Institutional racism

Institutional racism, also known as systemic racism, is a form of racism that is embedded in the laws and regulations of a society or an organization. It manifests as discrimination in areas such as criminal justice, employment, housing, health care, education, and political representation.[1]

The term institutional racism was first coined in 1967 by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation.[2] Carmichael and Hamilton wrote in 1967 that while individual racism is often identifiable because of its overt nature, institutional racism is less perceptible because of its "less overt, far more subtle" nature. Institutional racism "originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society, and thus receives far less public condemnation than [individual racism]".[3]

Institutional racism was defined by Sir William Macpherson in the UK's Lawrence report (1999) as: "The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin". It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour that amount to discrimination through prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness, and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people."[4][5]

Classification

.jpg.webp)

In the past, the term "racism" was often used interchangeably with "prejudice," forming an opinion of another person based on incomplete information. In the last quarter of the 20th Century, racism became associated with systems rather than individuals. In 1977, David Wellman in his book Portraits of White Racism, defined racism as "a system of advantage based on race," illustrating this definition through countless examples of white people supporting racist institutions while denying that they are prejudiced. White people can be nice to people of color while continuing to uphold systemic racism that benefits them, such as lending practices, well-funded schools, and job opportunities.[6] The concept of institutional racism re-emerged in political discourse in the mid and late 1990s, but has remained a contested concept.[7] Institutional racism is where race causes a different level of access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society.[8]

Professor James M. Jones theorised three major types of racism: personally mediated, internalized, and institutionalized.[9] Personally mediated racism includes the deliberate specific social attitudes to racially prejudiced action (bigoted differential assumptions about abilities, motives, and the intentions of others according to their race), discrimination (the differential actions and behaviours towards others according to their race), stereotyping, commission, and omission (disrespect, suspicion, devaluation, and dehumanization). Internalized racism is the acceptance, by members of the racially stigmatized people, of negative perceptions about their own abilities and intrinsic worth, characterized by low self-esteem, and low esteem of others like them. This racism can be manifested through embracing "whiteness" (e.g. stratification by skin colour in non-white communities), self-devaluation (e.g., racial slurs, nicknames, rejection of ancestral culture, etc.), and resignation, helplessness, and hopelessness (e.g., dropping out of school, failing to vote, engaging in health-risk practices, etc.).[10]

Persistent negative stereotypes fuel institutional racism, and influence interpersonal relations. Racial stereotyping contributes to patterns of racial residential segregation and redlining, and shapes views about crime, crime policy, and welfare policy, especially if the contextual information is stereotype-consistent.[11]

Institutional racism is distinguished from racial bigotry by the existence of systemic, institutionalized policies, practices and economic and political structures that place minority racial and ethnic groups at a disadvantage in relation to an institution's racial or ethnic majority. One example of the difference is public school budgets in the U.S. (including local levies and bonds) and the quality of teachers, which are often correlated with property values: rich neighborhoods are more likely to be more "white" and to have better teachers and more money for education, even in public schools. Restrictive housing contracts and bank lending policies have also been listed as forms of institutional racism.

Other examples sometimes described as institutional racism are racial profiling by security guards and police,[12] use of stereotyped racial caricatures, the under- and misrepresentation of certain racial groups in the mass media, and race-based barriers to gainful employment and professional advancement. Additionally, differential access to goods, services, and opportunities of society can be included within the term "institutional racism", such as unpaved streets and roads, inherited socio-economic disadvantage, and standardized tests (each ethnic group prepared for it differently; many are poorly prepared).[13]

Some sociological[14] investigators distinguish between institutional racism and "structural racism" (sometimes referred to as "structured racialization").[15] The former focuses upon the norms and practices within an institution, the latter upon the interactions among institutions, interactions that produce racialized outcomes against non-white people.[16] An important feature of structural racism is that it cannot be reduced to individual prejudice or to the single function of an institution.[17]

Algeria

.jpg.webp)

The French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) supported colonization in general, particularly the colonization of Algeria. In several speeches on France's foreign affairs and in two official reports presented to the National Assembly in March 1847 on behalf of an ad hoc commission, he also repeatedly commented on and analyzed the issue in his voluminous correspondence. In short, Tocqueville developed a theoretical basis for French expansion in North Africa.[18] He even studied the Koran, sharply concluding that Islam was "the main cause of the decadence... of the Muslim world". His opinions are also instructive about the early years of the French conquest and how the colonial state was first set up and organized. Tocqueville emerged as an early advocate of "total domination" in Algeria and subsequent "devastation of the country".[19]

On 31 January 1830, Charles X capturing Algiers made the French state thus begin what became institutional racism directed at the Kabyle, or Berbers, of Arab descent in north Africa. The Dey of Algiers had insulted the monarchy by slapping the French ambassador with a fly whisk, and the French used that pretext to invade and to put an end to piracy in the vicinity. The unofficial objective was to restore the prestige of the French crown and gain a foothold in North Africa, thereby preventing the British gaining advantage over France in the Mediterranean. The July Monarchy, which came to power in 1830, inherited that burden. The next ten years saw the indigenous population subjected to the might of the French army. By 1840, more conservative elements gained control of the government and dispatched General Thomas Bugeaud, the newly appointed governor of the colony, to Algeria, which marked the real start of the country's conquest. The methods employed were atrocious; the army deported villagers en masse, massacred the men and raped the women, took the children hostage, stole livestock and harvests and destroyed orchards. Tocqueville wrote, "I believe the laws of war entitle us to ravage the country and that we must do this, either by destroying crops at harvest time, or all the time by making rapid incursions, known as raids, the aim of which is to carry off men and flocks."[20]

Tocqueville added: "In France I have often heard people I respect, but do not approve, deplore [the army] burning harvests, emptying granaries and seizing unarmed men, women and children. As I see it, these are unfortunate necessities that any people wishing to make war on the Arabs must accept."[21] He also advocated that "all political freedoms must be suspended in Algeria".[22] Marshal Bugeaud, who was the first governor-general and also headed the civil government, was rewarded by the King for the conquest and having instituted the systemic use of torture, and following a "scorched earth" policy against the Arab population.

Land grab

Once the conquest of Algiers was accomplished soldier-politician Bertrand Clauzel and others formed a company to acquire agricultural land and, despite official discouragement, to subsidise its settlement by European farmers, which triggered a land rush. He became governor general in 1835 and used his office to make private investments in land by encouraging bureaucrats and army officers in his administration to do the same. The development created a vested interest in government officials for greater French involvement in Algeria. Merchants with influence in the government also saw profit in land speculation, which resulted in expanding the French occupation. Large agricultural tracts were carved out, and factories and businesses began exploiting cheap local labour and also benefited from laws and edicts that gave control to the French. The policy of limited occupation was formally abandoned in 1840 and replaced by one of complete control. By 1843, Tocqueville intended to protect and extend expropriation by the rule of law and so advocated setting up special courts, which were based on what he called "summary" procedure, to carry out a massive expropriation for the benefit of French and other European settlers, who could thus purchase land at attractive prices and live in villages, which the colonial government had equipped with fortifications, churches, schools and even fountains. His belief, which framed his writings and influenced state actions, was that the local people, who had been driven out by the army and robbed of their land by the judges, would gradually die out.[23]

