Hasan ibn Ali

Hasan ibn Ali (Arabic: حسن ابن علي, romanized: Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī; c. 625 – 2 April 670[lower-alpha 1]) was a prominent early Islamic figure. He was the eldest son of Ali and Fatima and a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He briefly ruled as caliph from January 661 until August 661. He is considered as the second Imam in Shia Islam, succeeding Ali and preceding his brother Husayn. As a grandson of the prophet, he is part of the ahl al-bayt and the ahl al-kisa, also he is claimed to have participated in the event of Mubahala.

| Hasan ibn Ali حسن ابن علي | |

|---|---|

| |

Hasan's name in Arabic calligraphy | |

| 5th Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate (under Ali's era) | |

| Reign | January 661 – August 661 |

| Predecessor | Ali ibn Abi Talib |

| Successor | Abolished position Mu'awiya I (as Umayyad caliph) |

| 2nd Shia Imam | |

| Tenure | 661–670 |

| Predecessor | Ali ibn Abi Talib |

| Successor | Husayn ibn Ali |

| Born | c. 625 Medina, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Died | 2 April 670 (aged 44) Medina, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Burial | Al-Baqi Cemetery, Medina |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue |

|

| Tribe | Quraysh (Banu Hashim) |

| Father | Ali ibn Abi Talib |

| Mother | Fatima bint Muhammad |

| Religion | Islam |

| Part of a series on |

| Hasan ibn Ali |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

During the caliphate of Ali (r. 656–661), Hasan accompanied him in the military campaigns of the First Muslim Civil War. After Ali's assassination in 661, Hasan was subsequently acknowledged caliph in Kufa. His sovereignty was unrecognized by Syria's governor Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), who led an army into Kufa to press the former for abdication. In response, Hasan sent a vanguard under Ubayd Allah ibn al-Abbas to block Mu'awiya's advance until he arrived with the main army. Meanwhile, Hasan was severely wounded in an abortive assassination attempt made by the Kharijites, a faction opposed to both Ali and Mu'awiya. This attack demoralized Hasan's army, and many deserted. On the other hand, Ubayd Allah and most of his troops defected after Mu'awiya bribed him. In August 661 Hasan signed a peace treaty with Mu'awiya on the basis that the latter should rule in compliance with the Quran and the sunna, a council appointed his successor, and his supporters received amnesty. Hasan retired from politics and abdicated in Medina where he eventually died either by a long-term illness or poisoning at the instigation of Mu'awiya, who wanted to install his son Yazid (r. 680–683), as his successor.[2][3]

Critics of Hasan call his treaty with Mu'awiya an indication of weakness, saying that he had intended to surrender from the beginning and fought half-heartedly. His supporters maintain that Hasan's abdication was inevitable after his soldiers mutinied, and he was motivated by the desire for unity and peace in the Muslim community; Muhammad reportedly predicted in a hadith that Hasan would make peace among the Muslims. Another Sunni hadith (also attributed to Muhammad) predicted that the prophetic succession would endure for thirty years, which may have been interpreted by at least some early Sunni scholars as evidence that Hasan's caliphate was rightly-guided (rāshid).[4] In Shia theology, the divine infallibility (isma) of Hasan as the second Shia Imam justified his course of action. Shiites do not consider Hasan's resignation from political power detrimental to his imamate, which is based on Nass (divine designation by Muhammad and Ali). In Shia theology, the imamate is not transmissible to another person by allegiance or voluntary resignation.

Early life

Hasan was born in Medina in c. 625. Sources differ on whether he was born in the month of Ramadan or of Shaban.[5] According to most traditional sources, Hasan was born on the 15th of Ramadan 3 AH (2 March 625 CE).[6] He was the firstborn of Ali (Muhammad's cousin) and Fatima, Muhammad's daughter.[7] Ali reportedly had chosen another name, but Muhammad chose the name Hasan for him.[lower-alpha 2][8][6] To celebrate his birth, Muhammad sacrificed a ram; Fatima shaved Hasan's head and donated the weight of his hair in silver.[6]

Muhammad was reportedly very fond of Hasan and his brother Husayn, carrying the boys on his shoulders, laying them on his chest and kissing them.[6] Of the two boys, Hasan is said to have resembled his grandfather more in appearance.[6] According to Wilferd Madelung, Muhammad's statement that Hasan and Husayn would be the lords of youth in Paradise was widely reported.[6] Hasan was raised in his grandfather's household until age seven, when Muhammad died.[6] Hasan later recalled the prayers Muhammad had taught him, as well as other sayings and deeds of Muhammad, including the time he took a date from Hasan's lips and told him that receiving alms (Sadaqah) was not licit for any member of his family.[6][9]

In October 631 (10 AH), Hasan reportedly participated in the event of Mubahala, a meeting between the Najranite Christians and Muhammad.[lower-alpha 3][14] The event occurred when Muhammad is said to have taken Ali, Fatima, Hasan and his brother, Husayn, under his cloak, addressed them as his ahl al-bayt (People of the House), and declared them free from sin and impurity.[lower-alpha 4][1][19] While all Muslims revere the ahl al-Bayt,[20][21] it is the Shia who hold the ahl al-Bayt in the highest esteem, regarding them as infallible embodiments of divine wisdom and the perfect leaders for the Muslim community.[22][20]

Rashidun Caliphate

Caliphate of Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman

Hasan remained politically inactive during the caliphate of Abu Bakr (r. 632–634).[23] During Umar's caliphate (r. 634–644), Hasan received 5,000 dirhams as a pension from the state revenue.[24] In accounts preserved by Ibn Isfandiyar, Hasan reportedly took part in an expedition of Amol in Tabaristan along with Abd Allah ibn Umar.[6] During the third caliph Uthman's reign (r. 644–656), Hasan participated in the conquest of Tabaristan under Sa'id ibn al-As.[25] Hasan joined his father (defying Uthman) in bidding farewell to Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, who was exiled from Medina after he preached against the misdeeds of the powerful.[26] After Uthman's half-brother, al-Walid ibn Uqba, was accused of drinking alcohol, Ali asked Hasan to carry out the punishment of forty lashes, though Hasan is said to have refused his father's suggestion. Ali is said to have rebuked Hasan, and asked his nephew Abdullah ibn Ja'far to administer the punishment.[6] Laura Veccia Vaglieri writes that some accounts report that Ali instead meted out the punishment.[26] According to Vaglieri, Hasan and Husayn had no role in the important events of the caliphate of Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman. Both Hasan and Husayn were obedient to Ali; they followed their father when he opposed Uthman.[lower-alpha 5][1]

In June 656, Uthman was besieged in his home by rebels. Hasan and Husayn were reportedly wounded, while guarding Uthman's house at Ali's request.[28][29][30] Hasan laid down his weapons on the final day at Uthman's request.[6] Another report says that after Uthman was assassinated, Hasan arrived at the scene of the murder in time to identify his assassins.[1] According to Madelung, Hasan criticized Ali for not doing enough to defend Uthman.[6]

