Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering;[lower-alpha 1] German: [ˈɡøːʁɪŋ] (![]() listen); 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1945.

listen); 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1945.

Hermann Göring | |

|---|---|

Göring on trial, c. 1946 | |

| 16th President of the Reichstag | |

| In office 30 August 1932 – 23 April 1945 | |

| President | Paul von Hindenburg (1932–1934) |

| Führer | Adolf Hitler (1934–1945) |

| Chancellor |

|

| Preceded by | Paul Löbe |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished

|

| Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe | |

| In office 1 March 1935 – 24 April 1945 | |

| Führer | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Robert Ritter von Greim |

| Reichsstatthalter of Prussia Acting | |

| In office 25 April 1933[1] – 23 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Adolf Hitler |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Ministerpräsident of Prussia | |

| In office 11 April 1933 – 23 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Franz von Papen (Reichskommissar) |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Additional positions | |

| 1939–1945 | Chair of the Ministerial Council for Reich Defense[2] |

| 1937–1938 | Reichsminister of Economics |

| 1936–1945 | Reich Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan[3] |

| 1934–1945 | Reichsminister of Forestry |

| 1933–1945 | Reichsminister of Aviation |

| 1923 | Oberste SA-Führer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hermann Wilhelm Göring 12 January 1893 Rosenheim, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 15 October 1946 (aged 53) Nuremberg Prison, Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany |

| Cause of death | Suicide by cyanide poisoning |

| Political party | Nazi Party (1922–1945) |

| Spouses | Carin von Kantzow

(m. 1923; died 1931)Emmy Sonnemann

(m. 1935) |

| Children | Edda Göring |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Albert Göring (brother) |

| Residence | Carinhall |

| Alma mater | University of Munich |

| Occupation |

|

| Cabinet | Hitler Cabinet |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands | Jagdgeschwader 1 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Criminal conviction | |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Conspiracy to commit crimes against peace Crimes of aggression War crimes Crimes against humanity |

| Trial | Nuremberg trials |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

A veteran World War I fighter pilot ace, Göring was a recipient of the Pour le Mérite ("The Blue Max"). He was the last commander of Jagdgeschwader 1 (Jasta 1), the fighter wing once led by Manfred von Richthofen. An early member of the Nazi Party, Göring was among those wounded in Adolf Hitler's failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. While receiving treatment for his injuries, he developed an addiction to morphine which persisted until the last year of his life. After Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Göring was named as minister without portfolio in the new government. One of his first acts as a cabinet minister was to oversee the creation of the Gestapo, which he ceded to Heinrich Himmler in 1934.

Following the establishment of the Nazi state, Göring amassed power and political capital to become the second most powerful man in Germany. He was appointed commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe (air force), a position he held until the final days of the regime. Upon being named Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan in 1936, Göring was entrusted with the task of mobilizing all sectors of the economy for war, an assignment which brought numerous government agencies under his control. In September 1939, Hitler designated him as his successor and deputy in all his offices. After the Fall of France in 1940, he was bestowed the specially created rank of Reichsmarschall, which gave him seniority over all officers in Germany's armed forces.

By 1941, Göring was at the peak of his power and influence. As the Second World War progressed, Göring's standing with Hitler and with the German public declined after the Luftwaffe proved incapable of preventing the Allied bombing of Germany's cities and resupplying surrounded Axis forces in Stalingrad. Around that time, Göring increasingly withdrew from military and political affairs to devote his attention to collecting property and artwork, much of which was stolen from Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Informed on 22 April 1945 that Hitler intended to commit suicide, Göring sent a telegram to Hitler requesting his permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Considering his request an act of treason, Hitler removed Göring from all his positions, expelled him from the party, and ordered his arrest. After the war, Göring was convicted of conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials in 1946. He was sentenced to death by hanging, but committed suicide by ingesting cyanide hours before the sentence was to be carried out.

Early life and education

Göring was born on 12 January 1893[4] at the Marienbad Sanatorium in Rosenheim, Bavaria. His father, Heinrich Ernst Göring (31 October 1839 – 7 December 1913), a former cavalry officer, had been the first governor-general of German South West Africa (modern-day Namibia).[5] Heinrich had three children from a previous marriage. Göring was the fourth of five children by Heinrich's second wife, Franziska Tiefenbrunn (1859–15 July 1943), a Bavarian peasant. Göring's elder siblings were Karl, Olga, and Paula; his younger brother was Albert. At the time that Göring was born, his father was serving as consul general in Haiti, and his mother had returned home briefly to give birth. She left the six-week-old baby with a friend in Bavaria and did not see the child again for three years, when she and Heinrich returned to Germany.[6]

Göring's godfather was Hermann Epenstein, a wealthy Jewish physician and businessman his father had met in Africa. Epenstein provided the Göring family, who were surviving on Heinrich's pension, first with a family home in Berlin-Friedenau,[7] and then a small castle called Veldenstein, near Nuremberg. Göring's mother became Epenstein's mistress around this time, and remained so for some fifteen years. Epenstein acquired the minor title of Ritter (knight) von Epenstein through service and donations to the Crown.[8]

Interested in a career as a soldier from a very early age, Göring enjoyed playing with toy soldiers and dressing up in a Boer uniform his father had given him. He was sent to boarding school at age eleven, where the food was poor and discipline was harsh. He sold a violin to pay for his train ticket home, and then took to his bed, feigning illness, until he was told he would not have to return.[9] He continued to enjoy war games, pretending to lay siege to the castle Veldenstein and studying Teutonic legends and sagas. He became a mountain climber, scaling peaks in Germany, at the Mont Blanc massif, and in the Austrian Alps. At age 16, he was sent to a military academy at Berlin Lichterfelde, from which he graduated with distinction.[10]

Göring joined the Prince Wilhelm Regiment (112th Infantry, Garrison: Mülhausen) of the Prussian Army in 1912. The next year his mother had a falling-out with Epenstein. The family was forced to leave Veldenstein and moved to Munich; Göring's father died shortly afterwards. When World War I began in August 1914, Göring was stationed at Mülhausen with his regiment.[10]

World War I

During the first year of World War I, Göring served with his infantry regiment in the area of Mülhausen, a garrison town less than 2 km from the French frontier. He was hospitalized with rheumatism, a result of the damp of trench warfare. While he was recovering, his friend Bruno Loerzer convinced him to transfer to what would become, by October 1916, the Luftstreitkräfte (transl. air combat forces) of the German army, but his request was turned down. Later that year, Göring flew as Loerzer's observer in Feldflieger Abteilung 25 (FFA 25); Göring had informally transferred himself. He was discovered and sentenced to three weeks' confinement to barracks, but the sentence was never carried out. By the time it was supposed to be imposed, Göring's association with Loerzer had been made official. They were assigned as a team to FFA 25 in the Crown Prince's Fifth Army. They flew reconnaissance and bombing missions, for which the Crown Prince invested both Göring and Loerzer with the Iron Cross, first class.[11]

