History of Carthage

The city of Carthage was founded in the 9th century BC on the coast of Northwest Africa, in what is now Tunisia, as one of a number of Phoenician settlements in the western Mediterranean created to facilitate trade from the city of Tyre on the coast of what is now Lebanon. The name of both the city and the wider republic that grew out of it, Carthage developed into a significant trading empire throughout the Mediterranean. The date from which Carthage can be counted as an independent power cannot exactly be determined, and probably nothing distinguished Carthage from the other Phoenician colonies in Northwest Africa and the Mediterranean during 800–700 BC. By the end of the 7th century BC, Carthage was becoming one of the leading commercial centres of the West Mediterranean region. After a long conflict with the emerging Roman Republic, known as the Punic Wars (264–146 BC), Rome finally destroyed Carthage in 146 BC. A Roman Carthage was established on the ruins of the first. Roman Carthage was eventually destroyed—its walls torn down, its water supply cut off, and its harbours made unusable—following its conquest by Arab invaders at the close of the 7th century.[1] It was replaced by Tunis as the major regional centre, which has spread to include the ancient site of Carthage in a modern suburb.

Beginning

Carthage was one of a number of Phoenician settlements in the western Mediterranean that were created to facilitate trade from the cities of Sidon, Tyre and others from Phoenicia, which was situated in the coast of what is now Lebanon. In the 10th century BC, the eastern Mediterranean shore was inhabited by various Semitic populations, who had built up flourishing civilizations. The people inhabiting what is now Lebanon were referred to as Phoenicians by the Greeks. The Phoenician language was very close to ancient Hebrew, to such a degree that the latter is often used as an aid in the translation of Phoenician inscriptions.

The Phoenician cities were highly dependent on both land- and seaborne trade and their cities included a number of major ports in the area. In order to provide a resting place for their merchant fleets, to maintain a Phoenician monopoly on an area's natural resource, or to conduct trade on its own, the Phoenicians established numerous colonial cities along the coasts of the Mediterranean, stretching from Iberia to the Black Sea. They were stimulated to found their cities by a need for revitalizing trade in order to pay the tribute extracted from Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos by the succession of empires that ruled them and later by fear of complete Greek colonization of that part of the Mediterranean suitable for commerce. The initial Phoenician colonization took place during a time when other neighboring kingdoms (Hellenic/Greek and Hattian/Hittite) were suffering from a "Dark Age", perhaps after the activities of the Sea Peoples. The city of Carthage initially covered the area around a hill called Byrsa, paid an annual tribute to the nearby Libyan tribes, and may have been ruled by a governor from Tyre, whom the Greeks identified as "king". Utica, then the leading Phoenician city in Northwest Africa, aided the early settlement in her dealings.

The Phoenicians' leading city was Tyre, which established a number of trading posts around the Mediterranean. Ultimately Phoenicians established 300 colonies in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Iberia, and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya. The Phoenicians lacked the population or necessity to establish self-sustaining cities abroad, and most cities had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, but Carthage and a few other cities later developed into large, self-sustaining, independent cities. The Phoenicians controlled Cyprus, Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands, as well as obtaining minor possessions in Crete and Sicily; the latter settlements were in perpetual conflict with the Greeks. The Phoenicians managed to control Sicily for a limited time, but Phoenician control did not extend inland and was limited to the coast only.

The first colonies were made on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth—along with the African coast and on Sicily, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. The center of the Phoenician world was Tyre, serving as an economic and political hub. The power of this city waned following numerous sieges and its eventual destruction by Alexander the Great, and the role as leader passed to Sidon, and eventually to Carthage. Each colony paid tribute to either Tyre or Sidon, but neither mother city had actual control of the colonies. This changed with the rise of Carthage since the Carthaginians appointed their own magistrates to rule the towns and Carthage retained much direct control over the colonies. This policy resulted in a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars.

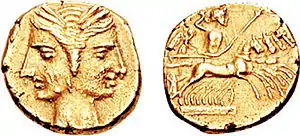

Ancient sources concur that Carthage had become perhaps the wealthiest city in the world via its trade and commerce, yet few remains of its riches exist. This is due to the fact that most of it was short-lived materials—textiles, unworked metal, foodstuffs, and slaves; its trade in fabricated goods was only a part of its wares. There can be no doubt that the most fruitful trade was that acquired from the Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean, in which tin, silver, gold, and iron were gained in return for consumer goods.[2] Like their Phoenician predecessors the Carthaginians produced and exported the very valuable Tyrian purple dye that was extracted from shellfish.[3] The Phoenician colony of Mogador on the northwestern coast of Africa was a center of Tyrian dye production.[4]

Dido and the foundation of Carthage

Carthage was founded by Phoenicians coming from the Levant. The city's name in Phoenician language means "New City".[5] There is a tradition in some ancient sources, such as Philistos of Syracuse, for an "early" foundation date of around 1215 BC – that is before the fall of Troy in 1180 BC; however, Timaeus of Taormina, a Greek historian from Sicily c. 300 BC, gives the foundation date of Carthage as thirty-eight years before the first Olympiad; this "late" foundation date of 814 BC is the one generally accepted by modern historians.[6][7] As such, Utica predates Carthage. The name Utica is derived from a Punic stem 'dtāq, meaning "to be old",[8] which lends some support to this chronology, for Carthage signifies "new city" (as stated above). The fleets of the King Hiram of Tyre, as recounted in the Bible, perhaps joined at times by ships assigned to Solomon, would date to the 10th century. "For the king had a fleet of ships of Tarshish at sea with the fleet of Hiram."[9][10][11][12] The Punic port city of Utica was originally situated at the mouth of the fertile Wadi Majardah (Medjerda River),[13] at a point along the coast about 30 kilometres north of Carthage.[14] "Utica is named besides Carthage in the second treaty with Rome (348), and... appears again as nominally equal with Carthage in the treaty between Hannibal and Philip of Macedon (215). She does not appear in the first treaty with Rome (508), which perhaps means she was fully independent and not even bound in the Carthage-Rome alliance."[15] Of course, eventually Utica was surpassed by Carthage.

Tyre, the major maritime city-state of Phoenicia and prime mover in the Phoenician mercantile expansion into the western Mediterranean, first settled Carthage. Probably Carthage started as one of Tyre's permanent stations en route to its very profitable, ongoing trade in metals with southern Hispania.[16] Such stations were often established by Tyre at intervals of about 30 to 50 kilometres along the African coast.[17] Carthage would grow to out-rival all other Phoenician settlements.

Legends alive in the city for centuries assigned its foundation in 814 BC to a queen of Tyre, Elissa, also called Dido ("beloved").[18][19][20] Dido's great aunt must have been Jezebel, who was also the daughter of a King of Tyre, in this case Ithobaal [the biblical Ethbaal] (r. 891–859); Jezebel became wife to King Ahab of Israel (r. 875–853), according to the Hebrew Books of Kings.[21][22][23][24][25]

Dido's story is told by the Roman historian Pompeius Trogus (1st century BC), a near contemporary of Virgil. Trogus describes a sinister web of court intrigue in which the new king Pygmalion[26] (brother of Dido) slays the chief priest Acharbas (husband of Dido), which causes the Queen Elissa (Dido) along with some nobles to flee the city of Tyre westward in a fleet of ships carrying royal gold.[27][28] At Cyprus, four score temple maidens were taken aboard the ships.[29][30] Then her fleet continues on, landing in Northwest Africa to found Carthage. Shortly after becoming established, according to Trogus, it is said that Hiarbus, a local Mauritani tribal chief, sought to marry the newly arrived queen.[31] Instead, in order to honour her murdered husband the priest, Dido took her own life by the sword, publicly casting herself into a ceremonial fire. Thereafter she was celebrated as a goddess at Carthage.[32][33][34]

The Roman poet Virgil (70–19 BC) presents Dido as a tragic heroine in his epic poem the Aeneid, whose hero Aeneas travels from Troy, to Carthage, to Rome.[35] The work contains inventive scenes, loosely based on the legendary history of Carthage, e.g., referring to the then well-known story how the Phoenician Queen cunningly acquired the citadel of the Byrsa.[36][37][38] In Virgil's epic, the god Jupiter requires the hero Aeneas to leave his beloved Dido, who then commits suicide and burns in a funeral pyre.[39] This episode employs not only the history or legends narrated by Trogus (mentioned above), but perhaps also subsequent mythical and cult-based elements, as Dido would become assimilated to the Punic or Berber goddess Tanit. Each autumn a pyre was built outside the old city of Carthage; into it the goddess was thought to throw herself in self-immolation for the sake of the dead vegetation god Adonis–Eshmun.[40][41]

