Jacques Anquetil

Jacques Anquetil (pronounced [ʒak ɑ̃k.til]; 8 January 1934 – 18 November 1987) was a French road racing cyclist and the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, in 1957 and from 1961 to 1964.[1]

Anquetil at the 1966 Giro d'Italia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Jacques Anquetil | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Monsieur Chrono Maître Jacques | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 8 January 1934 Mont-Saint-Aignan, France | |||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 November 1987 (aged 53) Rouen, France | |||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.76 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 70 kg (154 lb; 11 st 0 lb) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Road and track | |||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rider type | All-rounder | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amateur team | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1950–1952 | AC Sottevillais | |||||||||||||||||||

| Professional teams | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1953–1955 | La Perle | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1956–1958 | Helyett–Potin–Hutchinson | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1959–1960 | Alcyon–Dunlop | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1961–1964 | Saint-Raphaël–R. Geminiani–Dunlop | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1965–1966 | Ford France–Gitane | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1967–1969 | Bic–Hutchinson | |||||||||||||||||||

| Major wins | ||||||||||||||||||||

Grand Tours

Stage races

One-day races and Classics

Other

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||

He stated before the 1961 Tour that he would gain the yellow jersey on day one and wear it all through the tour, a tall order with two previous winners in the field—Charly Gaul and Federico Bahamontes—but he did it.[n 1] His victories in stage races such as the Tour were built on an exceptional ability to ride alone against the clock in individual time trial stages, which lent him the name "Monsieur Chrono".

He won eight Grand Tours in his career, which was a record when he retired and has only since been surpassed by Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault.

Early life

Anquetil was the son of a builder in Mont-Saint-Aignan, in the hills above Rouen in Normandy, north-west France. He lived there with his parents, Ernest and Marie, and his brother Philippe and then at Boisguillaume in a two-storey house, "one of those houses with exposed beams that tourists think are pretty but those who live there find uncomfortable."[2]

In 1941, his father refused contracts to work on military installations for the German occupiers and his work dried up. Other members of the family worked in strawberry farming and Anquetil's father followed them, moving to the hamlet of Bourguet, near Quincampoix. Anquetil had his first bicycle – an Alcyon – at the age of four and twice a day rode the kilometre and a half to the village and back. There he was taught by a teacher wearing clogs in a classroom heated by a smoking stove.[2]

Anquetil learned metal-turning at the technical college at Sotteville-lès-Rouen, a suburb of the city, where he played billiards with a friend named Maurice Dieulois. His friend joined the AC Sottevillais club with the encouragement of his father and began racing. Anquetil said:

...[I] was impressed by the way girls were attracted to Dieulois because he had become a coureur cycliste ... so I gave up my first choice – running – and joined the club as well."[2]

He was 17 and he took out his first racing licence on 2 December 1950. He stayed a member the rest of his life[3] and his grave in the churchyard at Quincampoix has a permanent tribute from his clubmates.

Anquetil passed his qualifications in light engineering and went to work for 50 old francs a day at a factory in Sotteville. He left after 26 days following a disagreement with his boss over time off for training. The AC Sottevillais, founded in 1898, was run by a cycle-dealer, André Boucher, who had a shop in the Place du Trianon in Sotteville.[3] The club had not just Anquetil but Claude LeBer, who became professional pursuit champion in 1955, Jean Jourden, world amateur champion in 1961, and Francis Bazire, who came second in the world amateur championship in 1963.

Boucher trained his group first from a bicycle and then by Derny. Anquetil made fast progress and won 16 times as an amateur. His first victory was the Prix Maurice Latour at Rouen on 3 May 1951. He also took the Prix de France in 1952 and the Tour de la Manche and the national road championship the same year.

The Grand Prix des Nations

Anquetil rode in the French team in the 100 km time trial at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki and won a bronze medal.[1] Impressed by his protégé's progress, André Boucher sent an envelope of Anquetil's press cuttings to the local representative of the Perle bicycle company and asked him to send them to the firm's cycling team manager, the former Tour de France rider, Francis Pélissier.[4]

Pélissier called Anquetil, who was surprised and flattered to hear from him, and offered him 30,000 old francs a month to ride for La Perle as an independent, or semi-professional. Anquetil accepted and immediately ordered a new car, a Renault Fregate, which he crashed twice in the first 12 months.[5]

Pélissier wanted Anquetil for the 1953 Grand Prix des Nations, a race started by the newspaper Paris-Soir which since 1932 had risen to the status of an unofficial world time-trial championship. It was held on a 142 km loop of rolling roads through Versailles, Rambouillet, Maulette, St-Rémy-les-Chevreuse and then back to Versailles before, originally, finishing on the Buffalo track in Paris.

Anquetil was aware that one of his rivals was an Englishman named Ken Joy, who had broken records in Britain but was unknown in France. He would ride with another Englishman, Bob Maitland.[5] The historian Richard Yates says:

Many of the 'against-the-clock' fraternity in the United Kingdom sincerely believed that the British time triallists were as good as, if not better than, their Continental counterparts and here was the chance to prove it. When the final result was known the British fans were disappointed and saw the race as a total failure for Britain as both Englishman had finished nearly 20 minutes down. To rub salt in the wounds, the event had been won by an unknown, curly-haired teenager from Normandy.[5]

Anquetil caught Joy — the moment he realised he was going to win the race[2] — even though Joy had started 16 minutes earlier. At 19, Anquetil had become unofficial time-trial champion of the world.

The win pleased Pélissier but did not convince him. Next year he drove his team car not behind Anquetil but his Swiss star, Hugo Koblet. Anquetil was not amused. When he beat Koblet, he sent his winner's bouquet to Pélissier's wife "in deepest sympathy".[2]

Anquetil rode the Grand Prix des Nations nine times without being beaten.