After completing the pilot's training course, Göring was assigned to Jagdstaffel 5. Seriously wounded in the hip in aerial combat, he took nearly a year to recover. He then was transferred to Jagdstaffel 26, commanded by Loerzer, in February 1917. He steadily scored air victories until May, when he was assigned to command Jagdstaffel 27. Serving with Jastas 5, 26 and 27, he continued to win victories. In addition to his Iron Crosses (1st and 2nd Class), he received the Zähringer Lion with swords, the Friedrich Order, the House Order of Hohenzollern with swords third class, and finally, in May 1918, the coveted Pour le Mérite.[12] According to Hermann Dahlmann, who knew both men, Göring had Loerzer lobby for the award.[13] He finished the war with 22 victories.[14] A thorough post-war examination of Allied loss records showed that only two of his awarded victories were doubtful. Three were possible and 17 were certain, or highly likely.[15]

On 7 July 1918, following the death of Wilhelm Reinhard, successor to Manfred von Richthofen, Göring was made commander of the "Flying Circus", Jagdgeschwader 1.[16] His arrogance made him unpopular with the men of his squadron.[17]

In the last days of the war, Göring was repeatedly ordered to withdraw his squadron, first to Tellancourt airdrome, then to Darmstadt. At one point, he was ordered to surrender the aircraft to the Allies; he refused. Many of his pilots intentionally crash-landed their planes to keep them from falling into enemy hands.[18]

Like many other German veterans, Göring was a proponent of the stab-in-the-back myth, the belief which held that the German Army had not really lost the war, but instead was betrayed by the civilian leadership: Marxists, Jews, and especially the republicans, who had overthrown the German monarchy.[19]

After World War I

Göring remained in aviation after the war. He tried barnstorming and briefly worked at Fokker. After spending most of 1919 living in Denmark, he moved to Sweden and joined Svensk Lufttrafik, a Swedish airline. Göring was often hired for private flights. During the winter of 1920–1921, he was hired by Count Eric von Rosen to fly him to his castle from Stockholm. Invited to spend the night, Göring may at this time have first seen the swastika emblem, which Rosen had set in the chimney piece as a family badge.[20][lower-alpha 2]

This was also the first time that Göring saw his future wife; the count introduced his sister-in-law, Baroness Carin von Kantzow (née Freiin von Fock). Estranged from her husband of ten years, she had an eight-year-old son. Göring was immediately infatuated and asked her to meet him in Stockholm. They arranged a visit at the home of her parents and spent much time together through 1921, when Göring left for Munich to take political science at the university. Carin obtained a divorce, followed Göring to Munich, and married him on 3 February 1922.[21] Their first home together was a hunting lodge at Hochkreuth in the Bavarian Alps, near Bayrischzell, some 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Munich.[22] After Göring met Adolf Hitler and joined the Nazi Party in 1922, they moved to Obermenzing, a suburb of Munich.[23]

Early Nazi career

Göring joined the Nazi Party in 1922 after hearing a speech by Hitler.[23][24] He was given command of the Sturmabteilung (SA) as the Oberster SA-Führer in 1923.[25] He was later appointed an SA-Gruppenführer (Lieutenant general) and held this rank on the SA rolls until 1945. At this time, Carin—who liked Hitler—often played hostess to meetings of leading Nazis, including her husband, Hitler, Rudolf Hess, Alfred Rosenberg, and Ernst Röhm.[26] Hitler later recalled his early association with Göring:

I liked him. I made him the head of my SA. He is the only one of its heads that ran the SA properly. I gave him a dishevelled rabble. In a very short time he had organised a division of 11,000 men.[27]

Hitler and the Nazi Party held mass meetings and rallies in Munich and elsewhere during the early 1920s, attempting to gain supporters in a bid for political power.[28] Inspired by Benito Mussolini's March on Rome, the Nazis attempted to seize power on 8–9 November 1923 in a failed coup known as the Beer Hall Putsch. Göring, who was with Hitler leading the march to the War Ministry, was shot in the groin.[29] Fourteen Nazis and four policemen were killed; many top Nazis, including Hitler, were arrested.[30] With Carin's help, Göring was smuggled to Innsbruck, where he received surgery and was given morphine for the pain. He remained in hospital until 24 December.[31] This was the beginning of his morphine addiction, which lasted until his imprisonment at Nuremberg.[32] Meanwhile, the authorities in Munich declared Göring a wanted man. The Görings—acutely short of funds and reliant on the good will of Nazi sympathizers abroad—moved from Austria to Venice. In May 1924 they visited Rome, via Florence and Siena. Göring met Mussolini, who expressed an interest in meeting Hitler, who was by then in prison.[33]

Personal problems continued to multiply. By 1925, Carin's mother was ill. The Görings—with difficulty—raised the money in the spring of 1925 for a journey to Sweden via Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Danzig (now Gdańsk). Göring had become a violent morphine addict; Carin's family were shocked by his deterioration. Carin, who was ill with epilepsy and a weak heart, had to allow the doctors to take charge of Göring; her son was taken by his father. Göring was certified a dangerous drug addict and was placed in Långbro asylum on 1 September 1925.[34] He was violent to the point where he had to be confined in a straitjacket, but his psychiatrist felt he was sane; the condition was caused solely by the morphine.[35] Weaned off the drug, he left the facility briefly, but had to return for further treatment. He returned to Germany when an amnesty was declared in 1927 and resumed working in the aircraft industry.[36] Hitler, who had written Mein Kampf while in prison, had been released in December 1924.[37] Carin Göring, ill with epilepsy and tuberculosis,[38] died of heart failure on 17 October 1931.

Meanwhile, the Nazi Party was in a period of rebuilding and waiting. The economy had recovered, which meant fewer opportunities for the Nazis to agitate. The SA was reorganised, but with Franz Pfeffer von Salomon as its head rather than Göring, and the Schutzstaffel (SS) was founded in 1925, initially as a bodyguard for Hitler. Membership in the party increased from 27,000 in 1925 to 108,000 in 1928 and 178,000 in 1929. In the May 1928 elections the Nazi Party only obtained 12 seats out of an available 491 in the Reichstag.[39] Göring was elected as a representative from Bavaria.[40] He continued to be elected to the Reichstag in all subsequent elections during the Weimar and Nazi regimes.[41] The Great Depression led to a disastrous downturn in the German economy, and in the 1930 election, the Nazi Party won 6,409,600 votes and 107 seats.[42] In May 1931, Hitler sent Göring on a mission to the Vatican, where he met the future Pope Pius XII.[43]

In the July 1932 election, the Nazis won 230 seats to become far and away the largest party in the Reichstag. By longstanding tradition, the Nazis were thus entitled to select the President of the Reichstag, and elected Göring to the post.[44] He would retain this position until 23 April 1945.

Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire occurred on the night of 27 February 1933. Göring was one of the first to arrive on the scene. Marinus van der Lubbe, a Communist radical, was arrested and claimed sole responsibility for the fire. Göring immediately called for a crackdown on Communists.[45]

The Nazis took advantage of the fire to advance their own political aims. The Reichstag Fire Decree, passed the next day on Hitler's urging, suspended basic rights and allowed detention without trial. Activities of the German Communist Party were suppressed, and some 4,000 Party members were arrested.[46] Göring demanded that the prisoners should be shot, but Rudolf Diels, head of the Prussian political police, ignored the order.[47] Some researchers, including William L. Shirer and Alan Bullock, are of the opinion that the Nazi Party itself was responsible for starting the fire.[48][49]

At the Nuremberg trials, General Franz Halder testified that Göring admitted responsibility for starting the fire. He said that, at a luncheon held on Hitler's birthday in 1942, Göring said, "The only one who really knows about the Reichstag is I, because I set it on fire!"[50] In his own Nuremberg testimony, Göring denied this story.[51]

Second marriage

During the early 1930s, Göring was often in the company of Emmy Sonnemann, an actress from Hamburg.[52] They were married on 10 April 1935, in Berlin. The wedding was celebrated on a huge scale. A large reception was held the night before at the Berlin Opera House. Fighter aircraft flew overhead on the night of the reception and the day of the ceremony,[53] at which Hitler was best man.[54] Göring's daughter, Edda, was born on 2 June 1938.[55]

Nazi potentate

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

|

When Hitler was named chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, Göring was appointed as Reichsminister without portfolio and Reichskommissar of Aviation.[56] This was followed on 11 April 1933 by his appointment as Minister-President of Prussia, Prussian interior minister and chief of the Prussian police.[57] In October 1933, Göring was made a member of Hans Frank's Academy for German Law at its inaugural meeting.[58]

Wilhelm Frick, the Reich interior minister, and the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, hoped to create a unified police force for all of Germany, but Göring on 26 April 1933 established a special Prussian police force, with Rudolf Diels at its head. The force was called the Geheime Staatspolizei (transl. Secret State Police), or Gestapo. Göring, thinking that Diels was not ruthless enough to use the Gestapo effectively to counteract the power of the SA, handed over control of the Gestapo to Himmler on 20 April 1934.[59] By this time, the SA numbered over two million men.[60]

Hitler was deeply concerned that Ernst Röhm, the chief of the SA, was planning a coup. Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich plotted with Göring to use the Gestapo and SS to crush the SA.[61] Members of the SA got wind of the proposed action and thousands of them took to the streets in violent demonstrations on the night of 29 June 1934. Enraged, Hitler ordered the arrest of the SA leadership. Röhm was shot dead in his cell when he refused to commit suicide; Göring personally went over the lists of prisoners—numbering in the thousands—and determined who else should be shot. At least 85 people were killed in the period of 30 June to 2 July, which is now known as the Night of the Long Knives.[62] Hitler admitted in the Reichstag on 13 July that the killings had been entirely illegal, but claimed a plot had been under way to overthrow the Reich. A retroactive law was passed making the action legal. Any criticism was met with arrests.[63]

One of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been in place since the end of World War I, stated that Germany was not allowed to maintain an air force. After the 1926 signing of the Kellogg–Briand Pact, police aircraft were permitted. Göring was appointed Air Traffic Minister in May 1933. Germany began to accumulate aircraft in violation of the Treaty, and in 1935 the existence of the Luftwaffe was formally acknowledged,[64] with Göring as Reich Aviation Minister.[65]

During a cabinet meeting in September 1936, Göring and Hitler announced that the German rearmament programme must be sped up. On 18 October, Hitler named Göring as Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan to undertake this task. Göring created a new organisation to administer the Plan and drew the ministries of labour and agriculture under its umbrella. He bypassed the economics ministry in his policy-making decisions, to the chagrin of Hjalmar Schacht, the minister in charge. Huge expenditures were made on rearmament, in spite of growing deficits.[66] Schacht resigned on 8 December 1937,[67] and Walther Funk took over the position, as well as control of the Reichsbank. In this way, both of these institutions were brought under Göring's control under the auspices of the Four Year Plan.[68] In July 1937, the Reichswerke Hermann Göring was established under state ownership – though led by Göring – with the aim of boosting steel production beyond the level which private enterprise could economically provide.[69]

In 1938, Göring was involved in the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair, which led to the resignations of the War Minister, Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg, and the army commander, General Werner von Fritsch. Göring had acted as witness at Blomberg's wedding to Margarethe Gruhn, a 26-year-old typist, on 12 January 1938. Information received from the police showed that the young bride was a prostitute.[70] Göring felt obligated to tell Hitler, but also saw this event as an opportunity to dispose of Blomberg. Blomberg was forced to resign. Göring did not want Fritsch to be appointed to that position and thus be his superior. Several days later, Heydrich revealed a file on Fritsch that contained allegations of homosexual activity and blackmail. The charges were later proven to be false, but Fritsch had lost Hitler's trust and was forced to resign.[71] Hitler used the dismissals as an opportunity to reshuffle the leadership of the military. Göring asked for the post of War Minister, but was turned down; he was appointed to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall. Hitler took over as supreme commander of the armed forces and created subordinate posts to head the three main branches of service.[72]

As minister in charge of the Four Year Plan, Göring became concerned with the lack of natural resources in Germany, and began pushing for Austria to be incorporated into the Reich. The province of Styria had rich iron ore deposits, and the country as a whole was home to many skilled labourers that would also be useful. Hitler had always been in favour of a takeover of Austria, his native country. He met the Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg on 12 February 1938, threatening invasion if peaceful unification was not forthcoming. The Nazi Party was made legal in Austria to gain a power base, and a referendum on reunification was scheduled for March. When Hitler did not approve of the wording of the plebiscite, Göring telephoned Schuschnigg and Austrian head of state Wilhelm Miklas to demand Schuschnigg's resignation, threatening invasion by German troops and civil unrest by the Austrian Nazi Party members. Schuschnigg resigned on 11 March and the plebiscite was cancelled. By 5:30 the next morning, German troops that had been massing on the border marched into Austria, meeting no resistance.[73]

Although Joachim von Ribbentrop had been named Foreign Minister in February 1938, Göring continued to involve himself in foreign affairs.[55] That July, he contacted the British government with the idea that he should make an official visit to discuss Germany's intentions for Czechoslovakia. Neville Chamberlain was in favour of a meeting, and there was talk of a pact being signed between Britain and Germany. In February 1938, Göring visited Warsaw to quell rumours about the upcoming invasion of Poland. He had conversations with the Hungarian government that summer as well, discussing their potential role in an invasion of Czechoslovakia. At the Nuremberg Rally that September, Göring and other speakers denounced the Czechs as an inferior race that must be conquered.[74] Chamberlain and Hitler had a series of meetings that led to the signing of the Munich Agreement (29 September 1938), which turned over control of the Sudetenland to Germany.[75] In March 1939, Göring threatened Czechoslovak president Emil Hácha with the bombing of Prague. Hácha then agreed to sign a communique accepting the German occupation of the remainder of Bohemia and Moravia.[76]

Although many in the party disliked him,[77] before the war Göring enjoyed widespread personal popularity among the German public because of his perceived sociability, colour and humour.[78][79] As the Nazi leader most responsible for economic matters, he presented himself as a champion of national interests over allegedly corrupt big business and the old German elite. The Nazi press was on Göring's side. Other leaders, such as Hess and Ribbentrop, were envious of his popularity.[78] In Britain and the United States, some viewed Göring as more acceptable than the other Nazis and as a possible mediator between the western democracies and Hitler.[79]

World War II

Success on all fronts

Göring and other senior officers were concerned that Germany was not yet ready for war, but Hitler insisted on pushing ahead as soon as possible.[80] On 30 August 1939, immediately prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, Hitler appointed Göring as the chairman of a new six-person Council of Ministers for Defense of the Reich which was set up to operate as a war cabinet.[81] The invasion of Poland, the opening action of World War II, began at dawn on 1 September 1939.[82] Later in the day, speaking to the Reichstag, Hitler designated Göring as his successor as Führer of all Germany, "If anything should befall me",[83] with Hess as the second alternate.[77] Big German victories followed one after the other in quick succession. With the help of the Luftwaffe, the Polish Air Force was defeated within a week.[84] The Fallschirmjäger seized vital airfields in Norway (Operation Weserübung) and captured Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium on 10 May 1940, the first day of the Battle of France. Göring's Luftwaffe played critical roles in the Battles of the Netherlands, of Belgium and of France in May 1940.[85]

