Neferefre

Neferefre Isi (fl. 25th century BC; also known as Raneferef, Ranefer and in Greek as Χέρης, Cherês) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty during the Old Kingdom period. He was most likely the eldest son of pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai and queen Khentkaus II. He was known as prince Ranefer before he ascended to the throne.

| Neferefre | |

|---|---|

| Raneferef, Neferefra, Noufirre, Noufirefre, Cherês | |

Statuette of Neferefre, painted limestone[1] | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | Probably two years or less[2] in the early to mid 25th century BC [note 1] (Fifth Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Neferirkare Kakai (most likely) or Shepseskare |

| Successor | Shepseskare (most likely) or Nyuserre Ini |

| Consort | likely Khentkaus III |

| Children | uncertain, either Menkauhor Kaiu ♂ or Shepseskare ♂ Nakhtsare ♂ Conjectural: Kakaibaef ♂ |

| Father | Neferirkare Kakai |

| Mother | Khentkaus II |

| Died | aged 20–23[21] |

| Burial | Pyramid of Neferefre |

| Monuments | Pyramid Netjeribau Raneferef Sun temple Hotep-Re |

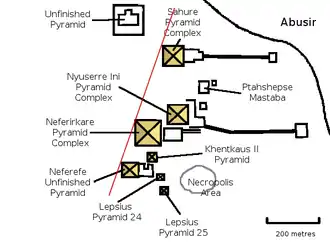

Neferefre started a pyramid for himself in the royal necropolis of Abusir called Netjeribau Raneferef, which means "The bas of Neferefre are divine". The pyramid was never finished, with a mason's inscription showing that works on the stone structure were abandoned during or shortly after the king's second year of reign. Together with the sparsity of attestations contemporaneous with his reign, this is taken by Egyptologists as evidence that Neferefre died unexpectedly after two to three years on the throne. Neferefre was nonetheless buried in his pyramid, hastily completed in the form of a mastaba by his second successor and presumably younger brother, pharaoh Nyuserre Ini. Fragments of his mummy were uncovered there, showing that he died in his early twenties.

Little is known of Neferefre's activities beyond laying the foundations of his pyramid and attempting to finish that of his father. A single text shows that Neferefre had planned or just started to build a sun temple called Hotep-Re, meaning "Ra is content" or "Ra's offering table", which possibly never functioned as such given the brevity of the king's reign. After his death, Neferefre might have been succeeded by an ephemeral and little-known pharaoh, Shepseskare, whose relation with Neferefre remains highly uncertain and debated.

Sources

Contemporaneous

There are very few archaeological sources contemporaneous with Neferefre, a fact which is now seen by Egyptologists, including Miroslav Verner, to imply a very short reign.[22] Verner knew of only one inscription dated to his rule. It was left by the builders of his pyramid on a corner block at the end of the corridor leading to the pyramid substructures.[23] The inscription was written on the fourth day of the Akhet season in the year of first occurrence of the cattle count, an event consisting of counting the livestock throughout the country to evaluate the amount of taxes to be levied. It is traditionally believed that such counts occurred every two years during the Old Kingdom[24] although recent reappraisals have led Egyptologists to posit a less regular and somewhat more frequent count.[25] Therefore, the inscription must refer to Neferefre's first or second year on the throne, and his third year at the very latest.[note 3][26] Finally, a few artefacts dated to Neferefre's rule or shortly after have been uncovered in his mortuary complex and elsewhere in Abusir,[note 4] such as clay seals bearing his Horus name.[28]

Some of the Abusir Papyri discovered in Khentkhaus II's temple and dating to the mid- to late Fifth Dynasty mention the mortuary temple and funerary cult of Neferefre. They constitute a written source near-contemporaneous with his reign, which not only confirmed the existence of Neferefre's pyramid complex at a time when it had not yet been identified,[29] but also gives details regarding the administrative organisation and importance of the funerary cult of the king in Ancient Egyptian society.[30]

