Foreskin

The foreskin, also known as the prepuce, is the double-layered fold of skin, mucosal, and muscular tissue that covers the glans penis and urinary meatus.[lower-alpha 1][3]

| Foreskin | |

|---|---|

Foreskin fully covering the glans penis | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, urogenital folds |

| Artery | Dorsal artery of the penis |

| Vein | Dorsal veins of the penis |

| Nerve | Dorsal nerve of the penis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Praeputium |

| MeSH | D052816 |

| TA98 | A09.4.01.011 |

| TA2 | 3675 |

| FMA | 19639 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

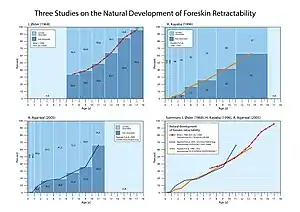

In humans, foreskin length varies widely, and coverage of the glans in a flaccid and erect state varies.[4] The foreskin is fused to the glans at birth and is generally not retractable in infancy or early childhood. Inability to retract the foreskin in childhood should not be considered a problem unless there are other symptoms.[5] Retraction of the foreskin is not recommended before it loosens from the glans.[5] In adults, it is typically retractable over the glans, given normal development.[5] The foreskin may become subject to a number of pathological conditions, such as phimosis, balanitis, and posthitis, although most of these are easily treatable.[6]

Structure

The outside of the foreskin is a continuation of the skin on the shaft of the penis, but the inner foreskin is a mucous membrane like the inside of the eyelid or the mouth. The mucocutaneous zone occurs where the outer and inner foreskin meet. Like the eyelid, the foreskin is free to move after it separates from the glans, which usually occurs before or during puberty. The foreskin is attached to the glans by a frenulum, a highly vascularized tissue of the penis.[7] The World Health Organization states that "[t]he frenulum forms the interface between the outer and inner foreskin layers, and when the penis is not erect, it tightens to narrow the foreskin opening.[7] The human foreskin contains a sheath of muscle tissue just below the skin, formerly known as the peripenic muscle and now called the dartos fascia; elastic fibers are contained in the dartos fascia.[8] The dartos fascia is sensitive to temperature and expands and contracts with temperature changes.[9] The dartos fascia is only loosely connected with the underlying tissue so it provides the skin mobility and elasticity of the penile skin.[8] Langerhans cells are immature dendritic cells that are found in all areas of the penile epithelium,[10] but are most superficial in the inner surface of the foreskin.[10]

The area of the outer foreskin measures 7–100 cm2,[11] and the inner foreskin measures 18–68 cm.2[4]

In 1996, following a study of 22 cadavers, retired pathologist John Taylor published a paper in which he proposed that the pleated skin of the distal foreskin was a distinct anatomical structure that played an important role in sexual function.[12][13][14] A 2015 review by Cox and colleagues said that the feature was particular to some men and that his illustrations had been inconsistent.[15]

Development

The foreskin is present in the vast majority of mammals, including non-human primates, such as the chimpanzee.[7]

In children, the foreskin usually covers the glans completely but in adults it may not. During erection, the degree of automatic foreskin retraction varies considerably; in some adults, the foreskin remains covering all or some of the glans until retracted manually or by sexual activity. This variation was regarded by Chengzu (2011) as an abnormal condition named 'prepuce redundant'. Frequent retraction and washing under the foreskin is suggested for all adults but particularly for those with a long, or 'redundant' foreskin.[16] When the foreskin is longer than the erect penis, it will not spontaneously retract upon erection. Some males, according to Xianze (2012), may be reluctant for their glans to be exposed because of discomfort when it chafes against clothing, although the discomfort on the glans was reported to diminish within one week of continuous exposure.[17] Guochang (2010) states that for those whose foreskins are too tight to retract or have some adhesions, forcible retraction should be avoided since it may cause injury.[18]

Function

There is significant debate within the literature about potential functions of the foreskin, its frequent prophylactic removal in circumcision, and whether it should be classified as a vestigal organ.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) stated in 2007 that there was "debate about the role of the foreskin, with possible functions including keeping the glans moist, protecting the developing penis in utero, or enhancing sexual pleasure due to the presence of nerve receptors".[7] The foreskin helps to provide sufficient skin during an erection. The foreskin protects the glans.[20] In infants, it protects the glans from ammonia and feces in diapers, which reduces the incidence of meatal stenosis. And the foreskin helps prevent the glans from getting abrasions and trauma throughout life. The fold of the prepuce produces sub-preputial wetness, helping to maintain the naturally moisturized state of the glans penis. The foreskin contains Meissner's corpuscles, which are nerve endings involved in fine-touch sensitivity. A study of skin samples found that, compared to other hairless skin areas on the body, the Meissner's index was highest in the finger tip (0.96) and lowest in the foreskin (0.28) suggested that the foreskin has the least sensitive hairless tissue of the body.[15]

