Lebensraum

Lebensraum (German pronunciation: [ˈleːbənsˌʁaʊm] (![]() listen), 'living space') is a German concept which consists of policies and practices of settler colonialism which proliferated in Germany from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901,[2] Lebensraum became a geopolitical goal of Imperial Germany in World War I (1914–1918) originally, as the core element of the Septemberprogramm of territorial expansion.[3] The most extreme form of this ideology was supported by the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and Nazi Germany. Lebensraum was one of the leading motivations Nazi Germany had in initiating World War II, and it would continue this policy until the end of World War II.[4]

listen), 'living space') is a German concept which consists of policies and practices of settler colonialism which proliferated in Germany from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901,[2] Lebensraum became a geopolitical goal of Imperial Germany in World War I (1914–1918) originally, as the core element of the Septemberprogramm of territorial expansion.[3] The most extreme form of this ideology was supported by the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and Nazi Germany. Lebensraum was one of the leading motivations Nazi Germany had in initiating World War II, and it would continue this policy until the end of World War II.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

|

Following Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Lebensraum became an ideological principle of Nazism and provided justification for the German territorial expansion into Central and Eastern Europe.[5] The Nazi Generalplan Ost policy ('Master Plan for the East') was based on its tenets. It stipulated that Germany required a Lebensraum necessary for its survival and that most of the indigenous populations of Central and Eastern Europe would have to be removed permanently (either through mass deportation to Siberia, extermination, or enslavement) including Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, Czech and other Slavic nations considered non-Aryan. The Nazi government aimed at repopulating these lands with Germanic colonists in the name of Lebensraum during and following World War II.[6][7][8][9] Entire indigenous populations were decimated by starvation, allowing for their own agricultural surplus to feed Germany.[6]

Hitler's strategic program for world domination was based on the belief in the power of Lebensraum, especially when pursued by a racially superior society.[7] People deemed to be part of non-Aryan races, within the territory of Lebensraum expansion, were subjected to expulsion or destruction.[7] The eugenics of Lebensraum assumed it to be the right of the German Aryan master race (Herrenvolk) to remove the indigenous people in the name of their own living space. They took inspiration for this concept from outside Germany.[7] Nazi officials and Hitler in particular took a particular interest in Manifest Destiny, and attempted to replicate it in occupied Europe.[9] Nazi Germany also supported other Axis Powers' expansionist ideologies such as Fascist Italy's spazio vitale and Imperial Japan's Hakkō ichiu.[10]

Origins

In the 19th century, the term Lebensraum was used by the German geographer and biologist Oscar Peschel in his 1860 review of Charles Darwin's Origins of Species (1859).[11] In 1897, the geographer and ethnographer Friedrich Ratzel in his book Politische Geographie applied the word Lebensraum ("living space")[2] to describe physical geography as a factor that influences human activities in developing into a society.[12] In 1901, Ratzel extended his thesis in his essay titled "Lebensraum".[13]

During the First World War, the Allied naval blockade of the Central Powers caused food shortages in Germany and resources from Germany colonies in Africa were unable to slip past the blockade; this caused support to rise during the war for a Lebensraum that would expand Germany eastward into Russia to gain control of their resources to prevent such a situation from occurring in the future.[14] In the period between the First and the Second World Wars, German nationalists adopted the term Lebensraum in their political demands for the re-establishment of the German colonial empire, which had been dismembered by the Allies at Versailles.[15][16] Ratzel said that the development of a people into a society was primarily influenced by their geographic situation (habitat) and that a society that successfully adapted to one geographic territory would naturally and logically expand the boundaries of their nation into another territory.[13] Yet, to resolve German overpopulation, Ratzel said that Imperial Germany (1871–1918) required overseas colonies to which surplus Germans ought to emigrate.[17]

Geopolitics

Friedrich Ratzel's metaphoric concept of society as an organism—which grows and shrinks in logical relation to its Lebensraum (habitat)—proved especially influential upon the Swedish political scientist and conservative politician Johan Rudolf Kjellén (1864–1922) who interpreted that biological metaphor as a geopolitical natural-law.[18] In the political monograph Schweden (1917; Sweden), Kjellén coined the terms geopolitik (the conditions and problems of a state that arise from its geographic territory), œcopolitik (the economic factors that affect the power of the state), and demopolitik (the social problems that arise from the racial composition of the state) to explain the political particulars to be considered for the successful administration and governing of a state. Moreover, he had a great intellectual influence upon the politics of Imperial Germany, especially with Staten som livsform (1916; The State as a Life-form), an earlier political-science book read by the society of Imperial Germany, for whom the concept of geopolitik acquired an ideological definition unlike the original, human-geography definition.[19]

Kjellén's geopolitical interpretation of the Lebensraum concept was adopted, expanded, and adapted to the politics of Germany by publicists of imperialism such as the militarist General Friedrich von Bernhardi (1849–1930) and the political geographer and proponent of geopolitics Karl Haushofer (1869–1946). In Deutschland und der Nächste Krieg (1911; Germany and the Next War), General von Bernhardi developed Friedrich Ratzel's Lebensraum concept as a racial struggle for living space, explicitly identified Eastern Europe as the source of a new, national habitat for the German people, and said that the next war would be expressly for acquiring Lebensraum—all in fulfillment of the "biological necessity" to protect German racial supremacy. Vanquishing the Slavic and the Latin races was deemed necessary because "without war, inferior or decaying races would easily choke the growth of healthy, budding elements" of the German race—thus, the war for Lebensraum was a necessary means of defending Germany against cultural stagnation and the racial degeneracy of miscegenation.[20]

Racial ideology

In the national politics of Weimar Germany, the geopolitical usage of Lebensraum is credited to Karl Ernst Haushofer and his Institute of Geopolitics, in Munich, especially the ultra-nationalist interpretation to avenge military defeat in the First World War (1914–18), and reverse the dictates of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), which reduced Germany geographically, economically, and militarily. The politician Adolf Hitler said that the Nazi geopolitics of "inevitable expansion" would reverse overpopulation, provide natural resources, and uphold German national honor.[21] In Mein Kampf (1925; My Struggle), Hitler presented his conception of Lebensraum as the philosophic basis for the Greater Germanic Reich that was destined to colonize Eastern Europe—especially Ukraine in the Soviet Union—and so resolve the problems of overpopulation, and that the European states had to accede to his geopolitical demands.[22][23]

The Nazi usages of the term Lebensraum were explicitly racial, to justify the mystical right of the racially superior Germanic peoples (Herrenvolk) to fulfill their cultural destiny at the expense of racially inferior peoples (Untermenschen), such as the Slavs of Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and the other non–Germanic peoples of "the East".[3] Based upon Johan Rudolf Kjellén's geopolitical interpretation of Friedrich Ratzel's human-geography term, the Nazi régime (1933–45) established Lebensraum as the racist rationale of the foreign policy by which they began the Second World War, on 1 September 1939, in an effort to realise the Greater Germanic Reich at the expense of the societies of Eastern Europe.[19]

First World War nationalist premise

In September 1914, when the German victory in the First World War appeared feasible, the government of Imperial Germany introduced the Septemberprogramm as an official war aim (Kriegsziel), which was secretly endorsed by Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg (1909–17), whereby, upon achieving battlefield victory, Germany would annex territories from western Poland to form the Polish Border Strip (Polnischer Grenzstreifen, c. 30,000 km2). Lebensraum would be realised by way of ethnic cleansing, the forcible removal of the native Slavic and Jewish populations, and the subsequent repopulation of the border strip with ethnic-German colonists; likewise, the colonisations of Lithuania and Ukraine; yet military over-extension lost the war for Imperial Germany, and the Septemberprogramm went unrealised.[24]

