Philip Glass

Philip Morris Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century.[1][2][3] Glass's work has been associated with minimalism, being built up from repetitive phrases and shifting layers.[4] Glass describes himself as a composer of "music with repetitive structures",[5] which he has helped evolve stylistically.[6][7]

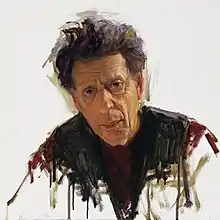

Philip Glass | |

|---|---|

Glass in Florence, 1993 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Philip Morris Glass |

| Born | January 31, 1937 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) | Composer |

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Website | philipglass |

| notable work: Full list | |

Glass founded the Philip Glass Ensemble, with which he still performs on keyboards. He has written fifteen operas, numerous chamber operas and musical theatre works, fourteen symphonies, twelve concertos, nine string quartets and various other chamber music, and several film scores. Three of his film scores have been nominated for an Academy Award.

Life and work

1937–1964: Beginnings, early education and influences

Philip Morris[8] Glass was born in Baltimore, Maryland,[9][10] on January 31, 1937,[11] the son of Ida (née Gouline) and Benjamin Charles Glass.[12] His family were Lithuanian-Jewish emigrants.[13][14] His father owned a record store and his mother was a librarian.[15] In his memoir, Glass recalls that at the end of World War II his mother aided Jewish Holocaust survivors, inviting recent arrivals to America to stay at their home until they could find a job and a place to live.[16]: 14 She developed a plan to help them learn English and develop skills so they could find work.[16]: 15 His sister, Sheppie, would later do similar work as an active member of the International Rescue Committee.[16]: 15

Glass developed his appreciation of music from his father, discovering later his father's side of the family had many musicians. His cousin Cevia was a classical pianist, while others had been in vaudeville. He learned his family was also related to Al Jolson.[16]: 16 Glass's father often received promotional copies of new recordings at his music store. Glass spent many hours listening to them, developing his knowledge and taste in music. This openness to modern sounds affected Glass at an early age:

My father was self-taught, but he ended up having a very refined and rich knowledge of classical, chamber, and contemporary music. Typically he would come home and have dinner, and then sit in his armchair and listen to music until almost midnight. I caught on to this very early, and I would go and listen with him.[16]: 17

The elder Glass promoted both new recordings and a wide selection of composers to his customers, sometimes convincing them to try something new by allowing them to return records they didn't like.[16]: 17 His store soon developed a reputation as Baltimore's leading source of modern music.[17] Glass built a sizable record collection from the unsold records in his father's store, including modern classical music such as Hindemith, Bartók, Schoenberg,[18] Shostakovich and Western classical music including Beethoven's string quartets and Schubert's B♭ Piano Trio. Glass cites Schubert's work as a "big influence" growing up.[19] In a 2011 interview, Glass stated that Franz Schubert—with whom he shares a birthday—is his favorite composer.[20]

He studied the flute as a child at the Peabody Preparatory of the Peabody Institute of Music. At the age of 15, he entered an accelerated college program at the University of Chicago where he studied mathematics and philosophy.[21] In Chicago, he discovered the serialism of Anton Webern and composed a twelve-tone string trio.[22] In 1954, Glass traveled to Paris, where he encountered the films of Jean Cocteau, which made a lasting impression on him. He visited artists' studios and saw their work; Glass recalls, "the bohemian life you see in [Cocteau's] Orphée was the life I ... was attracted to, and those were the people I hung out with."[23]

Glass studied at the Juilliard School of Music where the keyboard was his main instrument. His composition teachers included Vincent Persichetti and William Bergsma. Fellow students included Steve Reich and Peter Schickele. In 1959, he was a winner in the BMI Foundation's BMI Student Composer Awards, an international prize for young composers. In the summer of 1960, he studied with Darius Milhaud at the summer school of the Aspen Music Festival and composed a violin concerto for a fellow student, Dorothy Pixley-Rothschild.[24] After leaving Juilliard in 1962, Glass moved to Pittsburgh and worked as a school-based composer-in-residence in the public school system, composing various choral, chamber, and orchestral music.[25]

1964–1966: Paris

In 1964, Glass received a Fulbright Scholarship; his studies in Paris with the eminent composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, from autumn of 1964 to summer of 1966, influenced his work throughout his life, as the composer admitted in 1979: "The composers I studied with Boulanger are the people I still think about most—Bach and Mozart."[26]

Glass later stated in his autobiography Music by Philip Glass (1987) that the new music performed at Pierre Boulez's Domaine Musical concerts in Paris lacked any excitement for him (with the notable exceptions of music by John Cage and Morton Feldman), but he was deeply impressed by new films and theatre performances. His move away from modernist composers such as Boulez and Stockhausen was nuanced, rather than outright rejection: "That generation wanted disciples and as we didn't join up it was taken to mean that we hated the music, which wasn't true. We'd studied them at Juilliard and knew their music. How on earth can you reject Berio? Those early works of Stockhausen are still beautiful. But there was just no point in attempting to do their music better than they did and so we started somewhere else."[27]

During this time, he encountered revolutionary films of the French New Wave, such as those of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, which upended the rules set by an older generation of artists,[28] and Glass made friends with American visual artists (the sculptor Richard Serra and his wife Nancy Graves),[29] actors and directors (JoAnne Akalaitis, Ruth Maleczech, David Warrilow, and Lee Breuer, with whom Glass later founded the experimental theatre group Mabou Mines). Together with Akalaitis (they married in 1965), Glass in turn attended performances by theatre groups including Jean-Louis Barrault's Odéon theatre, The Living Theatre and the Berliner Ensemble in 1964 to 1965.[30] These significant encounters resulted in a collaboration with Breuer for which Glass contributed music for a 1965 staging of Samuel Beckett's Comédie (Play, 1963). The resulting piece (written for two soprano saxophones) was directly influenced by the play's open-ended, repetitive and almost musical structure and was the first one of a series of four early pieces in a minimalist, yet still dissonant, idiom.[22] After Play, Glass also acted in 1966 as music director of a Breuer production of Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children, featuring the theatre score by Paul Dessau.

In parallel with his early excursions in experimental theatre, Glass worked in winter 1965 and spring 1966 as a music director and composer[31] on a film score (Chappaqua, Conrad Rooks, 1966) with Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha, which added another important influence on Glass's musical thinking. His distinctive style arose from his work with Shankar and Rakha and their perception of rhythm in Indian music as being entirely additive. He renounced all his compositions in a moderately modern style resembling Milhaud's, Aaron Copland's, and Samuel Barber's, and began writing pieces based on repetitive structures of Indian music and a sense of time influenced by Samuel Beckett: a piece for two actresses and chamber ensemble, a work for chamber ensemble and his first numbered string quartet (No. 1, 1966).[32]

Glass then left Paris for northern India in 1966, where he came in contact with Tibetan refugees and began to gravitate towards Buddhism. He met Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, in 1972, and has been a strong supporter of the Tibetan independence ever since.

1967–1974: Minimalism: From Strung Out to Music in 12 Parts

Glass' musical style is instantly recognizable, with its trademark churning ostinatos, undulating arpeggios and repeating rhythms that morph over various lengths of time atop broad fields of tonal harmony. That style has taken permanent root in our pop-middlebrow sensibility. Glass' music is now indelibly a part of our cultural lingua franca, just a click away on YouTube.

John von Rhein, Chicago Tribune writer[21]

Shortly after arriving in New York City in March 1967, Glass attended a performance of works by Steve Reich (including the ground-breaking minimalist piece Piano Phase), which left a deep impression on him; he simplified his style and turned to a radical "consonant vocabulary".[22] Finding little sympathy from traditional performers and performance spaces, Glass eventually formed an ensemble with fellow ex-student Jon Gibson, and others, and began performing mainly in art galleries and studio lofts of SoHo. The visual artist Richard Serra provided Glass with Gallery contacts, while both collaborated on various sculptures, films and installations; from 1971 to 1974, he was Serra's regular studio assistant.[29][33]

Between summer of 1967 and the end of 1968, Glass composed nine works, including Strung Out (for amplified solo violin, composed in summer of 1967), Gradus (for solo saxophone, 1968), Music in the Shape of a Square (for two flutes, composed in May 1968, an homage to Erik Satie), How Now (for solo piano, 1968) and 1+1 (for amplified tabletop, November 1968) which were "clearly designed to experiment more fully with his new-found minimalist approach".[34] The first concert of Glass's new music was at Jonas Mekas's Film-Makers Cinemathèque (Anthology Film Archives) in September 1968. This concert included the first work of this series with Strung Out (performed by the violinist Pixley-Rothschild) and Music in the Shape of a Square (performed by Glass and Gibson). The musical scores were tacked on the wall, and the performers had to move while playing. Glass's new works met with a very enthusiastic response by the audience which consisted mainly of visual and performance artists who were highly sympathetic to Glass's reductive approach.

