243–257). p. 251: Artemis, as Apollo's inseparable twin, is discussed in pp. 251ff.

- John Chadwick and Lydia Baumbach, "The Mycenaean Greek Vocabulary" Glotta, 41.3/4 (1963:157-271). p. 176f, s.v. Ἂρτεμις, a-te-mi-to- (genitive); C. Souvinous, "A-TE-MI-TO and A-TI-MI-TE", Kadmos 9 1970:42–47; T. Christidis, "Further remarks on A-TE-MI-TO and A-TI-MI-TE", Kadmos 11:125–28.

- Anthon, Charles (1855). "Artemis". A Classical dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 210.

- Lang, Andrew (1887). Myth, Ritual, and Religion. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 209–210.

- ἄρταμος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Ἄρτεμις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ἀρτεμής. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Van Windekens 1986: pp. 19‒20.

- Blažek, Václav. "Artemis and her family". In: Graeco-Latina Brunensia vol. 21, iss. 2 (2016). p. 40. ISSN 2336-4424

- Powell 2012, p. 225.

- Powell 2012, p. 56.

- Immendörfer 2017, p. 225.

- Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White.

- Konstan 2014, p. 65.

- Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods Hera and Leto

- Homer, Odyssey 6.102 ff

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.138 ff

- Pausanias 1.29.2 (Athens), 8.35.8 (Tegea)

- Keightley 1838, p. 135.

- Shelmerdine 1995, p. 63.

- Rutherford 2001, p. 368.

- Homer, Iliad 1.9 and 21.502–510; Hesiod, Theogony 918–920

- Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 14–18; Gantz, p. 38; cf. Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto, 3–5 (Athanassakis & Wolkow, p. 31).

- Hammond. Oxford Classical Dictionary. 597-598.

- Or as a separate island birthplace of Artemis: "Rejoice, blessed Leto, for you bear glorious children, the lord Apollon and Artemis who delights in arrows; her in Ortygia, and him in rocky Delos," says the Homeric Hymn; the etymology Ortygia, "Isle of Quail", is not supported by modern scholars.

- McLeish, Kenneth. Children of the Gods pp 33f; Leto's birth-pangs, however, are graphically depicted by ancient sources.

- Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 3.73

- Rutherford 2001, pp. 364–365.

- Callimachus, Hymn III to Artemis 1-27.

- Mair, pp. 62–63 note a.

- Callimachus, Hymn III to Artemis 46 ff..

- Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.84.1

- Homer, Iliad 5.50

- "I think that this is an aetiological myth, intended to explain the rite in which a human effigy was burnt upon a pyre in the festival of the hunters' goddess," observes Martin P. Nilsson, "Fire-Festivals in Ancient Greece", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 43.2 (1923:144-148) p. 144 note 2; Pseudo-Apollodorus, Epitome 2.2

- Forbes Irving, pp. 89, 149 n. 1, 166; Fontenrose, p. 125; Antoninus Liberalis, 17 (Celoria, p. 71; Papathomopoulos, p. 31).

- Heath, "The Failure of Orpheus", Transactions of the American Philological Association 124 (1994:163-196) p. 196.

- Walter Burkert, Homo Necans (1972), translated by Peter Bing (University of California Press) 1983, p 111.

- Lacy, "Aktaion and a Lost 'Bath of Artemis'" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 110 (1990:26-42)

- Apollodorus, 3.4.4

- Aeschylus fr 135 (244), Aeschylus: Agamemnon, Libation-Bearers, Eumenides, Fragments. Translated by Smyth, Herbert Weir. Loeb Classical Library Volume 146. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1926, p. 464.

- Mattheson, p. 264

- Euripides, Bacchae 330-342

- Callimachus, Hymn 5 On the Bath of Pallas 109-115

- Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.81.3-5

- Hyginus, Fabulae 181

- Chisholm 1911.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.138 ff.; Grimal, s.v. Actaeon, p. 10

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 9.2.3

- Homer, Iliad 24.602 ff, trans. Lattimore.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.146 ff

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.146 ff

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.21.9

- Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 32 [= Hesiod, Astronomia fr. 4 Evelyn-White, pp. 70–73 = fr. 7 Freeman, pp. 12–13; Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.26.2; Hard, p. 564; cf. Hyginus, Fabulae 195.

