Moroccan architecture

Moroccan architecture refers to the architecture characteristic of Morocco throughout its history and up to modern times. The country's diverse geography and long history, marked by successive waves of settlers through both migration and military conquest, are all reflected in its architecture. This architectural heritage ranges from ancient Roman and Berber (Amazigh) sites to 20th-century colonial and modern architecture.

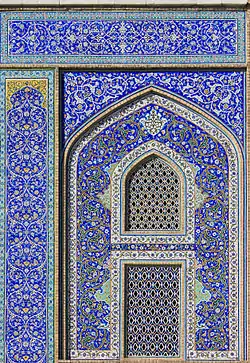

The most recognizably "Moroccan" architecture, however, is the traditional architecture that developed in the Islamic period (7th century and after) which dominates much of Morocco's documented history and its existing heritage.[1][2] This "Islamic architecture" of Morocco was part of a wider cultural and artistic complex, often referred to as "Moorish" art, which characterized Morocco, al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal), and parts of Algeria and even Tunisia.[3][2][4][5] It blended influences from Berber culture in North Africa, pre-Islamic Spain (Roman, Byzantine, and Visigothic), and contemporary artistic currents in the Islamic Middle East to elaborate a unique style over centuries with recognizable features such as the "Moorish" arch, riad gardens (courtyard gardens with a symmetrical four-part division), and elaborate geometric and arabesque motifs in wood, stucco, and tilework (notably zellij).[3][2][6][7]

.jpg.webp)

Although Moroccan Berber architecture is not strictly separate from the rest of Moroccan architecture, many structures and architectural styles are distinctively associated with traditionally Berber or Berber-dominated regions of Morocco such as the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara and pre-Sahara regions.[8] These mostly rural regions are marked by numerous kasbahs (fortresses) and ksour (fortified villages) shaped by local geography and social structures, of which one of the most famous is Ait Benhaddou.[9] They are typically made of rammed earth and decorated with local geometric motifs. Far from being isolated from other historical artistic currents around them, the Berbers of Morocco (and across North Africa) adapted the forms and ideas of Islamic architecture to their own conditions and in turn contributed to the formation of Western Islamic art, particularly during their political domination of the region over the centuries of Almoravid, Almohad, and Marinid rule.[7][8]

.jpg.webp)

Modern architecture in Morocco includes many examples of early 20th-century Art Deco and local neo-Moorish (or Mauresque) architecture constructed during the French (and Spanish) colonial occupation of the country between 1912 and 1956 (or until 1958 for Spain).[10][11] In the later 20th century, after Morocco regained its independence, some new buildings continued to pay tribute to traditional Moroccan architecture and motifs (even when designed by foreign architects), as exemplified by the Mausoleum of King Mohammed V (completed in 1971) and the massive Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca (completed in 1993).[12] Modernist architecture is also evident in contemporary constructions, not only for regular everyday structures but also in major prestige projects.[13][14]

History

Antiquity

Although less well-documented, Morocco's earliest historical periods were dominated by Berber groups and kingdoms, up to the Berber kingdom of Mauretania.[15] In the 7th or 8th century BC the Phoenicians founded a colony of Lixus on the Atlantic coast, which later came under Carthaginian, Mauretanian, and eventually Roman control.[16][17] Other important towns such as Tingis (present-day Tangier) and Sala (Chellah) were founded and developed by Phoenicians or Mauretanian Berbers.[1]: 69 The settlement of Volubilis was the traditional capital of the Mauretanian kingdom from the second century BC onward, though it may have been founded as early as the third century BC.[18] Under Mauretanian rule its streets were laid out in a grid plan and may have included a palace complex and fortified walls.[18][15]: 32 The influence of Punic (Carthaginian) culture in the city is archaeologically attested by Punic stelae and the remains of a Punic temple.[18] The Mauretanian king Juba II (r. 25 BC–23 AD), a client king of Rome and a promoter of late Hellenistic culture, built a palace in Lixus that was based on Hellenistic models.[15]: 43–44 [17]

Roman settlement and construction was much less extensive in the territory of present-day Morocco, which was on the edge of the empire, than it was in nearby regions like Hispania or Africa (present-day Tunisia). The most significant cities, and the ones most directly influenced by Roman culture, were Tingis, Volubilis, and Sala.[1]: 67–68 Large-scale Roman architecture was relatively rare; for example, there is only one known amphitheater in the region, at Lixus.[1]: 68 Volubilis, the most inland major city, became a well-developed provincial Roman municipium and its ruins today are the best-preserved Roman site in Morocco. It included aqueducts, a forum, bath complexes, a basilica, the Capitoline Temple, and a triumphal arch dedicated to the emperor Caracalla and his mother in 216–217. The site has also preserved a number of fine Roman mosaics.[18][19] It continued to be an urban center even after the end of Roman occupation in 285, with evidence of Latin Christian, Berber, and Byzantine (Eastern Roman) occupation.[20]: 53

Early Islamic period (8th–10th century)

In the early 8th century the region became steadily integrated into the emerging Muslim world, beginning with the military incursions of Musa ibn Nusayr and becoming more definitive with the advent of the Idrisid dynasty at the end of that century.[21] The arrival of Islam was extremely significant as it developed a new set of societal norms (although some of them were familiar to Judeo-Christian societies) and institutions which therefore shaped, to some extent, the types of buildings being built and the aesthetic or spiritual values that guided their design.[22][23][24][25]

The Idrisids founded the city of Fes, which became their capital and the major political and cultural center of early Islamic Morocco.[1][26] In this early period Morocco also absorbed waves of immigrants from Tunisia and al-Andalus (Muslim-ruled Spain and Portugal), who brought in cultural and artistic influences from their home countries.[21][4] The earliest well-known Islamic-era monuments in Morocco, such as the al-Qarawiyyin and Andalusiyyin mosques in Fes, were built in the hypostyle form and made early use of the horseshoe or "Moorish" arch.[3][27] These reflected early influences from major monuments like the Great Mosque of Kairouan and the Great Mosque of Cordoba.[7] In the 10th century much of northern Morocco came directly within the sphere of influence of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba, with competition from the Fatimid Caliphate further east.[21] Early contributions to Moroccan architecture from this period include expansions to the Qarawiyyin and Andalusiyyin mosques and the addition of their square-shafted minarets, the oldest surviving mosques in Morocco, which anticipate the standard form of later Moroccan minarets.[27][3][28]: 126

The Berber Empires: Almoravids and Almohads (11th–13th centuries)

.jpg.webp)

The collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in the early 11th century was followed by the significant advance of Christian kingdoms into Muslim al-Andalus and the rise of major Berber empires in Morocco. The latter included first the Almoravids (11th-12th centuries) and then the Almohads (12th-13th centuries), both of whom also took control of remaining Muslim territory in al-Andalus, creating empires that stretched across large parts of western and northern Africa and into Europe.[7] This period is considered one of the most formative stages of Moroccan and Moorish architecture, establishing many of the forms and motifs that were refined in subsequent centuries.[3][29][7][30] These two empires were responsible for establishing a new imperial capital at Marrakesh and the Almohads also began construction of a monumental capital in Rabat.

