Newgrange

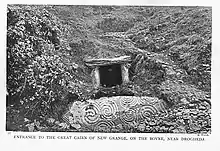

Newgrange (Irish: Sí an Bhrú[1]) is a prehistoric monument in County Meath in Ireland, located on a rise overlooking the River Boyne, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of Drogheda.[2] It is an exceptionally grand passage tomb built during the Neolithic Period, around 3200 BC, making it older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. It is aligned on the winter solstice sunrise. Newgrange is the main monument in the Brú na Bóinne complex, a World Heritage Site that also includes the passage tombs of Knowth and Dowth, as well as other henges, burial mounds and standing stones.[3]

Sí an Bhrú | |

| |

| |

Map of Ireland showing the location of Newgrange | |

| Location | County Meath, Ireland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°41′41″N 6°28′32″W |

| Type | passage grave |

| Width | 76 metres (249 ft) |

| Area | 1.1 acre (0.5 hectare) |

| Height | up to 12 metres (39 ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 3200 BC |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1962–1975 |

| Archaeologists | Michael J. O'Kelly |

| Ownership | Office of Public Works |

| Public access | yes (guided tour only) |

| Official name | Brú na Bóinne |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1993 (17th session) |

| Reference no. | 659 |

| Region | Europe |

Newgrange consists of a large circular mound with an inner stone passageway and cruciform chamber. Burnt and unburnt human bones, and possible grave goods or votive offerings, were found in this chamber. The mound has a retaining wall at the front, made mostly of white quartz cobblestones, and it is ringed by engraved kerbstones. Many of the larger stones of Newgrange are covered in megalithic art. The mound is also ringed by a stone circle. Some of the material that makes up the monument came from as far as the Mournes and Wicklow Mountains. There is no agreement about its purpose, but it is believed it had religious significance. It is aligned so that the rising sun on the winter solstice shines through a 'roofbox' above the entrance and floods the inner chamber. Several other passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with solstices and equinoxes, and Cairn G at Carrowkeel has a similar 'roofbox'.[4][5] Newgrange shares similarities with some other Neolithic monuments in Western Europe; especially Gavrinis in Brittany, which has a similar preserved facing and large carved stones,[6] Maeshowe in Orkney, with its large corbelled chamber,[7] and Bryn Celli Ddu in Wales.

Its initial period of use lasted about 1,000 years. Newgrange then gradually became a ruin, although the area continued to be a site of ritual activity. It featured in Irish mythology and folklore, in which it is said to be a dwelling of the deities, particularly The Dagda and his son Aengus. Antiquarians first began its study in the seventeenth century, and archaeological excavations began in the twentieth century. Archaeologist Michael J. O'Kelly led the most extensive of these from 1962 to 1975 and also reconstructed the front of the monument, a reconstruction that is controversial and disputed.[8] This included an inward-curving dark stone wall to ease visitor access. Newgrange is a popular tourist site and, according to archaeologist Colin Renfrew, is "unhesitatingly regarded by the prehistorian as the great national monument of Ireland" and as one of the most important megalithic structures in Europe.[9]

Description

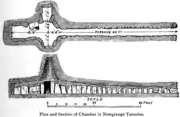

Mound and passage

The Newgrange monument primarily consists of a large mound, built of alternating layers of earth and stones, with grass growing on top and a reconstructed facade of flattish white quartz stones studded at intervals with large rounded cobbles covering part of the circumference. It consists of about 200,000 tonnes of material. The mound is 85 metres (279 ft) wide at its widest point[10] and 12 metres (39 ft) high, and covers 4,500 square metres (1.1 acres) of ground. Within the mound is a chambered passage, which may be accessed by an entrance on the southeastern side of the monument. The passage stretches for 19 metres (60 ft),[11] or about a third of the way into the centre of the structure. At the end of the passage are three small chambers off a larger central chamber with a high corbelled vault roof. Each of the smaller chambers has a large flat "basin stone" where the bones of the dead may have been deposited during prehistoric times. Whether it was a burial site remains unclear. The walls of this passage are made up of large stone slabs called orthostats, twenty-two of which are on the western side and twenty-one on the eastern side. They average 1½ metres in height;[12] several are decorated with carvings (as well as graffiti from the period after the rediscovery). The orthostats decrease in height the further into the passageway as a result of the passage being slightly graded from being constructed on the rise of a hill.[13] The ceiling shows no evidence of smoke.

