Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia

Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia included indigenous Arabian polytheism, ancient Semitic religions, Christianity, Judaism, Mandaeism, and Iranian religions such as Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeism.

| Part of a series on |

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Islam and other religions |

|---|

|

| Abrahamic religions |

|

| Other religions |

|

| Islam and... |

|

|

Arabian polytheism, the dominant form of religion in pre-Islamic Arabia, was based on veneration of deities and spirits. Worship was directed to various gods and goddesses, including Hubal and the goddesses al-Lāt, al-‘Uzzā, and Manāt, at local shrines and temples such as the Kaaba in Mecca. Deities were venerated and invoked through a variety of rituals, including pilgrimages and divination, as well as ritual sacrifice. Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion. Many of the physical descriptions of the pre-Islamic gods are traced to idols, especially near the Kaaba, which is said to have contained up to 360 of them.

Other religions were represented to varying, lesser degrees. The influence of the adjacent Roman and Aksumite civilizations resulted in Christian communities in the northwest, northeast, and south of Arabia. Christianity made a lesser impact in the remainder of the peninsula, but did secure some conversions. With the exception of Nestorianism in the northeast and the Persian Gulf, the dominant form of Christianity was Miaphysitism. The peninsula had been a destination for Jewish migration since Roman times, which had resulted in a diaspora community supplemented by local converts. Additionally, the influence of the Sasanian Empire resulted in Iranian religions being present in the peninsula. Zoroastrianism existed in the east and south, while there is evidence of Manichaeism or possibly Mazdakism being practiced in Mecca.

Background and sources

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Until about the fourth century, almost all inhabitants of Arabia practiced polytheistic religions.[1] Although significant Jewish and Christian minorities developed, polytheism remained the dominant belief system in pre-Islamic Arabia.[2][3]

The contemporary sources of information regarding the pre-Islamic Arabian religion and pantheon include a small number of inscriptions and carvings,[3] pre-Islamic poetry, external sources such as Jewish and Greek accounts, as well as the Muslim tradition, such as the Qur'an and Islamic writings. Nevertheless, information is limited.[3]

One early attestation of Arabian polytheism was in Esarhaddon’s Annals, mentioning Atarsamain, Nukhay, Ruldaiu, and Atarquruma.[4] Herodotus, writing in his Histories, reported that the Arabs worshipped Orotalt (identified with Dionysus) and Alilat (identified with Aphrodite).[5][6] Strabo stated the Arabs worshipped Dionysus and Zeus. Origen stated they worshipped Dionysus and Urania.[6]

Muslim sources regarding Arabian polytheism include the eighth-century Book of Idols by Hisham ibn al-Kalbi, which F.E. Peters argued to be the most substantial treatment of the religious practices of pre-Islamic Arabia,[7] as well as the writings of the Yemeni historian al-Hasan al-Hamdani on South Arabian religious beliefs.[8]

According to the Book of Idols, descendants of the son of Abraham (Ishmael) who had settled in Mecca migrated to other lands. They carried holy stones from the Kaaba with them, erected them, and circumambulated them like the Kaaba.[9] This, according to al-Kalbi led to the rise of idol worship.[9] Based on this, it may be probable that Arabs originally venerated stones, later adopting idol-worship under foreign influences.[9] The relationship between a god and a stone as his representation can be seen from the third-century Syriac work called the Homily of Pseudo-Meliton where he describes the pagan faiths of Syriac-speakers in northern Mesopotamia, who were mostly Arabs.[9]

Worship

Deities

The pre-Islamic Arabian religions were polytheistic, with many of the deities' names known.[1] Formal pantheons are more noticeable at the level of kingdoms, of variable sizes, ranging from simple city-states to collections of tribes.[10] Tribes, towns, clans, lineages and families had their own cults too.[10] Christian Julien Robin suggests that this structure of the divine world reflected the society of the time.[10] Trade caravans also brought foreign religious and cultural influences.[11]

A large number of deities did not have proper names and were referred to by titles indicating a quality, a family relationship, or a locale preceded by "he who" or "she who" (dhū or dhāt respectively).[10]

The religious beliefs and practices of the nomadic Bedouin were distinct from those of the settled tribes of towns such as Mecca.[12] Nomadic religious belief systems and practices are believed to have included fetishism, totemism and veneration of the dead but were connected principally with immediate concerns and problems and did not consider larger philosophical questions such as the afterlife.[12] Settled urban Arabs, on the other hand, are thought to have believed in a more complex pantheon of deities.[12] While the Meccans and the other settled inhabitants of the Hejaz worshiped their gods at permanent shrines in towns and oases, the Bedouin practiced their religion on the move.[13]

Minor spirits

In South Arabia, mndh’t were anonymous guardian spirits of the community and the ancestor spirits of the family.[14] They were known as ‘the sun (shms) of their ancestors’.[14]

In North Arabia, ginnaye were known from Palmyrene inscriptions as "the good and rewarding gods" and were probably related to the jinn of west and central Arabia.[15] Unlike jinn, ginnaye could not hurt nor possess humans and were much more similar to the Roman genius.[16] According to common Arabian belief, soothsayers, pre-Islamic philosophers, and poets were inspired by the jinn.[17] However, jinn were also feared and thought to be responsible for causing various diseases and mental illnesses.[18]

Malevolent beings

Aside from benevolent gods and spirits, there existed malevolent beings.[15] These beings were not attested in the epigraphic record, but were alluded to in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, and their legends were collected by later Muslim authors.[15]

Commonly mentioned are ghouls.[15] Etymologically, the English word "ghoul" was derived from the Arabic ghul, from ghala, "to seize",[19] related to the Sumerian galla.[20] They are said to have a hideous appearance, with feet like those of an ass.[15] Arabs were said to utter the following couplet if they should encounter one: "Oh ass-footed one, just bray away, we won't leave the desert plain nor ever go astray."[15]

Christian Julien Robin notes that all the known South Arabian divinities had a positive or protective role and that evil powers were only alluded to but were never personified.[21]

Roles of deities

| Part of the myth series on |

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Pre-Islamic Arabian deities |

| Arabian deities of other Semitic origins |

|

Role of Allah

Some scholars postulate that in pre-Islamic Arabia, including in Mecca,[22] Allah was considered to be a deity,[22] possibly a creator deity or a supreme deity in a polytheistic pantheon.[23][24] The word Allah (from the Arabic al-ilah meaning "the god")[25] may have been used as a title rather than a name.[26][27][28] The concept of Allah may have been vague in the Meccan religion.[29] According to Islamic sources, Meccans and their neighbors believed that the goddesses Al-lāt, Al-‘Uzzá, and Manāt were the daughters of Allah.[2][24][26][27][30]

Regional variants of the word Allah occur in both pagan and Christian pre-Islamic inscriptions.[31][32] References to Allah are found in the poetry of the pre-Islamic Arab poet Zuhayr bin Abi Sulma, who lived a generation before Muhammad, as well as pre-Islamic personal names.[33] Muhammad's father's name was ʿAbd-Allāh, meaning "the servant of Allah".[29]

Charles Russell Coulter and Patricia Turner considered that Allah's name may be derived from a pre-Islamic god called Ailiah and is similar to El, Il, Ilah, and Jehovah. They also considered some of his characteristics to be seemingly based on lunar deities like Almaqah, Kahl, Shaker, Wadd and Warakh.[34] Alfred Guillaume states that the connection between Ilah that came to form Allah and ancient Babylonian Il or El of ancient Israel is not clear. Wellhausen states that Allah was known from Jewish and Christian sources and was known to pagan Arabs as the supreme god.[35] Winfried Corduan doubts the theory of Allah of Islam being linked to a moon god, stating that the term Allah functions as a generic term, like the term El-Elyon used as a title for the god Sin.[36]

South Arabian inscriptions from the fourth century AD refer to a god called Rahman ("The Merciful One") who had a monotheistic cult and was referred to as the "Lord of heaven and Earth".[24] Aaron W. Hughes states that scholars are unsure whether he developed from the earlier polytheistic systems or developed due to the increasing significance of the Christian and Jewish communities, and that it is difficult to establish whether Allah was linked to Rahmanan.[24] Maxime Rodinson, however, considers one of Allah's names, "Ar-Rahman", to have been used in the form of Rahmanan earlier.[37]

Al-Lat, al-Uzza and Manat

Al-Lāt, Al-‘Uzzá and Manāt were common names used for multiple goddesses across Arabia.[26][38][39][40][41] G. R. Hawting states that modern scholars have frequently associated the names of Arabian goddesses Al-lāt, Al-‘Uzzá and Manāt with cults devoted to celestial bodies, particularly Venus, drawing upon evidence external to the Muslim tradition as well as in relation to Syria, Mesopotamia and the Sinai Peninsula.[42]