The Almoravids adopted the architectural developments of al-Andalus, such as the complex interlacing arches of the Great Mosque in Cordoba and of the Aljaferia palace in Zaragoza, while also introducing new ornamental techniques from the east such as muqarnas ("stalactite" or "honeycomb" carvings).[29][31] The Almohad Kutubiyya and Tinmal mosques are often considered the prototypes of later Moroccan mosques.[29][3] The monumental minarets (e.g. the Kutubiyya minaret, the Giralda of Seville, and the Hassan Tower of Rabat) and ornamental gateways (e.g. Bab Agnaou in Marrakesh, and Bab Oudaia and Bab er-Rouah in Rabat) of the Almohad period also established the overall decorative schemes that became recurrent in these architectural elements thenceforth. The minaret of the Kasbah Mosque of Marrakesh was particularly influential and set a style that was repeated, with minor elaborations, in the following Marinid period.[32][29][3] The Almoravids and Almohads also promoted the tradition of establishing garden estates in the countryside of their capital, such as the Menara Garden and the Agdal Gardens on the outskirts of Marrakesh. In the late 12th century the Almohads created a new fortified palace district, the Kasbah of Marrakesh, to serve as their royal residence and administrative center. These traditions and policies had earlier precedents in al-Andalus – such as the creation of Madinat al-Zahra near Cordoba – and were subsequently repeated by future rulers of Morocco.[32][7][3][33]

The Marinids (13th–15th centuries)

.jpg.webp)

The Berber Marinid dynasty that followed was also important in further refining the artistic legacy established by their predecessors. Based in Fes, they built monuments with increasingly intricate and extensive decoration, particularly in wood and stucco.[3] They were also the first to deploy extensive use of zellij (mosaic tilework in complex geometric patterns).[2] Notably, they were the first to build madrasas, a type of institution which originated in Iran and had spread west.[3] The madrasas of Fes, such as the Bou Inania, al-Attarine, and as-Sahrij madrasas, as well as the Marinid madrasa of Salé and the other Bou Inania in Meknes, are considered among the greatest architectural works of this period.[34][5][3] While mosque architecture largely followed the Almohad model, one noted change was the progressive increase in the size of the sahn or courtyard, which was previously a minor element of the floor plan but which eventually, in the subsequent Saadian period, became as large as the main prayer hall, and sometimes larger.[35] Like the Almohads before them, the Marinids created a separate palace-city for themselves; this time, outside Fes. Later known as Fes Jdid, this new fortified citadel had a set of double walls for defense, a new Grand Mosque, a vast royal garden to the north known as el-Mosara, residences for government officials, and barracks for military garrisons.[33][36] Later on, probably in the 15th century, a new Jewish quarter was created on its south side, the first mellah in Morocco, prefiguring the creation of similar districts in other Moroccan cities in later periods.[37][38]

The architectural style under the Marinids was very closely related to that found in the Emirate of Granada, in Spain, under the contemporary Nasrid dynasty.[3] The decoration of the famous Alhambra is thus reminiscent of what was built in Fes at the same time. When Granada was conquered in 1492 by Catholic Spain and the last Muslim realm of al-Andalus came to an end, many of the remaining Spanish Muslims (and Jews) fled to Morocco and North Africa, further increasing the Andalusian influence in these regions in subsequent generations.[5]

The Sharifian dynasties: Saadians and Alaouites (16th–19th centuries)

After the Marinids came the Saadian dynasty, which marked a political shift from Berber-led empires to sultanates led by Arab sharifian dynasties. Artistically and architecturally, however, there was broad continuity and the Saadians are seen by modern scholars as continuing to refine the existing Moroccan-Moorish style, with some considering the Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh as one of the apogees of this style.[35]

Starting with the Saadians, and continuing with the Alaouites (their successors and the reigning monarchy today), Moroccan art and architecture is portrayed by modern (Western) scholars as having remained essentially "conservative"; meaning that it continued to reproduce the existing style with high fidelity but did not introduce major new innovations.[3][32][35][33][2] The Saadians, especially under the sultans Abdallah al-Ghalib and Ahmad al-Mansur, were extensive builders and benefitted from great economic resources at the height of their power in the late 16th century. In addition to the Saadian Tombs, they also built the Ben Youssef Madrasa and several major mosques in Marrakesh including the Mouassine Mosque and the Bab Doukkala Mosque. These two mosques are notable for being part of larger multi-purpose charitable complexes including several other structures like public fountains, hammams, madrasas, and libraries. This marked a shift from the previous patterns of architectural patronage and may have been influenced by the tradition of building such complexes in Mamluk architecture in Egypt and the külliyes of Ottoman architecture.[32][29] The Saadians also rebuilt the royal palace complex in the Kasbah of Marrakesh for themselves, where Ahmad al-Mansur constructed the famous El Badi Palace (built between 1578 and 1593) which was known for its superlative decoration and costly building materials including Italian marble.[32][29]

The Alaouites, starting with Moulay Rashid in the mid-17th century, succeeded the Saadians as rulers of Morocco and continue to be the reigning monarchy of the country to this day. As a result, many of the mosques and palaces standing in Morocco today have been built or restored by the Alaouites at some point or another.[5][32][26] Ornate architectural elements from Saadian buildings, most famously from their lavish El Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il (1672–1727).[35] Moulay Isma'il is also notable for having built a vast imperial palace complex – similar to previous palace-citadels but on a grander scale than before – in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today.[39][33] In his time Tangier was also returned to Moroccan control in 1684, and much of the city's current Moroccan and Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after.[40][5]

n 1765 Sultan Mohammed Ben Abdallah (one of Moulay Isma'il's sons) started the construction of a new port city called Essaouira (formerly Mogador), located along the Atlantic coast as close as possible to his capital at Marrakesh, to which he tried to move and restrict European trade.[33]: 264 He hired European architects to design the city, resulting in a relatively unique Moroccan-built city with Western European architecture, particularly in the style of its fortifications. Similar coastal fortifications or bastions, usually known as a sqala, were built at the same time in other port cities like Anfa (present-day Casablanca), Rabat, Larache, and Tangier.[3]: 409 Up until the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Alaouite sultans and their ministers continued to build beautiful palaces, many of which are now used as museums or tourist attractions, such as the Bahia Palace in Marrakesh, the Dar Jamaï in Meknes, and the Dar Batha in Fes.[2][11]

Modern and contemporary architecture: 20th century to present day

In the 20th century, Moroccan architecture and cities were also shaped by the period of French colonial control (1912–1956) as well as Spanish colonial rule in the north of the country (1912–1958). This era introduced new architectural styles such as Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and other modernist styles, in addition to European ideas about urban planning imposed by colonial authorities.[41] The European architects and planners also drew on traditional Moroccan architecture to develop a style sometimes referred to as Neo-Mauresque (a type of Neo-Moorish style), blending contemporary European architecture with a "pastiche" of traditional Moroccan architecture.[11][10] The French moved the capital to Rabat and founded a number of Villes Nouvelles ("New Cities") next to the historic medinas (old walled cities) to act as new administrative centers, which have since grown beyond the old cities. In particular, Casablanca was developed into a major port and quickly became the country's most populous urban centre.[21] As a result, the city's architecture became a major showcase of Art Deco and colonial Mauresque architecture. Notable examples include the civic buildings of Muhammad V Square (Place Mohammed V), the Cathedral of Sacré-Coeur, the Art Deco-style Cinéma Rialto, the Neo-Moorish-style Mahkamat al-Pasha in the Habous district.[11][42][43][44] Similar architecture also appeared in other major cities like Rabat and Tangier, with examples such as the Gran Teatro Cervantes in Tangier and the Bank al-Maghrib and post office buildings in downtown Rabat.[45][46][47] Elsewhere, the smaller southern town of Sidi Ifni is also notable for Art Deco architecture dating from the Spanish occupation.[48]

Elie Azagury became the first Moroccan modernist architect in the 1950s.[49][50] In the later 20th century and into the 21st century, contemporary Moroccan architecture also continued to pay tribute to the country's traditional architecture. In some cases, international architects were recruited to design Moroccan-style buildings for major royal projects such as the Mausoleum of Mohammed V in Rabat and the massive Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca.[51][12] The monumental new gates of the Royal Palace in Fez, built in 1969–1971, also made use of traditional Moroccan craftsmanship.[2] The new train stations of Marrakesh and Fes are examples of traditional Moroccan forms being adapted to modern architecture.[52] Modernist architecture has also continued to be used, exemplified by buildings like the Sunna Mosque (1966) and the Twin Center (1999) in Casablanca. More recently, some 21st-century examples of major or prestigious architecture projects include the extension of Marrakesh's Menara Airport (completed in 2008),[53] the National Library of Morocco in Rabat (2008), the award-winning High-Speed Train Station in Kenitra (opened in 2018),[54][55] the Finance City Tower in Casablanca (completed in 2019 and one of the tallest buildings in Morocco),[56] and the new Grand Theatre of Rabat by Zaha Hadid (due to be completed in late 2019).[57][58]