Historical

Neferefre is present on several Ancient Egyptian king lists, all dating to the New Kingdom period. The earliest such list mentioning Neferefre is the Abydos King List, written during the reign of Seti I (fl. 1290–1279 BC), and where his prenomen occupies the 29th entry, between those of Neferirkare Kakai and Nyuserre Ini.[31] During the subsequent reign of Ramses II (fl. 1279–1213 BC), Neferefre appears on the Saqqara Tablet,[32] this time after Shepseskare, that is as a second successor to Neferirkare Kakai. Owing to a scribal error, Neferefre's name on this list is given as "Khanefere" or "Neferkhare".[33] Neferefre's prenomen was in all probability also given on the Turin canon (third column, 21st row), which dates to the same period as the Saqqara tablet, but it has since been lost in a large lacuna affecting the document. Nonetheless, the part of the reign length attributed to Neferefre by the canon is still legible, with a single stroke sign indicating one year of reign to which a decade could in principle be added, as the corresponding sign would be effectively lost in the lacuna of the document.[23]

Neferefre was also likely mentioned in the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BC) by the Egyptian priest Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived to this day and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. Africanus relates that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Nefercherês → Sisirês → Cherês" for the mid-Fifth Dynasty. Nefercherês, Sisirês and Cherês are believed to be the hellenized forms for Neferirkare, Shepseskare and Neferkhare (that is Neferefre), respectively. Thus, Manetho's reconstruction of the Fifth Dynasty is in good agreement with the Saqqara tablet.[31] In Africanus' epitome of the Aegyptiaca, Cherês is reported to have reigned for 20 years.[34]

Family

Parents and siblings

Neferefre was, in all likelihood, the eldest son of his predecessor pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai with queen Khentkaus II.[3][5][35] This is shown by a relief on a limestone slab discovered in a house in the village near Abusir[36] and depicting Neferirkare and his wife Khentkaus with "the king's eldest son Ranefer",[note 5][37] a name identical with some variants of Neferefre's own.[38] This indicates that Ranefer was Neferefre's name when he was still only a crown prince, that is, before his accession to the throne.[39]

Neferirkare and Khentkaus had at least another son, the future king Nyuserre Ini. In addition, since the relation between Shepseskare and Neferefre remains uncertain, it is possible that the two were brothers too, as suggested by the Egyptologist Silke Roth,[40] although other hypotheses on the matter have been proposed: Verner sees Shepseskare as a son of Sahure and hence Neferefre's uncle, while Jaromír Krejčí believes Shepseskare was Neferefre's son.[41] Finally, yet another brother,[42] possibly younger[43] than both Neferefre and Nyuserre has also been proposed: Iryenre, a prince iry-pat[note 6] whose filiation is suggested by the fact that his funerary cult was associated with that of his mother, both having taken place in the temple of Khentkaus II.[45][46]

Consort and children

Until 2014, no consort of Neferefre was known.[41][47] Late in that year, the mastaba of Khentkaus III was discovered by archaeologists from the Czech Institute of Egyptology working in Abusir, south east of Neferefre's pyramid.[48][49][50] The location and date of the tomb as well as inscriptions found in it strongly suggest that Khentkaus III was Neferefre's queen.[51] Indeed, not only was Khentkaus III presumably buried during the few decades following Neferefre's reign, but her mastaba is also in close proximity to his pyramid,[note 7] and she bore the title of "king's wife", proving that she was a queen.[48]

In addition, Khentkaus III was also called "king's mother" by inscriptions in her tomb, indicating that her son had become pharaoh. Since Neferefre's second successor Nyuserre Ini is known to have been his brother rather than his son, and since Khentkaus III might have been buried during Nyuserre's reign, as indicated by mud seals,[48] this only leaves either Neferefre's ephemeral successor Shepseskare or Nyuserre's successor Menkauhor Kaiu as possibilities.[48] There is an ongoing debate in Egyptology concerning these two alternatives. Verner posits that Shepseskare was an uncle of Neferefre and therefore that Menkauhor Kaiu was Neferefre's son. Meanwhile, Krejčí views the opposite hypothesis, that Shepseskare was Neferefre's son with Khentkaus III, as more probable.[41]

Two further sons of Neferefre and Khentkaus III have been proposed by Verner: the "king's son" Nakhtsare,[54] whose filiation is supported by the general date and location of his tomb,[41] and Kakaibaef, a member of the elite buried in Abusir.[54] Krejčí notes the lack of the titular "king's son" in relation to Kakaibaef, thereby emphasizing the conjectural nature of Verner's assertion.[41]

