Reception history of Jane Austen

The reception history of Jane Austen follows a path from modest fame to wild popularity. Jane Austen (1775–1817), the author of such works as Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Emma (1815), has become one of the best-known and most widely read novelists in the English language.[1] Her novels are the subject of intense scholarly study and the centre of a diverse fan culture.

Jane Austen | |

|---|---|

_hires.jpg.webp) A watercolour and pencil sketch of Austen, believed to have been drawn from life by her sister Cassandra (c. 1810) | |

| Born | 16 December 1775 Steventon Rectory, Hampshire |

| Died | 18 July 1817 (aged 41) Winchester, Hampshire |

| Resting place | Winchester Cathedral, Hampshire |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 1787 to 1809–1811 |

| Genres | Comedy of Manners, Romance |

| Signature | |

During her lifetime, Austen's novels brought her little personal fame. Like many women writers, she chose to publish anonymously, but her authorship was an open secret. At the time they were published, Austen's works were considered fashionable, but received only a few reviews, albeit positive. By the mid-19th century, her novels were admired by members of the literary elite who viewed their appreciation of her works as a mark of cultivation, but they were also being recommended in the popular education movement and on school reading lists as early as 1838. The first illustrated edition of her works appeared in 1833, in Richard Bentley's Standard Novels series, which put her titles before thousands of readers across the Victorian period.[2]

The publication in 1870 of her nephew's Memoir of Jane Austen introduced her to a wider public as an appealing personality—dear aunt Jane—and her works were republished in popular editions. By the start of the 20th century, competing groups had sprung up—some to worship her and some to defend her from the "teeming masses"—but all claiming to be the true Janeites, or those who properly appreciated her. The "teeming masses", meanwhile, were creating their own ways of honouring Austen, including in amateur theatricals in drawing rooms, schools, and community groups.[3]

In 1923, the publisher and scholar R. W. Chapman prepared a carefully edited collection of her works, which some have claimed is the first serious scholarly treatment given to any British novelist. By mid-century, Austen was widely accepted within academia as a great English novelist. The second half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Austen scholarship, which explored numerous aspects of her works: artistic, ideological, and historical. With the growing professionalisation of university English departments in the second half of the 20th century, criticism of Austen became more theoretical and specialized, as did literary studies in general. As a result, commentary on Austen sometimes seemed to imagine itself as divided into high culture and popular culture branches. In the mid- to late 20th century, fans founded Jane Austen societies and clubs to celebrate the author, her time, and her works. As of the early 21st century, Austen fandom supports an industry of printed sequels and prequels as well as television and film adaptations, which started with the 1940 film Pride and Prejudice and evolved to include productions such as the 2004 Bollywood-style film Bride and Prejudice.

On November 5, 2019, the BBC News listed Pride and Prejudice on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[4]

Background

_-_Sense_and_Sensibility.jpg.webp)

Jane Austen lived her entire life as part of a large and close-knit family on the lower fringes of the English gentry.[5] Her family's steadfast support was critical to Austen's development as a professional writer.[6] Austen read draft versions of all of her novels to her family, receiving feedback and encouragement,[7] and it was her father who sent out her first publication bid.[8] Austen's artistic apprenticeship lasted from her teenage years until she was about thirty-five. During this period, she experimented with various literary forms, including the epistolary novel which she tried and then abandoned, and wrote and extensively revised three major novels and began a fourth. With the release of Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1815), she achieved success as a published writer.

Novel-writing was a suspect occupation for women in the early 19th century, because it imperiled their social reputation by bringing them publicity, viewed as unfeminine. Therefore, like many other female writers, Austen published anonymously.[9] Eventually, though, her novels' authorship became an open secret among the aristocracy.[10] During one of her visits to London, the Prince Regent invited her, through his librarian, James Stanier Clarke, to view his library at Carlton House; his librarian mentioned that the Regent admired her novels and that "if Miss Austen had any other Novel forthcoming, she was quite at liberty to dedicate it to the Prince".[11] Austen, who disapproved of the prince's extravagant lifestyle, did not want to follow this suggestion, but her friends convinced her otherwise: in short order, Emma was dedicated to him. Austen turned down the librarian's further hint to write a historical romance in honour of the prince's daughter's marriage.[12]

