Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (German: [kataˈʁiːnaː fɔn ˈboːʁaː]; 29 January 1499 – 20 December 1552), after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin" ("the Lutheress"),[1] was the wife of Martin Luther, German reformer and a seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation. Beyond what is found in the writings of Luther and some of his contemporaries, little is known about her. Despite this, Katharina is often considered an important participant of the Reformation because of her role in helping to set precedents for Protestant family life and clergy marriages.[2]

Katharina von Bora | |

|---|---|

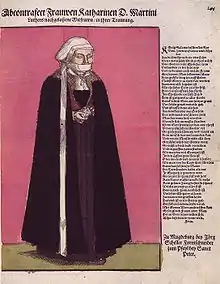

Portrait of Catherine von Bora by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1526 oil on panel | |

| Born | 29 January 1499 Lippendorf, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 20 December 1552 (aged 53) Torgau, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

Origin and family background

Katharina von Bora was the daughter to a family of Saxon lesser nobility.[3] According to common belief, she was born on 29 January 1499, in Lippendorf, but there is no evidence of this date from contemporary documents. Due to the various lineages within the family and the uncertainty about Katharina's birth name, there were and are diverging theories about her place of birth.[4][5]

Recently a different perspective has been proposed: that she was born in Hirschfeld and that her parents are supposed to have been a Hans von Bora zu Hirschfeld and his wife Anna von Haugwitz.[6] Neither can be proven. It is also possible that Katharina was the daughter of a Jan von Bora auf Lippendorf and his wife Margarete, whose family name has not been established. Both were specifically mentioned only in the year 1505.[7]

Life as a nun

It is certain that her father sent the five-year-old Katharina to the Benedictine cloister in Brehna in 1504 for education. This is documented in a letter from Laurentius Zoch to Martin Luther, written on 30 October 1531. This letter is the only evidence of Katharina von Bora's spending time in the monastery.[8] At the age of nine she moved to the Cistercian monastery of Marienthron (Mary's Throne) in Nimbschen, near Grimma, where her maternal aunt was already a member of the community.[9] Katharina is well documented at this monastery in a provision list of 1509/10.[10]

After several years of religious life, Katharina became interested in the growing reform movement and grew dissatisfied with her life in the convent. Conspiring with several other nuns to flee in secrecy, she contacted Luther and begged for his assistance.[11] On Easter Eve, 4 April 1523, Luther sent Leonhard Köppe, a city councilman of Torgau and a merchant who regularly delivered herring to the convent. The nuns escaped by hiding in Köppe's covered wagon among the fish barrels, and fled to Wittenberg. A local student wrote to a friend: "A wagon load of vestal virgins has just come to town, all more eager for marriage than for life. God grant them husbands lest worse befall."[12]

Luther at first asked the parents and relations of the refugee nuns to admit them again into their houses, but they declined to receive them, possibly because this would make them accomplices to a crime under canon law.[13] Within two years, Luther was able to arrange homes, marriages, or employment for all of the escaped nuns except Katharina. She was first housed with the family of Philipp Reichenbach, the city clerk of Wittenberg. Later she went to the home of Lucas Cranach the Elder and his wife, Barbara.

Katharina had a number of suitors, including the Wittenberg University alumnus Hieronymus Baumgartner of Nuremberg, and a pastor, Kaspar Glatz of Orlamünde. None of the proposed matches resulted in marriage. She told Luther's friend and fellow reformer, Nikolaus von Amsdorf, that she would be willing to marry only Luther or von Amsdorf himself.[14]

Marriage to Luther

Martin Luther, and many of his friends as well, were at first unsure of whether he should even be married. Philipp Melanchthon thought that Luther's marriage would hurt the Reformation because of potential scandal. Luther eventually came to the conclusion that "his marriage would please his father, rile the pope, cause the angels to laugh, and the devils to weep."[14] Luther married Katharina on 13 June 1525, before witnesses including Justus Jonas, Johannes Bugenhagen, and Barbara and Lucas Cranach the Elder.[15]

They held a wedding breakfast the next morning with a small company. Two weeks later, on 27 June, they held a more formal public ceremony, presided over by Bugenhagen.[16] Von Bora was 26 years old, Luther 41. The couple took up residence in the "Black Cloister" (Augusteum), the former dormitory and educational institution for Augustinian friars studying in Wittenberg, given as a wedding gift by the reform-minded John, Elector of Saxony, who was the brother of Luther's protector Frederick III, Elector of Saxony.[17]

Katharina immediately took on the task of administering and managing the monastery's vast holdings, breeding and selling cattle and running a brewery to provide for their family, the steady stream of students who boarded with them, and visitors seeking audiences with her husband. In times of widespread illness, she operated a hospital on site, ministering to the sick alongside other nurses. Luther called her the "boss of Zulsdorf", after the name of the farm they owned, and the "morning star of Wittenberg" for her habit of rising at 4 a.m. to take care of her various responsibilities.[18]