Reign

Accession to the throne

Two competing hypotheses exist in Egyptology to describe the succession of events running from the death of Neferirkare Kakai, third king of the Fifth Dynasty, to the coronation of Nyuserre Ini, sixth ruler of the dynasty. Relying on historical sources, most notably the Saqqara king list and Manetho's Aegyptiaca, where Neferefre is said to have succeeded Shepseskare,[34] many Egyptologists such as Jürgen von Beckerath and Hartwig Altenmüller have traditionally believed[55] that the following royal succession took place: Neferirkare Kakai → Shepseskare → Neferefre Isi → Nyuserre Ini.[5][56] In this scenario, Neferefre would be the father of Nyuserre, who would have become pharaoh after the former's unexpected death.[5][57]

This view was challenged at the turn of the millennium, most notably by Verner,[58][59][60] who has been responsible for the archaeological excavations of the Fifth Dynasty royal necropolis of Abusir since 1976. Firstly, there is the relief, mentioned earlier, showing that Neferefre was in all likelihood Neferirkare's eldest son.[39][61]

Secondly, excavations of Neferefre's pyramid have yielded his mummy, which showed that he was 18 to 20 years of age at the death of Neferirkare.[62] Consequently, as the previous king's eldest son, in his late teens to early twenties, Neferefre was in optimal position to ascend the throne. Positing that Shepseskare reigned between Neferefre and his father would thus require an explanation as to why and how Shepseskare's claim to the throne could have been stronger than Neferefre's.[63]

Thirdly, archaeological evidences indicate that Shepseskare most likely reigned for only a few weeks to a few months at the most rather than seven years as credited to him in the Aegyptiaca,[13][55] a hypothesis already supported by Nicolas Grimal as early as 1988.[67] Indeed, Shepseskare is the least known Fifth Dynasty king, with only two seals[68][69] and a few seal impressions bearing his name known as of 2017,[70][71][72][73] a paucity of attestations suggesting a very short reign. This is also supported by the state of Shepseskare's unfinished pyramid, which "was interrupted [and] corresponds to the work of several weeks, perhaps no more than one or two months".[74]

Fourthly, archaeological evidence also favors dating Shepseskare's reign to after Neferefre's.[75] Some of the few seal impressions bearing Shepseskare's name have been discovered in the oldest part of Neferefre's mortuary temple,[76] which was not built until Neferefre's death.[77] This seems to indicate that Shepseskare made offerings for the funerary cult of Neferefre, who must therefore have reigned before him.[77][78] Another argument concerns the alignment of pyramids of Sahure, Neferirkare Kakai and Neferefre: they form a line pointing to Heliopolis, just as the three pyramids of Giza do.[note 8][66] In contrast, Shepseskare's unfinished pyramid does not fall on the line to Heliopolis, which strongly suggests that Neferefre's pyramid had already been in place when Shepseskare started to build his.[79] Lastly, while Shepseskare is noted as the immediate predecessor of Neferefre in the Saqqara king list, Verner notes that "this slight discrepancy can be attributed to the [political] disorders of the time and its dynastic disputes."[78] Verner's arguments have convinced a number of Egyptologists, including Darrell Baker, Erik Hornung and Iorwerth Edwards.[13][55][80]

Reign duration

While Neferefre is given a reign of some 20 years in epitomes of Manetho's Aegyptiaca,[34] the current academic view is that this number is an overestimation of his true reign length, which must have been significantly shorter. Before the results of the extensive excavations in Abusir were fully published, Egyptologists following the traditional succession hypothesis credited Neferefre with around a decade of rule, based on the paucity of attestations contemporaneous with his reign. For example, von Beckerath and Winfried Barta gave him 11 and 10 years on the throne, respectively.[82][83] This view now has few supporters.[33]

Indeed, since then, Verner has set forth the hypothesis of a reign of no more than two years.[23] His conclusion is based on archaeological evidence: the unfinished state of his intended pyramid, and the general paucity of documents datable to his rule. Verner writes that:

The shape of the tomb of Neferefra...as well as a number of other archaeological finds clearly indicate that the construction of the king's funerary monument was interrupted, owing to the unexpected early death of the king. The plan of the unfinished building had to be basically changed and a decision was taken to hastily convert the unfinished pyramid, (of which only the incomplete lowest step of the core was built), into a "square-shaped mastaba" or, more precisely, a stylized primeval hill. At the moment of the king's death neither the burial apartment was built, nor was the foundation of the mortuary temple laid.[23]

