Honolulu

Honolulu (/ˌhɒnəˈluːluː/;[7] Hawaiian: [honoˈlulu]) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is located in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island of Oʻahu,[lower-alpha 1] and is the westernmost and southernmost major U.S. city. Honolulu is Hawaii's main gateway to the world. It is also a major hub for business, finance, hospitality, and military defense in both the state and Oceania. The city is characterized by a mix of various Asian, Western, and Pacific cultures, as reflected in its diverse demography, cuisine, and traditions.

Honolulu, Hawaii | |

|---|---|

State capital city | |

| City and County of Honolulu | |

Clockwise from top: Downtown, Pearl Harbor, statue of King Kamehameha I in front of Aliʻiolani Hale downtown, Diamond Head, waterfront on Waikīkī Beach and Honolulu Hale (City Hall) | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Crossroads of the Pacific, Sheltered Bay, HNL, The Big Pineapple, Paradise | |

| Motto(s): | |

Interactive map of Honolulu | |

| Coordinates: 21°18′25″N 157°51′30″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Hawaii |

| County | Honolulu |

| Incorporated | April 30, 1907[2] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rick Blangiardi (I) |

| • Council | Members |

| Area | |

| • City | 68.4 sq mi (177.2 km2) |

| • Land | 60.5 sq mi (156.7 km2) |

| • Water | 7.9 sq mi (20.5 km2) |

| • Urban | 170.2 sq mi (440.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 19 ft (6 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 343,302 (55th) |

| • Density | 5,791/sq mi (2,236.1/km2) |

| • Urban | 802,459 |

| • Urban density | 4,702/sq mi (1,815.4/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,016,508[5] |

| Demonym | Honolulan |

| Time zone | UTC−10:00 (Hawaiian (HST)) |

| ZIP Codes | 96801–96850 |

| Area code | 808 |

| FIPS code | 15-17000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 366212[6] |

| Website | www |

Honolulu means "sheltered harbor"[9] or "calm port" in Hawaiian;[10] its old name, Kou, roughly encompasses the area from Nuʻuanu Avenue to Alakea Street and from Hotel Street to Queen Street, which is the heart of the present downtown district.[11] The city's desirability as a port accounts for its historical growth and importance in the Hawaiian archipelago and the broader Pacific region. Honolulu has been the capital of the Hawaiian Islands since 1845, first of the independent Hawaiian Kingdom, and after 1898 of the U.S. territory and state of Hawaii. The city gained worldwide recognition following Japan's attack on nearby Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, which prompted decisive entry of the U.S. into World War II; the harbor remains a major naval base, hosting the U.S. Pacific Fleet, the world's largest naval command.[12]

As Hawaii is the only state with no incorporated places below the county level,[13] the U.S. Census Bureau recognizes the approximate area commonly referred to as the "City of Honolulu"—not to be confused with the "City and County"—as a census county division (CCD).[14] As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the population of Honolulu was 350,964,[15] while that of the urban Honolulu census-designated place (CDP) was 802,459. The Urban Honolulu Metropolitan Statistical Area had 1,016,508 residents in 2020.[5] With over 300,000 residents, Honolulu is the most populous Oceanian city outside Australasia.[16][17]

Honolulu's favorable tropical climate, rich natural scenery, and extensive beaches make it a popular global destination for tourists. As of May 2021, the city receives the bulk of visitors to Hawaii, between 7,000 and 11,000 daily. This is below the 2019 passenger arrivals of 10,000 to 15,000 per day.[18]

History

Evidence of the first settlement of Honolulu by the original Polynesian migrants to the archipelago comes from oral histories and artifacts. These indicate that there was a settlement where Honolulu now stands in the 11th century.[19] After Kamehameha I conquered Oʻahu in the Battle of Nuʻuanu at Nuʻuanu Pali, he moved his royal court from the Island of Hawaiʻi to Waikīkī in 1804. His court relocated in 1809 to what is now downtown Honolulu. The capital was moved back to Kailua-Kona in 1812.

In November 1794, Captain William Brown of Great Britain was the first foreigner to sail into what is now Honolulu Harbor.[20] More foreign ships followed, making the port of Honolulu a focal point for merchant ships traveling between North America and Asia. The settlement grew from a handful of homes to a city in the early 19th century after it was selected by Kamehameha I as a replacement for his residence at Waikiki in 1810.[21]

In 1850, Kamehameha III moved the permanent capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom from Lahaina on Maui to Honolulu.[21] He and the kings that followed him transformed Honolulu into a modern capital, erecting buildings such as St. Andrew's Cathedral, ʻIolani Palace, and Aliʻiōlani Hale. At the same time, Honolulu became the center of commerce in the islands, with descendants of American missionaries establishing major businesses in downtown Honolulu.[22]

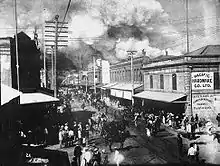

Despite the turbulent history of the late 19th century and early 20th century—such as the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, Hawaiʻi's subsequent annexation by the United States in 1898, followed by a large fire in 1900, and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941—Honolulu remained the capital, largest city, and main airport and seaport of the Hawaiian Islands.[23]

An economic and tourism boom following statehood brought rapid economic growth to Honolulu and Hawaiʻi. Modern air travel brings, as of 2007, 7.6 million visitors annually to the islands, with 62.3% entering at Honolulu International Airport.[24] Today, Honolulu is a modern city with numerous high-rise buildings, and Waikīkī is the center of the tourism industry in Hawaiʻi, with thousands of hotel rooms.

Geography

.jpg.webp)

According to the United States Census Bureau, the Urban Honolulu CDP has a total area of 68.4 square miles (177.2 km2), of which 7.9 square miles (20.5 km2), or 11.56%, is water.[25]

Honolulu is the most remote major city in the U.S. and one of the most remote in the world.[26] The closest location in mainland U.S. is the Point Arena Lighthouse in northern California, at 2,045 nautical miles (3,787 km).[27] (Nautical vessels require some additional distance to circumnavigate Makapuʻu Point.) The closest major city is San Francisco, California, at 2,300 miles (3,701 km).[26] However, islands off the Mexican coast and part of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska are slightly closer to Honolulu than the mainland.

