Jovan Vladimir

Jovan Vladimir or John Vladimir (Serbian Cyrillic: Јован Владимир;[lower-alpha 1] c. 990 – 22 May 1016) was the ruler of Duklja, the most powerful Serbian principality of the time,[1] from around 1000 to 1016. He ruled during the protracted war between the Byzantine Empire and the Bulgarian Empire. Vladimir was acknowledged as a pious, just, and peaceful ruler. He is recognized as a martyr and saint, with his feast day being celebrated on 22 May.[lower-alpha 2]

| Jovan Vladimir | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Duklja | |

A Serbian Orthodox icon of Prince Jovan Vladimir, who was recognized as a saint shortly after his death | |

| Reign | c. 1000 – 22 May 1016 |

| Predecessor | Petrislav |

| Successor | Dragimir (uncle) |

| Born | c. 990 |

| Died | 22 May 1016 Prespa, First Bulgarian Empire |

| Burial | Prespa |

| Spouse | Theodora Kosara |

| Father | Petrislav |

Jovan Vladimir had a close relationship with Byzantium but this did not save Duklja from the expansionist Tsar Samuel of Bulgaria, who conquered the principality around 1010 and took Vladimir prisoner. A medieval chronicle asserts that Samuel's daughter, Theodora Kosara, fell in love with Vladimir and begged her father for his hand. The tsar allowed the marriage and returned Duklja to Vladimir, who ruled as his vassal. Vladimir took no part in his father-in-law's war efforts. The warfare culminated with Tsar Samuel's defeat by the Byzantines in 1014 and death soon after. In 1016, Vladimir fell victim to a plot by Ivan Vladislav, the last ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire. He was beheaded in front of a church in Prespa, the empire's capital, and was buried there. He was soon recognized as a martyr and saint. His widow, Kosara, reburied him in the Prečista Krajinska Church, near his court in southeastern Duklja. In 1381, his remains were preserved in the Church of St Jovan Vladimir near Elbasan, and since 1995 they have been kept in the Orthodox cathedral of Tirana, Albania. The saint's remains are considered Christian relics, and attract many believers, especially on his feast day, when the relics are taken to the church near Elbasan for a celebration.

The cross Vladimir held when he was beheaded is also regarded as a relic. Traditionally under the care of the Andrović family from the village of Velji Mikulići in southeastern Montenegro, the cross is only shown to believers on the Feast of Pentecost, when it is carried in a procession to the summit of Mount Rumija. Jovan Vladimir is regarded as the first Serbian saint and the patron saint of the town of Bar in Montenegro. His earliest, lost hagiography was probably written sometime between 1075 and 1089; a shortened version, written in Latin, is preserved in the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja. His hagiographies in Greek and Church Slavonic were first published, respectively, in 1690 and 1802. The saint is classically depicted in icons as a monarch wearing a crown and regal clothes, with a cross in his right hand and his own head in his left hand. He is fabled to have carried his severed head to his place of burial.

Life

Duklja was an early medieval Serbian principality whose borders coincided for the most part with those of present-day Montenegro.[2] The state rose greatly in power after the disintegration of the early medieval Principality of Serbia that followed the death of its ruler, Prince Časlav, around 943. Though the extent of Časlav's Serbia is uncertain, it is known that it included at least Raška (now part of Central Serbia) and Bosnia. Raška had subsequently come under Duklja's political dominance, along with the neighboring Serbian principalities of Travunia and Zachlumia (in present-day Herzegovina and south Dalmatia).[3][4] The Byzantines often referred to Duklja as Serbia.[5]

Around 1000, Vladimir, still a boy, succeeded his father Petrislav as the ruler of Duklja.[6] Petrislav is regarded as the earliest ruler of Duklja whose existence can be confirmed by primary sources, which also indicate that he was in close relations with Byzantium.[6][7][8][9]

The principality consisted of two provinces: Zenta in the south and Podgoria in the north. A local tradition has it that Vladimir's court was situated on the hillock called Kraljič, at the village of Koštanjica near Lake Skadar, in the Krajina region of southeastern Montenegro.[10][11] Near Kraljič lie the ruins of the Prečista Krajinska Church (dedicated to Theotokos), which already existed in Vladimir's time.[12] According to Daniele Farlati, an 18th-century ecclesiastical historian, the court and residence of Serbian rulers once stood in Krajina.[13]

Vladimir's reign is recounted in Chapter 36 of the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, completed between 1299 and 1301;[14] Chapters 34 and 35 deal with his father and uncles. These three chapters of the chronicle are most likely based on a lost biography of Vladimir written in Duklja sometime between 1075 and 1089.[7][15] Both the chronicle and the 11th-century Byzantine historian John Skylitzes described Vladimir as a wise, pious, just, and peaceful ruler.[16][17]

Vladimir's reign coincided with a protracted war between the Byzantine Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025) and the ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire, Tsar Samuel (r. 980–1014). Basil II might have sought the support of other Balkan rulers for his fight against Samuel, and he intensified diplomatic contacts with Duklja for this purpose. A Serbian diplomatic mission, most likely sent from Duklja, arrived in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 992 and was recorded in a charter of the Great Lavra Monastery, written in 993.[18]

In 1004 or 1005, Basil recovered from Samuel the city of Dyrrhachium,[19] a major stronghold on the Adriatic coast,[20] south of Duklja. Since 1005, Basil had also controlled the coastal lands north and south of that city,[21] parts of the Byzantine Theme of Dyrrhachium.[22] Byzantium thus established a territorial contact with Prince Vladimir's Duklja, which was in turn connected to the Byzantine Theme of Dalmatia, consisting of Adriatic towns northwest of Duklja. The Republic of Venice, an ally of Byzantium, militarily intervened in Dalmatia in 1000 to protect the towns from attacks by Croats and Narentines. Venetian rule over Dalmatia on behalf of Basil was confirmed by the emperor in 1004 or 1005. Svetoslav Suronja, a Venetian ally, was crowned Croatian king. Venice, the Dalmatian towns, Croatia, and Vladimir's Duklja, were thus aligned in a compact pro-Byzantine bloc connected to Byzantium via Dyrrhachium.[19]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The close relations with Byzantium, however, did not help Prince Vladimir. Samuel attacked Duklja in 1009 or 1010, as part of his campaign aimed at breaking up that pro-Byzantine bloc, which could have threatened him.[19] Vladimir retreated with his army and many of his people to his fortress on a hill named Oblik, close to the southeastern tip of Lake Skadar.[6] According to the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, he performed a miracle there: the hill was infested with venomous snakes, but when he offered up a prayer to the Lord, their bites became harmless.[16]

