Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria[note 1] (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Coptic church father[4] and the 20th pope of Alexandria (as Athanasius I). His intermittent episcopacy spanned 45 years (c. 8 June 328 – 2 May 373), of which over 17 encompassed five exiles, when he was replaced on the order of four different Roman emperors. Athanasius was a Christian theologian, a Church Father, the chief defender of Trinitarianism against Arianism, and a noted Egyptian Christian leader of the fourth century.

Athanasius of Alexandria | |

|---|---|

| Pope of Alexandria | |

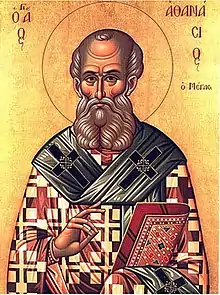

Icon of St Athanasius | |

| Church | Nicene Christianity |

| See | Alexandria |

| Predecessor | Alexander |

| Successor | Peter II |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 296–298[1] Alexandria, Roman Egypt |

| Died | 2 May 373 (aged 75–77) Alexandria, Roman Egypt Philosophy career |

| Occupation | Pope of Alexandria |

| Notable work |

|

| Era | Patristic Age |

| School | |

| Language | Coptic, Greek |

Main interests | Theology |

Notable ideas | Consubstantiality, Trinity, divinity of Jesus, Theotokos[2] |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day |

|

| Venerated in | |

| Title as Saint | Saint and Doctor of the Church |

| Attributes | Bishop arguing with a pagan; bishop holding an open book; bishop standing over a defeated heretic |

| Shrines | Church of San Zaccaria in Venice, Italy |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

|

Conflict with Arius and Arianism, as well as with successive Roman emperors, shaped Athanasius' career. In 325, at age 27, Athanasius began his leading role against the Arians as a deacon and assistant to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria during the First Council of Nicaea. Roman Emperor Constantine the Great had convened the council in May–August 325 to address the Arian position that the Son of God, Jesus of Nazareth, is of a distinct substance from the Father.[5] Three years after that council, Athanasius succeeded his mentor as pope of Alexandria. In addition to the conflict with the Arians (including powerful and influential Arian churchmen led by Eusebius of Nicomedia), he struggled against the Emperors Constantine, Constantius II, Julian the Apostate and Valens. He was known as Athanasius Contra Mundum (Latin for 'Athanasius Against the World').

Nonetheless, within a few years of his death, Gregory of Nazianzus called him the "Pillar of the Church". His writings were well regarded by subsequent Church fathers in the West and the East, who noted their devotion to the Word-become-man, pastoral concern and interest in monasticism. Athanasius is considered one of the four great Eastern Doctors of the Church in the Catholic Church.[6] In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius was the first person to list the 27 books of the New Testament canon that are in use today.[7] He is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church,[8] the Catholic Church,[9] the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Anglican Communion, and Lutheranism.

Biography

Athanasius was born to a Christian family in Alexandria,[10] or possibly the nearby Nile Delta town of Damanhur, sometime between 293 and 298. The earlier date is sometimes assigned because of the maturity revealed in his two earliest treatises Contra Gentes (Against the Heathens) and De Incarnatione (On the Incarnation), which were likely written circa 318 before Arianism had begun to make itself felt, as those writings do not show an awareness of Arianism.[1]

However, Cornelius Clifford places his birth no earlier than 296 and no later than 298, based on the fact that Athanasius indicates no first-hand recollection of the Maximian persecution of 303, which he suggests Athanasius would have remembered if he had been ten years old at the time. Secondly, the Festal Epistles state that the Arians had accused Athanasius, among other charges, of not having yet attained the canonical age (35) and thus could not have been properly ordained as patriarch of Alexandria in 328. The accusation must have seemed plausible.[1] The Orthodox Church places his year of birth around 297.[10]

Education

His parents were wealthy enough to give him a fine secular education.[1] He was, nevertheless, clearly not a member of the Egyptian aristocracy.[11] Some Western scholars consider his command of Greek, in which he wrote most (if not all) of his surviving works, evidence that he may have been a Greek born in Alexandria. Historical evidence, however, indicates that he was fluent in Coptic as well, given the regions of Egypt where he preached.[11] Some surviving copies of his writings are in fact in Coptic, though scholars differ as to whether he wrote them in Coptic originally (which would make him the first patriarch to do so) or whether these were translations of writings originally in Greek.[12][11]

Rufinus relates a story that as Bishop Alexander stood by a window, he watched boys playing on the seashore below, imitating the ritual of Christian baptism. He sent for the children and discovered that one of the boys (Athanasius) had acted as bishop. After questioning Athanasius, Bishop Alexander informed him that the baptisms were genuine, as both the form and matter of the sacrament had been performed through the recitation of the correct words and the administration of water, and that he must not continue to do this as those baptized had not been properly catechized. He invited Athanasius and his playfellows to prepare for clerical careers.[13]

Alexandria was the most important trade centre in the empire during Athanasius's boyhood. Intellectually, morally, and politically—it epitomized the ethnically diverse Graeco-Roman world, even more than Rome or Constantinople, Antioch or Marseilles.[13] Its famous catechetical school, while sacrificing none of its famous passion for orthodoxy since the days of Pantaenus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Dionysius and Theognostus, had begun to take on an almost secular character in the comprehensiveness of its interests and had counted influential pagans among its serious auditors.[14]