Hour record

On 22 September 1954, Anquetil started two years' compulsory service in the army, joining the Richepanse de Rouen barracks as a gunner of the 406th artillery regiment. The army accorded him few great favours but there was an exception:

In June 1956, my chiefs finally gave me an order more to my liking, the strangest, the most unusual that a gunner has ever been asked to carry out; it was nothing less than to beat the world hour record. I knew what that meant: to storm a veritable fortress. For 14 years, since 7 November 1942, the date on which Fausto Coppi planted the Italian flag on it, it had discouraged all assailants. One figure sums up the difficulty of the enterprise: 45.848 km.[2]

Should he break the record, he and the army agreed, he would give half the rewards to the army and the rest to the mother of a soldier, André Dufour, who had been killed while fighting at Palestro, in Algeria.[6] The chances of breaking it were far from guaranteed, not only because Coppi's record had already defied Gerrit Schulte and Louison Bobet but also Anquetil himself, on 23 November 1955, when he had started too fast, faded and finished 696 m short of Coppi. His second attempt also flopped. He again started too fast. After 54:36 his helpers called him to a stop after 41.326 km. His legs failed him when he got off his bike and he had to be carried to a chair in a corner of the Velodromo Vigorelli, the velodrome in Milan, Italy. The Italian crowd chanted: "Coppi! Coppi! Coppi!"[2][6]

I was like a child's lead soldier that has lost its horse."[2]

Next day he received a telegram: "Congratulations on a good performance. Sure of your success. Take your time. Captain Gueguen will arrive tomorrow with instructions. Signed: Commander Dieudonné".[6]

At 7:30pm on 29 June 1956, riding a lighter bike made in three days to the same design as Coppi's, and using a 7m40 gear (52x15), Anquetil tried again and finally broke his hero's record, riding 46.159 km. Coppi was the first professional to give Anquetil his autograph.[7] When the two next met, Anquetil was also a professional. He went to Italy to meet Coppi and, for reasons never explained, dressed as a simple country boy rather than in the smart clothes that he normally wore.

The grandstands fell quiet. They were preparing to take Coppi to the cemetery. I liked that silence. On the 84th lap, Boucher gave me my release. "Allez, môme, tout!" ["Go, kid, give it everything!"] Until then I had been well within myself [J'ai fumé ma pipe]... On a big school blackboard, Captain Gueguen wrote 46.159km. I could lift my arms, sit up and breathe a bit of fresh air. Ah, the public! Those who were whistling me four laps earlier kissed my bike, my jersey, reaching out to touch me in the way they do during processions of holy relics.[2]

In 1967, 11 years later, Anquetil again broke the hour record, with 47.493 km, but the record was disallowed because he refused to take the newly introduced post-race doping test.[8] He objected to what he saw as the indignity of having to urinate in a tent in a crowded velodrome and said he would take the test at his hotel. The international judge ruled against the idea and a scuffle ensued that involved Anquetil's manager, Raphaël Géminiani. Cycling reported:[9]

Wonderful Jacques Anquetil has broken the world hour record as he said he would... and then ran into official trouble when he refused to take a trackside dope test demanded by the Italian authorities. An Italian Dr Giuliano Marena asked for the urine sample, but Anquetil refused and asked him to come to his hotel. Dr Marena refused and, after waiting a couple of hours at the track, left town to go home to Florence. Anquetil said at his hotel: 'I didn't and don't intend to escape the test, but it must take place under circumstances far different from those at the velodrome. I'm still here and ready to undergo the test.' While Italian officials talked of taking the matter to the UCI, Dr Tanguy of the FFC [French cycling federation] took a sample from Anquetil on his return to Rouen, pointing out afterwards that it would be valid up to 48 hours after the record attempt. But Raphaël Géminiani, his manager, had all but lost his temper with the Italian medical man and had tried to throw him out of the cabin, though Jacques had remonstrated mildly. Later he said that he understood the tests would be valid for up to 48 hours and said he was trying to locate another doctor for the test.[9]

Tour de France

In 1957 Anquetil rode – and won – his first Tour de France. His inclusion in the national team – the Tour was still ridden by national rather than commercial teams – was what the French broadcaster Jean-Paul Ollivier called "a forceps operation".[10]

Louison Bobet and Raphaël Géminiani wished to rule the Tour de France and had no desire to have Anquetil. But Louison, worn out from his battle of nerves that he suffered in the Tour of Italy, where he used all his energy in defending the maglia rosa [leader's jersey] against the Italian surge [déferlante], declared, on the banks of the Adriatic; "I am not prepared, mentally, to take part in the Tour de France. I am 32 in a world of youth."[10]

Anquetil recognised the allusion and accepted the invitation to ride. He finished nearly 15 minutes ahead of the rest, winning four stages and the team stage.

In 1959, Anquetil was whistled as he finished the Tour on the Parc des Princes because spectators calculated that he and others had contrived to let Federico Bahamontes win rather than the Frenchman Henry Anglade. The French team was unbalanced by internal rivalries. Anglade, whose bossy nature earned him the nickname Napoleon, was unusual in that he was represented by the agent Roger Piel while the others had Daniel Dousset. The two men controlled French racing.[11] Dousset worked out that his riders had to beat Bahamontes or make sure that Anglade didn't win. Since they couldn't beat Anglade, they let Bahamontes win because Bahamontes, a poor rider on the flat and on small circuits, would be no threat to the post-Tour criterium fees that made up the bulk of riders' — and agents' — earnings.

Anquetil was jeered and showed his coldness to public reaction by buying a boat that he named "The Whistles of 59" and by pointing out that he was a professional and that his first interest was money. It was an attitude that other riders understood but made him hard for fans to love .

In 1960 Anquetil stayed away from the Tour, returning in 1961 and winning it thereafter until 1964. He won in 1962 at a speed not bettered until 1981. He was the first to win four successive times, breaking the record of three set by Philippe Thys and Louison Bobet. He was first to win five times in total, since emulated by Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain.

In 1963 Tour, at the top of a mountain, Anquetil faked a mechanical problem so that his team director could give him a bicycle more suitable for the descent. The plan worked and Anquetil overtook Bahamontes and won the stage, taking the lead.