Situated around the perimeter of the mound is a circle of standing stones. Twelve standing-stones survive out of a possible original thirty-five or thereabouts. Most archaeologists suggest that they were added later, during the Bronze Age, centuries after the original monument had been abandoned as a ritual centre.

Art

Newgrange contains various examples of graphic Neolithic rock art carved onto its stone surfaces.[14] These carvings fit into ten categories, five of which are curvilinear (circles, spirals, arcs, serpentiniforms, and dot-in-circles) and the other five of which are rectilinear (chevrons, lozenges, radials, parallel lines, and offsets). They are marked by wide differences in style, the skill-level needed to produce them, and on how deeply carved they are.[15] One of the most notable types of art at Newgrange are the triskele-like features found on the entrance stone. It is approximately three metres long and 1.2 metres high (10 ft long and 4 ft high), and about five tonnes in weight. It has been described as "one of the most famous stones in the entire repertory of megalithic art."[16] Archaeologists believe that most of the carvings were produced prior to the stones being erected, although the entrance stone was carved in situ before the kerbstones were placed alongside it.[17]

Various archaeologists have speculated as to the meanings of the designs, with some, such as George Coffey (in the 1890s), believing them to be purely decorative, whilst others, such as O'Kelly, believed them to have some sort of symbolic purpose, because some of the carvings had been in places that would not have been visible, such as at the bottom of the orthostatic slabs below ground level.[18] Extensive research on how the art relates to alignments and astronomy in the Boyne Valley complex was carried out by American-Irish researcher, Martin Brennan.

Cross section sketch of the passage and chamber.

Cross section sketch of the passage and chamber. The entrance passage and entrance stone (note: the grey stone wall is neither original nor reconstructed, but built for visitor access).

The entrance passage and entrance stone (note: the grey stone wall is neither original nor reconstructed, but built for visitor access). Megalithic art on one of the kerbstones.

Megalithic art on one of the kerbstones. The retaining wall and kerbstones.

The retaining wall and kerbstones.

Early history

The Neolithic people who built the monument were native agriculturalists, growing crops and raising animals such as cattle in the area where their settlements were located.

Construction and burials

The original complex of Newgrange was built between c. 3200 and 3100 BC.[19] According to carbon-14 dates,[20] it is approximately five hundred years older than the current form of Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, as well as predating the Mycenaean culture of ancient Greece.[21] Some put its period of construction somewhat later, at 3000 to 2500 BC.[22] Geological analysis indicates that the thousands of pebbles that make up the cairn, which together would have weighed about 200,000 tonnes, came from the nearby river terraces of the Boyne. There is a large pond in this area that is believed to be the site quarried for the pebbles by the builders of Newgrange.[23] Most of the 547 slabs that make up the inner passage, chambers, and the outer kerbstones are greywacke. Some or all of them may have been brought from sites approximately 5 km away,[24] from the rocky beach at Clogherhead, County Louth, about 20 km to the northeast. The facade and entrance were built with white quartz cobblestones from the Wicklow Mountains, about 50 km to the south; dark rounded granodiorite cobbles from the Mourne Mountains, about 50 km to the north; dark gabbro cobbles from the Cooley Mountains; and banded siltstone from the shore at Carlingford Lough.[24] The stones may have been transported to Newgrange by sea and up the River Boyne by fastening them to the underside of boats at low tide.[25][26] None of the structural slabs were quarried, for they show signs of having been weathered naturally, so they must have been collected and then transported, largely uphill, to the Newgrange site.[23] The granite basins found inside the chambers also came from the Mournes.[24]

