Phimosis

Phimosis (from Greek φίμωσις phimōsis 'muzzling'.[9][10][11]) is a condition in which the foreskin of the penis cannot stretch to allow it to be pulled back past the glans.[3] A balloon-like swelling under the foreskin may occur with urination.[3] In teenagers and adults, it may result in pain during an erection, but is otherwise not painful.[3] Those affected are at greater risk of inflammation of the glans, known as balanitis, and other complications.[3]

| Phimosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| An erect penis with a case of phimosis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Symptoms | Unable to pull the foreskin back past the glans[3] |

| Complications | Balanitis,[3] penile cancer , urinary retention |

| Usual onset | Normal at birth[3] |

| Duration | Typically resolves by 18 years old[4] |

| Causes | Normal, balanitis, balanitis xerotica obliterans[5] |

| Risk factors | Diaper rash, poor cleaning, diabetes[6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Hair tourniquet, lymphedema of the penis[6] |

| Prevention | Steroid cream, stretching exercises, circumcision[7] |

| Frequency | 1%–2% (in uncircumcised males 18 years or older)[8][4] |

In young children, it is normal not to be able to pull back the foreskin at all.[7] Over 90% of cases resolve by the age of seven, although full retraction is still prevented by preputial adhesions in over half at this age.[5][7] Occasionally, phimosis may be caused by an underlying condition such as scarring due to balanitis or balanitis xerotica obliterans.[5] This can typically be diagnosed by seeing scarring of the opening of the foreskin.[5]

Typically, the condition resolves without treatment by the age of 18.[4] Efforts to pull back the foreskin during the early years of a young male's life should not be attempted.[7] For those in whom the condition does not improve further, time can be given or a steroid cream may be used to attempt to loosen the tight skin.[7] If this method, combined with stretching exercises, is not effective, then other treatments such as circumcision may be recommended.[7] A potential complication of phimosis is paraphimosis, where the tight foreskin becomes trapped behind the glans.[5]

Signs and symptoms

At birth, the inner layer of the foreskin is sealed to the glans penis. The foreskin is usually non-retractable in early childhood, and some males may reach the age of 18 before their foreskin can be fully retracted.[12]

Medical associations advise not to retract the foreskin of an infant, in order to prevent scarring.[13][14] Some argue that non-retractability may "be considered normal for males up to and including adolescence."[15][16] Hill states that full retractability of the foreskin may not be achieved until late childhood or early adulthood.[17] A Danish survey found that the mean age of first foreskin retraction is 10.4 years.[18]

Rickwood, as well as other authors, has suggested that true phimosis is over-diagnosed due to failure to distinguish between normal developmental non-retractability and a pathological condition.[19][20][21] Some authors use the terms "physiologic" and "pathologic" to distinguish between these types of phimosis;[22] others use the term "non-retractile foreskin" to distinguish this developmental condition from pathologic phimosis.[19]

In some cases a cause may not be clear, or it may be difficult to distinguish physiological phimosis from pathological phimosis if an infant appears to have discomfort while urinating or demonstrates obvious ballooning of the foreskin. However, ballooning does not indicate urinary obstruction.[23]

In women, a comparable condition is known as "clitoral phimosis", whereby the clitoral hood cannot be retracted, limiting exposure of the glans clitoridis.[24]

Severity

- Score 1: full retraction of foreskin, tight behind the glans.

- Score 2: partial exposure of glans, prepuce (not congenital adhesions) limiting factor.

- Score 3: partial retraction, meatus just visible.

- Score 4: slight retraction, but some distance between tip and glans, i.e. neither meatus nor glans can be exposed.

- Score 5: absolutely no retraction of the foreskin.[25]

Cause

There are three mechanical conditions that prevent foreskin retraction:

-

- The inner surface of the foreskin is fused with the glans penis. This is normal in children and adolescents but abnormal in adults.[27]

-

- The frenulum is too short to allow complete retraction of the foreskin (a condition called frenulum breve).[27]

Pathological phimosis (as opposed to the natural non-retractability of the foreskin in childhood) is rare, and the causes are varied. Some cases may arise from balanitis (inflammation of the glans penis).[28]

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (thought to be the same condition as balanitis xerotica obliterans) is regarded as a common (or even the main)[29] cause of pathological phimosis.[30] This is a skin condition of unknown origin that causes a whitish ring of indurated tissue (a cicatrix) to form near the tip of the prepuce. This inelastic tissue prevents retraction.