Apart from his music career, Glass had a moving company with his cousin, the sculptor Jene Highstein, and also worked as a plumber and cab driver (during 1973 to 1978). He recounts installing a dishwasher and looking up from his work to see an astonished Robert Hughes, Time magazine's art critic, staring at him.[35] During this time, he made friends with other New York-based artists such as Sol LeWitt, Nancy Graves, Michael Snow, Bruce Nauman, Laurie Anderson, and Chuck Close (who created a now-famous portrait of Glass).[36] (Glass returned the compliment in 2005 with A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close for piano.)

With 1+1 and Two Pages (composed in February 1969), Glass turned to a more "rigorous approach" to his "most basic minimalist technique, additive process",[37] pieces which were followed in the same year by Music in Contrary Motion and Music in Fifths (a kind of homage to his composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, who pointed out "hidden fifths" in his works but regarded them as cardinal sins). Eventually Glass's music grew less austere, becoming more complex and dramatic, with pieces such as Music in Similar Motion (1969), and Music with Changing Parts (1970). These pieces were performed by the Philip Glass Ensemble in the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1969 and in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1970, often encountering hostile reaction from critics,[22] but Glass's music was also met with enthusiasm from younger artists such as Brian Eno and David Bowie (at the Royal College of Art ca. 1970).[38] Eno described this encounter with Glass's music as one of the "most extraordinary musical experiences of [his] life", as a "viscous bath of pure, thick energy", concluding "this was actually the most detailed music I'd ever heard. It was all intricacy, exotic harmonics".[39] In 1970, Glass returned to the theatre, composing music for the theatre group Mabou Mines, resulting in his first minimalist pieces employing voices: Red Horse Animation and Music for Voices (both 1970, and premiered at the Paula Cooper Gallery).[40]

After differences of opinion with Steve Reich in 1971,[22] Glass formed the Philip Glass Ensemble (while Reich formed Steve Reich and Musicians), an amplified ensemble including keyboards, wind instruments (saxophones, flutes), and soprano voices.

Glass's music for his ensemble culminated in the four-hour-long Music in Twelve Parts (1971–1974), which began as a single piece with twelve instrumental parts but developed into a cycle that summed up Glass's musical achievement since 1967, and even transcended it—the last part features a twelve-tone theme, sung by the soprano voice of the ensemble. "I had broken the rules of modernism and so I thought it was time to break some of my own rules", according to Glass.[41] Though he finds the term minimalist inaccurate to describe his later work, Glass does accept this term for pieces up to and including Music in 12 Parts, excepting this last part which "was the end of minimalism" for Glass. As he pointed out: "I had worked for eight or nine years inventing a system, and now I'd written through it and come out the other end."[41] He now prefers to describe himself as a composer of "music with repetitive structures".[21]

1975–1979: Another Look at Harmony: The Portrait Trilogy

| External images | |

|---|---|

Glass continued his work with a series of instrumental works, called Another Look at Harmony (1975–1977). For Glass, this series demonstrated a new start, hence the title: "What I was looking for was a way of combining harmonic progression with the rhythmic structure I had been developing, to produce a new overall structure. ... I'd taken everything out with my early works and it was now time to decide just what I wanted to put in—a process that would occupy me for several years to come."[41]

Parts 1 and 2 of Another Look at Harmony were included in a collaboration with Robert Wilson, a piece of musical theater later designated by Glass as the first opera of his portrait opera trilogy: Einstein on the Beach. Composed in spring to fall of 1975 in close collaboration with Wilson, Glass's first opera was first premiered in summer 1976 at the Festival d'Avignon, and in November of the same year to a mixed and partly enthusiastic reaction from the audience at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Scored for the Philip Glass Ensemble, solo violin, chorus, and featuring actors (reciting texts by Christopher Knowles, Lucinda Childs and Samuel M. Johnson), Glass's and Wilson's essentially plotless opera was conceived as a "metaphorical look at Albert Einstein: scientist, humanist, amateur musician—and the man whose theories ... led to the splitting of the atom", evoking nuclear holocaust in the climactic scene, as critic Tim Page pointed out.[42] As with Another Look at Harmony, "Einstein added a new functional harmony that set it apart from the early conceptual works".[42] Composer Tom Johnson came to the same conclusion, comparing the solo violin music to Johann Sebastian Bach, and the "organ figures ... to those Alberti basses Mozart loved so much".[43] The piece was praised by The Washington Post as "one of the seminal artworks of the century".

Einstein on the Beach was followed by further music for projects by the theatre group Mabou Mines such as Dressed like an Egg (1975), and again music for plays and adaptations from prose by Samuel Beckett, such as The Lost Ones (1975), Cascando (1975), Mercier and Camier (1979). Glass also turned to other media; two multi-movement instrumental works for the Philip Glass Ensemble originated as music for film and TV: North Star (1977 score for the documentary North Star: Mark di Suvero by François de Menil and Barbara Rose) and four short cues for the children's TV series Sesame Street named Geometry of Circles (1979).

Another series, Fourth Series (1977–79), included music for chorus and organ ("Part One", 1977), organ and piano ("Part Two" and "Part Four", 1979), and music for a radio adaption of Constance DeJong's novel Modern Love ("Part Three", 1978). "Part Two" and "Part Four" were used (and hence renamed) in two dance productions by choreographer Lucinda Childs (who had already contributed to and performed in Einstein on the Beach). "Part Two" was included in Dance (a collaboration with visual artist Sol LeWitt, 1979), and "Part Four" was renamed as Mad Rush, and performed by Glass on several occasions such as the first public appearance of the 14th Dalai Lama in New York City in fall 1981. The piece demonstrates Glass's turn to more traditional models: the composer added a conclusion to an open-structured piece which "can be interpreted as a sign that he [had] abandoned the radical non-narrative, undramatic approaches of his early period", as the pianist Steffen Schleiermacher points out.[44]

In spring 1978, Glass received a commission from the Netherlands Opera (as well as a Rockefeller Foundation grant) which "marked the end of his need to earn money from non-musical employment".[45] With the commission Glass continued his work in music theater, composing his opera Satyagraha (composed in 1978–1979, premiered in 1980 at Rotterdam), based on the early life of Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa, Leo Tolstoy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Martin Luther King Jr. For Satyagraha, Glass worked in close collaboration with two "SoHo friends": the writer Constance deJong, who provided the libretto, and the set designer Robert Israel. This piece was in other ways a turning point for Glass, as it was his first work since 1963 scored for symphony orchestra, even if the most prominent parts were still reserved for solo voices and chorus. Shortly after completing the score in August 1979, Glass met the conductor Dennis Russell Davies, whom he helped prepare for performances in Germany (using a piano-four-hands version of the score); together they started to plan another opera, to be premiered at the Stuttgart State Opera.[28]

1980–1986: Completing the Portrait Trilogy: Akhnaten and beyond

.jpg.webp)

While planning a third part of his "Portrait Trilogy", Glass turned to smaller music theatre projects such as the non-narrative Madrigal Opera (for six voices and violin and viola, 1980), and The Photographer, a biographic study on the photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1982). Glass also continued to write for the orchestra with the score of Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1981–1982). Some pieces which were not used in the film (such as Façades) eventually appeared on the album Glassworks (1982, CBS Records), which brought Glass's music to a wider public.

The "Portrait Trilogy" was completed with Akhnaten (1982–1983, premiered in 1984), a vocal and orchestral composition sung in Akkadian, Biblical Hebrew, and Ancient Egyptian. In addition, this opera featured an actor reciting ancient Egyptian texts in the language of the audience. Akhnaten was commissioned by the Stuttgart Opera in a production designed by Achim Freyer. It premiered simultaneously at the Houston Opera in a production directed by David Freeman and designed by Peter Sellars. At the time of the commission, the Stuttgart Opera House was undergoing renovation, necessitating the use of a nearby playhouse with a smaller orchestra pit. Upon learning this, Glass and conductor Dennis Russell Davies visited the playhouse, placing music stands around the pit to determine how many players the pit could accommodate. The two found they could not fit a full orchestra in the pit. Glass decided to eliminate the violins, which had the effect of "giving the orchestra a low, dark sound that came to characterize the piece and suited the subject very well".[28] As Glass remarked in 1992, Akhnaten is significant in his work since it represents a "first extension out of a triadic harmonic language", an experiment with the polytonality of his teachers Persichetti and Milhaud, a musical technique which Glass compares to "an optical illusion, such as in the paintings of Josef Albers".[46]

Glass again collaborated with Robert Wilson on another opera, the CIVIL warS (1983, premiered in 1984), which also functioned as the final part (the Rome section) of Wilson's epic work by the same name, originally planned for an "international arts festival that would accompany the Olympic Games in Los Angeles".[47] (Glass also composed a prestigious work for chorus and orchestra for the opening of the Games, The Olympian: Lighting of the Torch and Closing ). The premiere of The CIVIL warS in Los Angeles never materialized and the opera was in the end premiered at the Opera of Rome. Glass's and Wilson's opera includes musical settings of Latin texts by the 1st-century-Roman playwright Seneca and allusions to the music of Giuseppe Verdi and from the American Civil War, featuring the 19th century figures Giuseppe Garibaldi and Robert E. Lee as characters.

