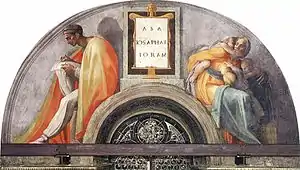

Jehoshaphat

Jehoshaphat (/dʒəˈhɒʃəfæt/; alternatively spelled Jehosaphat, Josaphat, or Yehoshafat; Hebrew: יְהוֹשָׁפָט, Modern: Yəhōšafat, Tiberian: Yŏhōšāp̄āṭ, "Yahweh has judged";[1] Greek: Ἰωσαφάτ, romanized: Iosafát; Latin: Josaphat), according to 1 Kings 15:24, was the son of Asa, and the fourth king of the Kingdom of Judah, in succession to his father. His children included Jehoram, who succeeded him as king. His mother was Azubah. Historically, his name has sometimes been connected with the Valley of Josaphat.[2]

| Jehoshaphat | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Judah | |

| Reign | c. 870 – 849 BCE |

| Predecessor | Asa |

| Successor | Jehoram |

| Issue | Jehoram |

| Father | Asa |

Reign

2 Chronicles chapters 17 to 21 are devoted to the reign of Jehoshaphat. 1 Kings 15:24[3] mentions him as successor to Asa, and 1 Kings 22:1-50[4] summarizes the events of his life. The Jerusalem Bible states that "the Chronicler sees Asa as a type of the peaceful, Jehoshaphat of the strong king".[5] According to these passages, Jehoshaphat ascended the throne at the age of thirty-five and reigned for twenty-five years. He "walked in the ways" of his father or ancestor, King David.[6] He spent the first years of his reign fortifying his kingdom against the Kingdom of Israel. His zeal in suppressing the idolatrous worship of the "high places" is commended in 2 Chronicles 17:6.[7][8]

In the third year of his reign, Jehoshaphat sent out priests and Levites over the land to instruct the people in the Law, an activity which was commanded for a Sabbatical year in Deuteronomy 31:10-13[9] (taking place in Jerusalem). Later reforms in Judah instituted by Jehoshaphat appear to have included further religious reforms,[10] appointment of judges throughout the cities of Judah[11] and a form of "court of appeal" in Jerusalem.[12][13] Ecclesiastical and secular jurisdictions, according to 2 Chronicles 19:11,[14] were by royal command kept distinct.[15]

The author of the Books of Chronicles generally praises his reign, stating that the kingdom enjoyed a great measure of peace and prosperity, the blessing of God resting on the people "in their basket and their store".[16]

Alliances

Jehoshaphat also pursued alliances with the kingdom of Israel in the North. Jehoshaphat's son Jehoram married Athaliah, daughter of king Ahab of Israel.[15] In the eighteenth year of his reign Jehosaphat visited Ahab in Samaria, and nearly lost his life accompanying his ally to the siege of Ramoth-Gilead. While Jehoshaphat safely returned from this battle, he was reproached by the prophet Jehu, son of Hanani, about this alliance.[8] We are told that Jehoshaphat repented, and returned to his former course of opposition to all idolatry, and promoting the worship of God and in the government of his people.[17]

Later it appears that Jehoshaphat entered into an alliance with Ahaziah of Israel, for the purpose of carrying on maritime commerce with Ophir.[18] He subsequently joined Jehoram of Israel in a war against the Moabites, who were under tribute to Israel. The Moabites were subdued, but seeing Mesha's act of offering his own son (and singular heir) as a propitiatory human sacrifice on the walls of Kir of Moab filled Israel with horror, and they withdrew and returned to their own land.[19]

Victory over Moabite alliance

According to Chronicles, the Moabites formed a great and powerful confederacy with the surrounding nations, and marched against Jehoshaphat.[20] The allied forces were encamped at Ein Gedi. The king and his people were filled with alarm. The king prayed in the court of the Temple, "O our God, will you not judge them? For we have no power to face this vast army that is attacking us. We do not know what to do; but our eyes are upon you."[21] The voice of Jahaziel the Levite was heard announcing that the next day all this great host would be overthrown. So it was, for they quarreled among themselves, and slew one another, leaving to the people of Judah only to gather the rich spoils of the slain. Soon after this victory Jehoshaphat died after a reign of twenty-five years at the age of sixty.[22] According to some sources (such as the eleventh-century Jewish commentator Rashi), he actually died two years later, but gave up his throne earlier for unknown reasons. As with his father Asa, a bonfire was lit in his honor.[23]