"Nothing of historical value can be derived from the foundation legends transmitted to us in various versions by Greek and Roman authors", comments professor Warmington.[42][43] Yet from such legends the modern reader may form some understanding of how the ancient people of Carthage spoke to each other about their city's beginnings, i.e., an aspect of their collective self-image, or perhaps even infer some of the subtlety in the cultural context of the accepted tradition, if not the personality of the characters nor the gist of the events themselves.[44]

The 6th century Hebrew prophet Ezekiel in a lamentation nonetheless sings the praises of the Phoenicians, specifically of the cities of Tyre and Sidon.[45][46] "Tyre, who dwells at the entrance to the sea, merchant of many peoples on many coastlands... . ... Tarshish trafficked with you because of your great wealth of every kind; silver, iron, tin, and lead they exchanged for your wares."[47][48] Homer describes such a Phoenician ship in the Odyssey.[49][50]

Modern consensus locates this ancient, mineral-rich region (called Tarshish [TRSYS] by Ezekiel) in the south of Hispania,[51][52] possibly linked to Tartessos, a native city of the Iberians.[53] Here mining was already underway, and early on the Phoenicians founded the city of Gadir (Phoenician GDR strong wall) (Latin Gades) (currently Cádiz).[54][55] Bronze then was a highly useful and popular material, made from copper and tin. Tin being scarce though in high demand, its supply became very profitable.[56] Yet Hispania was even more rich in silver. Originally Carthage was probably a stop on the way between Tyre and the region of Gadir, a stop where sailors might beach their boats and resupply with food and water.[57] Eventually, local trade would begin, and huts built; later more permanent homes and warehouses constructed, then fortified, perhaps also a shrine. All would change and transform on the day when a Queen of Tyre arrived with a fleet of ships, carrying nobility and well-connected merchants, and royal treasure.[58]

Carthage was founded by Phoenician settlers from the city of Tyre, who brought with them the city-god Melqart. Philistos of Syracuse dates the founding of Carthage to c 1215 BC, while the Roman historian Appian dates the founding 50 years prior to the Trojan War (i.e. between 1244 and 1234 BC, according to the chronology of Eratosthenes). The Roman poet Virgil imagines that the city's founding coincides with the end of the Trojan War. However, it is most likely that the city was founded sometime between 846 and 813 BC.[59]

Colony of Tyre

Little is known of the internal history and dealings of the early Phoenician city. The initial city covered the area around Byrsa, paid an annual tribute to the nearby Libyan tribes, and may have been ruled by a governor from Tyre, whom the Greeks identified as "king". Utica, then the leading Phoenician city in Africa, aided the early settlement in her dealings. The date from which Carthage can be counted as an independent power cannot exactly be determined, and probably nothing distinguished Carthage from the other Phoenician colonies in Africa during 800–700 BC.

It has been noted that the culture of Phoenician colonies had gained a distinct "Punic" character by the end of the 7th century BC, indicating the emergence of a distinct culture in Western Mediterranean.[60] In 650 BC, Carthage planted her own colony,[61] and in 600 BC, she was warring with Greeks on her own away from the African mainland. By the time King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon was conducting the 13-year siege of Tyre starting from 585 BC, Carthage was probably independent of her mother city in political matters. However, close ties with Tyre still remained, Carthage continued to send annual tribute to Tyre (for the temple of Melqart) at irregular intervals over the centuries. Carthage inherited no colonial empire from Tyre and had to build her own. It is likely that Carthage did not have an empire prior to 6th century BC.

Exactly what social/political/geographic/military factors influenced the citizens of Carthage, and not the other Mediterranean Phoenician colonial members to create an economic and political hegemony is not clearly known. The city of Utica was far older than Carthage and enjoyed the same geographical/political advantages as Carthage, but it opted to be an allied entity, not a leader of the Punic hegemony that came into being probably sometime around the 6th century BC. When the Phoenician trade monopoly was challenged by Etruscans and Greeks in the west and their political and economic independence by successive empires in the east, Phoenician influence from the mainland decreased in the west and Punic Carthage ultimately emerged at the head of a commercial empire. One theory is that refugees from Phoenicia swelled the population and enhanced the culture of Carthage during the time the Phoenician homeland came under attack from the Babylonians and Persians, transferring the tradition of Tyre to Carthage.[62]

Beginning of Carthaginian hegemony

The mainland Greeks began their colonization efforts in the western Mediterranean with the founding of Naxos and Cumae in Sicily and Italy respectively, and by 650 BC Phoenicians in Sicily had retreated to the western part of that island. Around this time the first recorded independent action by Carthage takes place, which is the colonization of Ibiza. By the end of the 7th century BC, Carthage was becoming one of the leading commercial centres of the West Mediterranean region, a position it retained until overthrown by the Roman Republic. Carthage would establish new colonies, repopulate old Phoenician ones, come to the defence of other Punic cities under threat from natives/Greeks, as well as expand her territories by conquest. While some Phoenician colonies willingly submitted to Carthage, paying tribute and giving up their foreign policy, others in Iberia and Sardinia resisted Carthaginian efforts.

Carthage, unlike Rome, did not concentrate on conquering lands adjacent to the city prior to embarking on overseas ventures. Her dependence on trade and focus on protecting that trade network saw the evolution of an overseas hegemony before Carthage pushed inland into Africa. It may be possible that the power of the Libyan tribes prevented expansion in the neighbourhood of the city for some time.[63] Until 550 BC, Carthage paid rent to the Libyans for use of land in the city surroundings[64] and in Cape Bon for agricultural purposes. The Africa dominion controlled by Carthage was relatively small. The payment would be finally stopped around 450 BC, when the second major expansion inland into Tunisia would take place. Carthage probably colonized the Syrtis region (Area between Thapsus in Tunisia and Sabratha in Libya) between 700–600 BC. Carthage also focused on bringing the existing Phoenician colonies along the African coast into the hegemony, but exact details are lacking. Emporia had fallen under Carthaginian influence prior to 509 BC, as the first treaty with Rome indicated. The eastward expansion of Carthaginian influence along the African coast (through what is now Libya) was blocked by the Greek colony of Cyrene (established 630 BC).

Carthage spread her influence along the west coast relatively unhindered, but the chronology is unknown. Wars with the Libyans, Numidians and Mauri took place but did not end with the creation of a Carthaginian empire. The degree of control Carthage exerted over her territories varied in their severity. In ways, the Carthaginian hegemony shared some of the characteristics of the Delian League (allies sharing defence expenditure), the Spartan Kingdom (serfs tilling for the Punic elite and state) and to a lesser extent, the Roman Republic (allies contributing manpower/tribute to furnish the Roman war machine). The African lands near to the city faced the harshest control measures, with Carthaginian officers administering the area and Punic troops garrisoning the cities. Many cities had to destroy their defensive walls, while the Libyans living in the area had few rights. The Libyans could own land, but had to pay an annual tribute (50% of agricultural produce and 25% of their town income) and serve in the Carthaginian armies as conscripts.[65]

Other Phoenician cities (Like Leptis Magna) paid an annual tribute and ran their own internal affairs, retained their defensive walls but had no independent foreign policy. Other cities had to provide personnel for the Punic army and the Punic navy along with tribute but retained internal autonomy. Allies like Utica and Gades were more independent and had their own government. Carthage stationed troops and some type of central administration in Sardinia and Iberia to control her domain. The cities, in return for surrendering these privileges, obtained Carthaginian protection, which provided the fleet to combat piracy and fought wars needed to protect these cities from external threats.

Carthaginian citizenship was more exclusive, and the goal of the state was more focused on protecting the trade infrastructure than expanding the citizen body. This contrasts with the Roman Republic, which in the course of her wars created an alliance system in Italy that expanded her lands and also expanded her citizen body and military manpower by adding allies (with varying degrees of political rights). Carthage, while she continued to expand until 218 BC, did not have a similar system to increase her citizen numbers. She had treaties in place with various Punic and non-Punic cities (the most famous and well known ones being the ones with Rome), detailing the rights of each power and their sphere of influence. The Punic cities not under direct Carthaginian control probably had similar treaties in place. The Libyo-Phoenicians, who lived in the African domain controlled by Carthage, also had rights similar to those of Carthaginian citizens. Carthaginian citizens were exempt from taxation and were primarily involved in commerce as traders or industrial workers. As a result, Carthage, unlike the other agricultural nations, could not afford to have her citizens serve in a long war, as it diminished her commercial activities.