In April 1915, Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg authorised the Polish Border Strip plans in order to take advantage of the extensive territories in Eastern Europe that Germany had conquered and held since early in the war.[25] The decisive campaigns of Imperial Germany almost realised Lebensraum in the East, especially when Bolshevik Russia unilaterally withdrew as a combatant in the "Great War" among the European great powers—the Triple Entente (the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom) and the Central Powers (the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria).[26]

In March 1918, in an effort to reform and modernise the Russian Empire (1721–1917) into a soviet republic, the Bolshevik government agreed to the strategically onerous territorial cessions stipulated in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918), and Russia yielded to Germany much of the arable land of European Russia, the Baltic governorates, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Caucasus region.[27] Despite such an extensive geopolitical victory, tactical defeat in the Western Front, strategic over-extension, and factional division in government compelled Imperial Germany to abandon the eastern European Lebensraum gained with the Brest-Litovsk Treaty (33 per cent of arable land, 30 per cent of industry, and 90 per cent of the coal mines of Russia) in favour of the peace-terms of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), and yielded those Russian lands to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine.

As a casus belli for the conquest and colonisation of Polish territories as living-space and defensive-border for Imperial Germany, the Septemberprogramm derived from a foreign policy initially proposed by General Erich Ludendorff in 1914.[25] Twenty-five years later, Nazi foreign policy resumed the cultural goal of the pursuit and realisation of German-living-space at the expense of non-German peoples in Eastern Europe with the September Campaign (1 September – 6 October 1939) that began the Second World War in Europe.[28] In Germany and the Two World Wars (1967), the German historian Andreas Hillgruber said that the territorial gains of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) were the imperial prototype for Adolf Hitler's Greater German Empire in Eastern Europe:

At the moment of the November 1918 ceasefire in the West, newspaper maps of the military situation showed German troops in Finland, holding a line from the Finnish fjords near Narva, down through Pskov–Orsha–Mogilev and the area south of Kursk, to the Don east of Rostov. Germany had thus secured Ukraine. The Russian recognition of Ukraine's separation, exacted at Brest–Litovsk, represented the key element in German efforts to keep Russia perpetually subservient. In addition, German troops held the Crimea, and were stationed, in smaller numbers, in Transcaucasia. Even the unoccupied "rump" Russia appeared—with the conclusion of the German–Soviet Supplementary Treaty, on 28 August 1918—to be in firm, though indirect, dependency on the Reich. Thus, Hitler's long-range aim, fixed in the 1920s, of erecting a German Eastern Imperium on the ruins of the Soviet Union was not simply a vision emanating from an abstract wish. In the Eastern sphere, established in 1918, this goal had a concrete point of departure. The German Eastern Imperium had already been—if only for a short time—a reality. —Andreas Hillgruber. Germany and the Two World Wars[29]

The Septemberprogramm (1914) documents "Lebensraum in the East" as philosophically integral to Germanic culture throughout the history of Germany; and that Lebensraum is not a racialist philosophy particular to the 20th century.[30] As military strategy, the Septemberprogramm came to nought for being infeasible—too few soldiers to realise the plans—during a two-front war; politically, the Programm allowed the Imperial Government to learn the opinions of the nationalist, economic, and military élites of the German ruling class who finance and facilitate geopolitics.[31] Nationally, the annexation and ethnic cleansing of Poland for German Lebensraum was an official and a popular subject of "nationalism-as-national-security" endorsed by German society, including the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP).[32] In The Origins of the Second World War the British historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote.

It is equally obvious that Lebensraum always appeared as one element in these blueprints. This was not an original idea of Hitler's. It was commonplace at the time. Volk ohne Raum (People Without Space), for instance, by Hans Grimm sold much better than Mein Kampf when it was published in 1925. For that matter, plans for acquiring new territory were much aired in Germany during the First World War. It used to be thought that these were the plans of a few crack-pot theorisers or of extremist organisations. Now we know better. In 1961, a German professor Fritz Fischer reported the results of his investigations into German war aims. These were indeed a "blueprint for aggression", or, as the professor called them, "a grasp at world power": Belgium under German control, the French iron-fields annexed to Germany, and, what is more, Poland and Ukraine to be cleared of their inhabitants and resettled with Germans. These plans were not merely the work of the German General Staff. They were endorsed by the German Foreign Office and by the "Good German", Bethmann–Hollweg. —Alan J. Taylor, The Origins of the Second World War[33]

Interwar propaganda

In the national politics of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), the German Eugenicists took up the nationalist, political slogan of Volk ohne Raum, and matched it with the racial slogan Volk ohne Jugend (a People without Youth), a cultural proposition that ignored the declining German birth-rate (since the 1880s) and contradicted the popular belief that the "German race" was a vigorous and growing people. Despite each slogan (political and racial) being contradicted by the reality of such demographic facts, the nationalists' demands for Lebensraum proved to be ideologically valid politics in Weimar Germany.[34][35]

In the lead-up to Anschluss (1938) and the invasion of Poland (1939) the propaganda of Nazi Party in Germany used popular feelings of wounded national identity aroused in the aftermath of the First World War to promote policies of Lebensraum. Studies of the homeland focused on the lost colonies after the establishment of the Second Polish Republic which was ratified by the Treaty of Versailles (Volk ohne Raum), as well as the "eternal Jewish threat" (Der ewige Jude, 1937). Emphasis was put on the need for rearmament and the pseudoscience of superior races in the pursuit of "blood and soil".[36]

In the twenty-one year inter-war period, between the First (1914–18) and the Second (1939–45) world wars, Lebensraum for Germany was the principal tenet of the extremist nationalism that characterised the party politics in Germany. The Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, demanded not only the geographic reversion of Germany's post-war borders (to recuperate territory lost per the Treaty of Versailles), but demanded the German conquest and colonisation of Eastern Europe (whether or not those lands were German before 1918).[37] To that end, Hitler said that flouting the Treaty of Versailles was required for Germany to obtain needed Lebensraum in Eastern Europe.[38] During the 1920s, as a member of the Artaman League, an anti-Slav, anti-urban, and anti-Semitic organisation of blood-and-soil ideology, Heinrich Himmler developed völkisch ideas that advocated Lebensraum, for the realisation of which he said that the:

Increase [of] our peasant population is the only effective defense against the influx of the Slav working-class masses from the East. As six hundred years ago, the German peasant's destiny must be to preserve and increase the German people's patrimony in their holy mother earth battle against the Slav race.[39]

Lebensraum as theory in Hitlerism

In Mein Kampf (1925), Hitler dedicated a full chapter titled "Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy", outlining the need for the new 'living space' for Germany. He claimed that achieving Lebensraum required political will, and that the Nazi movement ought to strive to expand population area for the German people, and acquire new sources of food as well.[40] Lebensraum became the principal foreign-policy goal of the Nazi Party and the government of Nazi Germany (1933–45). Hitler rejected the restoration of the pre-war borders of Germany as an inadequate half-measure towards reducing purported national overpopulation.[41] From that perspective, he opined that the nature of national borders is always unfinished and momentary, and that their redrawing must continue as Germany's political goal.[42] Hence, Hitler identified the geopolitics of Lebensraum as the ultimate political will of his Party:

And so, we National Socialists consciously draw a line beneath the foreign policy tendency of our pre–War period. We take up where we broke off six hundred years ago. We stop the endless German movement to the south and west, and turn our gaze toward the land in the East. At long last, we break off the colonial and commercial policy of the pre–War period and shift to the soil policy of the future.[43]

The ideologies found at the root of Hitler's implementation of Lebensraum modeled that of German colonialism of the New Imperialism period as well as the American ideology of Manifest destiny. Hitler had great admiration for the United States' territorial expansion and was fascinated by the genocide of Native Americans that took place during the United States' westward expansion and used this in part for justification of German expansion. He believed that in order to transform the German nation into a world superpower, Germany had to expand their geopolitical presence and act only in the interest of the German people. Hitler had also viewed with dismay the German reliance on food imports by sea during the First World War, believing it to be a contributing factor to Germany's defeat in the war. He believed that only through Lebensraum could Germany shift " its dependence for food... to its own imperial hinterland".[44]

"There is only one task: Germanization through the introduction of Germans [to the area] and to treat the original inhabitants like Indians. … I intend to stay this course with ice-cold determination. I feel myself to be the executor of the will of History. What people think of me at present is all of no consequence. Never have I heard a German who has bread to eat express concern that the ground where the grain was grown had to be conquered by the sword. We eat Canadian wheat and never think of the Indians."[45]

Mein Kampf sequel, 1928

In the unpublished sequel to Mein Kampf, the Zweites Buch (1928, Second Book), Hitler further presents the ideology of Nazi Lebensraum, in accordance to the then-future foreign policy of the Nazi Party. To further German population growth, Hitler rejected the ideas of birth control and emigration, arguing that such practices weakened the people and culture of Germany, and that military conquest was the only means for obtaining Lebensraum:

The National Socialist Movement, on the contrary, will always let its foreign policy be determined by the necessity to secure the space necessary to the life of our Folk. It knows no Germanising or Teutonising, as in the case of the national bourgeoisie, but only the spread of its own Folk. It will never see in the subjugated, so called Germanised, Czechs or Poles a national, let alone Folkish, strengthening, but only the racial weakening of our Folk.[46]

Therefore, the non-Germanic peoples of the annexed foreign territories would never be Germanised:

The völkisch State, conversely, must under no conditions annex Poles with the intention of wanting to make Germans out of them some day. On the contrary, it must muster the determination either to seal off these alien racial elements, so that the blood of its own Folk will not be corrupted again, or it must, without further ado, remove them and hand over the vacated territory to its own National Comrades.[47]

Foreign-policy prime directive

The conquest of living space for Germany was the foremost foreign-policy goal of the Nazis towards establishing the Greater Germanic Reich that was to last a thousand years.[48] On 3 February 1933, at his initial meeting with the generals and admirals of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler said that the conquest of Lebensraum in Eastern Europe, and its "ruthless Germanisation", were the ultimate geopolitical objectives of Reich foreign policy.[49][50] The USSR was the country to provide sufficient Lebensraum for the Germans, because it possessed much agricultural land, and was inhabited by Slavic Untermenschen ruled by Jewish Bolshevism.[51] The racism of Hitler's Lebensraum philosophy allowed only the Germanisation of the soil and the land, but not of the native peoples, who were to be destroyed, by slave labour and starvation.[52]

Ideological Motives

In the worldview of Adolf Hitler, the idea of restoring the 1914 borders of the German Reich (Imperial Germany, 1871–1918) was absurd, because those national borders did not provide sufficient Lebensraum for the German population; that only a foreign policy for the geopolitical conquest of the proper amount of Lebensraum would justify the necessary sacrifices entailed by war.[53] That history was dominated by a merciless struggle for survival among the different races of mankind; and that the races who possessed a great national territory were innately stronger than those races who possessed a small national territory—which the Germanic Aryan race can take by natural right.[54] Such official racist perspectives for the establishment of German Lebensraum allowed the Nazis to unilaterally launch a war of aggression (Blitzkrieg) against the countries of Eastern Europe, ideologically justified as historical recuperation of the Oium (lands) that the Slavs had conquered from the native Ostrogoths.[55] Although in the 1920s Hitler openly spoke about the need for living space, during his first years in power, he never publicly spoke about it. It was not until 1937 with the German rearmament program well under way that he began to publicly speak about the need for living space again.[56]

Lebensraum in practice: the Second World War

On 6 October 1939, Hitler told the Reichstag that after the fall of Poland the most important matter was "a new order of ethnographic relations, that is to say, resettlement of nationalities".[57] On 20 October 1939, Hitler told General Wilhelm Keitel that the war would be a difficult "racial struggle" and that the General Government was to "purify the Reich territory from Jews and Polacks, too."[58] Likewise, in October 1939, Nazi propaganda instructed Germans to view Poles, Jews, and Gypsies as Untermenschen.[59]

In 1941, in a speech to the Eastern Front Battle Group Nord, Himmler said that the war against the Soviet Union was a war of ideologies and races, between Nazism and Jewish Bolshevism and between the Germanic (Nordic) peoples and the Untermenschen peoples of the East.[60] Moreover, in one of the secret Posen speeches to the SS-Gruppenführer at Posen, Himmler said: "the mixed race of the Slavs is based on a sub-race with a few drops of our blood, the blood of a leading race; the Slav is unable to control himself and create order."[61] In that vein, Himmler published the pamphlet Der Untermensch, which featured photographs of ideal racial types, Aryans, contrasted with the barbarian races, descended from Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan, to the massacres committed in the Soviet Union dominated by Jewish Bolshevism.[62]

With the Polish decrees (8 March 1940), the Nazis ensured that the racial inferiority of the Poles was legally recognized in the German Reich, and regulated the working and living conditions of Polish laborers (Zivilarbeiter).[63] The Polish Decrees also established that any Pole "who has sexual relations with a German man or woman, or approaches them in any other improper manner, will be punished by death."[64] The Gestapo were vigilant of sexual relations between Germans and Poles, and pursued anyone suspected of race defilement (Rassenschande); likewise, there were proscriptions of sexual relations between Germans and other ethnic groups brought in from Eastern Europe.[65]

As official policy, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler said that no drop of German blood would be lost or left behind to mingle with any alien races;[66] and that the Germanisation of Eastern Europe would be complete when "in the East dwell only men with truly German [and] Germanic blood".[67] In the secret memorandum Reflections on the Treatment of Peoples of Alien Races in the East (25 May 1940) Himmler outlined the future of the Eastern European peoples; (i) division of native ethnic groups found in the new living-space; (ii) limited, formal education of four years of elementary school (to teach them only how to write their names and to count to five hundred), and (iii) obey the orders of Germans.[68] Nonetheless, despite Nazi Germany's official racism, the extermination of the native populations of the countries of Eastern Europe was not always necessary, because the Racial policy of Nazi Germany regarded some Eastern European peoples as being of Aryan-Nordic stock, especially the local leaders.[69] On March 4, 1941, Himmler introduced the German People's List (Deutsche Volksliste), the purpose of it being to segregate the inhabitants of German-occupied territories into categories of desirability according to criteria.[70] In the same memorandum, Himmler advocated the kidnapping of children who appeared to be Nordic because it would "remove the danger that this subhuman people (Untermenschenvolk) of the East through such children might acquire a leader class from such people of good blood, which would be dangerous for us because they would be our equals."[71][72] According to Himmler, the destruction of the Soviet Union would have led to the exploitation of millions of peoples as slave labor in the occupied territories and the eventual re-population of the areas with Germans.[73]