His last Tour victory (in 1964) was his most famous, featuring an elbow-to-elbow duel with public favourite Raymond Poulidor on the road up the Puy de Dôme mountain on 12 July. Suffering indigestion after excesses on a rest day, Anquetil was said to have received a swallow of champagne from his team manager — a story Anquetil's wife says is untrue.

The Tour organiser, Jacques Goddet, was behind the pair as they turned off the main road and climbed through what the police estimated as half a million spectators. He recalled:

The two, at the extreme of their rivalry, climbing the road wrapped like a ribbon round the majestic volcano, terribly steep, in parallel action... I've always been convinced that in these moments that supreme player of poker, the Norman [Anquetil], used his craftiness and his fearless bluffing to win his fifth Tour. Because, to me, it was clear that Anquetil was at the very limit of his strength and that had Poulidor attacked him repeatedly and suddenly then he would have cracked... Although his advisers claim that his error in maintaining steady pressure rather than attacking was the result of using slightly too big a gear, which stopped his jumping away, I still think that it was in his head that Pou-Pou should have changed gears.[12]

Anquetil rode on the inside by the mountain wall while Poulidor took the outer edge by the precipice. They could sometimes feel the other's gasps on their bare arms. At the end, Anquetil cracked, after a battle of wills and legs so intense that at times they banged elbows. Of Anquetil, Pierre Chany wrote:

"His face, until then purple, lost all its colour; the sweat ran down in drops through the creases of his cheeks."[6]

Anquetil was only semi-conscious, he said.[6] Anquetil's manager, Raphaël Géminiani, said:

Anquetil's head was a computer. It started working: in 500 metres, Poulidor wouldn't get his 56 seconds. I'll never forget what happened when Jacques crossed the line. Close to fainting, he collapsed on the front of my car. With barely any breath left, exhausted, but 200 per cent lucid, he asked me: 'How much?' I told him 14 seconds. 'That's one more than I need. I've got 13 in hand'.

In my opinion Poulidor was demoralised by Anquetil's resistance, his mental strength. There were three times when he could have dropped Anquetil. First, at the bottom of the climb. Then when Julio Jimenez attacked [and left the two Frenchmen, accompanied by the rival climber Federico Bahamontes]. Finally in the last kilometre. The nearer the summit came, the more Jacques was suffering. In the last few hundred metres, he was losing time. At the top of the Puy it's 13 per cent. Poulidor should have attacked: he didn't. Poulidor didn't attack in the last 500 metres – it was Jacques who got dropped, and that's not the same thing.

Poulidor gained time but Anquetil still had a 55-second lead in Paris and won his last Tour. The writer Chris Sidwells said:

The race also ended the Anquetil era in Tour history. He could not face riding it the following year, and in 1966 he retired from the Tour with bad health – once he'd made sure that Poulidor could not win either.[n 2] Poulidor may not have managed to slay his dragon, in fact so bloodied was he by his battle that he never did win the Tour, but he did manage to wound his rival, and in so doing brought down the curtain on the rule of the first five-times winner – the first great super-champion of the Tour de France.[13]

Anquetil was first to win all three Grand Tours. He twice won the Giro d'Italia (1960, 1964) and won the Vuelta a España once (1963). He also won the season-long Super Prestige Pernod International four times, in 1961, 1963, 1965 and 1966 — a record surpassed only by Eddy Merckx.

Anquetil–Poulidor: the social significance

Anquetil unfailingly beat Raymond Poulidor in the Tour and yet Poulidor remained more popular. Divisions between their fans became marked, which two sociologists studying the impact of the Tour on French society say became emblematic of France old and new. The extent of those divisions is shown in a story, perhaps apocryphal, told by Pierre Chany, who was close to Anquetil:

The Tour de France has the major fault of dividing the country, right down to the smallest hamlet, even families, into two rival camps. I know a man who grabbed his wife and held her on the grill of a heated stove, seated and with her skirts held up, for favouring Jacques Anquetil when he preferred Raymond Poulidor. The following year, the woman became a Poulidor-iste. But it was too late. The husband had switched his allegiance to Gimondi. The last I heard they were digging in their heels and the neighbours were complaining.[4]

Jean-Luc Boeuf and Yves Léonard, in their study, wrote:

Those who recognised themselves in Jacques Anquetil liked his priority of style and elegance in the way he rode. Behind this fluidity and the appearance of ease was the image of France winning and those who took risks identified with him. Humble people saw themselves in Raymond Poulidor, whose face – lined with effort – represented the life they led on land they worked without rest or respite. His declarations, full of good sense, delighted the crowds: a race, even a difficult one, lasts less time than a day bringing in the harvest. A big part of the public therefore finished by identifying with the one who symbolised bad luck and the eternal position of runner-up, an image that was far from true for Poulidor, whose record was particularly rich.[14] Even today, the expression of the eternal second and of a Poulidor Complex is associated with a hard life, as an article by Jacques Marseille showed in Le Figaro when it was headlined "This country is suffering from a Poulidor Complex".[15][16]

Dauphiné and Bordeaux–Paris double

In 1965, Anquetil won the eight-day Alpine Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré stage race at 3pm, sat through two hours of interviews and receptions, took a chartered flight in a French Mirage fighter plane (allegedly organised by President Charles de Gaulle, a big admirer of his) to Bordeaux at 6.30pm and won the world's longest single-day classic, Bordeaux–Paris, the following day. The race started at night and continued from after dawn behind derny motorcycle pacers.

Anquetil was upset, said Géminiani, that Poulidor was always more warmly regarded even though he had never won the Tour. In 1965, when Poulidor was perceived to have received more credit for dropping Anquetil the previous year on the Puy-de-Dôme than Anquetil had for winning the whole Tour, Géminiani persuaded him to ride the Dauphiné Libéré and, next day, Bordeaux–Paris. That, he said, would end any argument over who was the greater.

Anquetil won the Dauphiné, despite bad weather which he disliked, at 3pm. After two hours of interviews and receptions he flew from Nîmes to Bordeaux. At midnight, he ate his pre-race meal and went to the start in the city's northern suburbs.