Caliphate of Ali

Ali was elected caliph after the assassination of Uthman. Immediately after his accession, the new caliph faced a rebellion led by Aisha, a widow of Muhammad, and Talha and Zubayr, both companions of Muhammad.[31] Hasan was subsequently sent to Kufa to rally support with Ammar ibn Yasir and raised an army of 6,000 to 7,000 men.[1][6] He also helped remove Abu Musa al-Ash'ari from the rule of Kufa,[32] as the latter continued to hinder Ali's efforts against the rebels.[32][28][33] Hasan later fought in the Battle of the Camel (656) against Aisha, Talha, and Zubayr.[6]

Hasan also fought against Mu'awiya (r. 661–680) in the Battle of Siffin (657), though (Sunni) sources do not name him as a prominent participant.[6][34] Madelung also holds that Hasan criticized Ali's alleged aggressive war policy, saying that it stoked division among Muslims.[6] Alternatively, the Sunni Ibn 'Abd al-Barr (d. 1071) lists Hasan as a commander at Siffin and the narrations quoted by the Shia Nasr ibn Muzahim (d. 827-8) indicate that Mu'awiya might have made unsuccessful offers to Hasan to switch sides at Siffin.[35] Haj-Manouchehri believes that Hasan persuaded some neutral figures to support Ali at Siffin, including Sulayman ibn Surad al-Khuza'i, and writes about Hasan's vocal opposition to the arbitration process after Siffin, alongside his father.[35]

In November 658, Ali made Hasan responsible for his land endowments.[6]

Caliphate

In January 661, Ali was assassinated by Abd al-Rahman ibn Muljam, a Kharijite rebel.[36] Hasan was subsequently acknowledged caliph in Kufa, the seat of Ali's caliphate.[37][1] Some authors have noted that Muhammad's companions were primarily in Ali's army and must have therefore pledged allegiance to Hasan, as evidenced by the lack of any reports to the contrary.[38][39] In his inaugural speech at the Great Mosque of Kufa, Hasan praised the ahl al-bayt and quoted verse 42:23 of the Quran:

I am of the Family of the Prophet from whom God has removed filth and whom He has purified, whose love He has made obligatory in His Book when He said, "Whosoever performs a good act, We shall increase the good in it." Performing a good act is love for us, the Family of the Prophet.[40]

Ali's commander Qays ibn Sa'd is recorded to have been the first to pledge his allegiance to Hasan. Qays suggested that the oath should be based on the Quran, precedent (sunna), and jihad against those who declared lawful (halal) what was unlawful (haram). Hasan, however, avoided the last condition by saying that it was implicit in the first two.[41][1] Jafri (d. 2019) writes that Hasan was probably already apprehensive about the trustworthiness of the Kufans and wanted to avoid unrealistic commitments.[41] The oath stipulated that people "should make war on those who were at war with Hasan, and should live in peace with those who were at peace with him," writes the Sunni al-Baladhuri (d. 892), adding that this condition astonished the people, who suspected that Hasan intended to make peace with Mu'awiya.[1][42] Madelung, however, notes that the oath was identical to the one demanded earlier by Ali and denounced by the Kharijites.[43] The view of Dakake is similar.[42]

Conflict with Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya, who had been at war with Ali, did not recognize the caliphate of Hasan and prepared for war. He marched an army of sixty thousand men through al-Jazira to Maskin, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of present-day Baghdad. Concurrently, Mu'awiya also negotiated with Hasan by letter, urging him to give up his claim to the caliphate.[44][1] Jafri writes that he might have hoped to force Hasan to abdicate or attack the Iraqi forces before they were fortified. Mu'awiya might have believed that Hasan would remain a threat even if he was defeated and killed, since another Hashemite could continue the fight. If Hasan abdicated in favor of Mu'awiya, he writes, such claims would have no weight.[45] The view of Momen is similar.[46]

Their letters revisit the succession of Muhammad. Hasan urged Mu'awiya to pledge allegiance to him by invoking the same arguments advanced by Ali against Abu Bakr after the death of Muhammad. Ali said that if the Quraysh could successfully claim the leadership because Muhammad belonged to them, then Muhammad's family were the most qualified to lead.[47] Mu'awiya replied that the Muslim community was not unaware of the merits of the ahl al-bayt but had selected Abu Bakr to keep the caliphate within the Quraysh.[48] Hassan also wrote that Mu'awiya had no true merit in Islam and was the son of Muhammad's arch-enemy Abu Sufyan.[47][46] Mu'awiya replied that he was better suited for the caliphate because of his age, military strength, and governing experience,[48][46] thus implying that these qualities were more important than religious precedence.[46] Jafri comments that Mu'awiya's response made explicit the separation of politics and religion, which became a tenet of Sunni Islam. In contrast, Shia Islam vested all authority in the household of Muhammad.[49]

Mobilization of troops and mutiny

As the news of Mu'awiya's advancing army reached Hasan, he ordered his local governors to mobilize and addressed the people of Kufa: "God had prescribed the jihad for his creation and called it a loathsome duty (kurh)," referring to verse 2:216 of the Quran.[44] There was no response at first,[1] possibly because some tribal chiefs were bribed by Mu'awiya and were reluctant to move.[50] Hasan's companions scolded the crowd and inspired them to leave in large numbers for the army campgrounds in Nukhayla.[50] Hasan soon joined them and appointed Ubayd Allah ibn Abbas as the commander of a vanguard of twelve thousand men tasked with holding Mu'awiya back in Maskin until the arrival of Hasan's main army. He was advised not to fight unless attacked and to consult with Qays ibn Sa'd, the second in command.[50][51][1][52] Wellhausen (d. 1918) names Abd Allah ibn Abbas as the commander of the vanguard[53] but this is rejected by Madelung,[50] who suggests that the choice of Ubayd Allah ibn al-Abbas indicates Hasan's hope of reaching a peaceful conclusion because the former had earlier surrendered Yemen to Mu'awiya without a fight.[6]

While the vanguard was awaiting his arrival at Maskin, Hasan faced a mutiny at his military camp near al-Mada'in. Jafri writes that there are five accounts of this incident. The account by Abu Hanifa Dinawari (d. 895) states that Hasan was concerned about his troops' resolve by the time he reached the outskirts of al-Mada'in. He thus halted the army at Sabat and told them in a speech that he preferred peace over war because his men were reluctant to fight.[54][55][50]

Taking this as a sign that he intended to pursue peace, Kharijite sympathizers in Hasan's army looted his tent and pulled his prayer rug from under him.[55][42][1] As he was being escorting away to safety, the Kharijite al-Jarrah ibn Sinan attacked and wounded Hasan, while shouting, "You have become an infidel (kafir) like your father."[1][55][56] Al-Jarrah was overpowered and killed,[56] while Hasan, bleeding profusely,[1] was taken for treatment to the house of Sa'd ibn Mas'ud al-Thaqafi, the governor of al-Mada'in.[55][56] The news of this attack further demoralized Hasan's army and led to widespread desertion.[57][1][58] Sa'd's nephew Mukhtar ibn Abi Ubayd (d. 687) reportedly recommended the governor to surrender Hasan to Mu'awiya but was rejected.[59]