Part of Samuel's army lay siege to the hill, and the remainder attacked the nearby coastal town of Ulcinj, which was part of the fortification system of the Theme of Dyrrhachium. Vladimir eventually surrendered, a decision the chronicle attributed to his wish to deliver his people from famine and the sword. He was sent to a prison in Samuel's capital of Prespa, located in western Macedonia.[6] Having failed to conquer Ulcinj, which received men and supplies by sea from Dalmatian towns, the tsar directed his forces towards Dalmatia. There, he burned the towns of Kotor and Dubrovnik, and ravaged the region as far northwest as Zadar. He then returned to Bulgaria via Bosnia and Raška.[19] A consequence of this campaign was the Bulgarian occupation of Duklja, Travunia, Zachlumia, Bosnia, and Raška.[6] Venetian, and indirectly Byzantine power in Dalmatia was weakened. Samuel had succeeded in breaking up the pro-Byzantine bloc.[19]

The chronicle states that while Vladimir languished in the Prespa prison, praying day and night, an angel of the Lord appeared to him and foretold that he would shortly be freed, but that he would die a martyr's death. His fate in captivity was described in a romantic story involving him and Theodora Kosara, Tsar Samuel's daughter. This is the chronicle's description of how they met:[23]

It came to pass that Samuel's daughter, Cossara, was animated and inspired by a beatific soul. She approached her father and begged that she might go down with her maids and wash the head and feet of the chained captives. Her father granted her wish, so she descended and carried out her good work. Noticing Vladimir among the prisoners, she was struck by his handsome appearance, his humility, gentleness and modesty, and the fact that he was full of wisdom and knowledge of the Lord. She stopped to talk to him, and to her his speech seemed sweeter than honey and the honeycomb.

Kosara then begged her father for Vladimir's hand, and the tsar granted her request. He restored his new son-in-law to the throne of Duklja.[23][24] In reality, the marriage was probably a result of Samuel's political assessment: he may have decided that Vladimir would be a more loyal vassal if he was married to his daughter.[3] Resolving thus the question of Duklja, Samuel could concentrate more troops in Macedonia and Thessaly, the main site of his conflict with Byzantium. The chronicle claims that the tsar also gave Vladimir the whole territory of Dyrrachium. The prince could in fact have been given a northern part of that territory, which was partially under Samuel's rule. A brief note on Vladimir by John Skylitzes may indicate that the prince also received some territory in Raška.[6][17] His paternal uncle Dragimir, ruler of Travunia and Zachlumia, who had retreated before Samuel's army, was given back his lands to rule, also as the tsar's vassal.[3][23]

Thereafter, as recorded in the chronicle, "Vladimir lived with his wife Cossara in all sanctity and chastity, worshipping God and serving him night and day, and he ruled the people entrusted to him in a Godfearing and just manner."[25] There are no indications that Vladimir took any part in his father-in-law's war efforts.[3] The warfare culminated in Samuel's disastrous defeat by the Byzantines in 1014, and on 6 October that same year, the tsar died of a heart attack.[18][26] He was succeeded by his son, Gavril Radomir, whose reign was short: his cousin Ivan Vladislav killed him in 1015 and ruled in his stead.[18] Vladislav sent messengers to Vladimir demanding his attendance at the court in Prespa, but Kosara advised him not to go and went there herself instead. Vladislav received her with honor and urged Vladimir to come as well, sending him a golden cross as a token of safe conduct. The chronicle relates the prince's reply:[25]

We believe that our Lord Jesus Christ, who died for us, was suspended not on a golden cross, but on a wooden one. Therefore, if both your faith and your words are true, send me a wooden cross in the hands of religious men, then in accordance with the belief and conviction of the Lord Jesus Christ, I will have faith in the life-giving cross and holy wood. I will come.

Two bishops and a hermit came to Vladimir, gave him a wooden cross, and confirmed that the tsar had made a pledge of faith on it. Vladimir kissed the cross and clutched it to his chest, collected a few followers, and set off for Prespa. As he arrived, on 22 May 1016, he went into a church to pray. When he exited the church, he was struck down by Vladislav's soldiers and beheaded.[6][27] According to Skylitzes, Vladimir believed Vladislav's pledge, told to him by the Bulgarian archbishop David. He then allowed himself to fall into Vladislav's hands, and was executed.[6][17] The motivation behind the murder is unclear. Since Samuel's defeat in 1014, the Bulgarians had been losing battle after battle, and Vladislav probably suspected or was informed that Vladimir planned to restore Duklja's alliance with Byzantium.[6][26] This alliance would be particularly disturbing for Tsar Vladislav because of the proximity of Duklja to Dyrrhachium, which was a target of the tsar's war efforts.[6]

In early 1018, Vladislav led an unsuccessful attack against Dyrrhachium, outside whose walls he found his death.[26] The chronicle asserts that Vladimir appeared before Vladislav when he dined in his camp outside Dyrrhachium, and slew him while he cried for help.[28] The same year, the Byzantine army—led by the victorious Basil—terminated the First Bulgarian Empire.[18] As Vladimir and Kosara had no children, his successor was his uncle Dragimir, the ruler of Travunia and Zachlumia. Accompanied by soldiers, he set off for Duklja to establish himself as its ruler, probably in the first half of 1018. When he came to Kotor, the town's inhabitants ambushed and killed him after inviting him to a banquet, and his soldiers returned to Travunia.[29][30] Duklja was not mentioned again in the sources until the 1030s. Some scholars believe that it was placed under direct Byzantine rule around 1018, while others believe it remained a Byzantine vassal state under an unknown native ruler.[2]