In the mid-1980s, Glass produced "works in different media at an extraordinarily rapid pace".[48] Projects from that period include music for dance (Glass Pieces choreographed for New York City Ballet by Jerome Robbins in 1983 to a score drawn from existing Glass compositions created for other media including an excerpt from Akhnaten; and In the Upper Room, Twyla Tharp, 1986), music for theatre productions Endgame (1984) and Company (1983). Beckett vehemently disapproved of the production of Endgame at the American Repertory Theater (Cambridge, Massachusetts), which featured JoAnne Akalaitis's direction and Glass's Prelude for timpani and double bass, but in the end, he authorized the music for Company, four short, intimate pieces for string quartet that were played in the intervals of the dramatization. This composition was initially regarded by the composer as a piece of Gebrauchsmusik ('music for use')—"like salt and pepper ... just something for the table", as he noted.[49] Eventually Company was published as Glass's String Quartet No. 2 and in a version for string orchestra, being performed by ensembles ranging from student orchestras to renowned formations such as the Kronos Quartet and the Kremerata Baltica.

This interest in writing for the string quartet and the string orchestra led to a chamber and orchestral film score for Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (Paul Schrader, 1984–85), which Glass recently described as his "musical turning point" that developed his "technique of film scoring in a very special way".[50]

Glass also dedicated himself to vocal works with two sets of songs, Three Songs for chorus (1984, settings of poems by Leonard Cohen, Octavio Paz and Raymond Lévesque), and a song cycle initiated by CBS Masterworks Records: Songs from Liquid Days (1985), with texts by songwriters such as David Byrne, Paul Simon, in which the Kronos Quartet is featured (as it is in Mishima) in a prominent role. Glass also continued his series of operas with adaptations from literary texts such as The Juniper Tree (an opera collaboration with composer Robert Moran, 1984), Edgar Allan Poe's The Fall of the House of Usher (1987), and also worked with novelist Doris Lessing on the opera The Making of the Representative for Planet 8 (1985–86, and performed by the Houston Grand Opera and English National Opera in 1988).

1987–1991: Operas and the turn to symphonic music

Compositions such as Company, Facades and String Quartet No. 3 (the last two extracted from the scores to Koyaanisqatsi and Mishima) gave way to a series of works more accessible to ensembles such as the string quartet and symphony orchestra, in this returning to the structural roots of his student days. In taking this direction his chamber and orchestral works were also written in a more and more traditional and lyrical style. In these works, Glass often employs old musical forms such as the chaconne and the passacaglia—for instance in Satyagraha,[22] the Violin Concerto No. 1 (1987), Symphony No. 3 (1995), Echorus (1995) and also recent works such as Symphony No. 8 (2005),[51] and Songs and Poems for Solo Cello (2006).

A series of orchestral works originally composed for the concert hall commenced with the three-movement Violin Concerto No. 1 (1987). This work was commissioned by the American Composers Orchestra and written for and in close collaboration with the violinist Paul Zukofsky and the conductor Dennis Russel Davies, who since then has encouraged the composer to write numerous orchestral pieces. The Concerto is dedicated to the memory of Glass's father: "His favorite form was the violin concerto, and so I grew up listening to the Mendelssohn, the Paganini, the Brahms concertos. ... So when I decided to write a violin concerto, I wanted to write one that my father would have liked."[52] Among its multiple recordings, in 1992, the Concerto was performed and recorded by Gidon Kremer and the Vienna Philharmonic. This turn to orchestral music was continued with a symphonic trilogy of "portraits of nature", commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra, the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra: The Light (1987), The Canyon (1988), and Itaipu (1989).

While composing for symphonic ensembles, Glass also composed music for piano, with the cycle of five movements titled Metamorphosis (adapted from music for a theatrical adaptation of Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis), and for the Errol Morris film The Thin Blue Line, 1988. In the same year Glass met the poet Allen Ginsberg by chance in a book store in the East Village of New York City, and they immediately "decided on the spot to do something together, reached for one of Allen's books and chose Wichita Vortex Sutra",[53] a piece for reciter and piano which in turn developed into a music theatre piece for singers and ensemble, Hydrogen Jukebox (1990).

Glass also returned to chamber music; he composed two String Quartets (No. 4 Buczak in 1989 and No. 5 in 1991), and chamber works which originated as incidental music for plays, such as Music from "The Screens" (1989/1990). This work originated in one of many theater music collaborations with the director JoAnne Akalaitis, who originally asked the Gambian musician Foday Musa Suso "to do the score [for Jean Genet's The Screens] in collaboration with a western composer".[54] Glass had already collaborated with Suso in the film score to Powaqqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1988). Music from "The Screens" is on occasion a touring piece for Glass and Suso (one set of tours also included percussionist Yousif Sheronick ), and individual pieces found their way into the repertoire of Glass and the cellist Wendy Sutter. Another collaboration was a collaborative recording project with Ravi Shankar, initiated by Peter Baumann (a member of the band Tangerine Dream), which resulted in the album Passages (1990).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Glass's projects also included two highly prestigious opera commissions based on the life of explorers: The Voyage (1992), with a libretto by David Henry Hwang, was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera for the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus; and White Raven (1991), about Vasco da Gama, a collaboration with Robert Wilson and composed for the closure of the 1998 World Fair in Lisbon. Especially in The Voyage, the composer "explore[d] new territory", with its "newly arching lyricism", "Sibelian starkness and sweep", and "dark, brooding tone ... a reflection of its increasingly chromatic (and dissonant) palette", as one commentator put it.[22]

Glass remixed the S'Express song "Hey Music Lover", for the b-side of its 1989 release as a single.[55]

1991–1996: Cocteau trilogy and symphonies

After these operas, Glass began working on a symphonic cycle, commissioned by the conductor Dennis Russell Davies, who told Glass at the time: "I'm not going to let you ... be one of those opera composers who never write a symphony".[56] Glass responded with a pair of three-movement symphonies ("Low" [1992], and Symphony No. 2 [1994]); his first in an ongoing series of symphonies is a combination of the composer's own musical material with themes featured in prominent tracks of the David Bowie/Brian Eno album Low (1977),[57] whereas Symphony No. 2 is described by Glass as a study in polytonality. He referred to the music of Honegger, Milhaud, and Villa-Lobos as possible models for his symphony.[58] With the Concerto Grosso (1992), Symphony No. 3 (1995), a Concerto for Saxophone Quartet and Orchestra (1995), written for the Rascher Quartet (all commissioned by conductor Dennis Russel Davies), and Echorus (1994/95), a more transparent, refined, and intimate chamber-orchestral style paralleled the excursions of his large-scale symphonic pieces. In the four movements of his Third Symphony, Glass treats a 19-piece string orchestra as an extended chamber ensemble. In the third movement, Glass re-uses the chaconne as a formal device; one commentator characterized Glass's symphony as one of the composer's "most tautly unified works".[59][60] The third Symphony was closely followed by a fourth, subtitled Heroes (1996), commissioned the American Composers Orchestra. Its six movements are symphonic reworkings of themes by Glass, David Bowie, and Brian Eno (from their album "Heroes", 1977); as in other works by the composer, it is also a hybrid work and exists in two versions: one for the concert hall, and another, shorter one for dance, choreographed by Twyla Tharp.

Another commission by Dennis Russell Davies was a second series for piano, the Etudes for Piano (dedicated to Davies as well as the production designer Achim Freyer); the complete first set of ten Etudes has been recorded and performed by Glass himself. Bruce Brubaker and Dennis Russell Davies have each recorded the original set of six. Most of the Etudes are composed in the post-minimalist and increasingly lyrical style of the times: "Within the framework of a concise form, Glass explores possible sonorities ranging from typically Baroque passagework to Romantically tinged moods".[61] Some of the pieces also appeared in different versions such as in the theatre music to Robert Wilson's Persephone (1994, commissioned by the Relache Ensemble) or Echorus (a version of Etude No. 2 for two violins and string orchestra, written for Edna Mitchell and Yehudi Menuhin 1995).