The French colonial state, as he conceived it and as it took shape in Algeria, was a two-tiered organization, quite unlike the regime in Mainland France. It introduced two different political and legal systems that were based on racial, cultural and religious distinctions. According to Tocqueville, the system that should apply to the Colons would enable them alone to hold property and travel freely but would deprive them of any form of political freedom, which should be suspended in Algeria. "There should therefore be two quite distinct legislations in Africa, for there are two very separate communities. There is absolutely nothing to prevent us treating Europeans as if they were on their own, as the rules established for them will only ever apply to them".[24]

Following the defeats of the resistance in the 1840s, colonisation continued apace. By 1848, Algeria was populated by 109,400 Europeans, only 42,274 of whom were French.[25] The leader of the Colons delegation, Auguste Warnier (1810–1875), succeeded in the 1870s in modifying or introducing legislation to facilitate the private transfer of land to settlers and continue Algeria's appropriation of land from the local population and distribution to settlers. Europeans held about 30% of the total arable land, including the bulk of the most fertile land and most of the areas under irrigation.[26] In 1881, the Code de l'Indigénat made the discrimination official by creating specific penalties for indigenes and by organising the seizure or appropriation of their lands.[27] By 1900, Europeans produced more than two-thirds of the value of output in agriculture and practically all of the agricultural exports. The colonial government imposed more and higher taxes on Muslims than on Europeans.[28] The Muslims, in addition to paying traditional taxes dating from before the French conquest, also paid new taxes from which the Colons were normally exempted. In 1909, for instance, Muslims, who made up almost 90% of the population but produced 20% of Algeria's income, paid 70% of direct taxes and 45% of the total taxes collected. Also, Colons controlled how the revenues would be spent and so their towns had handsome municipal buildings, paved streets lined with trees, fountains and statues, but Algerian villages and rural areas benefited little, if at all, from tax revenues.[29]

In education

The colonial regime proved severely detrimental to overall education for Muslims, who had previously relied on religious schools to learn reading, writing, and religion. The state appropriated the habus lands, the religious foundations that constituted the main source of income for religious institutions, including schools, in 1843, but colonial officials refused to allocate enough money to maintain schools and mosques properly and to provide for enough teachers and religious leaders for the growing population. In 1892, more than five times as much was spent for the education of Europeans as for Muslims, who had five times as many children of school age. Because few Muslim teachers were trained, Muslim schools were largely staffed by French teachers. Even a state-operated madrasa often had French faculty members. Attempts to institute bilingual, bicultural schools, intended to bring Muslim and European children together in the classroom, were a conspicuous failure, which were rejected by both communities and phased out after 1870. According to one estimate, fewer than 5% of Algerian children attended any kind of school in 1870. As late as 1954, only one Muslim boy in five and one girl in sixteen received formal schooling.[30] Efforts were begun by 1890 to educate a small number of Muslims along with European students in the French school system as part of France's "civilising mission" in Algeria. The curriculum was entirely French and allowed no place for Arabic studies, which were deliberately downgraded even in Muslim schools. Within a generation, a class of well-educated, gallicized Muslims, the évolués (literally "evolved ones"), had been created.

Enfranchisement

Following its conquest of Ottoman Algeria in 1830, France maintained for well over a century its colonial rule in the territory that has been described as "quasi-apartheid".[31] The colonial law of 1865 allowed Arab and Berber Algerians to apply for French citizenship only if they abandoned their Muslim identity; Azzedine Haddour argues that it established "the formal structures of a political apartheid".[32] Camille Bonora-Waisman writes, "In contrast with the Moroccan and Tunisian protectorates", the "colonial apartheid society" was unique to Algeria.[33]

Under the French Fourth Republic, Muslim Algerians were accorded the rights of citizenship, but the system of discrimination was maintained in more informal ways. Frederick Cooper writes that Muslim Algerians "were still marginalized in their own territory, notably the separate voter roles of 'French' civil status and of 'Muslim' civil status, to keep their hands on power."[33] The "internal system of apartheid" was met with considerable resistance by the Algerian Muslims affected by it, and it is cited as one of the causes of the 1954 insurrection.

There was clearly nothing exceptional about the crimes committed by the French army and state in Algeria in 1955 to 1962. On the contrary, they were part of history repeating itself.[34]

State racism

Following the views of Michel Foucault, the French historian Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison spoke of a "state racism" under the French Third Republic, a notable example being the 1881 Indigenous Code applied in Algeria. Replying to the question "Isn't it excessive to talk about a state racism under the Third Republic?", he replied:

"No, if we can recognize 'state racism' as the vote and implementation of discriminatory measures, grounded on a combination of racial, religious and cultural criteria, in those territories. The 1881 Indigenous Code is a monument of this genre! Considered by contemporary prestigious jurists as a 'juridical monstruosity', this code[35] planned special offenses and penalties for 'Arabs'. It was then extended to other territories of the empire. On one hand, a state of rule of law for a minority of French and Europeans located in the colonies. On the other hand, a permanent state of exception for the "indigenous" people. This situation lasted until 1945".[36]

During a reform effort in 1947, the French created a bicameral legislature with one house for French citizens and another for Muslims, but it made a European's vote worth seven times a Muslim's vote.[37] Even the events of 1961 show that France had not changed its treatment of the Algerians over the years, as the police took up the institutional racism that the French state had made law in its treatment of Arabs who, as Frenchmen, had moved to Mainland France.[38]

| Paris massacre of 1961 | |

|---|---|

| Part of Algerian war | |

| Deaths | 40/200+ |

| Victims | a demonstration of some 30,000 pro-National Liberation Front (FLN) Algerians |

| Perpetrators | Head of the Parisian police, Maurice Papon, the French National Police |

Further reading

- Original text: Library of Congress Country Study of Algeria

- Aussaresses, Paul. The Battle of the Casbah: Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in Algeria, 1955–1957. (New York: Enigma Books, 2010) ISBN 978-1-929631-30-8.

- Bennoune, Mahfoud. The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830–1987 (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- Gallois, William. A History of Violence in the Early Algerian Colony (2013), On French violence 1830–1847 online review

- Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962, (Viking Adult, 1978)

- Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina

- The Battle of Algiers

- The 1961 massacre was referenced in Caché, a 2005 film by Michael Haneke.

- The 2005 French television drama-documentary Nuit noire, 17 octobre 1961 explores in detail the events of the massacre. It follows the lives of several people and also shows some of the divisions within the Paris police, with some openly arguing for more violence while others tried to uphold the rule of law.

- Drowning by Bullets, a television documentary in the British Secret History series, first shown on 13 July 1992.

Australia

It is estimated that the population of Aboriginal peoples prior to the European colonisation of Australia (starting in 1788) was about 314,000.[39] It has also been estimated by ecologists that the land could have supported a population of a million people. By 1901 they had been reduced by two-thirds to 93,000. In 2011 Indigenous Australians (comprising both Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander people) comprised about 3% of the total population, at 661,000. When Captain Cook landed in Botany Bay in 1770, he was under orders not to plant the British flag and to defer to any native population, which was largely ignored.[40]

Land rights, stolen generations, and terra nullius

Torres Strait Islander people are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands, which are in the Torres Strait between the northernmost tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea. Institutional racism had its early roots here due to interactions between these islanders, who had Melanesian origins and depended on the sea for sustenance and whose land rights were abrogated, and later the Australian Aboriginal peoples, whose children were removed from their families by Australian Federal and State government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments.[41] The removals occurred in the period between approximately 1909 and 1969, resulting in what later became known as the Stolen Generations. An example of the abandonment of mixed-race ("half-caste") children in the 1920s is given in a report by Walter Baldwin Spencer that many mixed-descent children born during construction of The Ghan railway were abandoned at early ages with no one to provide for them. This incident and others spurred the need for state action to provide for and protect such children.[42] Both were official policy and were coded into law by various acts. They have both been rescinded and restitution for past wrongs addressed at the highest levels of government.