Sainthood

Saint Jovan Vladimir | |

|---|---|

A Greek icon of Saint Jovan Vladimir (Ἰωάννης ὁ Βλαδίμηρος in Greek) | |

| Wonderworker, Great Martyr, Myrrh‑gusher | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine |

|

| Feast | 22 May[lower-alpha 2] |

| Attributes | Cross, his own severed head, crown, and regal clothes |

| Patronage | Bar, Montenegro |

Jovan Vladimir was buried in Prespa, in the same church in front of which he was martyred.[24] His relics soon became famous as miraculously healing, attracting many people to his tomb. Shortly after his death he was recognized as a martyr and saint, being commemorated on 22 May, his feast day.[27][31][32] At that time, saints were recognized without any formal rite of canonization.[33] Vladimir was the first ruler of a Serbian state who was elevated to sainthood.[6] The rulers from the Nemanjić dynasty, who reigned over the Serbian state which grew around Raška, would almost all be canonized—starting with Nemanja, the saintly founder of the dynasty.[15]

Several years after his burial, Kosara transported the remains to Duklja. She interred him in the Prečista Krajinska Church, near his court, in the region of Skadarska Krajina. The relics drew many devotees to the church, which became a center of pilgrimage. Kosara did not remarry; at her request, she was interred in Prečista Krajinska, at the feet of her husband.[24][34] In around 1215—when Krajina was under the rule of Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanjić—the relics were presumably removed from this church and transported to Dyrrhachium by the troops of Michael I, the despot of Epirus. At that time Despot Michael had briefly captured from Serbia the city of Skadar, which is only about 20 km (12 mi) east of the church. Jovan Vladimir was mentioned as the patron saint of Dyrrhachium in a Greek liturgical text.[24][35]

In 1368 Dyrrhachium was taken from the Angevins by Karlo Thopia, an Albanian lord.[36] In 1381 he rebuilt, in Byzantine style, a church ruined in an earthquake in the narrow valley of the stream Kusha, a tributary of the Shkumbin River—near the site of the town of Elbasan in central Albania (built in the 15th century). The church was dedicated to Saint Jovan Vladimir, as the inscription which Thopia placed above its south entrance declared in Greek, Latin, and Serbian. The saint's relics were kept in a reliquary, a wooden casket, which was enclosed in a shrine, 3 m (9.8 ft) in height, within the church.[37]

Serbian scholar Stojan Novaković theorized that Vladimir was buried near Elbasan immediately after his death. Novaković conjectured that the earthquake which ruined the old church happened during Thopia's rule, and that Thopia reinstated the relics in the rebuilt church. If Vladimir was previously buried in Duklja, Novaković reasoned, he would not be absent, as he was, from Serbian sources written during the reign of the Nemanjić dynasty, who ruled over Duklja (later named Zeta) from 1186 to 1371. Novaković did not consider the idea that the relics might have been removed from Duklja to Dyrrhachium in around 1215.[37] He commented on the chronicle's account that Kosara transported Vladimir's body "to a place known as Krajina, where his court was":[27] While his court was possibly in the region of Krajina before his captivity, after he married Kosara it could have been near Elbasan, in the territory of Dyrrachium he received from Tsar Samuel. He was interred near the latter court, which was replaced in the chronicle with the former.[37]

An Orthodox monastery grew around the church near Elbasan, and became the center of veneration of Saint Jovan Vladimir, which was limited to an area around the monastery. In the latter half of the 15th century, the territory of present-day Albania was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, in which Islam was the privileged religion. After losing the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Ottomans went on the defensive in Europe. In the climate of revival of Christianity in the Ottoman Empire, a hagiography of the saint and a service to him were written in Greek in 1690 at the monastery.[38] It stood under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid, which became a notable spiritual and artistic force during the leadership of Archbishop Joasaph from 1719 to 1745. In this period, the veneration of Saint Jovan Vladimir was promoted in southern Albania and western Macedonia, as well as beyond the archbishopric, in Bulgaria and among the Serbs in the Kingdom of Hungary.[39]

The monastery became the see of the newly founded Archbishopric of Dyrrhachium in the second half of the 18th century.[35] In more recent times the monastery fell into disrepair, and in the 1960s it was closed by Albania's Communist authorities;[40] in 1967 the reliquary with the saint's relics was moved to St Mary's Church in Elbasan.[41] The dilapidated monastery was returned to the Church in the 1990s. The restoration of its church and other buildings was completed in 2005.[40][42] Since around 1995 the relics have been kept in the Orthodox cathedral of Tirana, the capital of Albania, and are brought back to the monastery only for the saint's feast day.[40][43]

Each year on the Feast of Saint Jovan Vladimir, a great number of devotees come to the monastery,[44] popularly known as Shingjon among Albanians. In the morning, the reliquary is placed at the center of the church under a canopy, before being opened. After the morning liturgy has been celebrated, chanting priests carry the reliquary three times around the church, followed by the devotees, who hold lit candles. The reliquary is then placed in front of the church, to be kissed by the believers. The priests give them pieces of cotton that have been kept inside the reliquary since the previous feast. There are numerous stories about people, both Christians and Muslims, who were healed after they prayed before the saint's relics.[45]

On the eve of the Feast of Saint Jovan Vladimir, an all-night vigil is celebrated in the churches dedicated to the saint, as is celebrated in other Orthodox churches on the eves of their patron saints' feasts.[46] The liturgical celebration of Vladimir's feast day begins on the evening of 21 May,[lower-alpha 2] because, in the Orthodox Church, the liturgical day is reckoned from one evening to the next. Despite the name of the service, the all-night vigil is usually not held throughout the entire night, and may last only for two hours.[47] In the Church of St Jovan Vladimir near Elbasan, it lasts from 9:00 p.m. to 3:00 a.m.[48] Hymns either to Jovan Vladimir or to another saint whose commemoration falls on 22 May, are chanted, on that liturgical day, at set points during services in all Orthodox churches.[49]

