Norman Lear

Norman Milton Lear (born July 27, 1922) is an American television screenwriter, film and television producer who has produced, written, created, or developed over 100 shows.[1] Lear is known for many popular 1970s sitcoms, including the multi-award winning All in the Family as well as Maude, Sanford and Son, One Day at a Time, The Jeffersons, and Good Times.

Norman Lear | |

|---|---|

Lear receiving the 2017 Kennedy Center Honors | |

| Born | Norman Milton Lear July 27, 1922 New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Television producer, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1948–present |

| Known for | Sitcoms: All in the Family The Jeffersons Sanford and Son Good Times Maude Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman One Day at a Time |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 6 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | Technical sergeant |

| Unit | 463rd Bombardment Group Fifteenth Air Force |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Website | normanlear |

Lear has continued to actively produce television, including the 2017 remake of One Day at a Time and the Netflix revival of Good Times in 2022.[2]

Lear has received many awards, including five Emmys, the National Medal of Arts, and the Kennedy Center Honors. He is a member of the Television Academy Hall of Fame. Lear is also known for his political activism and funding of liberal and progressive causes and politicians. In 1980, he founded the advocacy organization People for the American Way to counter the influence of the Christian right in politics, and in the early 2000s, he mounted a tour with a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

Early life

Lear was born in New Haven, Connecticut,[3][4] the son of Jeanette (née Seicol) and Hyman "Herman" Lear, a traveling salesman.[4] He had a younger sister, Claire Lear Brown (1925–2015).[5] Lear grew up in a Jewish household in Connecticut and had a Bar Mitzvah ceremony.[6] His mother was originally from Ukraine, while his father's family was from Russia.[7][8][9]

When Lear was nine years old and living with his family in Chelsea, Massachusetts,[10] his father went to prison for selling fake bonds.[11] Lear thought of his father as a "rascal" and said that the character of Archie Bunker (whom Lear depicted as white Protestant on the show) was in part inspired by his father, while the character of Edith Bunker was in part inspired by his mother.[11] However, Lear has said the moment which inspired his lifetime of advocacy was another event which he experienced at the age of nine, when he first came across infamous anti-semitic Catholic radio priest Father Charles Coughlin while tinkering with his crystal radio set.[12] Lear has also said he would hear more of Coughlin's radio sermons over time, and found out that Coughlin would at times find different ways to promote anti-semitism by also targeting people whom Jews considered to be "great heroes," such as US President Franklin Roosevelt.[13]

Lear graduated from Weaver High School in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1940 and attended Emerson College in Boston, but dropped out in 1942 to join the United States Army Air Forces.[14]

Lear enlisted in the United States Army in September 1942.[15] He served in the Mediterranean theater as a radio operator/gunner on Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers with the 772nd Bomb Squadron, 463rd Bomb Group of the Fifteenth Air Force; he also has talked about bombing Germany in the European theater.[11] Lear flew 52 combat missions and was awarded the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters. Lear was discharged from the Army in 1945, and his fellow World War II crew members are featured in the books Crew Umbriago, by Daniel P. Carroll (tail gunner), and 772nd Bomb Squadron: The Men, The Memories, by Turner Publishing and Co.

Career

After World War II Lear had a career in public relations.[11] The career choice was inspired by his Uncle Jack: "My dad had a brother, Jack, who flipped me a quarter every time he saw me. He was a press agent so I wanted to be a press agent. That's the only role model I had. So all I wanted was to grow up to be a guy who could flip a quarter to a nephew."[6] Lear decided to move to California to restart his career in publicity, driving with his toddler daughter across the country.[11]

His first night in Los Angeles, Lear stumbled upon a production of George Bernard Shaw's Major Barbara at the 90-seat theater-in-the-round Circle Theater off Sunset Boulevard. One of the actors in the play was Sydney Chaplin, the son of actors Charlie Chaplin and Lita Grey. Charlie Chaplin, Alan Mowbray, and Dame Gladys Cooper sat in front of Lear, and after the show was over, Charlie Chaplin performed.[11]