He could eat little during the night because of stomach cramp and was on the verge of retiring. Géminiani swore and called him "a great poof" to offend his pride and keep him riding.[17] Anquetil felt better as morning came and the riders dropped in behind the derny pacing motorcycles that were a feature of the race. He responded to an attack by Tom Simpson, followed by his own team-mate Jean Stablinski. Anquetil and Stablinski attacked Simpson alternately, forcing Simpson to exhaust himself, and Anquetil won at the Parc des Princes. Stablinski finished 57 seconds later just ahead of Simpson.[18]

The historian Dick Yates said:

It had been one of the hardest and closest derny-paced races in history but much more than that this double of Anquetil was one of the greatest exploits ever seen in cycling. At the Parc des Princes, Anquetil received the biggest ovation of his career, certainly much bigger than after any of his wins in the Tour. The race record was broken, Jacques was mobbed by reporters and photographers but he was tired and really had to get some rest. Few people realised it at the time but he had to make the long journey to Maubeuge in north-eastern France where the following day he was riding a criterium![19]

There are undenied rumours that the jet laid on to get Anquetil to Bordeaux was provided through state funds on the orders of President Charles de Gaulle. Géminiani mentions the belief in his biography, without denying it, saying the truth will come out when state records are opened.

Trofeo Baracchi

Anquetil's most humiliating race was the Trofeo Baracchi in Italy in 1962, when he had to be pushed by his partner, Rudi Altig, and was so exhausted that he hit a pillar before reaching the track on which the race finished.

The Trofeo Baracchi was a 111 km race for two-man teams. Anquetil, the world's best time-triallist, and Altig, a powerful rider with a strong sprint, were favourites. But things soon went wrong. The writer René de Latour wrote:

I got my stopwatch going again to check the length of each man's turn at the front. Generally in a race of the Baracchi type, the changes are very rapid, with stints of no more than 300 yards. Altig was at the front when I started the check — and he was still there a minute later. Something must be wrong. Altig wasn't even swinging aside to invite Anquetil through... Suddenly, on a flat road, Anquetil lost contact and a gap of three lengths appeared between the two partners. There followed one of the most sensational things I have ever seen in any form of cycle racing during my 35 years' association with the sport — something which I consider as great a physical performance as a world hour record or a classic road race win. Altig was riding at 30mph at the front — and had been doing so for 15 minutes. When Anquetil lost contact, he had to ease the pace, wait for his partner to go by, push him powerfully in the back, sprint to the front again after losing 10 yards in the process, and again settle down to a 30mph stint at the front. Altig did this not just once but dozens of times.[20]

The pair reached the track on which the race finished. The timekeeper was at the entrance to the stadium, so Anquetil finished. But instead of turning on to the velodrome, he rode straight on and hit a pole. He was helped away with staring eyes and with blood streaming from a cut to his head. The pairing nevertheless won by nine seconds.

Other races

Anquetil was not as successful in the classic single-day races but towards the end of his career he won:

- Gent–Wevelgem (1964)

- Liège–Bastogne–Liège (1966)

Anquetil finished in the top 10 in the world championship on six occasions, but second place in 1966 was the nearest he came to the rainbow jersey.[1]

In the other grand tours he also had remarkable success. He only entered the Vuelta a España twice and won it in 1963, which gave him the Vuelta-Tour double when he won the Tour a few months later. Then he placed on the podium six times in the Giro d'Italia, including victories in 1960 and 1964 and in 1964 he became only the second rider, after Fausto Coppi, to achieve the Giro-Tour double.

Riding style

Anquetil was a smooth rider, a beautiful pedalling machine according to the American journalist Owen Mulholland:

The sight of Jacques Anquetil on a bicycle gives credence to an idea we Americans find unpalatable, that of a natural aristocracy. From the first day he seriously straddled a top tube, "Anq" had a sense or perfection most riders spend a lifetime searching for. Between 1950, when he rode his first race, and nineteen years later, when he retired, Anquetil had countless frames underneath him, yet that indefinable poise was always there.[21]

The look was that of a greyhound. His arms and legs were extended more than was customary in his era of pounded post World War II roads. And the toes pointed down. Just a few years before, riders had prided their ankling motion, but Jacques was the first of the big gear school. His smooth power dictated his entire approach to the sport. Hands resting serenely on his thin Mafac brake levers, the sensation from Quincampoix, Normandy, appeared to cruise while others wriggled in desperate attempts to keep up.[21]

Physical attributes

| Height: | 1.76 m |

|---|---|

| Weight: | 70 kg (150 lb)[22] |

| Chest: | 95 cm |

| Arm circumference: | 27 cm |

| Calf circumference: | 32 cm |

| Thigh circumference: | 47 cm |

| Foot size: | 41 |

| Lung capacity: | 6 litres |

| Normal heart rate: | 48 |

| Heart rate after exercise: | 90 |

| Training: | 100–120 km, three times a week |

| Gym training: | 20 minutes, twice a week |

| Diet: | No restrictions other than sauces. A little wine with each meal. |

| Smoking: | A small cigar with meals in winter |

| Sleep: | Eight hours |

Raphaël Géminiani

Raphaël Géminiani had been Anquetil's rival as a rider; he became his strongest asset as his manager. Dick Yates wrote:

Raphaël embarked on a policy of trying to convince Jacques of the need to win more races as he certainly had the ability to do so... Anquetil had a very strong personality so he was not easily dominated but Géminiani had an even stronger one. He never gave up the task of trying to convince Jacques of the need for more panache, how a man of his talent should have an even bigger list of important wins.[19]

As a partnership they won four Tours de France, two Giri d'Italia, the Dauphiné-Libéré and then next day, Bordeaux–Paris. Géminiani said of him:

Today, everybody pays him homage. I nearly blow my top. I can still hear the way he was whistled when he rode. I think of the organisers of the Tour, who shortened the time trial[n 3] to make him lose. His home town of Rouen organises commemorations but, me, I haven't forgotten that it was in Antwerp that he made his farewell appearance. More than once, I saw him crying in his hotel room after suffering the spitting and insults of spectators. People said he was cold, a calculator, a dilettante. The truth is that Jacques was a monster of courage. In the mountains, he suffered as though he was damned. He wasn't a climber. But with bluffing, with guts, he bamboozled them all (il les a tous couillonnés).[23]

Honours

Anquetil was named France's champion of champions by L'Équipe in 1963. He was appointed Chevalier de l'Ordre national du Mérite in 1965 (cross of merit) and Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur on 5 October 1966.