- Ovid, Fasti 5.539.

- Kerenyi 1951 (p. 204) says that this is "[a]nother name for Artemis herself".

- Apollodorus 1.4.5.

- Aratus, Phaenomena 638.

- Callimachus, Hymn III to Artemis 265; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 48.395.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.34.4.

- Homer, Iliad 5.121–124; Gantz, p. 97; Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Orion; Hansen, p. 118.

- Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 1 [= Hesiod, Astronomia fr. 3 Evelyn-White, pp. 68–71 = fr. 6 Freeman, p. 12; Gantz, p. 725; Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Callisto; Pausanias, 1.25.1, 8.2.6; Hyginus, Fabulae 176, 177. According to the Bibliotheca, Eumelos "and some others" called Callisto the daughter of Lycaon, Asius called her the daughter of Nycteus, Pherecydes called her the daughter of Ceteus, and Hesiod called her a nymph. (Apollodorus, 3.8.2 [= Eumelos, fr. 32 (West 2003, pp. 248–249) = Asius fr. 9 (West 2003, pp. 258–259) = Pherecydes FGrHist 3 F86 = Hesiod, fr. 163 Merkelbach-West]).

- Apollodorus, 3.8.2; Gantz, p. 98; Tripp, s.v. Callisto, pp. 145–146; cf. Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 1 [= Hesiod, Astronomia fr. 4 Evelyn-White, pp. 70–73 = fr. 7 Freeman, pp. 12–13.

- Gantz (p. 275) notes that "[t]he text here seems to indicate that Arkas (and others) pursued [Callisto] only after she had entered the sanctuary, and only because she had done so".

- Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 1 [= Hesiod, Astronomia fr. 3 Evelyn-White, pp. 68–71 = fr. 6 Freeman, p. 12; Gantz, p. 98, 725–726; cf. Hesiod, Astronomia fr. 3 Evelyn-White, pp. 68–71.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.1.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.2.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.3; Gantz, p. 727. Compare with Hyginus, Fabulae 177 and Pausanias, 8.2.6.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.4; Gantz, p. 727; cf. Apollodorus, 3.8.2.

- Gantz (p. 726) says that "Kallisto realizes the identity (or at least the gender) of her seducer...".

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 401–530; Gantz, p. 726.

- In the first version, Artemis was not aware the bear was Callisto. (Gantz, p. 727) Of the second version, Gantz (p. 727) says that it "[q]uite probably … implies a variant in which Kallisto does not become a bear at all, as Artemis is not likely to transform her and shoot her, or to slay her for her own reasons after Hera has accomplished the transformation".

- Apollodorus, 3.8.2; Gantz, p. 727; Tripp, s.v. Callisto, pp. 145–146; cf. Eumelos, fr. 32 (West 2003, pp. 248–249) [= Apollodorus, 3.8.2. Gantz (p. 727) suggests that this version may have come from Pherecydes, while West 2003 says that Eumelos "must have told the story of how Zeus made love to Callisto and changed her into a bear. Artemis killed her, but Zeus saved her child, who was Arcas." (West 2003, p. 249, note 26 to fr. 32).

- Pausanias, 8.2.6; Gantz, p. 727. Compare with Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.3 and Pausanias, 1.25.1.

- Pausanias, 8.2.6–7; Gantz, p. 727; cf. Apollodorus, 3.8.2.

- Homer, Odyssey 11.580 ff; Pindar, Pythian Odes 4.161–165; Apollodorus 1.4.1; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 3.390 ff; Hard, pp 147–148

- Hyginus, Fabulae 200; Hard, p. 192.

- Grimal, s.v. Aura, p. 71.

- Apollodorus, 3.14.4; cf. Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.652; Hyginus, Fabulae 248; Plutarch, Quaestiones Convivales 4.5.3; Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 2.80.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 42.204–211; Grimal, s.v. Adonis, pp. 12–13.

- Antoninus Liberalis, 21.

- Pindar, Pythian Ode 3 str1-ant3; Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.26.6

- Hyginus, Astronomica 2.16.2

- Atsma, Aaron J. "FAVOUR OF ARTEMIS: Greek mythology". Theoi.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Atsma, Aaron J. "FAVOUR OF ARTEMIS: Greek mythology". Theoi.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Scholia on the Iliad 20.67 ; Hansen, p. 10; Anecdota græca e codd. manuscriptis Bibliothecæ regiæ parisiensis, p. 120

- Homer, Iliad 21.468-497

- Homer, Iliad 502-510

- “. . . a goddess universally worshipped in historical Greece, but in all likelihood pre-Hellenic.” Hammond, Oxford Classical Dictionary, 126.