Lear had a first cousin in Los Angeles, Elaine, who was married to an aspiring comedy writer called Ed Simmons. Simmons and Lear teamed up to sell home furnishings door-to-door for a company called The Gans Brothers and later sold family photos door-to-door. Throughout the 1950s, Lear and Simmons turned out comedy sketches for television appearances of Martin and Lewis, Rowan and Martin, and others. They frequently wrote for Martin and Lewis when they appeared on the Colgate Comedy Hour and a 1953 article from Billboard magazine stated that Lear and Simmons were guaranteed a record-breaking $52,000 each to write for five additional Martin and Lewis appearances on the Colgate Comedy Hour that year.[16] In a 2015 interview with Vanity Magazine, Lear said that Jerry Lewis had hired him and Simmons as writers for Martin and Lewis three weeks before the comedy duo made their first appearance on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1950.[17] Lear also acknowledged in 1986 that he and Simmons were the main writers for The Martin and Lewis Show for three years.[18]

In 1954, Lear was enlisted as a writer and asked to salvage the new CBS sitcom starring Celeste Holm, Honestly, Celeste!, but the program was canceled after eight episodes. During this time he became the producer of NBC's short-lived (26 episodes) sitcom The Martha Raye Show, after Nat Hiken left as the series director. Lear also wrote some of the opening monologues for The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show[17][19] which aired from 1956 to 1961. In 1959, Lear created his first television series, a half-hour western for Revue Studios called The Deputy, starring Henry Fonda.

1970s

Starting out as a comedy writer, then a film director (he wrote and produced the 1967 film Divorce American Style and directed the 1971 film Cold Turkey, both starring Dick Van Dyke), Lear tried to sell a concept for a sitcom about a blue-collar American family to ABC. They rejected the show after two pilots were taped: "Justice for All" in 1968[20] and "Those Were the Days" in 1969.[21] After a third pilot was taped, CBS picked up the show, known as All in the Family. It premiered January 12, 1971, to disappointing ratings, but it took home several Emmy Awards that year, including Outstanding Comedy Series. The show did very well in summer reruns,[22] and it flourished in the 1971–72 season, becoming the top-rated show on TV for the next five years.[23] After falling from the #1 spot, All in the Family still remained in the top ten, well after it became Archie Bunker's Place. The show was based loosely on the British sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, about an irascible working-class Tory and his socialist son-in-law.[24]

Lear's second big TV sitcom, Sanford and Son, was also based on a British sitcom, Steptoe and Son,[25] about a west London junk dealer and his son. Lear changed the setting to the Watts section of Los Angeles and the characters to African-Americans, and the NBC show Sanford and Son was an instant hit. Numerous hit shows followed thereafter, including Maude, The Jeffersons (as with Maude a spin-off of All in the Family), One Day at a Time, and Good Times (which was a spinoff of Maude).[26]

Most of these Lear sitcoms shared three features; they were shot on videotape in place of film, used a live studio audience, and dealt with the social and political issues of the day.[27] Maude is generally considered to be based on Lear's wife Frances, something she herself confirmed, with Charlie Hauck serving as main producer and writer.[28][29]

Lear's longtime producing partner was Bud Yorkin, who also produced All in the Family, Sanford and Son, What's Happening!!, Maude, and The Jeffersons.[30] Yorkin split with Lear in 1975. He started a production company with writer/producers Saul Turteltaub and Bernie Orenstein; however only two of their shows lasted longer than a year: What's Happening!! and Carter Country. The Lear/Yorkin company was known as Tandem Productions and was founded in 1958. Lear and talent agent Jerry Perenchio founded T.A.T. Communications ("T.A.T." stood for the Yiddish phrase "Tuchus Affen Tisch", which meant "Putting one's ass on the line."[31]) in 1974, which co-existed with Tandem Productions and was often referred to in periodicals as Tandem/T.A.T. The Lear organization was one of the most successful independent TV producers of the 1970s. TAT produced the influential and award-winning 1981 film The Wave about Ron Jones' social experiment.

