Canopic jar

Canopic jars were used by the ancient Egyptians during the mummification process, to store and preserve the viscera of their owner for the afterlife. They were commonly either carved from limestone, or were made of pottery.[1] These jars were used by the ancient Egyptians from the time of the Old Kingdom, until the time of the Late Period or the Ptolemaic Period, by which time the viscera were simply wrapped and placed with the body.[2] The viscera were not kept in a single canopic jar: each jar was reserved for specific organs. The term canopic reflects the mistaken association by early Egyptologists with the Greek legend of Canopus – the boat captain of Menelaus on the voyage to Troy – "who was buried at Canopus in the Delta where he was worshipped in the form of a jar".[3] In alternative versions, the name derives from the location Canopus (now Abukir) in the western Nile Delta near Alexandria, where human-headed jars were worshipped as personifications of the god Osiris.[4]

Canopic jars of the Old Kingdom were rarely inscribed and had a plain lid. In the Middle Kingdom inscriptions became more usual, and the lids were often in the form of human heads. By the Nineteenth Dynasty each of the four lids depicted one of the four sons of Horus, as guardians of the organs.

Use and design

.jpg.webp)

The canopic jars were four in number, each for the safekeeping of particular human organs: the stomach, intestines, lungs, and liver, all of which, it was believed, would be needed in the afterlife. There was no jar for the heart: the Egyptians believed it to be the seat of the soul, and so it was left inside the body.[n 1]

These organs were removed from the body and carefully treated with natron (a natural preservative used by embalmers) and placed in the sacred Canopic Jars.[4]

Many Old Kingdom canopic jars were found empty and damaged, even in undisturbed tombs. Therefore it seems that they were never used as containers. Instead, it seems that they were part of burial rituals and were placed after these rituals, empty.[7]

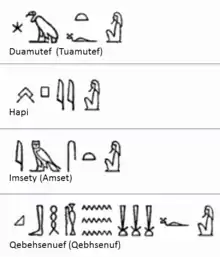

The design of canopic jars changed over time. The oldest date from the Eleventh or the Twelfth Dynasty, and are made of stone or wood.[8] The last jars date from the New Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom the jars had plain lids, though by the First Intermediate Period jars with human heads (assumed to represent the dead) began to appear.[1] Sometimes the covers of the jars were modeled after (or painted to resemble) the head of Anubis, the god of death and embalming. By the late Eighteenth Dynasty canopic jars had come to feature the four sons of Horus.[9] Many sets of jars survive from this period, in alabaster, aragonite, calcareous stone, and blue or green glazed porcelain.[8] The sons of Horus were also the gods of the cardinal compass points.[10] Each god was responsible for protecting a particular organ and was himself protected by a companion goddess. They were:

- Hapi, the baboon-headed god representing the North, whose jar contained the lungs and was protected by the goddess Nephthys. Hapi is often used interchangeably with the Nile god Hapi, though they are actually different gods.

- Duamutef, the jackal-headed god representing the East, whose jar contained the stomach and was protected by the goddess Neith

- Imsety, the human-headed god representing the South, whose jar contained the liver and was protected by the goddess Isis

- Qebehsenuef, the falcon-headed god representing the West, whose jar contained the intestines and was protected by the goddess Serqet.[11]

Early canopic jars were placed inside a canopic chest and buried in tombs together with the sarcophagus of the dead.[8] Later, they were sometimes arranged in rows beneath the bier, or at the four corners of the chamber.[8] After the early periods there were usually inscriptions on the outsides of the jars, sometimes quite long and complex.[12] The scholar Sir Ernest Budge quoted an inscription from the Saïte or Ptolemaic period that begins: "Thy bread is to thee. Thy beer is to thee. Thou livest upon that on which Ra lives." Other inscriptions tell of purification in the afterlife.[13]

In the Third Intermediate Period and later, dummy canopic jars were introduced. Improved embalming techniques allowed the viscera to remain in the body; the traditional jars remained a feature of tombs, but were no longer hollowed out for storage of the organs.[14]

Copious jars were produced, and surviving examples of them can be seen in museums around the world.

In 2020, excavations at Saqqara showed that a woman called Didibastet, whose 2,600-year-old undisturbed tomb was discovered behind a stone wall, was entombed with six canopic jars instead of the traditional four. A CT scan revealed that the jars contain human tissue, suggesting that Didibastet's mummification was possibly the result of a specific request.[15][16]

See also

- Jar burial

- Art of ancient Egypt#Funerary art

- Ushabti

Notes and references

Notes

References

- Shaw and Nicholson, p. 59

- Spencer, p. 115

- David, p. 152

- Strudwick, Helen (2006). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-1-4351-4654-9.

- "British Museum catalogue entry, item number EA9565". British Museum. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- Weighing Of The Heart Scene Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, Swansea University: W1912, accessed 18 November 2011

- Lucie Jirásková: Damage and repairs of the Old Kingdom canopic jars – the case at Abusir. In: Prague Egyptological Studies. 15, 2015, ISSN 1214-3189, pp. 76–85, (online).

- Budge, p. 240

- Shaw and Nicholson, p. 60

- Murray, p. 123

- Gadalla, p. 78

- Budge, p. 242

- Budge, p. 245

- "Canopic Jars", Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London, accessed 18 November 2011

- "Archaeologists Have Uncovered an Ancient Egyptian Funeral Parlor—Revealing That Mummy Embalmers Were Also Savvy Businesspeople". artnet News. 2020-05-06. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- Anonym. "The six organs of the Didibastet mummy, the last mystery of Egypt | tellerreport.com". www.tellerreport.com. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

Sources

- Budge, Sir Edward Wallis (2010) [1925]. The mummy; a handbook of Egyptian funerary archaeology. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01825-8.

- David, A. Rosalie (1999). Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-8160-3312-9.

- Gadalla, Moustafa (2001). Egyptian Divinities – The All who are The One. Greensboro, N.C.: Tehuti Research Foundation. ISBN 1-931446-04-0.

- Murray, Margaret A. (2004) [1963]. The Splendor that was Egypt. Mineola, N.Y: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-43100-0.

- Shaw, Ian; Paul Nicholson (1995). The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9096-2.

- Spencer, A. Jeffrey, ed. (2007). The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1975-5.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan (1994). The Canopic Equipment of the Kings of Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0710304605.