Peter of Alexandria, the 17th archbishop of Alexandria, was martyred in 311 in the closing days of the Great Persecution and may have been one of Athanasius's teachers. His successor as bishop of Alexandria was Alexander of Alexandria. According to Sozomen; "the Bishop Alexander 'invited Athanasius to be his commensal and secretary. He had been well educated, and was versed in grammar and rhetoric, and had already, while still a young man, and before reaching the episcopate, given proof to those who dwelt with him of his wisdom and acumen' ".(Soz., II, xvii) [1]

Athanasius' earliest work, Against the Heathen – On the Incarnation (written before 319), bears traces of Origenist Alexandrian thought (such as repeatedly quoting Plato and using a definition from Aristotle's Organon) but in an orthodox way. Athanasius was also familiar with the theories of various philosophical schools and in particular with the developments of neoplatonism. Ultimately, Athanasius would modify the philosophical thought of the School of Alexandria away from the Origenist principles such as the "entirely allegorical interpretation of the text". Still, in later works, Athanasius quotes Homer more than once (Hist. Ar. 68, Orat. iv. 29).

Athanasius knew Greek and admitted not knowing Hebrew [see, e.g., the 39th Festal Letter of St. Athan]. The Old Testament passages he quotes frequently come from the Septuagint Greek translation. Only rarely did he use other Greek versions (to Aquila once in the Ecthesis, to other versions once or twice on the Psalms), and his knowledge of the Old Testament was limited to the Septuagint.[15] The combination of Scriptural study and of Greek learning was characteristic of the famous Alexandrian School.

Bishop (or Patriarch, the highest ecclesial rank in the Centre of the Church, in Alexandria) Alexander ordained Athanasius a deacon in 319.[16] In 325, Athanasius served as Alexander's secretary at the First Council of Nicaea. Already a recognized theologian and ascetic, he was the obvious choice to replace his ageing mentor Alexander as the Patriarch of Alexandria,[17] despite the opposition of the followers of Arius and Meletius of Lycopolis.[16]

At length, in the Council of Nicaea, the term "consubstantial" (homoousion) was adopted, and a formulary of faith embodying it was drawn up by Hosius of Córdoba. From this time to the end of the Arian controversies, the word "consubstantial" continued to be the test of orthodoxy. The formulary of faith drawn up by Hosius is known as the Nicene Creed.[18]: 232 However, "he was not the originator of the famous 'homoousion' (ACC of homoousios). The term had been proposed in a non-obvious and illegitimate sense by Paul of Samosata to the Fathers at Antioch, and had been rejected by them as savouring of materialistic conceptions of the Godhead."[1]

While still a deacon under Alexander's care (or early in his patriarchate as discussed below) Athanasius may have also become acquainted with some of the solitaries of the Egyptian desert, and in particular Anthony the Great, whose life he is said to have written.[13]

Opposition to Arianism

In about 319, when Athanasius was a deacon, a presbyter named Arius came into a direct conflict with Alexander of Alexandria. It appears that Arius reproached Alexander for what he felt were misguided or heretical teachings being taught by the bishop.[19] Arius' theological views appear to have been firmly rooted in Alexandrian Christianity.[20] He embraced a subordinationist Christology which taught that Christ was the divine Son (Logos) of God, made, not begotten. This view was heavily influenced by Alexandrian thinkers like Origen[21] and was a common Christological view in Alexandria at the time.[22] Arius had support from a powerful bishop named Eusebius of Nicomedia (not to be confused with Eusebius of Caesarea),[23] illustrating how Arius's subordinationist Christology was shared by other Christians in the empire. Arius was subsequently excommunicated by Alexander, and Arius began to elicit the support of many bishops who agreed with his position.[16]: 297

Patriarch

| Papal styles of Pope Athanasius I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Pope and Patriarch |

| Posthumous style | Saint |

Frances A. M. Forbes writes that when Patriarch Alexander was on his death-bed he called Athanasius, who fled fearing he would be constrained to be made bishop. "When the Bishops of the Church assembled to elect their new Patriarch, the whole Catholic population surrounded the church, holding up their hands to Heaven and crying; "Give us Athanasius!" The Bishops had nothing better. Athanasius was thus elected, as Gregory tells us..." (Pope Gregory I had full access to the Vatican Archives).[24]: Chapter 4 Alban Butler writes on the subject: "Five months after this great Council, Nicae, St Alexander lying on his deathbed, recommended to his clergy and people the choice of Athanasius for his successor, thrice repeating his name. In consequence of his recommendation, the bishops of all Egypt assembled at Alexandria, and finding the people and clergy unanimous in their choice of Athanasius for patriarch, they confirmed the election about the middle of year 326. He seems, then, to have been about thirty years of age."[25]

T. Gilmartin (Professor of History, Maynooth, 1890) writes: "On the death of Alexander, five months after the termination of the Council of Nicaea, Athanasius was unanimously elected to fill the vacant see. He was most unwilling to accept the dignity, for he clearly foresaw the difficulties in which it would involve him. The clergy and people were determined to have him as their bishop, Patriarch of Alexandria, and refused to accept any excuses. He at length consented to accept a responsibility that he sought in vain to escape, and was consecrated in 326, when he was about thirty years of age."[18]: 244–248

Athanasius' episcopate began on 9 May 328 as the Alexandrian Council elected Athanasius to succeed after the death of Alexander.[18]: 245 Patriarch Athanasius spent over 17 years in five exiles ordered by four different Roman Emperors, not counting approximately six more incidents in which Athanasius fled Alexandria to escape people seeking to take his life.[17] During his first years as bishop, Athanasius visited the churches of his territory, which at that time included all of Egypt and Libya. He established contacts with the hermits and monks of the desert, including Pachomius, which proved very valuable to him over the years.[17]