Reign of kings

Carthage was initially ruled by kings, who were elected by the Carthaginian senate and served for a specific time period. The election took place in Carthage, and the kings at first were war leaders, civic administrators and performed certain religious duties. According to Aristotle, kings were elected on merit, not by the people but by the senate, and the post was not hereditary. However, the crown and military commands could also be purchased by the highest bidder. Initially these kings may have enjoyed near absolute power, which was curtailed as Carthage moved towards a more democratic government. Gradually, military command fell to professional officers, and a pair of suffets replaced the king in some of the civic functions and eventually kings were no longer elected. Records show that two families had held the kingship with distinction during 550–310 BC. The Magonid family produced several members who were elected kings between 550 BC and 370 BC, who were in the forefront of the overseas expansion of Carthage. Hanno "Magnus", along with his son and grandson, held the kingship for some years between 367 and 310 BC. Records of other elected kings or their impact on Carthaginian history are not available. The suffets, who would ultimately displace the kings, were elected by the people. Suffets would ultimately discard their military duties and become purely civic officials.

The Phoenicians encountered little resistance in developing their trade monopoly during 1100–900 BC. The emergence of the Etruscans as a sea power did little to dent the Phoenician trade. The power of the Etruscans was localized around Italy, and their trade with Corsica, Sardinia and Iberia had not hindered Phoenician activity. Trade had also developed between Punic and Etruscan cities, and Carthage had treaties with the Etruscan cities to regulate these activities, while mutual piracy had not led to full-blown war between the powers. Carthage's economic successes, and its dependence on shipping to conduct most of its trade, led to the creation of a powerful Carthaginian navy to discourage both pirates and rival nations. This, coupled with its success and growing hegemony, ultimately brought Carthage into increasing conflict with the Greeks, the other major power contending for control of the central Mediterranean. In conducting these conflicts, which spanned between 600–310 BC, the overseas empire of Carthage also came into being under the military leadership of the "kings". The Etruscans, also in conflict with the Greeks, became allies of Carthage in the ensuing struggle.

By the middle of the 6th century BC, Carthage had grown into a fully independent thalassocracy. Under Mago (r., c.550–530) and later his Magonid family, Carthage became pre-eminent among the Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean, which included nearby Utica. Mago, the 6th century ruler of Carthage, initiated the practice of recruiting the army from subject peoples and mercenaries, because "the population of Carthage was too small to provide defence for so widely scattered an empire." Hence, Libyans, Iberians, Sardinians, and Corsicans were soon enlisted.[66]

The commercial territories regularly visited by Punic traders encompassed all the western maritime region. Trading partnerships were established nearby, among the Numidian Berbers to the west along the African coast as well as to the east with Berbers in Libya. Carthage founded many trading stations in the western Mediterranean, which often developed into cities. Island posts included: Palermo in western Sicily, Nora in southern Sardinia, Ibiza in the Balearics. In the Iberian peninsula: Cartagena and other posts along its south and east coasts, including Gades north of the straits on the Atlantic side. South of the straits was Lixus in Mauretania. Further, Carthage enjoyed an alliance with the Etruscans, who had established a powerful state in north-west Italy. Among the clients of the Etruscans was the then infant city of Rome. A 6th century Punic-Etruscan treaty reserved for Carthage a commercial monopoly in southern Iberia.[67][68][69][70]

Punic ships sailed into the Atlantic. A merchant sailor of Carthage, Himilco, explored in the Atlantic to the north of the straits, i.e., along the coast of the Lusitanians and perhaps as far north as Oestrymnis (modern Brittany), c. 500 BC. Carthage would soon supplant the Iberian city of Tartessus in carrying the tin trade from Oestrymnis southward into the Mediterranean. Another sailor, Hanno the Navigator, explored the Atlantic to the south, along the African coast well past the River Gambia. The traders of Carthage were known to be secretive about business and particularly about trade routes; it was their practice to keep the straits to the Atlantic closed to the Greeks.[71][72]

Conflict with the Greeks

The nature of the conflict between Carthage and the Greeks was more due to economic factors rather than ideological and cultural differences. The Greeks did not wage a crusade to save the world from Imperium Barbaricum but to extend their own area of influence, neither was Carthage interested in wiping out Greek ideals. It was the vulnerability of the Carthaginian economy to Greek commercial competition that caused Carthage to take on the Greeks during the early years of her empire.

The trade network which Carthage inherited from Tyre depended heavily on Carthage keeping commercial rivals at arm's length. The goods produced by Carthage were mainly for the local African market and were initially inferior to Greek goods.[73] Carthage was the middleman between mineral resource-rich Iberia and the east. She bartered low-priced goods for metals, then bartered those for finished goods in the east and distributed these through their network. The threat from the Greek colonists was threefold: undercutting the Phoenicians by offering better products; taking over the distribution network; and preying on Punic shipping. While the Greek colonies also offered increased opportunities for trade and piracy, their nosing into areas of Punic influence caused the Punic cities to look for protection from their strongest city. Carthage took up the challenge.

The Greek colonization in the Western Mediterranean started with the establishment of Cumae in Italy and Naxos in Sicily after 750 BC. Over the next century, hundreds of Greek colonies sprang up along the Southern Italian and Sicilian coastlines (except Western Sicily). There are no records of Phoenicians initially clashing with Greeks over territory; in fact, the Phoenicians had withdrawn to the Western corner of Sicily in the face of Greek expansion. However, the situation changed sometime after 638 BC, when the first Greek trader visited Tartessos, and by 600 BC Carthage was actively warring with the Greeks to curb their colonial expansion. By 600 BC, the once-Phoenician lake had turned into a conflict zone with the Greeks rowing about in all corners. Carthaginian interests in Iberia, Sardinia and Sicily were threatened, which led to a series of conflicts between Carthage and various Greek city-states.

Twenty years after the establishment of Massalia, the Phoenician cities in Sicily repelled an invasion of Dorian Greek settlers in Sicily while aiding the Elymians of Segesta against the Greek city of Selineus in 580 BC. The result was the defeated Greeks establishing themselves in Lipera, which became a pirate hub, a threat to all commerce (Greek included). Shortly after this event, Carthaginians under a "king" called Malchus warred successfully against the Libyan tribes in Africa, and then defeated the Greeks in Sicily, sending a part of the Sicilian booty to Tyre as tribute to Melquart. Malchus next moved to Sardinia, but suffered a severe defeat against the natives. He and his entire army were banished by the Carthaginian senate. They in turn returned to Africa and besieged Carthage, which duly surrendered. Malchus assumed power, but was later deposed and executed. The Carthaginian army, which up to this point had been a predominantly citizen militia, became one primarily made up of mercenaries.[74]

In the 530s there had been a three-sided naval struggle between the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Etrusco-Punic allies; the Greeks lost Corsica to the Etruscans and Sardinia to Carthage. Then the Etruscans attacked Greek colonies in the Campania south of Rome, but unsuccessfully. As an eventual result, Rome threw off their Etruscan kings of the Tarquin dynasty. Then the Roman Republic and Carthage in 509 entered into a treaty, which had the purpose of defining their respective commercial zones.[75][76]

The Greeks were energetic traders by sea,[77][78][79] who had been establishing emporia throughout the Mediterranean region in furtherance of their commercial interests. These parallel activities both by the Greeks and by Carthage led to persistent disputes over influence and control of commercial spheres, particularly in Sicily. When combined with the permanent foreign conquest of Phoenicia in the Levant, these Greek commercial challenges had caused many Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean to choose the leadership of Carthage. In 480 BC (concurrent with Persia's invasion of Greece), Mago's grandson Hamilcar landed a large army in Sicily in order to confront Syracuse (a colony of Corinth) on the island's eastern coast; yet the Greeks decisively prevailed at the Battle of Himera. A long struggle ensued, with intermittent warfare between Syracuse and Carthage. In 367 Hanno I the Great won a major naval victory over the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse, thereby blocking his attempt to take Punic Lilybaion in western Sicily.[80][81][82]

In 311 near Syracuse, Punic armies under another Hamilcar defeated the Greek tyrant Agathocles. Agathocles then attempted a bold strategy by putting his forces aboard ships, leaving Sicily, and landing his Greek army at Cape Bon, very near Carthage. The city became alarmed with palpable anxiety.[83] Yet Carthage again defeated Agathocles (310–307 BC). Thereafter the Greek world, preoccupied with its conquest of the Persian Empire in the east, lost interest in expanding its colonies in Sicily. Greek influence in the western Mediterranean became supplanted by Rome, the new rival of Carthage.[84][85][86]