Personal life

Anquetil was fascinated by astronomy and was delighted to meet Yuri Gagarin. The rational side of his character contrasted with his superstition. In the 1964 Tour de France, a fortune-teller called Belline predicted in France-Soir that Anquetil would die on or around the 13th day of the race. His wife Janine, knowing Anquetil's superstition, hid the paper but Anquetil found out, not least because he was sent clippings with unsigned letters.[24]

Jean-Paul Brouchon, leading cycling commentator at the news radio station France-Info, said of the day the forecast was supposed to come true:

During those dark hours, Anquetil refused to leave his room [the race was having a rest day]. Finally he agreed to go for a short car ride with Raphaël Géminiani [his team manager] and Janine, to join a party organised by Radio Andorra.[24]

A mixture of Anquetil's fear for the future and his enjoyment of living in the present led to newspaper pictures of the large meal and the wine that he drank that day. Next morning, still worried about the prediction and laden down by partying, he was dropped on the first hairpins of the Port d'Envalira.

He was famous for preparing for races by staying up all night drinking and playing cards, although the story seems to have increased with the telling. Nevertheless, his teammate, the British rider Vin Denson, has written in Cycling of exuberant parties during races. Denson has written, too, of Anquetil's scrupulous business arrangements with riders and others:

I always considered Jacques to be the very best professional", he said. "I admired him for the gentlemanly manner and charm with riders, the public and media. A more honest and sincere businessman and friend you would not find in any walk of life. His word was his all and was of great importance to him. He was a truly great man and champion who will be greatly missed and impossible to replace.[8]

The British journalist Alan Gayfer, former editor of Cycling said:

Jacques was a real Norman with the nuances of speech that make the Normans famous, they almost say Yes to mean No, and vice versa. I asked him when he was in London if Poulidor, who was often second to Jacques, could ever win the Tour de France: "Yes", he said, "but only if I am riding, and I would always finish ahead of him.[8]

But perhaps my finest memory of this lordly Frenchman came in 1966 at the Nürburgring, where a German official had been particularly rude to myself and other English journalists about going through one gate (the exit) to the press room instead of another 100 yards away (the entrance). We sat in delight, Sid Saltmarsh, Bill Long and me, not 20 yards from that 'Exit' gate, and watched as Jacques pulled up in his Ford Mustang, and proceeded to unload his bike from the back of the car. Yes, he did, not leaving it to mechanics. German official railed and cried, but all in vain. The seigniorial aspect came out oh so clearly, and Jacques did not merely ignore him, it was palpably as if the German did not exist at all. He left the car there, walked over to the riders' quarters pushing the gate open and the German with it. It was probably the finest comeuppance I shall ever see, and for that I shall remember Jacques for a long time.[8]

Dick Yates said:

"He had a deep love of the land and was at his happiest when driving a tractor. They [his wife and he] both acquired a taste for bridge parties which often continued late into the night. That Anquetil was a highly intelligent man there can be no doubt and he was the nearest thing to a true intellectual that cycling has ever produced."[25]

Anquetil married Janine Boeda on 22 December 1958. She had been married to Anquetil's doctor. The doctor, seeing a rival, sent his wife to live with friends.[26] Anquetil went to see her, disguised as a plumber,[26] and took her to Paris to buy clothes in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.[26]

Their marriage produced no children. Janine had two children, Alain and Annie, from her previous marriage. Janine had two failed pregnancies and Anquetil grew upset in 1970 that he was not a father.[26] The couple considered a surrogate mother before Janine thought of her daughter, Annie. Janine said: "We didn't use the parental authority that we could have had over her. It was a request that I addressed to her. Gently. Annie always had the choice of refusing."[n 4] Annie confirmed her mother's recollection.[26] She said:

When my mother asked that [I should become impregnated by my step-father, Anquetil].... I was totally breathtaken by the proposition.... But, mind, I accepted willingly. I have to admit that at the time, despite being 18 years old, I was in love with Jacques. And I knew that I pleased him. What do you expect? That's life. And that's how I found myself in his bed in the sacred mission of procreation.[26]

Anquetil, his wife and his wife's daughter began a ménage à trois[27] Annie said:

"Nobody thought it strange that Jacques Anquetil joined me in my bed each evening before returning to the marital bed beside my mother. Everybody was comfortable with it [Tout le monde était à l'aise]."[26]

Annie said she should have left the house after her daughter, Sophie, was born (in 2004, Sophie Anquetil published the book Pour l'amour de Jacques in which she confirmed what had been rumoured but what Anquetil had always tried to hide:[26] that she was Anquetil's daughter). Instead, she grew jealous of her own mother and demanded she leave instead.[26] When Janine refused, Annie left. To fill the gap, Janine invited her son, Alain, and his wife, Dominique, to return to live there. Anquetil began an affair with Dominique, to make Annie jealous.[26] Dominique had Anquetil's child but Annie still refused to return. Dominique still lives in the house, Les Elfes, where she organises conferences.[26] Janine and Anquetil divorced. Sophie moved in with Janine, although she lives now in Calenzana, near Calvi.[26] Both Janine and Dominique wrote their life story: neither mentioned the link between Sophie and Anquetil.[26]

Doping

Anquetil never hid that he took drugs and in a debate with a government minister on French television said only a fool would imagine it was possible to ride Bordeaux–Paris on just water. He and other cyclists had to ride through "the cold, through heatwaves, in the rain and in the mountains", and they had the right to treat themselves as they wished, he said, before adding: "Leave me in peace; everybody takes dope."[28] There was implied acceptance of doping right to the top of the state: Charles de Gaulle said: "Doping? What doping? Did he or did he not make them play the Marseillaise [the national anthem] abroad?"[29]

Anquetil won Liège–Bastogne–Liège in 1966. An official named Collard told him there would be a drugs test once he had got changed. "Too late", Anquetil said. "If you can collect it from the soapy water there, go ahead. I'm a human being, not a fountain." Collard said he would return half an hour later; Anquetil said he would have left for a dinner appointment 140 km away. Two days later the Belgian cycling federation disqualified Anquetil and fined him. Anquetil responded by calling urine tests "a threat to individual liberty" and engaged a lawyer. The case was never heard, the Belgians backed down and Anquetil became the winner.