Influences

Roman and pre-Islamic

As with the rest of the Mediterranean world, the culture and monuments of Classical Antiquity and of Late Antiquity had an important influence on the architecture of the Islamic world that came after them. In Morocco, the former Roman city of Volubilis acted as the first Idrisid capital before the foundation of Fes.[26][1] The columns and capitals of Roman and early Christian monuments were frequently re-used as spolia in the early mosques of the region – although this was far less common in Morocco, where Roman remains were far sparser.[33]: 43 Later Islamic capitals developed from these models in turn.[3][59] In other examples, the vegetal and floral motifs of Late Antiquity formed one of the bases from which Islamic-era arabesque motifs were derived.[60][3] The iconic horseshoe arch or "moorish" arch, which became a regular feature of Moroccan and Moorish architecture, also had some precedents in Byzantine and Visigothic buildings.[3]: 163–164 [6] Lastly, another major legacy of Greco-Roman heritage was the continuation and proliferation of public bathhouses, known as hammams, across the Islamic world – including Morocco – which were closely based on Roman thermae and took on added social roles.[3][61][62]

Islamic-era Middle East

The arrival of Islam with Arab conquerors from the east in the early 8th century brought about social changes which also required the introduction of new building types such as mosques. The latter followed more or less the model of other hypostyle mosques which were common across much of the Islamic world at the time.[7][33] The traditions of Islamic art also introduced certain aesthetic values, most notably a general preference for avoiding figurative images due to a religious taboo on icons or worshipped images.[63][64] This aniconism in Islamic culture caused artists to explore non-figural art, and created a general aesthetic shift toward mathematically-based decoration, such as geometric patterns, as well as other relatively abstract motifs like arabesques.[65] While figurative images did continue to appear in Islamic art, by the 14th century these were generally absent in the architecture of the western regions of the Islamic world like Morocco.[60] Some figural images of animals still appeared occasionally in royal palaces, such as the sculptures of lions and leopards in the monumental fountain of a former Saadian palace in the Agdal Gardens.[66][67]

Aside from the initial changes brought about by the arrival of Islam, Moroccan culture and architecture continued afterwards to adopt certain ideas and imports from the eastern parts of the Islamic world. These include some of the institutions and building types that became characteristic of the historic Muslim world. For example, bimaristans, historical equivalents of hospitals, first originated further east in Iraq, with the first one being built by Harun al-Rashid (between 786 and 809).[68] They spread westward and first appeared in Morocco around the late 12th century when the Almohads founded a maristan in Marrakesh.[69][70] Madrasas, another important institution, first originated in Iran in the early 11th century under Nizam al-Mulk, and were progressively adopted further west.[3][71][72] The first madrasa in Morocco (Madrasat as-Saffarin) was built in Fes by the Marinids in 1271, and madrasas further proliferated in the 14th century.[3][73] In terms of decorative motifs, muqarnas, a notable feature of Moroccan architecture introduced in the Almoravid period in the 12th century,[3]: 237 also originated at first in Iran before spreading to the west.[29][31]

Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal)

The culture of Muslim-controlled Al-Andalus, which existed across much of the Iberian Peninsula to the north between 711 and 1492, also had close influence on Moroccan history and architecture in a number of ways – and was in turn influenced by Moroccan cultural and political movements. Jonathan Bloom, in his overview of western Islamic architecture, remarks that he "treats the architecture of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula together because the Straits of Gibraltar were less of a barrier and more of a bridge."[33]: 13

In addition to the geographic proximity of the two regions, there were many waves of immigration from Al-Andalus to Morocco of both Muslims and Jews. One of the earliest waves were the Arab exiles from Cordoba who came to Fes after a failed rebellion in the early 9th century.[74]: 44 This population transfer culminated in the waves of refugees that came after the fall of Granada in 1492, including many former elites and members of the Andalusi educated classes.[5] These immigrants played important roles in Moroccan society. Among other examples, it was the early Arab exiles from Cordoba who gave the Andalusiyyin quarter of Fes its name[26] and it was Andalusi refugees in the 16th century who rebuilt and expanded the northern city of Tétouan.[5]

The period of the Umayyad Emirate and Caliphate in Cordoba, which marked the peak of Muslim power in Al-Andalus, was an especially crucial era which saw the construction of some of the region's most important early Islamic monuments. The Great Mosque of Cordoba is frequently cited by scholars as a major influence on the subsequent architecture of the western regions of the Islamic world due to both its architectural innovations and its symbolic importance as the religious heart of the powerful Cordoban Caliphate.[75][6][76][7]: 281–284 Many of its features, such as the ornamental ribbed domes,[3]: 149–151 the minbar, and the polygonal mihrab chamber, would go on to be recurring models of later elements in the Islamic architecture of the wider region.[7]: 284 Likewise, the decorative layout of the Bab al-Wuzara' gateway, the original western gate of the mosque, demonstrates many of the standard elements that recur in the gateways and mihrabs of subsequent periods: namely, a horseshoe arch with decorated voussoirs, a rectangular alfiz frame, and an inscription band.[3]: 165–170 Georges Marçais (an important 20th-century scholar on this subject[77]: 279 ) also traces the origins of some later architectural features directly to the complex arches of Al-Hakam II's 10th-century expansion of the mosque, namely the polylobed arches found throughout the region after the 10th century and the sebka motif which became ubiquitous in Moroccan architecture after the Almohad period (12th-13th centuries).[3] Moreover, for much of the 10th century the Caliphate of Cordoba held northern Morocco in its sphere of influence. During this period Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III contributed to the architecture of Fes by sponsoring the expansion of the Qarawiyyin Mosque.[33] The same caliph also oversaw the construction of the first minaret of Cordoba's mosque, whose shape – a square-based shaft with a secondary lantern tower above it – some scholars see as precursor to other minarets in al-Andalus and Morocco.[33]: 63 Around the same time, in 756, he also sponsored the construction of a similar (though simpler) minaret for the Qarawiyyin Mosque, while the Umayyad governor of Fes sponsored the construction of a similar minaret for the Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque across the river.[33]: 63–66

Starting in the 11th century, the Berber-led Almoravid and Almohad empires, which were based in Morocco but also controlled al-Andalus, were instrumental in combining the artistic trends of both North Africa and al-Andalus, leading to what eventually became the definitive "Hispano-Moorish" or Andalusi-Maghribi style of the region.[7]: 276–328 The famous Almoravid Minbar in Marrakesh, commissioned from a workshop of craftsmen in Cordoba, is one of the examples illustrating this cross-continental sharing of art and forms.[7][78] These traditions of Moorish art and architecture were continued in Morocco (and the wider Maghreb) well after the end of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula.[3][33][35]

Amazigh (Berber)

The Amazigh peoples (commonly called "Berbers" in English) are a linguistically and ethnically diverse group of peoples who constitute the indigenous (pre-Arab) inhabitants of North Africa. They continue to represent a large part of the population in Morocco.[80] In addition to any local traditions of architecture, Amazigh peoples adapted the forms and ideas of Islamic architecture to their own conditions and in turn contributed to the formation of Western Islamic or "Moorish" art, particularly during their political domination of the region over the centuries of Almoravid, Almohad, and Marinid rule.[7][8][81][82]

Given the intermixing of peoples and settlements in the region over the centuries, it is not always easy to separate Amazigh and non-Amazigh architectural features; however, there are architectural types and features associated with predominantly Amazigh areas of Morocco (particularly the rural Atlas mountains and Saharan regions) which are sufficiently distinctive to constitute their own characteristic styles.[8] Because the relevant structures are made of rammed earth or mud-brick, which requires regular maintenance for preservation, the existing examples can rarely be dated reliably past the 19th or even 20th centuries.[81] Nonetheless, some characteristics of Berber architecture in North Africa – such as the regional forms of mosques – have been established for roughly a millennium.[8]

Structures such as agadirs (fortified granaries) and qsūr or qsars (fortified villages; often spelled ksar in singular and ksour in plural) are prominent traditional features of Amazigh architecture in Morocco.[83] Likewise, the landscapes of the Atlas mountains and oases regions of Morocco are marked by numerous kasbahs – or tighremt in Amazigh languages[84] – which in this case refers to tall, fortified structures acting as forts, warehouses, and/or fortified residences.[81][8] These can in turn be decorated with local geometric motifs carved into the mud-brick exteriors.[81][8]

French

.jpg.webp)

The Treaty of Fes established the French Protectorate in 1912. The French resident general Hubert Lyautey appointed Henri Prost to oversee the urban development of cities under his control.[86][87] One important policy with long-term consequences was the decision to largely forego redevelopment of existing historic cities and to deliberately preserve them as sites of historic heritage, still known today as the "medinas". Instead, the French administration built new modern cities (the Villes Nouvelles) just outside the old cities, where European settlers largely resided with modern Western-style amenities. This was part of a larger "policy of association" adopted by Lyautey which favoured various forms of indirect colonial rule by preserving local institutions and elites, in contrast with other French colonial policies that favoured "assimilation".[85][88] The desire to preserve historic cities was also consistent with one of the trends in European ideas about urban planning at the time which argued for the preservation of historic cities in Europe – ideas which Lyautey himself favored.[87] In April 1914, the colonial government promulgated a dahir for the "arrangement, development, and extension of urban plans, easements, and road tolls".[89][90] This dahir included building standards which directly affected the architecture at that time, as follows:

- Buildings could not be higher than four stories.