"During the forty-eight years of his episcopate, his history is told in the history of the controversies in which he was constantly engaged with the Arians, and of the sufferings he had to endure in defence of the Nicene faith. We have seen that when Arius was allowed to return from exile in 328, Athanasius refused to remove the sentence of excommunication."[18]: 245

First exile

Athanasius' first problem lay with Meletius of Lycopolis and his followers, who had failed to abide by the First Council of Nicaea. That council also anathematized Arius. Accused of mistreating Arians and Meletians, Athanasius answered those charges at a gathering of bishops at the First Synod of Tyre in 335. There, Eusebius of Nicomedia and other supporters of Arius deposed Athanasius.[16] On 6 November, both sides of the dispute met with Emperor Constantine I in Constantinople.[26] At that meeting, the Arians claimed Athanasius would try to cut off essential Egyptian grain supplies to Constantinople. He was found guilty and sent into exile to Augusta Treverorum in Gaul (now Trier in Germany).[16][17][27]

When Athanasius reached his destination in exile in 336, Maximin of Trier received him, but not as a disgraced person. Athanasius stayed with him for two years.[25] Constantine died in 337 and was succeeded by his three sons, Constantine II, Constantius, and Constans. Paul I of Constantinople had cautioned Emperor Constans against the Arians, revealing their plots, and he also had been banished and found shelter with Maximin.[28]

Second exile

_-_Athanasios.jpg.webp)

When Emperor Constantine I died, Athanasius was allowed to return to his See of Alexandria. Shortly thereafter, however, Constantius II renewed the order for Athanasius's banishment in 338. "Within a few weeks he set out for Rome to lay his case before the Church at large. He had made his appeal to Pope Julius, who took up his cause with whole-heartedness that never wavered down to the day of that holy pontiff's death. The pope summoned a synod of bishops to meet in Rome. After a careful and detailed examination of the entire case, the primate's innocence was proclaimed to the Christian world."[1] During this time, Gregory of Cappadocia, an Arian bishop, was installed as the patriarch of Alexandria, usurping the absent Athanasius. Athanasius did, however, remain in contact with his people through his annual Festal Letters, in which he also announced on which date Easter would be celebrated that year.[17]

In 339 or 340, nearly one hundred bishops met at Alexandria, declared in favour of Athanasius,[29] and vigorously rejected the criticisms of the Eusebian faction at Tyre. Plus, Pope Julius wrote to the supporters of Arius strongly urging Athanasius's reinstatement, but that effort proved in vain. Julius called a synod in Rome in 340 to address the matter, which proclaimed Athanasius the rightful bishop of Alexandria.[30]

Early in 343 Athanasius met with Hosius of Córdoba, and together they set out for Serdica. A full council of the Church was summoned there in deference to the Roman pontiff's wishes. At this great gathering of prelates, leaders of the Church, the case of Athanasius was taken up once more, that is, Athanasius was formally questioned over misdemeanours and even murder, (a bishop in Egypt named Arsenius had turned up missing, and they blamed his death on Athanasius, even supposedly producing Arsenius' severed hand.)[31]

The council was convoked for the purpose of inquiring into the charges against Athanasius and other bishops, on account of which they were deposed from their sees by the semi-Arian Synod of Antioch in 341 and went into exile. Eusebian bishops objected to the admission of Athanasius and other deposed bishops to the council, except as accused persons to answer the charges brought against them. Their objections were overridden by the orthodox bishops. The Eusebians, seeing they had no chance of having their views carried, retired to Philoppopolis in Thrace where they held an opposition council under the presidency of the Patriarch of Antioch and confirmed the decrees of the Synod of Antioch.[18]: 233–234

Athanasius' innocence was reaffirmed at the Council of Serdica. Two conciliar letters were prepared, one to the clergy and faithful of Alexandria, the other to the bishops of Egypt and Libya, in which the will of the council was made known. Meanwhile, the Eusebians issued an anathema against Athanasius and his supporters. The persecution against the orthodox party broke out with renewed vigour, and Constantius was induced to prepare drastic measures against Athanasius and the priests who were devoted to him. Orders were given that if Athanasius attempted to re-enter his see, he should be put to death. Athanasius, accordingly, withdrew from Serdica to Naissus in Mysia, where he celebrated the Easter festival of the year 344.[1] Hosius presided over the Council of Serdica, as he did for the First Council of Nicaea, which like the 341 synod found Athanasius innocent.[32] He celebrated his last Easter in exile in Aquileia in April 345, received by Bishop Fortunatianus.[33]

The Council of Serdica sent an emissary to report their finding to Constantius. Constantius reconsidered his decision, owing to a threatening letter from his brother Constans and the uncertain conditions of affairs on the Persian border, and he accordingly made up his mind to yield. But three separate letters were needed to overcome the natural hesitation of Athanasius. When he finally acquiesced to meet with Constantius, he was accorded a gracious interview by the emperor and sent back to his see in triumph and began ten years of peace.[1]

Pope Julius died in April 352 and was succeeded by Liberius. For two years Liberius had been favourable to the cause of Athanasius; but driven at last into exile, he was induced to sign an ambiguous formula, from which the great Nicene text, the "homoousion", had been studiously omitted. In 355 a council was held at Milan, where in spite of the vigorous opposition of a handful of loyal prelates among the Western bishops, a fourth condemnation of Athanasius was announced to the world. With his friends scattered, Hosius in exile, and Pope Liberius denounced as acquiescing in Arian formularies, Athanasius could hardly hope to escape. On the night of 8 February 356, while engaged in services in the Church of St. Thomas, a band of armed men burst in to secure his arrest. It was the beginning of his third exile.[1]