Evolution

In primates, the foreskin is present in the genitalia of both sexes and likely has been present for millions of years of evolution.[21] The evolution of complex penile morphologies like the foreskin may have been influenced by females.[22][23][24]

In modern times, there is controversy regarding whether the foreskin is a vital or vestigial structure.[1] In 1949, British physician Douglas Gairdner noted that the foreskin plays an important protective role in newborns. He wrote, "It is often stated that the prepuce is a vestigial structure devoid of function... However, it seems to be no accident that during the years when the child is incontinent the glans is completely clothed by the prepuce, for, deprived of this protection, the glans becomes susceptible to injury from contact with sodden clothes or napkin."[1] During the physical act of sex, the foreskin reduces friction, which can reduce the need for additional sources of lubrication.[1] The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia has written that the foreskin is "composed of an outer skin and an inner mucosa that is rich in specialized sensory nerve endings and erogenous tissue."[20] However, "some medical researchers, however, claim circumcised men enjoy sex just fine and that, in view of recent research on HIV transmission, the foreskin causes more trouble than it’s worth."[1] In the March 2017 publication of the Global Health Journal: Science and Practice, Morris and Krieger wrote, "The variability in foreskin size is consistent with the foreskin being a vestigial structure."[2]

Clinical significance

The foreskin can be involved in balanitis, phimosis, sexually transmitted infection and penile cancer.[25] The American Academy of Pediatricians' 2012 technical report on circumcision found that the foreskin tends to harbor micro-organisms that can lead to urinary tract infections in infants and tend to contribute to the transmission of sexually transmitted infections in adults.[26]

Frenulum breve is a frenulum that is insufficiently long to allow the foreskin to fully retract, which may lead to discomfort during intercourse.

Phimosis is a condition where the foreskin of an adult cannot be retracted properly. Phimosis can be treated by using topical steroid ointments and using lubricants during sex; for severe cases circumcision may be necessary.[27] Posthitis is an inflammation of the foreskin.

A condition called paraphimosis may occur if a tight foreskin becomes trapped behind the glans and swells as a restrictive ring. This can cut off the blood supply, resulting in ischemia of the glans penis.[27]

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that most commonly occurs in adult women, although it may also be seen in men and children. Topical clobetasol propionate and mometasone furoate were proven effective in treating genital lichen sclerosus.[28]

Some birth defects of the foreskin can occur; all of them are rare. In aposthia there is no foreskin at birth,[29]: 37–39 in micropathia the foreskin does not cover the glans,[29]: 41–45 and in macroposthia, also called and congenital megaprepuce, the foreskin extends well past the end of the glans.[29]: 47–50

It has been found that larger foreskins place uncircumcised men at an increased risk for HIV infection[30] most likely due to the larger surface area of inner foreskin and the high concentration of Langerhans cells.[31]

Society and culture

Modifications

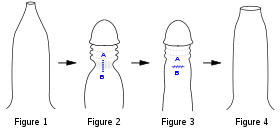

Fig 1. Penis with tight phimotic ring making it difficult to retract the foreskin.

Fig 2. Foreskin retracted under anaesthetic with the phimotic ring or stenosis constricting the shaft of the penis and creating a "waist".

Fig 3. Incision closed laterally.

Fig 4. Penis with the loosened foreskin replaced over the glans.

Circumcision is the removal of the foreskin, either partially or completely. For newborns, it may be done for religious requirements or personal preferences surrounding hygiene and aesthetics.[32]: 257 Circumcision may also be performed on children or adults to treat phimosis, balanitis, or to prevent transmission of sexually transmitted infections.[33]: 166 The ethics of circumcision in children is a source of controversy.[34][35][36] As of 2012, no successful technique to reconstruct a circumcised foreskin had been published.[37]: 181 Some men have used weights to stretch the skin of the penis to regrow a foreskin; the resulting tissue does cover the glans but does not replicate the features of a foreskin.[38]

Other cultural or aesethetic practices include genital piercings involving the foreskin and slitting the foreskin.[39]