During these centuries Carthage enlarged its commercial sphere, augmenting its markets along the African coast, in southern Iberia, and among the islands of the western Mediterranean, venturing south to develop rudiments of the Saharan trade, and exploring commercial opportunities in the Atlantic. Carthage also established its authority directly among the Numidian Berber peoples in the lands immediately surrounding the city, which grew more prosperous.[87][88][89]

Cyrene and Carthage

No records of any confrontations between the two powers are available, but a legend describes how the powers agreed on a border in Libya. Two pairs of champions set out for Carthage and Cyrene on the same day, each pair running towards the other city. When the runners met, the Carthaginian pair had covered more ground. Accused of cheating by the Greeks, they consented to be buried alive on the meeting spot, so that the territory between that spot and Carthage would become part of the Carthaginian domain. The Carthaginian champions were brothers, called Philaeni, and the border was marked by two pillars called the "Altars of the Philaeni". The African territorial boundary between the Western and Eastern Roman Empires was later set on this spot.[90]

Mago and the Magonids

Mago I, a general of the army, had assumed power in Carthage by 550 BC. Mago and his sons, Hasdrubal I and Hamilcar I, established the warlike tradition of Carthage by their successes in Africa, Sicily and Sardinia.[91] In 546 BC, Phocaeans fleeing from a Persian invasion established Alalia in Corsica (Greeks had settled there since 562 BC), and began preying on Etruscan and Punic commerce. Between 540 and 535 BC, a Carthaginian-Etruscan alliance had expelled the Greeks from Corsica after the Battle of Alalia. The Etruscans took control of Corsica, Carthage concentrated on Sardinia, ensuring that no Greek presence would be established in the island. The defeat also ended the westward expansion of Greeks for all time.

A war with Greek Massalia followed. Carthage lost battles but managed to safeguard Phoenician Iberia and close the Strait of Gibraltar to Greek shipping,[92] while Massalians retained their Iberian colonies in Eastern Iberia above Cape Nao.[93] Southern Iberia was closed to the Greeks. Carthaginians in support of the Phoenician colony Gades in Iberia,[94] also brought about the collapse of Tartessos in Iberia by 530 BC, either by armed conflict or by cutting off Greek trade. Carthage also besieged and took over Gades at this time. The Persians had taken over Cyrene by this time, and Carthage may have been spared a trial of arms against the Persian Empire when the Phoenicians refused to lend ships to Cambyses in 525 BC for an African expedition. Carthage may have paid tribute irregularly to the Great King. It is not known if Carthage had any role in the Battle of Cumae in 524 BC, after which Etruscan power began to wane in Italy.

Hasdrubal, the son of Mago, was elected as "king" eleven times, was granted a triumph four times (the only Carthaginian to receive this honour – there is no record of anyone else being given similar treatment by Carthage) and had died of his battle wounds received in Sardinia.[95] Carthage had engaged in a 25-year struggle in Sardinia, where the natives may have received aid from Sybaris, then the richest city in Magna Graecia and an ally of the Phocaeans. The Carthaginians faced resistance from Nora and Sulci in Sardinia, while Carales and Tharros had submitted willingly to Carthaginian rule.[96] Hasdrubal's war against the Libyans failed to stop the annual tribute payment.[97]

Carthaginians managed to defeat and drive away the colonization attempt near Leptis Magna in Libya by the Spartan prince Dorieus after a three-year war (514–511 BC).[98] Dorieus was later defeated and killed at Eryx in Sicily in 510 BC while attempting to establish a foothold in Western Sicily. Hamilcar, either the brother or nephew (son of Hanno)[99] of Hasdrubal, followed him to power in Carthage. Hamilcar had served with Hasdrubal in Sardinia and had managed to put down the revolt of Sardinians which had started in 509 BC.

Sicilian Wars

Defeat in the First Sicilian War had far reaching consequences, both political and economic, for Carthage. Politically, the old government of entrenched nobility was ousted, replaced by the Carthaginian Republic. A king was still elected, but the senate and the "Tribunal of 104" gained dominance in political matters, and the position of "suffet" became more influential. Economically, sea-borne trade with the Middle East was cut off by the mainland Greeks and Magna Graecia boycotted Carthaginian traders.[100] This led to the development of trade with the West and of caravan-borne trade with the East. Gisco, son of Hamilcar was exiled, and Carthage for the next 70 years made no recorded forays against the Greeks nor aided either the Elymians/Sicels or the Etruscans, then locked in struggle against the Greeks, or sent any aid to the Greek enemies of Syracuse, then the leading Greek city in Sicily. Based on this abstinence from Greek affairs, it is assumed that Carthage was crippled after the defeat of Himera.[101]

Focus was shifted on expansion in Africa and Sardinia, and on the exploration of Africa and Europe for new markets. The grandsons of Mago I, Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Sappho (sons of Hasdrubal), together with Hanno, Gisco and Himilco (sons of Hamilcar) are said to have played prominent parts in these activities,[102] but specific details of their roles are lacking. By 450 BC, Carthage had finally stopped paying tribute to the Libyans,[103] and a line of forts was built in Sardinia, securing Carthaginian control over the island coastline.

Hanno, son of Hamilcar may be the famous Hanno the Navigator,[104] which places his expedition around 460–425 BC, and Himilco may be the same as Himilco the Navigator,[105] which puts his expedition sometimes after 450 BC. Hanno the Navigator sailed down the African coast as far as Cameroon, and Himilco the Navigator explored the European Atlantic coast up to Britain in search of tin. These expeditions took place when Carthage was at the zenith of its power.[106] If Hanno and Himilco are indeed related to Mago, then Carthage had recovered quite rapidly from her "crippled" state. If Hanno and Himilco are not of the Magoniod family, then these expeditions may have taken place before 500 BC and Carthage might have been crippled for 70 years.

Carthage took no known part in the activities of the Sicilian chief Ducetius in Sicily against Syracuse, nor in the wars between Akragas and Syracuse, or the battles of the Etruscans against Syracuse and Cumae. Carthage's fleet also took no recorded part in the shattering defeat of the Etruscan fleet at the naval Battle of Cumae in 474 BC at the hands of the Greeks. She sat out the Peloponnesian War, refused to aid Segesta against Selinus in 415 BC and Athens against Syracuse in 413 BC. Nothing is known of any military activities Carthage might have taken in Africa or Iberia during this time. In 410 BC, Segesta, under attack from Selinus, appealed to Carthage again. The Carthaginian senate agreed to send help.

By 410 BC, Carthage had conquered much of modern-day Tunisia, strengthened and founded new colonies in Northwest Africa, and had sponsored a journey across the Sahara Desert, though in that year the Iberian colonies seceded, cutting off Carthage's major supply of silver and copper.

Second Sicilian War (410–404 BC)

"King" Hannibal Mago (son of Gisco and grandson of Hamilcar, who had died at Himera in 480 BC), led a small force to Sicily to aid Segesta, and defeated the army of Selinus in 410 BC. Hannibal Mago invaded Sicily with a larger force in 409 BC, landed at Motya and stormed Selinus (modern Selinunte); which fell before Syracuse could intervene effectively. Hannibal then attacked and destroyed Himera despite Syracusan intervention. Approximately 3,000 Greek prisoners were executed by Hannibal after the battle to avenge the death of Hamilcar at Himera, and the city was utterly destroyed. The Carthaginians did not attack Syracuse or Akragas, but departed for Africa with the spoils of war, and a three-year lull fell in Sicily.

Wars against Dionysius I

Dionysius I of Syracuse ruled for 38 years and engaged in four wars against Carthage with varying results. In retaliation for Greek raids on Punic Sicilian possessions in 406 BC, Hannibal Mago led a second Carthaginian expedition, perhaps aiming to subjugate all Sicily. Carthaginians first moved against Akragas, during the siege of which the Carthaginian forces were ravaged by plague, Hannibal Mago himself succumbing to it. His kinsman and successor, Himilco (the son of Hanno[107]), successfully captured Akragas, then captured the cities of Gela and Camarina while repeatedly defeating the army of Dionysius, the new tyrant of Syracuse, in battle. Himilco ultimately concluded a treaty with Dionysius (an outbreak of plague may have caused this), which allowed the Greek settlers to return to Selinus, Akragas, Camarina and Gela, but these were made tributary to Carthage. The Elymian and Sicel cities were kept free of both Punic and Greek dominion, and Dionysius, who had usurped power in Syracuse, was confirmed as tyrant of Syracuse. The home-bound Punic army carried the plague back to Carthage.