After the Fall of France, Hitler awarded Göring the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross for his successful leadership.[86] During the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony, Hitler promoted Göring to the rank of Reichsmarschall des Grossdeutschen Reiches (transl. Reich Marshal of the Greater German Reich), a specially-created rank which made him senior to all field marshals in the military, including the Luftwaffe. As a result of this promotion, he was the highest-ranking soldier in Germany until the end of the war. Göring had already received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 30 September 1939 as Commander in Chief of the Luftwaffe.[86]

The UK had declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, the third day of the invasion of Poland.[87] In July 1940, Hitler began preparations for an invasion of Britain. As part of the plan, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had to be neutralized. Bombing raids commenced on British air installations and on cities and centres of industry.[88] Göring had by then already announced in a radio speech, "If as much as a single enemy aircraft flies over German soil, my name is Meier!",[89] something that would return to haunt him, when the RAF began bombing German cities on 11 May 1940.[90] Though he was confident the Luftwaffe could defeat the RAF within days, Göring, like Admiral Erich Raeder, commander-in-chief of the Kriegsmarine (navy),[91] was pessimistic about the chance of success of the planned invasion (codenamed Operation Sea Lion).[92] Göring hoped that a victory in the air would be enough to force peace without an invasion. The campaign failed, and Sea Lion was postponed indefinitely on 17 September 1940.[93] After their defeat in the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe attempted to defeat Britain via strategic bombing. On 12 October 1940 Hitler cancelled Sea Lion due to the onset of winter.[94] By the end of the year, it was clear that British morale was not being shaken by the Blitz, though the bombings continued through May 1941.[95]

Decline on all fronts

In spite of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, signed in 1939, Nazi Germany began Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of the Soviet Union—on 22 June 1941. Initially, the Luftwaffe was at an advantage, destroying thousands of Soviet aircraft in the first month of fighting.[96] Hitler and his top staff were sure that the campaign would be over by Christmas, and no provisions were made for reserves of men or equipment.[97] But, by July, the Germans had only 1,000 planes remaining in operation, and their troop losses were over 213,000 men. The choice was made to concentrate the attack on only one part of the vast front; efforts would be directed at capturing Moscow.[98] After the long, but successful, Battle of Smolensk, Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to halt its advance to Moscow and temporarily diverted its Panzer groups north and south to aid in the encirclement of Leningrad and Kiev.[99] The pause provided the Red Army with an opportunity to mobilize fresh reserves; historian Russel Stolfi considers it to be one of the major factors that caused the failure of the Moscow offensive, which was resumed in October 1941 with the Battle of Moscow.[99] Poor weather conditions, fuel shortages, a delay in building aircraft bases in Eastern Europe, and overstretched supply lines were also factors. Hitler did not give permission for even a partial retreat until mid-January 1942; by this time the losses were comparable to those of the French invasion of Russia in 1812.[100]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Göring, along with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Admiral Erich Raeder, urged Hitler to immediately declare war on the United States.[101]

Hitler decided that the summer 1942 campaign would be concentrated in the south; efforts would be made to capture the oilfields in the Caucasus.[102] The Battle of Stalingrad, a major turning point of the war,[103] began on 23 August 1942 with a bombing campaign by the Luftwaffe.[104] The German Sixth Army entered the city, but because of its location on the front line, it was still possible for the Soviets to encircle and trap it there without reinforcements or supplies. When the Sixth Army was surrounded by the end of November in Operation Uranus, Göring promised that the Luftwaffe would be able to deliver a minimum of 300 tons of supplies to the trapped men every day. On the basis of these assurances, Hitler demanded that there be no retreat; they were to fight to the last man. Though some airlifts were able to get through, the amount of supplies delivered never exceeded 120 tons per day.[105][106] The remnants of the Sixth Army—some 91,000 men out of an army of 285,000—surrendered in early February 1943; only 5,000 of these captives survived the Russian prisoner of war camps to see Germany again.[107]

War over Germany

Meanwhile, the strength of the US and British bomber fleets had increased. Based in Britain, they began operations against German targets. The first thousand-bomber raid was staged on Cologne on 30 May 1942.[108] Air raids continued on targets farther from England after auxiliary fuel tanks were installed on US fighter aircraft. Göring refused to believe reports that American fighters had been shot down as far east as Aachen in winter 1942–1943. His reputation began to decline.[109]

The American P-51 Mustang, with a combat radius of over 1,800 miles (2,900 km) when using underwing drop tanks, began to escort the bombers in large formations to and from the target area in early 1944. From that point onwards, the Luftwaffe began to suffer casualties in aircrews it could not sufficiently replace. By targeting oil refineries and rail communications, Allied bombers crippled the German war effort by late 1944.[110] German civilians blamed Göring for his failure to protect the homeland.[111] Hitler began excluding him from conferences, but continued him in his positions at the head of the Luftwaffe and as plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan.[112] As he lost Hitler's trust, Göring began to spend more time at his various residences.[113] On D-Day (6 June 1944), the Luftwaffe only had some 300 fighters and a small number of bombers in the area of the landings; the Allies had a total strength of 11,000 aircraft.[114]

End of the war

As the Soviets approached Berlin, Hitler's efforts to organise the defence of the city became ever more meaningless and futile.[115] His last birthday, celebrated at the Führerbunker in Berlin on 20 April 1945, was the occasion for leave-taking for many top Nazis, Göring included. By this time, Göring's hunting lodge Carinhall had been evacuated, the building destroyed,[116] and its art treasures moved to Berchtesgaden and elsewhere.[117] Göring arrived at his estate at Obersalzberg on 22 April, the same day that Hitler, in a lengthy diatribe against his generals, first publicly admitted that the war was lost and that he intended to remain in Berlin to the end and then commit suicide.[118] He also stated that Göring was in a better position to negotiate a peace settlement.[119]

OKW operations chief Alfred Jodl was present for Hitler's rant, and notified Göring's chief of staff, Karl Koller, at a meeting a few hours later. Sensing its implications, Koller immediately flew to Berchtesgaden to notify Göring of this development. A week after the start of the Soviet invasion, Hitler had issued a decree naming Göring his successor in the event of his death, thus codifying the declaration he had made soon after the beginning of the war. The decree also gave Göring full authority to act as Hitler's deputy if Hitler ever lost his freedom of action.[119]

Göring feared being branded a traitor if he tried to take power, but also feared being accused of dereliction of duty if he did nothing. After some hesitation, Göring reviewed his copy of the 1941 decree naming him Hitler's successor. After conferring with Koller and Hans Lammers (the state secretary of the Reich Chancellery), Göring concluded that by remaining in Berlin to face certain death, Hitler had incapacitated himself from governing. All agreed that under the terms of the decree, it was incumbent upon Göring to take power in Hitler's stead.[120] He was also motivated by fears that his rival, Martin Bormann, would seize power upon Hitler's death and would have him killed as a traitor. With this in mind, Göring sent a carefully worded telegram asking Hitler for permission to take over as the leader of Germany, stressing that he would be acting as Hitler's deputy. He added that, if Hitler did not reply by 22:00 that night (23 April), he would assume that Hitler had indeed lost his freedom of action, and would assume leadership of the Reich.[121]