Saint Jovan Vladimir is the patron saint of the modern-day town of Bar in south Montenegro,[50][51] built at its present location in 1976 about 4 km (2.5 mi) from the site of the old town of Bar, which was destroyed in a war and abandoned in 1878.[52] A religious procession celebrating the saint passes on his feast day through the town's streets with church banners and icons. The procession is usually led by the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral.[51] The bronze sculpture King Jovan Vladimir, 4 m (13 ft) in height, was installed at the central square of Bar in 2001; it is a work by sculptor Nenad Šoškić.[53] Although Vladimir was only a prince, he is referred to as "king" in the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja.[16] He is called the Holy King in southeastern Montenegro, and hence the hillock thought to be the site of his court is named Kraljič (kralj means "king").[10]

Cross of Vladimir

A cross, held by tradition to be the one that Jovan Vladimir received from Ivan Vladislav, and had in his hands when he was martyred, is a highly valued relic. It is under the care of the Andrović family from the village of Velji Mikulići near Bar and, according to the Androvićs, has been for centuries. The cross is made of yew wood plated with silver, with a brass ball attached to its lower arm, into which a stick is inserted when the cross is carried. The cross is 45 cm (18 in) high, 38 cm (15 in) wide, and 2.5 cm (1.0 in) thick.[54][55]

According to Russian scholars Ivan Yastrebov and Pavel Rovinsky, the cross was originally kept in the Prečista Krajinska Church, in which Kosara had interred Vladimir.[56][57] The peak of Islamization of the Krajina region was reached at the end of the 18th century.[56] The church was torn down, though it is uncertain when and by whom, but the cross was preserved by the people of the region.[57] They believed that it could protect against evil and ensure a rich harvest, and kept it as sacred, although they had converted to Islam.[54] The cross was later taken from them by the neighboring clan of Mrkojevići. As they too converted to Islam, they entrusted the cross to the Andrović family—their Orthodox Christian neighbors.[56][57] The Mrkojevići considered it more appropriate for the cross to be kept in a Christian home, rather than in a Muslim one.[57]

The cross, followed by a religious procession, is carried each year on the Feast of Pentecost from Velji Mikulići to the summit of Mount Rumija. The procession is preceded by a midnight liturgy in the village's Church of St Nicholas. After the liturgy, the ascent begins up a steep path to the 1,593 m (5,226 ft) summit of Rumija. The cross, carried by a member of the Andrović family, leads the procession, followed by an Orthodox priest and the other participants. Catholics and Muslims of the region have traditionally participated in the procession. It is carefully observed that no one precedes the cross; to do so is considered a bad omen. The ascending devotees sing:[54]

Krste nosim, |

I carry the cross, |

.jpg.webp)

In the past, the standard-bearer of the Mrkojevići clan, a Muslim, walked next to the cross with a flag in his left and a knife in his right hand, ready to use it if anyone attempted to take the cross. The clan especially feared that the participants from Krajina might try to recover the sacred object. At the end of the 19th century the number of Muslims in the procession dropped as their religious and political leaders disapproved of their participation in it.[58] After World War II, Yugoslavia's socialist government discouraged public religious celebrations, and the procession was not held between 1959 and 1984.[54]

Tradition has it that a church dedicated to the Holy Trinity stood at the summit until it was razed by the Ottomans; in another version, the church crumbled after a boy and a girl sinned within. Before 2005, there was a custom to pick up a stone at a certain distance from the peak and carry it to the supposed site of the church in the belief that when a sufficient quantity of stones were collected, the church would rebuild itself.[54] A new church dedicated to the Holy Trinity was consecrated on the site by the Serbian Orthodox Church on 31 July 2005.[59]

The procession arrives at the peak before dawn, and at sunrise the morning liturgy begins. After prayers have been offered, the procession goes back to Velji Mikulići, again following the cross. The participants would formerly gather on a flat area 300 m (980 ft) from the peak,[54] where they would spend some five or six hours in a joyous celebration and sports, and have a communal meal.[58] On the way back, some people pick the so-called herb of Rumija (Onosma visianii), whose root is reputed for its medicinal properties. The procession ends at the Church of St Nicholas, and folk festivities at Velji Mikulići continue into the night. Until the next Feast of Pentecost, the cross is kept at a secret location. It was formerly known only to two oldest male members of the Andrović family,[54] and since around 2000 the Androvićs have appointed a committee to keep the cross.[55]

Hagiography and iconography

The oldest preserved hagiography of Saint Jovan Vladimir is contained in Chapter 36 of the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja. This chronicle, written in Latin, was completed between 1299 and 1301 in the town of Bar, then part of the Serbian Kingdom. Its author was Rudger, the Catholic Archbishop of Bar, who was probably of Czech origin.[14] He wrote Chapter 36 as a summary of an older hagiography of Vladimir, written in Duklja most likely sometime between 1075 and 1089. This is the period when Duklja's rulers from the Vojislavljević dynasty endeavored to obtain the royal insignia from the Pope, and to elevate the Bishopric of Bar to an archbishopric. They represented Prince Vladimir as the saintly founder of their dynasty;[15] they were, according to the chronicle, descendants of his uncle Dragimir.[30] The Vojislavljevićs succeeded in those endeavors, though Vladimir was not recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.[15] Despite its hagiographic nature, Chapter 36 contains a lot of reliable historical data.[6] Chapters 34 and 35, which deal with Vladimir's father and uncles, are probably based on the prologue of the 11th-century hagiography.[7] Chapters 1–33 of the chronicle are based on oral traditions and its author's constructions, and are for the most part dismissed by historians.[6][7]