The volcanic field of the Honolulu Volcanics is partially located inside the city.[28]

Neighborhoods, boroughs, and districts

- Downtown Honolulu is the financial, commercial, and governmental center of Hawaii. On the waterfront is Aloha Tower, which for many years was the tallest building in Hawaiʻi. Currently the tallest building is the 438-foot (134 m) tall First Hawaiian Center, located on King and Bishop Streets. The downtown campus of Hawaiʻi Pacific University is also located there.

- The Arts District Honolulu, located in both in downtown and Chinatown, is on the eastern edge of Chinatown. It is a 12-block area bounded by Bethel & Smith Streets and Nimitz Highway and Beretania Street – home to numerous arts and cultural institutions. It is located within the Chinatown Historic District, which includes the former Hotel Street Vice District.[29]

- The Capitol District is the eastern part of Downtown Honolulu. It is the current and historic center of Hawaiʻi's state government, incorporating the Hawaiʻi State Capitol, ʻIolani Palace, Honolulu Hale (City Hall), State Library, and the statue of King Kamehameha I, along with numerous government buildings.

- Kakaʻako is a light-industrial district between Downtown and Waikīkī that has seen a large-scale redevelopment effort in the past decade. It is home to two major shopping areas, Ward Warehouse and Ward Center. The Howard Hughes Corporation plans to transform Ward Centers into Ward Village over the next decade. The John A. Burns School of Medicine, part of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, is also located there. A Memorial to the Ehime Maru Incident victims is built at the Kakaʻako Waterfront Park.

- Ala Moana is a district between Kakaʻako and Waikīkī and the home of Ala Moana Center, the "World's largest open-air shopping center" and the largest shopping mall in Hawaiʻi.[30] Ala Moana Center boasts over 300 tenants and is a very popular location among tourists. Also in Ala Moana is the Honolulu Design Center and Ala Moana Beach Park, the second largest park in Honolulu.

- Waikīkī is the tourist district of Honolulu, located between the Ala Wai Canal and the Pacific Ocean next to Diamond Head. Numerous hotels, shops, and nightlife opportunities are located along Kalākaua and Kūhiō Avenues. It is a popular location for visitors and locals alike and attracts millions of visitors every year. A majority of the hotel rooms on Oʻahu are located in Waikīkī.

- Mānoa and Makiki are residential neighborhoods located in adjacent valleys just inland of downtown and Waikīkī. Mānoa Valley is home to the main campus of the University of Hawaii.

- Nuʻuanu and Pauoa are upper-middle-class residential districts located inland of downtown Honolulu. The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific is located in Punchbowl Crater fronting Pauoa Valley.

- Pālolo and Kaimukī are neighborhoods east of Mānoa and Makiki, inland from Diamond Head. Pālolo Valley parallels Mānoa and is a residential neighborhood. Kaimukī is primarily a residential neighborhood with a commercial strip centered on Waiʻalae Avenue running behind Diamond Head. Chaminade University is located in Kaimukī.

- Waiʻalae and Kāhala are upper-class districts of Honolulu located directly east of Diamond Head, where there are many high-priced homes. Also found in these neighborhoods are the Waialae Country Club and the five-star Kahala Hotel & Resort.

- East Honolulu includes the residential communities of ʻĀina Haina, Niu Valley, and Hawaiʻi Kai. These are considered upper-middle-class neighborhoods. The upscale gated communities of Waiʻalae ʻIki and Hawaiʻi Loa Ridge are also located here.

- Kalihi and Pālama are working-class neighborhoods with a number of government housing developments. Lower Kalihi, toward the ocean, is a light-industrial district.

- Salt Lake and Āliamanu are (mostly) residential areas built in extinct tuff cones along the western end of the Honolulu District, not far from Honolulu International Airport.

- Moanalua is two neighborhoods and a valley at the western end of Honolulu, and home to Tripler Army Medical Center.

- Kamehameha Heights is a northern suburb.[31]

Climate

Honolulu experiences a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen classification BSh), with a mostly dry summer season, due to a rain shadow effect.[32] Contrary to popular belief, despite temperatures that meet the tropical threshold of all months having a mean temperature of 64.4 °F (18.0 °C) or higher, it receives too little precipitation to be classified as such. Temperatures vary little throughout the months, with average high temperatures of 80–90 °F (27–32 °C) and average lows of 65–75 °F (18–24 °C) throughout the year. Temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on an average 32 days annually,[33][lower-alpha 2] with lows in the upper 50s °F (14–15 °C) occurring once or twice a year. The highest recorded temperature was 95 °F (35 °C) on September 19, 1994, and August 31, 2019.[33] The lowest recorded temperature was 52 °F (11 °C) on February 16, 1902, and January 20, 1969.[33]

The annual average rainfall is 16.41 inches (417 millimeters),[33] which mainly occurs during the winter months of October through early April, with very little rainfall during the summer. However, both seasons experience a similar number of rainy days. Light showers occur in summer, while heavier rain falls during winter. Honolulu has an average of 278 sunny days and 89.2 rainy days per year.

Although the city is situated in the tropics, hurricanes are quite rare. The last recorded hurricane that hit near Honolulu was Category 4 Hurricane Iniki in 1992. Tornadoes are also uncommon and usually strike once every 15 years. Waterspouts off the coast are also uncommon, hitting about once every five years.[34]

Honolulu falls under the USDA 12b Plant Hardiness zone.[35]

The average temperature of the sea ranges from 75.7 °F (24.3 °C) in March to 80.4 °F (26.9 °C) in September.[36]

| Climate data for Honolulu International Airport (1991−2020 normals,[lower-alpha 3] extremes 1877−present[lower-alpha 4]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

88 (31) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

93 (34) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 84.0 (28.9) |

84.6 (29.2) |

85.0 (29.4) |

86.4 (30.2) |

88.5 (31.4) |

89.1 (31.7) |

90.4 (32.4) |

91.1 (32.8) |

91.2 (32.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

87.3 (30.7) |

85.1 (29.5) |

91.7 (33.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 80.5 (26.9) |

80.5 (26.9) |

81.2 (27.3) |

83.1 (28.4) |

84.8 (29.3) |

86.9 (30.5) |

88.1 (31.2) |

88.8 (31.6) |

88.4 (31.3) |

86.9 (30.5) |

84.1 (28.9) |

81.8 (27.7) |

84.6 (29.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 73.6 (23.1) |

73.8 (23.2) |

74.7 (23.7) |

76.6 (24.8) |

78.2 (25.7) |

80.3 (26.8) |

81.6 (27.6) |

82.2 (27.9) |

81.6 (27.6) |

80.4 (26.9) |

78.0 (25.6) |

75.5 (24.2) |

78.0 (25.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 66.8 (19.3) |

67.1 (19.5) |

68.1 (20.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

71.5 (21.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

75.6 (24.2) |

74.8 (23.8) |

73.9 (23.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.5 (21.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 60.0 (15.6) |