The marriage of von Bora to Luther was extremely important to the development of the Protestant Church, specifically in regard to its stance on marriage and the roles each spouse should concern themselves with. "Although Luther was by no means the first cleric of his time to marry, his prominence, his espousal of clerical marriage, and his prolific output of printed anti-Catholic propaganda made his marriage a natural target."[19] The way Luther described Katie's actions and the names he gives her like "My Lord Katie" shows us that he really did feel strongly that she exhibited a great amount of control over her own life and decisions. It could even reasonably be argued that she maintained some influence in the actions of Martin Luther himself since he says explicitly, "You convince me of whatever you please. You have complete control. I concede to you the control of the household, providing my rights are preserved. Female government has never done any good".[20] Luther also makes the statement "If I can endure conflict with the devil, sin, and a bad conscience, then I can put up with the irritations of Katy von Bora."[21]

In addition to her busy life tending to the lands and grounds of the monastery, Katharina bore six children: Hans (1526–1575), Elizabeth (1527–1528) who died at eight months, Magdalena (1529–1542) who died at thirteen years, Martin (1531–1565), Paul (1533–1593), and Margarete (1534–1570); in addition she suffered a miscarriage on 1 November 1539. The Luthers also raised four orphan children, including Katharina's nephew, Fabian.[22]

Anecdotal evidence indicates that von Bora's role as the wife of a critical member of the Reformation paralleled the marital teachings of Luther and the movement. Katharina depended on Luther such as for his incomes before the estate's profits increased, thanks to her. She respected him as a higher vessel and called him formally "Sir Doctor" throughout her life. He reciprocated such respect by occasionally consulting her on church matters.[23] She assisted him with running the estate duties as he could not complete both these and those to the church and university. Katharina also directed the renovations done to accommodate the size of their operations.[24]

After Luther's death

When Martin Luther died in 1546, Katharina was left in difficult financial straits without Luther's salary as professor and pastor, even though she owned land, properties, and the Black Cloister. She was counselled by Martin Luther to move out of the old abbey and sell it after his death, and move into much more modest quarters with the children who remained at home, but she refused.[25] Luther had named her his sole heir in his last will. His will could not be executed because it did not conform with Saxon law.[26]

Almost immediately after, Katharina had to leave the Black Cloister (now called Lutherhaus) by herself, at the outbreak of the Schmalkaldic War, fleeing to Magdeburg. After she returned, the approaching war forced another flight in 1547, this time to Braunschweig. In July 1547, at the close of the war, she was able to return to Wittenberg.

After the war, the buildings and lands of the monastery had been torn apart and laid waste, and cattle and other farm animals had been stolen or killed. If she had sold the land and the buildings, she could have had a good financial situation. Financially, they could not remain there. Katharina was able to support herself thanks to the generosity of John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony and the princes of Anhalt.[27]

She remained in Wittenberg in poverty until 1552, when an outbreak of the Black Plague and a harvest failure forced her to leave the city once again. She fled to Torgau where she was thrown from her cart into a watery ditch near the city gates. For three months she went in and out of consciousness, before dying in Torgau on 20 December 1552, at the age of 53. She was buried at Torgau's Saint Mary's Church, far from her husband's grave in Wittenberg. She is reported to have said on her deathbed, "I will stick to Christ as a burr to cloth."[28]

By the time of Katharina's death, the surviving Luther children were adults. After Katharina's death, the Black Cloister was sold back to the university in 1564 by his heirs.

Margareta Luther, born in Wittenberg on 27 December 1534, married into a noble, wealthy Prussian family, to Georg von Kunheim (Wehlau, 1 July 1523 – Mühlhausen (now Gvardeyskoye, Kaliningrad Oblast), 18 October 1611, the son of Georg von Kunheim (1480–1543) and wife Margarethe, Truchsessin von Wetzhausen (1490–1527)) but died in Mühlhausen in 1570 at the age of thirty-six.[29] Her descendants have continued to modern times, including German President Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934) and the Counts zu Eulenburg and Princes zu Eulenburg and Hertefeld.[30][31]

Commemoration

Katharina von Bora is commemorated on 20 December in the Calendar of Saints of some Lutheran Churches in the United States.[32] In 2022, she was officially added to the Episcopal Church liturgical calendar with a feast day on 20 December.[33]

In addition to a statue in Wittenberg and several biographies, an opera of her life now keeps her memory alive.

References

Citations

- Rixner, T.A. (1 January 1830). "Handwörterbuch der deuschen Sprache" Vol. 1 A-K, page 290 (in German). p. 290.

- "How a Runaway Nun Helped an Outlaw Monk Change the World". National Geographic Society. 20 October 2017.