- Land use regulation required twenty percent of a planned area to be courtyards or gardens.

- Balconies must not overlook neighboring residences.

- Roofs of all buildings should be flat.

The building regulations maintained the country's pre-existing architectural features and balanced the rapid urbanization. Nonetheless, while this policy preserved historic monuments, it also had other consequences in the long-term by stalling urban development in these heritage areas and causing housing shortages in some areas.[85] It also suppressed local Moroccan architectural innovations, as for example in the medina of Fez where Moroccan residents where required to keep their houses – including any newly built houses – in conformity with what the French administration deemed to be the historic indigenous architecture.[88] Scholar Janet Abu-Lughod has argued that these policies created a kind of urban "apartheid" between the indigenous Moroccan urban areas – which were forced to remain stagnant in terms of urban development – and the new planned cities which were mainly inhabited by Europeans and which expanded to occupy lands outside the city which were formerly used by Moroccans.[91][92][85] This separation was partly softened by wealthy Moroccans who started moving into the Villes Nouvelles during this period.[87]

In some cases French officials removed or remodelled more recent pre-colonial Moroccan structures which had been visibly influenced by European styles in order to erase what they deemed as foreign or non-indigenous interference in Moroccan architecture.[88] In turn, French architects constructed buildings in the new cities that conformed to modern European functions and layouts but whose appearance was heavily blended with local Moroccan decorative motifs, resulting in a Mauresque[11] or Neo-Moorish-style architecture. This was especially evident in some cities like the capital of Rabat, where grand new administrative buildings were designed in this style alongside European-style boulevards.[85] In some cases, the French also inserted Moroccan-looking structures in the fabric of the old cities, such as the Bab Bou Jeloud gate in Fes (completed in 1913[93]) and the nearby Collège Moulay Idriss (opened in 1914).[94][88] The new French-built cities also introduced more modernist styles such as Art Deco. This heritage is especially notable in Casablanca,[95] which became the main port city and the country's largest city during this period.[21]

Constructions methods and materials

Rammed earth (pisé)

One of the most common types of construction in Morocco was rammed earth, an ancient building technique found across the Near East, Africa, and beyond.[96][97][98] It is also known as "pisé" (from French) or "tabia" (from Arabic).[2] The ramparts of Fes, Marrakesh, and Rabat, for example, were made with this process, even though some notable structures (like monumental gates) were also built in stone. It generally made use of local materials and was widely used thanks to its low cost and relative efficiency.[96] This material consisted of mud and soil of varying consistency (everything from smooth clay to rocky soil) usually mixed with other materials such as straw or lime to aid adhesion. The addition of lime also made the walls harder and more resistant overall, although this varied locally as some areas had soil which hardened well on its own while others did not.[2] (For example, the walls of Fes and nearby Meknes contain up to 47% lime versus around 17% in Marrakesh and 12% in Rabat.[99]) The technique is still in use today, though the composition and ratio of these materials has continued to change over time as some materials (like clay) have become relatively more costly than others (like gravel).[2][4]: 80

The walls were built from bottom to top one level at a time. Workers pressed and packed in the materials into sections ranging from 50 and 70 cm in length that were each held together temporarily by wooden boards. Once the material was settled, the wooden restraints could be removed and the process was repeated on top of the previously completed level.[97][99] This process of initial wooden scaffolding often leaves traces in the form of multiple rows of little holes visible across the face of the walls.[4] In many cases walls were covered with a coating of lime, stucco, or other material to give them a smooth surface and to better protect the main structure.[2]

This type of construction required consistent maintenance and upkeep, as the materials are relatively permeable and are more easily eroded by rain over time; in parts of Morocco, (especially near the Sahara) kasbahs and other structures made with a less durable composition (typically lacking lime) can begin to crumble apart in less than a couple of decades after they've been abandoned.[2][100] As such, old structures of this type remain intact only insofar as they are continuously restored; some stretches of wall today appear brand new due to regular maintenance, while others are crumbling.

Brick and stone

In addition to rammed earth, brick and (especially in desert regions) mudbrick were also common types of materials for the construction of houses, civic architecture, and mosques.[3][101][102] Many medieval minarets, for example, are made in brick, in many cases covered with other materials for decoration.[3][101] Stone masonry was also used in many notable monuments, especially in the Almohad period. The monumental Almohad gates of Bab Agnaou, Bab er-Rouah, and the main gate of the Udayas Kasbah (Bab Oudaia) made extensive use of carved stone.[3][29] The major Almohad minarets of the same period demonstrate the relative variability in construction material and methods, depending on the region and the demands of the structure: the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque is built in rubble masonry using sandstone, the Giralda of Seville (in Spain) was made in local brick, the massive but unfinished Hassan Tower in Rabat was made in stone, and the minaret of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh was made with a base of rubble stone and a main shaft of brick.[3]: 209–211

Wood

Wood was also extensively used, but mostly for ceilings and other elements above eye level such as canopies and upper galleries. Many buildings such as mosques and mausoleums have sloped wood-frame or artesonado-like ceilings, known locally as berchla or bershla,[35][103] often visually enhanced by the use of geometric patterns in their arrangement, sculpting, and painted decoration.[3] Many doorways, street fountains, and mosque entrances are also highlighted with sculpted wood canopies which were characteristic of Moroccan and Moorish architecture.[3] Especially from the Marinid period onward, sculpted wood became a major component of architectural decoration.[5][3]

An ornate berchla ceiling in the 16th-century Saadian Tombs

An ornate berchla ceiling in the 16th-century Saadian Tombs.jpg.webp) Wooden canopy over the entrance of the 14th-century Mosque of Abu al-Hasan

Wooden canopy over the entrance of the 14th-century Mosque of Abu al-Hasan

Wood generally came from Moroccan cedar trees,[35][2][28] still highly valued today, which once grew abundantly on mountain slopes across the country but are now partly endangered and limited to forests of the Middle Atlas.[104][105] Other types of wood were still occasionally used, however. The sculpted wood canopy of the Shrob ou Shouf Fountain in Marrakesh was made of palm wood, for example.[29]: 128 The famous Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque, which was fabricated in Cordoba (Spain) before being shipped to Marrakesh, was made primarily of cedar wood but its marquetry decoration was enhanced with more exotic woods of different colors such as jujube and African blackwood.[78]

Other materials for decoration

.jpg.webp)

A very prominent and distinctive element of Moroccan and Moorish architecture is its heavy use of carved stucco for decoration across walls and ceilings.[3][5] Stucco, which is relatively cheap and easily sculpted, was carved and painted with motifs from a large repertoire including floral and vegetal motifs (arabesques), geometric patterns, calligraphic compositions, and muqarnas forms.[5][3] (These were also common features in sculpted wood decoration.)