Glass's prolific output in the 1990s continued to include operas with an opera triptych (1991–1996), which the composer described as an "homage" to writer and film director Jean Cocteau, based on his prose and cinematic work: Orphée (1950), La Belle et la Bête (1946), and the novel Les Enfants terribles (1929, later made into a film by Cocteau and Jean-Pierre Melville, 1950). In the same way the triptych is also a musical homage to the work of the group of French composers associated with Cocteau, Les Six (and especially to Glass's teacher Darius Milhaud), as well as to various 18th-century composers such as Gluck and Bach whose music featured as an essential part of the films by Cocteau.

The inspiration of the first part of the trilogy, Orphée (composed in 1991, and premiered in 1993 at the American Repertory Theatre) can be conceptually and musically traced to Gluck's opera Orfeo ed Euridice (Orphée et Euridyce, 1762/1774),[22] which had a prominent part in Cocteau's 1949 film Orphee.[62] One theme of the opera, the death of Eurydice, has some similarity to the composer's personal life: the opera was composed after the unexpected death in 1991 of Glass's wife, artist Candy Jernigan: "... One can only suspect that Orpheus' grief must have resembled the composer's own", K. Robert Schwartz suggests.[22] The opera's "transparency of texture, a subtlety of instrumental color, ... a newly expressive and unfettered vocal writing"[22] was praised, and The Guardian's critic remarked "Glass has a real affinity for the French text and sets the words eloquently, underpinning them with delicately patterned instrumental textures".[63]

For the second opera, La Belle et la Bête (1994, scored for either the Philip Glass Ensemble or a more conventional chamber orchestra), Glass replaced the soundtrack (including Georges Auric's film music) of Cocteau's film, wrote "a new fully operatic score and synchronize[d] it with the film".[23] The final part of the triptych returned again to a more traditional setting with the "Dance Opera" Les Enfants terribles (1996), scored for voices, three pianos and dancers, with choreography by Susan Marshall. The characters are depicted by both singers and dancers. The scoring of the opera evokes Bach's Concerto for Four Harpsichords, but in another way also "the snow, which falls relentlessly throughout the opera ... bearing witness to the unfolding events. Here time stands still. There is only music, and the movement of children through space" (Glass).[64][65]

1997–2004: Symphonies, opera, and concertos

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Glass's lyrical and romantic styles peaked with a variety of projects: operas, theatre and film scores (Martin Scorsese's Kundun, 1997, Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi, 2002, and Stephen Daldry's The Hours, 2002), a series of five concerts, and three symphonies centered on orchestra-singer and orchestra-chorus interplay. Two symphonies, Symphony No. 5 "Choral" (1999) and Symphony No. 7 "Toltec" (2004), and the song cycle Songs of Milarepa (1997) have a meditative theme. The operatic Symphony No. 6 Plutonian Ode (2002) for soprano and orchestra was commissioned by the Brucknerhaus, Linz, and Carnegie Hall in celebration of Glass's sixty-fifth birthday, and developed from Glass's collaboration with Allen Ginsberg (poet, piano—Ginsberg, Glass), based on his poem of the same name.

Besides writing for the concert hall, Glass continued his ongoing operatic series with adaptions from literary texts: The Marriages of Zones 3, 4 and 5 ([1997] story-libretto by Doris Lessing), In the Penal Colony (2000, after the story by Franz Kafka), and the chamber opera The Sound of a Voice (2003, with David Henry Hwang), which features the Pipa, performed by Wu Man at its premiere. Glass also collaborated again with the co-author of Einstein on the Beach, Robert Wilson, on Monsters of Grace (1998), and created a biographic opera on the life of astronomer Galileo Galilei (2001).

In the early 2000s, Glass started a series of five concerti with the Tirol Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (2000, premiered by Dennis Russell Davies as conductor and soloist), and the Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists and Orchestra (2000, for the timpanist Jonathan Haas). The Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (2001) had its premiere performance in Beijing, featuring cellist Julian Lloyd Webber; it was composed in celebration of his fiftieth birthday.[66] These concertos were followed by the concise and rigorously neo-Baroque Concerto for Harpsichord and Orchestra (2002), demonstrating in its transparent, chamber orchestral textures Glass's classical technique, evocative in the "improvisatory chords" of its beginning a toccata of Froberger or Frescobaldi, and 18th century music.[67] Two years later, the concerti series continued with Piano Concerto No. 2: After Lewis and Clark (2004), composed for the pianist Paul Barnes. The concerto celebrates the pioneers' trek across North America, and the second movement features a duet for piano and Native American flute. With the chamber opera The Sound of a Voice, Glass's Piano Concerto No. 2 might be regarded as bridging his traditional compositions and his more popular excursions to World Music, also found in Orion (also composed in 2004).

2005–2007: Songs and Poems

Waiting for the Barbarians, an opera from J. M. Coetzee's novel (with the libretto by Christopher Hampton), had its premiere performance in September 2005. Glass defined the work as a "social/political opera", as a critique on the Bush administration's war in Iraq, a "dialogue about political crisis", and an illustration of the "power of art to turn our attention toward the human dimension of history".[68] While the opera's themes are Imperialism, apartheid, and torture, the composer chose an understated approach by using "very simple means, and the orchestration is very clear and very traditional; it's almost classical in sound", as the conductor Dennis Russell Davies notes.[69][70]

Two months after the premiere of this opera, in November 2005, Glass's Symphony No. 8, commissioned by the Bruckner Orchestra Linz, was premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York City. After three symphonies for voices and orchestra, this piece was a return to purely orchestral and abstract composition; like previous works written for the conductor Dennis Russell Davies (the 1992 Concerto Grosso and the 1995 Symphony No. 3), it features extended solo writing. Critic Allan Kozinn described the symphony's chromaticism as more extreme, more fluid, and its themes and textures as continually changing, morphing without repetition, and praised the symphony's "unpredictable orchestration", pointing out the "beautiful flute and harp variation in the melancholy second movement".[71] Alex Ross, remarked that "against all odds, this work succeeds in adding something certifiably new to the overstuffed annals of the classical symphony. ... The musical material is cut from familiar fabric, but it's striking that the composer forgoes the expected bustling conclusion and instead delves into a mood of deepening twilight and unending night."[72]

The Passion of Ramakrishna (2006), was composed for the Pacific Symphony orchestra, the Pacific Chorale and the conductor Carl St. Clair. The 45 minutes choral work is based on the writings of Indian spiritual leader Ramakrishna, which seem "to have genuinely inspired and revived the composer out of his old formulas to write something fresh", as one critic remarked, whereas another noted "The musical style breaks little new ground for Glass, except for the glorious Handelian ending ... the composer's style ideally fits the devotional text".[73][74]

A cello suite, composed for the cellist Wendy Sutter, Songs and Poems for Solo Cello (2005–2007), was equally lauded by critics. It was described by Lisa Hirsch as "a major work, ... a major addition to the cello repertory" and "deeply Romantic in spirit, and at the same time deeply Baroque".[75] Another critic, Anne Midgette of The Washington Post, noted the suite "maintains an unusual degree of directness and warmth"; she also noted a kinship to a major work by Johann Sebastian Bach: "Digging into the lower registers of the instrument, it takes flight in handfuls of notes, now gentle, now impassioned, variously evoking the minor-mode keening of klezmer music and the interior meditations of Bach's cello suites".[76] Glass himself pointed out "in many ways it owes more to Schubert than to Bach".[77]

In 2007, Glass also worked alongside Leonard Cohen on an adaptation of Cohen's poetry collection Book of Longing. The work, which premiered in June 2007 in Toronto, is a piece for seven instruments and a vocal quartet, and contains recorded spoken word performances by Cohen and imagery from his collection.