Classification under the laws in the annexed territories

The Deutsche Volksliste was split into four categories.[70] Men in the first two categories were required to enlist for compulsory military service.[70] Membership in the SS was reserved for men from Category I only:

| Classification [70] | Translation | Heritage | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volksdeutsche | Ethnically German | German | Persons of German descent who had engaged themselves in favour of the Reich before 1939 |

| Deutschstämmige | German descent | German | Persons of German descent who had remained passive. |

| Eingedeutschte | Voluntarily Germanized | Part-German | Indigenous persons considered by the Nazis as partly Polonized (mainly Silesians and Kashubians); refusal to join this list often led to deportation to a concentration camp |

| Rückgedeutschte | Forcibly Germanized | Part-German | Persons of Polish nationality considered "racially valuable", but who resisted Germanisation |

Hitler who was born in the ethnically diverse Austrian-Hungarian Empire, avowed in Mein Kampf (1926), that Germanising Austrian Slavs by language in the age of Partitions could not have turned them into fully fledged Germans, because no 'Negro' nor a 'Chinaman' would ever 'become German' just because he has learned to speak German. He believed that no visible differences between peoples could be bridged by the use of a common language. Any such attempts would lead to the 'bastardization' of the German element, he said.[74] Likewise, Hitler criticized the previous attempts at Germanisation of the Poles in the Prussian Partition as an erroneous idea, based on the same false reasoning. The Polish people could not possibly be Germanised by being compelled to speak German because they belonged to a different race, he said. "The result would have been fatal" for the purity of the German nation because the foreigners would 'compromise' by their inferiority "the dignity and nobility" of the German nation.[74] During the war, Hitler remarked in his "Table Talk" recorded at the headquarters that people should only be Germanized if they were to improve the German blood line:

There is one cardinal principle. This question of the Germanisation of certain peoples must not be examined in the light of abstract ideas and theory. We must examine each particular case. The only problem is to make sure whether the offspring of any race will mingle well with the German population and will improve it, or whether, on the contrary (as is the case when Jew blood is mixed with German blood), negative results will arise. Unless one is completely convinced that the foreigners whom one proposes to introduce into the German community will have a beneficial effect, well, I think it's better to abstain, however strong the sentimental reasons may be which urge such a course on us. There are plenty of Jews with blue eyes and blond hair, and not a few of them have the appearance which strikingly supports the idea of the Germanisation of their kind. It has, however, been indisputably established that, in the case of Jews, if the physical characteristics of the race are sometimes absent for a generation or two, they will inevitably reappear in the next generation.[76]

Informed by the blood and soil (Blut und Boden) beliefs of ethnic identity—a philosophic basis of Lebensraum—Nazi policy required destroying the USSR for the lands of Russia to become the granary of Germany. The Germanisation of Russia required the destruction of the cities, in an effort to vanquish Russianness, Communism, and Jewish Bolshevism.[77] To that effect, Hitler ordered the Siege of Leningrad (September 1941 – January 1944), to raze the city and destroy the native Russian population.[78] Geopolitically, the establishment of German Lebensraum in the east of Europe would thwart blockades, like those occurred in the First World War, which starved the people of Germany.[79] Moreover, using Eastern Europe to feed Germany also was intended to exterminate millions of Slavs, by slave labour and starvation.[80] When deprived of producers, a workforce, and customers, native industry would cease and disappear from the Germanised region, which then became agricultural land for settlers from Nazi Germany.[80]

The Germanised lands of Eastern Europe would be settled by the Wehrbauer, a soldier–peasant who was to maintain a fortified line of defence, which would prevent any non–German civilisation from arising to threaten the Greater Germanic Reich.[81] Plans for the Germanisation of western Europe were less severe, as the Nazis needed the collaboration of the local political and business establishments, especially that of local industry and their skilled workers. Moreover, Nazi racial policies considered the populations of western Europe more racially acceptable to Aryan standards of "racial purity". In practice, the number and assortment of Nazi racial categories indicated that "East is bad and West is acceptable"; thus, a person's "race" was a matter of life or death in a country under Nazi occupation.[82]

The racist ideology of Lebensraum also comprised the North German racial stock of the northern-European peoples of Scandinavia (Denmark, Norway, Sweden); and the continental-European peoples of Alsace and Lorraine, Belgium and northern France; whilst the United Kingdom would either be annexed or be made a puppet state.[83] Moreover, the poor military performance of the Italian armed forces forced Fascist Italy's withdrawal from the war in 1943, which then made northern Italy a territory to be annexed to the Greater Germanic Reich.[83]

- Collaborationism

For political expediency, the Nazis continually modified their racist politics towards non–Germanic peoples, and so continually redefined the ideological meaning of Lebensraum, in order to collaborate with other peoples, in service to Reich foreign policy. Early in his career as leader of the Nazis, Adolf Hitler said he would accept friendly relations with the USSR, on condition that the Soviet government re-establish the disadvantageous borders of European Russia, which were demarcated in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918), which made possible the restoration of Russo–German diplomatic relations.[84]

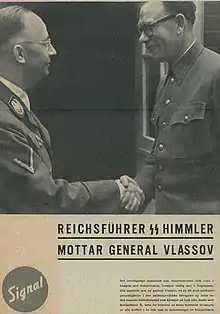

In the 1921–22 period, Hitler said that German Lebensraum might be achieved with a smaller USSR, created by sponsoring anti-communist Russians in deposing the Communist government of the Bolsheviks; however, by the end of 1922, Hitler changed his opinion when there arose the possibility of an Anglo–German geopolitical alliance to destroy the USSR.[84] Yet, once Operation Barbarossa (1941) launched the invasion of the USSR, the strategic stance of the Nazi régime towards a smaller, independent Russia was affected by political pressure from the German Army, who asked Hitler, the supreme military commander, to endorse the creation and integration, to Wehrmacht operations in Russia, of the anti–Communist Russian Liberation Army (ROA); an organisation of defectors, led by General Andrey Vlasov, who meant to depose the régime of Josef Stalin and the Russian Communist Party.[85]

Initially, Hitler rejected the idea of collaborating with the peoples in the East.[86] However, Nazis such as Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg were in favour of collaboration against Bolshevism and offering some independence to the peoples of the East.[87][88] In 1940, Himmler opened up membership for people he regarded as being of "related stock", which resulted in a number of right-wing Scandinavians signing up to fight in the Waffen-SS. When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, further volunteers from France, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, and Croatia signed up to fight for the Nazi cause.[89] After 1942, when the war turned decisively against Nazi Germany, further recruits from the occupied territories signed up to fight for the Nazis.[89] Hitler was worried about the foreign legions on the Eastern Front; he remarked that "One mustn't forget that, unless he is convinced of his racial membership of the Germanic Reich, the foreign legionary is bound to feel that he's betraying his country."[90]

After further losses of manpower, the Nazis tried to persuade the forced foreign laborers in the Reich to fight against Bolshevism, Martin Bormann issued a memorandum on 5 May 1943:

It impossible to win someone over to a new idea while insulting his inner sense of worth at the same time. One cannot expect the highest level of performance from people who are called beasts, barbarians, and subhuman. Instead, positive qualities such as the will to fight Bolshevism, the desire to safeguard one's own existence and that of one's country, commitment and willingness to work are to be encouraged and promoted. Moreover, everything must be done to encourage the necessary cooperation of the European peoples in the fight against Bolshevism.[91]