Lear also developed the cult favorite TV series Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman (MH MH) which was turned down by the networks as "too controversial" and placed it into first run syndication with 128 stations in January 1976. A year later, Lear added another program into first-run syndication along with MH MH, All That Glitters. He planned in 1977 to offer three hours of prime-time Saturday programming directly having stations place his production company in the position of an occasional network.[17][32]

In 1977, African American screenwriter Eric Monte filed a lawsuit accusing ABC and CBS producers Norman Lear, Bud Yorkin, and others of stealing his ideas for Good Times, The Jeffersons, and What's Happening!! Monte received a $1-million settlement and a small percentage of the residuals from Good Times and one percent ownership of the show. Monte, due to his lack of business knowledge and experience as well as legal representation, would not receive royalties for other shows which he created. However, Lear and other Hollywood producers, outraged over the lawsuit, blacklisted Eric Monte and labeled him too difficult to work with.[33]

1980s and 1990s

In 1980, Lear founded the organization People for the American Way for the purpose of counteracting the Christian right group Moral Majority which haf bern founded in 1979.[34] In the fall of 1981, Lear began a 14-month run as the host of a revival of the classic game show Quiz Kids for the CBS Cable Network. In January 1982, Lear and Jerry Perenchio bought Avco Embassy Pictures from Avco Financial Corporation. In January 1982, after merging with company with T.A.T. Communications, the Avco was dropped, and the combined entity was renamed as Embassy Communications, Inc.[35] Embassy Pictures was led by Alan Horn and Martin Schaeffer, later co-founders of Castle Rock Entertainment with Rob Reiner.

In March 1982, Lear produced an ABC television special titled I Love Liberty, as a counterbalance to the infomagroups like the Moral Majority.[36] Among the many guests who appeared on the special was conservative icon and the 1964 U.S. presidential election's Republican nominee Barry Goldwater.[36]

On June 18, 1985, Lear and Perenchio sold Embassy Communications to Columbia Pictures (then owned by the Coca-Cola Company), which acquired Embassy's film and television division (including Embassy's in-house television productions and the television rights to the Embassy theatrical library) for $485 million of shares of The Coca-Cola Company.[37][38] Lear and Perenchio split the net proceeds (about $250 million). Coca-Cola later sold the film division to Dino De Laurentiis and the home video arm to Nelson Holdings (led by Barry Spikings).

The brand Tandem Productions was abandoned in 1986 with the cancellation of Diff'rent Strokes, and Embassy ceased to exist as a single entity in late 1986, having been split into different components owned by different entities.[39] The Embassy TV division became ELP Communications in 1988, but shows originally produced by Embassy were now under the Columbia Pictures Television banner from 1988 to 1996 and the Columbia TriStar Television banner from 1996 to 2002.

Lear's Act III Communications was founded in 1986 and in the following year, Thomas B. McGrath was named president and chief operating officer of ACT III Communications Inc after previously serving as senior vice president.[40][41] On February 2, 1989, Norman Lear's Act III Communications formed a joint venture with Columbia Pictures Television called Act III Television to produce television series instead of managing.[42][43]

In 1997, Lear and Jim George produced the Kids' WB series Channel Umptee-3. The cartoon was the first to meet the Federal Communications Commission's then-new educational programming requirements.[44]

2000s and 2010s

In 2003, Lear appeared on South Park during the "I'm a Little Bit Country" episode, providing the voice of Benjamin Franklin. He also served as a consultant on the episodes "I'm a Little Bit Country" and "Cancelled". Lear has attended a South Park writers' retreat,[45] and was the officiant at co-creator Trey Parker's wedding.[46]

Lear is spotlighted in the 2016 documentary Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You.[47] In 2017, Lear served as executive producer for One Day at a Time, the reboot of his 1975-1984 show of the same name that premiered on Netflix starring Justina Machado and Rita Moreno as a Cuban-American family. He has hosted a podcast, All of the Above with Norman Lear, since May 1, 2017.[48][49] On July 29, 2019, it was announced that Lear had teamed with Lin-Manuel Miranda to make an American Masters documentary about Moreno's life, tentatively titled Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided to Go for It.[50] In 2020, it was announced that Lear and Act III Productions would executive produce a revival of Who’s The Boss?[51]

In 2014, Lear published Even This I Get To Experience, a memoir.[52]