Appomattox, an opera surrounding the events at the end of the American Civil War, was commissioned by the San Francisco Opera and premiered on October 5, 2007. As in Waiting for the Barbarians, Glass collaborated with the writer Christopher Hampton, and as with the preceding opera and Symphony No. 8, the piece was conducted by Glass's long-time collaborator Dennis Russell Davies, who noted "in his recent operas the bass line has taken on an increasing prominence,... (an) increasing use of melodic elements in the deep register, in the contrabass, the contrabassoon—he's increasingly using these sounds and these textures can be derived from using these instruments in different combinations. ... He's definitely developed more skill as an orchestrator, in his ability to conceive melodies and harmonic structures for specific instrumental groups. ... what he gives them to play is very organic and idiomatic."[70]

Apart from this large-scale opera, Glass added a work to his catalogue of theater music in 2007, and continuing—after a gap of twenty years—to write music for the dramatic work of Samuel Beckett. He provided a "hypnotic" original score for a compilation of Beckett's short plays Act Without Words I, Act Without Words II, Rough for Theatre I and Eh Joe, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis and premiered in December 2007. Glass's work for this production was described by The New York Times as "icy, repetitive music that comes closest to piercing the heart".[78]

2008–present: Chamber music, concertos, and symphonies

2008 to 2010 Glass continued to work on a series of chamber music pieces which started with Songs and Poems: the Four Movements for Two Pianos (2008, premiered by Dennis Davies and Maki Namekawa in July 2008), a Sonata for Violin and Piano composed in "the Brahms tradition" (completed in 2008, premiered by violinist Maria Bachman and pianist Jon Klibonoff in February 2009); a String sextet (an adaption of the Symphony No. 3 of 1995 made by Glass's musical director Michael Riesman) followed in 2009. Pendulum (2010, a one-movement piece for violin and piano), a second Suite of cello pieces for Wendy Sutter (2011), and Partita for solo violin for violinist Tim Fain (2010, first performance of the complete work 2011), are recent entries in the series.[79]

Other works for the theater were a score for Euripides' The Bacchae (2009, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis), and Kepler (2009), yet another operatic biography of a scientist or explorer. The opera is based on the life of 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler, against the background of the Thirty Years' War, with a libretto compiled from Kepler's texts and poems by his contemporary Andreas Gryphius. It is Glass's first opera in German, and was premiered by the Bruckner Orchestra Linz and Dennis Russell Davies in September 2009. LA Times critic Mark Swed and others described the work as "oratorio-like"; Swed pointed out the work is Glass's "most chromatic, complex, psychological score" and "the orchestra dominates ... I was struck by the muted, glowing colors, the character of many orchestral solos and the poignant emphasis on bass instruments".[80]

In 2009 and 2010, Glass returned to the concerto genre. Violin Concerto No. 2 in four movements was commissioned by violinist Robert McDuffie, and subtitled "The American Four Seasons" (2009), as an homage to Vivaldi's set of concertos The Four Seasons. It premiered in December 2009 by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and was subsequently performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra in April 2010.[81] The Double Concerto for Violin and Cello and Orchestra (2010) was composed for soloists Maria Bachmann and Wendy Sutter and also as a ballet score for the Nederlands Dans Theater.[82][83] Other orchestral projects of 2010 are short orchestral scores for films; to a multimedia presentation based on the novel Icarus at the Edge of Time by theoretical physicist Brian Greene, which premiered on June 6, 2010, and the score for the Brazilian film Nosso Lar (released in Brazil on September 3, 2010). Glass also donated a short work, Brazil, to the video game Chime, which was released on February 3, 2010.

In January 2011, Glass performed at the MONA FOMA festival in Hobart, Tasmania. The festival promotes a broad range of art forms, including experimental sound, noise, dance, theatre, visual art, performance and new media.[84]

In August 2011, Glass presented a series of music, dance, and theater performances as part of the Days and Nights Festival.[85] Along with the Philip Glass Ensemble, scheduled performers include Molissa Fenley and Dancers, John Moran with Saori Tsukada, as well as a screening of Dracula with Glass's score.[86] Glass hopes to present this festival annually, with a focus on art, science, and conservation.[87]

Other works completed since 2010 include Symphony No. 9 (2010–2011), Symphony No. 10 (2012), Cello Concerto No. 2 (2012, based on the film score to Naqoyqatsi) as well as String Quartet No. 6 and No. 7. Glass's Ninth Symphony was co-commissioned by the Bruckner Orchestra Linz, the American Composers Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. The symphony's first performance took place on January 1, 2012, at the Brucknerhaus in Linz, Austria (Dennis Russell Davies conducting the Bruckner Orchestra Linz); the American premiere was on January 31, 2012, (Glass's 75th birthday), at Carnegie Hall (Dennis Russell Davies conducting the American Composers Orchestra), and the West Coast premiere with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under the baton of John Adams on April 5.[88] Glass's Tenth Symphony, written in five movements, was commissioned by the Orchestre français des jeunes for its 30th anniversary. The symphony's first performance took place on August 9, 2012, at the Grand Théâtre de Provence in Aix-en-Provence under Dennis Russell Davies.[89][90][91][92]

The opera The Perfect American was composed in 2011 to a commission from Teatro Real Madrid.[93] The libretto is based on a book of the same name by Peter Stephan Jungk and covers the final months of the life of Walt Disney.[94] The world premiere was at the Teatro Real, Madrid, on January 22, 2013, with British baritone Christopher Purves taking the role of Disney.[94] The UK premiere took place on June 1, 2013, in a production by the English National Opera at the London Coliseum.[95] The US premiere took place on March 12, 2017, in a production by Long Beach Opera.[96]

His opera The Lost, based on a play by Austrian playwright and novelist Peter Handke, Die Spuren der Verirrten (2007), premiered at the Musiktheater Linz in April 2013, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies and directed by David Pountney.

On June 28, 2013, Glass's piano piece Two Movements for Four Pianos was premiered at the Museum Kunstpalast, performed by Katia and Marielle Labèque, Maki Namekawa and Dennis Russell Davies.[97]

On January 17, 2014, Glass' collaboration with Angélique Kidjo Ifé: Three Yorùbá Songs for Orchestra premiered at the Philharmonie Luxembourg.[98]

In May 2015, Glass's Double Concerto for Two Pianos was premiered by Katia and Marielle Labèque, Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Glass published his memoir, Words Without Music, in 2015.[99]

His 11th symphony, commissioned by the Bruckner Orchestra Linz, the Istanbul International Music Festival, and the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, premiered on January 31, 2017, Glass's 80th birthday, at Carnegie Hall, Dennis Russell Davies conducting the Bruckner Orchestra.[100][101] On September 22, 2017, his Piano Concerto No. 3 was premiered by pianist Simone Dinnerstein with the strings of the chamber orchestra A Far Cry at Jordan Hall at the New England Conservatory of Music, Boston, Massachusetts.[102]

Glass's 12th symphony was premiered by the Los Angeles Philharmonic under John Adams at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles on January 10, 2019. Commissioned by the orchestra, the work is based on David Bowie's 1979 album Lodger, it completes Glass's trilogy of symphonies based on Bowie's Berlin Trilogy of albums.[103]

In collaboration with stage auteur, performer and co-director (with Kirsty Housley) Phelim McDermott, he composed the score for the new work Tao of Glass, which premiered at the 2019 Manchester International Festival[104] before touring to the 2020 Perth Festival.

Influences and collaborations

Glass describes himself as a "classicist", pointing out he is trained in harmony and counterpoint and studied such composers as Franz Schubert, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with Nadia Boulanger.[105] Aside from composing in the Western classical tradition, his music has ties to rock, ambient music, electronic music, and world music. Early admirers of his minimalism include musicians Brian Eno and David Bowie.[106] In the 1990s, Glass composed the aforementioned symphonies Low (1992) and Heroes (1996), thematically derived from the Bowie-Eno collaboration albums Low and "Heroes" composed in late 1970s Berlin.

Glass has collaborated with recording artists such as Paul Simon, Suzanne Vega,[107] Mick Jagger,[108] Leonard Cohen, David Byrne, Uakti, Natalie Merchant,[109] S'Express (Glass remixed their track Hey Music Lover in 1989)[110] and Aphex Twin (yielding an orchestration of Icct Hedral in 1995 on the Donkey Rhubarb EP). Glass's compositional influence extends to musicians such as Mike Oldfield (who included parts from Glass's North Star in Platinum), and bands such as Tangerine Dream and Talking Heads. Glass and his sound designer Kurt Munkacsi produced the American post-punk/new wave band Polyrock (1978 to the mid-1980s), as well as the recording of John Moran's The Manson Family (An Opera) in 1991, which featured punk legend Iggy Pop, and a second (unreleased) recording of Moran's work featuring poet Allen Ginsberg.

