Imhotep

Imhotep (/ɪmˈhoʊtɛp/;[1] Ancient Egyptian: ỉỉ-m-ḥtp "(the one who) comes in peace";[2] fl. late 27th century BCE) was an Egyptian chancellor to the Pharaoh Djoser, possible architect of Djoser's step pyramid, and high priest of the sun god Ra at Heliopolis. Very little is known of Imhotep as a historical figure, but in the 3,000 years following his death, he was gradually glorified and deified.

Imhotep | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Egyptian: Jj m ḥtp | |

| |

| Burial place | Saqqara (probable) |

| Other names | Asclepius (name in Greek) Imouthes (also name in Greek) |

| Occupation | chancellor to the Pharaoh Djoser and High Priest of Ra |

| Years active | c. 27th century BCE |

| Known for | Being the architect of Djoser's step pyramid |

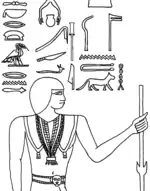

| Imhotep in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Imhotep Jj m ḥtp He who comes in peace | ||||||

Jj m ḥtp | ||||||

Jj m ḥtp | ||||||

| Greek Manetho variants: | Africanus: Imouthes Eusebius: missing Eusebius, AV: missing | |||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Traditions from long after Imhotep's death treated him as a great author of wisdom texts[3] and especially as a physician.[4][5][6][7][8] No text from his lifetime mentions these capacities and no text mentions his name in the first 1,200 years following his death.[9][10] Apart from the three short contemporary inscriptions that establish him as chancellor to the Pharaoh, the first text to reference Imhotep dates to the time of Amenhotep III (c. 1391–1353 BCE). It is addressed to the owner of a tomb, and reads:

The wab-priest may give offerings to your ka. The wab-priests may stretch to you their arms with libations on the soil, as it is done for Imhotep with the remains of the water bowl.

— Wildung (1977)[3]

It appears that this libation to Imhotep was done regularly, as they are attested on papyri associated with statues of Imhotep until the Late Period (c. 664–332 BCE). Wildung (1977)[3] explains the origin of this cult as a slow evolution of intellectuals' memory of Imhotep, from his death onward. Gardiner finds the cult of Imhotep during the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1077 BCE) sufficiently distinct from the usual offerings made to other commoners that the epithet "demigod" is likely justified to describe his veneration.[11]

The first references to the healing abilities of Imhotep occur from the Thirtieth Dynasty (c. 380–343 BCE) onward, some 2,200 years after his death.[10]: 127 [3]: 44

Imhotep is among the few non-royal Egyptians who were deified after their deaths, and until the 21st century, he was one of nearly a dozen non-royals to achieve this status.[12][13] The center of his cult was in Memphis. The location of his tomb remains unknown, despite efforts to find it.[14] The consensus is that it is hidden somewhere at Saqqara.

Historicity

Imhotep's historicity is confirmed by two contemporary inscriptions made during his lifetime on the base or pedestal of one of Djoser's statues (Cairo JE 49889) and also by a graffito on the enclosure wall surrounding Sekhemkhet's unfinished step pyramid.[15][16] The latter inscription suggests that Imhotep outlived Djoser by a few years and went on to serve in the construction of Pharaoh Sekhemkhet's pyramid, which was abandoned due to this ruler's brief reign.[15]

Architecture and engineering

Imhotep was one of the chief officials of the Pharaoh Djoser. Concurring with much later legends, egyptologists credit him with the design and construction of the Pyramid of Djoser, a step pyramid at Saqqara built during the 3rd Dynasty.[17] He may also have been responsible for the first known use of stone columns to support a building.[18] Despite these later attestations, the pharaonic Egyptians themselves never credited Imhotep as the designer of the stepped pyramid, nor with the invention of stone architecture.[19]

Deification

God of medicine

Two thousand years after his death, Imhotep's status had risen to that of a god of medicine and healing. Eventually, Imhotep was equated with Thoth, the god of architecture, mathematics, and medicine, and patron of scribes: Imhotep's cult was merged with that of his own former tutelary god.