Awards and nominations

| Institution | Award | Year | Work/s | Results |

| Academy Awards | Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay | 1967 | Divorce American Style | Nominated |

| Television Academy | Hall of Fame | 1984 (as inductee) | Honoured | |

| Emmy Awards | Most Outstanding Series (comedy) | 1971 | All in the Family | Won x2 |

| Emmy Awards | 1972 | All in The Family | Won | |

| Emmy Award | 1973 | All in the Family | Won | |

| Emmy awards | Outstanding Variety (Live) Award | 2009 | Live in Front of A Live Studio Audience: Norman Lears Allin the Family and The Jeffersons | Won |

| Peabody Awards | Recipient award | 1977 | Lifetime achievement | Won |

| Peabody Awards | Individual honourary award | 2016 | Lifetime achievement | Won |

| American Humanist Association | Humanist Arts Award | 1977 | Humanitarian recognition | Won |

| Academy of Achievement | Golden Plate Award | 1980 | Won | |

| National Hispanic Media Coalition | Media Icon | 2017 | Won | |

| Brittannia Awards | Excellence in Television | 2007 | Won |

Honors

Norman Lear's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 6615 Hollywood Boulevard.[55]

In 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded the National Medal of Arts to Lear, noting, "Norman Lear has held up a mirror to American society and changed the way we look at it." Also in 1999, he and Bud Yorkin received the Women in Film Lucy Award in recognition of excellence and innovation in creative works that have enhanced the perception of women through the medium of television.[56][57]

On May 12, 2017, Lear was awarded the fourth annual Woody Guthrie Prize presented by the Woody Guthrie Center based in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[58] The event took place in the Clive Davis Theater at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles.

The Woody Guthrie Prize is given annually to an artist who exemplifies the spirit and life work of Guthrie by speaking for the less fortunate through music, literature, film, dance or other art forms and serving as a positive force for social change in America. Previous honorees include Pete Seeger, Mavis Staples and Kris Kristofferson.[59]

On August 3, 2017, it was announced that the Kennedy Center had made Lear, along with Carmen de Lavallade, Lionel Richie, LL Cool J, and Gloria Estefan, a recipient of the 2017 Kennedy Center Honors. US President Donald Trump and First Lady Melania Trump were scheduled to be seated with the honorees during the Kennedy Center ceremony, which took place on December 3, 2017, and they were planning to host a reception with them at the White House earlier in the evening. Variety magazine's senior editor Ted Johnson reacted saying "That in and of itself will be an interesting moment, as Lear and Estefan have been particularly outspoken against Trump and his policies." It was afterwards announced that Lear would boycott the White House reception.[61] In the end, the President and First Lady did not attend.[62] The Producers Guild of America instituted the Norman Lear Achievement Award in Television in his honour and he was a recipient in 2005.

Political and cultural activities

In addition to his success as a TV writer and producer, Lear is an outspoken supporter of First Amendment and liberal causes. The only time that he did not support the Democratic candidate for President was in 1980. He supported John Anderson because he considered the Carter administration to be "a complete disaster".[63]

Lear was one of the wealthy Jewish Angelenos known as the Malibu Mafia.[64] In the 1970s and 1980s, the group discussed progressive and liberal political issues, and worked together to fund them. They helped to fund the legal defense of Daniel Ellsberg who had released the Pentagon Papers,[65] and they backed the struggling progressive magazine The Nation to keep it afloat.[66] In 1975, they formed the Energy Action Committee to oppose Big Oil's powerful lobby in Washington.[65]

In 1981, Lear founded People for the American Way (PFAW), a progressive advocacy organization formed in reaction to the politics of the Christian right.[65] PFAW ran several advertising campaigns opposing the interjection of religion in politics.[67] PFAW succeeded in stopping Reagan's 1987 nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court.[68] Lear, a longtime critic of the Religious Right, is an advocate for the advancement of secularism.[69][70]

Prominent right-wing Christians including Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and Jimmy Swaggart have accused Lear of being an atheist and holding an anti-Christian bias.[69][70] In the January 21, 1987 issue of The Christian Century, Lear associate Martin E. Marty (a Lutheran professor of church history at the University of Chicago Divinity School between 1963 and 1998) rejected those allegations, stating the television producer honored religious moral values and complimenting Lear's understanding of Christianity.[70] Marty noted that while Lear and his family had never practiced Orthodox Judaism,[70] the television producer was a follower of Judaism.[70]