Phimosis may occur after other types of chronic inflammation (such as balanoposthitis), repeated catheterization, or forcible foreskin retraction.[31]

Phimosis may also arise in untreated diabetics due to the presence of glucose in their urine giving rise to infection in the foreskin.[32]

Beaugé noted that unusual masturbation practices, such as thrusting against the bed or rubbing the foreskin forward may cause phimosis. Patients are advised to stop exacerbating masturbation techniques and are encouraged to masturbate by moving the foreskin up and down so as to mimic more closely the action of sexual intercourse. After giving this advice Beaugé noted not once did he have to recommend circumcision.[33][34]

Phimosis in older children and adults can vary in severity, with some able to retract their foreskin partially (relative phimosis), while others are completely unable to retract their foreskin, even when the penis is in a flaccid state (full phimosis).

Treatment

Physiologic phimosis, common in males 10 years of age and younger, is normal, and does not require intervention.[26][35][27] Non-retractile foreskin usually becomes retractable during the course of puberty.[27]

If phimosis in older children or adults is not causing acute and severe problems, nonsurgical measures may be effective. Choice of treatment is often determined by whether circumcision is viewed as an option of last resort or as the preferred course.

Nonsurgical

- Patients are advised to stop exacerbating masturbation techniques and are encouraged to masturbate by moving the foreskin up and down so as to mimic more closely the action of sexual intercourse. After giving this advice Beaugé noted not once did he have to recommend circumcision.[33][34]

- Topical steroid creams such as betamethasone, mometasone furoate and cortisone are effective in treating phimosis and should be considered before circumcision.[35][36][37] It is theorized that the steroids work by reducing the body's inflammatory and immune responses, and also by thinning the skin.[35]

- Gently stretching of the foreskin can be accomplished manually. Skin that is under tension expands by growing additional cells. There are different ways to stretch the phimosis. If the opening of the foreskin is already large enough, the foreskin is rolled over two fingers and these are carefully pulled apart. If the opening is still too small, flesh tunnels can be used. These are inserted into the foreskin opening and should preferably be made of silicone so that they can be folded when inserted and so that they do not interfere when worn. The diameter is gradually increased until the foreskin can be retracted without difficulty. Even phimosis with a diameter of less than a millimetre can be stretched with these rings. Rings in different sizes are also available as stretching sets. Studies involving treating phimosis using topical steroids in conjunction with stretching exercises have reported success rates of up to 96%.[36] However, other sources claim "wildly variable reported failure rates (5 – 33 %) and lack of follow-up to adulthood."[38]

Stretching the foreskin opening with two fingers

Stretching the foreskin opening with two fingers Stretching the foreskin opening with flesh tunnel of different diameters

Stretching the foreskin opening with flesh tunnel of different diameters

Surgical

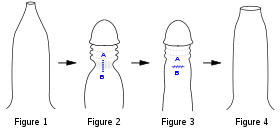

Fig 1. Penis with tight phimotic ring making it difficult to retract the foreskin.

Fig 2. Foreskin retracted under anaesthetic with the phimotic ring or stenosis constricting the shaft of the penis and creating a "waist".

Fig 3. Incision closed laterally.

Fig 4. Penis with the loosened foreskin replaced over the glans.

Surgical methods range from the complete removal of the foreskin to more minor operations to relieve foreskin tightness:

- Dorsal slit (superincision) is a single incision along the upper length of the foreskin from the tip to the corona, exposing the glans without removing any tissue.

- Ventral slit (subincision) is an incision along the lower length of the foreskin from the tip of the frenulum to the base of the glans, removing the frenulum in the process. Often used when frenulum breve occurs alongside the phimosis.

- Preputioplasty, in which a limited dorsal slit with transverse closure is made along the constricting band of skin,[39] can be an effective alternative to circumcision.[21] It has the advantage of only limited pain and a short healing duration relative to circumcision, while also avoiding cosmetic effects.[39]

- Circumcision is sometimes performed for phimosis, and is an effective treatment; however, this method has become less common as of 2012.[12]

While circumcision prevents phimosis, studies of the incidence of healthy infants circumcised for each prevented case of phimosis are inconsistent.[20][31]

Prognosis

The most acute complication is paraphimosis. In this condition, the glans is swollen and painful, and the foreskin is immobilized by the swelling in a partially retracted position. The proximal penis is flaccid. Some studies found phimosis to be a risk factor for urinary retention[40] and carcinoma of the penis.[41]

Epidemiology

A number of medical reports of phimosis incidence have been published over the years. They vary widely because of the difficulties of distinguishing physiological phimosis (developmental nonretractility) from pathological phimosis, definitional differences, ascertainment problems, and the multiple additional influences on post-neonatal circumcision rates in cultures where most newborn males are circumcised. A commonly cited incidence statistic for pathological phimosis is 1% of uncircumcised males.[20][31][42] When phimosis is simply equated with nonretractility of the foreskin after age 3 years, considerably higher incidence rates have been reported.[27][43] Others have described incidences in adolescents and adults as high as 50%, though it is likely that many cases of physiological phimosis or partial nonretractility were included.[44]