The telegram was intercepted by Bormann, who convinced Hitler that Göring was a traitor. Bormann argued that Göring's telegram was not a request for permission to act as Hitler's deputy, but a demand to resign or be overthrown.[122] Bormann also intercepted another telegram in which Göring directed Ribbentrop to report to him if there was no further communication from Hitler or Göring before midnight.[123] Hitler sent a reply to Göring—prepared with Bormann's help—rescinding the 1941 decree and threatening him with execution for high treason unless he immediately resigned from all of his offices. Göring duly resigned. Afterwards, Hitler (or Bormann, depending on the source) ordered the SS to place Göring, his staff, and Lammers under house arrest at Obersalzberg.[122][124] Bormann made an announcement over the radio that Göring had resigned for health reasons.[125]

By 26 April, the complex at Obersalzberg was under attack by the Allies, so Göring was moved to his castle at Mauterndorf. In his last will and testament, Hitler expelled Göring from the party, formally rescinded the decree making him his successor, and upbraided Göring for "illegally attempting to seize control of the state."[126] He then appointed Karl Dönitz, the Navy's commander-in-chief, as president of the Reich and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Hitler and his wife, Eva Braun, committed suicide on 30 April 1945, a few hours after a hastily arranged wedding. Göring was freed on 5 May by a passing Luftwaffe unit, and he made his way to the US lines in hopes of surrendering to them rather than to the Soviets. He was taken into custody near Radstadt on 6 May by elements of the 36th Infantry Division of the US Army.[127] This move likely saved Göring's life; Bormann had ordered him executed if Berlin had fallen.[128]

Trial and death

Göring was flown to Camp Ashcan, a temporary prisoner-of-war camp housed in the Palace Hotel at Mondorf-les-Bains, Luxembourg. Here he was weaned off dihydrocodeine (a mild morphine derivative)—he had been taking the equivalent of three or four grains (260 to 320 mg) of morphine a day—and was put on a strict diet; he lost 60 pounds (27 kg). His IQ was tested while in custody and found to be 138.[129] Top Nazi officials were transferred in September to Nuremberg, which was to be the location of a series of military tribunals beginning in November.[130]

Göring was the second-highest-ranking official tried at Nuremberg, behind Reich President (former Admiral) Karl Dönitz. The prosecution levelled an indictment of four charges, including a charge of conspiracy; waging a war of aggression; war crimes, including the plundering and removal to Germany of works of art and other property; and crimes against humanity, including the disappearance of political and other opponents under the Nacht und Nebel (transl. Night and Fog) decree; the torture and ill treatment of prisoners of war; and the murder and enslavement of civilians, including what was at the time estimated to be 5,700,000 Jews. Not permitted to present a lengthy statement, Göring declared himself to be "in the sense of the indictment not guilty."[131]

The trial lasted 218 days. The prosecution presented its case from November through March, and Göring's defence—the first to be presented—lasted from 8 to 22 March. The sentences were read on 30 September 1946.[132] Göring, forced to remain silent while seated in the dock, communicated his opinions about the proceedings using gestures, shaking his head, or laughing. He constantly took notes and whispered with the other defendants, and tried to control the erratic behaviour of Hess, who was seated beside him.[133] During breaks in the proceedings, Göring tried to dominate the other defendants, and he was eventually placed in solitary confinement when he attempted to influence their testimony.[134] Göring told American psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn that the court was "stupid" to try "little fellows" like Funk and Kaltenbrunner instead of letting Göring take all the blame on himself.[135] He also claimed that he had never heard of most of the other defendants before the trial.[135]

.jpg.webp)

On several occasions over the course of the trial, the prosecution showed films of the concentration camps and other atrocities. Everyone present, including Göring, found the contents of the films shocking; he said that the films must have been faked. Witnesses, including Paul Körner and Erhard Milch, tried to portray Göring as a peaceful moderate. Milch stated that it had been impossible to oppose Hitler or disobey his orders; to do so would likely have meant death for oneself and one's family.[136] When testifying on his own behalf, Göring emphasised his loyalty to Hitler, and claimed to know nothing about what had happened in the concentration camps, which were under Himmler's control. He provided evasive, convoluted answers to direct questions and had plausible excuses for all of his actions during the war. He used the witness stand as a venue to expound at great length on his own role in the Reich, attempting to present himself as a peacemaker and diplomat before the outbreak of the war.[137] During cross-examination, chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson read the minutes of a meeting that had been held shortly after Kristallnacht, a major pogrom in November 1938. At the meeting, Göring had plotted to confiscate Jewish property in the wake of the pogrom.[138] Later, David Maxwell-Fyfe proved that Göring must have known about the killing of 50 airmen who had been recaptured after escaping from Stalag Luft III in time to have saved them.[139] He also presented clear evidence that Göring knew about the extermination of the Hungarian Jews.[140]

Göring was found guilty on all four counts and was sentenced to death by hanging. The judgment stated:

There is nothing to be said in mitigation. For Göring was often, indeed almost always, the moving force, second only to his leader. He was the leading war aggressor, both as political and as military leader; he was the director of the slave labour programme and the creator of the oppressive programme against the Jews and other races, at home and abroad. All of these crimes he has frankly admitted. On some specific cases there may be conflict of testimony, but in terms of the broad outline, his own admissions are more than sufficiently wide to be conclusive of his guilt. His guilt is unique in its enormity. The record discloses no excuses for this man.[141]

Göring made an appeal asking to be shot as a soldier instead of hanged as a common criminal, but the court refused.[142] He committed suicide with a potassium cyanide capsule the night before he was to be hanged.[143]

Speculation as to how Göring obtained the poison holds that US Army lieutenant Jack G. Wheelis, who was stationed at the trials, retrieved the capsules from their hiding place among Göring's confiscated personal effects and passed them to Göring,[144] who had earlier presented Wheelis with his gold watch, pen, and cigarette case.[145] In 2005, former US Army private Herbert Lee Stivers, who served in the 1st Infantry Division's 26th Infantry Regiment—the honour guard for the Nuremberg Trials—claimed he gave Göring "medicine" hidden inside a fountain pen that a German woman had asked him to smuggle into the prison. Stivers later said that he did not know what was in the pill until after Göring's suicide.[146]

Göring's body, as with those of the men who were executed, was displayed at the execution ground for witnesses. The bodies were cremated at Ostfriedhof, Munich, and the ashes were scattered in the Isar River.[147][148][149]

Personal properties

Göring's name is closely associated with the Nazi plunder of Jewish property. His name appears 135 times on the OSS Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) Red Flag Names List[150] compiled by US Army intelligence in 1945-6 and declassified in 1997.[151]

The confiscation of Jewish property gave Göring the opportunity to amass a personal fortune. Some properties he seized himself or acquired for a nominal price. In other cases, he collected bribes for allowing others to steal Jewish property. He took kickbacks from industrialists for favourable decisions as Four Year Plan director, and money for supplying arms to the Spanish Republicans in the Spanish Civil War via Pyrkal in Greece (although Germany was supporting Franco and the Nationalists).[152]