Glass counts many artists among his friends and collaborators, including visual artists (Richard Serra, Chuck Close, Fredericka Foster),[111][112] writers (Doris Lessing, David Henry Hwang, Allen Ginsberg), film and theatre directors (including Errol Morris, Robert Wilson, JoAnne Akalaitis, Godfrey Reggio, Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese, Christopher Hampton, Bernard Rose, and many others), choreographers (Lucinda Childs, Jerome Robbins, Twyla Tharp), and musicians and composers (Ravi Shankar, David Byrne, the conductor Dennis Russell Davies, Foday Musa Suso, Laurie Anderson, Linda Ronstadt, Paul Simon, Pierce Turner, Joan La Barbara, Arthur Russell, David Bowie, Brian Eno, Roberto Carnevale, Patti Smith, Aphex Twin, Lisa Bielawa, Andrew Shapiro, John Moran, Bryce Dessner and Nico Muhly). Among recent collaborators are Glass's fellow New Yorker Woody Allen and Stephen Colbert.[113]

Glass had begun using the Farfisa portable organ out of convenience,[114] and he has used it in concert.[115] It is featured on several recordings including North Star[116] and Dance Nos. 1–5.[117][118]

Recording work

In 1970, Glass and Klaus Kertess (owner of the Bykert Gallery) formed a record label named Chatham Square Productions (named after the location of the studio of a Philip Glass Ensemble member Dick Landry).[28] In 1993 Glass formed another record label, Point Music; in 1997, Point Music released Music for Airports, a live, instrumental version of Eno's composition of the same name, by Bang on a Can All-Stars. In 2002, Glass and his producer Kurt Munkacsi and artist Don Christensen founded the Orange Mountain Music company, dedicated to "establishing the recording legacy of Philip Glass" and, to date, have released sixty albums of Glass's music.

Music for film

Glass has composed many film scores, starting with the orchestral score for Koyaanisqatsi (1982), and continuing with two biopics, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985, resulting in the String Quartet No. 3) and Kundun (1997) about the Dalai Lama, for which he received his first Academy Award nomination. In 1968 he composed and conducted the score for director Harrison Engle's minimalist comedy short, Railroaded, played by the Philip Glass Ensemble. This was one of his earliest film efforts.

The year after scoring Hamburger Hill (1987), Glass began a long collaboration with the filmmaker Errol Morris with his music for Morris's celebrated documentaries, including The Thin Blue Line (1988) and A Brief History of Time (1991).[119] He continued composing for the Qatsi trilogy with the scores for Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002). In 1995, he composed the theme for Reggio's short independent film Evidence. He made a cameo appearance—briefly visible performing at the piano—in Peter Weir's The Truman Show (1998), which uses music from Powaqqatsi, Anima Mundi and Mishima, as well as three original tracks by Glass. In the 1990s, he also composed scores for Bent (1997) and the supernatural horror film Candyman (1992) and its sequel, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (1995), plus a film adaptation of Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent (1996).

In 1999, he finished a new soundtrack for the 1931 film Dracula. The Hours (2002) earned him a second Academy Award nomination. The circular, recurring nature of Glass' music has been praised for providing stability and contrast to frequent jumps across time and geography in the film's narrative. In this way, the soundtrack has a distinctive personality, so much so that director Stephen Daldry believes Glass's music serves as "another stream of consciousness, another character"[120] in the film. The Hours was followed by another Morris documentary, The Fog of War (2003). In the mid-2000s Glass provided the scores to films such as Secret Window (2004), Neverwas (2005), The Illusionist and Notes on a Scandal, garnering his third Academy Award nomination for the latter. Glass's most recent film scores include No Reservations (Glass makes a brief cameo in the film sitting at an outdoor café), Cassandra's Dream (2007), Les Regrets (2009), Mr Nice (2010), the Brazilian film Nosso Lar (2010) and Fantastic Four (2015, in collaboration with Marco Beltrami). In 2009, Glass composed original theme music for Transcendent Man, about the life and ideas of Ray Kurzweil by filmmaker Barry Ptolemy.

In the 2000s, Glass's work from the 1980s again became known to wider public through various media. In 2005, his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1987) was featured in the surreal French thriller, La Moustache, providing a tone intentionally incongruous to the banality of the movie's plot.[121] Metamorphosis: Metamorphosis One from Solo Piano (1989) was featured in the reimagined Battlestar Galactica in the episode "Valley of Darkness"[122] and also in the final episode ("return 0") of Person of Interest. In 2008, Rockstar Games released Grand Theft Auto IV featuring Glass's "Pruit Igoe" (from Koyaanisqatsi). "Pruit Igoe" and "Prophecies" (also from Koyaanisqatsi) were used both in a trailer for Watchmen and in the film itself. Watchmen also included two other Glass pieces in the score: "Something She Has To Do" from The Hours and "Protest" from Satyagraha, act 2, scene 3. In 2013, Glass contributed a piano piece "Duet" to the Park Chan-wook film Stoker which is performed diegetically in the film.[123][124] In 2017, Glass scored the National Geographic Films documentary Jane (a documentary on the life of renowned British primatologist Jane Goodall).

Glass's music was featured in two award-winning films by Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev, Elena (2011) and Leviathan (2014).

For television, Glass composed the theme for Night Stalker (2005) and the soundtrack for Tales from the Loop (2020). Glass's "Confrontation and Rescue" (from Satyagraha) was used in the ending of Season 3 Chapter 6 of Stranger Things (2019), whilst "Window of Appearances", "Akhnaten and Nefertiti" (from Akhnaten) and "Prophecies" (from Koyaanisqatsi) were used in the finale of Season 4 Volume 1 (2022).

Personal life

Glass lives in New York and in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. He has described himself as "a Jewish-Taoist-Hindu-Toltec-Buddhist"[18] and is a supporter of the Tibetan independence movement. In 1987, he co-founded the Tibet House US with Columbia University professor Robert Thurman and the actor Richard Gere at the request of the 14th Dalai Lama.[125] Glass is a vegetarian.[126]

Glass has been married four times; he has four children and one granddaughter.

- His first marriage was to theater director JoAnne Akalaitis (m. 1965, div. 1980), with whom he has two children: Juliet (b. 1968) and Zachary (b. 1971).

- His second marriage was to Luba Burtyk (m. 1980), a physician.[127][128]

- His third wife, the artist Candy Jernigan, died of liver cancer in 1991, aged 39.

- Glass's fourth marriage was to restaurant manager, Holly Critchlow (m. in 2001), whom he later divorced.[13] They had two sons, Cameron (b. 2002) and Marlowe (b. 2003).

He was romantically involved with cellist Wendy Sutter for approximately five years.[129][130] As of December 2018, his partner was Japanese-born dancer Saori Tsukada.[131][132]

Glass is the first cousin once removed of Ira Glass, host of the radio show This American Life.[133] Ira interviewed Glass onstage at Chicago's Field Museum; this interview was broadcast on NPR's Fresh Air. Ira interviewed Glass a second time at a fundraiser for St. Ann's Warehouse; this interview was given away to public-radio listeners as a pledge-drive thank-you gift in 2010. Ira and Glass recorded a version of the composition Glass wrote to accompany his friend Allen Ginsberg's poem "Wichita Vortex Sutra". In 2014, This American Life broadcast a live performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music that included the world premier of the opera Help, a short monodrama that Philip Glass wrote for the occasion.[134]

Critical reception

.jpg.webp)

Musical Opinion said, "Philip Glass must be one of the most influential living composers."[135] The National Endowment for the Arts, while noting that many of his operas have been produced by the world's leading opera houses said, "He is the first composer to win a wide, multigenerational audience in the opera house, the concert hall, the dance world, in film, and in popular music."[136] Classical Music Review called his opera Akhnaten "a musically sophisticated and imposing work."[137]

Justin Davidson of New York magazine has criticized Glass, saying, "Glass never had a good idea he didn't flog to death: He repeats the haunting scale 30 mind-numbing times, until it's long past time to go home."[138] Richard Schickel of Time criticized Glass's score for The Hours, saying, "This ultimately proves insufficient to lend meaning to their lives or profundity to a grim and uninvolving film, for which Philip Glass unwittingly provides the perfect score—tuneless, oppressive, droning, painfully self-important."[139]

Michael White of The Daily Telegraph described Glass' Violin Concerto No. 2 as being

as rewarding as chewing gum that's lost its flavour, and they're not dissimilar activities. This new concerto is unmitigated trash: the usual strung out sequences of arpeggiated banality, driven by the rise and fall of fast-moving but still leaden triplets, and vacuously formulaic. Philip Glass is no Vivaldi, a composer who even at his most wallpaper baroque still has something to say. Glass has nothing—though he presumably deludes himself into thinking he does: hence the preponderance of slow, reflective solo writing in the piece which assumes there's something to reflect on.[140]

Documentaries about Glass

- Music with Roots in the Aether: Opera for Television (1976). Tape 2: Philip Glass. Produced and directed by Robert Ashley

- Philip Glass, from Four American Composers (1983); directed by Peter Greenaway

- A Composer's Notes: Philip Glass and the Making of an Opera (1985); directed by Michael Blackwood