Preputioplasty is the most common foreskin reconstruction technique, most often done when a boy is born with a foreskin that is too small;[37]: 177 a similar procedure is performed to relieve a tight foreskin without resorting to circumcision.[37]: 181

Foreskin restoration and regeneration

Foreskin restoration is the process of expanding the skin on the penis to reconstruct an organ similar to the foreskin, which has been removed by circumcision or injury.[40] Foreskin restoration is of ancient origin, when surgical means were taken to lengthen the foreskin of individuals born with either a short foreskin that did not cover the glans completely[41] or a completely exposed glans as a result of circumcision.[42] Foreskin restoration has been reported as having beneficial emotional results in some men, and has been proposed as a treatment for feelings of sexual violation or mutilation in adult men for circumcisions that were performed on them without consent.[43]

Foreskin restoration is primarily accomplished by stretching the residual skin of the penis, but surgical methods also exist. Some forms of restoration involve only partial regeneration in instances of a high-cut wherein the circumcisee feels that the circumciser removed too much skin and that there is not enough skin for erections to be comfortable.[40] Restoration creates a facsimile of the foreskin, but specialized tissues removed during circumcision such as the ridged band and frenulum cannot be reclaimed. Actual regeneration of the foreskin is experimental at this time.[44]

Foreskin-based products

Foreskins obtained from circumcision procedures are frequently used by biochemical and micro-anatomical researchers to study the structure and proteins of human skin. In particular, foreskins obtained from newborns have been found to be useful in the manufacturing of more human skin.[45]

Foreskins of babies are also used for skin graft tissue,[46][47][48] and for β-interferon-based drugs.[49]

Foreskin-derived fibroblasts have been used in biomedical research,[50] and cosmetic applications.[51]

Sexual practices

The foreskin plays a role in the sexual practice of docking. Docking is a gay sexual practice, which involves mutual masturbation, by inserting the glans penis into the foreskin of another penis.

History

Foreskin was considered a sign of beauty, civility, and masculinity throughout the Greco-Roman world.[52] In ancient Greece, foreskins were valued, especially those that were longer in length.[53] The earliest known illustrative depiction of the foreskin dates back to Egyptian kingdoms.[54]

The foreskin has also been depicted in art from different historical ages:

David Marble sculpture, 1504 A.D.

David Marble sculpture, 1504 A.D. "Orestes at Delphi". Painting of two naked males, ca. 330 B.C.

"Orestes at Delphi". Painting of two naked males, ca. 330 B.C. The Marathon Youth, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, ca. 340-330 B.C.

The Marathon Youth, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, ca. 340-330 B.C.

Notes

- There is controversy regarding whether the foreskin is vestigal organ or functional. Some sources have described circumcision as protecting the glans, although others have disputed this contention.[1][2]

References

- Collier R (November 2011). "Vital or vestigial? The foreskin has its fans and foes". CMAJ. 183 (17): 1963–1964. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4014. PMC 3225416. PMID 22025652.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN, Klausner JD (March 2017). "CDC's Male Circumcision Recommendations Represent a Key Public Health Measure". Global Health: Science and Practice. 5 (1): 15–27. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00390. PMC 5478224. PMID 28351877.

- Kirby R, Carson C, Kirby M (2009). Men's Health (3rd ed.). New York: Informa Healthcare. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4398-0807-8. OCLC 314774041.

- Werker PM, Terng AS, Kon M (September 1998). "The prepuce free flap: dissection feasibility study and clinical application of a super-thin new flap". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 102 (4): 1075–1082. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809040-00024. PMID 9734426. S2CID 37976399.

- Potts, Jeannette (2004). "Penis Problems". Essential Urology: A Guide to Clinical Practice. Humana Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781592597376.

Virtually all foreskins become retractable in puberty. Thus, phimosis is not a pathological condition in young children unless it is associated with balanitis, or, rarely, urinary retention.

- Shah M (January 2008). The Male Genitalia: A Clinician's Guide to Skin Problems and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-84619-040-7. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Hadidi, Ahmed (2022). Hypospadias Surgery: An Illustrated Textbook. Springer. pp. 115, 624. ISBN 9783030942489.

- Gibson, Alan; Akinrinsola, Adetokunbo; Patel, Tejesh; Ray, Arijit; Tucker, John; McFadzean, Ian (August 2002). "Pharmacology and thermosensitivity of the dartos muscle isolated from rat scrotum". British Journal of Pharmacology. 136 (8): 1194–1200. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704830. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 1573456. PMID 12163353.

