Atum

Atum (/ɑ.tum/, Egyptian: jtm(w) or tm(w), reconstructed [jaˈtaːmuw]; Coptic ⲁⲧⲟⲩⲙ Atoum),[3][4] sometimes rendered as Atem or Tem, is an important deity in Egyptian mythology.

| Atum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Atum, finisher of the world | ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | ||||

| Major cult center | Heliopolis | |||

| Personal information | ||||

| Consort | Iusaaset[1] or Nebethetepet[2] | |||

| Children | Shu and Tefnut in some accounts. | |||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Name

Atum's name is thought to be derived from the verb tm which means 'to complete' or 'to finish'. Thus, he has been interpreted as being the "complete one" and also the finisher of the world, which he returns to watery chaos at the end of the creative cycle. As creator, he was seen as the progenitor of the world, the deities and universe having received his vital force or ka.[5]

Origins

Atum is one of the most important and frequently mentioned deities from earliest times, as evidenced by his prominence in the Pyramid Texts, where he is portrayed as both a creator and father to the king.[5] Several writings contradict how Atum was brought into existence. Some state Atum was created by himself by saying his name, while others argue he came out from a blue lotus flower or an egg.[6]

Role

In the Heliopolitan creation myth, Atum was considered to be the first god, having created himself, sitting on a mound (benben) (or identified with the mound itself), from the primordial waters (Nu).[7] Early myths state that Atum created the god Shu and goddess Tefnut by spitting them out of his mouth.[8] One text debates that Atum did not create Shu and Tefnut by spitting them out of his mouth by means of saliva and semen, but rather by Atum's lips.[9] Another writing describes Shu and Tefnut being birthed by Atum's hand. That same writing states that Atum's hand is the title of the god's wife based on her Heliopolitan beginning.[10] Other myths state Atum created by masturbation, with the hand he used in this act representing the female principle inherent within him.[11] Yet other interpretations state that he has made union with his shadow.[12]

In the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians believed that Atum lifted the dead king's soul from his pyramid to the starry heavens.[8] He was also a solar deity, associated with the primary sun god Ra. Atum was linked specifically with the evening sun, while Ra or the closely linked god Khepri were connected with the sun at morning and midday.[13]

In the Book of the Dead, which was still current in the Graeco-Roman period, the sun god Atum is said to have ascended from chaos-waters with the appearance of a snake, the animal renewing itself every morning.[14][15][16]

Atum is the god of pre-existence and post-existence. In the binary solar cycle, the serpentine Atum is contrasted with the scarab-headed god Khepri—the young sun god, whose name is derived from the Egyptian ḫpr "to come into existence". Khepri-Atum encompassed sunrise and sunset, thus reflecting the entire cycle of morning and evening.[17]

Relationship to other gods

Atum was a self-created deity, the first being to emerge from the darkness and endless watery abyss that existed before creation. A product of the energy and matter contained in this chaos, he created his children—the first deities, out of loneliness. He produced from his own sneeze, or in some accounts, semen, Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture. The brother and sister, curious about the primeval waters that surrounded them, went to explore the waters and disappeared into the darkness. Unable to bear his loss, Atum sent a fiery messenger, the Eye of Ra, to find his children. The tears of joy he shed upon their return were the first human beings.[18]

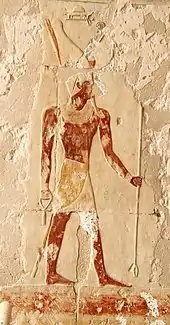

Iconography

Atum is usually depicted as a man wearing either the royal head-cloth or the dual white and red crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, reinforcing his connection with kingship. Sometimes he is also shown as a serpent, the form he returns to at the end of the creative cycle, and also occasionally as a mongoose, lion, bull, lizard, or ape.[5]

Worship

Atum's worship centered on the city of Heliopolis (Egyptian: Annu or Iunu).[5] The only surviving remnant of Heliopolis is the Temple of Re-Atum obelisk located in Al-Masalla of Al-Matariyyah, Cairo. It was erected by Senusret I of the Twelfth Dynasty, and still stands in its original position. The 68 ft (20.73 m) high red granite obelisk weighs 120 tons (240,000 lbs, 108,900 kg, 108.9 tonnes), the weight of about 20 African elephants.

See also

- List of solar deities

- Animal mummy § Miscellaneous animals

- Solar myths

References

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 150

- Richard Wilkinson: The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London, Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7, p.156

- "Coptic Dictionary Online". corpling.uis.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae". Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 99–101

- Dawson, Patricia (2015). Myths of the Ancient Egyptians. Rosen Publishing. p. 31.

- The British Museum. "Picture List" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- "The Egyptian Gods: Atum". Archived from the original on 2002-08-17. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- Lloyd, Aylward M. (2012-11-12). Gods Priests & Men. Routledge. p. 409. doi:10.4324/9780203038277. ISBN 978-1-136-15386-0.

- Lloyd, Aylward M. (2012-11-12). Gods Priests & Men. Routledge. p. 150. doi:10.4324/9780203038277. ISBN 978-1-136-15386-0.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. p. 17-18, 99. ISBN 0500051208.

- "The Egyptian Creation Myth — How the World Was Born". Experience Ancient Egypt. Archived from the original on 2010-01-09.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 205

- Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob; Horst, Pieter Willem van der (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Ellis, Normandi (1995-01-01). Dreams of Isis: A Woman's Spiritual Sojourn. Quest Books. p. 128. ISBN 9780835607124.

- Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena: The linguistic evidence. Rutgers University Press. p. 468. ISBN 9780813536552.

- Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob; Horst, Pieter Willem van der (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2004). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64