- Einstein on the Beach: The Changing Image of Opera (1986); directed by Mark Obenhaus

- Looking Glass (2005); directed by Éric Darmon

- Glass: A Portrait of Philip in Twelve Parts (2007); directed by Scott Hicks

Awards and nominations

Golden Globe Awards

Best Original Score

- Nominated: Kundun (1997)

- Won: The Truman Show (1998)

- Nominated: The Hours (2002)

Academy Awards

Best Original Score

- Nominated: Kundun (1997)

- Nominated: The Hours (2002)

- Nominated: Notes on a Scandal (2006)

Other

- Musical America Musician of the Year (1985)[141]

- Member of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France) – Chevalier (1995)[142]

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Department of Music (2003)[143]

- Classic Brit Award for Contemporary Composer of the Year (The Hours) (2004)[144]

- Critics' Choice Award for Best Composer – The Illusionist (2007)[145]

- 18th International Palm Springs Film Festival Award (2007)[146]

- Fulbright Lifetime Achievement Award Laureate (2009)[147]

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (2009)[148]

- American Classical Music Hall of Fame (2010)[149]

- NEA Opera Honors Award (2010)[150]

- Praemium Imperiale (2012)[151]

- Dance Magazine Award (2013)[152]

- Honorary Doctor of Music, Juilliard School (2014)[153]

- Louis Auchincloss Prize presented by the Museum of the City of New York (2014)[154]

- Eleventh Glenn Gould Prize Laureate (2015)[155]

- National Medal of Arts (2015)[156]

- Chicago Tribune Literary Award (for memoir Words Without Music) (2016)[157]

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Music in a Play – The Crucible (2016)[158]

- Carnegie Hall (New York) 2017–2018 Richard and Barbara Debs Composer's Chair (2017)[159]

- Hollywood Music in Media Awards Best Original Documentary Score – Jane (2017)[160]

- The Society of Composers & Lyricists (SCL) Lifetime Achievement Award (2017)[161]

- 11th Annual Cinema Eye Honors Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Score – Jane (2018)[162]

- Grand Prix France Music Muses Award (for memoir Words Without Music) (2018)

- Kennedy Center Honors (2018)[163]

- Recording Academy Trustees Award (2020)[164]

- ASCAP Television Theme of the Year, Tales from the Loop, co-composer Paul Leonard-Morgan (2021)[165]

- BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award 14th Edition (2022)[166]

Bibliography

See also

- List of ambient music artists

References

- Naxos Classical Music Spotlight podcast: Philip Glass Heroes Symphony

- "The Most Influential People in Classical and Dance", New York, May 8, 2006, retrieved November 10, 2008

- O'Mahony, John (November 24, 2001), "The Guardian Profile: Philip Glass", The Guardian, London, retrieved November 10, 2008

- SPIN Media LLC (May 1985). SPIN. SPIN Media LLC. pp. 55–. ISSN 0886-3032.

- Biography, PhilipGlass.com, archived from the original on August 4, 2013, retrieved November 10, 2008,

The new musical style that Glass was evolving was eventually dubbed "minimalism". Glass himself never liked the term and preferred to speak of himself as a composer of "music with repetitive structures". Much of his early work was based on the extended reiteration of brief, elegant melodic fragments that wove in and out of an aural tapestry.

- Smith, Ethan, "Is Glass Half Empty?", New York, retrieved November 10, 2008

- Smith, Steve (September 23, 2007), "If Grant Had Been Singing at Appomattox", The New York Times

- "Philip Morris Glass". grandsballets.com. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- Scott Hicks (2007). Glass: A Portrait of Philip in Twelve Parts. Event occurs at 33:20.

- Contemporary Authors. New Revision Series. Vol. 131 (Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2005):169–180.

- "Philip Glass Biography – Facts, Birthday, Life Story". Biography.com. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "Philip Glass Biography (1937–)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- John O'Mahony (November 24, 2001). "When less means more". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Joe Staines (2010). The Rough Guide to Classical Music. Penguin. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4053-8321-9. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- Maddocks, Fiona (April 26, 2015). "Words Without Music review – Philip Glass's deft, quietly witty memoir". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- Glass, Philip. Words Without Music: A Memoir, New York: W. W. Norton. (2016) ISBN 1-63149-143-1

- "Composer Philip Glass's Childhood Gig". The Wall Street Journal. May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- Gordinier, Jeff (March 2008), "Wiseguy: Philip Glass Uncut", Details, archived from the original on August 9, 2014, retrieved November 10, 2008

- "Philip Glass on making music with no frills", The Independent, London, June 29, 2007, archived from the original on August 25, 2011, retrieved November 10, 2008

- Skipworth, Mark (January 31, 2011). "Philip Glass shows no signs of easing up". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- "Philip Glass, winner of 2016 Tribune Literary Award, reflects on a life well composed" by John von Rhein, Chicago Tribune, October 26, 2016

- Schwarz 1996, p.

- Jonathan Cott, "Conversation Philip Glass on La Belle et la Bête, booklet notes to the recording, Nonesuch 1995

- Ev Grimes: "Interview: Education" in Kostelanetz 1999, p. 25

- Potter 2000, p. 253.

- Kostelanetz 1999, p. 109.

- Wroe, Nicholas (October 13, 2007). "Play it again ..." The Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Glass, Philip (1985), Music by Philip Glass, New York: DaCapo Press, p. 14, ISBN 0-06-015823-9

- Potter 2000, pp. 266–269

- Potter 2000, p. 255.

- Potter 2000, pp. 257–258.

- Joan La Barbara: "Philip Glass and Steve Reich: Two from the Steady State School" in Kostelanetz 1999, pp. 40–41

- Richard Serra, Writings Interviews, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994, p. 7

- Potter 2000, p. 277.

- "Philip Glass: Composer and...Taxi Driver?". Interlude.hk. September 26, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Glass in conversation with Chuck Close and William Bartman, in, Joanne Kesten (ed.), The Portraits Speak: Chuck Close in conversation with 27 of his subjects, A.R.T. Press, New York, 1997, p. 170

- Potter 2000, p. 252.

- Potter 2000, p. 340.

- Tim Page, booklet notes to the album Einstein on the Beach, Nonesuch 1993

- Booklet notes to the recording Early Voice, Orange Mountain Music, 2002

- Tim Page: "Music in 12 Parts" in Kostelanetz 1999, p. 98

- Tim Page, liner notes to the recording of Einstein on the Beach, Nonesuch Records 1993

- Kostelanetz 1999, p. 58.

- Steffen Schleiermacher, booklet notes to his recording of Glass's "Early Keyboard Music", MDG Records, 2001

- Potter 2000, p. 260.

- Kostelanetz 1999, p. 269.

- David Wright, booklet notes to the first recording of the opera, released on Nonesuch Records, 1999

- Schwarz 1996, p. 151.

- Seabrook, John (March 20, 2006). "Glass's Master Class". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- Stetson, Greta. "Philip Glass wishes he had time to take a four-hour hike". watchnewspapers.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013.

- Philip Glass, booklet notes to the Album Symphony No. 8, Orange Mountain Music, 2006

- Johnson, Lawrence A. (February 9, 2008), "Singers Distinguish Themselves for Visitor", Miami Herald, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Booklet notes by Jody Dalton to the album Solo Piano, CBS, 1989

- Booklet notes by Philip Glass to the album "Music from the Screens", Point Music, 1993

- "But Is it Music?". In Their Own Words; 20th-Century Composers. Episode 2. March 21, 2014. BBC.

- Maycock 2002, p. 71.

- Booklet notes by Philip Glass to the album Low Symphony, Point Music, 1993

- Booklet notes by Philip Glass to the album Symphony No. 2, Nonesuch, 1998

- Booklet notes by Philip Glass to the album Symphony No. 3, Nonesuch, 2000

- Maycock 2002, p. 90.