60.2 (15.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

64.6 (18.1) |

66.3 (19.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

71.6 (22.0) |

71.8 (22.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

69.0 (20.6) |

66.1 (18.9) |

63.1 (17.3) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 52 (11) |

52 (11) |

53 (12) |

56 (13) |

60 (16) |

63 (17) |

63 (17) |

63 (17) |

64 (18) |

61 (16) |

57 (14) |

54 (12) |

52 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.84 (47) |

1.94 (49) |

2.36 (60) |

0.77 (20) |

0.82 (21) |

0.50 (13) |

0.52 (13) |

0.84 (21) |

0.88 (22) |

1.51 (38) |

2.25 (57) |

2.18 (55) |

16.41 (417) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.7 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 89.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.3 | 70.8 | 68.8 | 67.3 | 66.1 | 64.4 | 64.6 | 64.1 | 65.5 | 67.5 | 70.4 | 72.4 | 67.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 213.5 | 212.7 | 259.2 | 251.8 | 280.6 | 286.1 | 306.2 | 303.1 | 278.8 | 244.0 | 200.4 | 199.5 | 3,035.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 63 | 66 | 69 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 74 | 76 | 76 | 68 | 60 | 59 | 68 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[33][37][38] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Honolulu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 76.5 (24.7) |

75.9 (24.4) |

75.7 (24.3) |

76.9 (25.0) |

77.9 (25.5) |

78.7 (25.9) |

78.9 (26.0) |

79.5 (26.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

79.8 (26.5) |

78.5 (25.9) |

77.0 (25.0) |

78.0 (25.5) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 11.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 7 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 11 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 9.6 |

| Source #1: seatemperature.org[39] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weather Atlas[40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 22,907 | — | |

| 1900 | 39,306 | 71.6% | |

| 1910 | 52,183 | 32.8% | |

| 1920 | 83,327 | 59.7% | |

| 1930 | 137,582 | 65.1% | |

| 1940 | 179,326 | 30.3% | |

| 1950 | 248,034 | 38.3% | |

| 1960 | 294,194 | 18.6% | |

| 1970 | 324,871 | 10.4% | |

| 1980 | 365,048 | 12.4% | |

| 1990 | 365,272 | 0.1% | |

| 2000 | 371,657 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 337,256 | −9.3% | |

| 2020 | 350,964 | 4.1% | |

| Population 1890–2010.[15][41] | |||

.png.webp)

The population of Honolulu is 350,964 as of the 2020 U.S. Census, making it the 55th largest city in the U.S. The city's population was 337,256 at the 2010 U.S. Census.[15]

The residential neighborhood of East Honolulu is considered a separate census-designated place by the Census Bureau but is generally considered a part of the Honolulu urban core. The population of East Honolulu 50,922 as of 2020, increasing Honolulu's core population to over 400,000.[42]

In terms of race and ethnicity, 54.8% were Asian, 17.9% were White, 1.5% were Black or African American, 0.2% were Native American or Alaska Native, 8.4% were Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 0.8% were from "some other race", and 16.3% were from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 5.4% of the population.[15] In 1970, the Census Bureau reported Honolulu's population as 33.9% white and 53.7% Asian and Pacific Islander.[43]

Asian Americans represent the majority of Honolulu's population. The Asian ethnic groups are Japanese (19.9%), Filipinos (13.2%), Chinese (10.4%), Koreans (4.3%), Vietnamese (2.0%), Indians (0.3%), Laotians (0.3%), Thais (0.2%), Cambodians (0.1%), and Indonesians (0.1%). People solely of Native Hawaiian ancestry made up 3.2% of the population. Samoan Americans made up 1.5% of the population, Marshallese people make up 0.5% of the city's population, and Tongan people comprise 0.3% of its population. People of Guamanian or Chamorro descent made up 0.2% of the population and numbered 841 residents.[15]

Metropolitan Honolulu, which encompasses all of Oahu island, had a population of 953,207 as of the 2010 U.S. Census and 1,016,508 in the 2020 U.S. Census making it the 54th largest metropolitan area in the United States.[44][45]

Economy

The largest city and airport in the Hawaiian Islands, Honolulu acts as a natural gateway to the islands' large tourism industry, which brings millions of visitors and contributes $10 billion annually to the local economy. Honolulu's location in the Pacific also makes it a large business and trading hub, particularly between the East and the West. Other important aspects of the city's economy include military defense, research and development, and manufacturing.[46]

Among the companies based in Honolulu are:

- Alexander & Baldwin

- Bank of Hawaii

- Central Pacific Bank

- First Hawaiian Bank

- Hawaii Medical Service Association

- Hawaii Pacific Health

- Hawaiian Electric Industries

- Matson Navigation Company

- The Queen's Health Systems

Hawaiian Airlines,[47] Island Air,[48] and Aloha Air Cargo are headquartered in the city.[49][50] Prior to its dissolution, Aloha Airlines was headquartered in the city.[51] At one time Mid-Pacific Airlines had its headquarters on the property of Honolulu International Airport.[52]

In 2009, Honolulu had a 4.5% increase in the average price of rent, maintaining it in the second most expensive rental market ranking among 210 U.S. metropolitan areas.[53] Similarly, the general cost of living, including gasoline, electricity, and most foodstuffs, is much higher than the U.S. mainland, due to city and state having to import most goods.[26] One 2014 report found that cost of living expenses were 69% higher than the U.S. average.[54]

Since the only national banks in Hawaiʻi are all local, many visitors and new residents must get accustomed to different banks. First Hawaiian Bank is the largest and oldest bank in Hawaii[55] and their headquarters are at the First Hawaiian Center, the tallest office building in the State of Hawaii.[56]

Cultural institutions

Natural museums

The Bishop Museum is the largest of Honolulu's museums. It is endowed with the state's largest collection of natural history specimens and the world's largest collection of Hawaiiana and Pacific culture artifacts.[57] The Honolulu Zoo is the main zoological institution in Hawaii while the Waikīkī Aquarium is a working marine biology laboratory. The Waikīkī Aquarium is partnered with the University of Hawaii and other universities worldwide. Established for appreciation and botany, Honolulu is home to several gardens: Foster Botanical Garden, Liliʻuokalani Botanical Garden, Walker Estate, among others.