Allāt (Arabic: اللات) or al-Lāt was worshipped throughout the ancient Near East with various associations.[34] Herodotus in the 5th century BC identifies Alilat (Greek: Ἀλιλάτ) as the Arabic name for Aphrodite (and, in another passage, for Urania),[5] which is strong evidence for worship of Allāt in Arabia at that early date.[43] Al-‘Uzzá (Arabic: العزى) was a fertility goddess[44] or possibly a goddess of love.[45] Manāt (Arabic: مناة) was the goddess of destiny.[46]

Al-Lāt's cult was spread in Syria and northern Arabia. From Safaitic and Hismaic inscriptions, it is probable that she was worshiped as Lat (lt). F. V. Winnet saw al-Lat as a lunar deity due to the association of a crescent with her in 'Ayn esh-Shallāleh and a Lihyanite inscription mentioning the name of Wadd, the Minaean moon god, over the title of fkl lt. René Dussaud and Gonzague Ryckmans linked her with Venus while others have thought her to be a solar deity. John F. Healey considers that al-Uzza actually might have been an epithet of al-Lāt before becoming a separate deity in the Meccan pantheon.[47] Paola Corrente, writing in Redefining Dionysus, considers she might have been a god of vegetation or a celestial deity of atmospheric phenomena and a sky deity.[48]

Mythology

According to F. E. Peters, "one of the characteristics of Arab paganism as it has come down to us is the absence of a mythology, narratives that might serve to explain the origin or history of the gods."[49] Many of the deities have epithets, but are lacking myths or narratives to decode the epithets, making them generally uninformative.[50]

Practices

Cult images and idols

The worship of sacred stones constituted one of the most important practices of the Semitic peoples, including Arabs.[51] Cult images of a deity were most often an unworked stone block.[52] The most common name for these stone blocks was derived from the Semitic nsb ("to be stood upright"), but other names were used, such as Nabataean masgida ("place of prostration") and Arabic duwar ("object of circumambulation", this term often occurs in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry).[53] These god-stones were usually a free-standing slab, but Nabataean god-stones are usually carved directly on the rock face.[53] Facial features may be incised on the stone (especially in Nabataea), or astral symbols (especially in South Arabia).[53] Under Greco-Roman influence, an anthropomorphic statue might be used instead.[52]

The Book of Idols describes two types of statues: idols (sanam) and images (wathan).[54] If a statue were made of wood, gold, or silver, after a human form, it would be an idol, but if the statue were made of stone, it would be an image.[54]

Representation of deities in animal-form was common in South Arabia, such as the god Sayin from Hadhramaut, who was represented as either an eagle fighting a serpent or a bull.[55]

Sacred places

Sacred places are known as hima, haram or mahram, and within these places, all living things were considered inviolable and violence was forbidden.[56] In most of Arabia, these places would take the form of open-air sanctuaries, with distinguishing natural features such as springs and forests.[56] Cities would contain temples, enclosing the sacred area with walls, and featuring ornate structures.[57]

Priesthood and sacred offices

Sacred areas often had a guardian or a performer of cultic rites.[58] These officials were thought to tend the area, receive offerings, and perform divination.[58] They are known by many names, probably based on cultural-linguistic preference: afkal was used in the Hejaz, kâhin was used in the Sinai-Negev-Hisma region, and kumrâ was used in Aramaic-influenced areas.[58] In South Arabia, rs2w and 'fkl were used to refer to priests, and other words include qyn ("administrator") and mrtd ("consecrated to a particular divinity").[59] A more specialized staff is thought to have existed in major sanctuaries.[58]

Pilgrimages

Pilgrimages to sacred places would be made at certain times of the year.[60] Pilgrim fairs of central and northern Arabia took place in specific months designated as violence-free,[60] allowing several activities to flourish, such as trade, though in some places only exchange was permitted.[61]

South Arabian pilgrimages

The most important pilgrimage in Saba' was probably the pilgrimage of Almaqah at Ma'rib, performed in the month of dhu-Abhi (roughly in July).[59] Two references attest the pilgrimage of Almaqah dhu-Hirran at 'Amran.[59] The pilgrimage of Ta'lab Riyam took place in Mount Tur'at and the Zabyan temple at Hadaqan, while the pilgrimage of Dhu-Samawi, the god of the Amir tribe, took place in Yathill.[59] Aside from Sabaean pilgrimages, the pilgrimage of Sayin took place at Shabwa.[59][60]

Meccan pilgrimage

The pilgrimage of Mecca involved the stations of Mount Arafat, Muzdalifah, Mina and central Mecca that included Safa and Marwa as well as the Kaaba. Pilgrims at the first two stations performed wuquf or standing in adoration. At Mina, animals were sacrificed. The procession from Arafat to Muzdalifah, and from Mina to Mecca, in a pre-reserved route towards idols or an idol, was termed ijaza and ifada, with the latter taking place before sunset. At Jabal Quzah, fires were started during the sacred month.[62]

Nearby the Kaaba was located the betyl which was later called Maqam Ibrahim; a place called al-Ḥigr which Aziz al-Azmeh takes to be reserved for consecrated animals, basing his argument on a Sabaean inscription mentioning a place called mḥgr which was reserved for animals; and the Well of Zamzam. Both Safa and Marwa were adjacent to two sacrificial hills, one called Muṭ'im al Ṭayr and another Mujāwir al-Riḥ which was a pathway to Abu Kubais from where the Black Stone is reported to have originated.[63]

Cult associations

Meccan pilgrimages differed according to the rites of different cult associations, in which individuals and groups joined for religious purposes. The Ḥilla association performed the hajj in autumn season while the Ṭuls and Ḥums performed the umrah in spring.[64]

The Ḥums were the Quraysh, Banu Kinanah, Banu Khuza'a and Banu 'Amir. They did not perform the pilgrimage outside the zone of Mecca's haram, thus excluding Mount Arafat. They also developed certain dietary and cultural restrictions.[65] According to Kitab al-Muhabbar, the Ḥilla denoted most of the Banu Tamim, Qays, Rabi`ah, Qūḍa'ah, Ansar, Khath'am, Bajīlah, Banu Bakr ibn Abd Manat, Hudhayl, Asad, Tayy and Bariq. The Ṭuls comprised the tribes of Yemen and Hadramaut, 'Akk, Ujayb and Īyād. The Basl recognised at least eight months of the calendar as holy. There was also another group which didn't recognize the sanctity of Mecca's haram or holy months, unlike the other four.[66]

Astrology and divination

The ancient Arabs that inhabitated the Arabian Peninsula before the advent of Islam used to profess a widespread belief in fatalism (ḳadar) alongside a fearful consideration for the sky and the stars, which they held to be ultimately responsible for every phenomena that occurs on Earth and for the destiny of humankind.[67] Accordingly, they shaped their entire lives in accordance with their interpretations of astral configurations and phenomena.[67]

In South Arabia, oracles were regarded as ms’l, or "a place of asking", and that deities interacted by hr’yhw ("making them see") a vision, a dream, or even direct interaction.[68] Otherwise deities interacted indirectly through a medium.[69]

There were three methods of chance-based divination attested in pre-Islamic Arabia; two of these methods, making marks in the sand or on rocks and throwing pebbles are poorly attested.[70] The other method, the practice of randomly selecting an arrow with instructions, was widely attested and was common throughout Arabia.[70] A simple form of this practice was reportedly performed before the image of Dhu'l-Khalasa by a certain man, sometimes said to be the Kindite poet Imru al-Qays according to al-Kalbi.[71][72] A more elaborate form of the ritual was performed in before the image of Hubal.[73] This form of divination was also attested in Palmyra, evidenced by an honorific inscription in the temple of al-Lat.[73]

Offerings and ritual sacrifice

The most common offerings were animals, crops, food, liquids, inscribed metal plaques or stone tablets, aromatics, edifices and manufactured objects.[75] Camel-herding Arabs would devote some of their beasts to certain deities. The beasts would have their ears slit and would be left to pasture without a herdsman, allowing them to die a natural death.[75]

Pre-Islamic Arabians, especially pastoralist tribes, sacrificed animals as an offering to a deity.[74] This type of offering was common and involved domestic animals such as camels, sheep and cattle, while game animals and poultry were rarely or never mentioned. Sacrifice rites were not tied to a particular location though they were usually practiced in sacred places.[74] Sacrifice rites could be performed by the devotee, though according to Hoyland, women were probably not allowed.[76] The victim's blood, according to pre-Islamic Arabic poetry and certain South Arabian inscriptions, was also 'poured out' on the altar stone, thus forming a bond between the human and the deity.[76] According to Muslim sources, most sacrifices were concluded with communal feasts.[76]

