Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples[lower-alpha 1] are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original peoples.[4] The term Indigenous was first, in its modern context, used by Europeans, who used it to differentiate the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from the European settlers of the Americas and from the Africans who were brought to the Americas as enslaved people. The term may have first been used in this context by Sir Thomas Browne in 1646, who stated "and although in many parts thereof there be at present swarms of Negroes serving under the Spaniard, yet were they all transported from Africa, since the discovery of Columbus; and are not indigenous or proper natives of America."[5][6]

Peoples are usually described as "Indigenous" when they maintain traditions or other aspects of an early culture that is associated with the first inhabitants of a given region.[7] Not all indigenous peoples share this characteristic, as many have adopted substantial elements of a colonizing culture, such as dress, religion or language. Indigenous peoples may be settled in a given region (sedentary), exhibit a nomadic lifestyle across a large territory, or be resettled, but they are generally historically associated with a specific territory on which they depend. Indigenous societies are found in every inhabited climate zone and continent of the world except Antarctica.[8] There are approximately five thousand Indigenous nations throughout the world.[9]

Indigenous peoples' homelands have historically been colonized by larger ethnic groups, who justified colonization with beliefs of racial and religious superiority, land use or economic opportunity.[10] Thousands of Indigenous nations throughout the world are currently living in countries where they are not a majority ethnic group.[11] Indigenous peoples continue to face threats to their sovereignty, economic well-being, languages, ways of knowing, and access to the resources on which their cultures depend. Indigenous rights have been set forth in international law by the United Nations, the International Labour Organization, and the World Bank.[12] In 2007, the UN issued a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) to guide member-state national policies to the collective rights of Indigenous peoples, including their rights to protect their cultures, identities, languages, ceremonies, and access to employment, health, education and natural resources.[13]

Estimates of the total global population of Indigenous peoples usually range from 250 million to 600 million.[14] Official designations and terminology of who is considered Indigenous vary between countries. In settler states colonized by Europeans, such as in the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania, Indigenous status is generally unproblematically applied to groups directly descended from the peoples who have lived there prior to European settlement. In Asia and Africa, where the majority of Indigenous peoples live, Indigenous population figures are less clear and may fluctuate dramatically as states tend to underreport the population of Indigenous peoples, or define them by different terminology.[15]

Etymology

Indigenous is derived from the Latin word indigena, meaning "sprung from the land, native".[16] The Latin indigena is based on the Old Latin indu "in, within" + gignere "to beget, produce". Indu is an extended form of the Proto-Indo-European en or "in".[17] The origins of the term indigenous are not related in any way to the origins of the term Indian, which, until recently, was commonly applied to indigenous peoples of the Americas.[18]

Autochthonous originates from the Greek αὐτός autós meaning self/own, and χθών chthon meaning Earth. The term is based in the Indo-European root dhghem- (earth). The earliest documented use of this term was in 1804.[19]

Definitions

As a reference to a group of people, the term indigenous first came into use by Europeans who used it to differentiate the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from enslaved Africans. It may have first been used in this context by Sir Thomas Browne. In Chapter 10 of Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646) entitled "Of the Blackness of Negroes", Browne wrote "and although in many parts thereof there be at present swarms of Negroes serving under the Spaniard, yet were they all transported from Africa, since the discovery of Columbus; and are not indigenous or proper natives of America."[5][6]

In the 1970s, the term was used as a way of linking the experiences, issues, and struggles of groups of colonized people across international borders. At this time 'indigenous people(s)' also began to be used to describe a legal category in Indigenous law created in international and national legislation. The use of the 's' in 'peoples' recognizes that there are real differences between different Indigenous peoples.[20][21] James Anaya, former Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, defined Indigenous peoples as "living descendants of pre-invasion inhabitants of lands now dominated by others. They are culturally distinct groups that find themselves engulfed by other settler societies born of forces of empire and conquest".[22][23]

National definitions

Throughout history, different states designate the groups within their boundaries that are recognized as indigenous peoples according to international or national legislation by different terms. Indigenous people also include people indigenous based on their descent from populations that inhabited the country when non-Indigenous religions and cultures arrived—or at the establishment of present state boundaries—who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions, but who may have been displaced from their traditional domains or who may have resettled outside their ancestral domains.[24]

The status of the Indigenous groups in the subjugated relationship can be characterized in most instances as an effectively marginalized or isolated in comparison to majority groups or the nation-state as a whole.[25] Their ability to influence and participate in the external policies that may exercise jurisdiction over their traditional lands and practices is very frequently limited. This situation can persist even in the case where the Indigenous population outnumbers that of the other inhabitants of the region or state; the defining notion here is one of separation from decision and regulatory processes that have some, at least titular, influence over aspects of their community and land rights.[26]

The presence of external laws, claims and cultural mores either potentially or actually act to variously constrain the practices and observances of an Indigenous society. These constraints can be observed even when the Indigenous society is regulated largely by its own tradition and custom. They may be purposefully imposed, or arise as unintended consequence of trans-cultural interaction. They may have a measurable effect, even where countered by other external influences and actions deemed beneficial or that promote Indigenous rights and interests.[24]

United Nations

The first meeting of the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP) was on 9 August 1982 and this date is now celebrated as the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples.[27] In 1982 the group accepted a preliminary definition by José R. Martínez-Cobo, Special Rapporteur on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations:[28]

Indigenous communities, peoples, and nations are those that, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.[29]

The primary impetus in considering indigenous identity comes from considering the historical impacts of European colonialism. A 2009 United Nations report published by the Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues stated:[30]

For centuries, since the time of their colonization, conquest or occupation, indigenous peoples have documented histories of resistance, interface or cooperation with states, thus demonstrating their conviction and determination to survive with their distinct sovereign identities. Indeed, Indigenous peoples were often recognized as sovereign peoples by states, as witnessed by the hundreds of treaties concluded between Indigenous peoples and the governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and others. And yet as Indigenous populations dwindled, and the settler populations grew ever more dominant, states became less and less inclined to recognize the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples themselves, at the same time, continued to adapt to changing circumstances while maintaining their distinct identity as sovereign peoples.[31]

The World Health Organization defines Indigenous populations as follows: "communities that live within, or are attached to, geographically distinct traditional habitats or ancestral territories, and who identify themselves as being part of a distinct cultural group, descended from groups present in the area before modern states were created and current borders defined. They generally maintain cultural and social identities, and social, economic, cultural and political institutions, separate from the mainstream or dominant society or culture."[32]

'Blue-water' hypothesis

The largely Eurocentric so-called "blue-water" hypothesis suggests that only trans-oceanic (European) colonizers can become the "other" to peoples defined - by contrast - as "indigenous".[33] Bruce Robbins writes: [34]

Those who would like to define indigenous peoples as exclusively victims of European colonialism have put forward the so-called 'blue-water' hypothesis, according to which colonialism is only colonialism if it involved the crossing of water in a ship, not if it was the result of conquest by land. [...] this hypothesis has been strongly urged by China, which posits that it contains no indigenous peoples. But other Asian nations, like the Philippines, Japan, and Indonesia, have rejected this idea, and even China has muted its references. [...] the effort to save the unique guilt of Europe would plunge us into complete absurdity, absolving European Russia while it also sacrifices the indigenous status of the peoples of the Caucasus and Siberia along with the indigeneity of all other Asians.