Performing arts

Established in 1900, the Honolulu Symphony is the second oldest US symphony orchestra west of the Rocky Mountains. Other classical music ensembles include the Hawaii Opera Theatre. Honolulu is also a center for Hawaiian music. The main music venues include the Hawaii Theatre, the Neal Blaisdell Center Concert Hall and Arena, and the Waikīkī Shell.

Honolulu also includes several venues for live theater, including the Diamond Head Theatre and Kumu Kahua Theatre.

Visual arts

Various institutions for the visual arts are located in Honolulu.

The Honolulu Museum of Art is endowed with the largest collection of Asian and Western art in Hawaiʻi. It also has the largest collection of Islamic art, housed at the Shangri La estate. Since the merger of the Honolulu Academy of Arts and The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu (now called the Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House) in 2011, the museum is also the only contemporary art museum in the state. The contemporary collections are housed at main campus (Spalding House) in Makiki and a multi-level gallery in downtown Honolulu at the First Hawaiian Center. The museum hosts a film and video program dedicated to arthouse and world cinema in the museum's Doris Duke Theatre, named for the museum's historic patroness Doris Duke.[58]

The Hawaii State Art Museum (also downtown) boasts pieces by local artists as well as traditional Hawaiian art. The museum is administered by the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts.

Honolulu also annually holds the Hawaii International Film Festival (HIFF). It showcases some of the best films from producers all across the Pacific Rim and is the largest "East meets West" style film festival of its sort in the United States.

Tourist attractions

- Ala Moana Center

- Aloha Tower

- Bishop Museum

- Diamond Head

- Hanauma Bay

- Honolulu Museum of Art

- Honolulu Zoo

- ʻIolani Palace

- Lyon Arboretum

- National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

- USS Arizona Memorial

- Waikīkī Aquarium

- Waikiki Beach

- Waikiki Trolley

- International Market Place

- Kapi'olani Park

Sports

Honolulu's tropical climate lends itself to year-round activities. In 2004, Men's Fitness magazine named Honolulu the fittest city in the United States.[59] Honolulu has three large road races:

- The Great Aloha Run is held annually on Presidents' Day.

- The Honolulu Marathon, held annually on the second Sunday in December, draws more than 20,000 participants each year, about half to two thirds of them from Japan.

- The Honolulu Triathlon is an Olympic distance triathlon event governed by USA Triathlon and partly by the Japanese. Held annually in May since 2004, there is an absence of a sprint course.

Ironman Hawaii was first held in Honolulu. It was the first ever Ironman triathlon event and is also the world championship.

The Waikiki Roughwater Swim race is held annually off the beach of Waikiki. Founded by Jim Cotton in 1970, the course is 2.384 miles (3.837 km) and spans from the New Otani Hotel to the Hilton Rainbow Tower.[60]

Fans of spectator sports in Honolulu generally support the football, volleyball, basketball, rugby union, rugby league, and baseball programs of the University of Hawaii at Manoa.[61] High school sporting events, especially football, are especially popular.

Honolulu has no professional sports teams, with any prospective teams being forced to conduct extremely long travels for away games in the continental states. It was the home of the Hawaii Islanders (Pacific Coast League, 1961–87), The Hawaiians (World Football League, 1974–75), Team Hawaii (North American Soccer League, 1977), and the Hawaiian Islanders (af2, 2002–04).

The NCAA football Hawaii Bowl is played in Honolulu. Honolulu has also hosted the NFL's annual Pro Bowl each February from 1980 to 2009. After the 2010 and 2015 games were played in Miami Gardens and Glendale, respectively, the Pro Bowl was once again in Honolulu from 2011 to 2014 with 2016 the most recent.[62][63] From 1993 to 2008, Honolulu hosted Hawaii Winter Baseball, featuring minor league players from Major League Baseball, Nippon Professional Baseball, Korea Baseball Organization, and independent leagues.

In 2018, the Honolulu Little League team qualified for that year's Little League World Series tournament. The team went undefeated en route to the United States championship game, where it bested Georgia's Peachtree City American Little League team 3–0. In the world championship game, the team faced off against South Korea's South Seoul Little League team. Hawaii pitcher Ka'olu Holt threw a complete game shutout while striking out 8, and Honolulu Little League – again by a score of 3–0 – secured the victory, capturing the 2018 Little League World Series championship as well as Hawaii's third overall title at the Little League World Series.[64]

Venues

Venues for spectator sports in Honolulu include:

- Les Murakami Stadium at UH-Mānoa (baseball)

- Neal S. Blaisdell Center Arena (basketball)

- Stan Sheriff Center at UH-Mānoa (basketball and volleyball)

Aloha Stadium, a venue for American football and soccer, is located in Halawa near Pearl Harbor, just outside Honolulu.[65]

Government

Rick Blangiardi was elected mayor of Honolulu County on August 8, 2020, and began serving as the county's 15th mayor on January 2, 2021. The municipal offices of the City and County of Honolulu, including Honolulu Hale, the seat of the city and county, are located in the Capitol District, as are the Hawaii state government buildings.[66]

The Capitol District is within the Honolulu census county division (CCD), the urban area commonly regarded as the "City" of Honolulu. The Honolulu CCD is located on the southeast coast of Oʻahu between Makapuu and Halawa. The division boundary follows the Koʻolau crestline, so Makapuʻu Beach is in the Ko'olaupoko District. On the west, the division boundary follows Halawa Stream, then crosses Red Hill and runs just west of Aliamanu Crater, so that Aloha Stadium, Pearl Harbor (with the USS Arizona Memorial), and Hickam Air Force Base are actually all located in the island's Ewa CCD.[67]

The Hawaii Department of Public Safety operates the Oʻahu Community Correctional Center, the jail for the island of Oʻahu, in Honolulu CCD.[68]

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Honolulu. The main Honolulu Post Office is located by the international airport at 3600 Aolele Street.[69] Federal Detention Center, Honolulu, operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, is in the CDP.[70]

Education and research

Colleges and universities

Colleges and universities in Honolulu include Honolulu Community College, Kapiolani Community College, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Chaminade University, and Hawaii Pacific University.[50] UH Mānoa houses the main offices of the University of Hawaii System.[78]

Research institutions

.jpg.webp)

Honolulu is home to three renowned international affairs research institutions. The Pacific Forum, one of the world's leading Asia-Pacific policy research institutes and one of the first organizations in the United States to focus exclusively on Asia, has its main office on Bishop Street in downtown Honolulu. The East–West Center (EWC), an education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and understanding among the peoples and nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States, is headquartered in Mānoa, Honolulu. The Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS), a U.S. Department of Defense institute is based in Waikīkī, Honolulu. APCSS addresses regional and global security issues and supports the U.S. Pacific Command by developing and sustaining relationships among security practitioners and national security establishments throughout the region.