- McCoombe SG, Short RV (July 2006). "Potential HIV-1 target cells in the human penis". AIDS. 20 (11): 1491–1495. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000237364.11123.98. PMID 16847403. S2CID 22839409.

- Kigozi G, Wawer M, Ssettuba A, Kagaayi J, Nalugoda F, Watya S, et al. (October 2009). "Foreskin surface area and HIV acquisition in Rakai, Uganda (size matters)". AIDS. 23 (16): 2209–2213. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330eda8. PMC 3125976. PMID 19770623.

- Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ (February 1996). "The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision". British Journal of Urology. 77 (2): 291–295. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.1996.85023.x. PMID 8800902. Archived from the original on 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Baky Fahmy MA (2020). Normal and Abnormal Prepuce. Springer Nature. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-030-37621-5. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- Milne C (December 5, 2000). "The Circumcision Debate". The Globe And Mail. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- Cox G, Krieger JN, Morris BJ (June 2015). "Histological Correlates of Penile Sexual Sensation: Does Circumcision Make a Difference?". Sexual Medicine. 3 (2): 76–85. doi:10.1002/sm2.67. PMC 4498824. PMID 26185672.

- Chengzu L (2011). "Health Care for Foreskin Conditions". Epidemiology of Urogenital Diseases. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- Xianze L (2012). Tips on Puberty Health. Beijing: People's Education Press.

- Guochang H (2010). General Surgery. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- College of Physicians; Surgeons of British Columbia (2009). "Circumcision (Infant Male)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- Martin RD (1990). Primate Origins and Evolution: A Phylogenetic Reconstruction. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08565-4.

- Diamond JM (1997). Why Sex is Fun: The Evolution of Human Sexuality. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-465-03126-9.

- Darwin C (1871). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: Murray. ISBN 978-1-148-75093-4.

- Short RV (1981). "Sexual selection in man and the great apes". In Graham CE (ed.). Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes: Comparative and Biomedical Perspectives. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 9780323149716. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- Simmons MN, Jones JS (May 2007). "Male genital morphology and function: an evolutionary perspective". The Journal of Urology. 177 (5): 1625–1631. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.011. PMID 17437774.

- Blank, Susan; Brady, Michael; Buerk, Ellen; Carlo, Waldemar; Diekema, Douglas; Freedman, Andrew; Maxwell, Lynne; Wegner, Steven (September 2012). "Male circumcision". Pediatrics. 130 (3): e756–e785. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1990. PMID 22926175.. The technical report was published in conjunction with an updated statement of policy on circumcision: Blank, Susan; Brady, Michael; Buerk, Ellen; Carlo, Waldemar; Diekema, Douglas; Freedman, Andrew; Maxwell, Lynne; Wegner, Steven (September 2012). "Circumcision policy statement" (PDF). Pediatrics. 130 (3): 585–586. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1989. PMID 22926180. S2CID 207166111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- "Phimosis (tight foreskin)". NHS Choices. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Chi CC, Kirtschig G, Baldo M, Brackenbury F, Lewis F, Wojnarowska F (December 2011). "Topical interventions for genital lichen sclerosus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008240. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008240.pub2. PMC 7025763. PMID 22161424.

- Fahmy M (2017). Congenital Anomalies of the Penis – Springer. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-43310-3.

- Van Howe RS, Sorrells MS, Snyder JL, Reiss MD, Milos MF (December 2016). "Letter from Van Howe et al Re: Examining Penile Sensitivity in Neonatally Circumcised and Intact Men Using Quantitative Sensory Testing: J. A. Bossio, C. F. Pukall and S. S. Steele J Urol 2016;195:1848-1853". The Journal of Urology. 196 (6): 1824. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.127. PMID 28181790.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ. 320 (7249): 1592–1594. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Cox G, Morris BJ (2012). "Chapter 21: Why Circumcision:From Prehistory to the Twenty-First Century". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 243–259. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- McClung C, Voelzke B (2012). "Chapter 14: Adult Circumcision". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 165–175. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- Boyle GJ, Svoboda JS, Price CP, Turner JN (2000). "Circumcision of healthy boys: Criminal assault?". Journal of Law and Medicine. 7: 301–310.