Gilmartin writes: "By Constantius' order, the sole ruler of The Roman Empire at the death of his brother Constans, the Council of Arles in 353, was held, which was presided over by Vincent, Bishop of Capua, in the name of Pope Liberius. The fathers terrified of the threats of the Emperor, an avowed Arian, they consented to the condemnation of Athanasius. The Pope refused to accept their decision, and requested the Emperor to hold another Council, in which the charges against Athanasius could be freely investigated. To this Constantius consented, for he felt able to control the Council in Milan."[18]: 234

In 355, three hundred bishops assembled in Milan, most from the West and only a few from the East. They met in the Church of Milan. Shortly, the emperor ordered them to a hall in the Imperial Palace, thus ending any free debate. He presented an Arian formula of faith for their acceptance. He threatened any who refused with exile and death. All, with the exception of Dionysius (bishop of Milan), and the two Papal Legates, viz., Eusebius of Vercelli and Lucifer of Cagliari, consented to the Arian Creed and the condemnation of Athanasius. Those who refused were sent into exile. The decrees were forwarded to the pope for approval but were rejected because of the violence to which the bishops were subjected.[18]: 235

Third exile

Through the influence of the Eusebian faction at Constantinople, an Arian bishop, George of Cappadocia, was appointed to rule the see of Alexandria in 356. Athanasius, after remaining some days in the neighbourhood of the city, finally withdrew into the desert of Upper Egypt where he remained for a period of six years, living the life of the monks and devoting himself to the composition of a group of writings, such as his Letter to the Monks and Four Orations against the Arians.[1] He also defended his own recent conduct in the Apology to Constantius and Apology for His Flight. Constantius' persistence in his opposition to Athanasius, combined with reports Athanasius received about the persecution of non-Arians by the Arian bishop George of Laodicea, prompted Athanasius to write his more emotional History of the Arians, in which he described Constantius as a precursor of the Antichrist.[17]

Constantius died on 4 November 361 and was succeeded by Julian. The proclamation of the new prince's accession was the signal for a pagan outbreak against the still dominant Arian faction in Alexandria. George, the usurping bishop, was imprisoned and murdered. An obscure presbyter named Pistus was chosen by the Arians to succeed him, when news arrived that filled the orthodox party with hope. An edict had been put forth by Julian permitting the exiled bishops of the "Galileans" to return to their "towns and provinces". Athanasius accordingly returned to Alexandria on 22 February 362.[1]

In 362 Athanasius convened a council at Alexandria and presided over it with Eusebius of Vercelli. Athanasius appealed for unity among all those who had faith in Christianity, even if they differed on matters of terminology. This prepared the groundwork for his definition of the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. However, the council also was directed against those who denied the divinity of the Holy Spirit, the human soul of Christ, and Christ's divinity. Mild measures were agreed on for those heretic bishops who repented, but severe penance was decreed for the chief leaders of the major heresies.[34]

With characteristic energy he set to work to re-establish the somewhat shattered fortunes of the orthodox party and to purge the theological atmosphere of uncertainty. To clear up the misunderstandings that had arisen in the course of the previous years, an attempt was made to determine still further the significance of the Nicene formularies. In the meanwhile, Julian, who seems to have become suddenly jealous of the influence that Athanasius was exercising at Alexandria, addressed an order to Ecdicius, the Prefect of Egypt, peremptorily commanding the expulsion of the restored primate on the ground that he had not been included in the imperial act of clemency. The edict was communicated to the bishop by Pythicodorus Trico, who, though described in the "Chronicon Athanasianum" (XXXV) as a "philosopher", seems to have behaved with brutal insolence. On 23 October the people gathered about the proscribed bishop to protest against the emperor's decree; but Athanasius urged them to submit, consoling them with the promise that his absence would be of short duration.[1]

Fourth exile

In 362 Julian, noted for his opposition to Christianity, ordered Athanasius to leave Alexandria once again. Athanasius left for Upper Egypt, remaining there with the Desert Fathers until Julian's death on 26 June 363. Athanasius returned in secret to Alexandria, where he received a document from the new emperor, Jovian, reinstating him once more in his episcopal functions.[1] His first act was to convene a council which reaffirmed the terms of the Nicene Creed. Early in September 363 he set out for Antioch on the Orontes, bearing a synodal letter, in which the pronouncements of this council had been embodied. At Antioch he had an interview with Jovian, who received him graciously and even asked him to prepare an exposition of the orthodox faith. In February 364 Jovian died.[1]

Fifth exile

The accession of Emperor Valens gave a fresh lease of life to the Arian party. He issued a decree banishing the bishops who had been deposed by Constantius but who had been permitted by Jovian to return to their sees. The news created the greatest consternation in Alexandria, and the prefect, in order to prevent a serious outbreak, gave public assurance that the very special case of Athanasius would be laid before the emperor. But Athanasius seems to have divined what was preparing in secret against him. He quietly withdrew from Alexandria in October 364 and took up his abode in a country house outside the city. Valens, who seems to have sincerely dreaded the possible consequences of another popular outbreak, within a few weeks issued orders allowing Athanasius to return to his episcopal see.[1][17] Some early reports state that Athanasius spent this period of exile at his family's ancestral tomb[16] in a Christian cemetery.