In 398 BC, after building up the power of Syracuse while Carthage was suffering from the plague, Dionysius broke the peace treaty. His soldiers massacred the Carthaginian traders in Syracuse, and Dionysius then besieged, captured and destroyed the Carthaginian city of Motya in Western Sicily while foiling the relief effort of Himilco through a brilliant stratagem. Himilco, who had been elected "king", responded decisively the following year, leading an expedition which not only reclaimed Motya, but also captured Messina. Finally, he laid siege to Syracuse itself after Mago, his kinsman, crushed the Greek fleet off Catana. The siege met with great success throughout 397 BC, but in 396 BC plague ravaged the Carthaginian forces, and they collapsed under Syracusan attack. Himilco paid an indemnity of 300 talents for safe passage of Carthaginian citizens to Dionysius. He abandoned his mercenaries and sailed to Carthage, only to commit suicide after publicly assuming full responsibility for the debacle. After his death, the power of "kings" would be severely curtailed, and the power of the oligarchy, ruling through the "Council of Elders" and the newly created "Tribunal of 104", correspondingly increased.[108]

The plague, brought back from Sicily, ravaged Carthage and a severe rebellion in Africa occurred at the same time. Carthage was besieged and her naval power was crucial in supplying the city. Himilco was succeeded by his kinsman Mago, who was occupied with subduing the rebellion while Dionysius consolidated his power in Sicily. The next clash against Carthage took place during 393 BC. Mago, in an attempt to aid the Sicels under attack from Syracuse, was defeated by Dionysius. Carthage reinforced Mago in 392 BC, but before he could engage the forces of Dionysius the Sicels had switched sides. The Carthaginian army was outmanoeuvred by Dionysius, and peace soon followed, which allowed Carthage to retain her domain in Sicily while allowing Syracuse a free hand against the Sicels. The treaty lasted nine years.

Dionysius began the next war in 383 BC, but details of the first four years of clashes are unavailable. Carthage sent a force under Mago to Southern Italy for the first time to aid Italian Greeks against Syracuse in 379 BC. The expedition met with success, but during the same year, Libyans and Sardinians revolted, and a plague again swept through Africa. The stalemate in Sicily was broken when Dionysius defeated and killed Mago at the battle of Cabala in 378 BC (Mago was the last "suffet" to lead troops personally in battle. The Magonid dynasty ended with the death of his son Himilco).

Carthage initiated peace negotiations, which dragged for a year but ultimately faltered. Dionysius had consolidated his gains during the lull, and attacked Punic Sicily. He was decisively defeated in the battle of Cronium in 376 BC by Himilco, the son of Mago. Carthage did not follow up the victory but settled for an indemnity payment of 1000 talents and restoration of Carthaginian holdings in Sicily.[109] Nothing is known of how or when Carthage subdued the African and Sardinian rebellion.

Dionysius initiated hostilities again in 368 BC, and after initial successes besieged Lilybaeum, but the defeat of his fleet at Drepanum led to a stalemate and the war ended with his death in 367 BC. Carthaginian holdings west of the Halycas river remained secure.

Other fourth century actions

Hanno, a wealthy aristocrat, was in command in Sicily, and he and his family played a leading role in the politics of Carthage for the next fifty years. Carthage had entered into an alliance with the Etruscans, while Tarentum and Syracuse concluded a similar treaty. A power struggle saw Hanno eventually depose his rival Suniatus (Leader of the Council of Elders) through the judicial process and execute him.[110] With Sicily secure, Carthage launched campaigns in Libya, Spain and Mauretania, which eventually earned Hanno the title "Magnus",[111] along with great wealth, while Hamilcar and Gisco, his sons, served with distinction in the campaigns. However, Hanno aimed to obtain total power and planned to overthrow the "Council of Elders". His scheme failed, leading to his execution along with Hamilcar and most of his family. Gisco was exiled.[112]

Carthage and Rome (by now a significant power in Central Italy), concluded a second treaty in 348 BC.[113] Romans were allowed to trade in Sicily, but not to settle there, and Iberia, Sardinia and Libya were forbidden to Roman exploration, trade and settlement activities. Romans were to hand over any settlements they captured there to Carthage. Carthaginians pledged to be friendly with the Latins, to return to Rome cities captured in Latium, and not to spend the night in Roman territory under arms. This shows that the Iberian Phoenician colonies were in the Carthaginian sphere of influence by 348 BC.

The death of Dionysius ultimately led to a power struggle between Dion, Dionysius II of Syracuse and other aspirants. The Punic holdings in Sicily were secure as Syracuse had begun to lose its hegemony over other Sicilian cities because of internal political conflict that turned to open warfare. Carthage had done little directly during 366–346 BC to interfere, but in 343 BC decided to oppose Timoleon. Carthaginian army and fleet activity failed to stop his assumption of power in Syracuse. Mago, the Carthaginian commander, had the advantage of numbers, the support of allied Greeks, and was even admitted into Syracuse. But he bungled so much that he killed himself instead of facing the tribunal of 104 after returning to Carthage.

Timoleon managed to gain support of the tyrants in league with Carthage, and the Punic expedition sent to Sicily in retaliation of Syracusan raids was crushed in the Battle of the Crimissus in 341 BC by the combined Greek force. Gisco, the son of Hanno "Magnus" was recalled and elected as "king", but he achieved little and after Timoleon had captured some pro-Carthaginian Greek cities, a peace treaty was concluded in 338 BC. The accord left the Punic possessions in Sicily unchanged,[114] with Syracuse free to deal with other cities in Sicily.

While Carthage was engaged in Sicily, the rise of Macedon under Philip II and Alexander the Great saw the defeat of Greek city-states and the fall of the Achaemenid Empire. All the mainland Phoenician cities had submitted to Alexander except Tyre, which was besieged and sacked in 332 BC, though the Carthaginian citizens present in the city were spared. Carthage sent two delegations to Alexander, one in 332 BC and another in 323 BC, but little was achieved. Alexander was raising a fleet in Cilicia for the invasion of Carthage, Italy and Iberia when he died, sparing Carthage an ordeal. Battles among the Diadochi and the ultimate three-way struggle among Antigonid Macedon, Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria spared Carthage any further clashes with the successor states for some time. Trade relations were opened with Egypt, giving Carthage sea-borne access to the Eastern markets, which had been cut off since 480 BC.

Third Sicilian War (315–307 BC)

In 315 BC, Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse, seized the city of Messene (present-day Messina). In 311 BC, he invaded the Carthaginian holdings on Sicily, breaking the terms of the current peace treaty, and laid siege to Akragas. Hamilcar, grandson of Hanno "Magnus",[115] led the Carthaginian response and met with tremendous success. By 310 BC, he controlled almost all of Sicily and besieged Syracuse itself.

In desperation, Agathocles secretly led an expedition of 14,000 men to the mainland, hoping to save his rule by leading a counterstrike against Carthage itself. The expedition ravaged Carthaginian possessions in Africa. Troops recalled from Sicily under the joint command of Hanno and Bomilcar (two political rivals) were defeated by Agathocles, Hanno himself falling in battle. Ophellas came from Cyrene with 10,000 troops to aid the Syracusans. Agathocles eventually murdered Ophellas and took over his army. Although the Greeks eventually managed to capture Utica, Carthage continued to resist, and Syracuse remained blockaded.

In Sicily, Hamilcar led a night attack on Syracuse, which failed, leading to his capture and subsequent execution by the Syracusans. Agathocles returned to Syracuse in 308 BC and defeated the Punic army, thus lifting the blockade, then returned to Africa. In 307, the war came to an end when Carthage finally managed to defeat the Greeks in Africa, after surviving a coup attempt by Bomilcar. Agathocles abandoned his army and returned to Syracuse, where a treaty divided Sicily between Punic and Greek domains.

Pyrrhic War

Between 280 and 275 BC, Pyrrhus of Epirus waged two major campaigns in an effort to protect and extend the influence of the Molossians in the western Mediterranean: one against the emerging power of the Roman Republic in southern Italy, the other against Carthage in Sicily. The Greek city of Tarentum had attacked and sacked the city of Thurii and expelled the newly installed Roman garrison in 282 BC. Committed to war, they appealed to Pyrrhus, who ultimately arrived with an army and defeated the Romans in the Battle of Heraclea and the Battle of Asculum. In the midst of Pyrrhus' Italian campaigns, he received envoys from the Sicilian cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse, and Leontini, asking for military aid to remove the Carthaginian dominance over that island.[116] Carthage had attacked Syracuse and besieged the city after seizing Akragas. Mago, the Carthaginian admiral, had 100 ships blockading the city. Pyrrhus agreed to intervene, and sailed for Sicily. Mago lifted the siege and Pyrrhus fortified the Sicilian cities with an army of 20,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 20 war elephants, supported by some 200 ships. Initially, Pyrrhus' Sicilian campaign against Carthage was a success, pushing back the Carthaginian forces, and capturing the city-fortress of Erice; though he was not able to capture Lilybaeum.[117] After a two-month siege, Pyrrhus withdrew.