Public primary and secondary schools

Hawaii Department of Education operates public schools in Honolulu.[79] Public high schools within the CDP area include Wallace Rider Farrington, Kaiser, Kaimuki, Kalani, Moanalua, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt.[50] It also includes the Hawaii School for the Deaf and the Blind, the statewide school for blind and deaf children. There is a charter school, University Laboratory School.

Private primary and secondary schools

As of 2014 almost 38% of K-12 students in the Honolulu area attend private schools.[80]

Private schools include Academy of the Pacific, Damien Memorial School, Hawaii Baptist Academy, ʻIolani School, Lutheran High School of Hawaii, Kamehameha Schools, Maryknoll School, Mid-Pacific Institute, La Pietra, Punahou School, Sacred Hearts Academy, St. Andrew's Priory School, Saint Francis School, Saint Louis School, the Education Laboratory School, Saint Patrick School, Trinity Christian School, and Varsity International School. Hawaii has one of the nation's highest rate of private school attendance.[81]

Public libraries

Hawaii State Public Library System operates public libraries. The Hawaii State Library in the CDP serves as the main library of the system,[82] while the Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, also in the CDP area, serves handicapped and blind people.[83]

Branches in the CDP area include Aiea, Aina Haina, Ewa Beach, Hawaiʻi Kai, Kahuku, Kailua, Kaimuki, Kalihi-Palama, Kaneohe, Kapolei, Liliha, Mānoa, McCully-Moiliili, Mililani, Moanalua, Wahiawa, Waialua, Waianae, Waikīkī-Kapahulu, Waimanalo, and Waipahu.[84]

Weekend educational programs

The Hawaiʻi Japanese School – Rainbow Gakuen (ハワイレインボー学園 Hawai Reinbō Gakuen), a supplementary weekend Japanese school, holds its classes in Kaimuki Middle School in Honolulu and has its offices in another building in Honolulu.[85] The school serves overseas Japanese nationals.[86] In addition Honolulu has other weekend programs for the Japanese, Chinese, and Spanish languages.[87]

Media

Honolulu is served by one daily newspaper, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, along with a magazine, Honolulu Magazine, several radio stations and television stations, among other media. Local news agency and CNN-affiliate Hawaii News Now broadcasts and is headquartered out of Honolulu.

Honolulu and the island of Oʻahu has also been the location for many film and television projects, including Hawaii Five-O (1968 TV series), Magnum, P.I. and Lost.

Transportation

Air

Located at the western end of the CDP, Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL) is the principal aviation gateway to the state of Hawaii. Kalaeloa Airport is primarily a commuter facility used by unscheduled air taxis, general aviation and transient and locally based military aircraft.

Highways

Honolulu has been ranked as having the nation's worst traffic congestion, beating former record holder Los Angeles. Drivers waste on average over 58 hours per year on congested roadways.[88] The following freeways, part of the Interstate Highway System serve Honolulu:

Interstate H-1, western terminous is at Kapolei where you can connect to the Farrington Highway. The H-1 passes Hickam Air Force Base and Honolulu International Airport, runs through pearl city before heading downtown into Honolulu continues eastward through Makiki and Kaimuki, ending at Waialae/Kahala and start of the Kalanianole Highway.

Interstate H-1, western terminous is at Kapolei where you can connect to the Farrington Highway. The H-1 passes Hickam Air Force Base and Honolulu International Airport, runs through pearl city before heading downtown into Honolulu continues eastward through Makiki and Kaimuki, ending at Waialae/Kahala and start of the Kalanianole Highway. Interstate H-201—also known as the Moanalua Freeway and sometimes numbered as its former number, Hawaiʻi State Rte. 78—connects two points along H-1: at Aloha Stadium and Fort Shafter. Close to H-1 and Aloha Stadium, H-201 has an exchange with the western terminus of Interstate H-3 to the windward side of Oahu (Kaneohe). This complex of connecting ramps, some directly between H-1 and H-3, is in Halawa.

Interstate H-201—also known as the Moanalua Freeway and sometimes numbered as its former number, Hawaiʻi State Rte. 78—connects two points along H-1: at Aloha Stadium and Fort Shafter. Close to H-1 and Aloha Stadium, H-201 has an exchange with the western terminus of Interstate H-3 to the windward side of Oahu (Kaneohe). This complex of connecting ramps, some directly between H-1 and H-3, is in Halawa. Interstate H-2 Connects at a junction near Waipau and Pearl City with the H-1 freeway. The H-2 freeway will take you up to Schofield barracks before ending at Wahiawa where it connect to the north shore.

Interstate H-2 Connects at a junction near Waipau and Pearl City with the H-1 freeway. The H-2 freeway will take you up to Schofield barracks before ending at Wahiawa where it connect to the north shore. Interstate H-3 Connects at a junction near Halawa Heights. This interstate highway will take you from Halawa heights through the Ko'olau Range to Kaneohe. Its final termination is at Marine Corps Base Hawaii. Exit 15 is the last exit before entering Marine Corps Base Hawaii.

Interstate H-3 Connects at a junction near Halawa Heights. This interstate highway will take you from Halawa heights through the Ko'olau Range to Kaneohe. Its final termination is at Marine Corps Base Hawaii. Exit 15 is the last exit before entering Marine Corps Base Hawaii.

Other major highways that link Honolulu CCD with other parts of the Island of Oahu are:

Pali Highway, State Rte. 61, crosses north over the Koolau range via the Pali Tunnels to connect to Kailua and Kaneohe on the windward side of the Island.