Frank Mitchell suggested that the monument could have been built within a space of five years, basing his estimation upon the likely number of local inhabitants during the Neolithic and the amount of time they could have devoted to building it rather than farming. This estimate, however, was criticised by Michael J. O'Kelly and his archaeological team, who believed that it would have taken a minimum of thirty years to build.[27]

Excavations have revealed deposits of both burnt and unburnt human bone in the passage, indicating human corpses had been placed within it, some of whom had been cremated. From examining the unburnt bone, it was shown to come from at least two separate individuals, but much of their skeletons were missing, and what was left had been scattered about the passage.[28] Various grave goods were deposited alongside the bodies inside the passage. Excavations that took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s revealed seven 'marbles', four pendants, two beads, a used flint flake, a bone chisel, and fragments of bone pins and points.[29] Many more artifacts had been found in the passage in previous centuries by visiting antiquarians and tourists, although most of these were removed and went missing or held in private collections. Nonetheless, sometimes these were recorded and it is believed that the grave goods that came from Newgrange were typical of Neolithic Irish passage grave assemblages.[30] The remains of animals also have been found in the structure, primarily those of mountain hares, rabbits, and dogs, but also of bats, sheep, goats, cattle, song thrushes, and more rarely, molluscs and frogs. Most of these animals would have entered and died in the chamber many centuries or even millennia after it was constructed: for instance, rabbits were only introduced to Ireland in the thirteenth century.[31]

DNA analysis found that bones deposited in the most elaborate chamber belonged to a man whose parents were first-degree relatives, possibly brother and sister. In history, such inbreeding was usually only found in royal dynasties headed by 'god-kings', such as the pharaohs of ancient Egypt, who married among themselves to keep the royal bloodline 'pure'. This, together with the prestige of the burial, could mean that a similar elite group were responsible for building Newgrange. The man was distantly related to people buried in the Carrowkeel and Carrowmore tombs.[32][33] However, archaeologist Alasdair Whittle said that social difference in the Neolithic was often short-lived, speculating that an elite may have arisen temporarily in response to crisis. He suggested that Newgrange may have been a communal monument at certain times and co-opted as a personal tomb for brief periods.[34]

During much of the Neolithic period, the Newgrange area continued to be a focus of some ceremonial activity.

Purpose

There have been various debates as to its original purpose. Many archaeologists believed that the monument had religious significance of some sort or another, either as a place of worship for a "cult of the dead" or for an astronomically based faith. O'Kelly believed that the monument had to be seen in relation to the nearby Knowth and Dowth, and that the building of Newgrange "cannot be regarded as other than the expression of some kind of powerful force or motivation, brought to the extremes of aggrandizement in these three monuments, the cathedrals of the megalithic religion."[35] O'Kelly believed that Newgrange, alongside the hundreds of other passage tombs built in Ireland during the Neolithic, showed evidence for a religion that venerated the dead as one of its core principles. He believed that this "cult of the dead" was just one particular form of European Neolithic religion, and that other megalithic monuments displayed evidence for different religious beliefs that were solar-oriented, rather than ancestor-oriented.[35]

Studies in other fields of expertise offer alternative interpretations of the possible functions, however, which principally centre on the astronomy, engineering, geometry, and mythology associated with the Boyne monuments. It is speculated that the sun formed an important part of the religious beliefs of the Neolithic people who built it. One idea was that the room was designed for a ritualistic capturing of sun rays on the shortest day of the year, the Winter Solstice, as the room gets flooded with sunlight, which might have signaled that the days would start to get longer again. This view is strengthened by the discovery of alignments in Knowth, Dowth, and the Lough Crew Cairns leading to the interpretation of these monuments as calendrical or astronomical devices.