Vanguard at Maskin

The Kufan vanguard arrived in Maskin and found Mu'awiya camped there. Through a representative, he urged them not to commence hostilities until he concluded his peace talks with Hasan. This was a false claim, suspects Madelung, but Mu'awiya probably thought that he could indeed force Hasan to surrender.[60][61] The Kufans, however, insulted Mu'awiya's envoy and sent him back. Mu'awiya then sent the envoy to visit Ubayd Allah privately, telling him that Hasan had requested a truce and offering Ubayd Allah a million dirhams to switch sides. Ubayd Allah accepted and deserted at night to Mu'awiya, who fulfilled his promise to him.[62][60][63]

The next morning, second-in-command Qays ibn Sa'd took charge of Hasan's troops and denounced Ubayd Allah in a sermon. Believing that Ubayd Allah's desertion had broken his enemy's spirit, Mu'awiya sent a contingent to force surrender but was pushed back twice.[64] He then offered bribes to Qays in a letter, which he refused.[64][63] As the news of the mutiny against Hasan and the attempt at his life arrived, however, both sides abstained from fighting and awaited further developments.[65] Veccia Vaglieri writes that the Iraqis had no wish to fight, and a group deserted every day.[1] By one account, 8,000 men out of 12,000 followed Ubayd Allah's example and joined Mu'awiya.[63][1]

Treaty with Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya now sent envoys to propose that Hasan abdicate in his favor to spare Muslim blood. In return, Mu'awiya was ready to designate Hasan as his successor, grant him safety, and offer him a large financial settlement.[65][46] Hasan now sent his representative(s) to Mu'awiya and the latter gave Hasan carte blanche, inviting him to dictate what he wanted. Hasan wrote that he would surrender Muslim rule to Mu'awiya if he would comply with the Quran and sunna, his successor would be appointed by a council (shura), the people would remain safe, and Hasan's supporters would receive amnesty.[6][66] His letter was witnessed by two representatives, who gave it to Mu'awiya.[67] He thus renounced the caliphate in August 661 after a seven-month reign.[6][68][69]

Terms of the treaty

Veccia Vaglieri finds certain variants of the treaty impossible to reconcile. She lists several conditions and questions their veracity, including an annual payment of one or two million dinars to Hasan, a single payment of five million dinars from the treasury of Kufa, annual revenues from variously-named districts in Persia, succession of Hasan to Mu'awiya or a council (shura) after Mu'awiya, and preference given to the Banu Hashim over the Banu Umayyad in pensions.[1]

Jafri similarly notes that al-Tabari (d. 923), Dinawari, Ibn Abd al-Barr, and Ibn al-Athir record the terms differently and ambiguously, while al-Ya'qubi (d. 897-8) and al-Masudi (d. 956) are silent about them. In particular, Jafri finds the timing of the Mu'awiya's carte blanche confusing in al-Tabari's account.[70] Al-Tabari also mentions a single payment of five million dinnars to Hasan from the treasury of Kufa,[71][1] though Jafri rejects this, saying that the treasury of Kufa was already in Hasan's possession at that point and that Ali regularly emptied the treasury and distributed the funds among the public.[71]

Jafri then argues that the most comprehensive account is the one given by Ahmad ibn A'tham, probably taken from al-Mada'ini (d. 843), who recorded the terms in two parts. The first part are the conditions proposed by Abd Allah ibn Nawfal, who negotiated on Hasan's behalf with Mu'awiya in Maskin.[lower-alpha 6] The second part are what Hasan stipulated in carte blanche.[lower-alpha 7] These two sets of conditions together encompass all the conditions scattered in the early sources.[74]

Jafri thus concludes that Hasan's final conditions in carte blanche were that Mu'awiya should act according to the Quran, sunna, and the conduct of the Rashidun caliphs, that the people should remain safe, and that the successor to Mu'awiya should be appointed by a council.[6] These conditions are echoed by Madelung.[66] Since Ali and his house rejected the conduct of Abu Bakr and Umar in the shura after the Umar, Jafri suggests that the clause about following the Rashidun caliphs was inserted by later Sunni authors.[75] That Mu'awiya agreed to an amnesty for the supporters of Ali indicates that the revenge for Uthman was a pretext for him to seize the caliphate, according to Jafri.[69]

Abdication and retirement in Medina

During the surrender ceremony, Mu'awiya demanded Hasan to publicly apologize. Hasan rose and reminded the people that he and Husayn were Muhammad's only grandsons and the right to the caliphate was his and not Mu'awiya's, but he had surrendered it to avoid bloodshed.[6] In his speech, Mu'awiya recanted his earlier promises to Hasan and others, saying that those promises were made to shorten the war.[6] As reported by the Mu'tazilite Ibn Abi'l-Hadid (d. 1258) and Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani (d. 967), Mu'awiya added that he had not fought the Iraqis so that they would practice Islam, which they were already doing, but to be their master (amir).[76] The Sunni al-Baladhuri (d. 892) writes that Mu'awiya then gave them three days to pledge allegiance or be killed. The people thus rushed to vow allegiance to Mu'awiya.[77] Hasan left Kufa for Medina but soon received a request from Mu'awiya to subdue a Kharijite revolt near Kufa. He wrote back to Mu'awiya that he had given up his claim to the caliphate for the sake of peace and compromise, not to fight on his side.[78][79][1]

Between his abdication in 41/661 and his death in 50/670, Hasan lived quietly in Medina and did not engage in politics.[34] In compliance with the peace treaty, Hasan declined requests from (often small) Shia groups to lead them against Mu'awiya.[80][81] He was nevertheless considered the head of Muhammad's household by the Banu Hashim and Ali's partisans, who had probably pinned their hopes on his succession to Mu'awiya.[82] Al-Baladhuri in Ansab writes that Hasan sent tax collectors to the Fasa and Darabjird provinces of Iran in accordance with the treaty but the governor of Basra, instructed by Mu'awiya, incited the Basrans against Hasan and his tax collectors were driven out of the provinces. Madelung regards this account as fictitious because Hasan had just refused to join Mu'awiya in fighting the Kharijites, adding that the former had made no financial stipulations in his peace proposal.[83] He suggests that the relations between the two men deteriorated when Mu'awiya realized that Hasan would not actively support his regime.[6]

Death and burial

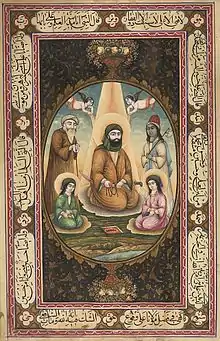

_MET_sf1979-211.jpg.webp)