Pali Highway, State Rte. 61, crosses north over the Koolau range via the Pali Tunnels to connect to Kailua and Kaneohe on the windward side of the Island. Likelike Highway, State Rte. 63, also crosses the Koolau to Kaneohe via the Wilson Tunnels.

Likelike Highway, State Rte. 63, also crosses the Koolau to Kaneohe via the Wilson Tunnels. Kalanianaole Highway, State Rte. 72, runs eastward from Waialae/Kahala to Hawaiʻi Kai and around the east end of the island to Waimanalo Beach.

Kalanianaole Highway, State Rte. 72, runs eastward from Waialae/Kahala to Hawaiʻi Kai and around the east end of the island to Waimanalo Beach.- Kamehameha Highway, State Rte. 80, 83, 99 and 830, runs westward from near Hickam Air Force Base to Aiea and beyond, eventually running through the center of the island and ending in Kaneohe.

- Farrington Highway, State Rte 93 runs western leeward Oahu from Kaena Point through Waianae and Makaha before the start of the H-1. State Rte 930 starts east to west in the north shore connecting you from Wailua to Kaena Point

Like most major American cities, the Honolulu metropolitan area experiences heavy traffic congestion during rush hours, especially to and from the western suburbs of Kapolei, ʻEwa Beach, Aiea, Pearl City, Waipahu, and Mililani.

There is a Hawaiʻi Electric Vehicle Demonstration Project (HEVDP).[89]

Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation

In November 2010, voters approved a charter amendment to create a public transit authority to oversee the planning, construction, operation and future extensions to Honolulu's future rail system. The Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) currently includes a 10-member board of directors; three members appointed by the mayor, three members selected by the Honolulu City Council, and the city and state transportation directors.[90] The opening of the first phase of the Honolulu Rail Transit is delayed until approximately March 2021, as HART canceled the initial bids for the first nine stations and intends to rebid the work as three packages of three stations each, and allow more time for construction in the hope that increased competition on smaller contracts will drive down costs;[91] initial bids ranged from $294.5 million to $320.8 million, far surpassing HART's budget of $184 million.[92]

Bus

Established by former Mayor Frank F. Fasi as the replacement for the Honolulu Rapid Transit Company (HRT), Honolulu's TheBus system was honored in 1994–1995 and 2000–2001 by the American Public Transportation Association as "America's Best Transit System". TheBus operates 107 routes serving Honolulu and most major cities and towns on Oʻahu. TheBus comprises a fleet of 531 buses, and is run by the non-profit corporation Oʻahu Transit Services in conjunction with the city Department of Transportation Services. As of 2006, Honolulu was ranked fourth for highest per-capita use of mass transit in the United States.[93]

Para-transit Options

The island also features TheHandi-Van.[94] available for riders who require para-transit operations. To be eligible for these parantransit service, individuals must meet the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). TheHandi-Van has a fare of $2.00, available Mondays – Sundays from 4:00 am – 1:00 am. There is a 24 hours per day service but only within 3/4 of a mile of TheBus route 2[95] and route 40.[96] TheHandi-Van comprises a fleet of 160 buses. Additionally the parantransit branch also run's Human Services Transportation Coordination (HSTCP), which mainly provides transportation for people with disabilities, older adults, and people with limited incomes, assisted by the Committee for Accessible Transportation (CAT). Both organizations work together to provide transportation for elderly and persons with disabilities.

Rail

Currently, there is no urban rail transit system in Honolulu, although electric street railways were operated in Honolulu by the now-defunct Honolulu Rapid Transit Company prior to World War II. Predecessors to the Honolulu Rapid Transit Company were the Honolulu Rapid Transit and Land Company (began 1903) and Hawaiian Tramways (began 1888).[97]

The City and County of Honolulu is currently constructing the 20-mile (32 km) rail transit line that will connect Honolulu with cities and suburban areas near Pearl Harbor and in the Leeward and West Oahu regions. The Honolulu High-Capacity Transit Corridor Project is aimed at alleviating traffic congestion for West Oʻahu commuters while being integral in the westward expansion of the metropolitan area. The project, however, has been criticized by opponents of rail for its cost, delays, and potential environmental impacts, but the line is expected to have large ridership.

Bicycle sharing

Since June 28, 2017, Bikeshare Hawaii administers the bicycle sharing program in O'ahu while Secure Bike Share operates the Biki system. Most Biki stations are located between Chinatown/Downtown and Diamond Head, however an expansion in late 2018 added more stations towards the University of Hawaii Manoa Campus, Kapi'olani Community College, Makiki, and Kalihi area.[98][99][100][101] The GoBiki.org website has a Biki stations map.

Modal characteristics

According to the 2016 American Community Survey (five-year average), 56 percent of Urban Honolulu residents commuted to work by driving alone, 13.8 percent carpooled, 11.7 used public transportation, and 8.7 percent walked. About 5.7 commuted by bike, taxi, motorcycle or other forms of transportation, while 4.1 percent worked at home.[102]

The city of Honolulu has a high percentage of households without a motor vehicle. In 2015, 16.6 percent of Honolulu households lacked a car, which increased slightly to 17.2 percent in 2016 – in comparison, the United States national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Honolulu averaged 1.4 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[103]

Public safety

The Honolulu Police Department is the primary law enforcement agency for the city and county of Honolulu and serves the entire Oahu Island. Honolulu Police Department has a mixed fleet of marked patrol cars and unmarked along with a subsidized vehicle program in place. Marked vehicles are white with blue stripes and white lettering HONOLULU POLICE. The Honolulu Police Departments offers officers of a certain rank to purchase a private vehicle for police use. Subsidized vehicles are unmarked but will have a small blue roof light on top of the vehicle.[104] Subsidized vehicles can be any make, model and color but does require to follow department rules and guidelines. Honolulu Police and Hawaii County Police on the big island are the only departments in the state of Hawaii and the US to have subsidized vehicles in place. Honolulu Police along with other city, county law enforcement in Hawaii uses blue lights for their vehicles. They also keep their cruise blue lights on while on patrol.[105]

The Honolulu Fire Department provides fire fighting services and emergency medical services on the island of Oahu. Fire trucks are painted yellow.[106]

Sister cities

Honolulu's sister cities are:[107]