History

Classical antiquity

Greek sources of the Classical period acknowledge indigenous people whom they referred to as "Pelasgians". Ancient writers saw these people either as the ancestors of the Greeks,[35] or as an earlier group of people who inhabited Greece before the Greeks.[36] The disposition and precise identity of this former group is elusive, and sources such as Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus give varying, partially mythological accounts. Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his book, Roman Antiquities, gives a synoptic interpretation of the Pelasgians based on the sources available to him then, concluding that Pelasgians were Greek.[37] Greco-Roman society flourished between 330 BCE and 640 CE and undertook successive campaigns of conquest that subsumed more than half of the known world of the time. But because already existent populations within other parts of Europe at the time of classical antiquity had more in common - culturally speaking - with the Greco-Roman world, the intricacies involved in expansion across the European frontier were not so contentious relative to indigenous issues.[38]

Catholic Church and doctrine of discovery

The doctrine of discovery is a legal and religious concept, tied to the Roman Catholic Church, which rationalized and "legalized" colonization and the conquering of indigenous peoples in the eyes of Christianized Europeans. The roots of the doctrine go back as far as the fifth-century popes and leaders in the church who had ambitions of forming a global Christian commonwealth. The Crusades (1096-1271) built on this ambition of a holy war against those whom the church saw as infidels. Pope Innocent IV's writings from 1240 were particularly influential. He argued that Christians were justified in invading and acquiring infidels' lands because it was the church's duty to control the spiritual health of all humans on Earth.[10]

The doctrine developed further in the 15th century after the conflict between the Teutonic Knights and Poland over control of "pagan" Lithuania. At the Council of Constance (1414) the Knights argued that their claims were "authorized by papal proclamations dating from the time of the Crusades [which] allowed the outright confiscation of the property and sovereign rights of heathens". The Council disagreed, stating that non-Christians had claims to rights of sovereignty and property under European natural law. However, the Council upheld that conquests could "legally" occur if non-Christians refused to comply with Christianization and European natural law. This effectively meant that peoples who were not considered "civilized" by European standards or otherwise refused to assimilate under Christian authority were subject to war and forced assimilation: "Christians simply refused to recognize the right of non-Christians to remain free of Christian dominion."[10] Christian Europeans had already begun invading and colonizing lands outside of Europe before the Council of Constance, demonstrating how the doctrine was applied to non-Christian indigenous peoples outside Europe. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the indigenous peoples of the Canary Islands, known as Guanches, became the subject of some colonizers' attention. The Guanches had remained undisturbed and relatively "forgotten" by Europeans until Portugal began surveying the island for potential settlement in 1341. In 1344 the Papacy issued a bull which assigned the islands to Castile, a kingdom in Spain. In 1402, the Spanish began efforts to invade and colonize the islands.[39] In 1436 Pope Eugenius IV issued a new papal edict, Romanus Pontifex, which authorized Portugal to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity and to control the Canary Islands on behalf of the pope.[10] The Guanches resisted European invasion until the surrender of the Guanche kings of Tenerife to Spain in 1496. The invaders brought destruction and diseases to the Guanche people, whose identity and culture disappeared as a result.[39][40][41]

As Portugal expanded southward into North Africa in the 15th century, subsequent popes added new edicts which extended Portuguese authority over indigenous peoples. In 1455, Pope Nicholas V re-issued the Romanus Pontifex with more direct language, authorizing Portugal "to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans" as well as allowing non-Christians to be placed in slavery and have their property stolen. As stated by Robert J. Miller, Jacinta Ruru, Larissa Behrendt, and Tracey Lindberg, the doctrine developed over time "to justify the domination of non-Christian, non-European peoples and the confiscations of their lands and rights". Because Portugal was granted "permissions" by the papacy to expand in Africa, Spain was moved to expand westward across the Atlantic Ocean, searching to convert and conquer indigenous peoples in what became known as the "New World". The papal-endorsed division of the world between Spain and Portugal was formalized in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494.[10]

Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella hired Christopher Columbus and dispatched him in 1492 to colonize and bring new lands under the Spanish crown. Columbus "discovered" a few islands in the Caribbean as early as 1493, and Ferdinand and Isabella immediately asked the pope to "ratify" the discovery. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued the Inter caetera divinai, which affirmed that since the islands had been "undiscovered by others" that they were now under Spanish authority. Alexander granted Spain any lands that it discovered as long as they had not been "previously possessed by any Christian owner". The beginnings of European colonialism in the "New World" effectively formalized the Doctrine of Discovery into international law, which at that time meant law that was agreed upon by Spain, Portugal, and the Catholic Church. Indigenous peoples were not consulted or included in these arrangements.[10]

European colonialism in the New World

Spain issued the Spanish Requirement of 1513 (Requerimiento), a document intended to inform indigenous peoples that "they must accept Spanish missionaries and sovereignty or they would be annihilated". The document was supposed to be read to indigenous peoples so that they theoretically could accept or reject the proposal before any war against them could be waged: "the Requerimiento informed the Natives of their natural law obligations to hear the gospel and that their lands had been donated to Spain". Refusal by Indigenous peoples meant that, in the Spaniards' eyes, war could "justifiably" be waged against them. Many conquistadors apparently feared that, if given the option, indigenous peoples would actually accept Christianity, which would legally not permit invasion of their lands and the theft of their belongings. Legal scholars Robert J. Miller, Jacinta Rura, Larissa Behrendt, and Tracey Lindberg record that this commonly resulted in Spanish invaders reading the document aloud "in the night to the trees" or reading it "to the land from their ships". The scholars remark: "so much for legal formalism and the free will and natural law rights of New World Indigenous peoples."[42]

England and France, both still Catholic countries in 1493, worked to "re-interpret" the Doctrine of Discovery to serve their own colonial interests. In the 16th century, England established a new interpretation of the Doctrine: "the new theory, primarily developed by English legal scholars, argued that the Catholic King Henry VII of England would not violate the 1493 papal bulls, which divided the world for the Spanish and Portuguese". This interpretation was also supported by Elizabeth I's legal advisors in the 1580s and effectively set a precedent among European colonial nations that the first Christian nation to occupy land was the "legal" owner and that this had to be respected in international law. This rationale was used in the colonization of what became Britain's Thirteen Colonies in mainland east-coast North America. King James I stated in the First Virginia Charter (1606) and in the Charter to the Council of New England (1620) that colonists could be given property rights because the lands were "not now actually possessed by any Christian Prince or People". English monarchs decreed that colonists should spread Christianity "to those [who] as yet live in Darkness and miserable Ignorance of the true Knowledge and Worship of God, [and] to bring the Infidels and Savages, living in those parts, to human civility, and to a settled and quiet Government".[42]

This approach to colonization of newly "discovered" lands resulted in an acceleration of exploration and land-claiming, particularly by France, England, and Holland. Land claims were made through symbolic "rituals of discovery" that were performed to illustrate the colonizing state's legal claim to the land. Markers of possession such as crosses, flags, and plates claiming possession and other symbols became important in this contest to claim indigenous lands. In 1642, Dutch explorers were ordered to set up posts and a plate that asserted their intention to establish a colony on the land. In the 1740s, French explorers buried lead plates at various locations to reestablish their 17th-century land claims to Ohio country. The French plates were later discovered by indigenous peoples of the Ohio River. Upon contact with English explorers, the English noted that the lead plates were monuments "of the renewal of [French] possession" of the land. In 1774, Captain James Cook attempted to invalidate Spain's land-claims to Tahiti by removing Spanish marks of possession and then proceeding to set up English marks of possession. When the Spanish learned of this action, they quickly sent an explorer to reestablish their claim to the land.[42]

European colonialists developed the legal concept of terra nullius (literally: nobody's land) or vacuum domicilium (empty or vacant house) to validate their lands claims over indigenous peoples' homelands. This concept formalized the idea that lands which were not being used in a manner that European legal systems approved of were open for European colonization. Historian Henry Reynolds captured this perspective in his statement that "Europeans regarded North America as a vacant land that could be claimed by right of discovery." These new legal concepts developed in order to diminish reliance on papal authority to authorize or justify colonization claims.[42]

As the "rules" of colonization became established in legal doctrines agreed upon by between European colonial powers, methods of laying claims to indigenous lands continued to expand rapidly. As encounters between European colonizers and indigenous populations in the rest of the world accelerated, so did the introduction of infectious diseases, which sometimes caused local epidemics of extraordinary virulence. For example, smallpox, measles, malaria, yellow fever, and other diseases were unknown in pre-Columbian Americas and Oceania.