The treatment of the Indigenous people by the colonisers has been termed cultural genocide.[43] The earliest introduction of child removal to legislation is recorded in the Victorian Aboriginal Protection Act 1869.[44] The Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines had been advocating such powers since 1860, and the passage of the Act gave the colony of Victoria a wide suite of powers over Aboriginal and "half-caste" persons, including the forcible removal of children,[45] especially "at risk" girls.[46] By 1950, similar policies and legislation had been adopted by other states and territories, such as the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld),[47] the Aborigines Ordinance 1918 (NT),[48] the Aborigines Act 1934 (SA)[49] and the 1936 Native Administration Act (WA).

The child removal legislation resulted in widespread removal of children from their parents and exercise of sundry guardianship powers by Protectors of Aborigines up to the age of 16 or 21. Policemen or other agents of the state were given the power to locate and transfer babies and children of mixed descent from their mothers or families or communities into institutions.[50] In these Australian states and territories, half-caste institutions (both government Aboriginal reserves and church-run mission stations) were established in the early decades of the 20th century for the reception of these separated children. Examples of such institutions include Moore River Native Settlement in Western Australia, Doomadgee Aboriginal Mission in Queensland, Ebenezer Mission in Victoria and Wellington Valley Mission in New South Wales.

In 1911, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in South Australia, William Garnet South, reportedly "lobbied for the power to remove Aboriginal children without a court hearing because the courts sometimes refused to accept that the children were neglected or destitute". South argued that "all children of mixed descent should be treated as neglected". His lobbying reportedly played a part in the enactment of the Aborigines Act 1911; this made him the legal guardian of every Aboriginal child in South Australia, including so-called "half-castes". Bringing Them Home,[51] a report on the status of the mixed race stated "... the physical infrastructure of missions, government institutions and children's homes was often very poor and resources were insufficient to improve them or to keep the children adequately clothed, fed, and sheltered".

In reality, during this period removal of the mixed-race children was related to the fact that most were offspring of domestic servants working on pastoral farms,[52] and their removal allowed the mothers to continue working as help on the farm while at the same time removing the whites from responsibility for fathering them and from social stigma for having mixed-race children visible in the home.[53] Also, when they were left alone on the farm they became targets of the men who contributed to the rise in the population of mixed-race children.[54] The institutional racism was government policy gone awry, one that allowed babies to be taken from their mothers at birth, and this continued for most of the 20th century. That it was policy and kept secret for over 60 years is a mystery that no agency has solved to date.[55]

In the 1930s, the Northern Territory Protector of Natives, Cecil Cook, perceived the continuing rise in numbers of "half-caste" children as a problem. His proposed solution was: "Generally by the fifth and invariably by the sixth generation, all native characteristics of the Australian Aborigine are eradicated. The problem of our half-castes will quickly be eliminated by the complete disappearance of the black race, and the swift submergence of their progeny in the white". He did suggest at one point that they be all sterilised.[56]

Similarly, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, A. O. Neville, wrote in an article for The West Australian in 1930: "Eliminate in future the full-blood and the white and one common blend will remain. Eliminate the full-blood and permit the white admixture and eventually, the race will become white".[57]

Official policy then concentrated on removing all Black people from the population,[58] to the extent that the full-blooded Aboriginal people were hunted to extinguish them from society,[59] and those of mixed race would be assimilated with the white race so that in a few generations they too would become white.[60]

By 1900 the recorded Indigenous Australian population had declined to approximately 93,000.

Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the electoral rolls. The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except for New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901.[61]

Land rights returned

In 1981 a land rights conference was held at James Cook University, where Eddie Mabo,[62] a Torres Strait Islander, made a speech to the audience in which he explained the land inheritance system on Murray Island.[63] The significance of this in terms of Australian common law doctrine was taken note of by one of the attendees, a lawyer, who suggested there should be a test case to claim land rights through the court system.[64] Ten years later, five months after Eddie Mabo died, on 3 June 1992, the High Court announced its historic decision, namely overturning the legal doctrine of terra nullius, which was the term applied by the British relating to the continent of Australia – "empty land".[65]

Public interest in the Mabo case had the side effect of throwing the media spotlight on all issues related to Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia, and most notably the Stolen Generations. The social impacts of forced removal have been measured and found to be quite severe. Although the stated aim of the "resocialisation" program was to improve the integration of Aboriginal people into modern society, a study conducted in Melbourne and cited in the official report found that there was no tangible improvement in the social position of "removed" Aboriginal people as compared to "non-removed", particularly in the areas of employment and post-secondary education.[66]

Most notably, the study indicated that removed Aboriginal people were actually less likely to have completed a secondary education, three times as likely to have acquired a police record and were twice as likely to use illicit drugs.[67] The only notable advantage "removed" Aboriginal people possessed was a higher average income, which the report noted was most likely due to the increased urbanisation of removed individuals, and hence greater access to welfare payments than for Aboriginal people living in remote communities.[68]

Indigenous health and employment

In his 2008 address to the houses of parliament apologising for the treatment of the Indigenous population, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a plea to the health services regarding the disparate treatment in health services. He noted the widening gap between the treatment of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and committed the government to a strategy called "Closing the Gap", admitting to past institutional racism in health services that shortened the life expectancy of the Aboriginal people. Committees that followed up on this outlined broad categories to redress the inequities in life expectancy, educational opportunities and employment.[69] The Australian government also allocated funding to redress the past discrimination. Indigenous Australians visit their general practitioners (GPs) and are hospitalised for diabetes, circulatory disease, musculoskeletal conditions, respiratory and kidney disease, mental, ear and eye problems and behavioural problems yet are less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to visit the GP, use a private doctor, or apply for residence in an old age facility. Childhood mortality rates, the gap in educational achievement and lack of employment opportunities were made goals that in a generation should halve the gap. A national "Close the Gap" day was announced for March of each year by the Human Rights Commission.[70]

In 2011, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that life expectancy had increased since 2008 by 11.5 years for women and 9.7 years for men along with a significant decrease in infant mortality, but it was still 2.5 times higher than for the non-indigenous population. Much of the health woes of the Indigenous people could be traced to the availability of transport. In remote communities, the report cited 71% of the population in those remote Indigenous communities lacked access to public transport, and 78% of the communities were more than 80 kilometres (50 miles) from the nearest hospital. Although English was the official language of Australia, many Indigenous Australians did not speak it as a primary language, and the lack of printed materials that were translated into the Australian Aboriginal languages and the non-availability of translators formed a barrier to adequate health care for Aboriginal people. By 2015, most of the funding promised to achieve the goals of "Closing the Gap" had been cut, and the national group[71] monitoring the conditions of the Indigenous population was not optimistic that the promises of 2008 will be kept.[72] In 2012, the group complained that institutional racism and overt discrimination continued to be issues, and that, in some sectors of government, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was being treated as an aspirational rather that a binding document.[73]

Canada

Indigenous Canadians

The living standard of indigenous peoples in Canada falls far short of those of the non-indigenous, and they, along with other 'visible minorities' remain, as a group, the poorest in Canada.[16][74] There continue to be barriers to gaining equality with other Canadians of European ancestry. The life expectancy of First Nations people is lower; they have fewer high school graduates, much higher unemployment rates, nearly double the number of infant deaths and significantly greater contact with law enforcement. Their incomes are lower, they enjoy fewer promotions in the workplace and as a group, the younger members are more likely to work reduced hours or weeks each year.[74]

Many in Europe during the 19th century (as reflected in the Imperial Report of the Select Committee on Aborigines),[75] supported the goal put forth by colonial imperialists of 'civilizing' the Native populations. This led to an emphasis on the acquisition of Aboriginal lands in exchange for the putative benefits of European society and their associated Christian religions. British control of Canada (the Crown) began when they exercised jurisdiction over the first nations and it was by Royal Proclamation that the first piece of legislation the British government passed over First Nations citizens assumed control of their lives. It gave recognition to the Indians tribes as First Nations living under Crown protection.