Final years and death

After returning to Alexandria, Athanasius spent his final years repairing all the damage done during the earlier years of violence, dissent, and exile. He resumed writing and preaching undisturbed, and characteristically re-emphasized the view of the Incarnation which had been defined at Nicaea. On 2 May 373, having consecrated Peter II, one of his presbyters as his successor, Athanasius died peacefully in his own bed, surrounded by his clergy and faithful supporters.[13]

Works

In Coptic literature, Athanasius is the first patriarch of Alexandria to use Coptic as well as Greek in his writings.[12]

Polemical and theological works

Athanasius was not a speculative theologian. As he states in his First Letters to Serapion, he held on to "the tradition, teaching, and faith proclaimed by the apostles and guarded by the fathers."[16] He held that both the Son of God and the Holy Spirit are consubstantial with the Father, which had a great deal of influence in the development of later doctrines regarding the Trinity.[16] Athanasius' "Letter Concerning the Decrees of the Council of Nicaea" (De Decretis), is an important historical as well as theological account of the proceedings of that council.

Examples of Athanasius' polemical writings against his theological opponents include Orations Against the Arians, his defence of the divinity of the Holy Spirit (Letters to Serapion in the 360s, and On the Holy Spirit), against Macedonianism and On the Incarnation.[17] Athanasius also authored a two-part work, Against the Heathen and The Incarnation of the Word of God. Completed probably early in his life, before the Arian controversy,[35] they constitute the first classic work of developed Orthodox theology. In the first part, Athanasius attacks several pagan practices and beliefs. The second part presents teachings on the redemption.[16] Also in these books, Athanasius put forward the belief, referencing John 1:1–4, that the Son of God, the eternal Word (Logos) through whom God created the world, entered that world in human form to lead men back into the harmony from which they had earlier fallen away.[36]

His other important works include his Letters to Serapion, which defends the divinity of the Holy Spirit. In a letter to Epictetus of Corinth, Athanasius anticipates future controversies in his defence of the humanity of Christ. In a letter addressed to the monk Dracontius, Anathasius urges him to leave the desert for the more active duties of a bishop.[17] Athanasius also wrote several works of Biblical exegesis, primarily on Old Testament materials. The most important of these is his Epistle to Marcellinus (PG 27:12–45) on how to incorporate psalm-saying into one's spiritual practice. Excerpts remain of his discussions concerning the Book of Genesis, the Song of Solomon, and Psalms.

Perhaps his most notable letter was his Festal Letter, written to his Church in Alexandria when he was in exile, as he could not be in their presence. This letter clearly shows his stand that accepting Jesus as the Divine Son of God is not optional but necessary:

I know moreover that not only this thing saddens you, but also the fact that while others have obtained the churches by violence, you are meanwhile cast out from your places. For they hold the places, but you the Apostolic Faith. They are, it is true, in the places, but outside of the true Faith; while you are outside the places indeed, but the Faith, within you. Let us consider whether is the greater, the place or the Faith. Clearly the true Faith. Who then has lost more, or who possesses more? He who holds the place, or he who holds the Faith?[37]

Biographical and ascetic works

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

His biography of Anthony the Great entitled Life of Antony[38](Βίος καὶ Πολιτεία Πατρὸς Ἀντωνίου, Vita Antonii) became his most widely read work. Translated into several languages, it became something of a best seller in its day and played an important role in the spreading of the ascetic ideal in Eastern and Western Christianity.[17] It depicts Anthony as an illiterate yet holy man who continuously engages in spiritual exercises in the Egyptian desert and struggles against demonic powers. It later served as an inspiration to Christian monastics in both the East and the West.[39] Athanasius' works on asceticism also include a Discourse on Virginity, a short work on Love and Self-Control, and a treatise On Sickness and Health (of which only fragments remain).

Misattributed works

There are several other works ascribed to him, although not necessarily generally accepted as being his own. These include the so-called Athanasian Creed (which is today generally seen as being of 5th-century Galician origin), and a complete Expositions on the Psalms.[16]

Eschatology

Based on his understanding of the prophecies of Daniel and the Book of Revelation, Athanasius described Jesus’ Second Coming in the clouds of heaven and pleads with his readers to be ready for that day, at which time Jesus would judge the earth, raise the dead, cast out the wicked, and establish his kingdom. Athanasius also argued that the date of Jesus’ earthly sojourn was divinely foretold beyond refutation by the seventy weeks prophecy of Daniel 9.[40]

Veneration

Athanasius was originally buried in Alexandria, but his remains were later transferred to the Chiesa di San Zaccaria in Venice, Italy. During Pope Shenouda III's visit to Rome (4–10 May 1973), Pope Paul VI gave the Coptic Patriarch a relic of Athanasius,[41] which he brought back to Egypt on 15 May.[42] The relic is currently preserved under the new Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo. However, the majority of Athanasius's corpse remains in the Venetian church.[43]

All major Christian denominations which officially recognize saints venerate Athanasius. Western Christians observe his feast day on 2 May, the anniversary of his death. The Catholic Church considers Athanasius a Doctor of the Church.[6] For Coptic Christians, his feast day is Pashons 7 (now circa 15 May). Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendars remember Athanasius on 18 January.[44] Athanasius is honored on the liturgical calendars of the Church of England and the Episcopal Church on 2 May.[45][46] Gregory of Nazianzus (330–390, also a Doctor of the Church), said: "When I praise Athanasius, virtue itself is my theme: for I name every virtue as often as I mention him who was possessed of all virtues. He was the true pillar of the Church. His life and conduct were the rule of bishops, and his doctrine the rule of the orthodox faith."[13]