Settler independence and continuing colonialism

Although the establishment of colonies throughout the world by various European powers aimed to expand those powers' wealth and influence, settler populations in some localities became anxious to assert their own autonomy. For example, settler independence movements in thirteen of the British American colonies were successful by 1783, following the American Revolutionary War. This resulted in the establishment of the United States of America as an entity separate from the British Empire. The United States continued and expanded European colonial doctrine through adopting the Doctrine of Discovery as the law of the American federal government in 1823 with the US Supreme Court case Johnson v. M'Intosh. Statements at the Johnson court case illuminated the United States' support for the principles of the discovery doctrine:[43]

The United States ... [and] its civilized inhabitants now hold this country. They hold, and assert in themselves, the title by which it was acquired. They maintain, as all others have maintained, that discovery gave an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or by conquest; and gave also a right to such a degree of sovereignty, as the circumstances of the people would allow them to exercise. ... [This loss of native property and sovereignty rights was justified, the Court said, by] the character and religion of its inhabitants ... the superior genius of Europe ... [and] ample compensation to the [Indians] by bestowing on them civilization and Christianity, in exchange for unlimited independence.

Population and distribution

Indigenous societies range from those who have been significantly exposed to the colonizing or expansionary activities of other societies (such as the Maya peoples of Mexico and Central America) through to those who as yet remain in comparative isolation from any external influence (such as the Sentinelese and Jarawa of the Andaman Islands).

Precise estimates for the total population of the world's Indigenous peoples are very difficult to compile, given the difficulties in identification and the variances and inadequacies of available census data. The United Nations estimates that there are over 370 million Indigenous people living in over 70 countries worldwide.[44] This would equate to just fewer than 6% of the total world population. This includes at least 5,000 distinct peoples[45] in over 72 countries.

Contemporary distinct Indigenous groups survive in populations ranging from only a few dozen to hundreds of thousands and more. Many Indigenous populations have undergone a dramatic decline and even extinction, and remain threatened in many parts of the world. Some have also been assimilated by other populations or have undergone many other changes. In other cases, Indigenous populations are undergoing a recovery or expansion in numbers.

Certain Indigenous societies survive even though they may no longer inhabit their "traditional" lands, owing to migration, relocation, forced resettlement or having been supplanted by other cultural groups. In many other respects, the transformation of culture of Indigenous groups is ongoing, and includes permanent loss of language, loss of lands, encroachment on traditional territories, and disruption in traditional ways of life due to contamination and pollution of waters and lands.

Environmental and economic benefits of Indigenous stewardship of land

A WRI report mentions that "tenure-secure" Indigenous lands generates billions and sometimes trillions of dollars' worth of benefits in the form of carbon sequestration, reduced pollution, clean water and more. It says that tenure-secure Indigenous lands have low deforestation rates,[46][47] they help to reduce GHG emissions, control erosion and flooding by anchoring soil, and provide a suite of other local, regional and global ecosystem services. However, many of these communities find themselves on the front lines of the deforestation crisis, and their lives and livelihoods threatened.[48][49][50]

Indigenous people and environment

Misconceptions about complexity of the relationship between indigenous population and their natural habitat has informed Westerners view of California's "wild Eden" which may have led to misguided ideas on policy designs to preserve this "wilderness". Assuming that the natural habitat automatically provided food and nourishment for indigenous population placed practices toward the exploitative end of the spectrum of human interactions with nature as only "hunter-gatherers". There is evidence that tells another story and describes this relationship as a "calculated tempered use of nature as active agents of environmental change and stewardship". This distorted view of "wilderness" as uninhabited nature has resulted in removal of indigenous inhabitants to preserve "the wild". In reality, depriving the land from indigenous people management such as controlled burning, harvesting, and seed scattering has yielded dense understory shrubbery or tickets of young trees which are inhospitable to life. Current assessments indicate that indigenous peoples used land sustainably, without causing substantial losses of biodiversity, for thousands of years.[51]

A goal is to ascertain an unbiased view of indigenous population resource management practices instead of literature that often assumes their impact to be entirely negative or of little to no effect. Although, there is evidence of negative impacts, particularly, on large animals by over-exploitation,[52][53][54][55] there is a plethora of evidence from historical literature, archaeological findings, ecological field studies, and native people's culture that paints another picture in which indigenous land management practices were largely successful in promoting habitat heterogeneity, increasing biodiversity, and maintaining certain vegetation types. These findings show that indigenous practices sustain lives while conserving natural resources and may be prove essential in improving our own relationship with natural resources. Setting aside "wilderness" is still imperative given our continued population growth, however, that growth itself requires another way of thinking in "re-creating specific human-ecosystem associations". Human-ecological history of land should inform resource management policies today. This history cannot be simplified into dichotomies of "hunter-gatherers" vs. "agriculturalists" and should entail more complex models. Indigenous practices are at the roots of this history, present a prime example of this complex relationship, and show how weaving their way of life into our culture allows us to meet our needs without destroying natural resources. It is really important that studying ethnoscience is not guarantee that every local societies and indigenous people must have special science to consider important.[56]

Contradictory findings

Recently, it has come to light that the deforestation rate of Indonesian rainforests has been far greater than estimated. Such a rate could not have been the product of globalization as understood before; rather, it seemed that ordinary local people dependent on these forests for their livelihoods are in fact "joining distant corporations in creating uninhabitable landscapes." Popular theories of globalization cannot accommodate such phenomena. These conventions "package all cultural development into a single program" and assert that powerless minorities and communities have adjusted themselves according to global forces. However, in the case of Indonesian deforestation, global forces alone could not explain the rate of destruction. Therefore, a new approach is in which global forces are themselves "congeries of local/global interaction" with unexpected encounters across different populations and cultures. Then, destruction of forests in excess of market needs could be seen as an unexpected result of the encounter between global forces that feed the market needs and local livelihoods that depend on the same forests. Trying to capture these unexpected encounters under the idea of "friction" where culture is "continually co-produced in interactions" that are made up of "creative qualities of interconnection across difference" might seem awkward, unequal, or unstable. These "messy and surprising" features of such interactions across difference are exactly what should inform our models of cultural production. In this framework, friction makes global connection powerful and effective but at the same time, it has the capacity to disrupt and even cause cataclysms in its smooth operation as a well-oiled machine. A well-documented example of such process is the industrialization of rubber, which was made possible by European savage conquests, competitive passions of colonial botany, resistance strategies of peasants, wars, advancement of technology and science, and the struggle over industrial goals and hierarchies. Attention to friction provides a unique opportunity to create a theoretical framework under which developing an "ethnographic" account of globalization becomes a possibility. Within such an ethnographic account, Indonesian encounters can "shape the shared space in which Indonesian and non-Indonesian jointly experience fears, tensions, and uncertainties."[57]