Following these losses, Carthage sued for peace, but Pyrrhus refused unless Carthage was willing to renounce its claims on Sicily entirely. According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus set his sights on conquering Carthage itself, and to this end, began outfitting an expedition. The Carthaginians fought a battle outside Lilybaeum in 276 BC, and lost. The ruthless treatment of the Sicilian cities in his preparations for this expedition, and the execution of two Sicilian rulers whom Pyrrhus claimed were plotting against him, led to such a rise in animosity towards the Greeks that Pyrrhus withdrew from Sicily and returned to deal with events occurring in southern Italy.[118] The fleet of Pyrrhus was defeated by Carthage, the Greeks losing 70 ships in the battle. Pyrrhus' campaigns in Italy were futile, and Pyrrhus eventually withdrew to Epirus. For Carthage, this meant a return to the status quo. For Rome, however, the failure of Pyrrhus to defend the colonies of Magna Graecia meant that Rome absorbed them into its sphere of influence, bringing it closer to complete domination of the Italian peninsula. Rome's domination of Italy, and proof that Rome could pit its military strength successfully against major international powers, would pave the way to the future Rome–Carthage conflicts of the Punic Wars.

Conflict with Rome

In 509 BC, a treaty was signed between Carthage and Rome indicating a division of influence and commercial activities. This is the first known source indicating that Carthage had gained control over Sicily and Sardinia, as well as Emporia and the area south of Cape Bon in Africa. Carthage may have signed the treaty with Rome, then an insignificant backwater, because Romans had treaties with the Phocaeans and Cumae, who were aiding the Roman struggle against the Etruscans at that time. Carthage had similar treaties with Etruscan, Punic and Greek cities in Sicily. By the end of the 6th century BC, Carthage had conquered most of the old Phoenician colonies e.g. Hadrumetum, Utica and Kerkouane, subjugated some of the Libyan tribes, and had taken control of parts of the Northwest African coast from modern Morocco to the borders of Cyrenaica. It was also fighting wars in defence of Punic colonies and commerce. However, only the details of her struggle against the Greeks have survived – which often makes Carthage seem "obsessed with Sicily".

Punic Wars

First Punic War

The emergence of the Roman Republic led to sustained rivalry with the more anciently established Carthage for dominion of the western Mediterranean. As early as 509 BC. Carthage and Rome had entered into treaty status, chiefly regarding trading areas; later in 348, another similar treaty was made between Carthage, Tyre, Utica, and Rome; a third Romano-Punic treaty in 280 regarded wars against the Greek invader Pyrrhus.[119][120][121] Yet eventually their opposing interests led to disagreement, suspicion, and conflict.

The island of Sicily, lying at Carthage's doorstep, became the arena in which this conflict played out. From their earliest days, both the Greeks and Phoenicians had been attracted to the large island, establishing a large number of colonies and trading posts along its coasts. Small battles had been fought between these settlements for centuries. Carthage had to contend with at least three Greek incursions, in 580 BC, in 510 BC, and a war in which the city of Heraclea was destroyed. Gelo had fought in the last war and had secured terms for the Greeks.

The Punic domain in Sicily by 500 BC contained the cities of Motya, Panormus and Soluntum. By 490 BC, Carthage had concluded treaties with the Greek cities of Selinus, Himera, and Zankle in Sicily. Gelo, the tyrant of Greek Syracuse, backed in part by support from other Greek city-states, had been attempting to unite the island under his rule since 485 BC. When Theron of Akragas, father-in-law of Gelo, deposed the tyrant of Himera in 483 BC, Carthage decided to intervene at the instigation of the tyrant of Rhegion, who was the father-in-law of the deposed tyrant of Himera.

Hamilcar prepared the largest Punic overseas expedition to date and, after three years of preparations, sailed for Sicily. This enterprise coincided with the expedition of Xerxes against mainland Greece in 480 BC, prompting speculations about a possible alliance between Carthage and Persia against the Greeks, although no documentary evidence of this exists. The Punic fleet was battered by storms en route, and the Punic army was destroyed and Hamilcar killed in the Battle of Himera by the combined armies of Himera, Akragas and Syracuse under Gelo. Carthage made peace with the Greeks and paid a large indemnity of 2000 silver talents, but lost no territory in Sicily.

When Agathocles died in 288 BC, a large company of Italian mercenaries who had previously been held in his service found themselves suddenly without employment. Rather than leave Sicily, they seized the city of Messana. Naming themselves Mamertines (or "sons of Mars"), they became a law unto themselves, terrorizing the surrounding countryside.

The Mamertines became a growing threat to Carthage and Syracuse alike. In 265 BC, Hiero II, former general of Pyrrhus and the new tyrant of Syracuse, took action against them. Faced with a vastly superior force, the Mamertines divided into two factions, one advocating surrender to Carthage, the other preferring to seek aid from Rome. As a result, embassies were sent to both cities.

While the Roman Senate debated the best course of action, the Carthaginians eagerly agreed to send a garrison to Messana. A Carthaginian garrison was admitted to the city, and a Carthaginian fleet sailed into the Messanan harbour. However, soon afterwards they began negotiating with Hiero. Alarmed, the Mamertines sent another embassy to Rome asking them to expel the Carthaginians.

Hiero's intervention had placed Carthage's military forces directly across the narrow channel of water that separated Sicily from Italy. Moreover, the presence of the Carthaginian fleet gave them effective control over this channel, the Strait of Messina, and demonstrated a clear and present danger to nearby Rome and her interests. The Roman senate was unable to decide on a course of action and referred the matter to the people, who voted to intervene.

The Roman attack on the Carthaginian forces at Messana triggered the first of the Punic Wars. Over the course of the next century, these three major conflicts between Rome and Carthage would determine the course of Western civilization. The wars included a Carthaginian invasion led by Hannibal, which nearly prevented the rise of the Roman Empire. Eventual victory by Rome was a turning point which meant that the civilization of the ancient Mediterranean would pass to the modern world via Southern Europe instead of Northwest Africa.

"[P]robably both sides miscalculated the reaction of the other. The war... escalated beyond anyone's expectations... . [B]egun over one town in [Sicily] [it] became a struggle for the whole island."[122] The conflict developed into a naval war in which the Romans learned how to fight at sea and then decisively defeated the Punic fleet. Carthage lost Sicily (all of its former western portion) and paid a huge indemnity. Evidently Carthage had not then been ready to wage war against an equal power.[123][124]

Following the defeat of Carthage, their mercenaries revolted against them, which threatened the survival of the Punic social order. Yet Carthage endured, under their opposing leaders Hanno II the Great, and Hamilcar Barca. During this crisis at Carthage, Rome refused to aid the rebels (underpaid mercenaries and dissident Berbers), but later occupied Sardinia.[125][126]

Second Punic War

As to the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), the ancient Greek historian Polybius gives three causes: the anger of Hamilcar Barca (father of Hannibal) whose army in Sicily the Romans did not defeat in the first war; the Roman seizure of Sardinia during the mercenary revolt; and, creation by the Barcid military family of a new Punic power base in Hispania.[127][128][129][130] Nonetheless, the immediate cause was a dispute concerning Saguntum (near modern Valencia) in Hispania. After prevailing there, Hannibal Barca set out northward, eventually leading his armies over the Alps into Italy.[131][132]

At first Hannibal ("grace of Baal") won great military victories against Rome on its own territory, at Trasimeno (217 BC), and at Cannae (216 BC), which came close to destroying Rome's ability to wage war. But the majority of Rome's Italian allies remained loyal; Rome drew on all her resources and managed to rebuild her military strength. For many years Hannibal enjoyed the support of those cities who defected from Rome, including Capua south of Rome and Tarentum in the far south; Hannibal remained on campaign there, maintaining his army and posing an existential threat to Rome and her remaining Italian allies. Yet the passage of years appeared to forestall Hannibal's chances, although for a while Rome's fate appeared to hang in the balance.[133]

Meanwhile, Hispania remained throughout the year 211 BC the domain of armies under Hannibal's two brothers: Hasdrubal and Mago, and also the Punic leader Hasdrubal Gisco. Yet Roman forces soon began to contest Carthage for its control. In 207 BC an overland attempt by his brother Hasdrubal to reinforce Hannibal in Italy failed. Rome became encouraged. By 206, the fortunes of war in Hispania had turned against Carthage; the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio (later Africanus, 236–183 BC) had decisively defeated Punic power in the peninsula.[134]