Tomb of Saint Zaccaria and Saint Athanasius in Venice

Tomb of Saint Zaccaria and Saint Athanasius in Venice

Procession of a statue at Bellante

Procession of a statue at Bellante

Character

Historian Cornelius Clifford says in his account: "Athanasius was the greatest champion of Catholic belief on the subject of the Incarnation that the Church has ever known and in his lifetime earned the characteristic title of 'Father of Orthodoxy', by which he has been distinguished ever since."[1] Clifford also says: "His career almost personifies a crisis in the history of Christianity; and he may be said rather to have shaped the events in which he took part than to have been shaped by them."[1] St. John Henry Newman describes him as a "principal instrument, after the Apostles, by which the sacred truths of Christianity have been conveyed and secured to the world".[47]

The greater majority of Church leaders and the emperors fell into support for Arianism, so much so that Jerome (340–420) wrote of the period: "The whole world groaned and was amazed to find itself Arian".[18] He, Athanasius, even suffered an unjust excommunication from Pope Liberius who was exiled and leant towards compromise, until he was allowed back to the See of Rome. Athanasius stood virtually alone against the world.[25]

Historical significance and controversies

New Testament canon

It was the custom of the bishops of Alexandria to circulate a letter after Epiphany each year confirming the date of Easter and therefore other moveable feasts. They also took the occasion to discuss other matters. Athanasius wrote forty-five festal letters.[48] Athanasius' 39th Festal Letter, written in 367, is widely regarded as a milestone in the evolution of the canon of New Testament books.[49] Athanasius is the first person to identify the same 27 books of the New Testament that are in use today. Up until then, various similar lists of works to be read in churches were in use. Athanasius compiled the list to resolve questions about such texts as the Epistle of Barnabas. Athanasius includes the Book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah and places the Book of Esther among the "7 books not in the canon but to be read" along with the Wisdom of Solomon, Book of Sirach, Book of Judith, Book of Tobit, the Didache, and The Shepherd of Hermas.[50]

Athanasius' list is similar to the Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican Library, probably written in Rome in 340 by Alexandrian scribes for Emperor Constans, during the period of Athanasius' seven-year exile in the city. The establishment of the canon was not a unilateral decision by a bishop in Alexandria but the result of a process of careful investigation and deliberation, as documented in a codex of the Greek Bible and, twenty-seven years later, in his festal letter.[48] Pope Damasus I, the bishop of Rome in 382, promulgated a list of books which contained a New Testament canon identical to that of Athanasius. A synod in Hippo in 393 repeated Athanasius' and Damasus' New Testament list (without the Epistle to the Hebrews), and the Council of Carthage (397) repeated Athanasius' and Damasus' complete New Testament list.[51]

Scholars debate whether Athanasius' list in 367 formed the basis for later lists. Because Athanasius' canon is the closest canon of any of the Church Fathers to the one used by Protestant churches today, many Protestants point to Athanasius as the Father of the Canon.[50][52]

Supporters

Christian denominations worldwide revere Athanasius as a saint and teacher. They cite his defence of the Christology described in the first chapter of the Gospel of St. John[1:1–4] and his significant theological works (C. S. Lewis calls On the Incarnation of the Word of God a "masterpiece")[53] as evidence of his righteousness. They also emphasize his close relationship with Anthony the Great, the ancient monk who was one of the founders of the Christian monastic movement.

The Gospel of St. John, and particularly the first chapter, demonstrates the Divinity of Jesus. This Gospel is the greatest support of Athanasius' stand. The Gospel of St. John's first chapter began to be said at the end of Mass, we believe as a result of Athanasius and his life's stand.[1:1–14] The beginning of John's Gospel was much used as an object of special devotion throughout the Middle Ages; the practice of saying it at the altar grew, and eventually Pope Pius V made this practice universal for the Roman Rite in his 1570 edition of the Missal.[54] It became a firm custom with exceptions in using another Gospel in use from 1920.[55][56] Cyril of Alexandria (370–444) in the first letter says: "Athanasius is one who can be trusted: he would not say anything that is not in accord with sacred scripture." (Ep 1).

Critics

Throughout most of his career, Athanasius had many detractors. Classics scholar Timothy Barnes recounts ancient allegations against Athanasius: from defiling an altar, to selling Church grain that had been meant to feed the poor for his own personal gain, and even violence and murder to suppress dissent.[57] Athanasius used "Arian" to describe both followers of Arius and as a derogatory polemical term for Christians who disagreed with his formulation of the Trinity.[58] Athanasius called many of his opponents "Arian", except for Meletius.[59]

Scholars now believe that the Arian party was not monolithic[60] but held drastically different theological views that spanned the early Christian theological spectrum.[61][62][63] They supported the tenets of Origenist thought and subordinationist theology[64] but had little else in common. Moreover, many labelled "Arian" did not consider themselves followers of Arius.[65] In addition, non-homoousian bishops disagreed with being labeled as followers of Arius, since Arius was merely a presbyter, while they were fully ordained bishops.[66]

The old allegations continue to be made against Athanasius, however, many centuries later. For example, Richard E. Rubenstein suggests that Athanasius ascended to the rank of bishop in Alexandria under questionable circumstances because some questioned whether he had reached the minimum age of 30 years, and further that Athanasius employed force when it suited his cause or personal interests. Thus, he argues that a small number of bishops who supported Athanasius held a private consecration to make him bishop.[67]

Selected works

- Athanasius. Contra Gentes – De Incarnatione (translated by Thompson, Robert W.), text and ET (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971).