- "Policy Statement On Circumcision". Royal Australasian College of Physicians. September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

The Paediatrics and Child Health Division, The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) has prepared this statement on routine circumcision of infants and boys to assist parents who are considering having this procedure undertaken on their male children and for doctors who are asked to advise on or undertake it. After extensive review of the literature the RACP reaffirms that there is no medical indication for routine neonatal circumcision. Circumcision of males has been undertaken for religious and cultural reasons for many thousands of years. It remains an important ritual in some religious and cultural groups.…In recent years there has been evidence of possible health benefits from routine male circumcision. The most important conditions where some benefit may result from circumcision are urinary tract infections, HIV and later cancer of the penis.…The complication rate of neonatal circumcision is reported to be around 1% and includes tenderness, bleeding and unhappy results to the appearance of the penis. Serious complications such as bleeding, septicaemia and may occasionally cause death (1 in 550,000). The possibility that routine circumcision may contravene human rights has been raised because circumcision is performed on a minor and is without proven medical benefit. Whether these legal concerns are valid will be known only if the matter is determined in a court of law. If the operation is to be performed, the medical attendant should ensure this is done by a competent operator, using appropriate anaesthesia and in a safe child-friendly environment. In all cases where parents request a circumcision for their child the medical attendant is obliged to provide accurate information on the risks and benefits of the procedure. Up-to-date, unbiased written material summarizing the evidence should be widely available to parents. Review of the literature in relation to risks and benefits shows there is no evidence of benefit outweighing harm for circumcision as a routine procedure in the neonate.

- Medical Ethics Committee. British Medical Association. The law and ethics of male circumcision - guidance for doctors; June 2006 [archived 2007-11-12].

- Snodgrass WT (2012). "Chapter 15: Foreskin Reconstruction". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 177–181. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- Collier R (December 2011). "Whole again: the practice of foreskin restoration". CMAJ. 183 (18): 2092–2093. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4009. PMC 3255154. PMID 22083672.

- "Paraphimosis : Article by Jong M Choe, MD, FACS". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- Lerman SE, Liao JC (December 2001). "Neonatal circumcision". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 48 (6): 1539–1557. doi:10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70390-4. PMID 11732129.

-

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

— Jacob Neusner, Approaches to Ancient Judaism, New Series: Religious and Theological Studies (1993), p. 149, Scholars Press. - Money J (1991). "Sexology, body image, foreskin restoration, and bisexual status". Journal of Sex Research. Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality. 28 (1): 145–56. doi:10.1080/00224499109551600.

- Boyle GJ, Goldman R, Svoboda JS, Fernandez E (May 2002). "Male circumcision: pain, trauma and psychosexual sequelae". Journal of Health Psychology. 7 (3): 329–343. doi:10.1177/135910530200700310. PMID 22114254. S2CID 22036469.

- Purpura V, Bondioli E, Cunningham EJ, De Luca G, Capirossi D, Nigrisoli E, et al. (January 2018). "The development of a decellularized extracellular matrix-based biomaterial scaffold derived from human foreskin for the purpose of foreskin reconstruction in circumcised males". Journal of Tissue Engineering. 9: 2041731418812613. doi:10.1177/2041731418812613. PMC 6304708. PMID 30622692.

- McKie R (1999-04-04). "Foreskins for Skin Grafts". The Toronto Star.

- "High-Tech Skinny on Skin Grafts". 1999-02-16. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Grand DJ (August 15, 2011). "Skin Grafting". Medscape. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- Amst C, Carey J (July 27, 1998). "Biotech Bodies". www.businessweek.com. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Cowan AL (April 19, 1992). "Wall Street; A Swiss Firm Makes Babies Its Bet". New York Times:Business. Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Hovatta O, Mikkola M, Gertow K, Strömberg AM, Inzunza J, Hreinsson J, et al. (July 2003). "A culture system using human foreskin fibroblasts as feeder cells allows production of human embryonic stem cells". Human Reproduction. 18 (7): 1404–1409. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg290. PMID 12832363.

- Malamut M (14 April 2015). "The 'Baby Foreskin Facial' Is a Real Thing". Boston Magazine.

- Hall, Robert (August 1992). "Epispasm: Circumcision in Reverse". Bible Review. 8 (4): 52–57.

- Hodges FM (2001). "The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (3): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. JSTOR 44445662. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193.

- Raveenthiran V (2020). "History of the Prepuce". Normal and Abnormal Prepuce. Springer. pp. 7–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_2. ISBN 978-3-030-37620-8. S2CID 216446879.

External links

- Infant foreskin care at Kidshealth.org.nz

- "Care for an Uncircumcised Penis". Healthy Children. American Academy of Pediatrics. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Management of foreskin conditions Archived 2014-04-06 at the Wayback Machine – Statement from the British Association of Paediatric Urologists on behalf of the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons and The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists (2007).