The hagiography in the chronicle is the source for the "Poem of King Vladimir" composed in the 18th century by a Franciscan friar from Dalmatia, Andrija Kačić Miošić. The poem is part of Miošić's history of the South Slavs in prose and verse, written in the Croatian vernacular of Dalmatia. This book was first printed in Venice in 1756 and was soon read beyond Dalmatia, including Serbia and Bulgaria (then under Ottoman rule, as was most of the Balkans). The "Poem of King Vladimir" is composed in a manner derived from the style of the South Slavic oral epics. It describes Vladimir's captivity in Bulgaria, the love between Kosara and him, Tsar Samuel's blessing of their marriage, and their wedding. It concludes with the newlyweds setting off for Vladimir's court, which Miošić places in the Herzegovinian city of Trebinje.[60][61]

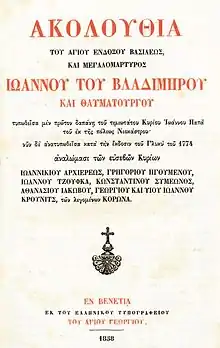

The Greek akolouthia on Saint Jovan Vladimir, containing his hagiography, prayers to him, and hymns to be chanted in church services on his feast day, was printed in Venice in 1690. The book was reprinted with small changes in 1774 and 1858. It was written from oral traditions by the deputy of the Orthodox Archbishop of Ohrid, Cosmas, who resided at the Monastery of St Jovan Vladimir, near Elbasan. Copies of the book were distributed to other Orthodox churches and individuals. The akolouthia was also published in 1741 in Moscopole, an Aromanian center in southeastern Albania, as part of a compilation dedicated to saints popular in that region.[38] A shorter hagiography of the saint, based on his life contained in this akolouthia, was included in the Synaxarium composed by Nicodemus the Hagiorite, printed in Venice (1819) and Athens (1868).[37][62] Cosmas's text was the basis for the Church Slavonic akolouthias on the saint, which appeared in Venice (1802) and Belgrade (1861). The latter was printed as part of the third edition of Srbljak, a compendium of akolouthias on Serb saints, published by the Serbian Orthodox Church.[38] The saint's life in English, translated from Church Slavonic, appeared in the book Lives of the Serbian Saints, published in London in 1921 by the Anglican Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.[63]

In Cosmas's writing, the saint was named "Jovan from Vladimir"; his father was Nemanja (historically, Grand Prince of Raška from 1166 to 1196), and his grandfather was Simeon (Bulgarian Tsar from 893 to 927). He married a daughter of Samuel, the tsar of Bulgaria and Ohrid. He succeeded his father as emperor of Albania, Illyria, and Dalmatia. After Byzantine Emperor Basil defeated Tsar Samuel, Emperor Jovan defeated Basil. He also fought against the Bogomil and Messalian heretics. From his early youth, Jovan Vladimir longed for the Kingdom of God. After he was married, he prayed day and night, and abstained from intercourse with his wife. She was a heretic like her brother, whom she incited to kill Jovan. When the two brothers-in-law rode together, accompanied by soldiers, the heretic suddenly struck Jovan with a sword at a mountain pass named Derven, but could not cut him. Only when Jovan gave him his own sword was the murderer able to cut off his head. Jovan caught it in the air and rode on to the church he had built near Elbasan. There he put his head down, saying, "Lord Jesus Christ, in your hands I place my spirit," and died; it was AD 899. He was buried in the church, which then became the scene of many miracles.[38] The saint's beneficent power is described in the hagiography:[64]

|

ἐν ἑνὶ τόπῳ ὑπάρχει, καὶ ἐν ὅλω τῷ κόσμω ἐπικαλούμενος διάγει. ἐκεῖ ἐν τοῖς Οὐρανοῖς Χριστῷ τῷ Θεῷ παρίσταται, καὶ τῶν ἐνταῦθα οὐδ᾿ ὅλως ἀφίσταται. ἐκεῖ πρεσβεύει, καὶ ὧδε ἡμῖν θριαμβεύει. ἐκεῖ λειτουργεῖ, καὶ ὧδε θαυματουργεῖ. κοιμῶνται τὰ Λείψανα, καὶ κηρύττει τὰ πράγματα. ἡ γλῶσσα σιγᾷ, καὶ τὰ θαύματα κράζουσι. Τίς τοσαῦτα εἶδεν; ἢ τίς ποτε ἢκουσεν; ἐν τῷ τάφῳ τὰ ὀστέα κεκλεισμένα, καὶ ἐν ὅλῳ τῷ Κόσμῳ τὰ τεράστια θεωρούμενα. |

|

According to Vladimir's life in Church Slavonic, he succeeded his father Petrislav as the ruler of Serbian lands; he ruled from the town of Alba. He was captured and imprisoned by the Bulgarian ruler Samuel. After marrying Samuel's daughter Kosara, he returned to his country. Emperor Basil, having overcome Bulgaria, attacked the Serbian lands, but Vladimir repulsed him. Basil advised the new Bulgarian ruler, Vladislav, to kill Vladimir by trickery. Vladislav invited Vladimir to visit him, as if to discuss the needs of their peoples. When Kosara came to him instead, Vladislav received her with apparent kindness; therefore Vladimir came as well. Vladislav was able to cut off his head only after Vladimir gave him his own sword. The saint then carried his severed head to the church he had built near Alba, and died there; it was AD 1015. He was buried in the church. During Vladislav's siege of Dyrrachium, Vladimir appeared before his murderer when he dined, and slew him while he cried for help. The saint's relics then gushed myrrh, curing various illnesses.[63][65] The kontakion which is contained, among other hymns, in the Church Slavonic akolouthia published as part of Srbljak, praises the saint:[66]

|

Ꙗ́кѡ сокро́вищє многоцѣ́нноє и исто́чникъ то́чащъ зємни́мъ то́ки нєдѹ́ги ѿчища́ющыѧ։ и на́мъ подадє́сѧ тѣ́ло твоє̀ свѧщє́нноє, болѣ́знємъ разли́чнимъ пода́ющє исцѣлє́нїе и благода́ть божєствє́ннѹю притєка́ющимъ къ нє́мѹ, да зовє́мъ ѥмѹ́։ ра́дѹйсѧ кнѧ́жє Влади́мирє. |

|

.PNG.webp)