Studying indigenous knowledge and their relationship with nature does not make it obligatory for indigenous people to have local knowledge to consider their rights. Criticizing environmentalist accounts of indigenous populations that are typically motivated by trying to protect their landscape and surroundings from globalization forces might be a good idea. To do so requires a two-fold strategy where description of an indigenous society and their habitat must make a "narratable" story, and be of some "value" to westerners so that it can generate international support for preserving their culture and environment. Using Eastern Penan populations to demonstrate how environmentalists transform Penan's indigenous "knowledge" of their forest by pulling from ethnographies of other forest population, e.g., in Amazon forests. In doing so, they corrupt the cultural diversity of indigenous by framing them into a single narrative in the name of preserving the biodiversity of their habitat. In case of Easter Penan, three categories of misrepresentation is noticeable:The Molong concept is purely a stewardship notion of resource management. communities or individuals take ownership of specific trees and harvest them in such a way that allows them to exploit long-term. This notion has gained an etherealism in environmentalist writings according to western romantic notions of indigenous to tell a more connecting story. Landscape features and particularly their names in local languages provided geographical and historical information for Penan people; whereas in environmentalist accounts, it has turned into a spiritual practice where trees and rivers represent forest spirits that are sacred to the Penan people. A typical stereotype of some environmentalists' approach to ecological ethnography is to present indigenous "knowledge" of nature as "valuable" to the outside world because of its hidden medicinal benefits. In reality, eastern Penan populations do not identify a medicinal stream of "knowledge". These misrepresentations in the "narrative" of indigeneity and "value" of indigenous knowledge might have been helpful for Penan's people in their struggle to protect their environment, but it might also have disastrous consequences. What happens if another case did not fit in this romantic narrative, or another indigenous knowledge did not seem beneficial to the outside world. These people were being uprooted in the first place because their communities did not fit well with the state's system of values.[58]

Indigenous peoples by region

Indigenous populations are distributed in regions throughout the globe. The numbers, condition and experience of Indigenous groups may vary widely within a given region. A comprehensive survey is further complicated by sometimes contentious membership and identification.

Africa

.jpg.webp)

In the post-colonial period, the concept of specific Indigenous peoples within the African continent has gained wider acceptance, although not without controversy. The highly diverse and numerous ethnic groups that comprise most modern, independent African states contain within them various peoples whose situation, cultures and pastoralist or hunter-gatherer lifestyles are generally marginalized and set apart from the dominant political and economic structures of the nation. Since the late 20th century these peoples have increasingly sought recognition of their rights as distinct Indigenous peoples, in both national and international contexts.

Though the vast majority of African peoples are indigenous in the sense that they originate from that continent, in practice, identity as an Indigenous people per the modern definition is more restrictive, and certainly not every African ethnic group claims identification under these terms. Groups and communities who do claim this recognition are those who, by a variety of historical and environmental circumstances, have been placed outside of the dominant state systems, and whose traditional practices and land claims often come into conflict with the objectives and policies implemented by governments, companies and surrounding dominant societies.

Americas

Indigenous peoples of the Americas are broadly recognized as being those groups and their descendants who inhabited the region before the arrival of European colonizers and settlers (i.e., Pre-Columbian). Indigenous peoples who maintain, or seek to maintain, traditional ways of life are found from the high Arctic north to the southern extremities of Tierra del Fuego.

The impacts of historical and ongoing European colonization of the Americas on Indigenous communities have been in general quite severe, with many authorities estimating ranges of significant population decline primarily due to disease, land theft and violence. Several peoples have become extinct, or very nearly so. But there are and have been many thriving and resilient Indigenous nations and communities.

North America

North America is sometimes referred to by Indigenous peoples as Abya Yala or Turtle Island.

In Mexico, about 25 million people self-reported as Indigenous in 2015. Some estimates put the Indigenous population of Mexico as high as 40-65 million people, making it the country with the highest Indigenous population in North America.[59][60] In the southern states of Oaxaca (65.73%) and Yucatán (65.40%), the majority of the population is Indigenous, as reported in 2015. Other states with high populations of Indigenous peoples include Campeche (44.54%), Quintana Roo, (44.44%), Hidalgo, (36.21%), Chiapas (36.15%), Puebla (35.28%), and Guerrero (33.92%).[61][62]

Indigenous peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations,[63] Inuit[64] and Métis.[65] The descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" have fallen into disuse in Canada.[66][67] More currently, the term "Aboriginal" is being replaced with "Indigenous". Several national organizations in Canada changed their names from "Aboriginal" to "Indigenous". Most notable was the change of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) in 2015, which then split into Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Development Canada in 2017.[68] According to the 2016 Census, there are around 1,670,000 Indigenous peoples in Canada.[69] There are currently over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, such as the Cree, Mohawk, Mikmaq, Blackfoot, Coast Salish, Innu, Dene and more, with distinctive Indigenous cultures, languages, art, and music.[70][71] First Nations peoples signed 11 numbered treaties across much of what is now known as Canada between 1871 and 1921, except in parts of British Columbia.

The Inuit have achieved a degree of administrative autonomy with the creation in 1999 of the territories of Nunavik (in Northern Quebec), Nunatsiavut (in Northern Labrador) and Nunavut, which was until 1999 a part of the Northwest Territories. The autonomous territory of Greenland within the Kingdom of Denmark is also home to a recognised Indigenous and majority population of Inuit (about 85%) who settled the area in the 13th century, displacing the Indigenous European Greenlandic Norse.[72][73][74][75]

In the United States, the combined populations of Native Americans, Inuit and other Indigenous designations totaled 2,786,652 (constituting about 1.5% of 2003 U.S. census figures). Some 563 scheduled tribes are recognized at the federal level, and a number of others recognized at the state level.

Central and South America

In some countries (particularly in Latin America), Indigenous peoples form a sizable component of the overall national population — in Bolivia, they account for an estimated 56–70% of the total nation, and at least half of the population in Guatemala and the Andean and Amazonian nations of Peru. In English, Indigenous peoples are collectively referred to by different names that vary by region, age and ethnicity of speakers, with no one term being universally accepted. While still in use in-group, and in many names of organizations, "Indian" is less popular among younger people, who tend to prefer "Indigenous" or simply "Native, with most preferring to use the specific name of their tribe or Nation instead of generalities. In Spanish or Portuguese speaking countries, one finds the use of terms such as índios, pueblos indígenas, amerindios, povos nativos, povos indígenas, and, in Peru, Comunidades Nativas (Native Communities), particularly among Amazonian societies like the Urarina[76] and Matsés. In Chile, there the most populous indigenous peoples are the Mapuches in the Center-South and the Aymaras in the North.[77] Rapa Nui of Easter Island, who are a Polynesian people, are the only non-Amerindian indigenous people in Chile.

Indigenous peoples make up 0.4% of all Brazilian population, or about 700,000 people.[78] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although the majority of them live in Indian reservations in the North and Center-Western part of the country. On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted peoples in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted peoples.[79]

Asia

The vast regions of Asia contain the majority of the world's present-day indigenous populations, about 70% according to IWGIA figures.

Western Asia

- Armenians: are the Indigenous people of the Armenian Highlands.[80][81][82][83] There are currently more Armenians living outside their ancestral homeland because of the Armenian genocide of 1915.