In a 2009 interview with US News journalist Dan Gilgoff, Lear rejected claims by right-wing Christian nationalists that he was an atheist and prejudiced against Christianity. Lear holds religious beliefs and has integrated some evangelical Christian language into his Born Again American campaign. He does believe that religion should be kept separate from politics and policymaking.[69] In a 2014 interview with The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles journalist Rob Eshman, Lear described himself as a "total Jew" but said he was never a practicing one.[71]

In 1989, Lear founded the Business Enterprise Trust, an educational program that used annual awards, business school case studies, and videos to spotlight exemplary social innovations in American business until it ended in 1998. He announced in 1992 that he was reducing his political activism.[72] In 2000, he provided an endowment for a multidisciplinary research and public policy center that explored the convergence of entertainment, commerce, and society at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. It was later named the Norman Lear Center in recognition.

Lear serves on the National Advisory Board of the Young Storytellers Foundation. He has written articles for The Huffington Post. Lear is a trustee emeritus at The Paley Center for Media.[73]

Declaration of Independence

In 2001, Lear and his wife, Lyn, purchased a Dunlap broadside—one of the first published copies of the United States Declaration of Independence—for $8.1 million. John Dunlap printed about 200 copies of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. 25 copies survive today and only four of those are in private hands; those four are promised to public collections. The others belong to city halls, public libraries, historical societies, and universities.

Not a document collector, Lear said in a press release and on the Today show that his intent was to tour the document around the United States so that the country could experience its "birth certificate" firsthand.[74] Through the end of 2004, the document traveled throughout the United States on the Declaration of Independence Roadtrip, which Lear organized, visiting several presidential libraries, dozens of museums, as well as the 2002 Olympics, Super Bowl XXXVI, and the Live 8 concert in Philadelphia. Lear and Rob Reiner produced a filmed, dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence—the last project filmed by famed cinematographer Conrad Hall—on July 4, 2001, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The film is introduced by Morgan Freeman and Kathy Bates, Benicio del Toro, Michael Douglas, Mel Gibson, Whoopi Goldberg, Graham Greene, Ming-Na Wen, Edward Norton, Winona Ryder, Kevin Spacey, and Renée Zellweger appear as readers.[75] It was directed by Arvin Brown and scored by John Williams.[76]

Declare Yourself

In 2004, Lear established Declare Yourself which is a national nonpartisan, nonprofit campaign created to empower and encourage eligible 18- to 29-year-olds in America to register and vote. It has registered almost 4 million young people.[77]

2015 Iran nuclear deal

Lear was one of 98 "prominent members of Los Angeles' Jewish community" who signed an open letter supporting the proposed nuclear agreement between Iran and six world powers led by the United States. The letter called for the passage of the bill and warned that the ending of the agreement by Congress would be a "tragic mistake".[78]

Personal life

Lear has been married three times.[14] He was married to Frances Loeb, publisher of Lear's magazine from 1956 to 1985.[79] They separated in 1983, with Loeb eventually receiving $112 million from Lear in their divorce settlement.[80] In 1987 he married his current wife, producer Lyn Davis. Lear is a godparent to actress and singer Katey Sagal.[81] On July 27, 2022, he turned 100.[82]

Appearances in popular culture

Lear plays the protagonist in the video to "Happy Birthday to Me," the first single on musician and actor Paul Hipp's 2015 album The Remote Distance.

The top of my bucket list always included a desire to sing. More than that — a desire to enchant an audience with my voice. I ached to be Sinatra or Tormé for just a night. You say a night's too much? How about just one song?" My friend, actor, singer-guitarist and composer, Paul Hipp, wrote the happy birthday song when he turned fifty. I loved it and asked if I could perform it as I turn ninety-three. That was the result, and I don't care what you say, I love it.[83]