In a Bulgarian liturgical book written in 1211, Vladimir was included in a list of tsars of the First Bulgarian Empire: "To Boris, . . . Samuel, Gavril Radomir, Vladimir, and Vladislav, ancient Bulgarian tsars, who inherited both the earthly and the heavenly empires, Memory Eternal."[67] According to the earliest work of Bulgarian historiography composed in 1762 by Paisius of Hilendar,[68] Vladimir, also named Vladislav, was a Bulgarian tsar and saint. His father was Aron, Tsar Samuel's brother. His wife and her brother murdered him because of his pure life and Orthodox faith. Paisius combined Ivan Vladislav and Jovan Vladimir into one character attributed with Vladislav's parentage and Vladimir's sainthood.[69]

An important model for the iconography of Saint Jovan Vladimir is an engraving in the 1690 edition of the Greek akolouthia. It is a work by Venetian engraver Isabella Piccini.[39] She depicted the saint with a mustache and short beard, wearing a cloak and a crown inscribed with lilies, holding a cross in his right hand, and his severed head in his left hand.[38] A portable icon in Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula, dated around 1700, shows the saint mounted on horseback.[39]

An icon of Saints Marina and Jovan Vladimir, dated 1711, is part of the iconostasis of the Monastery of St Naum near Ohrid in western Macedonia. The icon's position on the iconostasis indicates that Vladimir was an important figure of local veneration.[39] He was often depicted in the company of Saints Clement and Naum in Macedonian churches.[34] A number of 18th-century painters from central and southern Albania painted the saint in churches of the region, especially in the area of Moscopole.[70] A portable icon of the saint was created in 1739 at the Ardenica Monastery in southwestern Albania. It depicts him seated on a throne, surrounded by twelve panels showing scenes of his life and miracles.[39] Saint Jovan Vladimir is represented on frescos in three monasteries of Mount Athos: Hilandar, Zograf, and Philotheou; and three Bulgarian monasteries: Rila, Troyan, and Lozen.[34]

Hristofor Žefarović, an artist from Macedonia, painted the frescos in the rebuilt church of the Serbian Monastery of Bođani, in the Bačka region (then part of the Kingdom of Hungary) in 1737. There, he depicted Jovan Vladimir in a row of six Serb saints, wearing a crown and sceptre, clad in a full-length tunic, loros (a type of stole), and chlamys. In the same row stands another Serb saint from present-day Montenegro, Stefan Štiljanović.[71] Žefarović's frescos in Bođani are regarded as the earliest work showing Baroque traits in the Serbian art.[72] Žefarović created in 1742 in Vienna a copperplate with scenes of the saint's life and miracles. Its printed impressions were disseminated to many Orthodox Christian homes in the Balkans. The same author included him among the rulers and saints whom he illustrated in his Stemmatographia.

A lithography in the 1858 edition of the Greek akolouthia shows the saint wearing a crown with a double lily wreath, his right foot on a sword. He holds a cross, a sceptre, and an olive branch in his right hand, while his crowned severed head is in his left hand. He wears an ermine cloak and a robe with floral designs, adorned with large gems surrounded by pearls. The Greek text beneath the illustration names the saint as Jovan Vladimir, the pious Emperor of all Albania and Bulgaria, the graceful Wonderworker and Great Martyr, and true Myrrh-gusher.[38][73] In his hagiography included in the Synaxarium of Nicodemus the Hagiorite, the saint is referred to as Emperor of the Serbs (τῶν Σέρβων βασιλεύς). [34]

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Legends

Several legends about Jovan Vladimir have been recorded in western Macedonia. One has it that, after he was beheaded, he brought his head to the Monastery of St John of Bigor. On a hill above the village of Pesočani in the Municipality of Debarca, there is a locality called Vladimirovo, where some ruins can be seen. The locals claim that it is where Vladimir was born and later brought his severed head.[37] The Church of St Athanasius near Pesočani, now ruined, is reputed to have been built by Vladimir. People from the region gathered there each year on the eve of his feast day. They lit candles on the remains of the church's walls and prayed to the saint.[74] Tradition has it that the Monastery of St Naum had a bell tower named after the saint, in the foundation of which a portion of his relics was placed.[75]

In the western fringe of Macedonia, which is now part of Albania, Jovan Vladimir was remembered as a saintly ruler, cut down by his father-in-law, an emperor, who believed the slanderous accusation that he was a womanizer. The enraged emperor, accompanied by soldiers, found Vladimir on a mountain pass named Qafë Thanë (also known as Derven), on the road between the Macedonian town of Struga and Elbasan. He struck his son-in-law with a sword, but could not cut him. Only when Vladimir gave him his own sword was the emperor able to cut off his head. Vladimir took his severed head and went towards the site of his future church. There stood an oak, under which he fell after the tree bowed down before him. The saint was interred in the church which was subsequently built at that place and dedicated to him.[75]

_detail2.jpg.webp)

_detail.jpg.webp)

According to a legend recorded in the Greek hagiography, Jovan Vladimir built the church near Elbasan. Its location, deep in a dense forest, was chosen by God, and an eagle with a shining cross on its head showed it to Vladimir. After the saint was decapitated, he brought his head to the church, and was buried inside. A group of Franks once stole the casket with his miraculous relics. The casket turned out to be extremely heavy, breaking the backs of the hinnies on which the Franks carried it. They eventually placed it in the Shkumbin River to take it to sea, but the river flooded, and the casket—radiating light—went back upstream towards the church. The local inhabitants took it out of the water and returned it to the church in a festive procession.[38]

A group of thieves stole, on a summer day, horses that belonged to the Monastery of St Jovan Vladimir. When they came to the nearby stream of Kusha to take the horses across, it appeared to them like an enormous river. They moved away from it in fear, but when they looked back from a distance, the stream appeared small. As they approached it again, the Kusha again became huge and impassable. After several such attempts to cross the stream, the thieves realized that this was a miracle of the saint, so they released the monastery's horses and ran away in horror.[45]