- Golden, M., Children and Childhood in Classical Athens (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), p. 84.

- Wise, Susan (2007). Childbirth Votives and Rituals in Ancient Greece (PhD). University of Cincinnati.

- van der Toorn et al, s.v. Artemis, p. 93

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome' s.v. Artemis, p. 268

- The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, p. 81

- Budin, p. 110 "One site especially famous for its choruses dedicated to Artemis was Ephesos. According to the Hellenistic poet Kallimakhos, this custom was established by the Amazons who founded the cult by dancing around a wooden image of the goddess."

- "SOL Search". www.cs.uky.edu.

- Pausanias, iii. 14. § 2.

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Aeginaea". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston. p. 26. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- Bremmer, Jan N. (14 December 2008). Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible, and the Ancient Near East. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004164734 – via Google Books.

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Lygodesma". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 2. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., pp. 860–861.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.29.2

- Leake, William Martin (1830). "Travels in the Morea: with a map and plans". Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "CALLIMACHUS, HYMNS 1-3 - Theoi Classical Texts Library". Retrieved 16 January 2020. (3, verse 170)

- "Plutarch • Life of Agesilaus". Retrieved 16 January 2020. (32,4)

- Pausanias, x. 38. § 6.

- "Among the Heneti certain honours have been decreed to Diomedes; and, indeed, a white horse is still sacrificed to him, and two precincts are still to be seen — one of them sacred to the Argive Hera and the other to the Aetolian Artemis. (Strabo, v.1.9 on-line text).

- Smith, s.v. Daphnaea

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Alphaea". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 133. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece vi. 22. § 5

- Strabo, Geographica viii. p. 343

- Scholiast on Pindar's Pythian Odes ii. 12, Nemean Odes i. 3

- Dickins, G.; Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (1929). "Terracotta Masks". The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia: Supplementary Papers. London, England: Macmillan Publishers. p. 172. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- Smith, s.v. Hemeresia

- "Strabo, Geography, Book 12, chapter 2, section 7". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "Pausanias, Description of Greece, *lakwnika/, chapter 25, section 3". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "Pausanias, Description of Greece, *)arkadika/, chapter 14, section 5". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnika, Ch694.8

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Chitonia

- "ARTEMIS TITLES & EPITHETS - Ancient Greek Religion". www.theoi.com.

- "Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, book 14, chapter 27". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "THE SANCTUARY OF ARTEMIS CHITONE AND THE EARLY CLASSICAL SETTLEMENT ON THE EASTERN TERRACE OF THE KALABAKTEPE IN MILETUS - Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut".

- "Appian, The Civil Wars, BOOK V, CHAPTER I". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "Pausanias, Description of Greece, *)attika/, chapter 26, section 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Leucophryne". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Mikalson, p. 18

- mharrsch (4 November 2007). "Passionate about History: Search continues for temple of Artemis Amarysia". Passionateabouthistory.blogspot.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "SARON, Greek Mythology Index". Mythindex.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Ancient Athenian Festival Calendar". Winterscapes.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Ancient Athenian Festival Calendar". Winterscapes.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Ancient Athenian Festival Calendar". Winterscapes.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Ancient Athenian Festival Calendar". Winterscapes.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Ancient Athenian Festival Calendar". Winterscapes.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Hjerrild, B. (2009). Near Eastern equivalents to Artemis. Tobias Fischer-Hansen & Birte Poulsen, eds. From Artemis to Diana: The Goddess of Man and Beast. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 8763507889, 9788763507882.

- The Homeric hymns. Translated by Cashford, Jules. London: Penguin Books. 2003. ISBN 0-14-043782-7. OCLC 59339816.

- ""Potnia Aswia: Anatolian Contributions to Greek Religion" by Sarah P. Morris". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- Acts 19:28.

- Sacks (1995), p. 35

- Hard, p. 46; Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Selene; Morford, pp. 64, 219–220; Smith, s.v. Selene.