TV productions

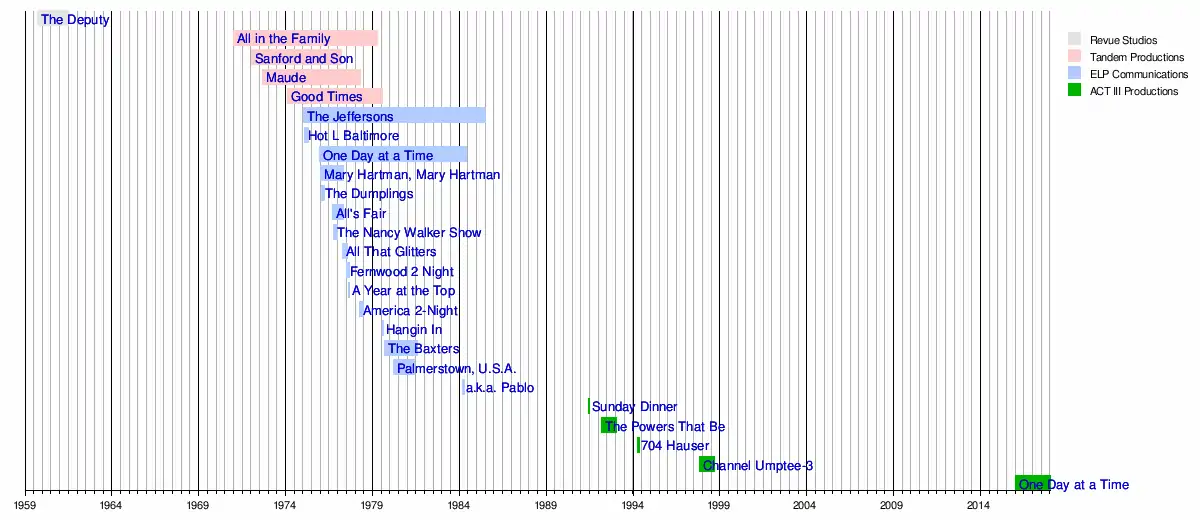

Note: The above chart does not include the made-for-television movies The Wave, which aired on October 4, 1981, or Heartsounds, which aired on September 30, 1984.

Publications

- Lear, Norman. "Liberty and Its Responsibilities". Broadcast Journalism, 1979–1981. The Eighth Alfred I. DuPont Columbia University Survey, Ed. By Marvin Barrett. New York: Everest House, 1982. ISBN 978-0-896-96160-9. OCLC 8347364.

- Lear, Norman. "Our Political Leaders Mustn't Be Evangelists", USA Today, August 17, 1984.

- Lear, Norman and Ronald Reagan. "A Debate on Religious Freedom", Harper's Magazine, October 1984.

- Lear, Norman. "Our Fragile Tower of Greed and Debt", The Washington Post, April 5, 1987.

- Lear, Norman. Even This I Get to Experience. New York: The Penguin Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-594-20572-9. OCLC 870919776.

Further reading

- Carroll, Daniel P., and Albert K. Brown. Crew Umbriago. [S.l.]: D.P. Carroll, 1986.

- Turner Publishing Co. 772nd Bomb Squadron: The Men - the Memories of the 463rd Bomb Group (The Swoose Group). Paducah, KY: Turner Pub. Co, 1996. ISBN 978-1-563-11320-8

- Campbell, Sean. The Sitcoms of Norman Lear. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co, 2007. ISBN 978-0-786-42763-5

- Just Another Version of You. PBS American Masters documentary. 2016.

- Miller Taylor Cole. Syndicated Queerness: Television Talk Shows, Rerun Syndication, and the Serials of Norman Lear. dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2017.

References

- Lear, Norman (2014). Even This I Get To Experience. Penguin. pp. preface.

- Petski, Denise (September 14, 2020). "Netflix Orders Animated Version Of Norman Lear's 'Good Times' From Lear, Steph Curry & Seth MacFarlane". Deadline. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "Norman Lear Biography: Screenwriter, Television Producer, Pilot (1922–)". Biography.com (FYI / A&E Networks). Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Norman Lear Fast Facts". CNN.