- Fischer/v.Stutterheim in: AfF (2005) pp. 242ff; Wagner in Genealogie (2005) pp. 673ff, Genealogie (2006) pp. 30ff; Wagner in FFM (2006), pp. 342ff

- D. Albrecht Thoma, Katharina von Bora: Geschichtliches Lebensbild (1900)

- Fischer/v.Stutterheim, 'Zur Herkunft der Katharina v. Bora, Ehefrau Martin Luther's', in AfF (2005), pp. 242ff; Jürgen Wagner, 'Zur mutmaßlichen Herkunft der Catherina v. Bora' in Genealogie (2005), pp. 730ff, Genealogie (2006), pp. 30ff; Jürgen Wagner in FFM (2006), pp. 342ff

- Georg von Hirschfeld, 'Die Beziehungen Luthers und seiner Gemahlin, Katharina von Bora, zur Familie von Hirschfeld' in Beiträge zur sächssischen Kirchengeschichte (1883), pp. 83ff; Wolfgang Liebehenschel, Der langsame Aufstieg des Morgensterns von Wittenberg (Oschersleben, 1999), p. 79

- Jürgen Wagner, 'Zur Geschichte der Familie v. Bora und einiger Güter in den sächsischen Ämtern Borna und Pegau: Wer waren Martin Luther's Schwiegereltern?' in Genealogie (2010), p. 300

- D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Briefwechsel. 6. Band. Weimar 1935 Nr. 1879 s. 219

- "500th Anniversary of Katharina von Bora". Augustana. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- CDS Codex Diplomaticus Saxoniae Regiae II 15 Nr. 455

- "Katharina von Bora Luther – Lutheran Reformation". Lutheran Reformation. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Bainton, Here I Stand, p. 223.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Germany, TourComm. "Katharina von Bora (1499–1552)" (in German).

- Rix, Herbert David (1983). Martin Luther: the man and the image. Ardent Media. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8290-0554-7. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- D. Martin Luthers Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Tischreden. 6 vols. Weimar: Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1912–21

- "How a Runaway Nun Helped an Outlaw Monk Change the World". 20 October 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Smith, Jeanette. "Katharina Von Bora Through Five Centuries: A Historiography". The Sixteenth Century Journal, 30.3 (1999): 745.

- Lehman 1967, p. 174.

- Lehman 1967, p. 34.

- Peterson, Susan Lynn, Luther's Later Years (1538–1546).

- Karant-Nunn, Susan C., and Merry E. Wiesner. Luther On Women: A Sourcebook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 3 December 2014.

- Treu, Martin. "Katharina von Bora, the Woman at Luther's Side". Lutheran Quarterly; 13.2 (1999): 156–178. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 3 December 2014.

- Johan Theophil Bring, The Wife and Home of Luther. 1917, Stockholm

- tough and valiant: luthers herr katie

- Schymonski, Wolfgang. "Katharina von Bora, die Lutherin". www.lutherin.de. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Fisher, Mary Pat (2007). Women in Religion. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 209. ISBN 9780321194817.

- "Margaretha von Kunheim". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Hindenburg, Marshal von (1921). Out of my life. 1. Translated by F. A. Holt. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 1–19.

- Maseko, Achim (2008). Church Schism & Corruption. Durban, South Africa: Lulu.com. p. 284. ISBN 9781409221869.

- Lutheran Service Book, xiii. Concordia Publishing House, 2006.

- "General Convention Virtual Binder". www.vbinder.net. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

Works cited

- Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, New York: Penguin, 1995, c1950. 336 p. ISBN 0-452-01146-9.

- Lehman (1967). Luther's Works. Vol. 54. edited and translated by Theodore G. Tappert. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Further reading

- Roland H. Bainton, Women of the Reformation in Germany and Italy, Augsburg Fortress Publishers (Hardcover), 1971. ISBN 0-8066-1116-2. Academic Renewal Press (Paperback), 2001. 279 p. ISBN 0-7880-9909-4.

- Hans J. Hillerbrand, ed. The Reformation: A Narrative History Related by Contemporary Observers and Participants, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1979.

- E. Jane Mall, Kitty, My Rib, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959. ISBN 0-570-03113-3.

- Luther's Works, 55 volumes of lectures, commentaries and sermons, translated into English and published by Concordia Publishing House and Fortress Press, 1957; released on CD-ROM, 2001.

- Heiko A. Oberman, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, trans. Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart (New York: Image, 1992).

- Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation, 1521–1532, trans. James L. Schaaf (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990); esp. chapter 4, "Marriage, Home, and Family (1525–30)."

- Yvonne Davy, Frau Luther.

- Karant-Nunn, Susan C., and Merry E. Wiesner. Luther On Women: A Sourcebook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 3 December 2014.

External links

- A website devoted to Katharina von Bora (in German)

- The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod (USA) Concordia Historical Institute website on Katherine von Bora

- John Gottlieb Morris,[1] 1803–1895 Catherine de Bora: Or Social and Domestic Scenes in the Home of Luther 1856

- Hermann Nietschmann 1840–1929 Katharine von Bora, Dr. Martin Luther's wife. A picture from life (1890)

- *Chronological catalog of Luther's life events, letters, and works with citations, 478 pages, 5.45 MB LettersLuther4.doc

- A Modern skit about Martin and Katharina YouTube