In the last year of her life, Austen revised Northanger Abbey (1817), wrote Persuasion (1817), and began another novel, eventually titled Sanditon, which was left unfinished at her death. Austen did not have time to see Northanger Abbey or Persuasion through the press, but her family published them as one volume after her death, and her brother Henry included a "Biographical Notice of the Author".[13] This short biography sowed the seeds for the myth of Austen as a quiet, retiring aunt who wrote during her spare time: "Neither the hope of fame nor profit mixed with her early motives ... [S]o much did she shrink from notoriety, that no accumulation of fame would have induced her, had she lived, to affix her name to any productions of her pen ... in public she turned away from any allusion to the character of an authoress."[14] However, this description is in direct contrast to the excitement Austen shows in her letters regarding publication and profit: Austen was a professional writer.[15]

Austen's works are noted for their realism, biting social commentary, and masterful use of free indirect discourse, burlesque and irony.[16] They critique the novels of sensibility of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century realism.[17] As Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert explain, Austen makes fun of "such novelistic clichés as love at first sight, the primacy of passion over all other emotions and/or duties, the chivalric exploits of the hero, the vulnerable sensitivity of the heroine, the lovers' proclaimed indifference to financial considerations, and the cruel crudity of parents".[18] Austen's plots, though comic,[19] highlight the way women of the gentry depended on marriage to secure social standing and economic security.[20] Like the writings of Samuel Johnson, a strong influence on her, her works are fundamentally concerned with moral issues.[21]

1812–1821: Individual reactions and contemporary reviews

Austen's novels quickly became fashionable among opinion-makers, namely, those aristocrats who often dictated fashion and taste. Lady Bessborough, sister to the notorious Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, commented on Sense and Sensibility in a letter to a friend: "it is a clever novel. ... tho' it ends stupidly, I was much amused by it."[22] The fifteen-year-old daughter of the Prince Regent, Princess Charlotte Augusta, compared herself to one of the book's heroines: "I think Marianne & me are very like in disposition, that certainly I am not so good, the same imprudence, &tc".[23]

After reading Pride and Prejudice, playwright Richard Sheridan advised a friend to "[b]uy it immediately" for it "was one of the cleverest things" he had ever read.[24] Anne Milbanke, future wife of the Romantic poet Lord Byron, wrote: "I have finished the Novel called Pride and Prejudice, which I think a very superior work." She commented that the novel "is the most probable fiction I have ever read" and had become "at present the fashionable novel".[25] The Dowager Lady Vernon told a friend that Mansfield Park was "[n]ot much of a novel, more the history of a family party in the country, very natural"—as if, comments one Austen scholar, "Lady Vernon's parties mostly featured adultery."[26] Lady Anne Romilly told her friend, the novelist Maria Edgeworth, that "[Mansfield Park] has been pretty generally admired here" and Edgeworth commented later that "we have been much entertained with Mansfield Park".[26]

Despite these positive reactions from the elite, Austen's novels received relatively few reviews during her lifetime:[27] two for Sense and Sensibility, three for Pride and Prejudice, none for Mansfield Park, and seven for Emma. Most of the reviews were short and on balance favourable, although superficial and cautious.[28] They most often focused on the moral lessons of the novels.[29] Moreover, as Brian Southam, who has edited the definitive volumes on Austen's reception, writes in his description of these reviewers, "their job was merely to provide brief notices, extended with quotations, for the benefit of women readers compiling their library lists and interested only in knowing whether they would like a book for its story, its characters and moral".[30] This was not atypical critical treatment for novels in Austen's day.