According to the most credible reports, Hasan ibn Ali died on 2 April 670 (5 Rabi' al-Awwal 50 AH)[lower-alpha 8][6] from an illness or poisoning.[1] Madelung notes that early sources are nearly unanimous that Hasan was poisoned.[6] According to some sources, he was poisoned by his Kindite wife Ja'da bint al-Ash'ath whereas other accounts accuse his Amirite wife Hind bint Suhayl.[84] According to al-Waqidi (d. 823), one of Hasan's servants gave a poisoned drink to the latter.[84] In all cases, Mu'awiya is identified as the instigator.[23][2][85][3][lower-alpha 9] Mu'awiya reportedly convinced Hasan's wife to poison him with the promise of a large sum of money and marriage to his son, Yazid.[1] Al-Shaykh al-Mufid (d. 1022) said that Mu'awiya promised to pay Ja'da 100,000 dirham and marry Yazid (r. 680–683) to her.[87] The modern Belgian historian Henri Lammens, however, considered these reports "insignificant".[84] Ahmed and Madelung wrote that the claims were Alid propaganda against Ja'da, who was considered a traitor.[88] The early historian al-Tabari (d. 923) denied Mu'awiya's alleged role in Hasan's death; Donaldson and Madelung suggested that this may have been out of concern for the faith of the common people (awamm).[89][85] Some sources report that Yazid I (r. 680–683), proposed to Zaynab bint Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, who refused and instead preferred Hasan. The enraged Yazid subsequently had Hasan poisoned.[90][91] Hasan reportedly did not disclose the identity of his suspected poisoner to Husayn, fearing that the wrong person might be punished.[1] Thirty-eight years old when he abdicated to 58-year-old Mu'awiya, the age difference presented a problem for Mu'awiya (who wanted to make Yazid his heir-apparent). The move would have been unlikely because of the terms on which Hasan had abdicated. Given their age difference, Mu'awiya could not expect Hasan to die before him;[3] Jafri suggests that he should be suspected of complicity in removing an obstacle to the succession of Yazid.[2][86]

A recent article by Burke et al. examined the circumstances surrounding Hasan's death. Using mineralogical, medical, and chemical evidence, they suggested that the mineral calomel (mercury(I) chloride, Hg2Cl2), sourced from the Byzantine Empire, was the substance primarily responsible for Hasan's death. Because historical sources indicate that another member of Hasan's household also suffered similar symptoms, the article considers Hasan's wife to be the prime suspect. The article cites a historical document, according to which the Byzantine emperor (likely Constantine IV) sent Mu'awiya a poisoned drink at the request of the latter. The authors thus conclude that their forensic hypothesis is consistent with the historical narrative that Hasan was poisoned by his wife, Ja'da, at the instigation of Mu'awiya and with the involvement of the Byzantine emperor.[92]

Burial place

Before his death, Hasan had instructed his family to bury him next to Muhammad; if they "feared evil," however, they were to bury him near his mother in the cemetery of al-Baqi. Sa'id ibn al-'As, the Umayyad governor of Medina, was not opposed to burying Hasan near Muhammad; Marwan strongly objected, arguing that Uthman had been buried in al-Baqi. Aisha also reportedly opposed the burial of Hasan next to Muhammad.[93][89] Abu Hurayra, who had served Mu'awiya,[94] unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Marwan to allow Hasan's burial next to Muhammad by reminding him of Muhammad's high esteem for Hasan and Husayn.[89] Supporters of Husayn and Marwan from the Banu Hashim and Banu Umayyad, respectively, gathered with weapons. Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya reportedly intervened, citing Hasan's burial request to Husayn, and it was decided to bury him in al-Baqi.[89] According to Madelung, Mu'awiya rewarded Marwan for his stand by reinstating him as governor of Medina.[6]

As Hasan's body was carried to al-Baqi, Marwan reportedly joined the procession and paid tribute to a man "whose forbearance (hilm) weighed mountains."[95][96] The governor of Medina, Sa'id ibn al-As, was said to have led the funeral prayer, in line with contemporary customs.[97][98] Hasan's tomb was later made a domed shrine, which was destroyed twice by the Wahhabis: in 1806 and 1927.[lower-alpha 10][6]

Family life

Sources differ about Hasan's wives and children. According to Ibn Sa'd (whose account is considered the most reliable), Hasan had fifteen sons and nine daughters with six wives and three known concubines.[6] His first marriage was to Ja'da bint al-Ash'ath, daughter of the Kinda chief al-Ash'ath ibn Qays, soon after Ali's relocation to Kufa. According to Madelung, Ali intended to establish ties with the powerful Yemeni tribal coalition in Kufa with this marriage. Hasan had no children with Ja'da, who is commonly accused of poisoning him.[99]

Umm Bashir was Hasan's second wife. She was the daughter of Abu Mas'ud Uqba ibn Amr, who had opposed the Kufan revolt against Uthman. Madelung suggests that Ali was hoping to attract Abu Mas'ud to his side with the marriage.[lower-alpha 11][100] Hasan married Khawla bint Manzur ibn Zabban, daughter of the Fazara chief Manzur ibn Zabban, after his abdication and return to Medina.[101] Khawla had been married to Muhammad ibn Talha, who was killed in the Battle of the Camel, and had two sons and a daughter from that marriage. After her father protested that he had been ignored, Hasan presented Khawla to her father and remarried her with his approval.[lower-alpha 12] Khawla bore Hasan his son, Hasan.[102] Hafsa bint Abd al-Rahman was a daughter of Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr, and another wife of Hasan whom he married in Medina.[101] It is said that al-Mundhir ibn al-Zubayr was in love with her, and his rumors compelled Hasan to divorce her. The rumors also ended Hafsa's next marriage, and she eventually married al-Mundhir.[lower-alpha 13][103] Hasan also married Umm Ishaq, daughter of Talha. She was described as beautiful, but with a bad temper. In Damascus, Mu'awiya asked her brother Ishaq ibn Talha to give her in marriage to Yazid but Ishaq married her to Hasan when he returned to Medina, and she bore a son named Talha.[lower-alpha 14][104] Hind bint Suhayl ibn Amr, daughter of Suhayl ibn Amr, was another wife of Hasan.[101] She had been married to Abd al-Rahman ibn Attab (who was killed in the Battle of the Camel) and Abd Allah ibn Amir, who divorced her.[lower-alpha 15] Hasan had no children with Hind.[105]

According to Madelung, Hasan's other children were probably from concubines: Amr ibn Hasan (married and had three children), Qasim and Abu Bakr (both childless and killed in the Battle of Karbala), Abd al-Rahman (childless), al-Husayn, and Abd Allah (possibly identical to Abu Bakr).[106] Late sources add three other offspring: Isma'il, Hamza, and Ya'qub, all of whom were childless. Hasan's daughters from concubines were Umm Abd Allah, who married Zayn al-Abidin and bore Muhammad al-Baqir (the fifth Shia Imam);[107] Fatima and Ruqayya (not known to have married), and Umm Salama (childless).[108]

Other accounts, described by Madelung as absurd, say that Hasan married seventy (or ninety) women in his lifetime and had a harem of three hundred concubines.[6] Pierce wrote that the accusations were by later Sunni writers who were unable to list more than sixteen names.[109] Madelung said that most of the claims were by al-Mada'ini and were often vague; some had a clear defamatory intent.[110] Madelung wrote that the ninety-wives allegation was first made by Muhammad al-Kalbi and was picked up by al-Mada'ini, who was unable to list more than eleven names (five of whom are uncertain or highly doubtful).[111] According to Veccia Vaglieri, the marriages received little contemporary censure.[1]