In South Arabia, beginning with the Christian era, or perhaps a short while before, statuettes were presented before the deity, known as slm (male) or slmt (female).[59]

Human sacrifice was sometimes carried out in Arabia. The victims were generally prisoners of war, who represented the god's part of the victory in booty, although other forms might have existed.[74]

Blood sacrifice was definitely practiced in South Arabia, but few allusions to the practice are known, apart from some Minaean inscriptions.[59]

Other practices

In the Hejaz, menstruating women were not allowed to be near the cult images.[55] The area where Isaf and Na'ila's images stood was considered out-of-bounds for menstruating women.[55] This was reportedly the same with Manaf.[77] According to the Book of Idols, this rule applied to all the "idols".[55] This was also the case in South Arabia, as attested in a South Arabian inscription from al-Jawf.[55]

Sexual intercourse in temples was prohibited, as attested in two South Arabian inscriptions.[55] One legend concerning Isaf and Na'ila, when two lovers made love in the Kaaba and were petrified, joining the idols in the Kaaba, echoes this prohibition.[55]

By geography

Eastern Arabia

The Dilmun civilization, which existed along the Persian Gulf coast and Bahrain until the 6th century BC, worshipped a pair of deities, Inzak and Meskilak.[78] It is not known whether these were the only deities in the pantheon or whether there were others.[79] The discovery of wells at the sites of a Dilmun temple and a shrine suggests that sweet water played an important part in religious practices.[78]

In the subsequent Greco-Roman period, there is evidence that the worship of non-indigenous deities was brought to the region by merchants and visitors.[79] These included Bel, a god popular in the Syrian city of Palmyra, the Mesopotamian deities Nabu and Shamash, the Greek deities Poseidon and Artemis and the west Arabian deities Kahl and Manat.[79]

South Arabia

The main sources of religious information in pre-Islamic South Arabia are inscriptions, which number in the thousands, as well as the Quran, complemented by archaeological evidence.

The civilizations of South Arabia are considered to have the most developed pantheon in the Arabian peninsula.[50] In South Arabia, the most common god was 'Athtar, who was considered remote. The patron deity (shym) was considered to be of much more immediate significance than 'Athtar. Thus, the kingdom of Saba' had Almaqah, the kingdom of Ma'in had Wadd, the kingdom of Qataban had 'Amm, and the kingdom of Hadhramaut had Sayin. Each people was termed the "children" of their respective patron deity. Patron deities played a vital role in sociopolitical terms, their cults serving as the focus of a person's cohesion and loyalty.

Evidence from surviving inscriptions suggests that each of the southern kingdoms had its own pantheon of three to five deities, the major deity always being a god.[80] For example, the pantheon of Saba comprised Almaqah, the major deity, together with 'Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan.[80] The main god in Ma'in and Himyar was 'Athtar, in Qataban it was Amm, and in Hadhramaut it was Sayin.[80] 'Amm was a lunar deity and was associated with the weather, especially lightning.[81] One of the most frequent titles of the god Almaqah was "Lord of Awwam".[82]

Anbay was an oracular god of Qataban and also the spokesman of Amm.[83] His name was invoked in royal regulations regarding water supply.[84] Anbay's name was related to that of the Babylonian deity Nabu. Hawkam was invoked alongside Anbay as god of "command and decision" and his name is derived from the root word "to be wise".[4]

Each kingdom's central temple was the focus of worship for the main god and would be the destination for an annual pilgrimage, with regional temples dedicated to a local manifestation of the main god.[80] Other beings worshipped included local deities or deities dedicated to specific functions as well as deified ancestors.[80]

Influence of Arab tribes

The encroachment of northern Arab tribes into South Arabia also introduced northern Arab deities into the region.[21] The three goddesses al-Lat, al-Uzza and Manat became known as Lat/Latan, Uzzayan and Manawt.[21] Uzzayan's cult in particular was widespread in South Arabia, and in Qataban she was invoked as a guardian of the final royal palace.[21] Lat/Latan was not significant in South Arabia, but appears to be popular with the Arab tribes bordering Yemen.[21] Other Arab deities include Dhu-Samawi, a god originally worshipped by the Amir tribe, and Kahilan, perhaps related to Kahl of Qaryat al-Faw.[21]

Bordering Yemen, the Azd Sârat tribe of the Asir region was said to have worshipped Dhu'l-Shara, Dhu'l-Kaffayn, Dhu'l-Khalasa and A'im.[85] According to the Book of Idols, Dhu'l-Kaffayn originated from a clan of the Banu Daws.[86] In addition to being worshipped among the Azd, Dushara is also reported to have a shrine amongst the Daws.[86] Dhu’l-Khalasa was an oracular god and was also worshipped by the Bajila and Khatham tribes.[72]

Influence on Aksum

Before conversion to Christianity, the Aksumites followed a polytheistic religion that was similar to that of Southern Arabia. The lunar god Hawbas was worshiped in South Arabia and Aksum.[87] The name of the god Astar, a sky-deity was related to that of 'Attar.[88] The god Almaqah was worshiped at Hawulti-Melazo.[89] The South Arabian gods in Aksum included Dhat-Himyam and Dhat-Ba'adan.[90] A stone later reused for the church of Enda-Cerqos at Melazo mentions these gods. Hawbas is also mentioned on an altar and sphinx in Dibdib. The name of Nrw who is mentioned in Aksum inscriptions is related to that of the South Arabian god Nawraw, a deity of stars.[91]

Transition to Judaism

The Himyarite kings radically opposed polytheism in favor of Judaism, beginning officially in 380.[92] The last trace of polytheism in South Arabia, an inscription commemorating a construction project with a polytheistic invocation, and another, mentioning the temple of Ta’lab, all date from just after 380 (the former dating to the rule of the king Dhara’amar Ayman, and the latter dating to the year 401–402).[92] The rejection of polytheism from the public sphere did not mean the extinction of it altogether, as polytheism likely continued in the private sphere.[92]

Central Arabia

The Kinda tribe's chief god was Kahl, whom their capital Qaryat Dhat Kahl (modern Qaryat al-Faw) was named for.[93][94] His name appears in the form of many inscriptions and rock engravings on the slopes of the Tuwayq, on the walls of the souk of the village, in the residential houses and on the incense burners.[94] An inscription in Qaryat Dhat Kahl invokes the gods Kahl, Athtar al-Shariq and Lah.[95]

Hejaz

According to Islamic sources, the Hejaz region was home to three important shrines dedicated to al-Lat, al-’Uzza and Manat. The shrine and idol of al-Lat, according to the Book of Idols, once stood in Ta'if, and was primarily worshipped by the Banu Thaqif tribe.[96] Al-’Uzza's principal shrine was in Nakhla and was the chief-goddess of the Quraysh tribe.[97][98] Manāt's idol, reportedly the oldest of the three, was erected on the seashore between Medina and Mecca, and was honored by the Aws and Khazraj tribes.[99] Inhabitants of several areas venerated Manāt, performing sacrifices before her idol, and pilgrimages of some were not considered completed until they visited Manāt and shaved their heads.[54]

In the Muzdalifah region near Mecca, the god Quzah, who is a god of rains and storms, was worshipped. In pre-Islamic times pilgrims used to halt at the "hill of Quzah" before sunrise.[100] Qusai ibn Kilab is traditionally reported to have introduced the association of fire worship with him on Muzdalifah.[100]

Various other deities were venerated in the area by specific tribes, such as the god Suwa' by the Banu Hudhayl tribe and the god Nuhm by the Muzaynah tribe.[101]

Historiography

The majority of extant information about Mecca during the rise of Islam and earlier times comes from the text of the Quran itself and later Muslim sources such as the prophetic biography literature dealing with the life of Muhammad and the Book of Idols.[102] Alternative sources are so fragmentary and specialized that writing a convincing history of this period based on them alone is impossible.[103] Several scholars hold that the sīra literature is not independent of the Quran but has been fabricated to explain the verses of the Quran.[104] There is evidence to support the contention that some reports of the sīras are of dubious validity, but there is also evidence to support the contention that the sīra narratives originated independently of the Quran.[104] Compounding the problem is that the earliest extant Muslim historical works, including the sīras, were composed in their definitive form more than a century after the beginning of the Islamic era.[105] Some of these works were based on subsequently lost earlier texts, which in their turn recorded a fluid oral tradition.[103] Scholars do not agree as to the time when such oral accounts began to be systematically collected and written down,[106] and they differ greatly in their assessment of the historical reliability of the available texts.[104][107][108]