Asked by publisher John Murray to review Emma, famed historical novelist Walter Scott wrote the longest and most thoughtful of these reviews, which was published anonymously in the March 1816 issue of the Quarterly Review. Using the review as a platform from which to defend the then disreputable genre of the novel, Scott praised Austen's works, celebrating her ability to copy "from nature as she really exists in the common walks of life, and presenting to the reader ... a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him".[31] Modern Austen scholar William Galperin has noted that "unlike some of Austen's lay readers, who recognized her divergence from realistic practice as it had been prescribed and defined at the time, Walter Scott may well have been the first to install Austen as the realist par excellence".[32] Scott wrote in his private journal in 1826, in what later became a widely quoted comparison:

Also read again, and for the third time at least, Miss Austen's very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The Big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going; but the exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting, from the truth of the description and the sentiment, is denied to me. What a pity such a gifted creature died so early![33]

Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, published together posthumously in December 1817, were reviewed in the British Critic in March 1818 and in the Edinburgh Review and Literary Miscellany in May 1818. The reviewer for the British Critic felt that Austen's exclusive dependence on realism was evidence of a deficient imagination. The reviewer for the Edinburgh Review disagreed, praising Austen for her "exhaustless invention" and the combination of the familiar and the surprising in her plots.[34] Overall, Austen scholars have pointed out that these early reviewers did not know what to make of her novels—for example, they misunderstood her use of irony. Reviewers reduced Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice to didactic tales of virtue prevailing over vice.[35]

In the Quarterly Review in 1821, the English writer and theologian Richard Whately published the most serious and enthusiastic early posthumous review of Austen's work. Whately drew favourable comparisons between Austen and such acknowledged greats as Homer and Shakespeare, praising the dramatic qualities of her narrative. He also affirmed the respectability and legitimacy of the novel as a genre, arguing that imaginative literature, especially narrative, was more valuable than history or biography. When it was properly done, as in Austen, Whately said, imaginative literature concerned itself with generalised human experience from which the reader could gain important insights into human nature; in other words, it was moral.[36] Whately also addressed Austen's position as a female writer, writing: "we suspect one of Miss Austin's [sic] great merits in our eyes to be, the insight she gives us into the peculiarities of female characters. ... Her heroines are what one knows women must be, though one never can get them to acknowledge it."[37] No more significant, original Austen criticism was published until the late 19th century: Whately and Scott had set the tone for the Victorian era's view of Austen.[36]

1821–1870: Cultured few

Austen had many admiring readers during the 19th century who, according to critic Ian Watt, appreciated her "scrupulous ... fidelity to ordinary social experience".[38] However, Austen's novels did not conform to certain strong Romantic and Victorian British preferences, which required that "powerful emotion [be] authenticated by an egregious display of sound and colour in the writing".[39] Victorian critics and audiences were drawn to the work of authors such as Charles Dickens and George Eliot; by comparison, Austen's novels seemed provincial and quiet.[40] Although Austen's works were republished beginning in late 1832 or early 1833 by Richard Bentley in the Standard Novels series, and remained in print continuously thereafter, they were not best-sellers.[41] Southam describes her "reading public between 1821 and 1870" as "minute beside the known audience for Dickens and his contemporaries".[42]

Those who did read Austen saw themselves as discriminating readers—they were a cultured few. This became a common theme of Austen criticism during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[43] Philosopher and literary critic George Henry Lewes articulated this theme in a series of enthusiastic articles in the 1840s and 1850s. In "The Novels of Jane Austen", published anonymously in Blackwood's Magazine in 1859, Lewes praised Austen's novels for "the economy of art ... the easy adaptation of means to ends, with no aid from superfluous elements" and compared her to Shakespeare.[44] Arguing that Austen lacked the ability to construct a plot, he still celebrated her dramatisations: "The reader's pulse never throbs, his curiosity is never intense; but his interest never wanes for a moment. The action begins; the people speak, feel, and act; everything that is said, felt, or done tends towards the entanglement or disentanglement of the plot; and we are almost made actors as well as spectators of the little drama."[45]

Reacting against Lewes's essays and his personal communications with her, novelist Charlotte Brontë admired Austen's fidelity to everyday life but described her as "only shrewd and observant" and criticised the absence of visible passion in her work.[46] To Brontë, Austen's work appeared formal and constrained, "a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of bright vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck".[47]