- Anatolian Greeks, including the Pontic Greeks and Cappadocian Greeks, are the Greek-speaking minorities that existed in Anatolia millennia before Turkic conquest. They are indigenous to Asiatic Turkey.[80][84][85] Most were either killed in the Greek genocide or displaced during the following population exchange; however, some remain in Turkey.[86][87] There has been a Greek presence in Anatolia since at least the 1000s BCE,[88][89] and Greek traders visited western Anatolia beginning in 1900 BCE.[90]

- Assyrians: are indigenous to Mesopotamia.[91][92][80][93] They claim descent from the ancient Neo-Assyrian Empire, and lived in what was Assyria, their original homeland, and still speak dialects of Aramaic, the official language of the Assyrian Empire.

- Georgians: are indigenous to Georgia.

- Kurds: are one of the Indigenous peoples of Mesopotamia.[94][95][96][97][98]

- Yazidis: are indigenous to Upper Mesopotamia.[99][80][100][101][102]

There are competing claims that Palestinian Arabs and Jews are indigenous to historic Palestine/the Land of Israel.[103][104][105] The argument entered the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in the 1990s, with Palestinians claiming Indigenous status as a pre-existing population displaced by Jewish settlement, and currently constituting a minority in the State of Israel.[106][107] Israeli Jews have also claimed indigeneity, citing religious and historical connections to the land as their ancient homeland; some have disputed the authenticity of Palestinian claims.[108][109][110] In 2007, the Negev Bedouin were officially recognised as Indigenous peoples of Israel by the United Nations.[111] This has been criticised both by scholars associated with the Israeli state, who dispute the Bedouin's claim to indigeneity,[112] and those who argue that recognising just one group of Palestinians as indigenous risks undermining others' claims and "fetishising" nomadic cultures.[113]

South Asia

India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean are also home to several Indigenous groups such as the Andamanese of Strait Island, the Jarawas of Middle Andaman and South Andaman Islands, the Onge of Little Anadaman Island and the uncontacted Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island. They are registered and protected by the Indian government.

In Sri Lanka, the Indigenous Vedda people constitute a small minority of the population today.

North Asia

The Russians invaded Siberia and conquered the indigenous people in the 17th–18th centuries.

Nivkh people are an ethnic group indigenous to Sakhalin, having a few speakers of the Nivkh language, but their fisher culture has been endangered due to the development of oil field of Sakhalin from 1990s.[114]

In Russia, definition of "indigenous peoples" is contested largely referring to a number of population (less than 50,000 people), and neglecting self-identification, origin from indigenous populations who inhabited the country or region upon invasion, colonization or establishment of state frontiers, distinctive social, economic and cultural institutions.[115][7] Thus, indigenous peoples of Russia such as Sakha, Komi, Karelian and others are not considered as such due to the size of the population (more than 50,000 people), and consequently they "are not the subjects of the specific legal protections."[116] The Russian government recognizes only 40 ethnic groups as indigenous peoples, even though there are other 30 groups to be counted as such. The reason of nonrecognition is the size of the population and relatively late advent to their current regions, thus indigenous peoples in Russia should be numbered less than 50,000 people.[117][118][119]

East Asia

Ainu people are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaidō, the Kuril Islands, and much of Sakhalin. As Japanese settlement expanded, the Ainu were pushed northward and fought against the Japanese in Shakushain's Revolt and Menashi-Kunashir Rebellion, until by the Meiji period they were confined by the government to a small area in Hokkaidō, in a manner similar to the placing of Native Americans on reservations.[120] In a ground-breaking 1997 decision involving the Ainu people of Japan, the Japanese courts recognized their claim in law, stating that "If one minority group lived in an area prior to being ruled over by a majority group and preserved its distinct ethnic culture even after being ruled over by the majority group, while another came to live in an area ruled over by a majority after consenting to the majority rule, it must be recognized that it is only natural that the distinct ethnic culture of the former group requires greater consideration."[121]

The Dzungar Oirats are indigenous to the Dzungaria in Northern Xinjiang.

The Sarikoli Pamiris are indigenous to Tashkurgan in Xinjiang.

The Tibetans are indigenous to Tibet.

The Ryukyuan people are indigenous to the Ryukyu Islands.

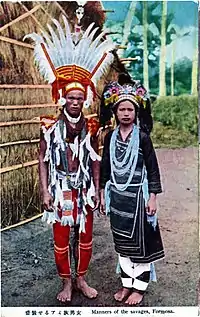

The languages of Taiwanese aborigines have significance in historical linguistics, since in all likelihood Taiwan was the place of origin of the entire Austronesian language family, which spread across Oceania.[122][123][124]

In Hong Kong, the indigenous inhabitants of the New Territories are defined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration as people descended through the male line from a person who was in 1898, before Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory.[125] There are several different groups that make up the indigenous inhabitants, the Punti, Hakka, Hoklo, and Tanka. All are nonetheless considered part of the Cantonese majority, although some like the Tanka have been shown to have genetic and anthropological roots in the Baiyue people, the pre-Han Chinese inhabitants of Southern China.

Southeast Asia

The Malay Singaporeans are the indigenous people of Singapore, inhabiting it since the Austronesian migration. They had established the Kingdom of Singapura back in the 13th century. The name Singapore itself comes from the Malay word Singapura (Singa=Lion, Pura=City) which means the Lion City.

Dayak People are one of the native groups of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located inBorneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory, and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable.

The Cham are the indigenous people of the former state of Champa which was conquered by Vietnam in the Cham–Vietnamese wars during Nam tiến. The Cham in Vietnam are only recognized as a minority, and not as an indigenous people by the Vietnamese government despite being indigenous to the region.

The Degar (Montagnards) are indigenous to Central Highlands (Vietnam) and were conquered by the Vietnamese in the Nam tiến.

The Khmer Krom are the indigenous people of the Mekong Delta and Saigon which were acquired by Vietnam from Cambodian King Chey Chettha II in exchange for a Vietnamese princess.

In Indonesia, there are 50 to 70 million people who classify as indigenous peoples.[126] However, the Indonesian government does not recognize the existence of indigenous peoples, classifying every Native Indonesian ethnic group as "indigenous" despite the clear cultural distinctions of certain groups.[127] This problem is shared by many other countries in the ASEAN region.

In the Philippines, there are 135 ethno-linguistic groups, majority of which are considered as indigenous peoples by mainstream indigenous ethnic groups in the country. The indigenous people of Cordillera Administrative Region and Cagayan Valley in the Philippines are the Igorot people. The indigenous peoples of Mindanao are the Lumad peoples and the Moro (Tausug, Maguindanao Maranao and others) who also live in the Sulu archipelago. There are also others sets of indigenous peoples in Palawan, Mindoro, Visayas, and the rest central and south Luzon. The country has one of the largest indigenous peoples population in the world.

In Myanmar, indigenous peoples include the Shan, the Karen, the Rakhine, the Karenni, the Chin, the Kachin and the Mon. However, there are more ethnic groups that are considered indigenous, for example, the Akha, the Lisu, the Lahu or the Mru, among others.[128]

Europe

Various ethnic groups have lived in Europe for millennia. However, the UN recognizes very few indigenous populations within Europe, which are confined to the far north and far east of the continent.