Baguio, Philippines, 1991

Baguio, Philippines, 1991 Baku, Azerbaijan, 1998

Baku, Azerbaijan, 1998 Bruyères, France, 1960

Bruyères, France, 1960 Cali, Colombia, 2012

Cali, Colombia, 2012 Candon, Philippines, 2015

Candon, Philippines, 2015 Caracas, Venezuela, 1990

Caracas, Venezuela, 1990 Cebu City, Philippines, 1990

Cebu City, Philippines, 1990 Chengdu, China, 2011

Chengdu, China, 2011 Chigasaki, Japan, 2014

Chigasaki, Japan, 2014 Fengxian (Shanghai), China, 2012

Fengxian (Shanghai), China, 2012 Funchal, Portugal, 1979

Funchal, Portugal, 1979 Fuzhou, China, 2021[108]

Fuzhou, China, 2021[108] Haikou, China, 1985

Haikou, China, 1985 Noreña, Spain, 1960

Noreña, Spain, 1960 Hiroshima, Japan, 1959

Hiroshima, Japan, 1959 Huế, Vietnam, 1995

Huế, Vietnam, 1995 Incheon, South Korea, 2003

Incheon, South Korea, 2003 Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 1962

Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 1962 Kyzyl, Russia, 2004

Kyzyl, Russia, 2004 Laoag, Philippines, 1969

Laoag, Philippines, 1969 Majuro, Marshall Islands, 2001

Majuro, Marshall Islands, 2001 Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2005

Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2005 Manila, Philippines, 1980

Manila, Philippines, 1980 Mombasa, Kenya, 2000

Mombasa, Kenya, 2000 Mumbai, India, 1970

Mumbai, India, 1970 Nagaoka, Japan, 2012

Nagaoka, Japan, 2012 Naha, Japan, 1960

Naha, Japan, 1960 Qinhuangdao, China, 2010

Qinhuangdao, China, 2010 Rabat, Morocco, 2007

Rabat, Morocco, 2007 San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1985

San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1985 Seoul, South Korea, 1973

Seoul, South Korea, 1973 Sintra, Portugal, 1998

Sintra, Portugal, 1998 Uwajima, Japan, 2004

Uwajima, Japan, 2004 Vigan, Philippines, 2003

Vigan, Philippines, 2003 Zhangzhou, China, 2012

Zhangzhou, China, 2012 Zhongshan, China, 1997

Zhongshan, China, 1997

See also

- List of tallest buildings in Honolulu

Notes

- For statistical purposes, the US Census Bureau considers Honolulu to be a Census-designated place (CDP), rather than a city.[8]

- There have been as many as 116 days (in 1995) that reached 90 °F (32 °C), and as recently as, 2012, no days.[33] The average is comparable to Philadelphia despite being slightly warmer during the summer.

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- Official records for Honolulu have been kept at downtown from February 1877 to September 1949, and at Honolulu Int'l since October 1949. For more information, see ThreadEx

References

- Honolulu And Kapolei Share City Lights 2005, Honolulu, HI, USA: Honolulu County, Hawaii, November 29, 2005, archived from the original on November 5, 2013, retrieved June 30, 2012

- "About the City, Official Website of the City and County of Honolulu". City and County of Honolulu. City and County of Honolulu. April 24, 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2004. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- "Geographic Ientifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Urban Honolulu CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "U.S. Census website". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- "Honolulu". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Dictionary Reference

- US Census Bureau – Population Division. "Places Cartographic Boundary Files Descriptions and Metadata". Washington, D.C., USA: U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

Hawaii is the only state that has no incorporated places recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau. All places shown in the data products for Hawaii are CDPs. By agreement with the state of Hawaii, the U.S. Census Bureau does not show data separately for the city of Honolulu, which is coextensive with Honolulu County.

- "About the City". Honolulu.gov. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "etymonline.com entry for Honolulu". Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- "This Is Your City and County of Honolulu Government". honolulu.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet". www.cpf.navy.mil. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing, 2000 [United States]: Summary File 2, Hawaii". ICPSR Data Holdings. March 19, 2002. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "2010 Census – Honolulu CCD Population". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Urban Honolulu CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Ash, Russell (1998). The top 10 of everything. p. 100.

- Long-Range Futures Research: An Application of Complexity Science, Robert Samet, 2009, 272

- "Daily Passenger Counts". dbedt.hawaii.gov. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Honolulu History –". Hellohonolulu.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Kuykendall, Ralph S. (June 1923). "A Northwest Trader at the Hawaiian Islands". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. Oregon Historical Society. 24 (2): 121. JSTOR 20610240.

- Daws, Gavan (1967). "Honolulu in the 19th Century: Notes on the Emergence of Urban Society in Hawaii". The Journal of Pacific History. Taylor & Francis. 2: 77–78, 83. doi:10.1080/00223346708572103. JSTOR 25167896.

- "About the City, Official Web Site for The City and County of Honolulu". .honolulu.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Honolulu History". Honolulu-city.com. December 7, 1941. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "2007 Annual Visitor Research Report" (PDF). Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism, State of Hawaii. July 1, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Urban Honolulu CDP, Hawaii". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Gill, Nicholas (August 19, 2015). "Where is the world's most remote city?". The Guardian. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- Microsoft Streets and Trips 2007 Software, Copyright 2006 by Microsoft Corp. et al.

- Stearns, Harold T.; Vaksvik, Knute N. (1935). "Geology and ground-water resources of the island of Oahu, Hawaii". Maui Publishing Company, Limited. p. 536.

- "Artsdistricthonolulu.com". Artsdistricthonolulu.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Hawaii's Premier Shopping, Entertainment, and Dining Destination". Ala Moana Center. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Hawaii Life: Kamehameha Heights, Honolulu Oahu Real Estate for Sale – Just Listed Kamehameha Heights Homes, Kamehameha Heights Condos, Kamehameha Heights Land". Hawaii Life: Kamehameha Heights, Honolulu Oahu Real Estate for Sale – Just Listed Kamehameha Heights Homes, Kamehameha Heights Condos, Kamehameha Heights Land. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "Monthly weather forecast and climate Honolulu, HI". Weather Atlas. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- USDA.govAgricultural Research Center, PRISM Climate Group Oregon State University. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". USDA. USDA. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- Ltd, Copyright Global Sea Temperatures – A-Connect. "Honolulu Sea Temperature October Average, United States – Sea Temperatures". World Sea Temperatures.