Tilework, particularly in the form of mosaic tilework called zellij, was a standard decorative element along lower walls and for the paving of floors. It consisted of hand-cut pieces of faience in different colours fitted together to form elaborate geometric motifs, often based on radiating star patterns.[5][3] Zellij made its appearance in the region during the 10th century and became widespread by the 14th century during the Marinid period.[5] It may have been inspired or derived from Byzantine mosaics and then adapted by Muslim craftsmen for faience tiles.[5] The tiles are first fabricated in glazed squares, typically 10 cm per side, then cut by hand into a variety of pre-established shapes (usually memorized by heart) necessary to form the overall pattern.[2] This pre-established repertoire of shapes combined to generate a variety of complex patterns is also known as the hasba method.[106] Although the exact patterns vary from case to case, the underlying principles have been constant for centuries and Moroccan craftsmen are still adept at making them today.[2][106]

Metal, particularly bronze and copper, was also used to decorate or protect certain elements. Notably, the doors of many medieval mosques and madrasas were covered with bronze or copper plating which was carved and chiseled with geometric, arabesque, and calligraphic motifs.[5] The oldest surviving bronze artworks in Moorish-Moroccan art, for example, are the 12th-century bronze fittings found on several doors of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes.[27]

Architectural features

Horseshoe arch

Perhaps the most characteristic arch type of Moroccan and western Islamic architecture generally is the so-called "Moorish" or "horseshoe" arch. This is an arch where the curves of the arch continue downward past the horizontal middle axis of the circle and begin to curve towards each other, rather than just being semi-circular (forming half a circle only).[2]: 15 This arch profile became nearly ubiquitous in the region from the very beginning of the Islamic period.[3]: 45 The origin of this arch appear to date back to the preceding Byzantine period across the Mediterranean, as versions of it appear in Byzantine-era buildings in Cappadocia, Armenia, and Syria. They also appear frequently in Visigothic churches in the Iberian peninsula (5th-7th centuries). Perhaps due to this Visigothic influence, horseshoe arches were particularly predominant afterwards in al-Andalus under the Umayyads of Cordoba, although the Andalusi arch was of slightly different profile than the Visigothic arch.[3]: 163–164 [6] Arches were not only used for supporting the weight of the structure above them. Blind arches and arched niches were also used as decorative elements. The mihrab (niche symbolizing the qibla) of a mosque was almost invariably in the shape of horseshoe arch.[3]: 164 [2] Starting in the Almoravid period, the first pointed or "broken" horseshoe arches began to appear in the region and became more widespread during the Almohad period. This arch is likely of North African origin, since pointed arches were already present in earlier Fatimid architecture further east.[3]: 234

Polylobed arch

Polylobed (or multifoil) arches, have their earliest precedents in Fatimid architecture in Ifriqiya and Egypt and had also appeared in Andalusi architecture such as the Aljaferia palace. In the Almoravid and Almohad periods, this type of arch was further refined for decorative functions while horseshoe arches continued to be standard elsewhere.[3]: 232–234 It appears in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen (in Algeria) and the Mosque of Tinmal.[3]: 232

Polylobed arches at the Almoravid Qubba in Marrakesh

Polylobed arches at the Almoravid Qubba in Marrakesh A polylobed arch in the Mosque of Tinmal

A polylobed arch in the Mosque of Tinmal

"Lambrequin" arch

The so-called "lambrequin" arch,[3][2] with a more intricate profile of lobes and points, was also introduced in the Almoravid period, with an early appearance in the funerary section of the Qarawiyyin Mosque dating from the early 12th century.[3]: 232 It then became common in subsequent Almohad and Marinid architecture (as well as Nasrid architecture in Spain), often to highlight the arches near the mihrab area of a mosque.[3] This type of arch is also sometimes referred to as a "muqarnas arch" due to its similarities with a muqarnas profile and because of its speculated derivation from the use of muqarnas itself.[3]: 232 This type of arch was indeed commonly used with muqarnas sculpting along the intrados (inside surfaces) of the arch.[3][101][2]

Lambrequin arches in the Mosque of Tinmal

Lambrequin arches in the Mosque of Tinmal.jpg.webp) A lambrequin arch with muqarnas in the Madrasa al-Attarine, Fes

A lambrequin arch with muqarnas in the Madrasa al-Attarine, Fes

Floral and vegetal motifs

Arabesques, or floral and vegetal motifs, derive from a long tradition of similar motifs in Syrian, Hellenistic, and Roman architectural ornamentation.[3][2] Early arabesque motifs in Umayyad Cordoba, such as those seen at the Great Mosque or Madinat al-Zahra, continued to make use of acanthus leaves and grapevine motifs from this Hellenistic tradition. Almoravid and Almohad architecture made more use of a general striated leaf motif, often curling and splitting into unequal parts along an axis of symmetry.[3][2] Palmettes and, to a lesser extent, seashell and pine cone images were also featured.[3][2] In the late 16th century, Saadian architecture sometimes made use of a mandorla-type (or almond-shaped) motif which may have been of Ottoman influence.[35]: 128

Arabesque motifs and a palmette image carved into the spandrel of the Marinid gate at Chellah, Rabat

Arabesque motifs and a palmette image carved into the spandrel of the Marinid gate at Chellah, Rabat

Arabesques carved in stucco over an archway in the al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes

Arabesques carved in stucco over an archway in the al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes

"Interlacing" motifs (sebka and darj wa ktaf)

Various types of interlacing lozenge-like motifs are heavily featured on the surface of minarets starting in the Almohad period (12th-13th centuries) and are later found in other decoration such as carved stucco along walls in Marinid (and Nasrid) architecture, eventually becoming a standard feature in the Moroccan ornamental repertoire in combination with arabesques.[2][3] This motif, typically called sebka (meaning "net"),[76]: 80 [107] is believed by some scholars to have originated with the large interlacing arches in the 10th-century extension of the Great Mosque of Cordoba by Caliph al-Hakam II.[3]: 257–258 It was then miniaturized and widened into a repeating net-like pattern that can cover surfaces. This motif, in turn, had many detailed variations. One common version, called darj wa ktaf ("step and shoulder") by Moroccan craftsmen, makes use of alternating straight and curved lines which cross each other on their symmetrical axes, forming a motif that looks roughly like a fleur-de-lys or palmette shape.[3]: 232 [2]: 32 Another version, also commonly found on minarets in alternation with the darj wa ktaf, consists of interlacing multifoil/polylobed arches which form a repeating partial trefoil shape.[2]: 32, 34

.jpg.webp) A sebka or darj wa ktaf motif on one of the facades of the Hassan Tower in Rabat

A sebka or darj wa ktaf motif on one of the facades of the Hassan Tower in Rabat Another variation on the sebka motif, with a trefoil-like shape, on one of the facades of the minaret of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh

Another variation on the sebka motif, with a trefoil-like shape, on one of the facades of the minaret of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh Sebka motif filled with arabesques in the carved stucco decoration of the Ben Youssef Madrasa

Sebka motif filled with arabesques in the carved stucco decoration of the Ben Youssef Madrasa Darj wa ktaf motif on Bab Mansour in Meknes

Darj wa ktaf motif on Bab Mansour in Meknes

Geometric patterns

Geometric patterns, most typically making use of intersecting straight lines which are rotated to form a radiating star-like pattern, were common in Islamic architecture generally and across Moroccan architecture. These are found in carved stucco and wood decoration, and most notably in zellij mosaic tilework. Other polygon motifs are also found, often in combination with arabesques.[3][2]

Twelve-pointed star motifs in zellij tilework at the Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh

Twelve-pointed star motifs in zellij tilework at the Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh.jpg.webp) Geometric patterns in zellij tilework at the Al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes

Geometric patterns in zellij tilework at the Al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes.jpg.webp) Geometric motifs on the bronze plating of the doors of the Al-Attarine Madrasa

Geometric motifs on the bronze plating of the doors of the Al-Attarine Madrasa_(cropped).jpg.webp) Geometric patterns in a wooden ceiling in the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh

Geometric patterns in a wooden ceiling in the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh

Epigraphy and Arabic calligraphy

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Many Islamic monuments feature inscriptions of one kind or another which serve to either decorate or inform, or both. Arabic calligraphy, as in other parts of the Muslim world, was also an art form. Many buildings had foundation inscriptions which record the date of their construction and the patron who sponsored it. Inscriptions could also feature Qur'anic verses, exhortations of God, and other religiously significant passages. Early inscriptions were generally written in the Kufic script, a style where letters were written with straight lines and had fewer flourishes.[3][2]: 38 At a slightly later period, mainly in the 11th century, Kufic letters were enhanced with ornamentation, particularly to fill the empty spaces that were usually present above the letters. This resulted in the addition of floral forms or arabesque backgrounds to calligraphic compositions.[3]: 251 In the 12th century a more "cursive" script began to appear, though it only became commonplace in monuments from the Marinid period (13th-14th century) onward.[3]: 250, 351–352 [2]: 38 Kufic was still employed, especially for more formal or solemn inscriptions such as religious content.[2]: 38 [3]: 250, 351–352 By contrast, Kufic script was also used in a more strictly decorative form, as the starting point for an interlacing motif that was could be woven into a larger arabesque background.[3]: 351–352