In 204 Roman armies under Scipio landed at Utica near Carthage, which forced Hannibal's return to Africa. One Numidian king, Syphax, supported Carthage; however, Syphax met an early defeat. Rome found an old ally in another Berber king of Numidia, the scrambling Masinissa, who would soon grow in power and fame. Decisively, he chose to fight with Rome against Carthage. At the Battle of Zama in 202 BC the Roman general Scipio Africanus, with Masinissa commanding Numidian cavalry on his right wing, defeated Hannibal Barca, ending the long war.[135][136][137] Carthage lost all of its trading cities and silver mines in Hispania, and its other possessions in the western Mediterranean; also lost: Carthage's political influence over the Berber Kingdoms (Numidia and Mauretania), which became independent Roman allies. Masinissa, traditional king of the Numidian Massyli, was restored to an enlarged realm. Carthage, reduced to its immediate surroundings, its actions restricted by treaty, was required to pay a very large indemnity to Rome over fifty years.[138][139][140][141]

Yet Carthage soon revived under the reforms initiated by Hannibal and, free of defence burdens, prospered as never before. In 191 Carthage offered to pay off early the indemnity due Rome, causing alarm in the anti-Punic faction there. Then the corrupt and rigid oligarchy in Carthage joined with this Roman faction to terminate Hannibal's reforms; eventually Hannibal was forced to flee the city. Many Romans continued to nurse a hot, across-the-board opposition to Carthage.[142] The anti-Punic faction was led by the politician Cato (234–149 BC) who, before the last Punic war, at every occasion in the Senate at Rome had proclaimed, Carthago delenda est! "Carthage must be blotted out!".[143][144]

Yet the Roman military hero of the Second Punic War, Scipio Africanus (236–183 BC) favoured a generous policy toward Hannibal. Later Scipio's son-in-law Scipio Nasica (183–132 BC) supported the cause of Carthage.[145] Indeed, the pro-Hellenic Scipio circle at Rome, which included Scipio Aemilianus (185–129 BC) and Polybius (203–120 BC) the Greek historian, welcomed and embraced the Berber Publius Terentius Afer (195–159 BC). Terence was born in Carthage yet in Rome he had mastered the Latin language well and became a celebrated Roman playwright.[146][147][148] Also the Roman comedy entitled Poenulus ("The Carthaginian") of circa 190 BC by the popular dramatist Plautus (c. 250–184 BC) had featured an extended family from Carthage who in Greece triumphed over the nefarious schemes of a leno, a Roman slaver.[149][150]

There were likewise citizens of Carthage who increasingly accepted the cultural influence of the Hellenic world. For example, Hasdrubal, a son of Carthage (also known as Cleitomachus) became a student of Greek philosophy and travelled to join the Platonic Academy at Athens. Several decades later Hasdrubal himself became its leader, the scholarch (129–110 BC).[151] Hasdrubal may be said to have followed in the footsteps of a Phoenician trader from Cyprus, Zeno of Citium (335–265 BC), who earlier in Athens had founded another, the Stoic, school of philosophy.[152] Despite the above Roman peace faction and such multiple, cultural and artistic interactions between Rome and Carthage within the context of the Mediterranean world, again war came.

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) began following armed conflict between Carthage and the Numidian king Masinissa (r.204–148 BC), who for decades had been attacking and provoking the city. Carthage eventually responded, yet by prosecuting this defensive war the city had broken its treaty with Rome. Hence, when challenged by Rome, Carthage surrendered to Rome's superior strength. The war faction in control at Rome, however, was determined to undo Carthage; cleverly hiding its true aims while talks proceeded (wherein Carthage gave up significant military resources), Rome eventually presented Carthage with an ultimatum: either evacuate the city which would then be destroyed; or war. Roman armies landed in Africa and began to lay siege to the magnificent city of Carthage, which rejected further negotiations. The end came: Carthage was destroyed; its surviving citizens enslaved.[153][154][155]

In the aftermath, the region (much of modern Tunisia) was annexed by the Roman Republic as the new Province of Africa. The city of Carthage was eventually rebuilt by the Romans under Julius Caesar, beginning in 46 BC. It later became capital of Africa Province and a leading city of the Empire. The entire province, Berber and Punic with a large Latin and multinational influx, then experienced a centuries-long renaissance. Long after the fall of Rome, the re-built city of Carthage would be again undone.[156]

Fall of Carthage

The fall of Carthage was at the end of the third Punic War in 146 BC. In spite of the initial devastating Roman naval losses at the beginning of the series of conflicts and Rome's recovery from the brink of defeat after the terror of a 15-year occupation of much of Italy by Hannibal, the end of the series of wars resulted in the end of Carthaginian power and the complete destruction of the city by Scipio Aemilianus. The Romans pulled the Phoenician warships out into the harbour and burned them before the city, and went from house to house, slaughtering and enslaving the people. The city was set ablaze, and in this way was razed with only ruins and rubble to field the aftermath.

Roman Carthage

Since the 19th century, some historians have written that the city of Carthage was salted to ensure that no crops could be grown there, but there is no ancient evidence for this.[157]

When Carthage fell, its nearby rival Utica, a Roman ally, was made capital of the region and replaced Carthage as the leading centre of Punic trade and leadership. It had the advantageous position of being situated on the Lake of Tunis and the outlet of the Medjerda River, Tunisia's only river that flowed all year long. However, the prestige of the site of Carthage was such that first Caesar, and then Augustus, decided to rebuild it as a Roman city and the capital of Roman Africa.

A new city of Carthage was built on the same land, and by the 1st century AD it had grown to the second largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire, with a peak population of 500,000. It was the centre of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major "breadbasket" of the empire. Carthage briefly became the capital of a usurper, Domitius Alexander, in 308–311 AD.

Carthage also became a centre of early Christianity. Tertullian rhetorically addressed the Roman governor with the fact that the Christians of Carthage that just yesterday were few in number, now "have filled every place among you —cities, islands, fortresses, towns, market-places, the very camp, tribes, companies, palaces, senate, forum; we have left nothing to you but the temples of your gods." (Apologeticus written at Carthage, c. 197).

In the first of a string of rather poorly reported Councils of Carthage a few years later, no fewer than 70 bishops attended. Tertullian later broke with the mainstream that was represented more and more by the bishop of Rome, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, which Augustine of Hippo spent much time and parchment arguing against. In 397 at the Council of Carthage, the Biblical canon for the Western Church was confirmed.

The Vandals under their king Genseric crossed to Africa in 429,[158] either as a request of Bonifacius, a Roman general and the governor of the Diocese of Africa,[159] or as migrants in search of safety. They subsequently fought against the Roman forces there and by 435 had defeated the Roman forces in Africa and established the Vandal Kingdom. After a failed attempt to recapture the city in the 5th century, the Byzantines finally subdued the Vandals in the 6th century. Using Gaiseric's grandson's disposal by a distant cousin, Gelimer, as either a valid justification or pretext, the Byzantines dispatched an army to conquer the Vandal kingdom. On Sunday, 15 October 533, the Byzantine general Belisarius, accompanied by his wife Antonina, made his formal entry into Carthage, sparing it a sack and a massacre.

During the emperor Maurice's reign, Carthage was made into an Exarchate, as was Ravenna in Italy. These two exarchates were the western bulwarks of Byzantium, all that remained of its power in the west. In the early 7th century, it was the Exarch of Carthage Heraclius, who overthrew Emperor Phocas.

The Byzantine Exarchate was not, however, able to withstand the Arab conquerors of the 7th century. The first Arab assault on the Exarchate of Carthage was initiated from Egypt without much success in 647. A more protracted campaign lasted from 670 to 683. In 698, the Exarchate of Africa was finally overrun by Hassan Ibn al Numan and a force of 40,000 men. The population was displaced to the neighbouring town of Tunis which in turn vastly eclipsed Carthage as the major regional centre. Carthage's materials were used to supply the expansion of Tunis.[160] The destruction of the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to the Byzantine Empire's influence in the region.

Modern Carthage

The modern Carthage is a suburb of Tunis, the capital city of Tunisia, situated at the site of the ancient capital of the Carthaginian empire. Carthage was little more than an agricultural village for nine hundred years until the middle of the 20th century; since then it has grown rapidly as an upscale coastal suburb.[161][162] In 2004 it had a population of 15,922 according to the national census,[163] and an estimated population of 21,276 in January 2013.[164]

In February 1985, Ugo Vetere, the mayor of Rome, and Chedly Klibi, the mayor of Carthage, signed a symbolic treaty "officially" ending the conflict between their cities, which had been supposedly extended by the lack of a peace treaty for more than 2,100 years.[165] Carthage is a tourist attraction. The Carthage Palace (the Tunisian presidential palace), is located in the city.[166]

The modern Carthage, beyond its residential vocation, seems to be invested with an affirmed political role. The geographical configuration of Carthage as an old peninsula save Carthage from Tunis' inconveniences and embarrassments and increase its attractiveness as a place of residence for the elites.[167] If Carthage is not the capital, it tends to be the political pole, a "place of emblematic power," according to Sophie Bessis,[168] leaving to Tunis the economic and administrative roles.