Furthermore, two historical sources conform with the hypothesis of a short reign: the mason's inscription in Neferefre's pyramid was discovered "at about two thirds of the height of the extant core of the monument"[23] and probably refers to Neferefre's first or second year on the throne; and the Turin canon which credits Neferefre with less than two full years of reign.[23] The combination of archaeological and historical evidence led to the consensus that Neferefre's reign lasted "not longer than about two years".[23]

Building activities

Pyramid complex

Pyramid

Neferefre started the construction of a pyramid for himself in the royal necropolis of Abusir, where his father and grandfather had built their own pyramids. It was known to the Ancient Egyptians as Netjeribau Raneferef meaning "The bas of Neferefre are divine".[note 9][84]

Planned with a square base of 108 m (354 ft), the pyramid of Neferefre was to be larger than those of Userkaf and Sahure, but smaller than that of his father Neferirkare.[85] Upon the unexpected death of Neferefre, only its lower courses had been completed,[9] reaching a height of c. 7 m (23 ft).[86] Subsequently, Nyuserre hastily completed the monument by filling its central part with poor quality limestone, mortar and sand.[87] The external walls of the building were given a smooth and nearly vertical covering of gray limestone at an angle of 78° with the ground so as to give it the form of a mastaba, albeit with a square plan rather than with the usual rectangular shape.[88] Finally, the roof terrace was covered with clay into which local desert gravels were pressed, giving it the appearance of a mound in the surrounding desert,[88] and indeed it was by the name "the Mound"[note 10] that the monument was subsequently called by the Ancient Egyptians.[90] Verner has proposed that the monument was completed this way so as to give it the form of the primeval mound, the mound that arose from the primordial waters Nu in the creation myth of the Heliopolitan form of Ancient Egyptian religion.[89]

The monument was used as a stone quarry from the New Kingdom period onwards,[90] but was later preserved from further damages as its appearance of a rough unfinished and abandoned pyramid did not attract the attention of tomb robbers.[88]

Mortuary temple

Works on the mortuary temple in which the funerary cult of the deceased king was to take place had not even started when Neferefe died. In the short 70-day period allowed between a king's death and his burial,[91] Neferefre's successor—possibly the ephemeral Shepseskare[55]—built a small limestone chapel. It was located on the pyramid base platform, in the 5 m (16 ft) gap left between the masonry and the platform edge, where the pyramid casing would have been put in the original plans.[91] This small chapel was completed during Nyuserre's reign.[92] This pharaoh also built a larger mortuary temple for his brother Neferefre, extending over the whole 65 m (213 ft) length of the pyramid side but built of cheaper mudbrick.[93]

The temple entrance comprised a courtyard adorned with two stone and 24 wooden columns.[92] Behind was the earliest hypostyle hall of Ancient Egypt the remains of which can still be detected, its roof supported by wooden columns in the shape of lotus-clusters resting on limestone bases.[80] This hall was possibly inspired by the royal palaces of the time.[94][95] The structure housed a large wooden statue of the king as well as statues of prisoners of war.[92] Storage rooms for the offerings were located to the north of the hall. In these rooms several statues of Neferefre were discovered, including six heads of the kings,[80] making Neferefre the Fifth Dynasty king with the most surviving statues.[96] East of the main hall was the "Sanctuary of the Knife" which served as a slaughterhouse for the rituals. Two narrow rooms on either sides of the central altar in front of the false door in the main hall may have housed 30 m (98 ft) long[80] solar boats similar to Khufu's.[91]

A significant cache of administrative papyri, comparable in size to the Abusir Papyri found in the temples of Neferirkare and Khentkaus II,[97] was discovered in a storeroom of the mortuary temple of Neferere during a 1982 University of Prague Egyptological Institute excavation.[67] The presence of this cache is due to the peculiar historical circumstances of the mid-Fifth Dynasty.[97] As both Neferirkare and Neferefre died before their pyramid complexes could be finished, Nyuserre altered their planned layout, diverting the causeway leading to Neferirkare's pyramid to his own. This meant that Neferefre's and Neferirkare's mortuary complexes became somewhat isolated on the Abusir plateau. Their priests therefore had to live next to the temple premises in makeshift dwellings,[98] and they stored the administrative records onsite.[97] In contrast, the records of other temples were kept in the pyramid town close to Sahure's or Nyuserre's pyramid, where the current level of ground water means any papyrus has long since disappeared.[99]