Late 12th-century Kufic inscription carved into stone on the Almohad gate of Bab Agnaou in Marrakesh

Late 12th-century Kufic inscription carved into stone on the Almohad gate of Bab Agnaou in Marrakesh.jpg.webp) Kufic script with ornamental flourishes, painted on tile

Kufic script with ornamental flourishes, painted on tile.jpg.webp) Arabic calligraphic inscription carved into stucco in the early 14th-century al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes

Arabic calligraphic inscription carved into stucco in the early 14th-century al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes.jpg.webp) Arabic calligraphic inscription carved into wood in the early 14th-century Sahrij Madrasa in Fes, surrounded by other arabesque decoration

Arabic calligraphic inscription carved into wood in the early 14th-century Sahrij Madrasa in Fes, surrounded by other arabesque decoration

Muqarnas

Muqarnas, sometimes also called "honeycomb" or "stalactite" carvings, consist of a three-dimensional geometric prismatic motif which is among the most characteristic features of Islamic architecture. This technique originated further east in Iran before spreading across the Muslim world.[3]: 237 It was first introduced into Morocco by the Almoravids, who made early use of it in early 12th century in the Qubba Ba'adiyyin in Marrakesh and in the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes.[29][31][3]: 237 While the earliest forms of muqarnas in Islamic architecture were used as squinches or pendentives at the corners of domes,[3]: 237 they were quickly adapted to other architectural uses. In the western Islamic world they were particularly dynamic and were used, among other examples, to enhance entire vaulted ceilings, fill in certain vertical transitions between different architectural elements, and even to highlight the presence of windows on otherwise flat surfaces.[3][5][2]

Muqarnas vault above the entrance of the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh

Muqarnas vault above the entrance of the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh Muqarnas above a window in the Bou Inania Madrasa of Meknes

Muqarnas above a window in the Bou Inania Madrasa of Meknes Small muqarnas cupola inside the mihrab of the Mosque of Tinmal

Small muqarnas cupola inside the mihrab of the Mosque of Tinmal.jpg.webp) Detail of muqarnas decoration in the Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh

Detail of muqarnas decoration in the Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh Muqarnas carved in wood in the Dar al-Makhzen of Tangier

Muqarnas carved in wood in the Dar al-Makhzen of Tangier

Decoration in vernacular Amazigh architecture

The vernacular architecture of predominantly Amazigh (Berber) regions in Morocco, such as the Atlas Mountains and southern oases, is notable for the presence of geometric motifs (called lasserift in Amazigh) used to decorate the exterior of rural kasbahs and other prominent homes.[108] These motifs are emblematic of Amazigh architecture and are found in vernacular Amazigh architecture in other parts of North Africa.[108][8] This use of geometric motifs in North African Amazigh architecture is believed to have ancient origins: Henri Terrasse believed they had existed since before the first millennium BC due to their widespread precedents in Asia and elsewhere,[109] while historian Gabriel Camps dates its origins to the presence of Carthaginian culture in the first millennium BC.[108] Nonetheless, the art of these decorations have evolved and changed over time.[84]: 39

The motifs typically consist of a combination of circles, rosettes, hexagons, lozenges, chevrons, chequer-boards, and crosses.[8][108] These structures were built of rammed earth and mudbrick, and so the motifs were traditionally created by building the walls with recesses along their surface or by laying some bricks further back to form recesses.[84]: 34 Starting in the early 20th century, however, these motifs began to grow more complex and articulated, in part due to the growing links between the oases regions and the urban culture of major cities like Marrakesh. Patterns made of broader elements formed by recessed bricks and alcoves were replaced with narrower, finer motifs made of lines that were carved directly into the wall surfaces.[84]: 36–39 Salima Naji, a Moroccan architect and author on Berber architecture, notes that these more linear decorations, although more complex, lack the balance and rigorous composition of older motifs.[84]: 38

_06.jpg.webp) Niche and linear decoration at Kasbah Taourirt in Ouarzazate

Niche and linear decoration at Kasbah Taourirt in Ouarzazate A tighremt in Ait Benhaddou with decoration

A tighremt in Ait Benhaddou with decoration.jpg.webp) Detail of decoration on a house in Ait Benhaddou

Detail of decoration on a house in Ait Benhaddou Horseshoe arches in the windows of the Kasbah Amridil

Horseshoe arches in the windows of the Kasbah Amridil

Some local mansions, such as the Telouet Kasbah and the Taourirt Kasbah used by the Glaoui clan, also hosted decoration and craftsmanship more typical of the imperial cities of Morocco and of the broader Islamic architectural styles prevalent there,[110][111] or in some cases mixed those traditions with local decorative traditions.[84] Horseshoe arches, widely used in architectural traditions throughout the region, were also widely used in local Amazigh architecture. As the arches served no structural purposes in rammed-earth architecture, their function was mainly decorative, used for doorways, windows, and blind arches or niches.[8][108]

In addition to the exterior wall motifs, doors and ceilings could were also decorated in larger residences. Two main types of ceilings are attested: wood ceilings and reed ceilings.[84]: 62 The first type typically consists of wooden panels, whose surfaces were painted with local geometric motifs, Islamic geometric motifs familiar in the major cities, and epigraphic inscriptions. Reed ceilings, which were constructed with wattles of reed stems, could be arranged to form basic two or three-dimensional patterns and then enhanced with red and black paint.[84]: 62–69

Traditional doors, made of wood, were carved and painted with a variety of geometric motifs which were probably influenced by urban Islamic motifs but interpreted by local craftsmen, often with less precision.[84]: 44–51 Doors could also be painted or carved with talismanic seals, resembling medallion or amulet-like compositions containing written words and other symbols such as the seal of Solomon, mihrab-like motifs, and representations of the khamsa.[84]: 53–59 Salima Naji notes that some of these decorations were intended to have magical properties, but that in some cases the art forms have likely persisted without the magical connotations.[84]: 57

Types of structures

The following is a summary of the different major types and functions of buildings and architectural complexes found in historic Moroccan architecture.

Mosques

_(2).jpg.webp)

Mosques are the main place of worship in Islam. Muslims are called to prayer five times a day and participate in prayers together as a community, facing towards the qibla (direction of prayer). Every neighbourhood normally had one or many mosques in order to accommodate the spiritual needs of its residents. Historically, there was a distinction between regular mosques and "Friday mosques" or "grand mosques", which were larger and had a more important status by virtue of being the venue where the khutba (sermon) was delivered on Fridays.[26] Friday noon prayers were considered more important and were accompanied by preaching, and also had political and social importance as occasions where news and royal decrees were announced, as well as when the current ruler's name was mentioned. In the early Islamic era of Morocco, there was typically only one Friday mosque per city, but over time Friday mosques multiplied until it was common practice to have one in every neighbourhood or district of the city.[112][101] Mosques could also frequently be accompanied by other facilities which served the community.[101][32]

Mosque architecture in Morocco was heavily influenced from the beginning by major well-known mosques in Tunisia and al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal), two countries from which many Arab and Muslim immigrants to Morocco originated.[21] The Great Mosque of Kairouan and the Great Mosque of Cordoba, in particular, were models of mosque architecture.[3][7] Accordingly, most mosques in Morocco have roughly rectangular floor plans and follow the hypostyle format: they consist of a large prayer hall upheld and divided by rows of horseshoe arches running either parallel or perpendicular to the qibla wall (the wall towards which prayers faced). The qibla (direction of prayer) was always symbolized by a decorative niche or alcove in the qibla wall, known as a mihrab.[2] Next to the mihrab there was usually a symbolic pulpit known as a minbar. The mosque also normally included, close to entrance, a sahn (courtyard) which often had fountains or water basins to assist with ablutions. In early periods this courtyard was relatively minor in proportion to the rest of the mosque, but in later periods it became a progressively larger until it was equal in size to the prayer hall and sometimes larger.[35][101]