In 1944, as the German army continually lost battles and territory to the Red Army, the leaders of Nazi Germany, especially Reichsfuhrer-SS Heinrich Himmler, recognised the political, ideological, and military value of the collaborationist Russian Liberation Army in fighting Jewish Bolshevism.[92] Secretly, Himmler in his Posen speeches remarked: "I wouldn't have had any objections, if we had hired Mr. Vlasov and every other Slavic subject wearing a Russian general's uniform, to make propaganda against the Russians. I wouldn't have any objections at all. Wonderful."[61]

Implementation

The Polish Campaign (1 September 1939) was Adolf Hitler's first attempt to achieve Lebensraum for the Germans. The Nazi invasion of Poland consisted of atrocities committed against Polish men, women, and children. Popular German acceptance of the atrocities was achieved by way of Nazi propaganda (print, radio, cinema), a key factor behind the manufactured consent that justified German brutality towards civilians; by continually manipulating the national psychology, the Nazis convinced the German people to believe that Slavs and Jews were Untermenschen.[93]

In autumn 1939, Nazi Germany's implementation of Lebensraum policy began with the Occupation of Poland (1939-1945); in October 1939, Heinrich Himmler became the Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood tasked with returning all ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) to the Reich; preventing harmful foreign influences upon the German people; and to create new settlement areas (especially for returning Volksdeutsche).[94] From mid–1940, the ethnic cleansing (forcible removal) of Poles from the Reichsgau Wartheland initially occurred across the border, to the General Government (a colonial political entity ostensibly autonomous of the Reich), then, after the invasion of the USSR, the displaced Polish populations were jailed in Polenlager (Pole-storage camps) in Silesia and sent to villages designated as ghettoes. In four years of Germanisation (1940–44), the Nazis forcibly removed some 50,000 ethnic Poles from the Polish territories annexed to the Greater German Reich, notably some 18,000–20,000 ethnic Poles from Żywiec County, in Polish Silesia, effected in Action Saybusch.[95][96]

The German population's psychological acceptance of extermination-for-Lebensraum was achieved with propaganda; the leaders of the Hitler Youth were issued pamphlets (e.g. On the German People and its Territory) meant to influence the rank-and-file Hitler Youth about the necessity of Nazi racist practices in obtaining Lebensraum for the German people.[97] Likewise, in the Reich proper, schoolchildren were given propaganda pamphlets (e.g. You and Your People) explaining the importance of Lebensraum for the future of Germany and the German people.[98]

East–West frontier

Concerning the geographic extent of the Greater Germanic Reich, Adolf Hitler rejected the Ural Mountains as an adequate eastern border for Germany, arguing that such mid-sized mountains would not make do as the boundary between the "European and Asiatic worlds", that only a living wall of racially pure Aryans would make do as a border, and that permanent war in the East would "preserve the vitality of the race":

The real frontier is the one that separates the Germanic world from the Slav world. It is our duty to place it where we want it to be. If anyone asks where we obtain the right to extend the Germanic space to the east, we reply that, for a nation, its awareness of what it represents carries this right with it. It is success that justifies everything. The reply to such questions can only be of an empirical nature. It is inconceivable that a higher people should painfully exist on a soil too narrow for it, while amorphous masses, which contribute nothing to civilization, occupy infinite tracts of a soil that is one of the richest in the world ...

We must create conditions for our people that favour its multiplication, and we must, at the same time, build a dike against the Russian flood ... Since there is no natural protection against such a flood, we must meet it with a living wall. A permanent war on the eastern front will help form a sound race of men, and will prevent us from relapsing into the softness of a Europe thrown back upon itself. It should be possible for us to control this region to the east with two hundred and fifty thousand men, plus a cadre of good administrators ...

This space in Russia must always be dominated by Germans.[99]

In 1941, the Reich decided that within two decades, by the year 1961, Poland would have been emptied of Poles and re-populated with ethnic-German colonists from Bukovina, Eastern Galicia, and Volhynia.[100] The ruthless Germanisation Hitler required for Lebensraum was attested in the reports of Wehrbauer (soldier–peasant) colonists' assigned to ethnically cleansed Poland – of finding half-eaten meals at table and unmade beds in the houses given them by the Nazis.[101] Baltic Germans from Estonia and Latvia were evaluated for racial purity; those classified to the highest category, Ost-Falle, were resettled in the Eastern Wall.[102]

| Gau | Total population | Poles | Germans | Jews | Ukrainians | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wartheland | 4,933,600 |

4,220,200 |

324,600 |

384,500 |

– |

4,300 |

| Upper Silesia | 2,632,630 |

2,404,670 |

98,204 |

124,877 |

1,202 |

3,677 |

| Danzig-West Prussia | 1,571,215 |

1,393,717 |

158,377 |

14,458 |

1,648 |

3,020 |

| East Prussia | 1,001,560 |

886,061 |

18,400 |

79,098 |

8,099 |

9,902 |

| Total | 10,139,005 |

8,904,648 |

599,576 |

602,953 |

10,949 |

20,899 |

Moreover, the Germanisation of Russia began with Operation Barbarossa (June–September 1941) meant to conquer and colonise European Russia as the granary of Germany.[105] For those Slavic lands, the Nazi theorist and ideologue Alfred Rosenberg proposed administrative organisation by the Reichskommissariate, countries consolidated into colonial realms ruled by a commissar:

| Reichskommisariat name | Area included |

|---|---|

| Ostland | The Baltic States, Belarus, and western Russia. |

| Ukraine | Ukraine (minus East Galicia and the Romanian-controlled Transnistria Governorate), extended eastwards to the River Volga. |

| Moskowien | The Moscow metropolis and European Russia, exclusive of Karelia and the Kola peninsula, which the Nazis promised to Finland in 1941. |

| Kaukasus | The Caucasus. |

In 1943, in the secret Posen speeches, Heinrich Himmler spoke of the Ural Mountains as the eastern border of the Greater Germanic Reich.[61] That the Germanic race would gradually expand to that eastern border, so that, in several generations' time, the German Herrenvolk, as the leading people of Europe, would be ready to "resume the battles of destiny against Asia", which were "sure to break out again"; and that the defeat of Europe would mean "the destruction of the creative power of the Earth";[61] nonetheless, the Ural Mountains were a secondary objective of the secret Generalplan Ost (Master Plan East) for the colonisation of Eastern Europe.[106] The never-established Reichskommissariat Turkestan would have been the closest territory to Imperial Japan's north-westernmost extents of its own Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with a "living wall" said to be "defending" the easternmost Lebensraum lands, while simultaneously "elevating" higher social class Chinese and nearly all Japanese-ethnicity populations as "honorary Aryans", partly to Hitler's own stated respect in Mein Kampf towards those specific East Asian ethnicities.

The early stages of Lebensraum im Osten (Lebensraum in the East) featured the ethnic-cleansing of Russians and other Slavs (Galicians, Karelians, Ukrainians, et al.) from their lands, and the consolidation of their countries into the Reichskommissariat administration that extended to the Ural Mountains, the geographic frontier of Europe and Asia. To manage the ethnic, racial, and political populations of the USSR, the German Army promptly organized collaborationist, anti-Communist, puppet governments in the Reichskomissariat Ostland (1941–45) and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine (1941–44). Nonetheless, despite the initial, strategic successes of Operation Barbarossa, in counterattack, the Red Army's defeats of the German Army at the Battle of Stalingrad (August 1942 – February 1943) and at the Battle of Kursk (July – August 1943) in Russia, added to the Allied Operation Husky (July – August 1943) in Sicily, thwarted the full implementation of Nazi Lebensraum in the east of Europe.