19th-century European translations

Austen's novels appeared in some European countries soon after their publication in Britain, beginning in 1813 with a French translation of Pride and Prejudice in the journal Bibliothèque Britannique, quickly followed by German, Danish, and Swedish editions. Their availability in Europe was not universal. Austen was not well known in Russia and the first Russian translation of an Austen novel did not appear until 1967.[48] Despite the fact that Austen's novels were translated into many European languages, Europeans did not recognise her works as part of the English novel tradition. This perception was reinforced by the changes made by translators who injected sentimentalism into Austen's novels and eliminated their humour and irony. European readers therefore more readily associated Walter Scott's style with the English novel.[49]

Because of the significant changes made by her translators, Austen was received as a different kind of novelist in continental Europe than in Britain.[50] In Bibliothèque Britannique's Pride and Prejudice, for example, vivacious conversations between Elizabeth and Darcy were replaced by decorous ones.[51] Elizabeth's claim that she has "always seen a great similarity in the turn of [their] minds" (her and Darcy's) because they are "unwilling to speak, unless [they] expect to say something that will amaze the whole room" becomes "Moi, je garde le silence, parce que je ne sais que dire, et vous, parce que vous aiguisez vos traits pour parler avec effet." ("Me, I keep silent, because I don't know what to say, and you, because you excite your features for effect when speaking.") As Cossy and Saglia explain in their essay on Austen translations, "the equality of mind which Elizabeth takes for granted is denied and gender distinction introduced".[51] Because Austen's works were seen in France as part of a sentimental tradition, they were overshadowed by the works of French realists such as Stendhal, Balzac, and Flaubert.[52] German translations and reviews of those translations also placed Austen in a line of sentimental writers, particularly late Romantic women writers.[53]

A study of other important dimensions of some French translations, such as free indirect discourse, do much to nuance our understanding of Austen's initial "aesthetic" reception with her first French readership.[54] Austen uses the narrative technique of free indirect discourse to represent Anne Elliot's consciousness in Persuasion. Indeed, the portrayal of the heroine's subjective experience is central to its narration.[55] The frequent use of the technique imbues Persuasion's narrative discourse with a high degree of subtlety, placing a huge burden of interpretation on Austen's first translators. Recent studies demonstrate that free indirect discourse from Persuasion was translated extensively in Isabelle de Montolieu's La Famille Elliot.[56] Indeed, the translator, herself a novelist, was aware of the propensity of Austen's narrator to delve into the heroine's psychology in Persuasion as she comments on this in the preface to La Famille Elliot. She characterises it as "almost imperceptible, delicate nuances that come from the heart": des nuances délicates presque imperceptibles qui partent du fond du cœur, et dont miss JANE AUSTEN avait le secret plus qu'aucun autre romancier.[57] Montolieu's extensive translations of Austen's technique concerning discourse demonstrate that she was in fact one of Austen's first critical readers, whose own finely nuanced reading of Austen's narrative technique meant that her first French readers could also share in Anne Elliot's psychological drama in much the same way that her English readership could.[58]

1870–1930: Explosion in popularity

Family biographies

.jpg.webp)

For decades, Scott's and Whately's opinions dominated the reception of Austen's works and few people read her novels. In 1869, this changed with the publication of the first significant Austen biography, A Memoir of Jane Austen, which was written by Jane Austen's nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh.[59] With its release, Austen's popularity and critical standing increased dramatically.[60] Readers of the Memoir were presented with the myth of the amateur novelist who wrote masterpieces: the Memoir fixed in the public mind a sentimental picture of Austen as a quiet, middle-aged maiden aunt and reassured them that her work was suitable for a respectable Victorian family. James Edward Austen-Leigh had a portrait of Jane Austen painted, based on the earlier watercolour, softening her image and making her presentable to the Victorian public.[61] The engraving by Bentley which formed the frontispiece of Memoir is based on the idealised image.