It was after the treaty of Paris in 1763, whereby France ceded all claims in present-day Canada to Britain, that King George III of Great Britain issued a Royal Proclamation specifying how the Indigenous in the crown colony were to be treated. It is the most significant pieces of legislation regarding the Crown's relationship with Aboriginal people. This Royal Proclamation recognized Indian owned lands and reserved to them all use as their hunting grounds. It also established the process by which the Crown could purchase their lands, and also laid out basic principles to guide the Crown when making treaties with the First Nations. The Proclamation made Indian lands transferred by treaty to be Crown property, and stated that indigenous title is a collective or communal rather than a private right so that individuals have no claim to lands where they lived and hunted long prior to European colonization.[76]

Indian Acts

In 1867, the British North America Act made land reserved for Indians a Crown responsibility. In 1876 the first of many Indian Acts passed, each successive one leeched more from the rights of the indigenous as was stated in the first. The sundry revised Indian Acts (22 times by 2002) solidified the position of Natives as wards of the state, and Indian agents were given discretionary power to control almost every aspect of the lives of the indigenous.[77] It then became necessary to have permission from an Indian agent if Native people wanted to sell crops they had grown and harvested, or wear traditional clothes off the reserves. The Indian Act was also used to deny Indians the right to vote until 1960, and they could not sit on juries.[78]

In 1885, General Middleton after defeating the Metis rebellion[79][80] introduced the Pass System in western Canada, under which Natives could not leave their reserves without first obtaining a pass from their farming instructors permitting them to do so.[81] While the Indian Act did not give him such powers, and no other legislation allowed the Department of Indian Affairs to institute such a system,[81] and it was known by crown lawyers to be illegal as early as 1892, the Pass System remained in place and was enforced until the early 1930s. As Natives were not permitted at that time to become lawyers, they could not fight it in the courts.[82] Thus was institutional racism externalized as official policy.

When Aboriginals began to press for recognition of their rights and to complain of corruption and abuses of power within the Indian department, the Act was amended to make it an offence for an Aboriginal person to retain a lawyer for the purpose of advancing any claims against the crown.[83]

Métis

Unlike the effect of those Indian treaties in the North-West, which established the reserves for the Indigenous, the protection of Métis lands was not secured by the scrip policy instituted in the 1870s,[84] whereby the crown exchanged a scrip[85] in exchange for a fixed (160–240 acres)[86] grant of land to those of mixed heritage.[87]

Although Section 3 of the 1883 Dominion Lands Act set out this limitation, this was the first mention in the orders-in-council confining the jurisdiction of scrip commissions to ceded Indian territory. However, a reference was first made in 1886 in a draft letter of instructions to Goulet from Burgess. In most cases, the scrip policy did not consider Métis ways of life, did not guarantee their land rights, and did not facilitate any economic or lifestyle transition.[88]

Most Métis were illiterate and did not know the value of the scrip, and in most cases sold them for instant gratification due to economic need to speculators who undervalued the paper. Needless to say, the process by which they applied for their land was made deliberately arduous.[89]

There was no legislation binding scrip land to the Métis who applied for them, Instead, Métis scrip lands could be sold to anyone, hence alienating any Aboriginal title that may have been vested in those lands. Despite the evident detriment to the Métis, speculation was rampant and done in collusion with the distribution of scrip. While this does not necessarily preclude a malicious intent by the federal government to consciously 'cheat' the Métis, it illustrates their apathy towards the welfare of the Métis, their long-term interests, and the recognition of their Aboriginal title. But the point of the policy was to settle land in the North-West with agriculturalists, not keep a land reserve for the Métis. Scrip, then, was a major undertaking in Canadian history, and its importance as both an Aboriginal policy and a land policy should not be overlooked as it was an institutional 'policy' that discriminated against ethnic indigenous to their continued detriment.[90]

Enfranchisement

Until 1951, the various Indian Acts defined a 'person' as "an individual other than an Indian", and all indigenous peoples were considered wards of the state. Legally, the Crown devised a system of enfranchisement whereby an indigenous person could become a "person" in Canadian law. Indigenous people could gain the right to vote and become Canadian citizens, "persons" under the law, by voluntarily assimilating into European/Canadian society.[91][92]

It was hoped that indigenous peoples would renounce their native heritage and culture and embrace the 'benefits' of civilized society. Indeed, from the 1920s to the 1940s some Natives did give up their status to receive the right to go to school, vote, or drink. However, voluntary enfranchisement proved a failure when few natives took advantage.[93]

In 1920, a law was passed to authorize enfranchisement without consent, and many Aboriginal peoples were involuntarily enfranchised. Natives automatically lost their Indian status under this policy and also if they became professionals such as doctors or ministers, or even if they obtained university degrees, and with it, their right to reside on the reserves.

The enfranchisement requirements particularly discriminated against Native women, specifying in Section 12 (1)(b) of the Indian Act that an Indian status woman marrying a non-Indian man would lose her status as an Indian, as would her children. In contrast non-Indian women marrying Indian men would gain Indian status.[94] Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, neatly expressed the sentiment of the day in 1920: "Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question and no Indian Department" This aspect of enfranchisement was addressed by passage of Bill C-31 in 1985,[95] where the discriminatory clause of the Indian Act was removed, and Canada officially gave up the goal of enfranchising Natives.

Residential schools

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Canadian federal government's Indian Affairs Department officially encouraged the growth of the Indian residential school system as an agent in a wider policy of assimilating Native Canadians into European-Canadian society. This policy was enforced with the support of various Christian churches, who ran many of the schools. Over the course of the system's existence, approximately 30% of native children, roughly some 150,000, were placed in residential schools nationally, with the last school closing in 1996. There has long been controversy about the conditions experienced by students in the residential schools. While day schools for First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children always far outnumbered residential schools, a new consensus emerged in the early 21st century that the latter schools did significant harm to Aboriginal children who attended them by removing them from their families, depriving them of their ancestral languages, undergoing forced sterilization for some students, and by exposing many of them to physical and sexual abuse by staff members, and other students, and dis-enfranchising them forcibly.[96]

With the goal of civilizing and Christianizing Aboriginal populations, a system of 'industrial schools' was developed in the 19th century that combined academic studies with "more practical matters" and schools for Natives began to appear in the 1840s. From 1879 on these schools were modelled after the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, whose motto was "Kill the Indian in him and save the man".[97] It was felt that the most effective weapon for "killing the Indian" in them, was to remove children from their Native supports and so Native children were taken away from their homes, their parent, their families, friends and communities.[98] The 1876 Indian Act gave the federal government responsibility for Native education and by 1910 residential schools dominated the Native education policy. The government provided funding to religious groups such as the Catholic, Anglican, United Church and Presbyterian churches to undertake Native education. By 1920, attendance by natives was made compulsory and there were 74 residential schools operating nationwide. Following the ideas of Sifton and others like him, the academic goals of these schools were "dumbed down". As Duncan Campbell Scott stated at the time, they did not want students that were "made too smart for the Indian villages":[99] "To this end the curriculum in residential schools has been simplified and the practical instruction given is such as may be immediately of use to the pupil when he returns to the reserve after leaving school."