Formerly, the Newgrange mound was encircled by an outer ring of immense standing stones, of which twelve of a possible thirty-seven remain. Evidence from carbon dating suggests that the stone circle which encircled Newgrange may not be contemporary with the monument however, but was placed there some 1,000 years later in the Bronze Age. This view is disputed and relates to a carbon date from a standing stone setting that intersects with a later timber post circle, the theory being, that the stone in question could have been moved and later, re-set in its original position. This research implies a continuity of use of Newgrange of over a thousand years; with partial remains found from only five individuals, some question the tomb theory for its purpose. In June 2020, evidence of incest from the remains of a body buried in Newgrange was found. This led to speculation that incest may have been carried out to maintain a "dynastic bloodline", thus pointing to Newgrange as a tomb for the elites.[36]

Once a year, at the Winter Solstice, the rising sun shines directly along the long passage, illuminating the inner chamber and revealing the carvings inside, notably the triple spiral on the front wall of the chamber. This illumination lasts for approximately 17 minutes.[5] Michael J. O'Kelly was the first person in modern times to observe this event on 21 December 1967.[37] The sunlight enters the passage through a specially contrived opening, known as a roofbox, directly above the main entrance. Although solar alignments are not uncommon among passage graves, Newgrange is one of few to contain the additional roofbox feature. (Cairn G at Carrowkeel Megalithic Cemetery is another, and it has been suggested that one can be found at Bryn Celli Ddu.[38]) The alignment is such that although the roofbox is above the passage entrance, the light hits the floor of the inner chamber. Today the first light enters about four minutes after sunrise and strikes the middle of the chamber, but calculations based on the precession of the Earth show that 5,000 years ago, first light would have entered exactly at sunrise and shone on the chamber's back wall.[39] The solar alignment at Newgrange is very precise compared to similar phenomena at other passage graves such as Dowth or Maes Howe in the Orkney Islands, off the coast of Scotland.

Bronze Age and Iron Age

.JPG.webp)

By the onset of the Bronze Age, it appears that Newgrange was no longer being used by the local population, who did not leave any artifacts in the structure or bury their dead there. O'Kelly stated, "by 2000 [BC] Newgrange was in decay and squatters were living around its collapsing edge".[40] These people were adherents of the Beaker culture, which had been imported from mainland Europe, and made Beaker-style pottery locally.[40] A large timber circle (or henge) was built to the southeast of the main mound and a smaller timber circle to the west. The eastern timber circle consisted of five concentric rows of pits. The outer row contained wooden posts. The next row of pits had clay linings and was used to burn animal remains. The three inner rows of pits were dug to accept the animal remains. Within the circle were post and stake holes associated with Beaker pottery and flint flakes. The western timber circle consisted of two concentric rows of parallel postholes and pits defining a circle 20 metres (66 ft) in diameter. A concentric mound of clay was constructed around the southern and western sides of the mound that covered a structure consisting of two parallel lines of post and ditches that had been partly burnt. A free-standing circle of large stones was raised around the Newgrange mound. Near the entrance, seventeen hearths were used to set fires. These structures at Newgrange are generally contemporary with a number of henges known from the Boyne Valley, at Newgrange Site A, Newgrange Site O, Dowth Henge, and Monknewtown Henge.

The site evidently continued to have some ritual significance into the Iron Age. Among various objects later deposited around the mound are two pendants made from gold Roman coins of 320–337 AD (now in the National Museum of Ireland) and Roman gold jewellery including two bracelets, two finger rings, and a necklace, now in the collections of the British Museum.[41]

Mythology

In Irish mythology, Newgrange is often called Síd in Broga (modern Sídhe an Brugha or Sí an Bhrú). Like other passage tombs, it is described as a portal to the Otherworld and a dwelling of the divine Tuatha Dé Danann.[42]

In one tale the Dagda, the chief god, desires Boann, the goddess of the River Boyne. She lives at Brú na Bóinne with her husband Elcmar. The Dagda impregnates her after sending Elcmar away on a one-day errand. To hide the pregnancy from Elcmar, the Dagda casts a spell on him, making "the sun stand still" so he will not notice the passing of time. Meanwhile, Boann gives birth to Aengus, who is also known as Maccán Óg ('the young son'). Eventually, Aengus learns that the Dagda is his true father and asks him for a portion of land. In some versions of the tale, the Dagda helps Aengus take ownership of the Brú from Elcmar. Aengus asks to have the Brú for "a day and night", but then claims it forever, because all time is made up of "day and night". Other versions have Aengus taking over the Brú from the Dagda himself by using the same trick.[43][44] The Brú is then named Brug maic ind Óig after him. In The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne, Aengus takes Diarmuid's body to the Brú.[45]