Lastly, mosque buildings were distinguished by their minarets: towers from which the muezzin issues the call to prayer to the surrounding city. (This was historically done by the muezzin climbing to the top and projecting his voice over the rooftops, but nowadays the call is issued over modern megaphones installed on the tower.) Moroccan minarets traditionally have a square shaft and are arranged in two tiers: the main shaft, which makes up most of its height, and a much smaller secondary tower above this which is in turn topped by a finial of copper or brass spheres.[3][101] Some Moroccan minarets have octagonal shafts, though this is more characteristic of the northern parts of the country.[5] Inside the main shaft a staircase, and in other cases a ramp, ascends to the top of the minaret.[3][101]

Medieval Moroccan mosques also frequently followed the "T-type" model established in the Almohad period. In this model the aisle or "nave" between the arches running towards the mihrab (and perpendicular to the qibla wall) was wider than the others, as was also the aisle directly in front of and along the qibla wall (running parallel to the qibla wall); thus forming a "T"-shaped space in the floor plan of the mosque which was often accentuated by greater decoration (e.g. more elaborate arch shapes around it or decorative cupola ceilings at each end of the "T").[101][35][32]

The whole structure of a mosque was also orientated or aligned with the direction of prayer (qibla), such that mosques were sometimes orientated in a different direction from the rest of the buildings or streets around it.[113] This geographic alignment, however, varied greatly from period to period. Nowadays it is standard practice across the Muslim world that the direction of prayer is the direction of the shortest distance between oneself and the Kaaba in Mecca. In Morocco, this corresponds to a generally eastern orientation (varying slightly depending on your exact position).[114] However, in early Islamic periods there were other interpretations of what the qibla should be. In the western Islamic world (the Maghreb and al-Andalus), in particular, early mosques often had a southern orientation, as can be seen in major early mosques like the Great Mosque of Cordoba and the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes. This was based on a reported hadith of the Prophet Muhammad which stated that "what is between the east and west is a qibla", as well as on a popular view that mosques should not be aligned towards the Kaaba but rather that they should follow the cardinal orientation of the Kaaba itself (which is a rectangular structure with its own geometric axes), which is in turn aligned according to certain astronomical references (e.g. its minor axis is aligned with the sunrise of the summer solstice).[115][114][113]

Synagogues

Although much reduced today, the Jewish community of Morocco has a long history, resulting in the presence of many synagogues across the country (some of which are defunct and some of which are still functioning). Synagogues had a very different layout from mosques but often shared similar decorative trends as the rest of Moroccan architecture, such as colourful tilework and carved stucco,[93][116] though later synagogues were built in other styles too. Notable examples of synagogues in Morocco include the Ibn Danan Synagogue in Fes, the Slat al-Azama Synagogue in Marrakesh, or the Beth-El Synagogue in Casablanca, though numerous other examples exist.[117][118]

Madrasas

The madrasa was an institution which originated in northeastern Iran by the early 11th century and was progressively adopted further west.[3][2] These establishments provided higher education and served to train Islamic scholars, particularly in Islamic law and jurisprudence (fiqh). The madrasa in the Sunni world was generally antithetical to more "heterodox" religious doctrines, including the doctrine espoused by the Almohad dynasty. As such, it only came to flourish in Morocco in the late 13th century, under the Marinid dynasty which succeeded the Almohads.[3] To the Marinids, madrasas also played a part in bolstering the political legitimacy of their dynasty. They used this patronage to encourage the loyalty of the country's influential but independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam.[3][28] Finally, madrasas also played an important role in training the scholars and elites who operated the state bureaucracy.[28]

Madrasas also played a supporting role to major learning institutions like the Qarawiyyin Mosque; in part because, unlike the mosque, they provided accommodations for students who came from outside the city.[2]: 137 [4]: 110 Many of these students were poor, seeking sufficient education to gain a higher position in their home towns, and the madrasas provided them with basic necessities such as lodging and bread.[26]: 463 However, the madrasas were also teaching institutions in their own right and offered their own courses, with some Islamic scholars making their reputation by teaching at certain madrasas.[4]: 141

Madrasas were generally centered around a main courtyard with a central fountain, off which other rooms could be accessed. Student living quarters were typically distributed on an upper floor around the courtyard. Many madrasas also included a prayer hall with a mihrab, though only the Bou Inania Madrasa of Fes officially functioned as a full mosque and featured its own minaret. In the Marinid era, madrasas also evolved to be lavishly decorated.[34][3]

Mausoleums and zawiyas

Most Muslim graves are traditionally simple and unadorned, but in North Africa the graves of important figures were often covered in a domed structure (or a cupola of often pyramidal shape) called a qubba (also spelled koubba). This was especially characteristic for the tombs of "saints" such as walis and marabouts: individuals who came to be venerated for their strong piety, reputed miracles, or other mystical attributes. Many of these existed within the wider category of Islamic mysticism known as Sufism.

Some of these tombs became the focus of entire religious complexes built around them, known as a zawiya (also spelled zaouia; Arabic: زاوية).[32][3][119] They typically included a mosque, school, and other charitable facilities.[3] Such religious establishments were major centers of Moroccan Sufism and grew in power and influence over the centuries, often associated with specific Sufi Brotherhoods or schools of thought.[32][113] The Saadian dynasty, for example, began as a military force associated with the zawiya and followers of Muhammad al-Jazuli, a major 15th-century Sufi scholar.[32][35] The Alaouites after them also sponsored many zawiyas across the country.[5][32] Some of the most important examples of zawiyas in Morocco include the Zawiya of Moulay Idris I near Meknes, the Zawiya of his son Moulay Idris II in Fes, and the tombs of the Seven Saints in Marrakesh.[32][5]

Funduqs

).jpg.webp)

A funduq (also spelled foundouk or fondouk; Arabic: فندق) was a caravanserai or commercial building which served as both an inn for merchants and a warehouse for their goods and merchandise.[3][2][113] In Morocco some funduqs also housed the workshops of local artisans.[26] As a result of this function, they also became centers for other commercial activities such as auctions and markets.[26] They typically consisted of a large central courtyard surrounded by a gallery, around which storage rooms and sleeping quarters were arranged, frequently over multiple floors. Some were relatively simple and plain, while others, like the Funduq al-Najjarin (or Fondouk Nejjarine) in Fes, were quite richly decorated.[5]

Hammams

Hammams (Arabic: حمّام) are public bathhouses which were ubiquitous in Muslim cities. Many historic hammams have been preserved in cities like Marrakesh[120] and especially Fes, partly thanks to their continued use by locals up to the present day.[62][61] Among the better-known examples of preserved historic hammams in Morocco is the 14th-century Saffarin Hammam in Fes, which has recently undergone restoration and rehabilitation.[62][121][122][61]

Essentially derived from the Roman bathhouse model, hammams normally consisted of four main chambers: a changing room, from which one then moved on to a cold room, a warm room, and a hot room.[3]: 215–216, 315–316 [62] Heat and steam were generated by a hypocaust system which heated the floors. The furnace re-used natural organic materials (such as wood shavings, olive pits, or other organic waste byproducts) by burning them for fuel.[123] The smoke generated by this furnace helped with heating the floors while excess smoke was evacuated through chimneys. Of the different rooms, only the changing room was heavily decorated with zellij, stucco, or carved wood.[3]: 316 The cold, warm, and hot rooms were usually vaulted or domed chambers without windows, designed to keep steam from escaping, but partially lit thanks to small holes in the ceiling which could be covered by ceramic or coloured glass.[3]: 316

Public fountains

As in many Muslim cities, water was provided freely to the public through a number of street fountains, similar to sebils in the former Ottoman Empire. Some fountains were decorated with a canopy of sculpted wood or zellij tilework.[3]: 410–413 Fountains were often attached to the outside of mosques, funduqs, and aristocratic mansions.[26][35] According to Leo Africanus, a traveler and chronicler in the 16th century, there were some 600 fountains in Fes alone.[26]: 236 Well-known examples in Morocco include the Nejjarine Fountain in Fes, the Shrob ou Shouf Fountain in Marrakesh, and the Mouassine Fountain attached to the mosque of the same name.[5][35]

Water supply infrastructure

Moroccan cities and towns were supplied with water through a number of different mechanisms. As elsewhere, most settlements were built near existing water sources such as rivers and oases. However, further engineering was necessary in order to supplement natural sources and in order to distribute the water across the city directly.