Historical retrospective

Scale

The scope of the enterprise and the scale of the territories invaded and conquered for Germanisation by the Nazis indicated two ideological purposes for Lebensraum, and their relation to the geopolitical purposes of the Nazis: (i) a program of global conquest, begun in Central Europe; and (ii) a program of continental European conquest, limited to Eastern Europe. From the strategic perspectives of the Stufenplan ("Plan in Stages"), the global- and continental- interpretations of Nazi Lebensraum are feasible, and neither exclusive of each other, nor counter to Hitler's foreign-policy goals for Germany.[107]

Among themselves, within the Reich régime proper, the Nazis held different definitions of Lebensraum, such as the idyllic, agrarian society that required much arable land, advocated by the blood-and-soil ideologist Richard Walther Darré and Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler; and the urban, industrial state, that required raw materials and slaves, advocated by Adolf Hitler.[108] Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of the Soviet Union in summer 1941—required a compromise of concept, purpose, and execution to realize Hitler's conception of Lebensraum in the Slavic lands of Eastern Europe.[107]

During the Posen speeches, Himmler spoke about the deaths of millions of Soviet prisoners of war and foreign labourers:

One basic principle must be the absolute rule for the SS men: We must be honest, decent, loyal and comradely to members of our own blood and to nobody else. What happens to a Russian, to a Czech, does not interest me in the slightest. What other nations can offer in the way of good blood of our type, we will take, if necessary, by kidnapping their children and raising them here with us. Whether nations live in prosperity or starve to death interests me only so far as we need them as slaves for our culture; otherwise, it is of no interest to me. Whether 10,000 Russian females fall down from exhaustion while digging an anti-tank ditch interests me only insofar as the anti-tank ditch for Germany is finished.[61]

Ideology

Racism usually is not a concept integral to the ideology of territorial expansionism; nor to the original meaning of the term Lebensraum ("biological habitat"), as defined by the ethnographer and geographer Friedrich Ratzel. Nonetheless, Nazism, the ideology of the Nazi Party, established racism as a philosophic basis of Lebensraum-as-geopolitics; which Adolf Hitler presented as Nazi racist ideology in his political autobiography Mein Kampf (1926–28). Moreover, the geopolitical interpretations of national living-space of the academic Karl Haushofer (a teacher of Rudolf Hess, Hitler's deputy), provided Adolf Hitler with the intellectual, academic, and scientific rationalisations that justified the territorial expansion of Germany, by the natural right of the German Aryan race, to expand into, occupy, and exploit the lands of other countries, regardless of the native populations.[109] In Mein Kampf, Hitler explained the living-space "required" by Nazi Germany:

In an era when the Earth is gradually being divided up among states, some of which embrace almost entire continents, we cannot speak of a world power in connection with a formation whose political mother country is limited to the absurd area of five hundred thousand square kilometres.[110] Without consideration of traditions and prejudices, Germany must find the courage to gather our people, and their strength, for an advance along the road that will lead this people from its present, restricted living space to new land and soil, and, hence, also free it from the danger of vanishing from the earth, or of serving others as a slave nation.[111] For it is not in colonial acquisitions that we must see the solution of this problem, but exclusively in the acquisition of a territory for settlement, which will enhance the area of the mother country, and hence not only keep the new settlers in the most intimate community with the land of their origin, but secure for the entire area those advantages which lie in its unified magnitude.[112]

Contemporary usages

Since the end of World War II, the term Lebensraum has been used in relation to different countries throughout the world, including China,[113][114] Egypt,[115][116] Israel,[117][118][119][120][121] Poland[122] and the United States.[123]

See also

- Colonialism

- Expansionism for expansionist ideas in other countries

- Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United States

- Imperialism

- Irredentism

- A land without a people for a people without a land

- Malthusianism

Nazi Germany

- Drang nach Osten

- Generalplan Ost

- Greater Germany

- Greater Germanic Reich

- Hunger Plan

- Anschluss

- Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany (1939–1944)

- Volk ohne Raum

- Wehrbauer, settlers of some of the Lebensraum lands

Empire of Japan

- Hakkō ichiu

- An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere of the Empire of Japan

- Jewish settlement in the Japanese Empire before and during World War II

Fascist Italy

- Fourth Shore

- Imperial Italy

- Mare Nostrum

- Manifesto of Race

- Spazio vitale, the equivalent of Lebensraum in Fascist Italy

Soviet Union

United States

Communist/Nationalist China

- Greater China

- Zhonghua minzu

- Chinese expansionism

Turkey

- Neo-Ottomanism

Post-Soviet Russia

- Eurasianism

Footnotes

- "Utopia: The 'Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation'". Munich and Berlin: Institut für Zeitgeschichte. 1999. Archived from the original on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- William Mallinson; Zoran Ristic (2016). The Political Poisoning of Geography. The Threat of Geopolitics to International Relations: Obsession with the Heartland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 3 (19 / 30 in PDF). ISBN 978-1-4438-9738-9. Archived from the original on 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2017-01-24. [Also in:] Gearóid Ó Tuathail; Gerard Toal (1996). Critical Geopolitics: The Politics of Writing Global Space. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0816626038 – via Google Books.

- Graham Evans; Jeffrey Newnham, eds. (1998). Penguin Dictionary of International relations. Penguin Books. p. 301. ISBN 978-0140513974. Geopolitics (excerpt).

- Woodruff D. Smith. The Ideological Origins of Nazi Imperialism. Oxford University Press. p. 84.

- Allan Bullock & Stephen Trombley, ed. "Lebensraum." The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (1999), p. 473.

- André Mineau (2004). Operation Barbarossa: Ideology and Ethics Against Human Dignity. Rodopi. p. 180. ISBN 978-9042016330 – via Google Books.

- Shelley Baranowski (2011). Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0521857390 – via Google Books.

- Jeremy Noakes (March 30, 2011). "BBC – History – World Wars: Hitler and Lebensraum in the East".

- "Lebensraum". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Mark Mazower (2013) [2008]. Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. Penguin UK. p. 431. ISBN 978-0141917504 – via Google Books.

- Michael Heffernan, "Fin de Siècle, Fin du Monde? On the Origins of European Geopolitics; 1890–1920", Geopolitical Traditions: A Century of Geopolitical Thought, (eds. Klaus Dodds, & David A. Atkinson, London & New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 45.

- Holger H. Herwig, "Geopolitik: Haushofer, Hitler and Lebensraum", Geopolitics, Geography and Strategy (eds. Colin Gray & Geoffrey Sloan, London & Portland: Frank Cass, 1999), p. 220.

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1993). pp. 2282–83.

- Robert Millward. The State and Business in the Major Powers: An Economic History, 1815–1939. Routledge, 2013. p108.

- Smith, Woodruff D. (February 1980). "Friedrich Ratzel and the Origins of Lebensraum". German Studies Review. 3 (1): 51–68. doi:10.2307/1429483. JSTOR 1429483.

- Vincent, C. Paul (1997). A Historical Dictionary Of Germany's Weimar Republic, 1918–1933. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 511–13.

- Wanklyn, Harriet. Friedrich Ratzel: A Biographical Memoir and Bibliography. London: Cambridge University Press. (1961) pp. 36–40. ASIN B000KT4J8K

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed., vol. 9, p. 955.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed., vol. 6, p. 901.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich (2004) p. 35. ISBN 1-59420-004-1.