He was revered in the region of Thebes as the "brother" of Amenhotep, son of Hapu – another deified architect – in the temples dedicated to Thoth.[20][21]: v3, p104 Because of his association with health, the Greeks equated Imhotep with Asklepios, their own god of health who also was a deified mortal.[22]

According to myth, Imhotep's mother was a mortal named Kheredu-ankh, she too being eventually revered as a demi-goddess as the daughter of Banebdjedet.[23] Alternatively, since Imhotep was known as the "Son of Ptah",[21]: v?, p106 his mother was sometimes claimed to be Sekhmet, the patron of Upper Egypt whose consort was Ptah.

Post-Alexander period

The Upper Egyptian Famine Stela, which dates from the Ptolemaic period (305–30 BCE), bears an inscription containing a legend about a famine lasting seven years during the reign of Djoser. Imhotep is credited with having been instrumental in ending it. One of his priests explained the connection between the god Khnum and the rise of the Nile to the Pharaoh, who then had a dream in which the Nile god spoke to him, promising to end the drought.[24]

A demotic papyrus from the temple of Tebtunis, dating to the 2nd century CE, preserves a long story about Imhotep.[25] The Pharaoh Djoser plays a prominent role in the story, which also mentions Imhotep's family; his father the god Ptah, his mother Khereduankh, and his younger sister Renpetneferet. At one point Djoser desires Renpetneferet, and Imhotep disguises himself and tries to rescue her. The text also refers to the royal tomb of Djoser. Part of the legend includes an anachronistic battle between the Old Kingdom and the Assyrian armies where Imhotep fights an Assyrian sorceress in a duel of magic.[26]

As an instigator of Egyptian culture, Imhotep's idealized image lasted well into the Roman period. In the Ptolemaic period, the Egyptian priest and historian Manetho credited him with inventing the method of a stone-dressed building during Djoser's reign, though he was not the first to actually build with stone. Stone walling, flooring, lintels, and jambs had appeared sporadically during the Archaic Period, though it is true that a building of the size of the step pyramid made entirely out of stone had never before been constructed. Before Djoser, Pharaohs were buried in mastaba tombs.

In popular culture

Imhotep is the antagonistic title character of Universal's 1932 film The Mummy[28] and its 1999 remake, along with a sequel to the remake.[29]

Imhotep was also portrayed in the television show Stargate SG1 as being a false god and an alien known as a Goa’uld.

See also

- Imhotep Museum

- History of ancient Egypt

- Ancient Egyptian architecture

- Ancient Egyptian medicine

References

- "Imhotep". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen [Egyptian Personal Names] (PDF) (in German). Vol. Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen. Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 9. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Wildung, D. (1977). Egyptian Saints: Deification in pharaonic Egypt. New York University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8147-9169-1.

- Osler, William (2004). The Evolution of Modern Medicine. Kessinger Publishing. p. 12.

- Musso, C.G. (2005). Imhotep: The dean among the ancient Egyptian physicians.

- Willerson, J.T.; Teaff, R. (1995). "Egyptian Contributions to Cardiovascular Medicine". Tex Heart I J: 194.

- Highfield, Roger (10 May 2007). "How Imhotep gave us medicine". The Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- Herbowski, L. (2013). "The maze of the cerebrospinal fluid discovery". Anat Res Int. 2013: 5. doi:10.1155/2013/596027. PMC 3874314. PMID 24396600.

- Teeter, E. (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. p. 96.

- Baud, M. (2002). Djéser et la IIIe dynastie [Djoser and the Third Dynasty] (in French). p. 125.

- Hurry, Jamieson B. (2014) [1926]. Imhotep: The Egyptian god of medicine (reprint ed.). Oxford, UK: Traffic Output. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-404-13285-9.