Göring was appointed Reich Master of the Hunt in 1933 and Master of the German Forests in 1934. He instituted reforms to the forestry laws and acted to protect endangered species. Around this time he became interested in Schorfheide Forest, where he set aside 100,000 acres (400 km2) as a state park, which is still extant. There he built an elaborate hunting lodge, Carinhall, in memory of his first wife, Carin. By 1934, her body had been transported to the site and placed in a vault on the estate.[153] Through most of the 1930s, Göring kept pet lion cubs, borrowed from the Berlin Zoo, both at Carinhall and at his house at Obersalzberg.[154] The main lodge at Carinhall had a large art gallery where Göring displayed works that had been plundered from private collections and museums around Europe from 1939 onward.[155][156] Göring worked closely with the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (transl. Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce), an organisation tasked with the looting of artwork and cultural material from Jewish collections, libraries, and museums throughout Europe.[157] Headed by Alfred Rosenberg, the task force set up a collection centre and headquarters in Paris. Some 26,000 railroad cars full of art treasures, furniture, and other looted items were sent to Germany from France alone. Göring repeatedly visited the Paris headquarters to review the incoming stolen goods and to select items to be sent on a special train to Carinhall and his other homes.[158] The estimated value of his collection, which numbered some 1,500 pieces, was $200 million.[159]

.jpg.webp)

Göring was known for his extravagant tastes and garish clothing. He had various special uniforms made for the many posts he held;[160] his Reichsmarschall uniform included a jewel-encrusted baton. Hans-Ulrich Rudel, the top Stuka pilot of the war, recalled twice meeting Göring dressed in outlandish costumes: first, a medieval hunting costume, practicing archery with his doctor; and second, dressed in a red toga fastened with a golden clasp, smoking an unusually large pipe. Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano once noted Göring wearing a fur coat that looked like what "a high grade prostitute wears to the opera."[161] He threw lavish housewarming parties each time a round of construction was completed at Carinhall, and changed costumes several times throughout the evenings.[162]

Göring was noted for his patronage of music, especially opera. He entertained frequently and sumptuously, and hosted elaborate birthday parties for himself.[163] Armaments minister Albert Speer recalled that guests brought expensive gifts such as gold bars, Dutch cigars, and valuable artwork. For his birthday in 1944, Speer gave Göring an oversized marble bust of Hitler.[164] As a member of the Prussian Council of State, Speer was required to donate a considerable portion of his salary towards the council's birthday gift to Göring without even being asked. Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch told Speer that similar donations were required out of the Air Ministry's general fund.[165] For his birthday in 1940, Italian Foreign Minister Count Ciano decorated Göring with the coveted Collar of Annunziata. The award reduced him to tears.[166]

The design of the Reichsmarschall standard, on a light blue field, featured a gold German eagle grasping a wreath surmounted by two batons overlaid with a swastika. The reverse side of the flag had the Großkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes (transl. Grand Cross of the Iron Cross) surrounded by a wreath between four Luftwaffe eagles. The flag was carried by a personal standard-bearer at all public occasions.

Though he liked to be called "der Eiserne" (transl. the Iron Man), the once dashing and muscular fighter pilot had become corpulent. He was one of the few Nazi leaders who did not take offence at hearing jokes about himself, "no matter how rude", taking them as a sign of popularity. Germans joked about his ego, saying that he would wear an admiral's uniform with rubber medals to take a bath, and his obesity, joking that "he sits down on his stomach".[167][168] One joke claimed that he had sent a wire to Hitler after his visit to the Vatican: "Mission accomplished. Pope unfrocked. Tiara and pontifical vestments are a perfect fit."[169]

Role in the Holocaust

Joseph Goebbels and Himmler were far more antisemitic than Göring, who mainly adopted that attitude because party politics required him to do so.[170] His deputy, Erhard Milch, had a Jewish parent. However, Göring supported the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, and later initiated economic measures unfavourable to Jews.[170] He required the registration of all Jewish property as part of the Four Year Plan, and at a meeting held after Kristallnacht was livid that the financial burden for the Jewish losses would have to be made good by German-owned insurance companies. He proposed that the Jews be fined one billion marks.[171]

At the same meeting, options for the disposition of the Jews and their property were discussed. Jews would be segregated into ghettos or encouraged to emigrate, and their property would be seized in a programme of Aryanization. Compensation for seized property would be low, if any was given at all.[171] Detailed minutes of this meeting and other documents were read out at the Nuremberg trial, proving his knowledge of and complicity with the persecution of the Jews.[138]

On 24 January 1939, Göring established in Berlin the head office of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration,[172] modelled on the similar organization established in Vienna in August 1938.[173] Under the direction of Heydrich, it was tasked with using any means necessary to prompt Jews to leave the Reich, and creating a Jewish organization that would co-ordinate emigration from the Jewish side.[174]

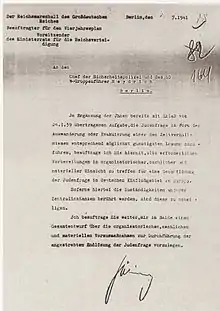

In July 1941, Göring issued a memo to Heydrich ordering him to organise the practical details of the Final Solution to the "Jewish Question". By the time that this letter was written, many Jews and others had already been killed in Poland, Russia, and elsewhere. At the Wannsee Conference, held six months later, Heydrich formally announced that genocide of the Jews was now official Reich policy. Göring did not attend the conference, but he was present at other meetings where the number of people killed was discussed.[175][176]

Göring directed anti-partisan operations by Luftwaffe security battalions in the Białowieża Forest between 1942 and 1944 that resulted in the murder of thousands of Jews and Polish civilians.[177]

At the Nuremberg trial Göring told first lieutenant and U.S. Army psychologist Gustave Gilbert that he would never have supported the anti-Jewish measures if he had known what was going to happen. "I only thought we would eliminate Jews from positions in big business and government", he claimed.[178][179]

Decorations and awards

German

- Iron Cross

- Pour le Mérite (2 June 1918)[180]

- Blood Order (Commemorative Medal of 9 November 1923)[180]

- Clasp to the Iron Cross

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 30 September 1939[180]

- Grand Cross of the Iron Cross for "the victories of the Luftwaffe in 1940 during the French campaign" (the only award of this decoration during World War II – 19 August 1940)[181]

- Order from the Grand Duke of Baden Orden vom Zähringer Löwen (de) Knights Cross 2nd Class with Swords[181]

- Golden Party Badge[180]

- Knights Cross with Swords of the House Order of Hohenzollern[181]

- Knights Cross of the Military Karl-Friedrich Merit Order[181]

- Danzig Cross, 1st and 2nd class[180]

Foreign

- Knight of the Order of Saints Cyril and Methodius (Kingdom of Bulgaria)[182]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog, with Breast Star in Diamonds (Kingdom of Denmark) (25 July 1938)[183][184]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Rose of Finland (6 March 1935)[185]

- Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the White Rose of Finland (21 April 1941)[186]

- Grand Cross with Swords of the Order of the Cross of Liberty (Finland) (25 March 1942)[187]

- Grand Cross of the Order of St Stephen (Kingdom of Hungary)[188]

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (Kingdom of Italy) (12 January 1940)[189]

- Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, with Collar (Kingdom of Sweden) (1939)[190]

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun, with Paulownia Flowers (Empire of Japan) (4 October 1943)[191]

See also

- Aerial victory standards of World War I

- Air warfare of World War II

- Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1 Hermann Göring

- Glossary of Nazi Germany

- Glossary of German military terms

- Göring's Green Folder

- List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

Notes

- Göring is the German spelling, but the name is commonly transliterated Goering in English and other languages, using ⟨oe⟩ the alternative German spelling for umlauts in general.