Notable indigenous minority populations in Europe that are recognized by the UN include the Sámi peoples of northern Norway, Sweden, and Finland and northwestern Russia (in an area also referred to as Sápmi); the Uralic Nenets, Samoyed, and Komi peoples of northern Russia;[129] the Circassians of southern Russia and the North Caucasus; the Crimean Tatars, Krymchaks, and Crimean Karaites of Crimea in Ukraine; the Basques of Basque Country, Spain and southern France; the Sorbs of Germany and Poland, the Irish Travellers of the island of Ireland,[130][131] and the Albanians of the Balkans.

The Gaels, a Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and Isle of Man associated with the Goidelic languages, haven't received official recognition of being an indigenous people as per the UN definition, or as the victims of colonization. However, this argument has been advanced by notable historians such as Michael Newton, Alastair MacIntosh and Iain Mackinnon.[132][133][134]

Oceania

In Australia, the indigenous populations are the Aboriginal Australian peoples (comprising many different nations and language groups) and the Torres Strait Islander peoples (also with sub-groups). These two groups are often referred to as Indigenous Australians,[135] although terms such as First Nations[136] and First Peoples are also used.[137]

Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian peoples originally populated many of the present-day Pacific Island countries in the Oceania region over the course of thousands of years. European, American, Chilean and Japanese colonial expansion in the Pacific brought many of these areas under non-indigenous administration, mainly during the 19th century. During the 20th century, several of these former colonies gained independence and nation-states formed under local control. However, various peoples have put forward claims for indigenous recognition where their islands are still under external administration; examples include the Chamorros of Guam and the Northern Marianas, and the Marshallese of the Marshall Islands. Some islands remain under administration from Paris, Washington, London or Wellington.

The remains of at least 25 miniature humans, who lived between 1,000 and 3,000 years ago, were recently found on the islands of Palau in Micronesia.[138]

In most parts of Oceania, indigenous peoples outnumber the descendants of colonists. Exceptions include Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii. In New Zealand the Māori population estimate at 30 June 2021 is 17% of the population.[139] Māori are indigenous to Polynesia and settled New Zealand after migrations probably in the 13th century.[140] A treaty with the British, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 by approximately 45 Māori leaders,[141] following in 1835 the signing of He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene: the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand as a statement of sovereignty by Māori to the wider world and an assertion of the Indigenous rights of Māori in New Zealand, this led to the Treaty of Waitangi.[142][143]

A majority of the Papua New Guinea population is indigenous, with more than 700 different nationalities recognized in a total population of 8 million.[144] The country's constitution and key statutes identify traditional or custom-based practices and land tenure, and explicitly set out to promote the viability of these traditional societies within the modern state. However, conflicts and disputes concerning land use and resource rights continue between indigenous groups, the government, and corporate entities.

Indigenous rights and other issues

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

|

| Governmental organizations |

|

| NGOs and political groups |

|

| Issues |

|

| Legal representation |

|

| Category |

Indigenous peoples confront a diverse range of concerns associated with their status and interaction with other cultural groups, as well as changes in their inhabited environment. Some challenges are specific to particular groups; however, other challenges are commonly experienced.[145] These issues include cultural and linguistic preservation, land rights, ownership and exploitation of natural resources, political determination and autonomy, environmental degradation and incursion, poverty, health, and discrimination.

The interactions between indigenous and non-indigenous societies throughout history and contemporarily have been complex, ranging from outright conflict and subjugation to some degree of mutual benefit and cultural transfer. A particular aspect of anthropological study involves investigation into the ramifications of what is termed first contact, the study of what occurs when two cultures first encounter one another. The situation can be further confused when there is a complicated or contested history of migration and population of a given region, which can give rise to disputes about primacy and ownership of the land and resources.

Wherever indigenous cultural identity is asserted, common societal issues and concerns arise from the indigenous status. These concerns are often not unique to indigenous groups. Despite the diversity of indigenous peoples, it may be noted that they share common problems and issues in dealing with the prevailing, or invading, society. They are generally concerned that the cultures and lands of indigenous peoples are being lost and that indigenous peoples suffer both discrimination and pressure to assimilate into their surrounding societies. This is borne out by the fact that the lands and cultures of nearly all of the peoples listed at the end of this article are under threat. Notable exceptions are the Sakha and Komi peoples (two northern indigenous peoples of Russia), who now control their own autonomous republics within the Russian state, and the Canadian Inuit, who form a majority of the territory of Nunavut (created in 1999). Despite the control of their territories, many Sakha people have lost their lands as a result of the Russian Homestead Act, which allows any Russian citizen to own any land in the Far Eastern region of Russia. In Australia, a landmark case, Mabo v Queensland (No 2),[146] saw the High Court of Australia reject the idea of terra nullius. This rejection ended up recognizing that there was a pre-existing system of law practised by the Meriam people.

A 2009 United Nations publication says:[31]

Although indigenous peoples are often portrayed as a hindrance to development, their cultures and traditional knowledge are also increasingly seen as assets. It is argued that it is important for the human species as a whole to preserve as wide a range of cultural diversity as possible, and that the protection of indigenous cultures is vital to this enterprise.

Human rights violations

The Bangladesh Government has stated that there are "no indigenous peoples in Bangladesh".[147] This has angered the indigenous peoples of Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh, collectively known as the Jumma.[148] Experts have protested against this move of the Bangladesh Government and have questioned the Government's definition of the term "indigenous peoples".[149][150] This move by the Bangladesh Government is seen by the indigenous peoples of Bangladesh as another step by the Government to further erode their already limited rights.[151]

Hindus and Chams have both experienced religious and ethnic persecution and restrictions on their faith under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confiscating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus. In 2010 and 2013 several incidents occurred in Thành Tín and Phươc Nhơn villages where Cham were murdered by Vietnamese. In 2012, Vietnamese police in Chau Giang village stormed into a Cham Mosque, stole the electric generator, and also raped Cham girls.[152] Cham in the Mekong Delta have also been economically marginalised, with ethnic Vietnamese settling on land previously owned by Cham people with state support.[153]

The Indonesian government has outright denied the existence of indigenous peoples within the countries' borders. In 2012, Indonesia stated that ‘The Government of Indonesia supports the promotion and protection of indigenous people worldwide ... Indonesia, however, does not recognize the application of the indigenous peoples concept ... in the country'.[154] Along with the brutal treatment of the country's Papuan people (a conservative estimate places the violent deaths at 100,000 people in West New Guinea since Indonesian occupation in 1963, see Papua Conflict) has led to Survival International condemning Indonesia for treating its indigenous peoples as the worst in the world.[154]

The Vietnamese viewed and dealt with the indigenous Montagnards from the Central Highlands of Vietnam as "savages", which caused a Montagnard uprising against the Vietnamese.[155] The Vietnamese were originally centered around the Red River Delta but engaged in conquest and seized new lands such as Champa, the Mekong Delta (from Cambodia) and the Central Highlands during Nam Tien. While the Vietnamese received strong Chinese influence in their culture and civilization and were Sinicized, and the Cambodians and Laotians were Indianized, the Montagnards in the Central Highlands maintained their own indigenous culture without adopting external culture and were the true indigenous of the region. To hinder encroachment on the Central Highlands by Vietnamese nationalists, the term Pays Montagnard du Sud-Indochinois (PMSI) emerged for the Central Highlands along with the indigenous being addressed by the name Montagnard.[156] The tremendous scale of Vietnamese Kinh colonists flooding into the Central Highlands has significantly altered the demographics of the region.[157] The anti-ethnic minority discriminatory policies by the Vietnamese, environmental degradation, deprivation of lands from the indigenous people, and settlement of indigenous lands by an overwhelming number of Vietnamese settlers led to massive protests and demonstrations by the Central Highland's indigenous ethnic minorities against the Vietnamese in January–February 2001. This event gave a tremendous blow to the claim often published by the Vietnamese government that in Vietnam "There has been no ethnic confrontation, no religious war, no ethnic conflict. And no elimination of one culture by another."[158]

In May 2016, the Fifteenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) affirmed that indigenous peoples are distinctive groups protected in international or national legislation as having a set of specific rights based on their linguistic and historical ties to a particular territory, prior to later settlement, development, and or occupation of a region.[159] The session affirms that, since indigenous peoples are vulnerable to exploitation, marginalization, oppression, forced assimilation, and genocide by nation states formed from colonizing populations or by different, politically dominant ethnic groups, individuals and communities maintaining ways of life indigenous to their regions are entitled to special protection.