It has been suggested that this tale represents the winter solstice illumination of Newgrange, during which the sunbeam (the Dagda) enters the inner chamber (the womb of Boann) when the sun's path stands still. The word solstice (Irish grianstad) means sun-standstill. The conception of Aengus may represent the 'rebirth' of the sun at the winter solstice, him taking over the Brú from an older god representing the growing sun taking over from the waning sun.[46] This could mean that knowledge of the event survived for thousands of years before being recorded as a myth in the Middle Ages.[44] John Carey, an expert on Irish mythology, says that the tales of Brú na Bóinne are the only Irish legends where a sacred site is linked with the control of time.[44]

There is a similar tale about Dowth (Dubhadh), one of the other Boyne Valley tombs. It tells how king Bresal compels the men of Ireland to build a tower to heaven within a day. His sister casts a spell, making the sun stand still so that one day lasts indefinitely. However, Bresal commits incest with his sister, which breaks the spell. The sun sets and the builders leave, hence the name Dubhadh ('darkening').[47] This tale has also been linked with recent DNA analysis, which found that a man buried at Newgrange had parents who were most likely siblings (see #Construction and burials).[48] Other myths reveal the acceptance, prevalence and prestige of close consanguineous unions among the divine royalty of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the mythologically nominated builders and users of Newgrange.[49]

Local folklore about Newgrange survived into the modern era.[50]

Modern history

Sometime after 1142 the structure became part of outlying farmland owned by the Cistercian Abbey of Mellifont. These farms were referred to as 'granges'. Newgrange is not mentioned in any of the early charters of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but an Inspeximus granted by Edward III in 1348 includes a Nova Grangia among the demesne lands of the abbey.[51] On 23 July 1539, following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII, Mellifont Abbey and its demesnes became the fortified mansion of an English soldier of fortune, Edward Moore, ancestor of the Earls of Drogheda.[52] On 14 August 1699, Alice Moore, Countess Dowager of Drogheda, leased the demesne of Newgrange to a Williamite settler, Charles Campbell, for 99 years.[53]

Antiquarianism in the 17th and 18th centuries

In 1699, a local landowner, Charles Campbell, ordered some of his farm labourers to dig up a part of Newgrange, which then had the appearance of a large mound of earth, so that he could collect stone from within it. The labourers soon discovered the entrance to the tomb within the mound, and a Welsh antiquarian named Edward Lhwyd, who was staying in the area, was alerted and took an interest in the monument. He wrote an account of the mound and its tomb, describing what he saw as its "barbarous sculpture" and noting that animal bones, beads, and pieces of glass had been found inside of it (modern archaeologists have speculated that these latter two were in fact the polished pottery beads that subsequently have been found at the site and that were a common feature of Neolithic tombs).[54] Soon another antiquarian visitor, Sir Thomas Molyneaux, professor at the University of Dublin, also came to the site. He talked to Charles Campbell, who informed him that he had found the remains of two human corpses in the tomb, one (which was male) in one of the cisterns and another farther along the passageway, something that Lhwyd had not noted.[55] Subsequently, Newgrange was visited by a number of antiquarians, who often performed their own measurements of the site and made their own observations, which often were published in various antiquarian journals; these included such figures as Sir William Wilde, Thomas Pownall, Thomas Wright, John O'Donovan, George Petrie, and James Ferguson.[56]

These antiquarians often concocted their own theories about the origins of Newgrange, many of which have since been proved incorrect. Thomas Pownall conducted a very detailed survey of New Grange in 1769,[57] which numbers all the stones and also records some of the carvings on the stone and asserted that the mound originally had been taller and a lot of the stone on top of it had been removed, a theory that has been disproven by archaeological research.[58] The majority of these antiquarians also refused to believe that it was ancient peoples native to Ireland who built the monument, with many believing that it had been built in the early medieval period by invading Vikings, whilst others speculated that it had been built by the ancient Egyptians, ancient Indians, or the Phoenicians.[59]