Role of Mecca and the Kaaba

The Kaaba, whose environs were regarded as sacred (haram), became a national shrine under the custodianship of the Quraysh, the chief tribe of Mecca, which made the Hejaz the most important religious area in north Arabia.[109] Its role was solidified by a confrontation with the Christian king Abraha, who controlled much of Arabia from a seat of power in Yemen in the middle of the sixth century.[110] Abraha had recently constructed a splendid church in Sana'a, and he wanted to make that city a major center of pilgrimage, but Mecca's Kaaba presented a challenge to his plan.[110] Abraha found a pretext for an attack on Mecca, presented by different sources alternatively as pollution of the church by a tribe allied to the Meccans or as an attack on Abraha's grandson in Najran by a Meccan party.[110] The defeat of the army he assembled to conquer Mecca is recounted with miraculous details by the Islamic tradition and is also alluded to in the Quran and pre-Islamic poetry.[110] After the battle, which probably occurred around 565, the Quraysh became a dominant force in western Arabia, receiving the title "God's people" (ahl Allah) according to Islamic sources, and formed the cult association of ḥums, which tied members of many tribes in western Arabia to the Kaaba.[110]

The Kaaba, Allah, and Hubal

According to tradition, the Kaaba was a cube-like, originally roofless structure housing a black stone revered as a relic.[111] The sanctuary was dedicated to Hubal (Arabic: هبل), who, according to some sources, was worshiped as the greatest of the 360 idols the Kaaba contained, which probably represented the days of the year.[112] Ibn Ishaq and Ibn Al-Kalbi both report that the human-shaped idol of Hubal made of precious stone came into the possession of the Quraysh with its right hand broken off and that the Quraysh made a hand of gold to replace it.[113] A soothsayer performed divination in the shrine by drawing ritual arrows,[109] and vows and sacrifices were made to assure success.[114] Marshall Hodgson argues that relations with deities and fetishes in pre-Islamic Mecca were maintained chiefly on the basis of bargaining, where favors were expected in return for offerings.[114] A deity's or oracle's failure to provide the desired response was sometimes met with anger.[114]

Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion. According to one hypothesis, which goes back to Julius Wellhausen, Allah (the supreme deity of the tribal federation around Quraysh) was a designation that consecrated the superiority of Hubal (the supreme deity of Quraysh) over the other gods.[31] However, there is also evidence that Allah and Hubal were two distinct deities.[31] According to that hypothesis, the Kaaba was first consecrated to a supreme deity named Allah and then hosted the pantheon of Quraysh after their conquest of Mecca, about a century before the time of Muhammad.[31] Some inscriptions seem to indicate the use of Allah as a name of a polytheist deity centuries earlier, but we know nothing precise about this use.[31] Some scholars have suggested that Allah may have represented a remote creator god who was gradually eclipsed by more particularized local deities.[28] There is disagreement on whether Allah played a major role in the Meccan religious cult.[2][25] No iconic representation or idol of Allah is known to have existed.[25][115]

Other deities

The three chief goddesses of Meccan religion were al-Lat, Al-‘Uzzá, and Manāt, who were called the daughters of Allah.[2][26][27][30] Egerton Sykes meanwhile states that Al-lāt was the female counterpart of Allah while Uzza was a name given by Banu Ghatafan to the planet Venus.[116]

Other deities of the Quraysh in Mecca included Manaf, Isaf and Na’ila. Although the early Arab historian Al-Tabari calls Manaf (Arabic: مناف) "one of the greatest deities of Mecca", very little information is available about it. Women touched his idol as a token of blessing, and kept away from it during menstruation. Gonzague Ryckmans described this as a practice peculiar to Manaf, but according to the Encyclopedia of Islam, a report from Ibn Al-Kalbi indicates that it was common to all idols.[117] Muhammad's great-great-grandfather's name was Abd Manaf which means "slave of Manaf".[118] He is thought by some scholars to be a sun-god.[119] The idols of Isāf and Nā'ila were located near the Black Stone with a talbiyah performed to Isāf during sacrifices. Various legends existed about the idols, including one that they were petrified after they committed adultery in the Kaaba.[63]

The pantheon of the Quraysh was not identical with that of the tribes who entered into various cult and commercial associations with them, especially that of the hums.[120][121] Christian Julien Robin argues that the former was composed principally of idols that were in the sanctuary of Mecca, including Hubal and Manaf, while the pantheon of the associations was superimposed on it, and its principal deities included the three goddesses, who had neither idols nor a shrine in that city.[120]

Political and religious developments

The second half of the sixth century was a period of political disorder in Arabia and communication routes were no longer secure.[122] Religious divisions were an important cause of the crisis.[123] Judaism became the dominant religion in Yemen while Christianity took root in the Persian Gulf area.[123] In line with the broader trends of the ancient world, Arabia yearned for a more spiritual form of religion and began believing in afterlife, while the choice of religion increasingly became a personal rather than communal choice.[123] While many were reluctant to convert to a foreign faith, those faiths provided intellectual and spiritual reference points, and the old pagan vocabulary of Arabic began to be replaced by Jewish and Christian loanwords from Aramaic everywhere, including Mecca.[123] The distribution of pagan temples supports Gerald Hawting's argument that Arabian polytheism was marginalized in the region and already dying in Mecca on the eve of Islam.[123] The practice of polytheistic cults was increasingly limited to the steppe and the desert, and in Yathrib (later known as Medina), which included two tribes with polytheistic majorities, the absence of a public pagan temple in the town or its immediate neighborhood indicates that polytheism was confined to the private sphere.[123] Looking at the text of the Quran itself, Hawting has also argued that the criticism of idolaters and polytheists contained in Quran is in fact a hyperbolic reference to other monotheists, in particular the Arab Jews and Arab Christians, whose religious beliefs were considered imperfect.[104][124] According to some traditions, the Kaaba contained no statues, but its interior was decorated with images of Mary and Jesus, prophets, angels, and trees.[31]

To counter the effects of anarchy, the institution of sacred months, during which every act of violence was prohibited, was reestablished.[125] During those months, it was possible to participate in pilgrimages and fairs without danger.[125] The Quraysh upheld the principle of two annual truces, one of one month and the second of three months, which conferred a sacred character to the Meccan sanctuary.[125] The cult association of hums, in which individuals and groups partook in the same rites, was primarily religious, but it also had important economic consequences.[125] Although, as Patricia Crone has shown, Mecca could not compare with the great centers of caravan trade on the eve of Islam, it was probably one of the most prosperous and secure cities of the peninsula, since, unlike many of them, it did not have surrounding walls.[125] Pilgrimage to Mecca was a popular custom.[126] Some Islamic rituals, including processions around the Kaaba and between the hills of al-Safa and Marwa, as well as the salutation "we are here, O Allah, we are here" repeated on approaching the Kaaba are believed to have antedated Islam.[126] Spring water acquired a sacred character in Arabia early on and Islamic sources state that the well of Zamzam became holy long before the Islamic era.[127]

Advent of Islam

According to Ibn Sa'd, the opposition in Mecca started when the prophet of Islam, Muhammad, delivered verses that "spoke shamefully of the idols they (the Meccans) worshiped other than Himself (God) and mentioned the perdition of their fathers who died in disbelief".[128] According to William Montgomery Watt, as the ranks of Muhammad's followers swelled, he became a threat to the local tribes and the rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life, which Muhammad threatened to overthrow.[129] Muhammad's denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, the Quraysh, as they were the guardians of the Kaaba.[129]

The conquest of Mecca around 629–630 AD led to the destruction of the idols around the Kaaba, including Hubal.[130] Following the conquest, shrines and temples dedicated to deities were destroyed, such as the shrines to al-Lat, al-’Uzza and Manat in Ta’if, Nakhla and al-Qudayd respectively.[131][132]

North Arabia

Less complex societies outside South Arabia often had smaller pantheons, with the patron deity having much prominence. The deities attested in north Arabian inscriptions include Ruda, Nuha, Allah, Dathan, and Kahl.[133] Inscriptions in a North Arabian dialect in the region of Najd referring to Nuha describe emotions as a gift from him. In addition, they also refer to Ruda being responsible for all things good and bad.[133]

The Safaitic tribes in particular prominently worshipped the goddess al-Lat as a bringer of prosperity.[133] The Syrian god Baalshamin was also worshipped by Safaitic tribes and is mentioned in Safaitic inscriptions.[134]