The funding the government provided was generally insufficient and often the schools ran themselves as "self-sufficient businesses", where 'student workers' were removed from class to do the laundry, heat the building, or perform farm work. Dormitories were often poorly heated and overcrowded, and the food was less than adequately nutritious. A 1907 report, commissioned by Indian Affairs, found that in 15 prairie schools there was a death rate of 24%.[100] Indeed, a deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs at the time commented: "It is quite within the mark to say that fifty percent of the children who passed through these schools did not benefit from the education which they had received therein." While the death rate did decline in later years, death would remain a part of the residential school tradition. The author of that report to the BNA, Dr. P.H. Bryce, was later removed and in 1922 published a pamphlet[101] that came close to calling the governments indifference to the conditions of the Indians in the schools 'manslaughter'.[100]

Anthropologists Steckley and Cummins note that the endemic abuses – emotional, physical, and sexual – for which the system is now well known for "might readily qualify as the single-worst thing that Europeans did to Natives in Canada".[102] Punishments were often brutal and cruel, sometimes even life-threatening or life-ending. Pins were sometimes stuck in children's tongues for speaking their Native languages, sick children were made to eat their vomit, and semi-formal inspections of children's genitalia were carried out.[103] The term Sixties Scoop (or Canada Scoops) refers to the Canadian practice, beginning in the 1960s and continuing until the late 1980s, of taking ("scooping up") children of Aboriginal peoples in Canada from their families for placing in foster homes or adoption.

Most residential schools closed in the 1970s, with the last one closing in 1996. Criminal and civil suits against the government and the churches began in the late 1980s and shortly thereafter the last residential school closed. By 2002 the number of lawsuits had passed 10,000. In the 1990s, beginning with the United Church, the churches that ran the residential schools began to issue formal apologies. And in 1998 the Canadian government issued the Statement of Reconciliation,[104] and committed $350 million in support of a community-based healing strategy to address the healing needs of individuals, families and communities arising from the legacy of physical and sexual abuse at residential schools. The money was used to launch the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.[105]

Starting in the 1990s, the government started a number of initiatives to address the effects of the Indian residential school. In March 1998, the government made a Statement of Reconciliation and established the Aboriginal Healing Foundation. In the fall of 2003, the Alternative Dispute Resolution process was launched, which was a process outside of court providing compensation and psychological support for former students of residential schools who were physically or sexually abused or were in situations of wrongful confinement. On 11 June 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a formal apology on behalf of the sitting Cabinet and in front of an audience of Aboriginal delegates. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission ran from 2008 through to 2015 to document past wrongdoing in the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past.[106] The final report concluded that the school system amounted to cultural genocide.[107]

Contemporary situation

The overt institutional racism of the past has clearly had a profoundly devastating and lasting effect on visible minorities and Aboriginal communities throughout Canada.[108] European cultural norms have imposed themselves on Native populations in Canada, and Aboriginal communities continue to struggle with foreign systems of governance, justice, education, and livelihood. Visible Minorities struggle with education, employment and negative contact with the legal system across Canada.[109]

Perhaps most palpable is the dysfunction and familial devastation caused by residential schools. Hutchins states;[102] "Many of those who attended residential schools have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, suffering from such symptoms as panic attacks, insomnia, and uncontrollable or unexplainable anger.[110] Many also suffer from alcohol or drug abuse, sexual inadequacy or addiction, the inability to form intimate relationships, and eating disorders. Three generations of Native parents lost out on learning important parenting skills usually passed on from parent to child in caring and nurturing home environments,[111] and the abuse suffered by students of residential schools has begun a distressing cycle of abuse within many Native communities." The lasting legacy of residential schools is but only one facet of the problem.[112]

The Hutchins report continues: "Aboriginal children continue to struggle with mainstream education in Canada. For some Indian students, English remains a second language, and many lack parents with sufficient education themselves to support them. Moreover, schooling in Canada is based on an English written tradition, which is different from the oral traditions of the Native communities.[113] For others, it is simply that they are ostracised for their 'otherness'; their manners, their attitudes, their speech, or a hundred other things which mark them out as different. "Aboriginal populations continue to suffer from poor health. They have seven years less life expectancy than the overall Canadian population and almost twice as many infant deaths. While Canada as a nation routinely ranks in the top three on the United Nations Human Development Index,[114] its on-reserve Aboriginal population, if scored as a nation, would rank a distant and shocking sixty-third."

As Perry Bellegarde National Chief, Assembly of First Nations, points out, racism in Canada today is for the most part, a covert operation.[115] Its central and most distinguishing tenet is the vigour with which it is consistently denied.[116] There are many who argue that Canada's endeavors in the field of human rights and its stance against racism have only resulted in a "more politically correct population who have learnt to better conceal their prejudices".[117] In effect, the argument is that racism in Canada is not being eliminated, but rather is becoming more covert, more rational, and perhaps more deeply imbedded in our institutions.

That racism is alive is evidenced by the recent referendum in British Columbia by which the provincial government is asking the white majority to decide on a mandate for negotiating treaties with the Indian minority.[118] The results of the referendum will be binding,[119] the government having legislatively committed itself to act on these principles if more than 50% of those voting reply in the same way. Moreover, although it has been revised many times, "the Indian Act remains legislation which singles out a segment of society based on race". Under it, the civil rights of First Nations peoples are "dealt with in a different manner than the civil rights of the rest of Canadian citizens".[102]

The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in Manitoba,[120] the Donald Marshall Inquiry in Nova Scotia,[121] the Cawsey Report in Alberta[122] and the Royal Commission of Aboriginal People all agree,[123] as far as Aboriginal people are concerned, racism in Canadian society continues institutionally, systematically, and individually.

In 2020, after the death of Joyce Echaquan, the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, had recognized a case of systemic racism.

In 2022, Pope Francis visited Canada for a week-long tour called a “pilgrimage of penance.”[124] Vatican officials called the trip a “penitential pilgrimage”. The Pope was welcomed in Edmonton where he apologized for Indigenous abuse which took place in the 20th century at Catholic run residential schools which have since closed.[125] During his stay he met with Indigenous groups to address the scandal of the residential schools.[126] “I am sorry,” The Pope said, and asked forgiveness for the church and church members in “projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation” and the systematic abuse and erasure of indigenous culture in the country’s residential schools.[127]

Anti-Chinese immigration laws

The Canadian government passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 levying a $50 head tax upon all Chinese people immigrating to Canada. When the 1885 act failed to deter Chinese immigration, the Canadian government then passed the Chinese Immigration Act, 1900, increasing the head tax to $100, and, upon that act failing, passed the Chinese Immigration Act, 1904 increasing the head tax (landing fee) to $500, equivalent to $8000 in 2003[128] – when compared to the head tax – Right of Landing Fee and Right of Permanent Residence Fee – of $975 per person, paid by new immigrants in 1995–2005 decade, which then was reduced to $490 in 2006.[129]

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, better known as the "Chinese Exclusion Act", replaced prohibitive fees with a ban on ethnic Chinese immigrating to Canada – excepting merchants, diplomats, students, and "special circumstance" cases. The Chinese who entered Canada before 1923 had to register with the local authorities, and could leave Canada only for two years or less. Since the Exclusion Act went into effect on 1 July 1923, Chinese-Canadians referred to Canada Day (Dominion Day) as "Humiliation Day",[130] refusing to celebrate it until the Act's repeal in 1947.[131]

Black Canadians

There are records of slavery in some areas of British North America, which later became Canada, dating from the 17th century. The majority of these slaves were Aboriginal,[132] and United Empire Loyalists brought slaves with them after leaving the United States. Marie-Joseph Angélique was one of New France's best-known slaves. While pregnant, she set her mistress' house on fire for revenge or to divert the attention away from her escape. She ran away with the father of her child, who was also a black slave and belonged to another owner. The fire that she started ended up burning part of Montreal and a large portion of the Hôtel-Dieu. Later on, she was caught and sentenced to death.