Mummy of Neferefre

Fragments of mummy wrappings and cartonnage, as well as scattered pieces of human remains, were discovered on the east side of the burial chamber of the pyramid.[100] The remains amounted to a left hand, a left clavicle still covered with skin, fragments of skin probably from the forehead, upper eyelid and the left foot and a few bones.[101] These remains were in the same archaeological layer as broken pieces from a red granite sarcophagus[100] as well as what remained of the funerary equipment of the king,[note 11] hinting that they could indeed belong to Neferefre.[15] This was further corroborated by subsequent studies of the embalming techniques used on the mummy, found to be compatible with an Old Kingdom date.[15]

The body of the king was probably dried by means of natron and then covered with a thin layer of resin, before being given a white calcareous coating. There is no evidence of brain removal as expected from post-Old Kingdom mummification techniques.[15] A final confirmation of the identity of the mummy is provided by radiocarbon dating, which yielded a 2628–2393 BC interval for the human remains in close correspondence with estimated dates for the Fifth Dynasty.[102] Thus, Neferefre is, with Djedkare Isesi, one of the very few Old Kingdom pharaohs whose mummy has been identified.[62] A bioarchaeological analysis of Neferefre's remains revealed that the king did not partake in strenuous work,[15] died in his early twenties at between 20 and 23 years old and that he may have stood 1.67 m (5.5 ft) to 1.69 m (5.5 ft) in height.[103] The remains of a second individual were discovered in the burial chamber, but those proved to belong to an individual from the Late Middle Ages, who likely lived during the 14th century AD. He had simply been laid on rags and covered with sand for his burial.[15]

Sun temple

Following a tradition established by Userkaf, founder of the Fifth Dynasty, Neferefre planned or built a temple to the sun god Ra. Called Hotep-Re[note 12] by the Ancient Egyptians, meaning "Ra is content"[5] or "Ra's offering table",[104] the temple has not yet been located but is presumably in the vicinity of Neferefre's pyramid in Abusir.[5] It is known solely[105][106] from inscriptions discovered in the mastaba of Ti in North Saqqara,[107][108] where it is mentioned four times.[105] Ti served as an administration official in the pyramid and sun temples of Sahure, Neferirkare and Nyuserre.[108][109]

Given Neferefre's very short reign, the lack of attestations of the Hotep-Re beyond the mastaba of Ti, as well as the lack of priests having served in the temple, Verner proposes that the temple might never have been completed and therefore never functioned as such. Rather it might have been integrated to or its materials reused for the Shesepibre, the sun temple built by Neferefre's probable younger brother, Nyuserre.[110] Incidentally, an earlier discovery by the German archaeological expedition of 1905 under the direction of Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing may vindicate Verner's theory. This expedition uncovered the ruins of large buildings of mudbricks beneath the sun temple of Nyuserre in Abu Gorab.[111] It is possible that these represent the remains of the sun temple of Neferefre, although in the absence of inscriptions confirming this identification, it remains conjectural.[106]

Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai

When he ascended the throne, Neferefre faced the task of completing the pyramid of his father which, with a square base side of 105 m (344 ft) and a height of 72 m (236 ft), is the largest built during the Fifth Dynasty.[112] Although well underway at the death of Neferirkare, the pyramid was lacking its external limestone cladding and the accompanying mortuary temple still had to be built. Neferefre thus started to cover the pyramid surface with limestone and build the foundation of a stone temple on the pyramid's eastern side. His plans were cut short by his death and the duty of finishing the monument fell on Nyuserre's shoulders, who abandoned the task of covering the pyramid face and instead concentrated on building the mortuary temple in bricks and wood.[113]

Funerary cult

Like other pharaohs of the Old Kingdom period, Neferefre benefited from a funerary cult established at his death. Some details of this cult as it occurred during the Fifth Dynasty have survived in the Abusir Papyri. A 10-day yearly festival was held in honor of the deceased ruler during which, on at least one occasion, no less than 130 bulls were sacrificed in the slaughter house of his mortuary temple.[30] The act of mass animal sacrifice testifies to the importance that royal funerary cults had in Ancient Egyptian society, and also shows that vast agricultural resources were devoted to an activity judged unproductive by Verner, something they propose possibly contributed to the decline of the Old Kingdom.[30] The main beneficiaries of these sacrifices were the cult's priests, who consumed the offerings after the required ceremonies.[30]