- Troche, Julia (2021). Death, Power and Apotheosis in Ancient Egypt: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- cf. Albrecht, Felix; Feldmeier, Reinhard, eds. (2014). The Divine Father: Religious and philosophical concepts of divine parenthood in antiquity (e-book ed.). Leiden, NL ; Boston, MA: Brill. p. 29. ISBN 978-90-04-26477-9.

- "Lay of the Harper". Reshafim.org.il. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Malek, Jaromir (2002). "The Old Kingdom". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (paperback ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 92–93.

- Kahl, J. (2000). "Old Kingdom: Third Dynasty". In Redford, Donald (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). p. 592. ISBN 0195138228.

- Kemp, B.J. (2005). Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 159.

- Baker, Rosalie; Baker, Charles (2001). Ancient Egyptians: People of the pyramids. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0195122213.

- Romer, John (2013). A History of Ancient Egypt from the First Farmers to the Great Pyramid. Penguin Books. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9780141399713.

- Boylan, Patrick (1922). Thoth or the Hermes of Egypt: A study of some aspects of theological thought in ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–168.

- Lichtheim, M. (1980). Ancient Egyptian Literature. The University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04020-1.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. World Mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio. ISBN 9781576072424. OCLC 52716451.

- Warner, Marina; Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2003). World of Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 296. ISBN 0-292-70204-3.

- "The famine stele on the island of Sehel". Reshafim.org.il. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Ryholt, Kim (2009). Widmer, G.; Devauchelle, D. (eds.). The Life of Imhotep?. IXe Congrès International des Études Démotiques. Bibliothèque d'étude. Vol. 147. Le Caire, Egypt: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. pp. 305–315.

- Ryholt, Kim (2004). "The Assyrian invasion of Egypt in Egyptian literary tradition". Assyria and Beyond. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. p. 501. ISBN 9062583113.

- Allen, James Peter (2005). The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780300107289. Retrieved 17 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- Reid, Danny (24 April 2014). "The Mummy (1932)". Pre-Code.com. Review, with Boris Karloff and David Manners. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Holden, Stephen. "Sarcophagus, be gone: Night of the living undead". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2016 – via NYTimes.com.

Further reading

- Albrecht, Felix; Feldmeier, Reinhard, eds. (6 February 2014). The Divine Father: Religious and philosophical concepts of divine parenthood in antiquity (e-book ed.). Leiden, NL ; Boston, MA: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26477-9. ISSN 1388-3909. Retrieved 30 May 2020 – via Google Books.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2000). The Egyptian Philosophers: Ancient African voices from Imhotep to Akhenaten. Chicago, IL: African American Images. ISBN 978-0-913543-66-5.

- Cormack, Maribelle (1965). Imhotep: Builder in stone. New York, NY: Franklin Watts.

- Dawson, Warren R. (1929). Magician and Leech: A study in the beginnings of medicine with special reference to ancient Egypt. London, UK: Methuen.

- Garry, T. Gerald (1931). Egypt: The home of the occult sciences, with special reference to Imhotep, the mysterious wise man and Egyptian god of medicine. London, UK: John Bale, Sons and Danielsson.

- Hurry, Jamieson B. (1978) [1926]. Imhotep: The Egyptian god of medicine (2nd ed.). New York, NY: AMS Press. ISBN 978-0-404-13285-9.

- Hurry, Jamieson B. (2014) [1926]. Imhotep: The Egyptian god of medicine (reprint ed.). Oxford, UK: Traffic Output. ISBN 978-0-404-13285-9.

- Risse, Guenther B. (1986). "Imhotep and medicine — a re-evaluation". Western Journal of Medicine. 144 (5): 622–624. PMC 1306737. PMID 3521098.

- Wildung, Dietrich (1977). Egyptian Saints: Deification in pharaonic Egypt. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9169-1.

- Wildung, Dietrich (1977). Imhotep und Amenhotep: Gottwerdung im alten Ägypten [Imhotep and Amenhotep: Deification in ancient Egypt] (in German). Deustcher Kunstverlag. ISBN 978-3-422-00829-8.

External links

- "Imhotep (2667–2648 BCE)". BBC History. British Broadcasting Corporation.