Pyramid (geometry)

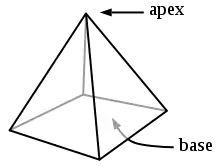

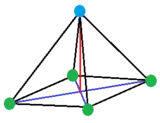

In geometry, a pyramid (from Greek πυραμίς (pyramís)[1][2]) is a polyhedron formed by connecting a polygonal base and a point, called the apex. Each base edge and apex form a triangle, called a lateral face. It is a conic solid with polygonal base. A pyramid with an n-sided base has n + 1 vertices, n + 1 faces, and 2n edges. All pyramids are self-dual.

| Regular-based right pyramids | |

|---|---|

Example: square pyramid | |

| Faces | n triangles 1 n-sided polygon |

| Edges | 2n |

| Vertices | n + 1 |

| Schläfli symbol | ( ) ∨ {n} |

| Conway notation | Yn |

| Symmetry group | Cnv, [1,n], (*nn), order 2n |

| Rotation group | Cn, [1,n]+, (nn), order n |

| Dual polyhedron | self-dual |

| Properties | convex |

A right pyramid has its apex directly above the centroid of its base. Nonright pyramids are called oblique pyramids. A regular pyramid has a regular polygon base and is usually implied to be a right pyramid.[3][4]

When unspecified, a pyramid is usually assumed to be a regular square pyramid, like the physical pyramid structures. A triangle-based pyramid is more often called a tetrahedron.

Among oblique pyramids, like acute and obtuse triangles, a pyramid can be called acute if its apex is above the interior of the base and obtuse if its apex is above the exterior of the base. A right-angled pyramid has its apex above an edge or vertex of the base. In a tetrahedron these qualifiers change based on which face is considered the base.

Pyramids are a class of the prismatoids. Pyramids can be doubled into bipyramids by adding a second offset point on the other side of the base plane.

Right pyramids with a regular base

A right pyramid with a regular base has isosceles triangle sides, with symmetry is Cnv or [1,n], with order 2n. It can be given an extended Schläfli symbol ( ) ∨ {n}, representing a point, ( ), joined (orthogonally offset) to a regular polygon, {n}. A join operation creates a new edge between all pairs of vertices of the two joined figures.[5]

The trigonal or triangular pyramid with all equilateral triangle faces becomes the regular tetrahedron, one of the Platonic solids. A lower symmetry case of the triangular pyramid is C3v, which has an equilateral triangle base, and 3 identical isosceles triangle sides. The square and pentagonal pyramids can also be composed of regular convex polygons, in which case they are Johnson solids.

If all edges of a square pyramid (or any convex polyhedron) are tangent to a sphere so that the average position of the tangential points are at the center of the sphere, then the pyramid is said to be canonical, and it forms half of a regular octahedron.

Pyramids with a hexagon or higher base must be composed of isosceles triangles. A hexagonal pyramid with equilateral triangles would be a completely flat figure, and a heptagonal or higher would have the triangles not meet at all.

| Regular pyramids | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digonal | Triangular | Square | Pentagonal | Hexagonal | Heptagonal | Octagonal | Enneagonal | Decagonal... |

| Improper | Regular | Equilateral | Isosceles | |||||

|

|

|

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Right star pyramids

Right pyramids with regular star polygon bases are called star pyramids.[6] For example, the pentagrammic pyramid has a pentagram base and 5 intersecting triangle sides.

Right pyramids with an irregular base

A right pyramid can be named as ( )∨P, where ( ) is the apex point, ∨ is a join operator, and P is a base polygon.

An isosceles triangle right tetrahedron can be written as ( )∨[( )∨{ }] as the join of a point to an isosceles triangle base, as [( )∨( )]∨{ } or { }∨{ } as the join (orthogonal offsets) of two orthogonal segments, a digonal disphenoid, containing 4 isosceles triangle faces. It has C1v symmetry from two different base-apex orientations, and C2v in its full symmetry.

A rectangular right pyramid, written as ( )∨[{ }×{ }], and a rhombic pyramid, as ( )∨[{ }+{ }], both have symmetry C2v.

|

|

| Rectangular pyramid | Rhombic pyramid |

|---|

Volume

The volume of a pyramid (also any cone) is , where b is the area of the base and h the height from the base to the apex. This works for any polygon, regular or non-regular, and any location of the apex, provided that h is measured as the perpendicular distance from the plane containing the base. In 499 AD Aryabhata, a mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, used this method in the Aryabhatiya (section 2.6).

The formula can be formally proved using calculus. By similarity, the linear dimensions of a cross-section parallel to the base increase linearly from the apex to the base. The scaling factor (proportionality factor) is , or , where h is the height and y is the perpendicular distance from the plane of the base to the cross-section. Since the area of any cross-section is proportional to the square of the shape's scaling factor, the area of a cross-section at height y is , or since both b and h are constants, . The volume is given by the integral

The same equation, , also holds for cones with any base. This can be proven by an argument similar to the one above; see volume of a cone.

For example, the volume of a pyramid whose base is an n-sided regular polygon with side length s and whose height is h is

The formula can also be derived exactly without calculus for pyramids with rectangular bases. Consider a unit cube. Draw lines from the center of the cube to each of the 8 vertices. This partitions the cube into 6 equal square pyramids of base area 1 and height 1/2. Each pyramid clearly has volume of 1/6. From this we deduce that pyramid volume = height × base area / 3.