- Stephen J. Lee. Europe, 1890–1945. P. 237.

- Fest, Joachim, 1926 – 2006., And so we National Socialists consciously draw a line beneath the foreign policy tendency of our pre-War period. We take up where we broke off six hundred years ago. We stop the endless German movement to the south and west, and turn our gaze toward the land in the east. At long last we break off the colonial and commercial policy of the pre-War period and shift to the soil policy of the future. If we speak of soil in Europe today, we can primarily have in mind only Russia and her vassal border states (2013). Hitler. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-544-19554-7. OCLC 1021362956.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Germans must remember the truth about Ukraine – for their own sake". www.eurozine.com. The first is that Ukraine was the major war aim. Ukraine was the centre of Hitler’s ideological colonialism, according to Timothy Snyder. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Carsten, F.L. Review of Griff nach der Weltmacht, pp. 751–753, in the English Historical Review, volume 78, Issue No. 309, October 1963, pp. 752–753

- Hillgruber, Andreas. Germany and the Two World Wars, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981 pp. 41–47

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas (2000). A History of Russia (sixth ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 458. ISBN 0-19-512179-1.

- Spartacus Educational: Treaty of Brest-Litovsk Archived 2007-10-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- A Companion to World War I, p. 436.

- Hillgruber, Andreas. Germany and the Two World Wars, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981 pp. 46–47.

- Moses, John. "The Fischer Controversy", pp. 328–29, in Modern Germany: An Encyclopedia of History, People and Culture, 1871–1990, Volume 1, Dieter Buse and Juergen Doerr, eds. Garland Publishing: New York, 1998, p. 328.

- See Raffael Scheck, Germany 1871–1945: A Concise History (2008)

- Immanuel Geiss Tzw. polski pas graniczny 1914–1918. Warszawa (1964).

- Alan J. Taylor (1976) [1963]. The Origins of the Second World War. London: Hamish Hamiltion. p. 23. ISBN 9780141927022.

Second Thoughts (Foreword, 1963 Ed.)

- Paul Weindling (1993). Health, Race and German Politics Between National Unification and Nazism, 1870–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-42397-7.

- Robert Cecil, The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology p69 ISBN 0-396-06577-5

- Lisa Pine (2010). Education in Nazi Germany. Berg. p. (48), 1893. ISBN 978-1-84520-265-1.

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe 1933–1936, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1970 pp. 166–68

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh "Hitler's War Aims" pp. 235–50 in Aspects of the Third Reich, edited by H.W. Koch, Macmillan Press: London, United Kingdom, 1985 pp. 242–45.

- Anthony Read, The Devil's Disciples, p. 159.

- Hitler, Adolf, Mein Kampf, Houghton Mifflin, 1971, p. 646. ISBN 978-0-395-07801-3.

- Roberts, Andrew. The Storm of War, p. 144. ISBN 978-0-06-122859-9

- Shelley Baranowski (2011). Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0521857390.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Volume Two – The National Socialist Movement, Chapter XIV: Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy

- Snyder, Timothy (8 March 2017). "Hitler's American Dream: Adapted from Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning". Slate.com. Tim Duggan Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Minutes of Hitler Conference, 17 October 1941 reproduced in Czesław Madajczyk, ed., Generalny Plan Wschodni: Zbiór dokumentów (Warszawa: Glówna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce, 1990)

- Adolf Hitler, Zweites Buch, p.26

- Adolf Hitler, Zweites Buch, p.29

- Messerschmidt, Manfred "Foreign Policy and Preparation for War" from Germany and the Second World War, Volume I, Clarendon Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 1990 pp. 551–54.

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1970 pp. 26–27.

- Hitler-quotation recorded by Curt Liebmann on February 3, 1933: “How shall political power be used once it has been won. Cannot be decided now. Maybe fighting for new export opportunities, maybe -– and probably better -– conquering new Lebensraum in the East and its ruthless Germanisation.” Source: Wolfgang Michalka: Deutsche Geschichte 1933–1945. Dokumente zur Innen- und Außenpolitik. Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-50234-9, p. 17f. Vgl. Thilo Vogelsang: Neue Dokumente zur Geschichte der Reichswehr 1930–1933. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 2, 1954, Volume 4, p. 397–436, esp. p. 435. Original quotation in German: „Wie soll pol. Macht, wenn sie gewonnen ist, gebraucht werden? Jetzt noch nicht zu sagen. Vielleicht Erkämpfung neuer Export-Mögl., vielleicht – und wohl besser – Eroberung neuen Lebensraumes im Osten u. dessen rücksichtslose Germanisierung.“

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970 pp. 12–13.

- Richard Bessel, Nazism and War, p 36 ISBN 0-679-64094-0

- Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 1970 pp. 6–7.

- Jäckel, Eberhard Hitler's World View A Blueprint for Power Harvard University Press: Cambridge, USA, 1981 pp. 34–35

- Poprzeczny, J. (2004), Odilo Globocnik, Hitler's Man in the East, pp. 42–43, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1625-4

- Richard Weikart, Hitler's Ethic, p.167

- Peter Longerich, Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews, p. 150.

- Document 864-PS [translation]", in Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression. Volume III: Documents 001-PS-1406-PS. District of Columbia: GPO, 1947. pp. 619–621.

- Tomasz Szarota. "Polen unter deutscher Besatzung, 1939–1941" – Vergleichende Betrachtung (in German); p. 43. – "Es muss auch der letzten Kuhmagd in Deutschland klargemacht werden, dass das Polentum gleichwertig ist mit Untermenschentum. Polen, Juden und Zigeuner stehen auf der gleichen unterwertigen Stufe." Propaganda Ministry (October 24, 1939), Order No. 1306, [in:] Bernd Wegner (1991). Zwei Wege nach Moskau: Vom Hitler-Stalin-Pakt bis zum "Unternehmen Barbarossa". München/Zürich: Piper Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3492113465.

- Stein, George H. (1966). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Cornell University Press. pp. 126–127.

When you, my friends, are fighting in the East, you keep that same fight against the same subhumans, against the same inferior races that once appeared under the name of Huns, and later—1,000 years ago during the time of King Henry and Otto I—the name of the Hungarians, and later under the name of Tatars, and then they came again under the name of Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Today, they are called Russian under the political banner of Bolshevism. (Heinrich Himmler speaking to SS soldiers, July 13, 1941, Stettin. Wikiquote.).

- Volume 7. Nazi Germany, 1933–1945 Excerpt from Himmler's Speech to the SS-Gruppenführer at Posen (4 October 1943). German History in Documents and Images. Retrieved 06 June 2016.

- Koon, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience, p. 260.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich at War: 1939–1945, p. 351.

- Robert Gellately (8 March 2001). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-160452-2.

- Robert Gellately (1990). The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy, 1933–1945. Clarendon Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-820297-4.

- Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, p 543 ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- Mark Mazower, Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe, p. 181.

- Himmler, Heinrich. (25 May 1940). Reflections on the Treatment of Peoples of Alien Races in the East. Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law (US Government Printing Office, District of Columbia). pp. 147–150, No. 10. Vol. 13.

- Hitler's plans for Eastern Europe

- Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, p. 543–4 ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius. The German Myth of the East: 1800 to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 187

- Lynn H. Nicholas. Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. New York: Vintage, 2006, p. 241.

- Peter Longerich Heinrich Himmler: A Life (2012), p. 515

- Hitler (2016), pp. 240–241, Volume II: The State.