He also had the ambition to emulate Solomon's maritime ventures to Ophir, and built a large vessel for Tarshish. But when this boat was wrecked at Ezion-Geber he relinquished the project.[24]

In I Kings xxii. 43 the piety of Jehoshaphat is briefly dwelt on. Chronicles, in keeping with its tendency, elaborates this trait of the king's character. According to its report,[25] Jehoshaphat organized a missionary movement by sending out his officers, the priests, and the Levites to instruct the people throughout the land in the Law of YHWH, the king himself delivering sermons.

Underlying this ascription to the king of the purpose to carry out the Priestly Code, is the historical fact that Jehoshaphat took heed to organize the administration of justice on a solid foundation, and was an honest worshiper of Yhwh. In connection with this the statement that Jehoshaphat expelled the "Ḳedeshim" (R. V. "Sodomites") from the land (1 Kings 22:46) is characteristic; while 2 Chron. 19:3 credits him with having cut down the Asherot. The report[26] that he took away the "high places" (and the Asherim) conflicts with 1 Kings 22:44 (A. V. v. 43) and 2 Chron. 20:33. The account of Jehoshaphat's tremendous army (1,160,000 men) and the rich tribute received from (among others) the Philistines and the Arabs[27] is not historical. It is in harmony with the theory worked out in Chronicles that pious monarchs have always been the mightiest and most prosperous.[15]

Rabbinic literature

The question that puzzled Heinrich Ewald[28] and others, "Where was the brazen serpent till the time of Hezekiah?" occupied the Talmudists also. They answered it in a very simple way: Asa and Joshaphat, when clearing away the idols, purposely left the brazen serpent behind, in order that Hezekiah might also be able to do a praiseworthy deed in breaking it.[29][30]

Chronological notes

William F. Albright estimated the reign of Jehoshaphat to 873–849 BCE. Edwin R. Thiele held that he became coregent with his father Asa in Asa's 39th year, 872/871 BCE, the year Asa was infected with a severe disease in his feet, and then became sole regent when Asa died of the disease in 870/869 BCE, his own death occurring in 848/847 BCE.[31] So Jehoshaphat's dates are taken as one year earlier: co-regency beginning in 873/871, sole reign commencing in 871/870, and death in 849/848 BCE.

The calendars for reckoning the years of kings in Judah and Israel were offset by six months, that of Judah starting in Tishri (in the fall) and that of Israel in Nisan (in the spring). Cross-synchronizations between the two kingdoms therefore often allow narrowing of the beginning and/or ending dates of a king to within a six-month range. For Jehoshaphat, the Scriptural data allow the narrowing of the beginning of his sole reign to some time between Tishri 1 of 871 BCE and the day before Nisan 1 of 870 BCE. For calculation purposes, this should be taken as the Judean year beginning in Tishri of 871/870 BCE. His death occurred at some time between Nisan 1 of 848 BCE and Tishri 1 of that same year.

In popular culture

The king's name in the oath jumping Jehosaphat was likely popularized by the name's utility as a euphemism for Jesus and Jehovah. The phrase, spelled "Jumpin' Geehosofat", is first recorded in the 1865-1866 novel The Headless Horseman by the Irish-American novelist Thomas Mayne Reid.[32][33] The novel also uses "Geehosofat", standing alone, as an exclamation.[34] The longer version "By the shaking, jumping ghost of Jehosaphat" is seen in the 1865 novel Paul Peabody by the English journalist Percy Bolingbroke St John.[35]

Another theory is that the reference is to Joel 3:11-12,[36] where the prophet Joel says, speaking of the judgment of the dead, "Assemble yourselves, and come, all ye heathen, and gather yourselves together round about: thither cause thy mighty ones to come down, O LORD. Let the heathen be wakened, and come up to the valley of Jehoshaphat: for there will I sit to judge all the heathen round about."