- On the Incarnation at theologynetwork.org

- Letters to Serapion (on the Holy Spirit) at archive.org

See also

- Arabic Homily of Pseudo-Theophilus of Alexandria

- Eastern Catholic Church

- Eugenius of Carthage

- Homoousian

- Pontifical Greek College of Saint Athanasius

- Saint Athanasius of Alexandria, patron saint archive

Explanatory notes

Citations

-

Clifford, Cornelius (1907). "St. Athanasius". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Clifford, Cornelius (1907). "St. Athanasius". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - "The rejection of the term Theotokos by Nestorius Constantinople and the refutation of his teaching by Cyril of Alexandria". Egolpion.com. 24 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- "St. Takla Haymanout Coptic Orthodox Website".

- Laos, Nicolas (2016). Methexiology: Philosophical Theology and Theological Philosophy for the Deification of Humanity. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-4982-3385-9.

- "First Council of Nicaea". Encyclopædia Britannica.

-

Chapman, John (1909). "Doctors of the Church". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Chapman, John (1909). "Doctors of the Church". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Livingstone, E. A.; Sparkes, M. W. D.; Peacocke, R. W., eds. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-19965962-3. OCLC 1023248322.

- "Online Chapel – Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". www.goarch.org.

- Online, Catholic. "St. Athanasius – Saints & Angels". Catholic Online.

- "St. Athanasius the Great the Patriarch of Alexandria". oca.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Barnes, Timothy David (2001). Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 13.

- "Coptic literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Clifford, Cornelius, Catholic Encyclopedia 1930, Volume 2, pp. 35–40 "Athanasius".

- Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., VI, xix

- Ἀλεξανδρεὺς τῷ γένει, ἀνὴρ λόγιος, δυνατὸς ὢν ἐν ταῖς γραφαῖς

- Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 2 Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier Incorporated, 1997. ISBN 0-7172-0129-5.

- Hardy, Edward R. "Saint Athanasius". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- T. Gilmartin, Manual of Church History, Vol. 1. Ch XVII, 1890.

- Kannengiesser, Charles, "Alexander and Arius of Alexandria: The last Ante-Nicene theologians", Miscelanea En Homenaje Al P. Antonio Orbe Compostellanum Vol. XXXV, no. 1–2. (Santiago de Compostela, 1990), 398

- Williams, Rowan, Arius: Heresy and Tradition (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1987), 175

- Williams, 175

- Williams 154–155

- Alexander of Alexandria's Catholic Epistle

- Forbes, F. A. (1919). Saint Athanasius: The Father of Orthodoxy. Standard-bearers of the Faith: A Series of Lives of the Saints for Young and Old. London: R. & T. Washbourne, Ltd.

- Butler, Alban (1894). Lives of the Saints. Benziger Bros., Inc. pp. 164–165.

- Barnes, Timothy D., Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 23

- Christianity, Daily Telegraph 1999

-

Ott, Michael (1911). "St. Maximinus". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Ott, Michael (1911). "St. Maximinus". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Clark, William R. (2007). A History of the Councils of the Church: from the Original Documents, to the close of the Second Council of Nicaea A.D. 787. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 9781556352478.

- Davis, Leo Donald (1983). The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787): Their History and Theology. Liturgical Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780814656167.

- Milman, Henry Hart (1881). The History of Christianity, from the Birth of Christ to the Abolition of Paganism in the Roman Empire. T. Y. Crowell. p. 382.

- "St. Athanasius – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Barnes, Timothy David, Athanasius and Constantius, Harvard 2001, p. 66

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Justo L. Gonzalez in A History of Christian Thought notes (p. 292) that E. Schwartz places this work later, around 335, but "his arguments have not been generally accepted". The introduction to the CSMV translation of On the Incarnation places the work in 318, around the time Athanasius was ordained to the diaconate (St Athanasius On the Incarnation, Mowbray, England 1953)

- "Church Fathers: On the Incarnation of the Word (Athanasius)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- "fragment conjectured to belong to a festal letter".

- "Athanasius of Alexandria: Vita S. Antoni [Life of St. Antony] (written bwtween 356 and 362)". Fordham University. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Athanasius". Christian History. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Froom 1950, p. 393.

- "Metropolitan Bishoy of Damiette". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- "Saint Athanasius". Avarewase.org. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- "The Incorrupt Relics of Saint Athanasios the Great". Johnsanidopoulos.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- January 18/January 31. Orthodox Calendar (Pravoslavie.ru).

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-234-7.

- "Letter of St. Athanasius". Society of Saint Pius X. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- "367 Athanasius Defines the New Testament". Christian History. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Gwynn, David M. (16 February 2012). Athanasius of Alexandria: Bishop, Theologian, Ascetic, Father. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-921095-4 – via Google Books.

- Bediako, Gillian Mary; Quarshie, Bernhardt; Asamoah-Gyadu, J. Kwabena (14 January 2015). Seeing New Facets of the Diamond: Christianity as a Universal Faith - Essays in Honor of Kwame Bediako. Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781498217293 – via Google Books.