Conservation, archaeological investigation and reconstruction

.jpg.webp)

At some time in the early 1800s, a folly was built a few yards behind Newgrange. The folly, with two circular windows, was made of stones taken from Newgrange. In 1882, under the Ancient Monuments Protection Act, Newgrange and the nearby monuments of Knowth and Dowth were placed under the control of the state with the Board of Public Works being the responsible administrative authority. In 1890, under the leadership of Thomas Newenham Deane, the board began a project of conservation of the monument, which had been damaged through general deterioration over the previous three millennia as well as the increasing vandalism caused by visitors, some of whom had inscribed their names on the stones.[60] In subsequent decades, a number of archaeologists performed excavations at the site, discovering more about its function and how it had been built; however, even at the time, it was still mistakenly believed by archaeologists to be built during the Bronze Age rather than during the earlier Neolithic period.[61] In the 1950s, electric lighting was installed in the passageway to allow visitors to see more clearly,[62] whilst an exhaustive archaeological excavation was undertaken from 1962 through to 1975, the excavation report of which was written by Michael J. O'Kelly and published in 1982 by Thames and Hudson as Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend.[63]

Following the O'Kelly excavation, further restoration and reconstruction took place at the site. Based on the positions of the cobblestones, and after conducting experiments, O'Kelly concluded that they had made up a retaining wall, but had fallen from the face of the mound. As part of the restoration, this wall was "rebuilt" and the cobblestones were fixed into a near-vertical steel-reinforced concrete wall surrounding the front of the mound. This work is controversial among the archaeological community. P. R. Giot described the monument as looking like a "cream cheese cake with dried currants distributed about."[64] Neil Oliver described the reconstruction as "a bit brutal, a bit overdone, kind of like Stalin does the Stone Age".[65] Critics of the new wall claim that the technology to fix a retaining wall at this angle did not exist when the mound was created.[66][67]

Another theory is that some, or all, of the white quartz cobblestones had formed a plaza on the ground at the entrance. This theory was preferred at nearby Knowth, where the restorers laid the quartz stones out as an "apron" in front of the entrance to the great mound.[68]

The inward-curving dark stone walls on each side of the entrance are not original, nor are they intended to suggest Newgrange's original appearance, but were designed solely to facilitate visitor access. A visitor guide book to the site, however, has a reconstruction drawing depicting Neolithic inhabitants using Newgrange that shows the modern entrance as if it were part of Newgrange's original appearance.[69]

The culture that built Newgrange is sometimes confused with the much later Celtic culture, and designs on the stones are misdescribed as "Celtic".[70] However, recent archaeogenetics suggests that the west European neolithic population was largely replaced by later arrivals.[71]

Access

Newgrange is located 8.4 kilometres (5.2 mi) west of Drogheda in County Meath. The interpretive centre is located on the south bank of the river and Newgrange is located on the north side of the river. Access is only from the interpretive centre.

Access to Newgrange is by guided tour only. Tours begin at the Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre from which visitors are taken to the site in groups.[72] Current-day visitors to Newgrange are treated to a guided tour and an re-enactment of the Winter Solstice experience through the use of high-powered electric lights situated within the tomb. The finale of a Newgrange tour results in every visitor standing inside the tomb where the tour guide then turns off the lights, and then turns on ones simulating the sunlight that would appear on the winter solstice.

To experience the phenomenon on the morning of the Winter Solstice from inside Newgrange, visitors to Bru Na Bóinne Visitor Centre must enter an annual lottery at the centre. Of the tens of thousands who enter, sixty are chosen each year. Winners are permitted to bring a single guest. The winners are split into groups of ten and taken in on the five days around the solstice in December when sunlight can enter the chamber, weather permitting.[73] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the 2020 and 2021 events were exclusively live-streamed with no public access.[74]

Gallery

Decorated and cracked roof stone of the east side-chamber

Decorated and cracked roof stone of the east side-chamber Triskele (triple spiral) pattern on orthostat C10 in the end-chamber

Triskele (triple spiral) pattern on orthostat C10 in the end-chamber A chiselled granite basin in the east side-chamber

A chiselled granite basin in the east side-chamber

References

- "Sí an Bhrú /Newgrange". logainm.ie. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- O'Kelly, Michael J. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 13.