Religious worship amongst the Qedarites, an ancient tribal confederation that was probably subsumed into Nabataea around the 2nd century AD, was centered around a polytheistic system in which women rose to prominence. Divine images of the gods and goddesses worshipped by Qedarite Arabs, as noted in Assyrian inscriptions, included representations of Atarsamain, Nuha, Ruda, Dai, Abirillu and Atarquruma. The female guardian of these idols, usually the reigning queen, served as a priestess (apkallatu, in Assyrian texts) who communed with the other world.[135] There is also evidence that the Qedar worshipped al-Lat to whom the inscription on a silver bowl from a king of Qedar is dedicated.[40] In the Babylonian Talmud, which was passed down orally for centuries before being transcribed c. 500 AD, in tractate Taanis (folio 5b), it is said that most Qedarites worshiped pagan gods.[136]

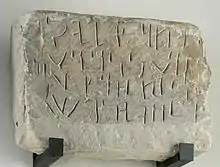

The Aramaic stele inscription discovered by Charles Hubert in 1880 at Tayma mentions the introduction of a new god called Salm of hgm into the city's pantheon being permitted by three local gods – Salm of Mahram who was the chief god, Shingala, and Ashira. The name Salm means "image" or "idol".[137]

The Midianites, a people referred to in the Book of Genesis and located in north-western Arabia, may have worshipped Yahweh.[138] Indeed, some scholars believe that Yahweh was originally a Midianite god and that he was subsequently adopted by the Israelites.[138] An Egyptian temple of Hathor continued to be used during the Midianite occupation of the site, although images of Hathor were defaced suggesting Midianite opposition.[138] They transformed it into a desert tent-shrine set up with a copper sculpture of a snake.[138]

The Lihyanites worshipped the god Dhu-Ghabat and rarely turned to others for their needs.[84] Dhu-Ghabat's name means "he of the thicket", based on the etymology of gabah, meaning forest or thicket.[139] The god al-Kutba', a god of writing probably related to a Babylonian deity and perhaps was brought into the region by the Babylonian king Nabonidus,[84] is mentioned in Lihyanite inscriptions as well.[140] The worship of the Hermonian gods Leucothea and Theandrios was spread from Phoenicia to Arabia.[141]

According to the Book of Idols, the Tayy tribe worshipped al-Fals, whose idol stood on Jabal Aja,[142] while the Kalb tribe worshipped Wadd, who had an idol in Dumat al-Jandal.[143][144]

Nabataeans

The Nabataeans worshipped primarily northern Arabian deities. Under foreign influences, they also incorporated foreign deities and elements into their beliefs.

The Nabataeans’ chief-god is Dushara. In Petra, the only major goddess is Al-‘Uzzá, assuming the traits of Isis, Tyche and Aphrodite. It is unknown if her worship and identity is related to her cult at Nakhla and others. The Nabatean inscriptions define Allāt and Al-Uzza as the "bride of Dushara". Al-Uzza may have been an epithet of Allāt in the Nabataean religion according to John F. Healey.[145]

Outside Petra, other deities were worshipped; for example, Hubal and Manat were invoked in the Hejaz, and al-Lat was invoked in the Hauran and the Syrian desert. The Nabataean king Obodas I, who founded Obodat, was deified and worshipped as a god.[146] They also worshipped Shay al-Qawm,[147] al-Kutba',[140] and various Greco-Roman deities such as Nike and Tyche.[148] Maxime Rodinson suggests that Hubal, who was popular in Mecca, had a Nabataean origin.[149]

_Archaeological_Museum_Amman_Citadel_Jordan0820.jpg.webp)

The worship of Pakidas, a Nabataean god, is attested at Gerasa alongside Hera in an inscription dated to the first century A.D. while an Arabian god is also attested by three inscriptions dated to the second century.[150]

The Nabataeans were known for their elaborate tombs, but they were not just for show; they were meant to be comfortable places for the dead.[151] Petra has many "sacred high places" which include altars that have usually been interpreted as places of human sacrifice, although, since the 1960s, an alternative theory that they are "exposure platforms" for placing the corpses of the deceased as part of a funerary ritual has been put forward. However, there is, in fact, little evidence for either proposition.[152]

Religious beliefs of Arabs outside Arabia

Palmyra was a cosmopolitan society, with its population being a mix of Aramaeans and Arabs. The Arabs of Palmyra worshipped al-Lat, Rahim and Shamash. The temple of al-Lat was established by the Bene Ma'zin tribe, who were probably an Arab tribe.[153] The nomads of the countryside worshipped a set of deities, bearing Arab names and attributes,[154] most prominent of them was Abgal,[155] who himself is not attested in Palmyra itself.[156] Ma'n, an Arab god, was worshipped alongside Abgal in a temple dedicated in 195 AD at Khirbet Semrin in the Palmyrene region while an inscription dated 194 AD at Ras esh-Shaar calls him the "good and bountiful god". A stele at Ras esh-Shaar shows him riding a horse with a lance while the god Saad is riding a camel. Abgal, Ma'n and Sa'd were known as the genii.[157]

The god Ashar was represented on a stele in Dura-Europos alongside another god Sa'd. The former was represented on a horse with Arab dress while the other was shown standing on the ground. Both had Parthian hairstyle, large facial hair and moustaches as well as similar clothing. Ashar's name is found to have been used in a theophoric manner among the Arab-majority areas of the region of the Northwest Semitic languages, like Hatra, where names like "Refuge of Ashar", "Servant of Ashar" and "Ashar has given" are recorded on an inscription.[158]

In Edessa, the solar deity was the primary god around the time of the Roman Emperor Julian and this worship was presumably brought in by migrants from Arabia. Julian's oration delivered to the denizens of the city mentioned that they worshipped the Sun surrounded by Azizos and Monimos whom Iamblichus identified with Ares and Hermes respectively. Monimos derived from Mu'nim or "the favourable one", and was another name of Ruda or Ruldaiu as apparent from spellings of his name in Sennacherib's Annals.[159]

The idol of the god al-Uqaysir was, according to the Book of Idols, located in Syria, and was worshipped by the tribes of Quda'a, Lakhm, Judham, Amela, and Ghatafan.[160] Adherents would go on a pilgrimage to the idol and shave their heads, then mix their hair with wheat, "for every single hair a handful of wheat".[160]

A shrine to Dushara has been discovered in the harbour of ancient Puteoli in Italy. The city was an important nexus for trade to the Near East, and it is known to have had a Nabataean presence during the mid 1st century BCE.[161] A Minaean altar dedicated to Wadd evidently existed in Delos, containing two inscriptions in Minaean and Greek respectively.[162]

Bedouin religious beliefs

The Bedouin were introduced to Meccan ritualistic practices as they frequented settled towns of the Hejaz during the four months of the "holy truce", the first three of which were devoted to religious observance, while the fourth was set aside for trade.[109] Alan Jones infers from Bedouin poetry that the gods, even Allah, were less important to the Bedouins than Fate.[163] They seem to have had little trust in rituals and pilgrimages as means of propitiating Fate, but had recourse to divination and soothsayers (kahins).[163] The Bedouins regarded some trees, wells, caves and stones as sacred objects, either as fetishes or as means of reaching a deity.[164] They created sanctuaries where people could worship fetishes.[165]

The Bedouins had a code of honor which Fazlur Rahman Malik states may be regarded as their religious ethics. This code encompassed women, bravery, hospitality, honouring one's promises and pacts, and vengeance. They believed that the ghost of a slain person would cry out from the grave until their thirst for blood was quenched. Practices such as killing of infant girls were often regarded as having religious sanction.[165] Numerous mentions of jinn in the Quran and testimony of both pre-Islamic and Islamic literature indicate that the belief in spirits was prominent in pre-Islamic Bedouin religion.[166] However, there is evidence that the word jinn is derived from Aramaic, ginnaye, which was widely attested in Palmyrene inscriptions. The Aramaic word was used by Christians to designate pagan gods reduced to the status of demons, and was introduced into Arabic folklore only late in the pre-Islamic era.[166] Julius Wellhausen has observed that such spirits were thought to inhabit desolate, dingy and dark places and that they were feared.[166] One had to protect oneself from them, but they were not the objects of a true cult.[166]

Bedouin religious experience also included an apparently indigenous cult of ancestors.[166] The dead were not regarded as powerful, but rather as deprived of protection and needing charity of the living as a continuation of social obligations beyond the grave.[166] Only certain ancestors, especially heroes from which the tribe was said to derive its name, seem to have been objects of real veneration.[166]