- Lynch, M.A.C. (March 12, 2006). "Their Junior High Romance Has Lasted 60 Happy Years". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "An Interview with Norman Lear". Aish HaTorah. March 6, 2001. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Norman Lear - United States Census, 1930". FamilySearch. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "Family:Herman Lear and Jeanette Seicol (1)". WeRelate. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Stated on Finding Your Roots, January 26, 2016, PBS

- Radio interview with Norman Lear, January 16 2022 archived from WGBH (FM) broadcast

- Lopate, Leonard (October 15, 2014). "Norman Lear's Storytelling, the Brooklyn Museum's Killer Heels". The Leonard Lopate Show. WNYC. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Schneider, Michael (September 17, 2019). "How Norman Lear Devoted Himself to a Lifetime of Advocacy". Variety.

- "Norman Lear: 'Just Another Version Of You'". NPR.

- "Overview for Norman Lear". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "Norman M Lear - United States World War II Army Enlistment Records". FamilySearch. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "Billboard". October 31, 1953 – via Google Books.

- Gray, Tim (October 30, 2015). "Norman Lear Looks Back on Early Days as TV Comedy Writer".

- "Writing for Early Live Television | Norman Lear | television, film, political and social activist, philanthropist".

- Sickels, Robert C. (August 8, 2013). 100 Entertainers Who Changed America: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598848311 – via Google Books.

- "Justice For All". You Tube. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- "Those Were The Days". YouTube. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Cowan, Geoffrey (March 28, 1980). See No Evil. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671254117 – via Google Books.

- Leonard, David J; Guerrero, Lisa (April 23, 2013). African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings. ISBN 9780275995157.

- Prial, Frank J. (May 12, 1983). "CBS-TV IS DROPPING ARCHIE BUNKER". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "Sanford And Son may have copied other shows, but Redd Foxx was an original". The A.V. Club. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Gray, Tim (January 12, 2021). "How 'All in the Family' Spawned the Most Spinoffs of Any Sitcom". Variety. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Weinman, Jaime (September 30, 2008). "Is It Time For Sitcoms To Go Back to Videotape?". Macleans.ca. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Nemy, Enid (October 1, 1996). "Frances Lear, a Mercurial Figure of the Media and a Magazine Founder, Dead at 73" – via NYTimes.com.

- Lee, Janet W. (November 20, 2020). "Charlie Hauck, Writer-Producer of 'Maude' and 'Frasier,' Dies at 79". Variety. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Roberts, Sam (August 19, 2015). "Bud Yorkin, Writer and Producer of 'All in the Family,' Dies at 89". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Miller, Taylor Cole (2017). "Chapter 2: Rewriting Genesis: Queering Genre in Norman Lear's First-Run Syndicated Serials". Syndicated Queerness: Television Talk Shows, Rerun Syndication, and the Serials of Norman Lear (PhD). University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Nadel, Gerry (May 30, 1977). "Who Owns Prime Time? The Threat of the 'Occasional' Networks". New York Magazine. pp. 34–35. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- Classic TV Producer, Good Times No Longer. July 29, 2006. npr.com. Retrieved on September 6, 2021.

- "Lear TV Ads to Oppose The Moral Majority". The New York Times. June 25, 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "Avco Embassy". The New York Times. January 5, 1982. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- O'Connor, John J. (March 19, 1982). "TV Weekend; LEAR'S 'I LOVE LIBERTY' LEADS SPECIALS (Published 1982)". The New York Times.

- Michael Schrage (June 18, 1985). "Coke Buys Embassy & Tandem". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- Al Delugach; Kathryn Harris (June 18, 1985). "Lear, Perenchio Sell Embassy Properties". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- Ryan, Joal (2000). Former Child Stars: The Story of America's Least Wanted. United Kingdom: ECW Press. p. 150. ISBN 9781550224283. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- "Los Angeles County". Los Angeles Times. December 12, 1987. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022.

- "Executive Changes". The New York Times. December 14, 1987. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022.

- Knoedelseder, William K. Jr. (February 2, 1989). "Norman Lear, Columbia Form Joint TV Venture". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021.

- Stevenson, Richard W. (February 2, 1989). "Lear Joins With Columbia To Produce TV, Not Manage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021.