- Lynch, Ann (2014). "Newgrange revisited: New insights from excavations at the back of the mound in 1984–8". The Journal of Irish Archaeology. 23: 13–82 – via JSTOR.

- Carrowkeel Cairn G. The Megalithic Portal.

- "The Winter Solstice Illumination of Newgrange". Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- O'Kelly and O'Kelly, 102

- Laing 1974, p. 42

- "Newgrange got new lease of light and life in 1960s 'rebuild'". The Irish Times. 20 December 2008.

- Renfrew, Colin, in O'Kelly, Michael J. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 7.

- Hensey (2015). First Light: The origins of Newgrange. Oxbow Books. p. 13.

- "Newgrange". newgrange.com. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- O'Kelly (1982:21)

- Hensey, Robert (2017). Papadopoulos, Costas; Moyes, Holley (eds.). "Rediscovering the winter solstice alignment at Newgrange, Ireland". The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology: 140–163. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198788218.013.5. ISBN 978-0-19-878821-8.

- Joseph Nechvatal, Immersive Ideals / Critical Distances. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 2009, p. 163

- O'Kelly (1982:146–147).

- Ó Ríordáin, Seán P.; Glyn, Edmund Daniel (1964). New Grange and the Bend of the Boyne. F.A. Praeger. p. 26.

- O'Kelly (1982:149).

- O'Kelly (1982:148).

- "Newgrange". Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- E. Grogan, "Prehistoric and Early Historic Cultural Change at Brugh na Bóinne", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 91C, 1991, pp. 126–132

- O'Kelly (1982:48)

- Grant, Jim; Sam Gorin; Neil Fleming (2008). The archaeology coursebook. Taylor & Francis. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-415-46286-0. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- O'Kelly (1982:117)

- Tilley, Christopher. Body and Image: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology. Left Coast Press, 2008. p.160

- Benozzo, F. (2010). "Words as Archaeological Finds: A Further Example of the Ethno-Philological Contribute to the Study of European Megalithism". The European Archaeologist. 33: 7–10.

- Phillips, W.E.A.; M. Corcoran; E. Eogan (2001), Identification of the source area for megaliths used in the construction of the Neolithic passage graves of the Boyne Valley, Co. Meath. Unpublished report for the Heritage Council., Department of Geology, Trinity College Dublin, archived from the original on 12 December 2011, retrieved 29 November 2011

- O'Kelly (1982:117–118)

- O'Kelly (1982:105–106)

- O'Kelly (1982:105)

- O'Kelly (1982:107)

- O'Kelly (1982:215–216)

- Cassidy, Lara M.; Maoldúin, Ros Ó; Kador, Thomas; Lynch, Ann; Jones, Carleton; Woodman, Peter C.; Murphy, Eileen; Ramsey, Greer; Dowd, Marion; Noonan, Alice; Campbell, Ciarán (18 June 2020). "A dynastic elite in monumental Neolithic society". Nature. 582 (7812): 384–388. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..384C. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2378-6. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7116870. PMID 32555485. S2CID 219729757.

- "DNA study reveals Ireland's age of 'god-kings'". BBC News, 17 June 2020.

- "DNA from ancient Irish tomb reveals incest and an elite class that ruled early farmers". Science, 17 June 2020.

- O'Kelly (1982:122)

- Sheridan, Alison (17 June 2020). "Incest Uncovered at the Elite Prehistoric Newgrange Monument in Ireland". Nature. 582 (7812): 347–349. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..347S. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01655-4. PMID 32555481.

- "Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth)". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- Pitts (2006) Sensational new discoveries at Bryn Celli Ddu. British Archaeology No. 89 (July/August): 6.