Other religions

Iranian religions

Iranian religions existed in pre-Islamic Arabia on account of Sasanian military presence along the Persian Gulf and South Arabia and on account of trade routes between the Hejaz and Iraq. Some Arabs in northeast of the peninsula converted to Zoroastrianism and several Zoroastrian temples were constructed in Najd. Some of the members from the tribe of Banu Tamim had converted to the religion. There is also evidence of existence of Manichaeism in Arabia as several early sources indicate a presence of "zandaqas" in Mecca, although the term could also be interpreted as referring to Mazdakism. However, according to the most recent research by Tardieu, the prevalence of Manichaeism in Mecca during the 6th and 7th centuries, when Islam emerged, can not be proven.[167][168][169] Similar reservations regarding the appearance of Manichaeism and Mazdakism in pre-Islamic Mecca are offered by Trompf & Mikkelsen et al. in their latest work (2018).[170][171] There is evidence for the circulation of Iranian religious ideas in the form of Persian loan words in Quran such as firdaws (paradise).[172][173]

Zoroastrianism was also present in Eastern Arabia[174][175][176] and Persian-speaking Zoroastrians lived in the region.[177] The religion was introduced in the region including modern-day Bahrain during the rule of Persian empires in the region starting from 250 B.C. It was mainly practiced in Bahrain by Persian settlers. Zoroastrianism was also practiced in the Persian-ruled area of modern-day Oman. The religion also existed in Persian-ruled area of modern Yemen. The descendants of Abna, the Persian conquerors of Yemen, were followers of Zoroastrianism.[178][179] Yemen's Zoroastrians who had the jizya imposed on them after being conquered by Muhammad are mentioned by the Islamic historian al-Baladhuri.[179] According to Serjeant, the Baharna people may be the Arabized descendants of converts from the original population of ancient Persians (majus) as well as other religions.[180]

Judaism

A thriving community of Jewish tribes existed in pre-Islamic Arabia and included both sedentary and nomadic communities. Jews had migrated into Arabia from Roman times onwards.[181] Arabian Jews spoke Arabic as well as Hebrew and Aramaic and had contact with Jewish religious centers in Babylonia and Palestine.[181] The Yemeni Himyarites converted to Judaism in the 4th century, and some of the Kinda were also converted in the 4th/5th century.[182] Jewish tribes existed in all major Arabian towns during Muhammad's time including in Tayma and Khaybar as well as Medina with twenty tribes living in the peninsula. From tomb inscriptions, it is visible that Jews also lived in Mada'in Saleh and Al-'Ula.[183]

There is evidence that Jewish converts in the Hejaz were regarded as Jews by other Jews, as well as by non-Jews, and sought advice from Babylonian rabbis on matters of attire and kosher food.[181] In at least one case, it is known that an Arab tribe agreed to adopt Judaism as a condition for settling in a town dominated by Jewish inhabitants.[181] Some Arab women in Yathrib/Medina are said to have vowed to make their child a Jew if the child survived, since they considered the Jews to be people "of knowledge and the book" (ʿilmin wa-kitābin).[181] Philip Hitti infers from proper names and agricultural vocabulary that the Jewish tribes of Yathrib consisted mostly of Judaized clans of Arabian and Aramaean origin.[109]

The key role played by Jews in the trade and markets of the Hejaz meant that market day for the week was the day preceding the Jewish Sabbath.[181] This day, which was called aruba in Arabic, also provided occasion for legal proceedings and entertainment, which in turn may have influenced the choice of Friday as the day of Muslim congregational prayer.[181] Toward the end of the sixth century, the Jewish communities in the Hejaz were in a state of economic and political decline, but they continued to flourish culturally in and beyond the region.[181] They had developed their distinctive beliefs and practices, with a pronounced mystical and eschatological dimension.[181] In the Islamic tradition, based on a phrase in the Quran, Arab Jews are said to have referred to Uzair as the son of Allah, although the historical accuracy of this assertion has been disputed.[26]

Jewish agriculturalists lived in the region of Eastern Arabia.[184][185] According to Robert Bertram Serjeant, the Baharna may be the Arabized "descendants of converts from Christians (Arameans), Jews and ancient Persians (Majus) inhabiting the island and cultivated coastal provinces of Eastern Arabia at the time of the Arab conquest".[180] From the Islamic sources, it seems that Judaism was the religion most followed in Yemen. Ya'qubi claimed all Yemenites to be Jews; Ibn Hazm however states only Himyarites and some Kindites were Jews.[179]

Christianity

The main areas of Christian influence in Arabia were on the north eastern and north western borders and in what was to become Yemen in the south.[186] The north west was under the influence of Christian missionary activity from the Roman Empire where the Ghassanids, a client kingdom of the Romans, were converted to Christianity.[187] In the south, particularly at Najran, a centre of Christianity developed as a result of the influence of the Christian Kingdom of Axum based on the other side of the Red Sea in Ethiopia.[186] Some of the Banu Harith had converted to Christianity. One family of the tribe built a large church at Najran called Deir Najran, also known as the "Ka'ba of Najran". Both the Ghassanids and the Christians in the south adopted Monophysitism.[186]

The third area of Christian influence was on the north eastern borders where the Lakhmids, a client tribe of the Sassanians, adopted Nestorianism, being the form of Christianity having the most influence in the Sassanian Empire.[186] As the Persian Gulf region of Arabia increasingly fell under the influence of the Sassanians from the early third century, many of the inhabitants were exposed to Christianity following the eastward dispersal of the religion by Mesopotamian Christians.[188] However, it was not until the fourth century that Christianity gained popularity in the region with the establishment of monasteries and a diocesan structure.[189]

In pre-Islamic times, the population of Eastern Arabia consisted of Christianized Arabs (including Abd al-Qays) and Aramean Christians among other religions.[177] Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.[190][191] Serjeant states that the Baharna may be the Arabized descendants of converts from the original population of Christians (Aramaeans), among other religions at the time of Arab conquests.[185] Beth Qatraye, which translates "region of the Qataris" in Syriac, was the Christian name used for the region encompassing north-eastern Arabia.[192][193] It included Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, Al-Hasa, and Qatar.[194] Oman and what is today the United Arab Emirates comprised the diocese known as Beth Mazunaye. The name was derived from 'Mazun', the Persian name for Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Sohar was the central city of the diocese.[192][194]

In Nejd, in the centre of the peninsula, there is evidence of members of two tribes, Kinda and Taghlib, converting to Christianity in the 6th century. However, in the Hejaz in the west, whilst there is evidence of the presence of Christianity, it is not thought to have been significant amongst the indigenous population of the area.[186]

Arabicized Christian names were fairly common among pre-Islamic Arabians, which has been attributed to the influence that Syrianized Christian Arabs had on Bedouins of the peninsula for several centuries before the rise of Islam.[195]

Neal Robinson, based on verses in the Quran, believes that some Arab Christians may have held unorthodox beliefs such as the worshipping of a divine triad of God the father, Jesus the Son and Mary the Mother.[196] Furthermore, there is evidence that unorthodox groups such as the Collyridians, whose adherents worshipped Mary, were present in Arabia, and it has been proposed that the Quran refers to their beliefs.[197] However, other scholars, notably Mircea Eliade, William Montgomery Watt, G. R. Hawting and Sidney H. Griffith, cast doubt on the historicity or reliability of such references in the Quran. Their views are as follows:

- Mircea Eliade argues that Muhammad's knowledge of Christianity "was rather approximative"[198] and that references to the triad of God, Jesus and Mary probably reflect the likelihood that Muhammad's information on Christianity came from people who had knowledge of the Monophysite Church of Abyssinia, which was known for extreme veneration of Mary.[198]

- William Montgomery Watt points out that we do not know how far Muhammad was acquainted with Christian beliefs prior to the conquest of Mecca and that dating of some of the passages criticizing Christianity is uncertain.[199] His view is that Muhammad and the early Muslims may have been unaware of some orthodox Christian doctrines, including the nature of the trinity, because Muhammad's Christian informants had a limited grasp of doctrinal issues.[200]

- Watt has also argued that the verses criticizing Christian doctrines in the Quran are attacking Christian heresies like tritheism and "physical sonship" rather than orthodox Christianity.[199][201]

- G. R. Hawting, Sidney H. Griffith and Gabriel Reynolds argue that the verses commenting on apparently unorthodox Christian beliefs should be read as an informed, polemically motivated caricature of mainstream Christian doctrine whose goal is to highlight how wrong some of its tenets appear from an Islamic perspective.[201]

See also

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Ancient Canaanite religion

- Book of Idols

- Hanif

- Religions of the ancient Near East

- Rahmanism

- Shirk (Islam)

- Taghut

References

Citations

- Hoyland 2002, p. 139.

- Berkey 2003, p. 42.

- Nicolle 2012, p. 19.

- Doniger 1999, p. 70.

- Mouton & Schmid 2014, p. 338.

- Teixidor 2015, p. 70.

- Peters 1994a, p. 6.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic", in McAuliffe 2005, pp. 92

- Teixidor 2015, p. 73-74.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic", in McAuliffe 2005, pp. 87

- Meyer-Hubbert 2016, p. 72.