China

Institutional racism exists in many domains in the People's Republic of China, though certain scholars have noted the Chinese government's portrayal of racism as a Western problem, while intentionally ignoring or downplaying the existence of widespread systemic racism in China.[133][134]

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination reported in 2018 that Chinese law does not define racial discrimination.[135]

Uyghurs

Under the leadership of China's Paramount Leader and Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping, the Uyghurs – a mostly Muslim ethnic minority group living in the Chinese Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region – have faced widespread persecution from authorities and mass detentions.[136] Since 2017, it has been reported that least 1 million Uyghur Muslims have been detained in "re-education camps" commonly described as concentration camps,[137][138] where they have been subject to torture, forced labor, religious discrimination, political indoctrination and other human rights abuses.[139][140][141][142][143] Testimonials from escaped inmates have indicated inmates are subject to forced sterilization.[144][145]

Birth rates in two Xinjiang regions have dropped by more than 60% between 2015 and 2018, a result of measures by the Chinese government to lower the Uyghur population artificially.[146][147] The situation has been described as an ongoing genocide by numerous sources,[148][149][150][151] and others have argued that it is likely the "largest mass detention of a religious minority group" since the Holocaust according to the New Statesman.[152] A study from 2013 found local government officials in China "were 33 percent less likely to provide assistance to citizens with ethnic Muslim names than to ethnically-unmarked peers."[153]

Tibetans

Since the People's Republic of China gained control of Tibet in 1951, there has been institutional racism in the form of an elaborate propaganda system designed by the Chinese Communist Party to portray Tibetans as being liberated from serfdom through China and Han Chinese culture. A state-organized historical opera performed in 2016 in China portrayed Tibet as being unsophisticated prior to Princess Wencheng's marriage to Songtsen Gampo, a Tibetan emperor, in the year 641. This propaganda is described by Tibetan activist Tsering Woeser as being a "...vast project that rewrites history and 'wipes out' the memory and culture of an entire people."[154]

A 1991 journal article identified how forced abortion, sterilization, and infanticide in Tibet were all part of a severe CCP birth control program in the region, designed specifically to target Tibetans.[155]

A paper submitted to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination by the Tibetan government in exile stipulates about how Tibetans face an education system which is inequitable compared with the education for Han Chinese. According to the paper, only about nine percent of Chinese adults are illiterate, compared with about sixty percent of Tibetans in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. Furthermore, Tibetan children are prevented from learning about their own history and culture, and forbidden to learn their own language. Schools in the region often have racial segregation based on ethnic characteristics, with Tibetan students receiving worse education in poorly-maintained classrooms.[156]

During the 2008 Tibet protests, a local eyewitness claimed Chinese military police "were grabbing monks, kicking and beating them" after riots around the closure of the Sera monastery near Lhasa.[157]

Anti-African sentiment

Racism against African people or people perceived to be of African descent has long been documented in China.

Published in 1963, African student Emmanuel Hevi's An African Student in China details "the arrests of Chinese girls for their friendships with Africans, and particularly, Chinese feelings of racial superiority over black Africans."[158] One notable instance was the Nanjing anti-African protests of 1988, in which African university students were the subject of racist beatings and other attacks. In some cases, Chinese university students shouted racist slogans such as "'Down with the black devils!' and 'Blood for blood!'"[159] Despite these obvious instances of racism against Africans, the Chinese state media portrayed the attacks as being instigated by the African students.

In modern China, racism remains an issue in certain universities, such as the state-funded Zhejiang Normal University. A black graduate student described how "African students would hear Professors and classmates make xenophobic comments, such as 'Africans are draining our scholarship funds'" and how African students, despite having higher grades, were receiving lower level scholarship funds through the ZJNU's three-tiered scholarship system than their classmates.[160]

One study noted how Africans were being portrayed as "waste" and "triple illegals" through racial profiling by police in Guangzhou.[161] In 2007, African nationals were targeted in Beijing's Sanlitun district by police during an anti-drug raid. They were the victims of police brutality and targeted on the basis of their skin color, something which the police later denied.[162]

State media reports from 2008 referred to Africans in a racist manner, as Cheng explains: "...[the] language often remained demeaning regarding Africans as much less civilized people. Chinese words such as 部落 (buluo, "tribes") or 聚居地/ 群居/群落 (jujudi/qunju/qunluo, habitats), instead of 社区 (shequ, community) were often used to refer to Africans."[163]

Yinghong Cheng asserts in a 2011 journal article that "Cyber racism against Africans is certainly not the only racial thinking but it is perhaps the most explicit and blatant one."[163] He details the ubiquity of "manifestations of racial stereotypes, hierarchy perception and insensitivity", in addition to how "systematic discourse of race has developed in much more articulate, sophisticated and explicit ways in education and pop culture to accommodate contemporary Chinese nationalism."[163] The adoption of a more state capitalist form of government in the PRC has led to the widespread internet popularity of commercialized Chinese singers and songwriters, some of whose material is racial in subject matter. As Cheng notes: "'The Yellow Race' (Huangzhongren 黄种人) and 'Yellow' (Huang 黄), [were] created in 2006 and 2007 respectively and dedicated to China's hosting of the Olympics. The racist language in these songs, such as 'the Yellow Race is now marching on the world,' combined with nationalist claims such as 'After 5,000 years, finally it is the time for us to show up on the stage,' coloured Xie's popularity among his young Chinese fans."[163]

In 2018, CCTV New Year's Gala, a state media television programme which has in the past been viewed by up to 800 million people included a racist neocolonial skit featuring a Chinese actress who wore blackface makeup. The skit "praises Chinese-African cooperation, showing how much Africans benefit from Chinese investment and how grateful they are to Beijing."[164] Later the same year, the Daily Monitor reported that citizens of Uganda and Nigeria were discriminated against in Guangzhou by the Chinese government, through incidents such as taxis being halted and passports from African countries being confiscated, as well as hotels and restaurants being ordered to erect notices banning service to Africans.[165] In addition, some African-owned stores were forcibly shut down.[165]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple instances of systemic racism against African people were documented, including misinformation and racist stereotyping which portrayed Africans as carriers of the virus. According to The Guardian, Africans were "refused entry by hospitals, hotels, supermarkets, shops and food outlets. At one hospital, even a pregnant woman was denied access. In a McDonald's restaurant, a notice was put up saying 'black people cannot come in.'"[166] The local government in Guangzhou implemented mass surveillance, compulsory testing, and enforced a 14-day quarantine for all African nationals, regardless of whether they had traveled outside of China in the past two weeks.[166]