The funerary cult of Neferefre seems to have ceased at the end of the Old Kingdom or during the First Intermediate Period.[114] Traces of a possible revival of the cult during the later Middle Kingdom are scant and ambiguous. During the Twelfth Dynasty, a certain Khuyankh was buried in the funerary temple of Neferefre. It remains unclear if this was to associate himself closely with the deceased ruler or because other cultic activities in the area constrained the choice of location for Khuyankh's tomb.[115]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Proposed dates for Neferefre's reign: 2475–2474 BC,[3][4][5][6] 2460–2455 BC,[7] 2460–2453 BC,[8] 2448–2445 BC,[9][10] 2456–2445 BC,[11] 2431–2420 BC,[12] 2404 BC,[13] 2399 BC.[14] Finally, the radiocarbon dating of a skin fragment from the mummy of Neferefre has yielded the dates 2628–2393 BC.[15]

- Uncertain translation, might be a diminutive.[16][20]

- The inscription reads rnpt sp tpy, 3bd 4 3ḫt.[23]

- For example, the mastaba of princess Hedjetnebu, a daughter of Djedkare Isesi, yielded clay seals of Neferefre.[27]

- The transliteration of the inscription is [s3-nswt] smsw Rˁ-nfr.[35]

- That is Jrj-pˁt. Often translated as "hereditary prince" or "hereditary noble" and more precisely "concerned with the nobility", this title denotes a highly exalted position.[44]

- Miroslav Bárta, the head of the team of archeologists who made the discovery states that "The unearthed tomb is a part of a small cemetery to the south east of the pyramid complex of King Neferefre which led the team to think that Queen Khentkaus could be the wife of Neferefre hence she was buried close to his funerary complex".[52][53]

- Heliopolis housed the main temple of Ra, which was the most important religious center in the country at the time.[66] The temple was visible from both Abusir and Giza[63] and was probably located where the lines from the Abusir and Giza necropolises intersected.[66]

- Ancient Egyptian transliteration of the name of the pyramid, Nṯr.j-b3w-Rˁ-nfr f.

- The original Ancient Egyptian term iat, used to describe the monument in the Abusir papyri, has also been translated by "hill".[86][89]

- That is fragments from four alabaster canopic jars and pieces from three calcite cases.[100]

- Transcription from the Ancient Egyptian Ḥtp-Rˁ.

References

- Verner 1985b, pp. 272–273, pl. XLV–XLVIII.

- Hornung 2012, p. 484.

- Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- Hawass & Senussi 2008, p. 10.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 599.

- El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, pp. 61–62.

- Schneider 1996, pp. 261–262.

- Clayton 1994, p. 60.

- Málek 2000a, p. 100.

- Rice 1999, p. 141.

- Strudwick 2005, p. xxx.

- von Beckerath 1999, p. 285.

- Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 558.

- Leprohon 2013, p. 39.

- Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- Verner 1985a, p. 284.

- Verner 1985a, pp. 282–283.

- Scheele-Schweitzer 2007, pp. 91–94.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 558 & 560.

- Verner 2001a, p. 401.

- Verner 2001a, p. 400.

- Kanawati 2001, pp. 1–2.

- Verner 2001a, p. 414.

- Verner 1999a, p. 76, fig. 6.

- Verner, Callender & Strouhal 2002, p. 91 & 95.

- Verner, Callender & Strouhal 2002, p. 91.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 135 & 166.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 152.

- Verner 2000, p. 581.

- Mariette 1864, p. 4, pl. 17.

- Baker 2008, p. 251.

- Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- Verner 1985a, p. 282.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 135.

- Posener-Kriéger 1976, vol. II, p. 530.

- Verner 1980, p. 261.

- Verner 1985a, pp. 281–284.

- Roth 2001, p. 106.

- Krejčí, Arias Kytnarová & Odler 2015, p. 40.

- Schmitz 1976, p. 29.

- Verner, Posener-Kriéger & Jánosi 1995, p. 171.

- Strudwick 2005, p. 27.

- Baud 1999b, p. 418, see n. 24.

- Verner, Posener-Kriéger & Jánosi 1995, p. 70.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 64–69.

- Discovery of the tomb of Khentkaus III 2015, Charles University website.

- Krejčí, Arias Kytnarová & Odler 2015, pp. 28–42.

- The Express Tribune 2015.

- Krejčí, Arias Kytnarová & Odler 2015, p. 34.

- Luxor Times 2015.

- Conservation and Archaeology 2016.

- Verner 2014, p. 58.