- Aslan 2008, p. 6.

- Peters 1994b, p. 105.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 144.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 145.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 77.

- El-Zein 2009, p. 34.

- El-Zein 2009, p. 122.

- Lebling 2010, p. 96.

- Cramer 1979, p. 104.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic", in McAuliffe 2005, pp. 88

- Waardenburg 2003, p. 89.

- Campo 2009, p. 34.

- Hughes 2013, p. 25.

- Peters 1994b, p. 107.

- Robinson 2013, p. 75.

- Peters 1994b, p. 110.

- Peterson 2007, p. 21.

- Böwering, Gerhard, "God and his Attributes", in McAuliffe 2005

- Peterson 2007, p. 46.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 304–305

- Hitti 1970, p. 100-101.

- Phipps 1999, p. 21.

- Coulter & Turner 2013, p. 37.

- Guillaume 1963, p. 7.

- Corduan 2013, p. 112, 113.

- Rodinson 2002, p. 119.

- Taylor 2001, p. 130, 131, 162.

- Healey 2001, p. 110, 153.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 63.

- Frank & Montgomery 2007, p. 89.

- Hawting 1999, p. 142.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 44.

- Gilbert 2010, p. 8.

- Leeming 2004, p. 122.

- Coulter & Turner 2013, p. 317.

- Healey 2001, p. 112, 114.

- Corrente, Paola, "Dushara and Allāt alias Dionysos and Aphrodite in Herodotus 3.8", in Bernabé et al. 2013, pp. 265, 266

- Peters 2003, p. 45.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 140.

- Hirsch, Emil G.; Benzinger, Immanuel (1906). "Stone and Stone-Worship: Semitic Stone-Worship". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

The worship of sacred stones constituted one of the most general and ancient forms of religion; but among no other people was this worship so important as among the Semites. The religion of the nomads of Syria and Arabia was summarized by Clement of Alexandria in the single statement, "The Arabs worship the stone," and all the data afforded by Arabian authors regarding the pre-Islamitic faith confirm his words. The sacred stone ("nuṣb"; plural, "anṣab") is a characteristic and indispensable feature in an ancient Arabian place of worship. [...] When the Arabs offered bloody sacrifices the blood was smeared on the sacred stones, and in the case of offerings of oil the stones were anointed (comp. Gen. xxviii. 18, xxxi. 13). The same statement holds true of the Greco-Roman cult, although the black stone of Mecca, on the other hand, is caressed and kissed by the worshipers. In the course of time, however, the altar and the sacred stone were differentiated, and stones of this character were erected around the altar. Among both Canaanites and Israelites the maẓẓebah was separated from the altar, which thus became the place for the burning of the victim as well as for the shedding of its blood. That the altar was a development from the sacred stone is clearly shown by the fact that, in accordance with ancient custom, hewn stones might not be used in its construction.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 183.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 185.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 12-13.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic", in McAuliffe 2005, pp. 90

- Hoyland 2002, p. 157.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 158.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 159.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic", in McAuliffe 2005, pp. 89

- Hoyland 2002, p. 161.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 162.

- al-Azmeh 2017, p. 198.

- al-Azmeh 2017, p. 199.

- al-Azmeh 2017, p. 201.

- Peters 1994b, p. 96.

- Wheatley 2001, p. 366.

- al-Abbasi, Abeer Abdullah (August 2020). "The Arabsʾ Visions of the Upper Realm". Marburg Journal of Religion. University of Marburg. 22 (2): 1–28. doi:10.17192/mjr.2020.22.8301. ISSN 1612-2941. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 153.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 154.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 155.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 155-156.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 30.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 156.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 165.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 163.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 166.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 27.

- Crawford 1998, p. 79.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 142-144.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Before Himyar: Epigraphic evidence", in Fisher 2015, pp. 97–98

- Lurker 2015, p. 20.

- Korotaev 1996, p. 82.

- Lurker 2015, p. 26.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 141.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 1. Brill. p. 812.

- Hawting 1999, p. 125.

- Ancient Civilizations of Africa. 1981. p. 395. ISBN 9780435948054.

- Lurker 2015, p. 41.

- Ancient Civilizations of Africa. 1981. p. 397. ISBN 9780435948054.

- Finneran, Niall (2007-11-08). The Archaeology of Ethiopia. p. 180. ISBN 978-1136755521.

- Ancient Civilizations of Africa. 1981. pp. 352–353. ISBN 9780435948054.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 270

- Hoyland 2002, p. 50.

- al-Sa'ud 2011, p. 84.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 201.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 14.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 16.

- Healey & Porter 2003, p. 107.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 12.

- Peters 2017, p. 207.

- Healey & Porter 2003, p. 93.

- Peters 1994a, p. 5-7.

- Humphreys 1991, p. 69–71.

- Donner, Fred M., "The historical context", in McAuliffe 2006, pp. 33–34

- Humphreys 1991, p. 69-71.

- Humphreys 1991, p. 86–87.

- Humphreys 1991, p. 86-87.

- Lindsay 2005, p. 7.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 33–34.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 286–287

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 33-34.

- Armstrong 2000, p. 11.

- Peters 1994b, p. 108–109.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 30.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 33.

- Sykes 2014, p. 7.

- Fahd 2012.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 27-28.

- Coulter & Turner 2013, p. 305.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 303–304

- Peters 1994b, p. 106.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 297–299

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 302

- Hawting 1999, p. 1.

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson 2012, pp. 301

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 49.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 31.

- Peters 1994b, p. 169.

- Watt, Montgomery, "Muhammad", in Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 36

- Armstrong 2000, p. 23.

- Tabari 1990, p. 46.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 13-14, 25-26.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 207.

- Healey 2001, p. 126.

- Hoyland 2002, p. 132–136.

- Neusner 2006, p. 295.

- Teixidor 2015, p. 72.

- McLaughlin 2012, p. 124–125.

- Healey 2001, p. 89.

- Drijvers 1980, p. 154.

- Kaizer 2008, p. 87.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 51.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 9.

- Hawting 1999, p. 92.

- Paola Corrente (2013-06-26). Alberto Bernabé; Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui; Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal; Raquel Martín Hernández (eds.). Redefining Dionysos. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 263, 264. ISBN 9783110301328.

- Sartre 2005, p. 18.

- Taylor 2001, p. 126.

- Taylor 2001, p. 145.

- Rodinson 2002, p. 39.

- Chancey 2002, p. 136.

- Healey 2001, p. 169–175.

- Ball 2002, p. 67–68.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 36.

- Drijvers 1976, p. 4.

- Drijvers 1976, p. 21.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 81.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 82.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 84.

- Teixidor 1979, p. 68-69.

- al-Kalbi 2015, p. 42.

- AA.VV. Museo archeologico dei Campi Flegrei – Catalogo generale (vol. 2) – Pozzuoli, Electa Napoli 2008, pp. 60–63

- Robin, Christian Julien, "Before Himyar: Epigraphic evidence", in Fisher 2015, pp. 118

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 29.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 37.

- Carmody & Carmody 2015, p. 135.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 59–60.

- Tardieu, Michel (2008). Manichaeism, translated by DeBevoise.

- Tardieu, Michel. Les manichéens en Egypte. Bulletin de la Société Française d’Egyptologie.

- "Manichaeism Activity in Arabia".

That Manicheism went further on to the Arabian peninsula, up to the Hejaz and Mecca, where it could have possibly contributed to the formation of the doctrine of Islam, cannot be proven.

- Garry W. Strompf & Gunner Mikkelsen (2018). The Gnostic World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138673939.

Perhaps the charge of zandaqa functions in this report as a belated rhetorical caricature with no historical substance, much like the employment of congeners 'Manichee' and 'Gnostic' in the vocabulary of christian heresiography. If this is the case, historians can no longer appeal to the testimony of al-Kalbī as undisputable evidence for the proliferation of Manichaen-Doctrine in pre-islamic Mecca.

- Ibid Strompf & Mikkelsen et al.

This tradition is persistently echoed by later tradents ... whose values as independent witnesses to Manichaean activity in early seventh century Mecca are correspondingly suspect.

- Hughes 2013, p. 31, 32.

- Berkey 2003, p. 47, 48.

- Crone 2005, p. 371.

- Gelder 2005, p. 110.

- Stefon 2009, p. 36.

- Houtsma 1993, p. 98.

- Esposito 1999, p. 4.

- Lecker 1998, p. 20.

- Holes 2001, p. XXIV-XXVI.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 87–93.

- Shahid 1995, p. 265.

- Gilbert 2010, p. 2, 9.

- Smart 2013, p. 305.

- Holes 2001, p. XXIV–XXVI.