The indigenous people from Tanzania’s Maasai community were reportedly subjected to eviction from their ancestral land to make way for a luxury game reserve by Otterlo Business Corporation in June 2022. The game reserve was reportedly being set up for the royals of the United Arab Emirates also linked to OBC or the Otterlo Business Corporation. According to lawyers and human rights groups and activists, approximately 30 Maasai people were injured by security forces in the process of eviction and delimiting a land area of 1500 km2. A 2019 UN report has described OBC as a ‘UAE-based’ luxury-game hunting company, granted a license to hunt by the Tanzanian government in 1992 for “the UAE royal family to organize private hunting trips”, denying the Maasai people access to their own land.[160]

Health issues

In December 1993, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the International Decade of the World's Indigenous People, and requested UN specialized agencies to consider with governments and indigenous people how they can contribute to the success of the Decade of Indigenous People, commencing in December 1994. As a consequence, the World Health Organization, at its Forty-seventh World Health Assembly, established a core advisory group of indigenous representatives with special knowledge of the health needs and resources of their communities, thus beginning a long-term commitment to the issue of the health of indigenous peoples.[161]

The WHO notes that "Statistical data on the health status of indigenous peoples is scarce. This is especially notable for indigenous peoples in Africa, Asia and eastern Europe," but snapshots from various countries (where such statistics are available) show that indigenous people are in worse health than the general population, in advanced and developing countries alike: higher incidence of diabetes in some regions of Australia;[162] higher prevalence of poor sanitation and lack of safe water among Twa households in Rwanda;[163] a greater prevalence of childbirths without prenatal care among ethnic minorities in Vietnam;[164] suicide rates among Inuit youth in Canada are eleven times higher than the national average;[165] infant mortality rates are higher for Indigenous peoples everywhere.[166]

The first UN publication on the State of the World's Indigenous Peoples revealed alarming statistics about indigenous peoples' health. Health disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous populations are evident in both developed and developing countries. Native Americans in the United States are 600 times more likely to acquire tuberculosis and 62% more likely to commit suicide than the non-Indian population. Tuberculosis, obesity, and type 2 diabetes are major health concerns for the indigenous in developed countries.[167] Globally, health disparities touch upon nearly every health issue, including HIV/AIDS, cancer, malaria, cardiovascular disease, malnutrition, parasitic infections, and respiratory diseases, affecting indigenous peoples at much higher rates. Many causes of indigenous children's mortality could be prevented. Poorer health conditions amongst indigenous peoples result from longstanding societal issues, such as extreme poverty and racism, but also the intentional marginalization and dispossession of indigenous peoples by dominant, non-indigenous populations and societal structures.[167]

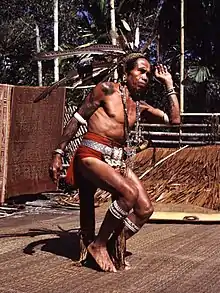

Racism and discrimination

Indigenous peoples have frequently been subjected to various forms of racism and discrimination. Indigenous peoples have been denoted primitives, savages[168] or uncivilized. These terms occurred commonly during the heyday of European colonial expansion, but still continue in use in certain societies in modern times.[169]

During the 17th century, Europeans commonly labeled indigenous peoples as "uncivilized". Some philosophers, such as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), considered indigenous people to be merely "savages". Others (especially literary figures in the 18th century) popularised the concept of "noble savages". Those who were close to the Hobbesian view tended to believe themselves to have a duty to "civilize" and "modernize" the indigenous. Although anthropologists, especially from Europe, used to apply these terms to all tribal cultures, the practice has fallen into disfavor as demeaning and is, according to many anthropologists, not only inaccurate, but dangerous.

Survival International runs a campaign to stamp out media portrayal of indigenous peoples as "primitive" or "savages".[170] Friends of Peoples Close to Nature considers not only that indigenous culture should be respected as not being inferior, but also sees indigenous ways of life as offering frameworks in sustainability and as a part of the struggle within the "corrupted" western world, from which the threat stems.[171]

After World War I (1914-1918), many Europeans came to doubt the morality of the means used to "civilize" peoples. At the same time, the anti-colonial movement, and advocates of indigenous peoples, argued that words such as "civilized" and "savage" were products and tools of colonialism, and argued that colonialism itself was savagely destructive. In the mid-20th century, European attitudes began to shift to the view that indigenous and tribal peoples should have the right to decide for themselves what should happen to their ancient cultures and ancestral lands.[172]

Cultural appropriation

The cultures of indigenous peoples provides appeal for New Age advocates seeking to find ancient traditional truths, spiritualities and practices to appropriate into their worldviews.[173]

Environmental injustice

At an international level, indigenous peoples have received increased recognition of their environmental rights since 2002, but few countries respect these rights in reality. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the General Assembly in 2007, established indigenous peoples' right to self-determination, implying several rights regarding natural resource management. In countries where these rights are recognized, land titling and demarcation procedures are often put on delay, or leased out by the state as concessions for extractive industries without consulting indigenous communities.[167]

Many in the United States federal government are in favor of exploiting oil reserves in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where the Gwich'in indigenous people rely on herds of caribou. Oil drilling could destroy thousands of years of culture for the Gwich'in. On the other hand, some of the Inupiat Eskimo, another indigenous community in the region, favor oil drilling because they could benefit economically.[175]

The introduction of industrial agricultural technologies such as fertilizers, pesticides, and large plantation schemes have destroyed ecosystems that indigenous communities formerly depended on, forcing resettlement. Development projects such as dam construction, pipelines and resource extraction have displaced large numbers of indigenous peoples, often without providing compensation. Governments have forced indigenous peoples off of their ancestral lands in the name of ecotourism and national park development. Indigenous women are especially affected by land dispossession because they must walk longer distances for water and fuel wood. These women also become economically dependent on men when they lose their livelihoods. Indigenous groups asserting their rights has most often resulted in torture, imprisonment, or death.[167]

The building of dams can hurt indigenous peoples by hurting the ecosystems that provide them water, food. For example, the Munduruku people in the Amazon rainforest are opposing the building of Tapajós dam[176] with the help of Greenpeace.[177]

Most indigenous populations are already subject to the deleterious effects of climate change. Climate change has not only environmental, but also human rights and socioeconomic implications for indigenous communities. The World Bank acknowledges climate change as an obstacle to Millennium Development Goals, notably the fight against poverty, disease, and child mortality, in addition to environmental sustainability.[167]

Use of indigenous knowledge

Indigenous knowledge is considered as very important for issues linked with sustainability.[178][179] Professor Martin Nakata is a pioneer in the field of bringing indigenous knowledge to mainstream academics and media through digital documentation of unique contributions by aboriginal people.[180]

The World Economic Forum supports using indigenous knowledge and giving to the indigenous peoples ownership of their land for protecting nature.[181]

Knowledge reconstruction

The Western and Eastern Penan are two major groups of indigenous populations in Malaysia. The Eastern Penan are famous for their resistance to loggers threatening their natural resources, specifically Sago palms and various fruit bearing trees. Because of the Penan's international fame, environmentalists often visited the area to document such happenings and learn more about and from the people there, including their perspective on the land's invasion. Environmentalists such as Davis and Henley, lacking dialectical connections needed to deeply understand the Penan, additionally lacked full knowledge of the situation's specific weight to the indigenous peoples.