- "WB's 'Umptee-3' has Norman Lear's signature". Variety. September 15, 1997. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Snierson, Dan (March 14, 2003). "All in the Family's creator joins South Park". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "How Trey Parker and Matt Stone made South Park a success". Fortune. October 27, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- Ewing, Heidi; Grady, Rachel (July 5, 2016). "Not Dead Yet". The New York Times. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- Verdier, Hannah (May 11, 2017). "All of the Above With Norman Lear: the 94-year-old king of podcasts". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "All of the Above with Norman Lear on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Friedlander, Whitney (July 29, 2019). "Rita Moreno documentary coming from Lin-Manuel Miranda and Norman Lear". CNN Digital.

- "'Who's the Boss' Sequel in the Works at Sony". The Hollywood Reporter. August 4, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- EVEN THIS I GET TO EXPERIENCE | Kirkus Reviews.

- "ACT III". Norman Lear. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- Pond, Steve (September 15, 2019). "Norman Lear Breaks an Emmy Record, Becomes the Oldest Winner Ever".

- "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- "Past Recipients". Wif.org. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- "February 2017, NHMC National Hispanic Media Coalition". NHMC National Hispanic Media Coalition. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- "The Woody Guthrie Center Presents Woody Guthrie Prize Honoring Norman Lear – GRAMMY Museum". Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- "Norman Lear to receive Woody Guthrie Prize and Peabody Award". Oklahoman.com. April 12, 2017.

- Baumgaertner, Emily (August 3, 2017). "Kennedy Center Announces First Honorees of Trump Administration (Published 2017)". The New York Times.

- Low, Elaine (October 25, 2019). "Britannia Awards Highlight the Breadth of U.K. Talent". Variety. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "de beste bron van informatie over theoscarsite. Deze website is te koop!". theoscarsite.com. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Brownstein, Ronald (1990). The Power and the Glitter: The Hollywood–Washington Connection. Pantheon Books. pp. 203–211. ISBN 9780394569383.

- Brownstein, Ronald (June 28, 1987). "The Man Who Would Be Kingmaker". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Lacher, Irene (December 28, 1990). "Ultimate Outsider : Leftist and Fractious, the Nation Is Still Going Strong After 125 Years". Los Angeles Times.

- Day, Patrick Kevin (October 7, 2011). "Norman Lear Celebrates 30 Years of People For the American Way". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- Johnson, Ted (November 27, 2011). "Lear sees politics the American way". Variety.

- Interview: Anti-Christian-Right Crusader Norman Lear on Becoming a 'Born-Again American' US News, Dan Gilgoff, February 10, 2009, Accessed February 26, 2013

- A Profile of Norman Lear: Another Pilgrim's Progress Archived October 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Norman Lear.com, Martin E Marty, Accessed February 26, 2013

- "Norman Lear on race in America, Judaism, World War II and his bright future". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. December 17, 2014.

- Lear, Norman (July 12, 1992). "A False Picture Presented of Hollywood's Role in Politics". The Buffalo News. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Board of Trustees". Paleycenter.org. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Today Show interview with Katie Couric, February 8, 2002

- "press | Norman Lear | television, film, political and social activist, philanthropist".

- "Road Trip Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- "Yahoo! Helps Declare Yourself Drive More Than 1 Million Young Americans to Download Voter Registration Forms for 2004 Election". Yahoo! recent news. Yahoo! Inc. October 27, 2004. Archived from the original (Press release) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- "98 Prominent Hollywood Jews Back Iran Nuclear Deal in Open Letter (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Behrens, Leigh (February 28, 1988). "Frances Lear: 'Women Are Bursting Forth With Their Creativity'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Nemy, Enid (October 1, 1996). "Frances Lear, a Mercurial Figure of the Media and a Magazine Founder, Dead at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Katey Sagal on Wise Guys, Lost and More!. December 9, 2005. TV Guide.com. Retrieved on December 30, 2015.

- Grisar, PJ (July 27, 2022). "For Norman Lear on his 100th birthday". The Forward. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- "Happy Birthday To Me" - Paul Hipp, YouTube, July 22, 2015

- CBS News Sunday Morning interview with Norman Lear on January 10, 2021. "What makes Norman Lear, at 98, still tick?".

External links

- Official website

- Norman Lear at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 2007 biography of Norman Lear at the Museum of Broadcast Communications website (archived)

- Norman Lear Interview Silver Screen Studios - Dispatches from Quarantine (June 29, 2020)