- Ray, T. P. (January 1989). "The winter solstice phenomenon at Newgrange, Ireland: accident or design?". Nature. 337 (6205): 343–345. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..343R. doi:10.1038/337343a0. S2CID 4349872.

- O'Kelly (1982:145).

- "British Museum – Collection search". British Museum. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Löffler, Christa. The Voyage to the Otherworld Island in Early Irish Literature. Brill Academic Publishers, 1983. pp.81-82

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p.39

- Hensey, Robert. Re-discovering the winter solstice alignment at Newgrange, in The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology. Oxford University Press, 2017. pp.11-13

- O'Kelly (1982:43–46)

- Anthony Murphy and Richard Moore. "Chapter 8, Newgrange: Womb of the Moon", Island of the Setting Sun: In Search of Ireland's Ancient Astronomers. Liffey Press, 2008. pp.160-172

- Koch, John. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2006. p.619

- "Stone Age ruling elite in Ireland may have had incestuous marriages". New Scientist, 17 June 2020.

- Graham, Lloyd D. (26 August 2021). "Consanguineous unions in the archaeology and mythology of the Neolithic passage-tomb at Newgrange, Ireland". Academia Letters: 2963. doi:10.20935/AL2963.

- "Cuardach téacs". dúchas.ie (in Ga). Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "An Important Mellifont Document." Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, vol. 14, no. 1, 1957, pp. 1–13.

- Geraldine Stout, Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne, Cork University Press, Cork (2002), pp. 85, 102

- Stout (2002:128)

- O'Kelly (1982:24)

- O'Kelly (1982:27)

- O'Kelly (1982:33–34)

- Archaeologia Vol 2, 1773. A Description of the Sepulchral Monument of New Grange, near Drogheda, in the County of Meath, in Ireland. By Thomas Pownall, Esq. in a letter to the Rev. Gregory Sharpe, D.D. Master of the Middle Temple. Read at the Society of Antiquaries, 21/28 June 1770. Archaeologia Vol 2, pp. 236–276

- O'Kelly (1982:33)

- O'Kelly (1982:35)

- O'Kelly (1982:38–39)

- O'Kelly (1982:42)

- O'Kelly (1982:41)

- O'Kelly (1982:09)

- Giot, P.-R. (1983). "Review: Newgrange: archaeology, art and legend". Antiquity. 57 (220): 150.

- "A History of Ancient Britain" Series 1 episode 3, "Age of Cosmology", BBC documentary, 2011.

- Eriksen, Palle (2008). "The Great Mound of Newgrange, An Irish Multi-Period Mound Spanning from the Megalithic Tomb Period to the Early Bronze Age". Acta Archaeologica. 79 (1): 250–273. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0390.2008.00118.x.

- Eriksen, Palle (September 2006). "The Rolling Stones of Newgrange". Antiquity. 80 (309): 709–710. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00094151. S2CID 162640314.

- May, Jeffrey (October 2003). "Knowth Excavations". Current Archaeology. 188. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Alan Marshall, "Newgrange Excavation Report Critique"

- "History of Newgrange Stone Age Passage Tomb in Ireland". 21 March 2010.

- Reich D. Who we are and how we got here; Oxford UP (2018) pp. 98, 114–117.

- Heritage Ireland

- "Winter Solstice | Brú na Bóinne | World Heritage | World Heritage Ireland". worldheritageireland.ie. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Winter Solstice at Newgrange 2020".

External links

- Official website

- Information on Newgrange by Meath Tourism

- Irish passage tombs and other Neolithic monuments

- 101 Facts About Newgrange

- Newgrange.eu

- Windows Media recording of the 2007 Winter Solstice event

- Short Video by National Geographic about Newgrange.

- MegalithicIreland.com

- Brú na Bóinne in myth and folklore

- Newgrange winter solstice simulation in 3D

- Calendrical Interpretation of Spirals in Irish Megalithic Art on Arxiv.org 19 March 2019.

- Here Comes the Sun Neil MacGregor narrates a BBC Radio 4 / British Museum programme describes the solstice at Newgrange, making a comparison with the story of Amaterasu, Japanese sun goddess. (May 2022)