Jacques had the strength – for which he was always criticised – to say out loud what others would only whisper. So, when I asked him 'What have you taken?' he didn't drop his eyes before replying. He had the strength of conviction.

Pierre Chany on Anquetil [30]

Anquetil argued that professional riders were workers and had the same right to treat their pains, as say, a geography teacher. But the argument found less support as more riders were reported to have died or suffered health problems through drug-related incidents, including the death of Tom Simpson, in the 1967 Tour de France.[8]

However, there was great support in the cyclist community for Anquetil's argument that, if there were to be rules and tests, the tests should be carried out consistently and with dignity. He said it was professional dignity, the right of a champion not to be ridiculed in front of his public, that led to his refusal to take a test in the centre of the Vigorelli track after breaking the world hour record.

The unrecognised time that Anquetil set that day was nevertheless broken by the Belgian rider Ferdinand Bracke. Anquetil was hurt that the French government had never sent him a telegram of congratulations but sent one to Bracke, who was not French. It was a measure of the unacceptability of Anquetil's arguments, as was the way he was quietly dropped from future French teams.

Anquetil and Britain

British fans voted Anquetil the BBC's international personality of 1964. He appeared with Tom Simpson from a studio in Paris. The Franco-American journalist René de Latour wrote:

In the studio we watched the proceedings in London, and while I cannot say Anquetil was keenly interested in the cricketing part, he was impressed with the general presentation which, however (like the stages of the 1964 Tour) he found a bit long. He was interested, though, to see Beryl Burton, and his old acquaintance Reg Harris pulling at his pipe in the invited audience.[31]

A few days later, Anquetil was named French sportsman of the year.

Anquetil was fascinated by British enthusiasm for time-trialling and in 1961 presented prizes at the Road Time Trials Council evening at the Royal Albert Hall to honour Beryl Burton and Brian Kirby.[8] The pair had won the women's and men's British Best All-Rounder competitions (BBAR) for, respectively, the highest average speed in a season over 25, 50 and 100 miles (women) and 50 and 100 miles (160 km) and 12 hours (men).

Alan Gayfer, the editor of Cycling at the time of Anquetil's death, wrote in appreciation:

It is strange to look back and see how this frail-looking young man burst on the scene in 1953. We had sent Ken Joy, the former BBAR, to challenge for the Grand Prix des Nations, then 140 kilometres long, and dragging through the hills of the Chevreuse valley. All over Paris they talked about this burly Englishman who had ridden 160 km in 4 hours and 6 minutes: and when it came to it, he was hammered by a 19-year-old, but a teenager with a will of iron that was to prove inflexible for the next 19 years.[8]

In 1964 Anquetil discussed riding a British 25 mile (40 km) race. Gayfer and Tom Simpson explained that the course would be flat and asked Anquetil how long the distance would take him. Anquetil, who could predict his time-trial times accurately, said 46 minutes. That was eight minutes faster than the British record standing to Bas Breedon at 54:23. It took until 1993 for the record to fall below Anquetil's estimation.

Anquetil asked £1,000 to compete and a London timber merchant called Vic Jenner said he would put up the money. Jenner had often put money into the sport. He died shortly afterwards, however, and the ride never happened.[32]

Anquetil took part, with Simpson, in an afternoon of exhibition racing at the Herne Hill track in South London, on 13 June 1964 – three weeks before starting in the 1964 Tour de France.

Anquetil rode on the Isle of Man in 1959, 1962 and in 1965, when he won the Manx Premier by beating Eddy Merckx into second place.[8]

Retirement and death

Anquetil rode his last race not in France, of which he still despaired for its preferring Poulidor, but on 27 December 1969 on the track at Antwerp. It happened, wrote L'Équipe "to the great indifference of the media."[n 5] He retired to a farm at Le Domaine des Elfes, La Neuville-Chant-d'Oisel, 17 km from Rouen. The château, formerly owned by Guy de Maupassant, was surrounded by 170 hectares.[26]

Anquetil was a correspondent for L'Équipe, consultant for Europe 1 and then on Antenne 2, a race director for Paris–Nice and the Tour Méditerranéen and in Canada, directeur sportif of French teams at world championships,[8] and a member of the managing committee of the Fédération Française de Cyclisme. His radio analyses were sharp and he gained notoriety in Belgium for telling Luis Ocaña, the Spanish rider living in France, how to beat Eddy Merckx.

He rode his bike only three times in retirement, saying he had already ridden enough. He rode the Grand Prix des Gentlemen in Nice, a race in which old riders were paired with current competitors; he went out for an afternoon with friends in Normandy; and he joined his daughter for a bike ride on her birthday. Other than that, he did not ride his bike after 1969.

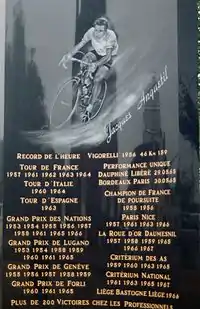

On 18 November 1987, Jacques Anquetil died of stomach cancer[33] in his sleep at 6 am at the St-Hilaire Clinic in Rouen. He had been there since 10 October. The clinic said: "His state of health had visibly deteriorated over the last hours and he died in his sleep after showing great courage throughout his illness."[8] Anquetil is buried beside the church in Quincampoix, north of Rouen, where a large black monument by the traffic lights lists his achievements. There is a further monument at the Piste Municipale in Paris, where the centre is named after him.