In the 19th century, a possible legend about Prince Vladimir was recorded by Branislav Nušić in the city of Korçë, in southeastern Albania. Ruins on a hilltop above Korçë were said to be the remnants of the court of a Latin (Catholic) king, whose kingdom neighbored the state of an Orthodox emperor. The king asked for the hand of the emperor's daughter, who agreed to become the king's wife only if he constructed an Orthodox church. The king did so, and she married him, but on the first night of their marriage, she killed him. She then became a nun, and the king's body was taken somewhere—he was not buried near his court.[37] Macedonian Slavs inhabiting Saint Achillius Island in the Small Prespa Lake in Greece told of an emperor named Mirče. He lived on their island, where he was killed by a cousin of his out of jealousy, and his body was taken via Ohrid to Albania.[37]

Notes

Footnotes

- The name in Greek: Ἰωάννης ὁ Βλαδίμηρος (Iōannīs o Vladimīros); in Bulgarian: Йоан Владимир (Yoan Vladimir) or Иван Владимир (Ivan Vladimir); in Albanian: Gjon Vladimiri or Joan Vladimiri.

- Some Orthodox Churches use the Julian calendar rather than the Gregorian used in the West. Since 1900, the Julian calendar is 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar, and this difference will remain until 2100. During this period, 22 May in the Julian calendar—the Feast of Saint Jovan Vladimir for those Churches—corresponds to 4 June in the Gregorian calendar.

Citations

- Fine 1991, pp. 193, 202.

- Fine 1991, pp. 202–3

- Fine 1991, pp. 193–95

- Živković 2006, pp. 50–57

- Ostrogorsky 1998, pp. 293, 298

- Živković 2006, pp. 66–72

- Живковић 2009, pp. 260–62

- Živković 2006, "Стефан Војислав".

- Van Antwerp Fine 1991, p.203.

- Jovićević 1922, p. 14

- Milović & Mustafić 2001, p. 54

- Jireček 1911, p. 205

- Farlati 1817, p. 13 (col 2)

- Живковић 2009, p. 379

- Живковић 2009, pp. 267–69

- Rudger 2010, para. 1

- Skylitzes & Cedrenus 1839, p. 463

- Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 273–75

- Živković 2002, pp. 9–24

- Stephenson 2005, p. 67

- Stephenson 2005, p. 70

- Stephenson 2005, pp. 160–62.

- Rudger 2010, para. 2

- Jireček 1911, pp. 206–7

- Rudger 2010, para. 3

- Fine 1991, pp. 198–99

- Rudger 2010, para. 4

- Rudger 2010, para. 5

- Živković 2006, p. 76

- Живковић 2009, p. 272

- "Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἰωάννης ὁ Θαυματουργός τοῦ Βλαδιμήρου" (in Greek). Μεγασ Συναξαριστησ. Synaxarion.gr. Retrieved 2011-10-07

- "Мученик Иоанн-Владимир, князь Сербский" (in Russian). Православный Календарь. Pravoslavie.Ru. Retrieved 2011-10-07

- "Canonization". Feasts & Saints. Orthodox Church in America. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07

- Milović & Mustafić 2001, pp. 56–57

- Elsie 1995, pp. 108–13

- Fine 1994, p. 372

- Novaković 1893, pp. 218–37

- Novaković 1893, pp. 238–84

- Drakopoulou 2006, pp. 136–41

- Maksimov 2009, ch. "Монастырь во имя святого мученика Иоанна-Владимира"

- Velimirović & Stefanović 2000, ch. "Предговор"

- "Kisha e Manastirit (e restauruar)". Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.; "Konakët e Manastirit (të rikonstruktuar)" (in Albanian). Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.

- Milosavljević 2009, para. 14

- Koti 2006, para. 1

- Velimirović & Stefanović 2000, ch. "Патерик манастира светог Јована Владимира код Елбасана"

- Averky 2000, ch. "Temple Feasts"

- Averky 2000, ch. "The Daily Cycle of Services"

- Koti 2006, para. 2

- Averky 2000, chs. "The Daily Vespers", "Small Compline", "Daily Matins", "The Hours and the Typica"

- Milosavljević 2009, para. 1

- "Procession through the streets of Bar in glory and honour of St. Jovan Vladimir". The Information Service of the Serbian Orthodox Church. 7 June 2010. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- Mustafić 2001, pp. 30–31

- Milović 2001, para. 1

- Milović & Mustafić 2001, pp. 57–59

- Mustafić 2001, para. 7–9

- Yastrebov 1879, pp. 163–64

- Rovinsky 1888, pp. 360–61

- Jovićević 1922, pp. 149–50

- "Serbian Orthodox Church" Митрополит Амфилохије освештао Цркву Свете Тројице на Румији (in Serbian). The Information Service of the Serbian Orthodox Church. 1 August 2005. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- Dukić 2005, para. 1

- Kačić Miošić 1839, pp. 38–39

- Nicodemus 1868, pp. 165–66

- Yanich & Hankey 1921, ch. "The Life of Saint John Vladimir, Serbian Prince"

- Cosmas 1858, pp. 12–13

- Milosavljević 2009, sec. "Житије"

- Stojčević 1986, p. 395

- Popruzhenko 1928, pp. XII, XXXVIII, 77

- Paisius 1914, p. XI.

- Paisius 1914, pp. 59, 64, 75.

- Rousseva 2005–2006, pp. 167, 174, 178, 188

- Mirković & Zdravković 1952, pp. 16, 37

- Mirković & Zdravković 1952, pp. 65–68

- Cosmas 1858, n. pag.

- Velimirović & Stefanović 2000, ch. "Народна казивања о Краљу Владимиру"

- Kitevski 2011, para. 4–6

References

Printed sources

- Cosmas (1858) [1690]. Written at Elbasan, present-day Albania. Ακολουθια του αγιου ενδοξου βασιλεως, και μεγαλομαρτυρος Ιωαννου του Βλαδιμηρου και θαυματουργου (in Greek). Venice: Saint George Greek Press.

- Drakopoulou, Eugenia (2006). Tourta, Anastasia (ed.). Icons from the Orthodox Communities of Albania: Collection of the National Museum of Medieval Art, Korcë. Thessaloniki: European Centre for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Monuments. ISBN 960-89061-1-3.