- The swastika was a badge which the count and some friends had adopted at school, and he adopted it as a family emblem. See Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 403–404.

Citations

- Kershaw 2008, p. 284.

- Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression 1946, pp. 100–101.

- Evans 2005, p. 358.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 21.

- Block & Trow 1971, pp. 327–330.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 21–22.

- Freitag 2015, pp. 25–45.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 22–24.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 24–25.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 24–28.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 28–29.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 31–32.

- Franks 1993, pp. 95, 117, 156.

- Franks 1993, p. 117.

- Kilduff 2013, pp. 165–166.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 31–33.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 403.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 34–36.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 39.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 39–41.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 43.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 41, 43.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 45, 47.

- Miller 2006, p. 426.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 112.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 47.

- Hitler 1988, p. 168.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 49–51.

- Holland 2011, p. 54.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 131.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 57–58.

- Speer 1971, p. 644.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 59–60.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 61.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 404.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 62, 64.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 160.

- Shirer 1960, p. 146.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 118–121.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 66.

- Reichstag databank.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 136, 138.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 74.

- Evans 2003, p. 297.

- Evans 2003, pp. 329–330.

- Shirer 1960, p. 194.

- Evans 2003, p. 331.

- Shirer 1960, p. 192.

- Bullock 1999, p. 262.

- Shirer 1960, p. 193.

- Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, 18 March 1946.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 111.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 139–140.

- Gunther 1940, p. 63.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 187.

- Miller & Schulz 2015, p. 47.

- Miller & Schulz 2015, pp. 50–51.

- Frank 1933–1934, p. 253.

- Evans 2005, p. 54.

- Goldhagen 1996, p. 95.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 306.

- Evans 2005, pp. 31–35, 39.

- Evans 2005, pp. 38.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 116–117.

- Evans 2005, p. 364.

- Evans 2005, pp. 357–360.

- Shirer 1960, p. 311.

- Evans 2005, p. 361.

- Overy 2002, p. 145.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 116.

- Gerwarth 2011, pp. 116, 117.

- Evans 2005, pp. 642–644.

- Evans 2005, pp. 646–652.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 194–197.

- Evans 2005, p. 674.

- Noakes & Pridham 2001, p. 119.

- Gunther 1940, p. 19.

- Overy 2002, p. 73.

- Overy 2002, p. 236.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 197, 211.

- Broszat 1981, pp. 308–309.

- Shirer 1960, p. 597.

- Shirer 1960, p. 599.

- Hooton 1999, pp. 177–189.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 721, 723, 725.

- Fellgiebel 2000, p. 198.

- Shirer 1960, p. 615.

- Evans 2008, pp. 113, 136, 143.

- Oestermann 2001, p. 157.

- Selwood 2015.

- Raeder 2001, pp. 324–325.

- Bungay 2000, p. 337.

- Evans 2008, p. 144.

- Taylor 1965, p. 500.

- Evans 2008, p. 145.

- Evans 2008, pp. 178–179.

- Evans 2008, p. 187.

- Evans 2008, p. 201.

- Stolfi 1982.

- Evans 2008, pp. 207–213.

- Fleming 1987.

- Evans 2008, pp. 404–405.

- Evans 2008, p. 421.

- Evans 2008, p. 409.

- Evans 2008, pp. 412–413.

- Speer 1971, p. 329.

- Shirer 1960, p. 932.

- Evans 2008, pp. 438, 441.

- Speer 1971, p. 378.

- Evans 2008, p. 461.

- Evans 2008, p. 447.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 296, 297, 299.

- Evans 2008, p. 510.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 295, 302.

- Evans 2008, p. 725.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 310.

- Evans 2008, p. 722.

- Evans 2008, p. 723.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 1115–1116.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1116.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 315.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1118.

- Speer 1971, pp. 608–609.

- Evans 2008, p. 724.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 318.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1126.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 320–325.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1128.

- Gilbert 1995, p. 31.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 329–331.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 336–337.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 337.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 339.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 341–342.

- Goldensohn 2004.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 343–347.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 359–367.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 369.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 371.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 374–375.

- International Military Tribunal 1946.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 392–393.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 964.

- Taylor 1992, p. 623.

- Botting 2006, p. 280.

- BBC News 2005.

- Darnstädt 2005.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 393.

- Overy 2001, p. 205.

- OSS Reports.

- NARA Records.

- Beevor 2006, pp. 366–368, 538.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 120–123.

- Kellerhoff 2018.

- Speer 1971, pp. 244–245.

- Rothfeld 2002.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 283–285.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 283–285, 291.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 281.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 115–116.

- Fussell 2002, pp. 24–25.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 122.

- Speer 1971, p. 417.

- Speer 1971, pp. 416–417.

- Speer 1971, pp. 417–418.

- Mosley 1974, p. 280.

- Block & Trow 1971, p. 330.

- Gunther 1940, p. 65.

- Evans 2005, p. 409.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 136–137.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 189–191.

- Hilberg 1985, p. 160.

- Cesarani 2005, p. 62.

- Cesarani 2005, p. 77.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, pp. 259–260.

- Blood 2001, p. 75.

- Blood 2010, pp. 261–262, 266.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 378.

- Gilbert 1995, p. 208.

- Miller 2006, p. 442.

- Miller & Schulz 2015, p. 89.

- Petrov 2005, p. 56.

- Gade 2011.

- Bille-Hansen & Holck 1943, p. 20.

- Matikkala 2017, p. 36.

- Matikkala 2017, p. 515.

- Matikkala 2017, p. 511.

- Lajos 2011, p. 41.

- Overy 2000, p. 233.

- Statskalender 1940, p. 10.

- "Odznaczenie japońskie dla marsz. Goeringa" (PDF), Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish) (233): 1, 5 October 1943, retrieved 20 January 2021

Sources

- "Kungl. Svenska Riddarordnarna". Bihang till Sveriges Statskalender 1940 (in Swedish). Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri. 1940.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2165-7.

- Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1943). Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1943 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1943] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. Retrieved 20 January 2021 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- Block, Maxine; Trow, E. Mary (1971). Current Biography: Who's News and Why 1941. New York: H.W. Wilson. OCLC 16655369.

- Blood, Philip W. (2001). Holmes, E. R. (ed.). Bandenbekämpfung: Nazi occupation security in Eastern Europe and Soviet Russia 1942–45 (PhD thesis). Cranfield University.

- Blood, Philip W. (3 August 2010). "Securing Hitler's Lebensraum: The Luftwaffe and Bialowieza Forest, 1942–1944". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 24 (2): 247–272. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcq024.

- Botting, Douglas (2006). In the Ruins of The Reich: Germany 1945–1949. London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-413-77511-5.

- Broszat, Martin (1981). The Hitler State: The Foundation and Development of the Internal Structure of the Third Reich. New York: Longman Inc. ISBN 0-582-49200-9.

- Bullock, Alan (1999) [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-036-0.

- "Art Provenance and Claims Records and Research". National Archives and Records Administration. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Bungay, Stephen (2000). The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-85410-721-3.

- Cesarani, David (2005) [2004]. Eichmann: His Life and Crimes. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-944844-0.