History

According to some accounts, phimosis prevented Louis XVI of France from impregnating his wife, Marie Antoinette, for the first seven years of their marriage, but this theory was later discredited.[45] She was 14 and he was 15 when they married in 1770. However, the presence and nature of his genital anomaly is not considered certain, and some scholars (such as Vincent Cronin and Simone Bertiere) assert that surgical repair would have been mentioned in the records of his medical treatments if this had indeed occurred. Non-retractile prepuce in adolescence is normal, common, and usually resolves with increasing maturity.[27]

US president James Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau in 1881. Guiteau's autopsy report indicated that he had phimosis. At the time, this led to the speculation that Guiteau's murderous behavior was due to phimosis-induced insanity.[46]

References

- OED 2nd edition, 1989 as /faɪˈməʊsɪs/.

- Entry "phimosis" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Phimosis". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Natural Foreskin Retraction in Intact Children and Teens". Peaceful Parenting.

- McGregor TB, Pike JG, Leonard MP (March 2007). "Pathologic and physiologic phimosis: approach to the phimotic foreskin". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (3): 445–8. PMC 1949079. PMID 17872680.

- Domino FJ, Baldor RA, Golding J (2013). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2014. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 138. ISBN 9781451188509.

- "What are the treatment options for phimosis?". PubMed Health. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Phimosis". Doctors Opposing Circumcision. 6 July 2016.

- φίμωσις, φιμός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Harper, Douglas. "phimosis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Kirk RH, Winslet MC (2007). Essential General Surgical Operations. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 365. ISBN 978-0443103148. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- Shahid SK (5 March 2012). "Phimosis in children". ISRN Urology. 2012: 707329. doi:10.5402/2012/707329. PMC 3329654. PMID 23002427.

- "Care of the Uncircumcised Penis". Guide for parents. American Academy of Pediatrics. September 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-08-30.

- "Caring for an uncircumcised penis". Information for parents. Canadian Paediatric Society. July 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16.

- Huntley JS, Bourne MC, Munro FD, Wilson-Storey D (September 2003). "Troubles with the foreskin: one hundred consecutive referrals to paediatric surgeons". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 96 (9): 449–51. doi:10.1177/014107680309600908. PMC 539600. PMID 12949201.

- Denniston GC, Hill G (October 2010). "Gairdner was wrong". Canadian Family Physician. 56 (10): 986–7. PMC 2954072. PMID 20944034. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- Hill G (June 2003). "Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys". The Medical Journal of Australia. 178 (11): 587, author reply 589–90. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05368.x. PMID 12765511. S2CID 11588415. Archived from the original on 2008-08-30.

- Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff HH (April 2005). "[Pathological or physiological phimosis?]" (PDF). Ugeskrift for Laeger. 167 (17): 1858–62. PMID 15929334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-07. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- Rickwood AM, Walker J (September 1989). "Is phimosis overdiagnosed in boys and are too many circumcisions performed in consequence?". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 71 (5): 275–7. PMC 2499015. PMID 2802472.

Authors review English referral statistics and suggest phimosis is overdiagnosed, especially in boys under 5 years, because of confusion with developmentally nonretractile foreskin.

- Spilsbury K, Semmens JB, Wisniewski ZS, Holman CD (February 2003). "Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys". The Medical Journal of Australia. 178 (4): 155–8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05130.x. PMID 12580740. S2CID 9842095. Archived from the original on 2004-11-09.. Recent Australian statistics with good discussion of ascertainment problems arising from surgical statistics.

- Van Howe RS (October 1998). "Cost-effective treatment of phimosis". Pediatrics. 102 (4): E43. doi:10.1542/peds.102.4.e43. PMID 9755280. Archived from the original on 2009-08-19. A review of estimated costs and complications of 3 phimosis treatments (topical steroids, praeputioplasty, and surgical circumcision). The review concludes that topical steroids should be tried first, and praeputioplasty has advantages over surgical circumcision. This article also provides a good discussion of the difficulty distinguishing pathological from physiological phimosis in young children and alleges inflation of phimosis statistics for purposes of securing insurance coverage for post-neonatal circumcision in the United States.

- McGregor TB, Pike JG, Leonard MP (March 2007). "Pathologic and physiologic phimosis: approach to the phimotic foreskin". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (3): 445–8. PMC 1949079. PMID 17872680.

- Babu R, Harrison SK, Hutton KA (August 2004). "Ballooning of the foreskin and physiological phimosis: is there any objective evidence of obstructed voiding?". BJU International. 94 (3): 384–7. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04935.x. PMID 15291873. S2CID 32118768.

- Munarriz R, Talakoub L, Kuohung W, Gioia M, Hoag L, Flaherty E, et al. (2002). "The prevalence of phimosis of the clitoris in women presenting to the sexual dysfunction clinic: lack of correlation to disorders of desire, arousal and orgasm". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 28 (Suppl 1): 181–5. doi:10.1080/00926230252851302. PMID 11898701. S2CID 45521652.