The Jacques Anquetil sports stadium at Quincampoix was dedicated in 1983. There are moves to open a museum in his memory.

The historian Richard Yates wrote:

He finally came to be respected as one of the most intelligent cyclists ever, but when he died in 1987 he was still to a large extent one of cycling's greatest enigmas. Raphaël Géminiani knew him better than anyone and he was such a perceptive man that his comments are particularly interesting. He said that Jacques was one of the most gifted riders of all time but this was hardly reflected by his record. He had won eight major Tours without once crossing the top of a mountain in the lead. His lack of offensive spirit made Géminiani mad with rage on countless occasions but he was always so incredibly stylish, absolute perfection.[5]

His inherent shyness can never fully explain his apparent cold indifference. His roots in the Normandy countryside may explain his love of the land but could not excuse his inability to even make a generous gesture. The hard life that his father had experienced could never pardon the economy of effort with which Jacques was obsessed. In the second half of his career he never made an effort which did not pay off 100 per cent. He reduced a race to a few simple calculations, a few danger men and a few places where it was necessary to make an effort. He spent most of the time at the back of the bunch and did not even know the name of most of the riders.[5]

The Tour visited Rouen on the 10th anniversary of Anquetil's death. There to remember his first victory in the race were his team-mates, Gilbert Bauvin, Louis Bergard, Albert Bouvet, André Darrigade, Jean Forestier, André Mahé, René Privat and Jean Stablinski. There, too, was the team car from Anquetil's first Tour, driven by the man behind the wheel that year, William Odin.[34]

Popular culture

Anquetil made an appearance in cartoon form in the animated movie The Triplets of Belleville (Les Triplettes de Belleville) (Belleville Rendez-vous in the British release).

The French film Amélie may contain an indirect reference to Anquetil. A long-lost box of souvenirs found by Amélie reminds an ageing estranged father of the time he cheered Federico Bahamontes' win of the 1959 Tour (Anquetil, a long-time rival of Bahamontes, came third). Amélie is later romantically pursued by Nino Quincampoix, who shares a rare surname with the village where Anquetil is buried.

Career achievements

Major results

- 1952

- 3rd

Team road race, Olympic Games

Team road race, Olympic Games - 8th Amateur road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 1953

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with Antonin Rolland)

- 1954

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 2nd Critérium des As

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with Louison Bobet)

- 5th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 7th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 5

- 9th Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 10th Overall Tour de l'Ouest

- 1955

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with André Darrigade)

- 6th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 9th Overall Tour du Sud-Est

- 1st Stage 6

- 1956

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 2nd

Individual pursuit, UCI Track World Championships

Individual pursuit, UCI Track World Championships - 8th Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 9th Overall Grand Prix du Midi Libre

- 1957

- 1st

Overall Tour de France

Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stage 3a (TTT), 3b, 9, 15b (ITT) & 20 (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 5a (ITT)

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Six Days of Paris (with André Darrigade and Ferdinando Terruzzi)

- 4th Trofeo Baracchi (with André Darrigade)

- 6th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 7th Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 1958

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stage 4 (ITT)

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with André Darrigade)

- 10th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 5a

- 10th Milan–San Remo

- 1959

- 1st

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

Overall Four Days of Dunkirk

- 1st Stage 4 (ITT)

- 1st Critérium des As

- 2nd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stages 2 (ITT) & 19 (ITT)

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 3rd Overall Tour de France

- 3rd Gent–Wevelgem

- 3rd Trofeo Baracchi (with André Darrigade)

- 5th Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 9th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 1960

- 1st

Overall Giro d'Italia

Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stage 9b (ITT) & 14 (ITT)

- 1st Critérium des As

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 3rd Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 8th Paris–Roubaix

- 8th Overall Tour de Romandie

- 1st Stage 4b (ITT)

- 9th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 1961

- 1st

Overall Tour de France

Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stages 1b (ITT) & 19 (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 6a (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Critérium National de la Route

Overall Critérium National de la Route - 1st Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 2nd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stage 9 (ITT)

- 3rd Mont Faron hill climb

- 4th Critérium des As

- 6th La Flèche Wallonne

- 10th Overall Tour de Romandie

- 1st Stage 2b (ITT)

- 1962

- 1st

Overall Tour de France

Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stages 8b (ITT) & 20 (ITT)

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Rudi Altig)

- 9th Critérium des As

- 1963

- 1st

Overall Tour de France

Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stage 6b (ITT), 10, 17 & 19 (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Vuelta a España

Overall Vuelta a España

- 1st Stage 1b (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 6a (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

Overall Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

- 1st Stage 6a (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Critérium National de la Route

Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 1st Stage 3 (ITT)

- 1st Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Critérium des As

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Raymond Poulidor)

- 1964

- 1st

Overall Tour de France

Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stage 9, 10b (ITT), 17 (ITT) & 22b (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Giro d'Italia

Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1st Stage 5 (ITT)

- 1st Gent–Wevelgem

- 1st Stage 1 Critérium National de la Route

- 3rd Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 3rd Critérium des As

- 6th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 3 (ITT)

- 7th Road race, UCI Road World Championships

- 1965

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice - 1st Bordeaux–Paris

- 1st

Overall Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

Overall Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

- 1st Stages 3, 5 & 7b (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Critérium National de la Route

Overall Critérium National de la Route

- 1st Stage 3 (ITT)

- 1st Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Jean Stablinski)

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 1st Grand Prix de Lugano

- 1st Critérium des As

- 1st Mont Faron hill climb

- 4th Overall Giro di Sardegna

- 7th Trofeo Laigueglia

- 8th Giro di Lombardia

- 1966

- 1st

Overall Paris–Nice

Overall Paris–Nice

- 1st Stage 8

- 1st

Overall Giro di Sardegna

Overall Giro di Sardegna - 1st Overall Super Prestige Pernod International

- 1st Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- 1st Grand Prix des Nations

- 2nd

Road race, UCI Road World Championships

Road race, UCI Road World Championships - 2nd Overall Volta a Catalunya

- 1st Stage 6b

- 3rd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 3rd Grand Prix de Lugano