The number of Hasan's consorts has attracted scholarly attention. Henri Lammens wrote that Hasan married and divorced so frequently that he was called miṭlāq (lit. 'the divorcer'), and his behavior earned Ali new enemies.[112] Madelung disagreed, saying that Hasan – living in his father's household – could not enter into any marriages not arranged (or approved) by Ali.[110] Madelung also wrote that narratives attributed to Ali in which he warns the Kufans not to marry their daughters to Hasan were not credible;[6] Hasan's marriages were intended to strengthen Ali's political alliances, evidenced by Hasan's reservation of his kunya (Muhammad) for his first son with Khawla, his first freely-chosen wife). Madelung wrote that Hasan intended to make Muhammad his primary heir; when he died in childhood, Hasan chose Khawla's second son Hasan.[6]

Allegations of Hasan's readiness to divorce, according to Madelung, indicate no signs of an inordinate sexual appetite,[110] he seemed as noble and forbearing in dealing with his wives as with others.[6] Hasan divorced Hafsa (the granddaughter of Abu Bakr) out of propriety after she was accused by al-Mundhir, although he still loved her. When she married al-Mundhir, Hasan visited the couple and was quick to forgive al-Mundhir for spreading those false rumors out of love for Hafsa.[113] Hasan returned Khawla bint Manzur to her father (who had complained about being ignored), remarrying her with his approval.[110] Madelung cites Hasan's readiness to divorce Hind bint Suhayl when he saw evidence of renewed love by her former husband and his advice to Husayn to marry his widow, Umm Ishaq bint Talha, after his death.[110] When he was poisoned, Hasan reportedly refrained from identifying a suspect to Husayn.[1] Hasan's descendants are usually known as sharif, though the usage of the term is sometimes extended to Husayn's descendants as well.[114]

Assessment and legacy

.jpg.webp)

Hasan has been described as physically resembling Muhammad more than Husayn did. According to Madelung, he might have inherited Muhammad's temperament; Husayn was similar to Ali. Hasan reportedly named two of his sons Muhammad, and had no sons named Ali; Husayn named two of his four sons Ali, and had no sons named Muhammad.[115] In Wilferd Madelung's assessments, Hasan had a pacifist and conciliatory character whereas Husayn inherited his father’s fighting spirit.[115]

According to Momen, Hasan has been criticized by Western historians more than any of the Twelve Imams; he has been called unintelligent, and derided for ceding the caliphate. These criticisms are dismissed by Shia historians who see Hasan's abdication as the only realistic course of action, given the Kufans' fickleness and Mu'awiya's overwhelming military superiority.[46][116] This view is echoed by Veccia Vaglieri, who cites Hasan's love for peace, his distaste for politics and its dissension, and the desire to avoid widespread bloodshed as possible motives for abdication. The statement (attributed to Muhammad), "This son of mine is a lord by means of whom God will one day reunite two great factions of Muslims" might have identified Hasan's abdication as meritorious.[1][117] Hasan was criticized by some contemporary followers, who believed that he had humiliated the Muslims by surrendering the caliphate to Mu'awiya.[1] Jafri attributes the criticism to the group's hatred of Syrian domination.[118]

Representation in Islam

Muslims regard Hasan and Husayn as participants in the event of Mubahala and members of the ahl al-bayt, ahl al-kisa,[12] and Muhammad's love for them has been well-reported;[6] a hadith attributed to Muhammad says that they would be sayyids (lit. 'chiefs') of the youth in Paradise.[lower-alpha 16][1][119] Jami'a al-Tirmidhi (a canonical Sunni hadith collection) notes that, taking Hasan and Husayn by the hand, Muhammad said: "Whoever loves me and loves these two and loves their mother and father, will be with me in my station on the Day of Resurrection."[120] Muhammad is also widely reported to have said, "He who has loved Hasan and Husayn has loved me and he who has hated them has hated me."[119][121] Muhammad allowed the boys to climb on his back while he was prostrate in prayer,[1] and reportedly interrupted a sermon to pick Hasan up after his grandson fell.[1][119]

About Hasan's abdication, historian Dakake said that sources hostile to Hasan interpret his peace treaty with Mu'awiya as a sign of weakness; Hasan intended to surrender from the beginning, and fought half-heartedly.[122] Other sources reject this view, saying that Hasan's abdication was as inevitable after the Kufan mutiny as Ali's acceptance of arbitration; like Ali after Muhammad's death, Hasan was motivated by the desire for unity and peace in the Muslim community.[122] Muhammad reportedly predicted that Hasan would restore peace among the Muslims.[123]

Mu'tazila

Among Muʿtazila Muslims, Hasan's abdication became the source of debates about the possibility of ousting an Imam which were closely related to their view of the legitimacy of Mu'awiya's caliphate. Muʿtazila theologians refused to recognize Mu'awiya caliphate, saying that Hasan remained Imam even after the peace treaty with Mu'awiya. Sunni theologians recognized Mu'awiya's caliphate, however, and regarded the peace treaty as Hasan's resignation from the imamate.[124] According to the Muʿtazila, only a wrong deed by an unrepentant Imam would disqualify him from the imamate after receiving oaths of allegiance; otherwise, an Imam has no right to resign or pledge his allegiance to another person. According to al-Qadi Abd al-Jabbar, based on his ijtihad, Hasan felt that the Kufans would abandon him if he fought Mu'awiya and was compelled to pursue peace.[125] In al-Jubba'i's view, Hasan's reluctant pledge of allegiance to Mu'awiya did not disqualify him from the imamate or legitimize Mu'awiya's caliphate. As a person would not become an infidel if he professes disbelief to save his life, an Imam can pledge allegiance without believing in it. According to al-Jubba'i, others (such as Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, Sa'id ibn Zayd and Abdullah ibn Umar) might have also reluctantly sworn fealty to Mu'awiya. Ibn Mulahmi, a disciple of Abu al-Husayn al-Basri, echoed al-Jubba'i's view of Hasan: "How can it be imagined that Hasan, who planned to fight Mu'awiya to secure his oath of allegiance, would agree to relinquish the caliphate without reluctance?"[125]

Sunni Islam

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelver Shi'ism |

|---|

|

|

During the eighth and ninth centuries, there was a diversity of opinions about which caliphs were "rightly-guided" (rāshidūn), meaning those whose actions and opinions were considered worthy of emulation from a religious point of view.[126] After the ninth century, however, the first four caliphs became canonical in Sunni Islam: Abu Bakr (r. 632–634), Umar (r. 634–644), Uthman (r. 644–656) and Ali (r. 656–661).[127] A fifth caliph, the Umayyad Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (r. 717–720), was cited by ninth-century Sunni hadith collector Abu Dawud al-Sijistani.[128] Another five-caliph hypothesis may have included Hasan as the fifth caliph, whose six-month reign was needed to complete the thirty-year period after Abu Bakr's ascension (reportedly predicted by Muhammad as the length of the prophetic succession). This is also indicated by Abu Dawud al-Tayalisi's version of this narrative, which avoided counting Hasan as the fifth caliph by adding six months to Umar's caliphate.[127]