- Booklet notes by Oliver Binder to "American Piano music", Initativkreis Ruhr/Orange Mountain Music 2009

- Paul Barnes in his booklet notes to the album "The Orphée Suite for Piano, Orange Mountain Music, 2003

- Clements, Andrew (June 2, 2005), "Orphée", The Guardian, London, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Zwiebach, Michael (October 7, 2006), "Arrested Development", San Francisco Classical Voice, archived from the original on September 21, 2008, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Philip Glass, booklet notes to the 1996/1997 recording of Les Enfants terribles, Orange Mountain Music, 2005

- "Concerto for Cello and Orchestra on ChesterNovello website". Chesternovello.com. May 31, 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Jillon Stoppels Dupree, Liner Notes to the album Concerto Project Vol.II, Orange Mountain, 2006

- Philip Glass, notes to the premiere recording of "Waiting for the Barbarians, Orange Mountain Music 2008

- "Entertainment | Philip Glass opera gets ovation". BBC News. September 12, 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Scheinin, Richard (October 7, 2007), "Philip Glass's Appomattox Unremitting, Unforgiving", San Jose Mercury News

- Allan Kozinn, "A First Hearing for a Glass Symphony," The New York Times, November 4, 2005

- Ross, Alex (November 5, 2007), "The Endless Scroll", The New Yorker, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Timothy Mangan, "A stellar premiere", Orange County Register, September 18, 2006

- Mark Swed, "Taking a sounding of the Segerstrom", Los Angeles Times, September 18, 2006

- Hirsch, Lisa (September 28, 2007), "Chambered Glass", San Francisco Classical Voic, archived from the original on June 16, 2008, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Midgette, Anne (March 9, 2008), "New CDs From Musicians Who Play the Field", The Washington Post, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Nico Muhly, "There will be people who are horrified by these ideas", The Guardian, May 22, 2009

- Brantley, Ben (December 19, 2007), "'Beckett Shorts'; When a Universe Reels, A Baryshnikov May Fall", The New York Times, retrieved November 11, 2008

- Corrina da Fonseca-Wollheim,"Where Music Meets Science", The Wall Street Journal, November 24, 2009

- "Culture Monster". Los Angeles Times. November 19, 2009.

- London Philharmonic Orchestra (April 17, 2010). "London Philharmonic Orchestra April 17, 2010". Shop.lpo.org.uk. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Linda Matchan, "Glass's music keeps films moving", Boston Globe, January 11, 2009

- "Maria Bachmann Schedule". Mariabachmann.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- "Glass Notes: Interviews From Tasmania". Philipglass.typepad.com. January 21, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- La Rocco, Claudia (May 5, 2011). "Dance". The New York Times.

- "Culture Monster". Los Angeles Times. February 25, 2011.

- "Philip Glass talks about his Carmel Valley festival this summer and hoped-for Big Sur center". San Jose Mercury News. April 26, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- "American Composers Orchestra – Tuesday, January 31, 2012". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Purvis, Bronwyn (January 21, 2011). "Music is a place; Philip Glass in Hobart – ABC Hobart". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Kevin Smith, Glass's Players Warm Up for a Festival in August, The New York Times, June 13, 2011

- Ayala, Ted (April 9, 2012). "LAPO and John Adams perform West coast premiere of Philip Glass' Symphony No. 9". Bachtrack. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- "Philip Glass 'Symphony No. 9' at PhilipGlass.com". PhilipGlass.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Philip Glass The Perfect American at Chester Novello Music". ChesterNovello.com. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Philip Glass' The Perfect American to Open in Madrid". HuffPost. February 10, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Philip Glass Disney opera to get UK premiere at ENO". BBC. April 24, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Repertoire & Gallery 2017 – The Perfect American". Long Beach Opera. January 30, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- "Konzertprogramm" | Klavier-Festival Ruhr | Düsseldorf | Museum Kunstpalast | Robert-Schumann-Saal | 28. Juni 2013 | (printed program, German)

- "Angélique Kidjo, l'Afrique et l'orchestre". Le Monde.fr. Le Monde. January 17, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- Glass, Philip (2015). Words Without Music. Liveright. ISBN 978-0-87140-438-1.

- Bruckner Orchestra Linz – Celebrating Philip Glass's 80th Birthday, Carnegie Hall, January 31, 2017

- Symphony No. 11, philipglass.com

- "Dinnerstein brings a personal touch to Glass concerto premiere". New York Classical Review. September 29, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- "Philip Glass and L.A. Phil's Fantastic Voyage Through the Music of David Bowie and Brian Eno". LA Weekly. January 14, 2019. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Roy, Sanjoy (July 15, 2019). "Tao of Glass review – golden odyssey through Philip Glass's music". The Guardian. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- McKoen, Belinda (June 28, 2008), "The Sound of Glass", The Irish Times, retrieved November 10, 2008 (subscription required)

- Tim Page, Liner Notes to the album "Music with Changing Parts, Nonesuch Music, 1994

- "Music: Ignorant Sky". Philip Glass. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- "Music: Film: Bent". Philip Glass. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- "Music: Planctus". Philip Glass. February 17, 1997. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- "S'Express on ecstasy, acid house and why drag is the new punk". The Guardian. May 19, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Glass, Phillip; Foster, Fredericka; Jacobs, Beth (June 4, 2018). "The Smaller the Theater, the Faster the Music Composer, Philip Glass talks time with painter Fredericka Foster". nautil.us. Nautilus: Science Connected. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- Glass, Philip; Foster, Fredericka (Fall 2021). "Music, Meditation, Painting—and Dreaming, A conversation with Philip Glass and Fredericka Foster". Tricycle. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- Episode 6006 (1/12/2010), NoFactZone.net, January 13, 2010, archived from the original on July 5, 2011, retrieved May 24, 2010

- Allan Kozinn (June 8, 2012). "Electronic Woe: The Short Lives of Instruments". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "Meet Phillip Glass". Smithsonianmag.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "Music: North Star". Dunvagen Music Publishers. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "Philip Glass: Music: Dance Nos. 1–5". Dunvagen Music Publishers. October 19, 1979. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Philip Glass (January 31, 1937). "Philip Glass – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Butler, Isaac (March 16, 2018)."Errol Morris on His Movie—and Long Friendship—With Stephen Hawking," Slate, retrieved July 30, 2018.

- Deborah Crisp; Roger Hillman (2010). "Chiming the Hours: A Philip Glass Soundtrack". Music and the Moving Image. 3 (2): 30. doi:10.5406/musimoviimag.3.2.0030. ISSN 2167-8464.

- "The Moustache: Movie Review". Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Storm, Jo (2007). Frak you! : the ultimate unauthorized guide to Battlestar Galactica. Toronto: ECW Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-55022-789-5. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- "Scores on Screen. Piano Lessons: Death and Desire in Park Chan-wook's "Stoker" on Notebook". MUBI. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "Hear Philip Glass' 'Duet' From Park Chan-wook's Psycho-Sexual Thriller 'Stoker'". spinmedia.com. February 12, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- Walters, John (February 18, 2016). "Philip Glass Menagerie: The Composer on 26 Years of the Tibet House Benefit Concert". Newsweek. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- Glass, Philip. "Meat: To Eat It or Not". tricycle.org/. Tricycle Foundation. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- The International Who's Who, 1997–98 (61st ed.). Europa Publications. 1997. ISBN 978-1-85743-022-6. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Coe, Robert (October 25, 1981). "Philip Glass Breaks Through". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- Star, Cathalena E. Burch Arizona Daily. "The musical romance of Wendy Sutter and Philip Glass". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Q&A With Composer Philip Glass and His Girlfriend, Wendy Sutter – Heart of Glass" by Rebecca Milzoff, New York, January 31, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Sheridan, Wade (December 3, 2018). "Reba McEntire, Cher lauded at Kennedy Center Honors". UPI. See caption for photo 8/57. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Photo: Composer Philip Glass arrives for Kennedy Center Honors Gala in Washington DC - WAP20181202508". UPI. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- Solomon, Deborah (March 4, 2007). "This American TV Show". The New York Times. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Ira Glass (June 20, 2014). "The Radio Drama Episode". This American Life (Podcast). Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- Wise Music Classical: Philip Glass, Musical Opinion by Christopher Monk

- Philip Glass Composer Archived May 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine The National Endowment for the Arts: 2010 Opera Honors

- Philip Glass: Akhnaten Classical Music Review: New Releases

- "Had I Never Listened Closely Enough?". NYMag.com. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Schickel, Richard (December 23, 2002). "Holiday Movie Preview: The Hours". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on November 23, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Cited at Richard Guerin (April 20, 2010). "'Classic art' ... "This new concerto is unmitigated trash."". philipglass.com. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- "About us: Musical America Award winners". Musical America. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Berry, Heather (December 18, 1998). ""Monsters of Grace 4.0" By Philip Glass and Robert Wilson Returns to UCLA March 30 In New, Fully Animated Format". UCLA newsroom. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "About us: Musical America Award winners". Arts And Letters. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Brandle, Lars (June 12, 2004). "News Line". Billboard. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Repstad, Laura (January 12, 2007). "Critics choose 'Departed'". Variety. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Schreiber, Brad (January 18, 2007). "Cinema blossoms in the desert". Entertainment Today. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- "The Fulbright Lifetime Achievement Award". Fulbright Association. 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 23, 2021.