- 4th Giro di Lombardia

- 1967

- 1st

Overall Volta a Catalunya

Overall Volta a Catalunya

- 1st Stage 7b (ITT)

- 1st

Overall Critérium National de la Route

Overall Critérium National de la Route - 2nd Trofeo Baracchi (with Bernard Guyot)

- 2nd Critérium des As

- 3rd Overall Giro d'Italia

- 7th Overall Giro di Sardegna

- 1968

- 1st Trofeo Baracchi (with Felice Gimondi)

- 4th Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- 5th Critérium des As

- 10th Overall Paris–Nice

- 1969

- 1st

Overall Tour of the Basque Country

Overall Tour of the Basque Country - 3rd Overall Paris–Nice

- 4th Overall Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

Grand Tour results timeline

| 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vuelta a España | – | – | – | – | – | DNF | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Giro d'Italia | – | – | 2 | 1 | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | 3 | 3 |

| Tour de France | 1 | DNF | 3 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | DNF | – |

World records

| Discipline | Record | Date | Velodrome | Track | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hour record | 46.159 km | 29 June 1956 | Vigorelli (Milan) | Indoor | [39] |

| 27 September 1967 | [n 6] |

Awards

- BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year: 1963[41]

See also

- List of doping cases in cycling

Notes

- Anquetil took the yellow jersey after the second half-stage (time trial) of the first day, Darrigade having won the first half-stage.

- In 1966 Anquetil prevented Poulidor from winning the Tour by putting his team-mate Lucien Aimar in a position to win.

- Anquetil was the dominant time-triallist of his period

- Non; nous n'avons pas abusé de l'ascendant que nous pouvions sur elle. C'est une prière que je lui ai adresseée. Gentiment. Annie avait toujours le choix de refuser. Anquetil le Sultan, Nouvel Observateur, France, 29 April 2004

- L'Équipe said Anquetil's farewell race was in Charleroi. Other reports agree that it was Antwerp.

- Anquetil set a record time in 1967 of 47.493 km but the record was never ratified by the UCI following Anquetil's refusal to take a post race doping control, and on 13 October the UCI voted not to allow the record.[40]

References

- "Jacques Anquetil Olympic Results". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Anquetil, Jacques (1966): En brûlant les étapes, Calmann-Levy, France

- L'Auto Cycle Sottevillais, Vélo, France, November 2007

- Woodland, Les (2007) The Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France, UK. ISBN 0224063189

- Yates, Richard (January 1997), Maître Jacques, Cycle News, UK

- Chany, Pierre (1988), La Fabuleuse Histoire de Cyclisme, Nathan, France. ISBN 2092864319

- Interview, Magazine 24, ORTF (television), France, 20 November 1963

- Cycling 26 November 1987

- Cycling, 7 October 1967, p. 4

- Ollivier, Jean-Paul (1999): Maillot Jaune, Reader's Digest Selection, France

- Dousset-Piel, l'Age de Bronze, Vélo, France November 2005

- Goddet, Jacques (1991): L'Équipée Belle, Robert Laffont, France

- Sidwells, Chris (2003) Golden Stages of the Tour de France, comp: Allchin, Richard and Bell, Adrian, Mousehold Press, UK

- The authors quote Milan–San Remo, the La Flèche Wallonne, the Vuelta a España and Paris–Nice.

- Le Monde, 16 April 2002, supplement page 3

- Boeuf, Jean Luc and Léonard Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France. ISBN 202058073X

- Video on YouTube

- Anquetil's impossible double Archived 2 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. ntlworld.com

- Cycling News, UK, December 1997, p. 19

- Sporting Cyclist, UK, undated cutting

- "Bikerace Info, Rider database, Jacques Anquetil". Archived from the original on 21 August 2008.

- These and other details published 1966 in En Brûlant les Étapes, Jacques Anquetil, published Calmann-Levy, France

- L'Express 19 June 2003

- Le Tour de France, Jean-Paul Brouchon, Balland-Jacob-Duvernet, 2000

- Cycling News, UK, December 1999, p20

- Anquetil le Sultan, Nouvel Observateur, France, 29 April 2004

- Anquetil, Sophie (2004) Pour l'Amour de Jacques, Grasset, France

- Cited in Les Miroirs du Tour, French television, 2003

- Cited L'Équipe Magazine 23 July 1994

- Penot, Christophe (1996) Pierre Chany, l'homme aux 50 Tours de France, Éditions Cristel, France. ISBN 2-9510116-0-1

- Sporting Cyclist, UK, 1965

- Cited "Cycling: the golden years", Springfield Press, UK

- "Cycling Hall of Fame.com". www.cyclinghalloffame.com.

- Cycling, "Anquetil anniversary celebrations", 5 July 1997

- "Jacques Anquetil (France)". The-Sports.org. Québec, Canada: Info Média Conseil. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "Palmarès de Jacques Anquetil (Fra)" [Awards of Jacques Anquetil (Fra)]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "Jacques Anquetil". Cycling Archives. de Wielersite. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Yates 2001, pp. 209−217.

- Hutchinson, Michael (15 April 2015). "Hour Record: The tangled history of an iconic feat". Cycling Weekly. Time Inc. UK. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- Howard 2008, pp. 209−217.

- Scott-Elliot, Robin (25 November 2000). "Protopopov and who?". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

Bibliography

- Fournel, Paul (2017). Anquetil, Alone: The legend of the controversial Tour de France champion. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-78283-298-0.

- Howard, Paul (2008). Sex, Lies and Handlebar Tape: The Remarkable Life of Jacques Anquetil, the First Five-Times Winner of the Tour de France. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-301-9.

- Yates, Richard (2001). Master Jacques: The Enigma of Jacques Anquetil. Norwich, UK: Mousehold Press. ISBN 978-1-874739-18-0.

External links

- Jacques Anquetil at Cycling Archives

- Jacques Anquetil at CyclingRanking.com

- Jacques Anquetil at Olympics.com

- Jacques Anquetil at Olympedia