- Von Dehsen, Christian. "St. Athanasius", Philosophers and Religious Leaders, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 9781135951023

- "Excerpt from Letter 39". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- Introduction to St. Athanasius on the Incarnation. Translated and edited by Sister Penelope Lawson, published by Mowbray 1944. p. 9

- Fortescue, Adrian, Catholic Encyclopedia 1907, Volume 6, pp. 662–663 "Gospel"

- Pope Benedict XV, Missale Romanum, IX Additions & Variations of the Rubrics of The Missal

- See also: Jungmann, El Sacrificio de la Misa, No. 659, 660

- Barnes, Timothy D., Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 37

- Barnes, Timothy D., Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 14, 128

- Barnes "Athanasius and Constantius", 135

- Haas, Christopher, "The Arians of Alexandria", Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 47, no. 3 (1993), 239

- Chadwick, Henry, "Faith and Order at the Council of Nicaea", Harvard Theological Review LIII (Cambridge Mass: 1960), 173

- Williams, 63

- Kannengiesser "Alexander and Arius", 403

- Kannengiesser, "Athanasius of Alexandria vs. Arius: The Alexandrian Crisis", in The Roots of Egyptian Christianity (Studies in Antiquity and Christianity), ed. Birger A. Pearson and James E. Goehring (1986), 208

- Williams, 82

- Rubinstein, Richard, When Jesus Became God, The Struggle to Define Christianity during the Last Days of Rome, 1999

- Rubenstein, Richard E., When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight over Christ's Divinity in the Last Days of Rome (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1999), 105–106

General and cited sources

- Alexander of Alexandria, "Catholic Epistle", The Ecole Initiative, ecole.evansville.edu

- Anatolios, Khaled, Athanasius: The Coherence of His Thought (New York: Routledge, 1998).

- Arnold, Duane W.-H., The Early Episcopal Career of Athanasius of Alexandria (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame, 1991).

- Arius, "Arius's letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia", Ecclesiastical History, ed. Theodoret. Ser. 2, Vol. 3, 41, The Ecole Initiative, ecole.evansville.edu

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. (New York: Penguin, 1993). ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- Barnes, Timothy D., Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Barnes, Timothy D., Constantine and Eusebius (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981)

- Bouter, P.F. (2010). Athanasius (in Dutch). Kampen: Kok.

- Brakke, David. Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism (1995)

- Clifford, Cornelius, "Athanasius", Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2 (1907), 35–40

- Chadwick, Henry, "Faith and Order at the Council of Nicaea", Harvard Theological Review LIII (Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1960), 171–195.

- Ernest, James D., The Bible in Athanasius of Alexandria (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

- Froom, Le Roy Edwin (1950). The prophetic faith of our fathers : the historical development of prophetic interpretation (PDF). Vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald. ISBN 9780828024563.

- Freeman, Charles, The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (Alfred A. Knopf, 2003).

- Haas, Christopher. "The Arians of Alexandria", Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 47, no. 3 (1993), 234–245.

- Hanson, R.P.C., The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318–381 (T.&T. Clark, 1988).

- Kannengiesser, Charles, "Alexander and Arius of Alexandria: The last Ante-Nicene theologians", Miscelanea En Homenaje Al P. Antonio Orbe Compostellanum Vol. XXXV, no. 1–2. (Santiago de Compostela, 1990), 391–403.

- Kannengiesser, Charles "Athanasius of Alexandria vs. Arius: The Alexandrian Crisis", in The Roots of Egyptian Christianity (Studies in Antiquity and Christianity), ed. Birger A. Pearson and James E. Goehring (1986), 204–215.

- Ng, Nathan K. K., The Spirituality of Athanasius (1991).

- Pettersen, Alvyn (1995). Athanasius. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Morehouse.

- Rubenstein, Richard E., When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight over Christ's Divinity in the Last Days of Rome (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1999).

- Williams, Rowan, Arius: Heresy and Tradition (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1987).

Further reading

- Anatolios, Khaled. Athanasius (London: Routledge, 2004). [Contains selections from the Orations against the Arians (pp. 87–175) and Letters to Serapion on the Holy Spirit (pp. 212–233), together with the full texts of On the Council of Nicaea (pp. 176–211) and Letter 40: To Adelphius (pp. 234–242)]

- Gregg, Robert C. Athanasius: The Life of Antony and the Letter to Marcellinus, Classics of Western Spirituality (New York: Paulist Press, 1980).

- Schaff, Philip (1867). History of the Christian Church: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, AD 311–600. Vol. 3rd. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson.

- Schaff, Philip; Henry Wace (1903). A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church: St. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters. Vol. 4th. New York: Scribner.

External links

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἀθανάσιος Ἀλεξανδρείας

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἀθανάσιος Ἀλεξανδρείας- Official web site of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa

- Works by Patriarch of Alexandria Saint Athanasius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Athanasius of Alexandria at Internet Archive

- Works by Athanasius of Alexandria at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Archibald Robinson, Athanasius: Select Letters and Works (Edinburgh 1885)

- The so-called Athanasian Creed (not written by Athanasius, see Athanasian Creed above)

- Athanasius Select Resources, Bilingual Anthology (in Greek original and English)

- Two audio lectures about Athanasius on the Deity of Christ, Dr N Needham

- Concorida Cyclopedia: Athanasius

- Christian Cyclopedia: Athanasius

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- St Athanasius the Great the Archbishop of Alexandria Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- English Key to Athanasius Werke

- The Writings of Athanasius in Chronological Order

- Introducing...Athanasius audio resource by Dr. Michael Reeves. Two lectures on theologynetwork.org

- Letter of Saint Athanasius to His Flock at the Our Lady of the Rosary Library

- St. Athanasius Patriarch of Alexandria at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- Colonnade Statue in St Peter's Square

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%252C_4-July-2008.jpg.webp)