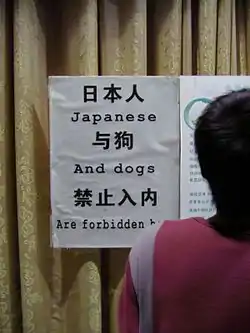

Anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment exists as a modern issue in China, largely due to historical grievances. There have been reports of restaurants and public institutions refusing service or entry to Japanese people, which stems especially due to the Second Sino-Japanese War which had included Japanese war crimes such as the Nanjing massacre and Unit 731.[167][168]

In recent years, there has been joint communiqués between the leaders of these two countries to try and mend as well as improve relations with each other.[169][170]

Malaysia

Malaysians of Chinese and Indian descent – who make up a significant portion of ethnic minorities in Malaysia, with them making up around 23.2% and 7.0% of the population respectively[171] – were granted citizenship by the Malaysian Constitution but this implied a social contract that left them at a disadvantage and discriminated in other ways, as Article 153 of the Constitution of Malaysia refers to the special "position" and "privileges" of the Muslim Malay people as supposed initial dwellers of the land.

Malay supremacy

However, due to the concept of Ketuanan Melayu (lit. Malay supremacy), a citizen that is not considered to be of Bumiputera status face many roadblocks and discrimination in matters such as economic freedom, education, healthcare and housing.[172] Opposition groups, government critics and human rights observers has labeled the Malaysian situation as being highly similar to apartheid policies due to their status as de facto second-class citizens.[173] Such policies has also led to a significant brain drain from the country.[174]

In 1970, the Malaysian New Economic Policy a program of affirmative action aimed at increasing the share of the economy held by the Malay population, introduced quotas for Malays in areas such as public education, access to housing, vehicle imports, government contracts and share ownership. Initially meant as a measure to curb the poor economic participation of the Malays, aimed to reduce the number of hardcore poor Malays, it is now perceived by most conservative Malays as a form of entitlement or 'birthright'.[175] In post-modern Malaysia, this entitlement in political, legislative, monarchy, religious, education, social, and economic areas has led to lower productivity and lower competitiveness among the Malays.[176]

As for the elite Malays, this 'privilege' has been abused to the point where the poor Malays remain poor, while the rich Malays becomes richer; which is the result of Malay cronyism, non-competitive and non-transparent government project tender processes favouring Bumiputera candidates – causing deeper intra-ethnic inequality.[177] However, the actual indigenous people or better known as Orang Asli remain marginalised and have their rights ignored by the Malaysian government.[178] Since Article 160 defines a Malay as "professing the religion of Islam", those eligible to benefit from laws assisting bumiputra are, in theory, subject to religious law enforced by the parallel Syariah Court system.

While 179 countries around the world have ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), Malaysia is also not one of them. The Pakatan Harapan (PH) government that replaced Barisan Nasional (BN) from 2018 to 2020 had indicated a readiness to ratify ICERD, but has yet to do so due to the convention's conflict with the Malaysian constitution and the race and religious norms in Malaysia established since its independence.[179] Furthermore, a mass rally was held in 2018 by Malay supremacists at the country's capital to prevent such ratification, threatening racial conflicts if they do so.[180] The PH government would eventually lose power amid the 2020–2022 Malaysian political crisis to BN.[181]

Nigeria

Indigeneity

Nigeria contains over 250 ethnic groups, but the country is politically dominated by three major ethnic groups – the Hausa-Fulani of the north, the Igbo of the southeast, and the Yoruba of the southwest. National politics in Nigeria have largely revolved around competition between the three dominant ethnic groups, with the minority ethnic groups having less political representation.[182]

The Nigerian constitution promises equality among all ethnic groups, but in actuality, the concept of "indigeneity" is widespread across local and state governments (and to a lesser extent, the federal government), which has been criticized by Human Rights Watch as a form of discrimination and a violation of international human rights law.[183] Citizens are recognized as "indigenes" of a particular locality if they belong to an ethnic group that is considered to be indigenous to that locality.[184] Citizens from other ethnic groups, regardless of how long they or their families have been living in a locality, are legally recognized as non-indigenes and they face discrimination from government laws that limit their socioeconomic mobility.[184]

Public universities in Nigeria favour indigenes during the admissions process, and non-indigenes are subject to discriminatory admissions policies that attempt to limit the number of non-indigene students.[184] Non-indigene students are required to pay higher tuition and they are denied academic scholarships.[184] Non-indigenes are often unable to participate in local politics and they are also excluded from government jobs.[184] In some cases, non-indigenes have faced mass purges from government jobs in order to create more jobs for indigenes.[183]

Human Rights Watch has claimed the indigeneity policies relegate "millions of Nigerians to the status of second-class citizens".[183] Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo compared indigeneity policies to apartheid.[185]

Niger Delta ethnic minorities

Nigeria is an oil-rich country where much of its oil resources can be found in the Niger Delta region, which is inhabited by ethnic minorities such as the Ogoni and Ijaw. The native inhabitants of the Niger Delta do not receive much of the wealth generated by Nigeria's vast oil industry, and it is paradoxically one of Nigeria's poorest regions.[186] Oil wealth has been used to develop other parts of Nigeria while the Niger Delta region itself remains underdeveloped.[187] The Niger Delta is constantly polluted and destroyed by the activities of both the Nigerian government and oil companies such as Shell Nigeria and Chevron Nigeria.[188] Struggle for oil wealth has fueled violence in the Niger Delta, causing the militarization of nearly the entire region by ethnic militia groups and Nigerian military and police forces.[189]

The Ijaw and Ogoni people have been subject to human rights violations in the form of environmental destruction and pollution.[190] A 1979 amendment to the Nigerian constitution gave the federal government the authority to seize and distribute Ogoni territory to oil companies without any compensation.[191] In 1990, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People was founded by Ogoni activist Ken Saro-Wiwa to seek self-determination for the Ogoni people, compensation for environmental destruction, and payment of royalties from oil production.[192] In 1995, he was arrested and executed, along with nine other Ogoni activists, by the regime of the Nigerian military dictator Sani Abacha, which was internationally condemned as a violation of human rights.

While the Nigerian government has become more democratic ever since the death of Sani Abacha, the ethnic groups in the Niger Delta still lack representation and remain excluded from the mainstream of Nigerian politics, economy and society. Government security forces in the Delta region regularly engage in torture, killings and confiscation of property as a result of the Conflict in the Niger Delta.[193] The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization condemned the Nigerian government for its discrimination against the Ogoni people and failure to clean environmental pollution from the Niger Delta region.[194]

Osu

The Igbo people traditionally maintain a system of discrimination from the Odinani religion that discriminates against a class of people known as Osu (Igbo: outcast).[195] Osu are regarded to be spiritually inferior beings, and they are distinguished from Nwadiala or diala (Igbo: real born). They are ostracized from wider society and Igbo are discouraged from marrying them. They were historically either sold into slavery or were delivered to be enslaved to certain deities who were believed to ask for human sacrifice during festivals in order to clean the land from abomination, thus leading to the purchase of a slave by the people.