Next, expand the cube uniformly in three directions by unequal amounts so that the resulting rectangular solid edges are a, b and c, with solid volume abc. Each of the 6 pyramids within are likewise expanded. And each pyramid has the same volume abc/6. Since pairs of pyramids have heights a/2, b/2 and c/2, we see that pyramid volume = height × base area / 3 again.

When the side triangles are equilateral, the formula for the volume is

This formula only applies for n = 2, 3, 4 and 5; and it also covers the case n = 6, for which the volume equals zero (i.e., the pyramid height is zero).

Surface area

The surface area of a pyramid is , where B is the base area, P is the base perimeter, and the slant height , where h is the pyramid altitude and r is the inradius of the base.

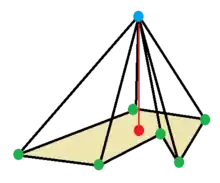

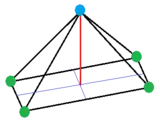

Centroid

The centroid of a pyramid is located on the line segment that connects the apex to the centroid of the base. For a solid pyramid, the centroid is 1/4 the distance from the base to the apex.

n-dimensional pyramids

A 2-dimensional pyramid is a triangle, formed by a base edge connected to a noncolinear point called an apex.

A 4-dimensional pyramid is called a polyhedral pyramid, constructed by a polyhedron in a 3-space hyperplane of 4-space with another point off that hyperplane.

Higher-dimensional pyramids are constructed similarly.

The family of simplices represent pyramids in any dimension, increasing from triangle, tetrahedron, 5-cell, 5-simplex, etc. A n-dimensional simplex has the minimum n+1 vertices, with all pairs of vertices connected by edges, all triples of vertices defining faces, all quadruples of points defining tetrahedral cells, etc.

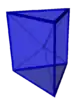

Polyhedral pyramid

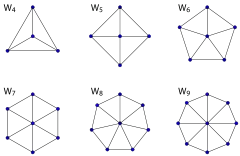

In 4-dimensional geometry, a polyhedral pyramid is a 4-polytope constructed by a base polyhedron cell and an apex point. The lateral facets are pyramid cells, each constructed by one face of the base polyhedron and the apex. The vertices and edges of polyhedral pyramids form examples of apex graphs, graphs formed by adding one vertex (the apex) to a planar graph (the graph of the base).

The regular 5-cell (or 4-simplex) is an example of a tetrahedral pyramid. Uniform polyhedra with circumradii less than 1 can be make polyhedral pyramids with regular tetrahedral sides. A polyhedron with v vertices, e edges, and f faces can be the base on a polyhedral pyramid with v+1 vertices, e+v edges, f+e faces, and 1+f cells.

A 4D polyhedral pyramid with axial symmetry can be visualized in 3D with a Schlegel diagram—a 3D projection that places the apex at the center of the base polyhedron.

| Symmetry | [1,1,4] | [1,2,3] | [1,3,3] | [1,4,3] | [1,5,3] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Square-pyramidal pyramid | Triangular prism pyramid | Tetrahedral pyramid | Cubic pyramid | Octahedral pyramid | Icosahedral pyramid |

| Segmentochora index[7] |

K4.4 | K4.7 | K4.1 | K4.26.1 | K4.3 | K4.84 |

| Height | 0.707107 | 0.645497 | 0.790569 | 0.500000 | 0.707107 | 0.309017 |

| Image (Base) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Base | Square pyramid |

Triangular prism |

Tetrahedron | Cube | Octahedron | Icosahedron |

Any convex 4-polytope can be divided into polyhedral pyramids by adding an interior point and creating one pyramid from each facet to the center point. This can be useful for computing volumes.

The 4-dimensional hypervolume of a polyhedral pyramid is 1/4 of the volume of the base polyhedron times its perpendicular height, compared to the area of a triangle being 1/2 the length of the base times the height and the volume of a pyramid being 1/3 the area of the base times the height.

The 3-dimensional surface volume of a polyhedral pyramid is , where B is the base volume, A is the base surface area, and L is the slant height (height of the lateral pyramidal cells) , where h is the height and r is the inradius.

See also

- Bipyramid

- Cone (geometry)

- Trigonal pyramid (chemistry)

- Frustum

References

- πυραμίς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- The word meant "a kind of cake of roasted wheat-grains preserved in honey"; the Egyptian pyramids were named after its form (R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1261).

- William F. Kern, James R Bland,Solid Mensuration with proofs, 1938, p. 46

- Civil Engineers' Pocket Book: A Reference-book for Engineers Archived 2018-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- N.W. Johnson: Geometries and Transformations, (2018) ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5 Chapter 11: Finite symmetry groups, 11.3 Pyramids, Prisms, and Antiprisms

- Wenninger, Magnus J. (1974), Polyhedron Models, Cambridge University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-521-09859-5, archived from the original on 2013-12-11.

- Convex Segmentochora Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Richard Klitzing, Symmetry: Culture and Science, Vol. 11, Nos. 1–4, 139–181, 2000

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Pyramid". MathWorld.