Sources

Some ancient translations of Punic texts into Greek and Latin as well as inscriptions on monuments and buildings discovered in Northwest Africa survive.[169] However, the majority of available primary source material about Carthaginian civilization was written by Greek and Roman historians, such as Livy, Polybius, Appian, Cornelius Nepos, Silius Italicus, Plutarch, Dio Cassius and Herodotus. These authors came from cultures nearly always in competition and often in conflict, with Carthage. The Greeks contested with Carthage for Sicily,[170] and the Romans fought the Punic Wars against Carthage.[171] Inevitably, the accounts of Carthage written by outsiders include significant bias. Recent excavation of ancient Carthaginian sites has brought much more primary material to light. Some of the finds contradict or confirm aspects of the traditional picture of Carthage, but much of the material is still ambiguous.

References

- C. Edmund Bosworth (2008). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Brill Academic Press. p. 436. ISBN 978-9004153882.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- SorenKhader 1991, p. 90.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2 November 2007). "Mogador". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Gilbert and Colette Picard, Vie et Mort de Carthage (Paris: Hachett 1968), translated as The Life and Death of Carthage (New York: Taplinger 1969), at 30.

- Serge Lancel (1995). Carthage. Translated by Antonia Nevill. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 20–23.

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) at 28–35.

- Philip K. Hitti, History of Syria. Including Lebanon and Palestine (New York: Macmillan 1951) at 102 n.4.

- I Kings 10:22.

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1969) at 16–17, where Tarshish might refer to a cargo, a ship, or a place. Tarshish ships sailed over the Red Sea to Ophir, as well as across the Mediterranean to Tartessus in Hispania.

- Raphael Patai, The Children of Noah. Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times (Princeton Univ. 1998) at 12–13, 40, 134. At 133 Patai notes the Jewish reliance on Phoenician shipwrights and craft in building and managing the ships, citing I Kings 22:49, as well as the biblical moral critique in II Chronicles 20:35–37.

- More on the Punic Tarshish trade as found in the Bible: here at end of this section, i.e., Ezekiel 27.

- The Wadi Majardah was also known to the ancient classical world as the river Bagradas. E.g., Appian, The Civil Wars, II, 44, as translated (Penguin Books 1996) at 92.

- Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 17–19. The ruins of Utica, within the modern Republic of Tunisia and now situated 10 km inland, have been excavated to some extent, especially regarding a cemetery dating to the 8th century B.C.E. No conclusive earlier finds have been identified, but the ruins were very disturbed before its trained excavation and much work remains to be done.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at 69.

- Warmington, Carthage (1960, 1964) at .

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1969) at 18, and at 27: 30 km being "a good day's sailing".

- Etymologically Dido comes from the same Semitic root as does David which means "beloved". Elissa (Greek version; from Phoenician Elishat) is the feminine form of the remote Phoenician creator god El, also a name for the God of the Hebrews. Smith, Carthage and the Carthaginians (1878, 1902) at 13.

- Probably Dido is an epithet from the Semitic root dod, "love". Barton, Semitic and Hamitic Origins (1934) at 305.

- But cf., Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 23–24, 35–36.

- E.g., I Kings chapters 16, 18, 21, and II Kings chapter 9. Some place Jezebel's origin at Sidon, a Phoenician city-state and major rival to Tyre; more likely at that time Tyre and Sidon were united.

- Donald Harden, The Phoenicians (New York: Frederick A. Praeger 1962) at 52, 66. Harden at 53 gives a schema of the "Royal Houses of Tyre, Israel, and Judah in the 9th century B.C." Jezebel was mother of kings both in Israel and in Judah. Jezebel's daughter Athaliah wed the King of Judah, where Athaliah later became queen.

- Jezebel, as wife of King Ahab of Israel, orchestrated sinister plots from her position at court. Her daughter Athaliah when Queen of Judah (r. 842–836) also involved herself in murderous court intrigue leading to her death. Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdman's Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1987) at 580–581 (Jezebel), 28–29 (Ahab), 30–31 (Ahaziah, King of Israel, son of Jezebel and Ahab), 559–560 (Jehoram, King of Israel, son of Jezebel and Ahab); 560 (Jehoram, King of Judah, husband of Athaliah), 103–104 (Athaliah, Queen of Judah, daughter of Jezebel and Ahab), 31 (Ahaziah, King of Judah, son of Jehoram and Athaliah).

- Jezebel might be compared to Bathsheba, whose adulterous affair with King David (r., c. 1010–970) led to the covert murder of her soldier husband. Later on, she apparently connived in the execution of Adonijah, a rival to her son Solomon. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Harvard Univ. 1973) at 227 (Uriah), 237 (Adonijah). Yet the Hebrew Bible condemns Jezebel (who killed Hebrew prophets) but not Bathsheba (whose adultery was a youthful affair, and whose latter alleged offense is subject to different interpretations).

- Intrigue and palace revolts were then common to the royal courts of Phoenicia, Judah and Israel. Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 24. Historically, of course, similar criminality by royals is reported in many nations.

- Pygmilion is a Greek form of a Phoenician name, which was perhaps Pumai-jaton. Stéphane Gsell, Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord, volume 1 (Paris: Librairie Hachette 1921) at 391.

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus at XVIII,5.

- David Soren, Aicha Ben Abed Ben Khader, Hedi Slim, Carthage. Uncovering the Mysteries and Splendors of Ancient Tunisia (New York: Simon & Schuster 1990) at 23–24 (Dido's escape from Tyre), 17–29 (Dido), 23–25 (Trogus). Trogus appears to be following the events as recorded by the historian Timaeus (c. 300) of Sicily, whose works are largely lost. Much of the writings of Trogus himself are lost, but its abbreviated content survives in an ancient summary by Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus. Dates for Justin are approximate: the 2nd–4th centuries.

- Harden, The Phoenicians (1962) at 66–67.

- The captured temple women of Cyprus are possibly symbolic or a metaphor, parallel to the rape of the Sabine women in Roman lore, notes Lancel in his Carthage (1992, 1995) at 34.

- Lancel, Carthage (1992, 1995) at 38, reads in Justin's Epitome the tribe Maxitani, per the Punic district pagus Muxi, instead of interpreting it as a corrupt form of the tribe Mauri or the Mauritani.

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus at XVIII,6.

- Picard, Life and Death of Carthage (1968, 1969) re Dido at 31, 47, 154.

- The celebration of Dido thereafter demonstrates the Carthaginian's abiding respect for committed dedication to an all-encompassing purpose, even to taking the ultimate step of self-sacrifice. Cf., Soren, Khader, Slim, Carthage (1990) at 28.

- Virgil, Aeneid, as translated by Fitzgerald (New York: Vintage 1990). In the Aeneid Virgil attempted, in part, to personify Carthage and Rome, and mythically explain their subsequent antagonism. The story line follows Aeneas as he escapes from his city of Troy after its capture by the Greeks. Eventually, following adventures he arrives (as steered by the gods) in Italy where he acts in the foundation of Rome. In the meantime, during the course of his journeys, he landed at Carthage where the Queen Dido and Aeneas became lovers.

- The Queen bought as much land as an ox hide would cover, then cut it at the edge round and round into a very thin, long strip, enough to surround the citadel area. For the Romans this exemplified Berber simplicity and Phoenician sophistry. Lancel, Serge (1992). Carthage. pp. 23–25.

- Reference to Dido's purchase of the Byrsa: Virgil, Aeneid (Vintage 1990) at 16, lines 501–503 (I, 367–368).

- Appian (circa 95–165), Romaiken Istorian Roman History, at Book VIII: chap. 1, sec. 1.

- Virgil, Aeneid (Vintage 1990). The god Jupiter compels the hero Aeneas to leave Dido and travel to his destiny at Rome (at pages 103–105, lines 299–324, 352–402 [[IV, {220s-230s, 260s-290s}]]). The Queen Dido then dies by her own hand and is consumed in a sacrificial fire (at 119–120, lines 903–934 [[IV, {650s-670s}]]). Later, Aeneas meets Dido in the underworld (at 175–176, lines 606–639 [[VI, {450s-470s}]]).