Sunni Muslims accept Hasan's peace treaty with Mu'awiya with a hadith, attributed to Muhammad, which reportedly predicted that Hasan would unite two warring Muslim parties. By legitimizing Mu'awiya's caliphate, they view the peace treaty as voluntary resignation from the caliphate and imamate; the year of the treaty is called ʿām al-jamāʿa (lit. 'the year of unity') in a number of early Sunni sources.[129][130] According to Sunni Islam, an imam cannot be ousted or resign if he is aware of the divisiveness of his decision; however, he can abdicate if he considers his resignation to be in the best interest of Muslims. Hasan's abdication was a voluntary decision to avoid bloodshed.[125]

Shia Islam

Hasan is regarded by Shia Islam as its second infallible imam, who was designated by his father Ali.[1] He is also venerated because he was born of a divinely-ordained marriage. Shortly after the migration to Medina, Shia sources say that Muhammad followed divine orders and gave Ali his daughter Fatima in marriage.[30] In Shia belief, theirs was the only house that Gabriel allowed to have a door which opened onto the courtyard of The Prophet's Mosque.[123] In Shia Islam, his epithet is al-Mujtaba ("the chosen").[119] Shia theologians have examined the events leading to the peace treaty, citing the disintegration of Hasan's corps, abandonment by his allies, the looting of his military campground, and his assassination attempt as reasons to pursue peace. His infallibility (ismah) as the second Shia imam further justifies this course of action. Sharif al-Murtaza wrote that Hasan reluctantly agreed to peace, and his abdication has been viewed by the Shia as an act of taqiya; he pledged allegiance to Mu'awiya to end the civil war, and Shia theologians have referred to the treaty as a ceasefire (muhādana) or agreement (muʾāhada). According to Shia author Muhammad ibn Bahr al-Shaybani, Mu'awiya did not comply with any of the articles of the treaty (indicating that the compromise was not an alliance). The treaty did not elevate Mu'awiya above Hasan and did not require obedience, evidenced by reports that one condition was that Mu'awiya not be called amir al-mu'minin (lit. 'the commander of the faithful'). This, and reports that Hasan refused to join Mu'awiya in fighting the Kharijites, indicate that he did not recognize Mu'awiya's caliphate.[131]

Imamate

Madelung wrote that although Ali had apparently not nominated a successor before his sudden death, he said several times that only members of Muhammad's household (ahl al-bayt) were entitled to the caliphate. Hasan (whom Ali had appointed his legatee) must have been the obvious choice, and was elected the next caliph soon after Ali's death.[132][1] Ali reportedly regarded Hasan as his waliu'l amr (with his own authority to command), and saw him as his waliu'l dam; avenging Ali's murder was up to Hasan.[133]

In Shia theology, the designation of Hasan as imam was made through nass: the divine decree of Ali. According to a Shia tradition recorded by al-Kulayni, Ali gave al-Jafr and his armor to Hasan in front his family and the Shia leaders before his death and said:

O my son, the Apostle has commanded me to give you the designation and to bequeath to you the secret books and the armor, in the same way that he gave them to me. And when you die you are to give them to your brother Husayn ...[134]

Donaldson wrote that there was originally no significant difference between the divine right of imamate, with each imam designating his successor, and other concepts of succession.[135] Veccia Vaglieri said that Hasan's abdication (criticized by some contemporary followers) has not affected his position as imam in Shia Islam, and is viewed in light of his pious detachment from worldly matters.[1][136] Since the designation of Hasan as imam was made through nass, his imamate could not be annulled by abdication; only the outward function of the caliphate transferred to Mu'awiya.[137] In Shia Islam, the imamate cannot be transferred to another person through allegiance or voluntary resignation.[138] A hadith, attributed to Muhammad and present in Shia and Sunni sources, states that Hasan and Husayn were imams "whether they stand up or sit down" (ascend to the caliphate or not).[lower-alpha 17][139] A hadith, attributed to Muhammad and present in Shia and Sunni sources, states that Hasan and Husayn were imams "whether they stand up or sit down" (ascend to the caliphate or not).[lower-alpha 18][139]

Miracles

According to Donaldson, fewer miracles are attributed to Hasan than to other Shia imams. Veccia Vaglieri disagreed, citing the following: when he was born, Hasan recited the Quran and praised God. Later in life, a dead palm tree produced ripe dates; he fed seventy poor people, and the food did not diminish. Hasan also resurrected a dead man.[140][1]

Literature and TV

Literature

Persian literature inspired by Hasan can be divided into two categories: historical and mystical. Historical literature includes Hasan's life, imamate, his peace with Mu'awiya, and his death. Mystical literature showcases his virtues and his prominent position in Shia spirituality.[141] Hasan's life has been the subject of poetry from Sanai to the present. Themes are his virtues, Muhammad's admiration of him, and his suffering and death. Poets include Sanai (Hadiqat al Haqiqa), Attar of Nishapur, Ghavami Razi, Rumi, 'Ala' al-Dawla Simnani, Ibn Yamin, Khwaju Kermani, Salman Savoji, Hazin Lahiji, Naziri Neyshabouri, Vesal Shirazi, and Adib al-Malak Farahani.[142]

Television

The series Loneliest Leader, directed in 1996 by Mehdi Fakhimzadeh, narrates Hasan's life, his peace with Mu'awiya, and the condition of the Islamic community after his assassination. The events leading up to Hasan's peace and his attempted assassination in al-Mada'in are also mentioned in the series Mokhtarnameh by Davood Mirbagheri.[143] Muawiya, Hasan and Husayn, a series about Hasan and Husayn, has been criticized as anti-Shia.[144]

See also

- The Fourteen Infallibles

Footnotes

- Some sources mentioned 49 (669-70), 50, 48, 58 and 59 AH as the date of death.[1]

- According to some Sunni scholars such as Ibn Asakir and Haythami, Ali had thought of the name of Hamza, Harb, or Jafar - but out of respect for the words of the Prophet, he chose Hasan which, in the form of an adjective, means "good".[8]

- The Christian delegation visited Muhammad to investigate his claims of prophecy and views of Jesus. After an inconclusive debate, Muhammad suggested a Mubahala (prayer curse) in which God would curse whoever was lying. He then reportedly received verse 3:61 of the Quran (known as the Verse of Mubahala), which reads:[10][11][12][13]

If anyone dispute with you in this matter [concerning Jesus] after the knowledge which has come to you, say: Come, let us call our sons and your sons, our women and your women, ourselves and yourselves, then let us swear an oath and place the curse of God on those who lie.[10]

According to Madelung, "our sons" in the verse must refer to Muhammad's grandchildren, Hasan and Husayn, whereas Ali and Fatima (their parents) could reasonably be included in the event.[14] Of those present, Shia narratives of the event are unanimous that "our women" refers to Fatima; "ourselves" refers to Ali, on Muhammad's side.[15] Most Sunni narratives quoted by al-Tabari do not name the participants in the event. Other Sunni historians say that Muhammad, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn participated in the Mubahala, and some agree with the Shia tradition that Ali was among them.[14][11][13] Some accounts of the event of Mubahala add that Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn stood under Muhammad's cloak, and they are known as the ahl al-kisa ("family of the cloak").[16][17] - The ahl al-bayt were also praised in the Quran's Verse of Purification: "God desires only to remove defilement from you, o ahl al-bayt, and to purify you completely."[18]