- Kikiros CS, Beasley SW, Woodward AA (1993-05-01). "The response of phimosis to local steroid application" (PDF). Pediatric Surgery International. 8 (4): 329–332. doi:10.1007/BF00173357. ISSN 0179-0358. S2CID 28662055. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Kayaba H, Tamura H, Kitajima S, Fujiwara Y, Kato T, Kato T (November 1996). "Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys". The Journal of Urology. 156 (5): 1813–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65544-7. PMID 8863623.

- Oster J (April 1968). "Further fate of the foreskin. Incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 43 (228): 200–3. doi:10.1136/adc.43.228.200. PMC 2019851. PMID 5689532.

- Edwards S (June 1996). "Balanitis and balanoposthitis: a review". Genitourinary Medicine. 72 (3): 155–9. doi:10.1136/sti.72.3.155. PMC 1195642. PMID 8707315.

- Bolla G, Sartore G, Longo L, Rossi C (2005). "[The sclero-atrophic lichen as principal cause of acquired phimosis in pediatric age]". La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica (in Italian). 27 (3–4): 91–3. PMID 16910457.

- Buechner SA (September 2002). "Common skin disorders of the penis". BJU International. 90 (5): 498–506. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02962.x. PMID 12175386. S2CID 45605100.

- Cantu Jr. S. Phimosis and paraphimosis at eMedicine

- Bromage SJ, Crump A, Pearce I (February 2008). "Phimosis as a presenting feature of diabetes". BJU International. 101 (3): 338–40. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07274.x. PMID 18005214. S2CID 5694950. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- Beaugé M (1997). "The causes of adolescent phimosis". Br J Sex Med. 26 (Sept/Oct).

- Beaugé, Michel (1991). "Conservative Treatment of Primary Phimosis in Adolescents". Faculty of Medicine, Saint-Antoine University.

- Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Kohri K (February 2011). "Prepuce: phimosis, paraphimosis, and circumcision". TheScientificWorldJournal. 11: 289–301. doi:10.1100/tsw.2011.31. PMC 5719994. PMID 21298220.

- Zampieri N, Corroppolo M, Camoglio FS, Giacomello L, Ottolenghi A (November 2005). "Phimosis: stretching methods with or without application of topical steroids?". The Journal of Pediatrics. 147 (5): 705–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.017. PMID 16291369. S2CID 29301071.

- Moreno G, Corbalán J, Peñaloza B, Pantoja T (September 2014). "Topical corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD008973. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008973.pub2. PMID 25180668.

- http://circfacts.org/debunking-corner/#debk5

- Cuckow PM, Rix G, Mouriquand PD (April 1994). "Preputial plasty: a good alternative to circumcision". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 29 (4): 561–3. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(94)90092-2. PMID 8014816.

- Minagawa T, Murata Y (June 2008). "[A case of urinary retention caused by true phimosis]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 54 (6): 427–9. PMID 18634440.

- Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. (September 2005). "Penile cancer: importance of circumcision, human papillomavirus and smoking in in situ and invasive disease". International Journal of Cancer. 116 (4): 606–16. doi:10.1002/ijc.21009. PMID 15825185.

- Shankar KR, Rickwood AM (July 1999). "The incidence of phimosis in boys" (PDF). BJU International. 84 (1): 101–2. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00147.x. PMID 10444134. S2CID 20191682. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28. This study gives a low incidence of pathological phimosis (0.6% of uncircumcised boys by age 15 years) by asserting that balanitis xerotica obliterans is the only indisputable type of pathological phimosis and anything else should be assumed "physiological". Restrictiveness of definition and circularity of reasoning have been criticized.

- Imamura E (August 1997). "Phimosis of infants and young children in Japan". Acta Paediatrica Japonica. 39 (4): 403–5. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200x.1997.tb03605.x. PMID 9316279. S2CID 19407331. A study of phimosis prevalence in over 4,500 Japanese children reporting that over a third of uncircumcised had a nonretractile foreskin by age 3 years.

- Ohjimi T, Ohjimi H (April 1981). "Special surgical techniques for relief of phimosis". The Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 7 (4): 326–30. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00650.x. PMID 7240535.

- "Circumcision and phimosis in eighteenth century France". History of Circumcision. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Hodges FM (1999). "The history of phimosis from antiquity to the present". In Milos MF, Denniston GC, Hodges FM (eds.). Male and Female Circumcision: Medical, Legal and Ethical Considerations in Pediatric Practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 37–62. doi:10.1007/978-0-585-39937-9_5. ISBN 978-0-306-46131-6.

External links

- Phimosis, by the University of California, San Francisco Urology department