In Fes, for example, this was accomplished via a complex network of canals and channels which captured the waters of the Oued Fes (Fes River) and distributed them across the entire city. These water channels (most of them now hidden under buildings) supplied houses, gardens, fountains, and mosques, powered norias (waterwheels), and sustained certain industries such as the tanneries (e.g. the famous Chouara Tannery).[124][102][26] Waterwheels were also used to lift water from these canals and into aqueducts to bring them even further, such as the enormous noria, with a diameter of 26 meters, built by the Marinids to supply their Royal Gardens to the north of Fes el-Jdid.[125]

Marrakesh, located in a more arid environment, was supplied in large part by a system of khettaras, an ingenious and complex system by which an underground channel was dug beneath the slopes in the surrounding countryside until it reached the level of the phreatic zone.[113] This artificial channel was gently sloped to allow water to drain through it, but was sloped less steeply than the natural terrain so that it eventually emerged at the surface. In this way, the khettaras drew water from underground aquifers located on higher ground and brought them to the surface with the use of gravity alone. Once at the surface, the waters ran along canals and were stored in a cistern or water basin, from which they could then be redistributed across the city.[113] This system was created under the Almoravids (who founded the city) and further developed and maintained by their successors.[113]

Oases regions in the desertic areas of Morocco also needed to make extensive use of irrigation and artificial water canals to make agriculture possible. Khettara systems were also used to supplement these water sources, especially as surface waters frequently dried up during the summer months. The Tafilalt oasis region, located along the Ziz River valley, is a notable example of this system.[126][127]

Riads

A riad (sometimes spelled riyad; Arabic: رياض) is an interior garden found in many Moroccan mansions and palaces. It is normally rectangular and divided into four parts along its central axes, with a fountain at its middle.[113] Riad gardens probably originated in Persian architecture (where it is also known as chahar bagh) and became a prominent feature in Moorish palaces in Spain (such Madinat al-Zahra, the Aljaferia and the Alhambra).[113] In Morocco, they became especially widespread in the palaces and mansions of Marrakesh, where the combination of available space and warm climate made them particularly appealing.[113] The term is nowadays applied in a broader way to traditional Moroccan houses that have been converted into hotels and tourist guesthouses.[128][129]

Houses

Traditional Moroccan houses were typically centered around a courtyard or patio, often surrounded by a gallery, from which other rooms and sections branched off.[130][113] Courtyard houses have historical antecedents in the houses and villas of the Greco-Roman Mediterranean world and even earlier in the ancient Middle East.[113] These houses were inward focused: even rich mansions are usually completely unadorned on the outside, with all decoration concentrated on the inside. There were few, if any, large windows on the outside. The entrance, which led to the courtyard, was typically a bent entrance that prevented outsiders in the street from seeing directly inside the house. As with other traditional Moroccan structures, decoration included carved stucco, sculpted and painted wood, and zellij tilework.[130][113]

The central patio/courtyard, known as the wast ad-dar ("middle of the house") was thus the centerpiece of the house. The size and craftsmanship of this interior space was an indication of the status and wealth of its owners, rather than the house's external appearance.[113]: 54 This inward focus of Moroccan house architecture may have been partly supported by the values of Islamic society, which placed emphasis on privacy and encouraged a separation between private family spaces – where women generally lived and worked – and semi-public spaces where outside guests were received. Nonetheless, pre-Islamic traditions of domestic architecture in the Mediterranean and Africa were also at the origin of this model. These two factures likely contributed together to making the courtyard house the near-universal model of traditional Moroccan houses.[113]: 67–68 It is unclear to what extent Moroccan riads and houses were inspired by models imported by immigrants from al-Andalus, where many early examples have also survived, or to what extent they developed locally in parallel with Andalusi versions.[113]: 66–67 [130]: 77–89 What is certain, however, is that there was historically a close cultural and geopolitical relationship between the two lands on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar, and that the palaces of Granada, for example, were thus similar to those of Fes in the same period.[33]: 13 [130]: 77–89

Moroccan house architecture up to 16th century

_from_Golvin_et_al_-_facade_drawing_only.jpg.webp)

A number of historic bourgeois mansions have survived across the country, mostly from the Alaouite era but some dating as far back as the Marinid or Saadian periods in Fes and Marrakesh.[130][113] In Fes, in the early 20th century, one richly decorated house from the beginning of the 14th century (the early Marinid period) was studied and documented by Alfred Bel before it was demolished by its owners.[131] Built in brick, its decoration and form bore very strong similarities with the Marinid madrasas built in Fes in the same period, revealing a shared ornamental repertoire and craftsmanship between madrasas and private houses of rich families. Beyond this, the overall layout was also comparable to the Muslim houses of Granada and demonstrated many classic features of medieval Moroccan houses that are often repeated in later houses. It had a central square courtyard or patio (called the wust ad-dar) surrounded by a two-story gallery, from which rooms opened on every side on both stories. The rooms were wide but relatively shallow in order to keep a generally square floor plan with the courtyard at its center, and the main rooms opened through very tall arched doorways with wooden double doors. Above these doorways on the ground floor were windows that allowed light from the courtyard to enter the rooms behind. While not completely symmetrical, each façade of the courtyard gallery consisted of a tall, wide central arch and two narrow side arches. This arrangement resulted in a cluster of three pillars at the corners of the gallery. The top of the central arch in the lower-floor gallery consisted of a two-tiered or corbelled wooden lintel instead of a round arch, while the two smaller arches to the side were round and much lower. The vertical space above the side arches was filled with ornate stucco decoration based on a sebka motif, similar to some of the decorated surfaces in the Marinid madrasas of the city. The central arch of the second-floor gallery was a round arch whose spandrels were filled with the same kind of stucco decoration, with the two smaller arches to either side having a similar form. The wooden lintels were carved with vegetal motifs as well as with floriated Kufic letters. The lower parts of the brick pillars were covered in zellij tiles. Although the house is gone, pieces of the house's stucco decoration have been preserved in the Dar Batha museum in Fes.[3]: 313–314 [130]

Since the demolition of this early documented medieval house, another Marinid-era house (probably 14th century), known as Dar Sfairia or Dar al-Fasiyin, was studied by Henri Terrasse and Boris Maslow, of similar form but more modest.[132][3]: 313–314 It too was demolished in the late 20th century, however several other houses possibly dating to the Marinid era or to the Saadian era have been studied by Jacques Revault, Lucien Golvin and Ali Amahan in their study of the houses of Fes,[130] all featuring variations on the same overall form as the house studied by Alfred Bel: a central square courtyard surrounded by rooms which opened through tall archway doors, sometimes with windows above the ground floor doorways, and often behind a two story gallery. While most houses have a simpler arrangement of one pillar at every corner of the gallery, larger mansions such as Dar Lazreq (owned by the Lazreq family since the 19th century) and Dar Demana (built by the Ouazzani family) have clusters of three pillars at every corner (for twelve pillars in total), repeating the motif of a large central opening flanked by smaller arches on every side of the gallery.[130] Wooden lintels forming corbelled arches in the galleries is a common feature throughout, sometimes carved with vegetal or epigraphic decoration and sometimes supported by ornate stucco corbels. Dar Lazreq, which likely dates to the 15th or 16th century, features the same kind of sebka-based stucco decoration in the spaces above the small side arches of its courtyard gallery.[130] Dar Demana, which dates in style to the Marinid period but may have been founded earlier, is distinguished further by a short lookout tower (a menzeh) on its roof terrace, allowing its owners to enjoy a better view of the city[130] – a feature present in many mansions in both Fes and Marrakesh.[113]: 269 It is also adjoined by a separate riad garden, a feature which was not previously common in the architecture of Fes.[130] Both Dar Demana and Dar Lazreq were recently restored in the 2010s.[133]