- Lynn H. Nicholas (2011). Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 194. ISBN 978-0307793829 – via Google Books.

- Hitler's Table Talk, p.475

- Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p 35–36 ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- Edwin P. Hoyt, Hitler's War p 187 ISBN 0-07-030622-2

- Richard Bessel, Nazism and War, p 60 ISBN 0-679-64094-0

- Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p 45 ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- Robert Cecil, The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology p 190 ISBN 0-396-06577-5

- Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p 263 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders p 11 ISBN 0-521-85254-4

- Peter D. Stachura. The Shaping of the Nazi State. p. 31.

- Geoffrey A. Hosking. Rulers and Victims: The Russians in the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press, 2006 P. 213.

- Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History, p, 544, p.551

- Ulrich Herbert, Hitler's Foreign Workers: Enforced Foreign Labor in Germany Under the Third Reich, p. 260–261

- Robert Edwin Herzstein, The war that Hitler won: Goebbels and the Nazi media campaign, p.364

- The Waffen-SS. worldmediarights.com. Gladiators of World War II. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Trevor-Roper, Gerhard L. Weinberg, Hitler's Table Talk 1941–1944: Secret Conversations, p.305

- "Martin Bormann's Circular of May 5, 1943, which included a Memorandum on the General Principles Governing the Treatment of Foreign Laborers Employed in the Reich (dated April 15, 1943)".

- Andreyev, Catherine (1989). Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement: Soviet Reality and Emigré Theories. First paperback edition. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 53, 61. ISBN 978-0521389600.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich at War, p. 102

- Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler: A Life, p. 528.

- Anna Machcewicz (16 February 2010). "Mama wzięła ino chleb". Historia. Tygodnik Powszechny. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Mirosław Sikora (20 September 2011). "Saybusch Aktion – jak Hitler budował raj dla swoich chłopów". OBEP Institute of National Remembrance, Katowice (in Polish). Redakcja Fronda.pl. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- "On the German People and its Territory" (in German). Vom deutschen Volk und seinem Lebensraum, Handbuch für die Schulung in der HJ. 1937.

- Fritz Bennecke, ed. (1940). "You and Your People (Volk)". Vom deutschen Volk und seinem Lebensraum, Handbuch für die Schulung in der HJ (in German). Munich: Franz Eher, 1937.

- Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order, pp. 327–329.

- Volker R. Berghahn "Germans and Poles 1871–1945" in Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences, Rodopi 1999.

- Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web pp. 213–14 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- Nicholas, p. 213

- The Western Review, Supp. Number for Abroad, July and August, 1947 page 49.

- Czesław Madajczyk. Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce pages 234–286 volume 1, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa, 1970

- Madajczyk, Czesław. "Die Besatzungssysteme der Achsenmächte. Versuch einer komparatistischen Analyse" in Studia Historiae Oeconomicae vol. 14 (1980): pp. 105–122, quoted in Gerd R. Ueberschär and Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hitler's War in the East, 1941–1945: A Critical Assessment Berghahn Books, 2008 (review ed.). ISBN 1-84545-501-0.

- Madajczyk, Czeslaw (1962). General Plan East: Hitler's Master Plan For Expansion. Polish Western Affairs, Vol. III No 2.

- Ian Kershaw (2015). The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 134, 155. ISBN 978-1474240963 – via Google Books.

- Kershaw 2015, pp. 244–45

- Rosenberg, Matt (November 1, 2008). "Geopolitics." About.com.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1971, page 644

- Hitler, p. 646

- Hitler, p. 653

- Ian G. Cook; Geoffrey Murray (2001). China's Third Revolution: Tensions in the Transition Towards a Post-Communist China. Psychology Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7007-1307-3.

- Orville Schell; David L. Shambaugh (1999). The China Reader: The Reform Era. Random House. pp. 607–8. ISBN 978-0-307-76622-9.

- Gabriel R. Warburg, Uri M. Kupferschmidt (1983). "Islam Nationalism and Radicalism in Egypt and the Sudan". Praeger. p. 217.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - John Marlowe (1961). "Arab Nationalism and British Imperialism". Praeger. p. 78.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Krämer, Gudrun (2011). A History of Palestine: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Founding of the State of Israel. Princeton University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-691-15007-9.

- Finkelstein, Norman (1995). Image and Reality of the Israel–Palestine Conflict. Verso Books. pp. xxix. ISBN 978-1-85984-442-7.

- Bidwell (1998). Dictionary of Modern Arab History. Routledge. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-7103-0505-3.

The Israeli government began to expropriate more Arab land as Lebensraum for Jewish agricultural rather than strategic settlements and to take water traditionally used by local farmers. A particularly unjust example led to the Land Day Riots of March 1976 but in 1977 Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon stated that there was a long term plan to settle 2 million Jews in the occupied Territories by 2000: this was an ideological pursuit of Greater Israel.

- El-Din El-Din Haseeb, Khair (2012). The Future of the Arab Nation: Challenges and Options: Volume 2. Routledge. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-136-25185-6.

In light of Israel's international relations and its broad regional concept of Lebensraum, it will retain and even improve the degree of its military superiority.

- Graham, Stephen (2004). Cities, War and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics (Studies in Urban and Social Change). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 204. doi:10.1002/9780470753033.index. ISBN 978-1-4051-1575-9.

Eitam argues that, ultimately, Israel should strive to force or 'persuade' all Arabs and Palestinians to leave Israel and the occupied territories—to be accommodated in Jordan and the Sinai (Egypt) ... Eitam has even explicitly used the German concept of Lebensraum (living space)—a cornerstone of the Holocaust—to underpin his arguments.

- Balogun, Bolaji (2017). "Polish Lebensraum: the colonial ambition to expand on racial terms" (PDF). Ethnic and Racial Studies. 41 (14): 1–19. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1392028. S2CID 148720825.

- Neil Smith, American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization, (Berkeley & Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2003), p 27-28.

References

- Hitler, Adolf (March 21, 1939). Mein Kampf. Introduction by James Vincent Murphy, the Irish translator of Mein Kampf who worked in Goebbels's Ministry of Propaganda from 1934 to 1938 (died 1946). Hurst and Blackett. The copy contains both, Volume 1: A Retrospect, and Volume 2: The national Socialist Movement, fully unexpurgated; in text file format without pagination. Reprinted in 1939 (before the US entered the war) by Houghton Mifflin, Boston Massachusetts. This book is still banned from publication in Germany – via Project Gutenberg Australia.

Note: The term Lebensraum, as loan-word adopted in the English historiography long after World War II ended, does not appear in the first prewar translation of the original.

[Also:] Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler (DjVu). Introduction by John Chamberlain et al. Reynal A Hitchcock; published by arrangement with Houghton Mifflin Company. 1941. Paginated, Complete and Unabridged – via Internet Archive.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) [And:] Mein Kampf. Houghton Mifflin. 1971. ISBN 978-0-395-07801-3. [As well as:] Hitler, Adolf (2016). Mein Kampf. Adolf Hitler. ISBN 978-6050418347 – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Kamenetsky, Ihor (1961). Secret Nazi Plans for Eastern Europe: A Study of Lebensraum Policies. New York City: Bookman Associates.

External links

- The Invasion of the Soviet Union and the Beginnings of Mass Murder Archived 2012-12-28 at archive.today, in the Yad Vashem website

- Utopia: The Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation—A map of Nazi plans for German empire

- Hitler and Lebensraum in the East, by Jeremy Noakes