- Goddard 2000, p. 15–17.

- Berkey 2003, p. 44–46.

- Gilman & Klimkeit 1999, p. 87.

- Kozah & Abu-Husayn 2014, p. 55.

- Smart 1996, p. 305.

- Cameron 2002, p. 185.

- "Nestorian Christianity in the Pre-Islamic UAE and Southeastern Arabia", Peter Hellyer, Journal of Social Affairs, volume 18, number 72, winter 2011, p. 88

- "AUB academics awarded $850,000 grant for project on the Syriac writers of Qatar in the 7th century AD". American University of Beirut. 31 May 2011. Archived on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Kozah & Abu-Husayn 2014, p. 24.

- Zeitlin 2007, p. 35.

- Robinson 2013, p. 76.

- Sirry 2014, p. 46.

- Eliade 2013, p. 77.

- Watt 1956, p. 318.

- Watt 1956, p. 320.

- Sirry 2014, p. 47.

Sources

- Armstrong, Karen (2000), Islam: A Short History, Modern Library, ISBN 978-0-8129-6618-3

- Aslan, Reza (2008), No God but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam, Random House, ISBN 978-1-4070-0928-5

- al-Azmeh, Aziz (2017), The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-316-64155-2

- Ball, Warwick (2002), Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-82387-1

- Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003), The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3

- Bernabé, Alberto; Jáuregui, Miguel Herrero de; Cristóbal, Ana Isabel Jiménez San; Hernández, Raquel Martín, eds. (2013), Redefining Dionysos, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-030132-8

- Bukharin, Mikhail D. (2009). "Mecca On The Caravan Routes In Pre-Islamic Antiquity". In Marx, Michael; Neuwirth, Angelika; Sinai, Nicolai (eds.). The Qurʾān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 6. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 115–134. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176881.i-864.25. ISBN 978-90-04-17688-1. ISSN 1567-2808. S2CID 127529256.

- Cameron, Averil (2002), The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-98081-9

- Carmody, Denise Lardner; Carmody, John Tully (2015), In the Path of the Masters: Understanding the Spirituality of Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Muhammad: Understanding the Spirituality of Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Muhammad, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-46820-2

- Chancey, Mark A. (2002), The Myth of a Gentile Galilee, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-43465-2

- Corduan, Winfried (2013), Neighboring Faiths: A Christian Introduction to World Religions, InterVarsity Press, ISBN 978-0-8308-7197-1

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2013), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3

- Cramer, Marc (1979), The Devil Within, University of Michigan, ISBN 978-0-491-02366-5

- Crawford, Harriet E. W. (1998), Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbours, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-58679-5

- Crone, Patricia (2005), Medieval Islamic Political Thought, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-2194-1

- El-Zein, Amira (2009), Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0-8156-3200-9

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0

- Drijvers, H. J. W (1976). van Baaren, Theodoor Pieter; Leertouwer, Lammert; Leemhuis, Fred; Buning, H. (eds.). The Religion of Palmyra. Brill. ISBN 978-0-585-36013-3.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1980), Cults and Beliefs at Edessa, Brill Archive, ISBN 978-90-04-06050-0

- Eliade, Mircea (2013), History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-14772-7

- Esposito, John (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510799-9

- Fahd, T. (2012). "Manāf". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_4901. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- Fisher, Greg (2015), Arabs and Empires before Islam, OUP Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-105699-4

- Finster, Barbara (2009). "Arabia In Late Antiquity: An Outline of The Cultural Situation In The Peninsula At The Time of Muhammad". In Marx, Michael; Neuwirth, Angelika; Sinai, Nicolai (eds.). The Qurʾān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 6. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 61–114. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176881.i-864.21. ISBN 978-90-04-17688-1. ISSN 1567-2808. S2CID 160525414.

- Frank, Richard M.; Montgomery, James Edward (2007), Arabic Theology, Arabic Philosophy: From the Many to the One, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 978-90-429-1778-1

- Gelder, G. J. H. van (2005), Close Relationships: Incest and Inbreeding in Classical Arabic Literature, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-85043-855-7

- Gilbert, Martin (2010), In Ishmael's House: A History of Jews in Muslim Lands, McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 978-1-55199-342-3

- Gilman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (2013), Christians in Asia before 1500, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-10978-2

- Goddard, Hugh (2000), A History of Christian-Muslim Relations, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-1-56663-340-6

- Guillaume, Alfred (1963), Islam, Cassell

- Hawting, G. R. (1999), The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-42635-0

- Healey, John F. (2001), The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10754-0

- Healey, John F.; Porter, Venetia (2003), Studies on Arabia in Honour of G. Felix, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-851064-2

- Holes, Clive (2001), Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10763-2

- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor, ed. (1993), E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 5, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2002), Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-64634-0

- Hughes, Aaron W. (2013), "Setting the Stage: Pre-Islamic Arabia", Muslim Identities: An Introduction to Islam, Columbia University Press, pp. 17–40, ISBN 978-0-231-53192-4

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1991), Islamic History: A Framework for Inquiry, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-85043-360-6

- Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (2012), The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, OUP USA, ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1

- Kaizer, Ted (2008), The Variety of Local Religious Life in the Near East: In the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16735-3

- al-Kalbi, Hisham Ibn (2015), Book of Idols, translated by Faris, Nabih Amin, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-7679-2

- Korotayev, A. V. (1996), Pre-Islamic Yemen: Socio-political Organization of the Sabaean Cultural Area in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries AD, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-03679-5

- Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim (2014), The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century, Gorgias Press, LLC, ISBN 978-1-4632-0355-9

- Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977), The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1A, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4

- Lindsay, James E. (2005), Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32270-9

- Lurker, Manfred (2015), A Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-10628-6

- Lecker, Michael (1998), Jews and Arabs in Pre- and Early Islamic Arabia, Ashgate, ISBN 978-0-86078-784-6

- Leeming, David Adams (2004), Jealous Gods and Chosen People: The Mythology of the Middle East, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-534899-6

- McLaughlin, John L. (2012), The Ancient Near East, Abingdon Press, ISBN 978-1-4267-6550-6

- Meyer-Hubbert, Katarzyna Aleksandra (2016), Un(Rein) zum Gebet? Zu den islamischen Religionsnormierungen des Ortes, der Kleidung und der Intention in ihrem interkulturellen Entstehungsraum, Hochschule des Bundes für öffentliche Verwaltung

- Mir, Mustansir (2006). "Polytheism and Atheism". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. IV. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQCOM_00151. ISBN 978-90-04-14743-0.

- Mouton, Michel; Schmid, Stephan G. (2014), Men on the Rocks: The Formation of Nabataean Petra, Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH, ISBN 978-3-8325-3313-7

- Neusner, Jacob (2006), Jeremiah in Talmud and Midrash: A Source Book, University Press of America, ISBN 978-0-7618-3487-8

- Nicolle, David (2012), The Great Islamic Conquests AD 632-750, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-78096-998-5

- Peters, Francis Edward (1994a), Mecca: A Literary History of the Muslim Holy Land, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-03267-2

- Peters, Francis Edward (1994b), Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1875-8

- Peters, Francis Edward (2003), Islam, a Guide for Jews and Christians, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-11553-5

- Peterson, Daniel C. (2007), Muhammad, Prophet of God, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0

- Phipps, William E. (1999), Muhammad and Jesus: A Comparison of the Prophets and Their Teachings, A&C Black, ISBN 978-0-8264-1207-2

- Robin, Christian Julien (2006). "South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. V. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQCOM_00189. ISBN 90-04-14743-8.

- Robinson, Neal (1991). Christ in Islam and Christianity: The Representation of Jesus in the Qur'an and the Classical Muslim Commentaries. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0558-1. S2CID 169122179.

- Robinson, Neal (2013), Islam: A Concise Introduction, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-81773-1

- Rodinson, Maxime (2002), Muhammad: Prophet of Islam, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, ISBN 978-1-86064-827-4

- al-Sa'ud, 'Abd Allah Sa'ud (2011), Central Arabia During the Early Hellenistic Period, King Fahd National Library, ISBN 978-9-960-00097-8

- Sartre, Maurice (2005), The Middle East Under Rome, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01683-5

- Seidensticker, Tilman (2009). "Sources For The History of Pre-Islamic Religion". In Marx, Michael; Neuwirth, Angelika; Sinai, Nicolai (eds.). The Qurʾān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 6. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 293–322. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176881.i-864.66. ISBN 978-90-04-17688-1. ISSN 1567-2808. S2CID 161557309.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995), Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Dumbarton Oaks, ISBN 978-0-88402-284-8

- Sirry, Mun'im (2014), Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-935937-0

- Smart, J. R. (1996), Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language and Literature, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-7007-0411-8