- Elsie, Robert (1995). "The Elbasan Gospel Manuscript ("Anonimi i Elbasanit"), 1761, and the Struggle for an Original Albanian Alphabet" (PDF). Südost-Forschungen. Regensburg, Germany: Südost-Institut. 54. ISSN 0081-9077.

- Farlati, Daniele (1817). Illyricum Sacrum (in Latin). Vol. 7. Venice: Apud Sebastianum Coleti.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Jireček, Konstantin Josef (1911). Geschichte der Serben (in German). Vol. 1. Gotha, Germany: Friedriech Andreas Perthes A.-G.

- Jovićević, Andrija (1922). Црногорско Приморје и Крајина. Српски етнографски зборник (in Serbian). Belgrade: Serbian Royal Academy. 23.

- Kačić Miošić, Andrija (1839) [1756]. Razgovor ugodni naroda slovinskoga (in Croatian). Dubrovnik: Petar Fran Martecchini.

- Milović, Željko; Mustafić, Suljo (2001). Knjiga o Baru (in Serbian). Bar, Montenegro: Informativni centar Bar.

- Mirković, Lazar; Zdravković, Ivan (1952). Манастир Бођани (in Serbian). Belgrade: Naučna knjiga.

- Nicodemus the Hagiorite (1868) [1819]. Written at Mount Athos. Συναξαριστης των δωδεκα μηνων του ενιαυτου (in Greek). Vol. 2. Athens: The Press of Philadelpheus Nikolaides.

- Novaković, Stojan (1893). Први основи словенске књижевности међу балканским Словенима: Легенда о Владимиру и Косари (in Serbian). Belgrade: Serbian Royal Academy.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-8135-0599-2.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1998). Историја Византије (in Serbian). Belgrade: Narodna knjiga.

- Stojčević, ed. (1986). Србљак (in Church Slavic). Belgrade: The Holy Synod of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Popruzhenko, Mikhail Georgievich, ed. (1928) [1211]. Синодикъ царя Борила (in Church Slavic and Russian). Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- Rousseva, Ralitsa (2005–2006). "Iconographic Characteristics of the Churches in Moschopolis and Vithkuqi (Albania)" (PDF). Makedonika. Thessaloniki: Society for Macedonian Studies. 35. ISSN 0076-289X.

- Rovinsky, Pavel Apollonovich (1888). Черногорія въ ея прошломъ и настоящемъ (in Russian). Vol. 1. Saint Petersburg: The Press of the Imperial Academy of Sciences.

- Skylitzes, John; Cedrenus, George (1839) [11th century]. Bekker, Imannuel (ed.). Georgius Cedrenus Ioannis Scylitze Ope (in Greek and Latin). Vol. 2. Bonn, Germany: Impensis ed. Weberi.

- Stephenson, Paul (2005) [2000]. Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-03402-2.

- Yanich, Voyeslav; Hankey, Cyril Patrick, eds. (1921). Lives of the Serbian Saints. Translations of Christian Literature, Series VII. London: The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Yastrebov, Ivan Stepanovich (1879). Податци за историју Српске цркве: из путничког записника (in Serbian). Belgrade: The State Press.

- Živković, Tibor (2002). Поход бугарског цара Самуила на Далмацију. Istorijski časopis (in Serbian). Belgrade: The Institute of History of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 49. ISSN 0350-0802.

- Živković, Tibor (2006). Портрети српских владара (IX-XII век) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Zavod za udžbenike. ISBN 86-17-13754-1.

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa. ISBN 9788675585732.

- Кунчер, Драгана (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 1. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Живковић, Тибор (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 2. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

Online sources

- Averky (2000) [1951]. Laurus (ed.). Liturgics. Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Orthodox School. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

- Dukić, Davor (2005). "Kačić Miošić, Andrija". Hrvatski biografski leksikon (in Croatian). The Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.

- Filipović, Stefan Trajković, ""Oh, Vladimir, King of Dioclea, Hard Headed, Heart Full of Pride!" Isaiah Berlin and Nineteenth Century Interpretations of the Live of Saint Vladimir of Dioclea", Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology, Filozofski fakultet, 9 (3)

- Kitevski, Marko (2011). "Свети великомаченик кнез Јован Владимир". Култура и туризам (in Macedonian). mn.mk. Archived from the original on 2015-02-24.

- Koti, Isidor (2006). Celebration of Saint John Vladimir in Elbasan. Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- Maksimov, Yuri (2009). Монастыри Албанской Православной Церкви. Поместные Церкви (in Russian). Pravoslavie.Ru. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.

- Milosavljević, Čedomir (2009). Св. Јован Владимир (in Serbian). Pravoslavna Crkvena Opština Barska. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.

- Milović, Željko (2001). Skulptura, bliska svima (in Serbian). BARinfo. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- Mustafić, Suljo (2001). Krst se čuva u Mikuliće, niđe drugo (in Serbian). BARinfo. Archived from the original on 2010-05-24.

- Paisius (1914) [1762], Yordan Ivanov (ed.), Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya (PDF) (in Bulgarian)

- Rudger (2010) [ca. 1300]. Stephenson, Paul (ed.). "Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja (Ljetopis Popa Dukljanina), Chapter 36". Translated Excerpts from Byzantine Sources. Paul Stephenson. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14.

- Velimirović, Bishop Nikolaj; Stefanović, Zoran, eds. (2000) [1925]. Читанка о Светоме краљу Јовану Владимиру (in Serbian). Project Rastko. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10.

External links

Videos:

- Procession in Bar, Montenegro, on the Feast of Saint Jovan Vladimir, led by the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral (2011)

- Modern Albanian song about Saint Jovan Vladimir, performed at the monastery near Elbasan on the saint's feast day (2010)

- Opening of the reliquary containing the saint's relics, during the celebration of his feast day at the monastery near Elbasan (2011)

- Ascent to the Church of the Holy Trinity at the summit of Mount Rumija, for the monthly service held in the church