- Darnstädt, Thomas (4 April 2005). "Ein Glücksfall der Geschichte". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Datenbank der deutschen Parlamentsabgeordneten. Basis: Parlamentsalmanache/Reichstagshandbücher 1867 – 1938". www.reichstag-abgeordnetendatenbank.de. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes, 1939–1945 (in German). Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Fleming, Thomas (December 1987). "The Big Leak". American Heritage. 38 (8). Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Frank, Hans, ed. (1933–1934). Jahrbuch der Akademie für Deutsches Recht [Yearbook of the Academy for German Law] (1st ed.). München/Berlin/Leipzig: Schweitzer Verlag.

- Franks, Norman (1993). Above the Lines: The Aces and Fighter Units of the German Air Service, Naval Air Service and Flanders Marine Corps, 1914–1918. Oxford: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-19-9.

- Freitag, Christian H. (2015). Ritter, Reichsmarschall & Revoluzzer. Aus der Geschichte eines Berliner Landhauses (in German). Berlin: Friedenauer Brücke. ISBN 978-3-9816130-2-5.

- Fussell, Paul (2002). Uniforms: Why We Are What We Wear. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-38188-3.

- Gade, Ida K. Richter (21 February 2011). "Herman Göring". berlingske.dk (in Danish). Berlingske Media A/S. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

- Gilbert, Gustave (1995). Nuremberg Diary. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80661-2.

- Goldensohn, Leon N. (2004). The Nuremberg Interviews: Conversations with the Defendants and Witnesses. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41469-5.

- Goldhagen, Daniel (1996). Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-44695-8.

- "Guard 'gave Goering suicide pill'". BBC News. 8 February 2005. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 836676034.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 0-8419-0910-5.

- Hitler, Adolf (1988). Hitler's Table Talk, 1941–1944. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285180-2.

- Holland, James (2011). The Battle of Britain: Five Months That Changed History; May-October 1940. Manhattan, New York City: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-31-267500-4.

- Hooton, Edward (1999). Phoenix Triumphant: The Rise and Rise of the Luftwaffe. Garden City: Arms & Armour. ISBN 1-85409-181-6.

- "Judgment of International Military Tribunal on Hermann Goering". The Avalon Project. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 30 September 1946. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (23 March 2018). "Raubkunst: Für Löwen hatte Hermann Göring eine Schwäche". Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Kilduff, Peter (2013). Herman Göring, Fighter Ace: The World War I Career of Germany's Most Infamous Airman. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-906502-66-9.

- Lajos, Pallos (2011). "A Magyar Királyi Szent István Rend jelvényei a Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum Éremtárában". In Tibor, Kovács (ed.). 2010-2011 A Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum történeti évkönyve. Folia Historica: Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum Évkönyve (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian National Museum. pp. 39–65. ISSN 0133-6622.

- Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (2011) [1962]. Goering: The Rise and Fall of the Notorious Nazi Leader. London: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-61608-109-6.

- Matikkala, Antti (2017). Kunnian ruletti: Korkeimmat ulkomaalaisille 1941-1944 annetut suomalaiset kunniamerkit (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-952-222-847-5.

- Miller, Michael D. (2006). Leaders of the SS and German Police, Vol. 1. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender. ISBN 978-93-297-0037-2.

- Miller, Michael D.; Schulz, Andreas (2015). Leaders of the Storm Troops, Vol. 1. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-87-1.

- Mosley, Leonard (1974). The Reich Marshal: A Biography of Hermann Goering. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04961-7.

- "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume 2, Chapter XV, Part 3: The Reich Cabinet" (PDF). Office of United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality. 1946. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Noakes, Jeremy; Pridham, Geoffrey, eds. (2001) [1988]. Nazism 1919–1945: Foreign Policy, War and Racial Extermination. Exeter Studies in History. Vol. 3. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

- "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings, Volume 9: Eighty-fourth day, Monday, 18 March 1946, morning session". The Avalon Project. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Oestermann, Günter (2001). Junger Wolf im Nebel. Ein Junge in Deutschland 1930–1945 (in German). Hamburg: [Norderstedt] Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-8311-2487-9.

- "OSS (USS Office of Strategic Services) Art Looting Intelligence Unit (ALIU) Reports 1945–1946 and ALIU Red Flag Names List and Index". Central Registry of Information on Looted Cultural Property 1933–1945. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Overy, Richard (2000). Goering: Hitler's Iron Knight. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-048-4.

- Overy, Richard J. (2001). Interrogations: The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands, 1945. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03008-8.

- Overy, Richard J. (2002) [1994]. War and Economy in the Third Reich. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-164737-6.

- Petrov, Todor (2005). Bulgarian Orders and Medals 1878–2005. Sofia: Military Publishing House Ltd. ISBN 954-509-317-X.

- Raeder, Erich (2001). Erich Rader, Grand Admiral: The Personal Memoir of the Commander in Chief of the German Navy From 1935 Until His Final Break With Hitler in 1943. London: New York: Da Capo Press. United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-306-80962-1.

- Rothfeld, Anne (2002). "Nazi Looted Art: The Holocaust Records Preservation Project, Part 1". Prologue Magazine. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 34 (3).

- Selwood, Dominic (13 February 2015). "Dresden was a civilian town with no military significance. Why did we burn its people?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- Speer, Albert (1971) [1969]. Inside the Third Reich. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-00071-5.

- Stolfi, Russel (March 1982). "Barbarossa Revisited: A Critical Reappraisal of the Opening Stages of the Russo-German Campaign (June–December 1941)" (PDF). Journal of Modern History. 54 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1086/244076. S2CID 143690841.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1965). English History 1914–1945. Reading, Berkshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280140-6.

- Taylor, Telford (1992). The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-58355-6.

Further reading

- Brandenburg, Erich (1995). Die Nachkommen Karls Des Grossen. Neustadt/Aisch: Degener. ISBN 3-7686-5102-9.

- Burke, William Hastings (2009). Thirty Four. London: Wolfgeist. ISBN 978-0-9563712-0-1.

- Butler, Ewan (1951). Marshal Without Glory. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 1246848.

- Fest, Joachim (2004). Inside Hitler's Bunker. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-13577-0.

- Frischauer, Willi (2013) [1950]. Goering. Unmaterial Books. ISBN 978-1-78301-221-3.

- Göring, Hermann (1934). Germany Reborn. London: E. Mathews & Marrot. OCLC 570220. Archived from the original on 3 August 2004.

- Leffland, Ella (1990). The Knight, Death and the Devil. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-05836-1.

- Maser, Werner (2000). Hitlers janusköpfiger Paladin: die politische Biographie (in German). Berlin. ISBN 3-86124-509-4.

- Maser, Werner (2004). Fälschung, Dichtung und Wahrheit über Hitler und Stalin (in German). Munich: Olzog. ISBN 3-7892-8134-4.

- Paul, Wolfgang (1983). Wer War Hermann Göring: Biographie (in German). Esslingen: Bechtle. ISBN 3-7628-0427-3.

External links

- Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 9 Transcript of Goering's testimony at the trial

- "Lost Prison Interview with Hermann Goring: The Reichsmarschall's Revelations" published by World War II Magazine

- Göring at Långbro asylum

- The Goering Collection: online database (in German as Die Kunstsammlung Hermann Göring) of 4263 artworks in Hermann Göring's collection

- Newspaper clippings about Hermann Göring in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg.webp)