- Baker 2008, pp. 427–428.

- von Beckerath 1999, pp. 58–59.

- von Beckerath 1999, pp. 56–59.

- Verner 2000.

- Verner 2001a.

- Verner 2001b.

- Baud 1999a, p. 208.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 559.

- Verner 2001a, p. 397.

- Verner 2000, p. 602.

- Lehner 2008, p. 142.

- Verner 2000, p. 586.

- Grimal 1992, p. 77.

- Daressy 1915, p. 94.

- Verner 2000, p. 583.

- Verner 2001a, p. 396.

- Verner 2000, p. 582.

- Verner 2000, pp. 584–585 & fig. 1 p. 599.

- Kaplony 1981, A. Text pp. 289–294 and B. Tafeln, 8lf.

- Verner 2001a, p. 399.

- Verner 2000, p. 585.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 85.

- Verner 2003, p. 58.

- Verner 2002, p. 310.

- Verner 2000, p. 587.

- Edwards 1999, p. 98.

- Verner 1985b, pp. 274–275, pl. XLIX–LI.

- von Beckerath 1997, p. 155.

- Barta 1981, p. 23.

- Grimal 1992, p. 116.

- Grimal 1992, p. 117.

- Lehner 2008, pp. 146–148.

- Lehner 1999, p. 784.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 138.

- Verner 1999b, p. 331.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 139.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 140.

- Lehner 2008, p. 148.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 141.

- Verner 2010, p. 91.

- Verner & Bárta 2006, pp. 146–152.

- Sourouzian 2010, p. 82.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 169.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 79 & 170.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 79 & 169.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 552.

- Baker 2008, p. 250.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, pp. 558–559.

- Strouhal & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 555.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 110.

- Verner 1987, p. 294.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 111.

- Épron et al. 1939–1966, vol. I pl. 37 & 44, vol. II pl. 183.

- Verner 1987, p. 293.

- Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 53.

- Verner 1987, p. 296.

- von Bissing, Borchardt & Kees 1905.

- Grimal 1992, pp. 116–119, Table 3.

- Lehner 2015, p. 293.

- Málek 2000b, p. 245.

- Morales 2006, pp. 328–329.

Sources

- AFP (4 January 2015). "Tomb of previously unknown pharaonic queen found in Egypt". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Barta, Winfried (1981). "Die Chronologie der 1. bis 5. Dynastie nach den Angaben des rekonstruierten Annalensteins". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). De Gruyter. 108 (1): 11–23. doi:10.1524/zaes.1981.108.1.11. S2CID 193019155.

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- "Czech expedition discovers the tomb of an ancient Egyptian unknown queen". Charles University website. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Daressy, Georges Émile Jules (1915). "Cylindre en bronze de l'ancien empire". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte (in French). 15.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1999). "Abusir". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- El-Shahawy, Abeer; Atiya, Farid (2005). The Egyptian Museum in Cairo: a walk through the alleys of ancient Egypt. Cairo: Farid Atiya Press. ISBN 978-9-77-172183-3.

- Épron, Lucienne; Daumas, François; Goyon, Georges; Wild, Henri (1939–1966). Le Tombeau de Ti. Dessins et aquarelles de Lucienne Épron, François Daumas, Georges Goyon, Henri Wild. t. 65 1–3. Le Caire: Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire. OCLC 504839326.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Hawass, Zahi; Senussi, Ashraf (2008). Old Kingdom Pottery from Giza. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-305-986-6.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Kanawati, Naguib (2001). "Nikauisesi, A Reconsideration of the Old Kingdom System of Dating" (PDF). The Rundle Foundation for Egyptian Archaeology, Newsletter. 75.

- Kaplony, Peter (1981). Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reiches. Katalog der Rollsiegel II. Allgemeiner Teil mit Studien zum Köningtum des Alten Reichs II. Katalog der Rollsiegel A. Text B. Tafeln (in German). Bruxelles: Fondation Egyptologique Reine Élisabeth. ISBN 978-0-583-00301-8.

- Krejčí, Jaromír; Arias Kytnarová, Katarína; Odler, Martin (2015). "Archaeological excavation of the mastaba of Queen Khentkaus III (Tomb AC 30)" (PDF). Prague Egyptological Studies. Czech Institute of Archaeology. XV: 28–42.