- In a letter to Mu'awiya I, which Madelung quoted, Hasan echoed Ali's views on usurping the caliphate from the ahl al-bayt following Muhammad's death.[27]

- 1) That the caliphate would be restored to Hasan after the death of Mu'awiya, 2) that Hasan would receive five million dirhams annually from the state treasury, 3) that Hasan would receive the annual revenue of Darabjird, 4) that the people would be guaranteed peace with one another.[72]

- 1) That Mu'awiya should rule according to the Book of God, the sunna of the Prophet, and the conduct of the righteous caliphs, 2) that Mu'awiya would not appoint or nominate anyone to the caliphate after him, but the choice would be left to a shura, 3) that the people would be left in peace wherever they are in the land of God, 4) that the companions and the followers of Ali, their lives, properties, their women and their children, would be guaranteed safe conduct and peace, 5) that no harm or dangerous act, secretly or openly, would be done to Hasan, his brother, Husayn, or to anyone from the family of the Muhammad.[73]

- Other sources mentioned 49 (669-70), 50, 48, 58 and 59 AH.[1]

- Madelung writes that this view is also accepted by the major Sunni historians al-Waqidi, al-Mada'ini, Umar ibn Shabba, al-Baladhuri, and Haytham ibn Adi.[86]

- In Wahhabi belief, historical sites and shrines encourage shirk – the sin of idolatry or polytheism – and should be destroyed. See Taylor, Jerome (24 September 2011). "Mecca for the rich: Islam's holiest site 'turning into Vegas'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017..

- During his involvement in the Battle of Siffin, Ali appointed Abu Mas'ud as the governor of Kufa. Hasan had two (or three) children with Umm Bashir: his eldest son Zayd, his daughter Umm al-Husayn, and probably another daughter named Umm al-Hasan; see (Madelung 1997, p. 381.

- Madelung writes that she was either given in marriage to Hasan by Abd Allah ibn Zubayr (who was married to her sister), or Khawla gave Hasan the choice of marrying her. Hearing this, her father said that he would not be ignored concerning his daughter. He came to Medina and protested; Hasan gave her to him, and he brought her to Quba. Khawla reproached her father, reminding him of Muhammad's saying that Hasan would be lord of the youth in Paradise. He told her, "Wait here, if the man is in need of you, he will join us here." Hasan joined them with some of his relatives, took her back and remarried her with her father's consent; see Madelung 1997, pp. 381, 382.

- After divorcing Hasan, Asim (son of Umar) married her. Al-Mundhir accused her before Asim, who also divorced her. Al-Mundhir proposed to her, but she turned him down. Hafsa was later persuaded to marry him to prove the falsehood of the rumors against her. See Madelung 1997, p. 382.

- Hasan asked his younger brother, Husayn, to marry her after his death. Husayn did so, and had a daughter named Fatima. See Madelung 1997, p. 383.

- Hind reportedly said about her three husbands, "The lord (sayyid) of them was Hasan, the most generous of them was Ibn 'Amir, and the one dearest to me was 'Abd al-Rahman bin 'Attab." See Madelung 1997, pp. 383, 384.

- The authenticity of this hadith was disputed by the Umayyad Marwan ibn Hakam.

- See also Irshad, p. 181; Ithbat al-hudat, vol. V, pp. 129 and 134.

- See also Irshad, p. 181; Ithbat al-hudat, vol. V, pp. 129 and 134.

References

Notes

Citations

- Vaglieri 1971.

- Momen 1985, p. 28.

- Jafri 1979, p. 158.

- Melchert 2020, pp. 70, 71.

- Browne 1928, p. 392.

- Madelung 2003.

- Poonawala & Kohlberg 1985.

- Haj-Manouchehri 2013, p. 532.

- Vaglieri 1971, p. 240.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 15, 16.

- Momen 1985, p. 14.

- Momen 1985, pp. 13, 14.

- Bar-Asher & Kofsky 2002, p. 141.

- Madelung 1997, p. 16.

- Mavani 2013, pp. 71, 72.

- Momen 1985, pp. 14, 16, 17.

- Algar 1984.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 14, 15.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 203, 204.

- Campo 2004.

- Mavani 2013, p. 41.

- Campo 2009.

- Britannica 2022.

- Schroeder 2002, p. 177.

- Humphreys 1990, p. 42.

- Vaglieri 1960.

- Madelung 1997, p. 314.

- Vaglieri 1991.

- Jafri 1979, p. 62.

- Nasr & Afsaruddin 2021.

- Glassé 2002, p. 423.

- Haj-Manouchehri 2013, p. 534.

- Madelung 1997, p. 165.

- Hulmes 2013, p. 218.

- Haj-Manouchehri 2013, p. 535.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 102–103.

- Wellhausen 1901, p. 18.

- Momen 1985, pp. 26–7.

- Jafri 1979, p. 91.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 311–2.

- Jafri 1979, p. 133.

- Dakake 2008, p. 74.

- Madelung 1997, p. 312.

- Madelung 1997, p. 317.

- Jafri 1979, p. 134.

- Momen 1985, p. 27.

- Jafri 1979, p. 135.

- Jafri 1979, p. 136.

- Jafri 1979, p. 137.

- Madelung 1997, p. 318.

- Jafri 1979, p. 142.

- Anthony 2013, p. 229.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 105.

- Jafri 1979, p. 101.

- Donaldson 1933, p. 69.

- Madelung 1997, p. 319.

- Jafri 1979, p. 145.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 106–7.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 27–8.

- Madelung 1997, p. 320.

- Jafri 1979, p. 146.

- Lalani 2000, p. 4.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 106.

- Madelung 1997, p. 321.

- Madelung 1997, p. 322.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 322–3.

- Madelung 1997, p. 323.

- Donaldson 1933, pp. 66–78.

- Jafri 1979, p. 153.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 105–8.

- Jafri 1979, p. 149.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 150, 151.

- Jafri 1979, p. 151.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 150–2.

- Jafri 1979, p. 152.

- Madelung 1997, p. 325.

- Madelung 1997, p. 324.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 324–5.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 157, 158.

- Momen 1985, pp. 27, 28.

- Jafri 1979, p. 157.

- Madelung 1997, p. 327.

- Madelung 1997, p. 328.

- Madelung 1997, p. 331–332.

- Donaldson 1933, pp. 76, 77.

- Madelung 1997, p. 331.

- Pierce 2016, p. 83.

- Ahmed 2011, p. 143.

- Madelung 1997, p. 332.

- Rippin & Knappert 1990, p. 139.

- Liaw 2013, p. 226.

- Burke et al. 2016.

- Pierce 2016, p. 80.

- Madelung 1997, p. 287.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 332–333.

- Donaldson 1933, p. 78.

- Madelung 1997, p. 333.

- Halevi 2011, p. 173.

- Madelung 1997, p. 380.

- Madelung 1997, p. 381.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- Madelung 1997, pp. 381, 382.