The status of Osu is permanent and inherited at birth.[196] Despite influence from colonialism and Christianity, discrimination against Osu still persists in the modern day.[197] In modern times, Osu are often barred from marriage, traditional leadership positions, and running from political office.[196]

According to some human rights groups who are calling for its abolishment, some of the punishments meted out against the Osu include: parents administering poison to their children, disinheritance, ostracism, denial of membership in social clubs, violent disruption of marriage ceremonies, denial of chieftaincy titles, deprivation of property and expulsion of wives.[198]

South Africa

In South Africa, during apartheid, institutional racism has been a powerful means of excluding from resources and power any person not categorized or marked as a white. Those marked as black were further discriminated against differentially, with Africans facing more extreme forms of exclusion and exploitation than those marked as Coloured or Indian. One such example of institutional racism in South Africa is Natives Land Act, 1913, which reserved 90% of land for white use and the Native Urban Areas Act of 1923 controlled access to urban areas, which suited commercial farmers who were keen to hold labour on their land. Africans, who formed the majority of the population, were relegated to (often barren) rural reserves, which later became homelands.[199]

More modern forms of institutional racism in South Africa are centered around interracial relationships and official government policy. Opposition to interracial intimate relationships may be indicative of underlying racism, and that conversely acceptance and support of these relationships may be indicative of a stance against racism.[200] Even though the prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act was repealed in 1985, the term "mixed" continued to exists, thus carrying forth the inherent stigmatization of "mixed" relationships and race. Consequently, discourse is a framework that realizes that language can produce institutional structures and relations. However, language constitutes who we are, how we interact with others and how we understand ourselves. Therefore, discourse is said to be inextricably linked to power and more than just a medium used to transmit information.[200]

Furthermore, post-apartheid racism is still rife in South Africa, both black-on-white and white-on-black, with white-on-black racism being more advertised in the news. In 2015, black staff at a restaurant near Stellenbosch allegedly were verbally attacked and degraded by a group of white students. In response, a black student declared that everyone who did not speak Afrikaans in the area was an alien in the area. "They were whistling at them as they were whistling at dogs," he claimed. He further claimed that the white students even leapt over the counter and patted them as if they were dogs. Three white men and four other young white men allegedly followed him outside after he left the restaurant and assaulted him.[201] The University of Stellenbosch did not continue with disciplinary action which shows the racism in academic institutions.

The South African government has done things to combat racial economic disparity in South Africa for example, BEE (Black Economic Empowerment) is a South African government programme aimed at facilitating black people's fuller participation in the economy, particularly to address imbalances established by apartheid. It offers incentives to businesses that contribute to black economic empowerment through a variety of measurable criteria, such as partial or majority black ownership, hiring black employees, and contracting with black-owned suppliers, as well as preferential treatment in government procurement processes. BEE's preferential procurement feature has been hailed as a model for a long-term procurement strategy in which government procurement is used to accomplish social policy goals.

United Kingdom

In the Metropolitan Police Service

In the United Kingdom, the inquiry about the murder of the Black Briton Stephen Lawrence concluded that the investigating police force was institutionally racist. Sir William Macpherson used the term as a description of "the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin", which "can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes, and behaviour, which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness, and racist stereotyping, which disadvantages minority ethnic people".[202] Sir William's definition is almost identical to Stokely Carmichael's original definition some forty years earlier. Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton were Black Power activists and first used the term 'institutional racism' in 1967 to describe the consequences of a societal structure that was stratified into a racial hierarchy that resulted in layers of discrimination and inequality for minority ethnic people in housing, income, employment, education and health (Garner 2004:22).[203]

The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report, and the public's response to it, were among the major factors that forced the Metropolitan Police to address its treatment of ethnic minorities. More recently, the former Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Ian Blair said that the British news media are institutionally racist,[204] a comment that offended journalists, provoking angry responses from the media, despite the National Black Police Association welcoming Blair's assessment.[205]

The report also found that the Metropolitan Police was institutionally racist. A total of 70 recommendations for reform were made. These proposals included abolishing the double jeopardy rule and criminalising racist statements made in private. Macpherson also called for reform in the British Civil Service, local governments, the National Health Service, schools, and the judicial system, to address issues of institutional racism.[206]

In June 2015, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, said there was some justification in claims that the Metropolitan Police Service is institutionally racist.[207]

In criminal convictions

In the English and Welsh prison system, government data which was compiled in 2020 showed that youths of color are dis-proportionally subject to punishment the UN regards as violating the Mandela Rules on the treatment of prisoners. The COVID-19 pandemic had caused some minors being held in pre-trial detention to be placed in solitary confinement indefinitely.[208][209] Minorities under 18 comprised 50% of the youth inmates held and 27% of the overall prison population. Ethnic minorities made up 14% of the overall population.

In healthcare

Institutional racism exists in various aspects of healthcare, from maternity to psychiatric. Black women are four times more likely to die in pregnancy, labour and up to a year postpartum than whites.[210]

Asian women are twice as likely as whites to die in pregnancy. Black women are twice as likely to have a stillborn baby than whites.[211]

According to the Institute for the Study of Academic Racism, scholars have drawn on a 1979 work by social psychologist Michael Billig – "Psychology, Racism, and Fascism" – that identified links between the Institute of Psychiatry and racist/eugenic theories, notably in regard to race and intelligence, as for example promoted by IOP psychologist Hans Eysenck and in a highly publicised talk in August 1970 at the IOP by American psychologist Arthur Jensen. Billig concluded that "racialist presuppositions" intruded into research at the Institute both unintentionally and intentionally.[212] In 2007, the BBC reported that a "race row" had broken out in the wake of an official inquiry that identified institutional racism in British psychiatry, with psychiatrists, including from the IOP/Maudsley, arguing against the claim,[213] while the heads of the Mental Health Act Commission accused them of misunderstanding the concept of institutional racism and dismissing the legitimate concerns of the black community in Britain.[214] Campaigns by voluntary groups seek to address the higher rates of sectioning, overmedication, misdiagnosis and forcible restraint on members of minority groups.[215] According to 2014 statistics, Black adults had the lowest treatment rate of any ethnic group, at 5.2%. The treatment rate for whites is 17.3%.[216] Figures from March 2019 show that Black people were more than four times as likely as white people to be detained under the Mental Health Act in the previous year.[217]

Black men were 4.2 times more likely, and Black women were 4.3 times more likely, to die from COVID-19 than whites during the initial wave of the pandemic.[218]

In education

In a 2009 report by the Department for Innovations and Business Skills, it was found that Black students were the most likely to receive under-predicted grades by their teachers. It was found that 8.1% of Black students received higher actual grades compared to 4.6% of white students, 6.5% of Asian students and 6.1% of mixed-race students.[219]

Critics contend that part of the institutional racism in education in the UK is in the curriculum. Arguments for and against decolonizing the curriculum are outlined on the BBC's Moral Maze podcast.[220]

In employment

The equality and human rights commission reported that black workers with degrees earned 27.1% less income on average than whites.[221] This gives some light for the reasons behind the stark inequalities that black people and to a lesser extent, other ethnic minorities face in the UK. For example, 56% of families with a black household head were living in poverty compared to 13% of families led by a white person.[222]

Standards of employment in the UK, as well as in the United States and other Western European countries, often disregard how certain standards, such as eye contact, have different meanings around the world.[223] Asian, Latin American and African cultures can consider eye contact as disrespect or as challenging authority, often resulting in them maintaining an on-and-off eye contact to show respect in interviews and employment processes. Opposingly, most people in countries in North America and Western Europe see eye contact as expressing enthusiasm and trust.

United States

In housing and lending