In the 1956 Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies theatrical cartoon short, Yankee Dood It, based on the fairy tale of The Elves and the Shoemaker, Jehosephat figures prominently as an invocation to turn elves into mice. On the TV series Car 54, Where Are You?, the character Francis Muldoon cited his partner's frequent use of the phrase "Jumpin' Jehosephat!" as a source of annoyance in the episode entitled "Change Your Partners". The televised Batman live-action program of the 1960s also featured Robin, played by Burt Ward, uttering the phrase as an emphatic exclamation, and it was also incorporated into the talking alarm clock alarms voiced again by Burt Ward in 1974 in the "talking Batman & Robin alarm clock" made by Janex.

'Jehoshaphat!' was the standard curse-word used by Elijah Baley, protagonist of the first three science-fiction novels of Isaac Asimov's Robot series.

Another reference comes in Keno Don Rosa's The Invader of Fort Duckburg, a Scrooge McDuck Life and Times story. Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt exclaims 'Great Jumping Jehoshaphat!!' when confronted with Scrooge McDuck's illegal occupation of the fictitious Fort Duckburg, also in Disney’s 1963 animated film “The Sword in the Stone” Merlin uses “Jehoshaphat” to express alarm and annoyance. Furthermore, in Disney’s 1977 animated film “The Rescuers” Bernard explains “Jehoshaphat!” during the bayou chase scene.

Rapper MF Doom used the phrase "Jumpin' Jehosephat!" in his song "I Hear Voices", featured on the 2001 re-release of his 1999 debut album Operation: Doomsday.

References

- Khan, Geoffrey (2020). The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 1. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1783746767.

- J. D. Douglas, ed., The New Bible Dictionary (Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, MI, 1965) 604)

- Bible 1 Kings 15:24

- Bible 1 Kings 22:1–50

- Jerusalem Bible (1966), footnote a at 2 Chronicles 17

- Bible 2 Chronicles 17:3: NKJV. Alternatively this reference is translated as "his father's earlier days" in the Jerusalem Bible and the Revised Standard Version

- Bible 2 Chronicles 17:6

- Driscoll, James F., "Josaphat", The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910, accessed 8 January 2014

- Bible Deuteronomy 31:10–13

- Bible 2 Chronicles 19:3

- 2 Chronicles 19:5–7

- Bible 2 Chronicles 19:8–11

- Barnes, W. E. (1899), Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on 2 Chronicles 19, accessed 6 May 2020

- Bible 2 Chronicles 19:11

- Hirsch, E. G. (1906), Jehoshaphat, Jewish Encyclopedia

- Easton's Bible Dictionary: Jehoshaphat, accessed 3 May 2020

- Bible 2 Chronicles 19:4–11

- Bible 2 Chronicles 20:35–37

- Bible 2 Kings 3:4–27

- Bible 2 Chronicles 20

- Bible 2 Chronicles 20:12

- Bible 1 Kings 22:50

- Bible 2 Chronicles 21:19

- BibleI Kings xxii. 48 et seq.; II Chron. xx. 35 et seq.

- Bible II Chron. xvii. 7 et seq., xix. 4 et seq

- Bible 2 Chron. 17:6

- Bible II Chron. xvii. 10 et seq.

- "Gesch. des Volkes Israel," iii. 669, note 5

- Ḥul. 6b

- Hezekiah Jewish encyclopedia

- Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (3rd ed.; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983) 96, 97, 217.

- Reid, Mayne (1866). The Headless Horseman: A Strange Tale of Texas. London: Richard Bentley. p. 100. hdl:2027/uiug.30112002996210.

- "Jumping Jehosaphat", World Wide Words.

- Reid, Mayne (1866). The Headless Horseman: A Strange Tale of Texas. London: Richard Bentley. p. 61. hdl:2027/uiug.30112002996210.

- John, Percy Bolingbroke St (10 August 1865). "Paul Peabody: or, The apprentice of the world" – via Google Books.

- Bible Joel 3

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Emil, G. Hirsch (1904). "Jehoshaphat". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 86–87.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Emil, G. Hirsch (1904). "Jehoshaphat". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 86–87.