- Madelung 1997, p. 382

- Madelung 1997, p. 383.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 383, 384.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- Pierce 2016, p. 135.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 384, 385.

- Pierce 2016, p. 84.

- Madelung 1997, p. 385.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 386, 387.

- Lammens 1927, p. 274.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 382, 385.

- Bowering et al. 2013, p. 190.

- Madelung 2004.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 109, 110.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 110, 111.

- Jafri 1979, p. 110.

- Momen 1985, p. 26.

- Momen 1985, p. 15.

- Pierce 2016, p. 70.

- Dakake 2008, pp. 74, 75.

- Donaldson 1933, p. 73.

- Paktchi 2013, pp. 558–559.

- Paktchi 2013, p. 559.

- Melchert 2020, pp. 63–64.

- Melchert 2020, p. 71.

- Melchert 2020, p. 70.

- Hinds 1993, p. 265.

- Marsham 2013, p. 93.

- Paktchi 2013, p. 558.

- Madelung 1997, p. 311.

- Donaldson 1933, p. 68.

- Donaldson 1933, pp. 67–68.

- Donaldson 1933, p. 66.

- Anthony 2013.

- Paktchi 2013.

- Paktchi 2013, pp. 557–558.

- Tabatabai 1977, p. 173.

- Donaldson 1933, pp. 74, 75.

- Paktchi 2013, p. 561.

- Paktchi 2013, pp. 561–562.

- Fayazi, Kia. Critique of Mokhtarnameh serial (PDF) (in Persian).

- "'Al-Hassan and al-Hussein' TV drama: An orthodox narrative in a progressive form". Egypt Independent. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

Sources

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2011). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Occasional Publications UPR. ISBN 978-1900934138.

- Algar, H (1984). "Āl–e ʿAbā". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation.

- Anthony, Sean W. (2013). "Ali b. Abi Talib". In Bowering, Gerhard (ed.). The Princeton encyclopedia of Islamic political thought. Princeton University Press. pp. 30–31.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022). "Hasan". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Bar-Asher, Meir M.; Kofsky, Aryeh (2002). The Nusayri-Alawi Religion: An Enquiry into Its Theology and Liturgy. Brill. ISBN 978-9004125520.

- Bowering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad; Mirza, Mahan; Stewart, Devin J.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69-113484-0.

- Browne, Edward Granville (1928). A Literary History of Persia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780936347622.

- Burke, Nicole; Golas, Mitchell; Raafat, Cyrus L.; Mousavi, Aliyar (July 2016). "A forensic hypothesis for the mystery of al-Hasan's death in the 7th century: Mercury(I) chloride intoxication". Medicine, Science and the Law. 56 (3): 167–171. doi:10.1177/0025802415601456. ISSN 0025-8024. PMC 4923806. PMID 26377933.

- Campo, J.E. (2009). "ahl al-bayt". Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts On File, Inc. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- Campo, J.E. (2004). "AHL AL-BAYT". In Martin, R.C. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world. Macmillan Reference. pp. 25, 26.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2008). Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (ed.). The Charismatic Community: Shi'ite Identity in Early Islam. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7033-6.

- Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press.

- Dixon, Abd al-Ameer A. (1971). The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (a Political Study). London: Luzac. ISBN 978-0718901493.

- Glassé, Cyril (2002). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Tian Wah Press. p. 423. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6.

- Halevi, Leor (2011). Muhammad's Grave: Death Rites and the Making of Islamic Society. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231137430.

- Hinds, Martin (1993). "Muʿāwiya I b. Abī Sufyān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 263–268. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XV: The Crisis of the Early Caliphate: The Reign of ʿUthmān, A.D. 644–656/A.H. 24–35. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0154-5.

- Jafri, S. M. (1979). Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam. London and New York: Longman. ISBN 9780582780804.

- Lalani, Arzina R. (2000). Early Shi'i Thought: The Teachings of Imam Muhammad Al-Baqir. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1860644344.

- Lammens, Henri (1927). "Al-Ḥasan b. 'Ali b. Abï Ṭālib". In Houtsma, M. Th.; Wesinck, A. J.; Arnold, T. W.; Heffening, W.; Lévi-Provençal, E. (eds.). The Encyclopædia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples. Vol. 2. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 274. OCLC 1008303874.

- Liaw, Yock Fang (2013). A History of Classical Malay Literature. Institute of Southeast Asian. ISBN 9789814459884.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64696-3.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2003). "ḤASAN B. ʿALI B. ABI ṬĀLEB". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2004). "Ḥosayn b. ʿAli i. Life and Significance in Shiʿism". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XII. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 493–498.

- Marsham, Andrew (2013). "The Architecture of Allegiance in Early Islamic Late Antiquity: The Accession of Mu'awiya in Jerusalem, ca. 661 CE". In Beihammer, Alexander; Constantinou, Stavroula; Parani, Maria (eds.). Court Ceremonies and Rituals of Power in Byzantium and the Medieval Mediterranean. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 87–114. ISBN 978-90-04-25686-6.

- Mavani, Hamid (2013). Religious Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Shi'ism: From Ali to Post-Khomeini. Routledge. ISBN 9780415624404.

- Melchert, Christopher (2020). "The Rightly Guided Caliphs: The Range of Views Preserved in Ḥadīth". In al-Sarhan, Saud (ed.). Political Quietism in Islam: Sunni and Shi'i Practice and Thought. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. pp. 63–79. ISBN 978-1-83860-765-4.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03531-5.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Afsaruddin, Asma (2021). "Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Hulmes, Edward D. A. (2013). "Al-Hasan Ibn 'Ali Ibn Abi Talib (c. AD 625-690)". In Netton, Ian Richard (ed.). Encyclopædia of Islamic Civilisation and Religion. Routledge. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-0700715886.

- Pierce, Matthew (2016). Twelve Infallible Men: The Imams and the Making of Shi'ism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674737075.

- Poonawala, Ismail; Kohlberg, Etan (1985). "ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭāleb". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 1. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 838–848.

- Rippin, Andrew; Knappert, Jan (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Islam. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226720630.

- Schroeder, Eric (2002). Muhammad's People: An Anthology of Muslim Civilization. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486425023.

- Tabatabai, Sayyid Muhammad Husayn (1977). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Seyyed Hossein Nasr. SUNY press. ISBN 0-87395-390-8.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1960). "ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 381–386. OCLC 495469456.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1971). "(Al)-Ḥasan b. ʿAlï b. Abï Ṭālib". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 240–243. OCLC 495469525.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1991). "Al-Djamal". In Bearman, p. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). E. J. Brill.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1901). Die religiös-politischen Oppositionsparteien im alten Islam (in German). Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. OCLC 453206240.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

- Paktchi, Ahmad; Tareh, Masoud; Haj-Manouchehri, Faramarz; Masoudi Arani, Abdullah (2013). Mousavi-Bojnourdi, Mohammad-Kazem (ed.). Hassan (AS), Imam (in Persian). Tehran: Encyclopaedia Islamica. pp. 532–565. ISBN 978-600-6326-19-1.

External links

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hasan and Hosein". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hasan and Hosein". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.