On a good intent, the two embarked on a mission to propagate conservation of the Penan's land resources, and mostly likely feeling a deep but inexpressible richness in the people's traditions, Davis and Henley were among the many who reconstructed indigenous knowledge into fitting a Western narrative and agenda. For example, Davis and Henley romanticized and misconstrued the traditional Penan concept of molong, meaning: to preserve. Brosius observed this concept as the Penan marked trees for personal use and to preserve them for future harvesting of fruits or for materials.[182] Davis and Henley made inferences beyond the truth of this tradition in their accounts while also lumping all native groups of Malaysia into one homogeneous group with the same ideas and traditions. In other words, they made no distinction between the Eastern and Western Penan in their descriptions.

Another common occurrence is to extend indigenous knowledge beyond its limits and into spiritually profound and sacredness. This tendency of journalists extends beyond Davis and Henley. It serves non-natives to add a narrative and value beyond that which already exists within the knowledge base of indigenous peoples, while also bridging many various gaps in understanding not understood otherwise. Not only do these false recounts of indigenous knowledge and traditions skew the beliefs of onlookers, but they also reconstruct the idea native peoples have of their own traditions by erasing its original value system and replacing it with a westernized version.[182]

See also

- Collective rights

- Colonialism

- Cultural appropriation

- Ethnic minority

- Ecotourism's impact on Indigenous people and Indigenous lands

- Genocide of Indigenous peoples

- Human rights

- The Image Expedition

- Indigenism

- Indigenous Futurisms

- Indigenous intellectual property

- Indigenous Peoples Climate Change Assessment Initiative

- Indigenous rights

- Intangible cultural heritage

- International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples

- National Indigenous Peoples Day in Canada

- Indigenous Peoples' Day in the US

- Isuma

- List of active non-governmental organizations of national minorities, Indigenous and diasporas

- List of ethnic groups

- List of Indigenous peoples

- Missing and murdered Indigenous women

- Uncontacted peoples

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

- Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization

- Virgin soil epidemic

Notes

- also referred to as First peoples, First nations, Aboriginal peoples, Native peoples, Indigenous natives, or Autochthonous peoples These terms are often capitalized when referring to specific indigenous peoples as ethnic groups, nations, and the members of these groups.[1][2][3]

References

- "APA Style - Racial and Ethnic Identity". Section 5.7 of the APA Publication Manual, Seventh Edition. Associated Press. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

Racial and ethnic groups are designated by proper nouns and are capitalized. ... capitalize terms such as “Native American,” “Hispanic,” and so on. Capitalize “Indigenous” and “Aboriginal” whenever they are used. Capitalize “Indigenous People” or “Aboriginal People” when referring to a specific group (e.g., the Indigenous Peoples of Canada), but use lowercase for “people” when describing persons who are Indigenous or Aboriginal (e.g., “the authors were all Indigenous people but belonged to different nations”

- "Reporter's Indigenous Terminology Guide". The Native American Journalists Association. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "NAJA AP Style Guide". The Native American Journalists Association. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Indigenous definition". Merriam-Webster. 2021.

- Mathewson, Kent (2004). "Drugs, Moral Geographies, and Indigenous Peoples: Some Initial Mappings and Central Issues". Dangerous Harvest: Drug Plants and the Transformation of Indigenous Landscapes. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-514319-5.

As Sir Thomas Browne remarked in 1646, (this seems to be the first usage in its modern sense).

- Browne, Sir Thomas (1646). "Pseudodoxia Epidemica, Chap. X. Of the Blackness of Negroes". University of Chicago. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- "Who are the indigenous and tribal peoples?". www.ilo.org. 22 July 2016.

- Acharya, Deepak and Shrivastava Anshu (2008): Indigenous Herbal Medicines: Tribal Formulations and Traditional Herbal Practices, Aavishkar Publishers Distributor, Jaipur, India. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7. p. 440

- LaDuke, Winona (1997). "Voices from White Earth: Gaa-waabaabiganikaag". People, Land, and Community: Collected E.F. Schumacher Society Lectures. Yale University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-300-07173-3.

- Miller, Robert J.; Ruru, Jacinta; Behrendt, Larissa; Lindberg, Tracey (2010). Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies. OUP Oxford. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-0-19-957981-5.

- Taylor Saito, Natsu (2020). "Unsettling Narratives". Settler Colonialism, Race, and the Law: Why Structural Racism Persist (eBook). NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-0802-6.

...several thousand nations have been arbitrarly (and generally involuntarily) incorporated into approximately two hundred political constructs we call independent states...

- Sanders, Douglas (1999). "Indigenous peoples: Issues of definition". International Journal of Cultural Property. 8: 4–13. doi:10.1017/S0940739199770591. S2CID 154898887.

- Bodley 2008:2

- Muckle, >:>Robert J. (2012). Indigenous Peoples of North America: A Concise Anthropological Overview. University of Toronto Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4426-0416-2.

- McIntosh, Ian (September 2000). "Are there Indigenous Peoples in Asia?". Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine.

- "indigene, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Web. 22 November 2016.

- "indigenous (adj.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Peters, Michael A.; Mika, Carl T. (10 November 2017). "Aborigine, Indian, indigenous or first nations?". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 49 (13): 1229–1234. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1279879. ISSN 0013-1857.

- "autochthonous". Wordsmith.org. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012). Decolonizing methodologies : research and indigenous peoples (Second ed.). Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press. ISBN 978-1-877578-28-1. OCLC 805707083.

- Robert K. Hitchcock, Diana Vinding, Indigenous Peoples' Rights in Southern Africa, IWGIA, 2004, p. 8 based on Working Paper by the Chairperson-Rapporteur, Mrs. Erica-Irene A. Daes, on the concept of indigenous people. UN-Dokument E/CN.4/Sub.2/AC.4/1996/2 (, unhchr.ch)

- S. James Anaya, Indigenous Peoples in International Law, 2nd ed., Oxford University press, 2004, p. 3; Professor Anaya teaches Native American Law, and is the third Commission on Human Rights Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People

- Martínez-Cobo (1986/7), paras. 379–82,

- "Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands and Natural Resources". cidh.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Cunha, Manuela Carneiro da; de Almeida, Mauro W. B. (2000). "Indigenous People, Traditional People, and Conservation in the Amazon". Daedalus. 129 (2): 315–338. ISSN 0011-5266. JSTOR 20027639.

- "Indigenous Peoples". World Bank. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples - 9 August". www.un.org. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Study of the Problem of Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations, p. 10, Paragraph 25, 30 July 1981, UN EASC

- "A working definition, by José Martinez Cobo". IWGIA - International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, p. 1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010.

- State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, Secretariat of Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, UN, 2009 Archived 15 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. pg. 1-2.

- "Indigenous populations". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

-

Anaya, S. James (2004) [1996]. "Developments within the Modern Era of Human Rights". Indigenous Peoples in International Law (2 (revised) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780195173505. Retrieved 26 October 2022.