- Lehner, Mark (1999). "pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Lehner, Mark (2015). "Shareholders: the Menkaure valley temple occupation in context". In Der Manuelian, Peter; Schneider, Thomas (eds.). Towards a new history for the Egyptian Old Kingdom: perspectives on the pyramid age. Harvard Egyptological studies. Vol. 1. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-30189-4.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name: ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Writings from the ancient world, no. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Málek, Jaromir (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c.2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Málek, Jaromir (2000b). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prag: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Mariette, Auguste (1864). "La table de Saqqarah". Revue Archéologique (in French). Paris: Didier. 10: 168–186. OCLC 458108639.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule (1976). Archives du temple funéraire de Néferirkarê-Kakaï (Les papyrus d'Abousir). Bibliothèque d'étude, t. 65/1–2 (in French). Le Caire: Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. OCLC 4515577.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge London & New York. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- Roth, Silke (2001). Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie. Ägypten und Altes Testament (in German). Vol. 46. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04368-7.

- Scheele-Schweitzer, Katrin (2007). "Zu den Königsnamen der 5. und 6. Dynastie". Göttinger Miszellen (in German). Göttingen: Universität der Göttingen, Seminar für Agyptologie und Koptologie. 215: 91–94. ISSN 0344-385X.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-7749-1370-7.

- Schneider, Thomas (1996). Lexikon der Pharaonen (in German). München: Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-42-303365-7.

- Sourouzian, Hourig (2010). "Die Bilderwelt des Alten Reiches". In Brinkmann, Vinzenz (ed.). Sahure. Tod und Leben eines großen Pharao (in German). München: Hirmer. ISBN 978-3-7774-2861-1.

- Strouhal, Eugen; Vyhnánek, Luboš (2000). "The remains of king Neferefra found in his pyramid at Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prag: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 551–560. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- "Tomb of queen Khentakawess III discovered in Egypt". Conservation and Archaeology. 2016.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980). "Die Königsmutter Chentkaus von Abusir und einige Bemerkungen zur Geschichte der 5. Dynastie". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (in German). 8: 243–268. JSTOR 25150079.

- Verner, Miroslav (1985a). "Un roi de la Ve dynastie. Rêneferef ou Rênefer ?". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 85: 281–284.

- Verner, Miroslav (1985b). "Les sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 85: 267–280.

- Verner, Miroslav (1987). "Remarques sur le temple solaire ḤTP-Rˁ et la date du mastaba de Ti". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 87: 293–297.

- Verner, Miroslav; Zemina, Milan (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Praha: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2011.

- Verner, Miroslav; Posener-Kriéger, Paule; Jánosi, Peter (1995). Abusir III : the pyramid complex of Khentkaus. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Praha: Universitas Carolina Pragensis: Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-0535-9.

- Verner, Miroslav (1999a). "Excavations at Abusir Preliminary Report 1997/8". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 126: 70–77. doi:10.1524/zaes.1999.126.1.70. S2CID 192824726.

- Verner, Miroslav (1999b). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0-80-219863-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2000). "Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign?" (PDF). In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 581–602. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2011.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3): 363–418.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav; Callender, Vivienne; Strouhal, Evžen (2002). Abusir VI: Djedkare's family cemetery (PDF). Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University. ISBN 978-80-86277-22-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2013.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3935-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2003). Abusir: The Realm of Osiris. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-723-1.

- Verner, Miroslav; Bárta, Miroslav (2006). Abusir IX: the pyramid complex of Raneferef. The archaeology. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology. ISBN 978-8-02-001357-6.

- Verner, Miroslav (2010). "Several considerations concerning the Old Kingdom royal palace (ˁḥ)" (PDF). Anthropologie, International Journal of Human Diversity and Evolution. XLVIII (2): 91–96.

- Verner, Miroslav (2014). Sons of the Sun. Rise and decline of the Fifth Dynasty. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts. ISBN 978-80-7308-541-4.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Burkard, Günter; Kessler, Dieter (eds.). Die Zeitbestimmung der Ägyptischen Geschichte von der Vorzeit bis 332 v. Chr (in German). Vol. 46. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien. ISBN 978-3805323109.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (in German). Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, Mainz : Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- von Bissing, Friedrich Wilhelm; Borchardt, Ludwig; Kees, Hermann (1905). Das Re-Heiligtum des Königs Ne-Woser-Re (Rathures) (in German). OCLC 152524509.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- "4500 years old tomb of unknown Ancient Egyptian Queen discovered". Luxor Times. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.