- "Station: Honolulu INTL AP, HI". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- "WMO Climate Normals for HONOLULU, OAHU, HI 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- "Honolulu Sea Temperature January Average, United States Water Temperatures". Copyright Global Sea Temperatures – A-Connect Ltd. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- "Honolulu, Hawaii, USA – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- "Census Of Population And Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: East Honolulu CDP, Hawaii". www.census.gov. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- "Hawaii – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Honolulu County, Hawaii". www.census.gov. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- "Metropolitan Growth: 2020 Census | Newgeography.com". www.newgeography.com. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- "Honolulu Economy". City-Data.com. Advameg Inc. 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- "Corporate Headquarters". Hawaiinair.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- "General Contact Information". Honolulu, HI, USA: Island Air. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- "Locations Archived May 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Aloha Air Cargo. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- "Honolulu CDP, HI Archived February 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- "Aloha Airlines, Inc." BusinessWeek. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- "World Airline Directory." Flight International. May 16, 1981. 1452. "Head Office: Honolulu International Airport, Hawaii, USA."

- Gomes, Andrew (March 24, 2010). "Honolulu rents still 2nd priciest in U.S." the.honoluluadvertiser.com. Honolulu, HI, USA: Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- "The 20 Most Expensive Cities in the U.S." Kiplinger. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- Hill, Tiffany (October 8, 2008). "The Centenarians". Honolulu Magazine. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Honolulu | Statistics | EMPORIS". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Welcome to the Bishop Museum". Bishopmuseum.org. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Honolulu Museum of Art – Doris Duke Theatre". Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "Honolulu ranked No. 1 fittest city for second year". Pacific Business News. Pacific.bizjournals.com. January 5, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "WAIKIKI ROUGHWATER SWIM". www.waikikiroughwaterswim.com. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "University of Hawaii at Manoa". Uhm.hawaii.edu. May 2, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Arnett, Paul; Reardon, Dave (December 30, 2008). "Miami tackles Pro Bowl". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- "Pro Bowl shifting to Super Bowl site for 2015". The Chicago Tribune. Reuters. April 9, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- "Little League World Series 2018: Live updates for Hawaii-South Korea championship game". Sporting News. August 26, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- "Halawa CDP, Hawaii Archived December 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- City and County of Honolulu (January 18, 2012), "Historic Honolulu (The Capitol District)", Official Web Site for The City and County of Honolulu, Honolulu, HI, USA: City and County of Honolulu, archived from the original on November 19, 2004, retrieved July 14, 2012

- United States Census Bureau (February 2, 2002), CENSUS 2000 BLOCK MAP: HONOLULU CCD 5702.01 (PDF), Washington, D.C., USA: U.S. Census Bureau, retrieved July 14, 2012

- "Oahu Community Correctional Center". Hawaii Department of Public Safety. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- "Post Office Location – Honolulu." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- "FDC Honolulu Contact Information." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on December 30, 2009.

- "Visa & Travel Archived November 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Consulate-General of Japan in Honolulu. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- "Location Archived December 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Consulate-General of South Korea in Honolulu. Retrieved on January 10, 2009.

- "Other Philippine Missions in the U.S.." Consulate-General of the Philippines in Chicago. Retrieved on January 10, 2009.

- "Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Honolulu".

- "Department of Foreign Affairs, Overseas Embassies, Consulates, and Missions." Department of Foreign Affairs (Federated States of Micronesia). Retrieved on January 10, 2009.

- "Australian Consulate-General in Honolulu, United States of America." Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved on January 10, 2009.

- "Foreign Mission Archived June 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Republic of the Marshall Islands. Retrieved on January 28, 2009.

- Magin, Janis L. (July 1, 2007). "Land deals could breathe new life into Moili'ili". American City Business Journals.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Honolulu County, HI" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 22, 2022. - Text list

- Wong, Alia (March 17, 2014). "Living Hawaii: Many Families Sacrifice to Put Kids in Private Schools". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "Despite tuition increases, private school enrollment remains steady". Hawaii Nes Now.

- "Hawaii State Library". Hawaii State Public Library System. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- "Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped". Hawaii State Public Library System. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- "Library Branches". Honolulu, HI, USA: Hawaii State Public Library System. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- "Home page." Hawaii Japanese School – Rainbow Gakuen. Retrieved on April 16, 2015. "事務所住所: 2454 South Beretania St., #202 Honolulu, HI 96826" and "授業実施校: Kaimuki Middle School"

- "Government of Japan to honor 3 from Hawaii today" (Archive). Honolulu Advertiser. November 3, 2007. Retrieved on April 16, 2015.

- Randolph, April. "Tot talk goes global" (Archive). Honolulu Advertiser. March 19, 2008. Retrieved on April 16, 2015.

- "The Worst Traffic in America? It's not Los Angeles". Yahoo! Autos. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- "Hawaii Center for Advanced Transportation Technologies". High Technology Development Corporation. Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation. "HART – Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation". Honolulu: Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation. Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- "HART cancels bids for first 9 rail stations". KITV. September 10, 2014. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- honolulutransit.org Honolulu Transit E-Blast (PDF) Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine August 18, 2014.

- "Top Transit Cities 2006". National Transit Database. February 11, 2008. Archived from the original on July 20, 2010.

- "Public Transit". www.honolulu.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Route 2" (PDF).

- "Route 40" (PDF).

- "Hawaii's History in 1888 – Hawaii History – 1888". Hawaiihistory.org. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Bikeshare Hawaii". Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "10 new Biki stops to be installed from Downtown to Waikiki". KITV. August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- Zielke, Aydee (April 2, 2014). "Honolulu's bike share program ready to roll in summer 2015!". HHF Planners. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Bikeshare Hawaii selects PBSC Urban Solutions as partner to supply bikes for Honolulu". American City Business Journals. Honolulu. December 8, 2015.

- "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. December 9, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "HPD officers say enforcing 30-year old policy endangers their lives". www.hawaiinewsnow.com. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- "New directive requires Kauai police to keep blue lights on at all times during patrols". KHON2. December 18, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- "The Hawaiian Fire Departments". Fire Services Information. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- "International Relations and Sister-City Program" (official website). City and County of Honolulu. 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "Fuzhou, Honolulu forge sister-city ties". news.cn. Xinhua. October 22, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

.jpg.webp)

_(slight_cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)