The publication of the Memoir spurred a major reissue of Austen's novels. The first popular editions were released in 1883—a cheap sixpenny series published by Routledge. This was followed by a proliferation of elaborate illustrated editions, collectors' sets, and scholarly editions.[62] However, contemporary critics continued to assert that her works were sophisticated and only appropriate for those who could truly plumb their depths.[63] Yet, after the publication of the Memoir, more criticism was published on Austen's novels in two years than had appeared in the previous fifty.[64]

In 1913, William Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh, descendants of the Austen family, published the definitive family biography, Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters – A Family Record. Based primarily on family papers and letters, it is described by Austen biographer Park Honan as "accurate, staid, reliable, and at times vivid and suggestive".[65] Although the authors moved away from the sentimental tone of the Memoir, they made little effort to go beyond the family records and traditions immediately available to them. Their book therefore offers bare facts and little in the way of interpretation.[66]

Criticism

During the last quarter of the 19th century, the first books of critical analysis regarding Austen's works were published. In 1890 Goldwin Smith published the Life of Jane Austen, initiating a "fresh phase in the critical heritage", in which Austen reviewers became critics. This launched the beginning of "formal criticism", that is, a focus on Austen as a writer and an analysis of the techniques that made her writing unique.[67] According to Southam, while Austen criticism increased in amount and, to some degree, in quality after 1870, "a certain uniformity" pervaded it:

We see the novels praised for their elegance of form and their surface 'finish'; for the realism of their fictional world, the variety and vitality of their characters; for their pervasive humour; and for their gentle and undogmatic morality and its unsermonising delivery. The novels are prized for their 'perfection'. Yet it is seen to be a narrow perfection, achieved within the bounds of domestic comedy.[68]

Among the most astute of these critics were Richard Simpson, Margaret Oliphant, and Leslie Stephen. In a review of the Memoir, Simpson described Austen as a serious yet ironic critic of English society. He introduced two interpretative themes which later became the basis for modern literary criticism of Austen's works: humour as social critique and irony as a means of moral evaluation. Continuing Lewes's comparison to Shakespeare, Simpson wrote that Austen:

began by being an ironical critic; she manifested her judgment ... not by direct censure, but by the indirect method of imitating and exaggerating the faults of her models. ... Criticism, humour, irony, the judgment not of one that gives sentence but of the mimic who quizzes while he mocks, are her characteristics.[69]

Simpson's essay was not well known and did not become influential until Lionel Trilling quoted it in 1957.[70] Another prominent writer whose Austen criticism was ignored, novelist Margaret Oliphant, described Austen in almost proto-feminist terms, as "armed with a 'fine vein of feminine cynicism,' 'full of subtle power, keenness, finesse, and self-restraint,' blessed with an 'exquisite sense' of the 'ridiculous,' 'a fine stinging yet soft-voiced contempt,' whose novels are 'so calm and cold and keen'".[71] This line of criticism would not be fully explored until the 1970s with the rise of feminist literary criticism.

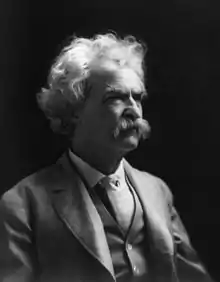

Although Austen's novels had been published in the United States since 1832, albeit in bowdlerised editions, it was not until after 1870 that there was a distinctive American response to Austen.[72] As Southam explains, "for American literary nationalists Jane Austen's cultivated scene was too pallid, too constrained, too refined, too downright unheroic".[73] Austen was not democratic enough for American tastes and her canvas did not extend to the frontier themes that had come to define American literature.[73] By the start of the 20th century, the American response was represented by the debate between the American novelist and critic William Dean Howells and the writer and humourist Mark Twain. In a series of essays, Howells helped make Austen into a canonical figure for the populace whereas Twain used Austen to argue against the Anglophile tradition in America. That is, Twain argued for the distinctiveness of American literature by attacking English literature.[74] In his book Following the Equator, Twain described the library on his ship: "Jane Austen's books ... are absent from this library. Just that one omission alone would make a fairly good library out of a library that hadn't a book in it."[75]

The critic H. L. Mencken did not like Austen either. Late in life he read Austen for the first time. He wrote, "It was not until the Spring of 1945, when I was approaching 65, that I ever came to Jane Austen. My choice, naturally, was "Mansfield Park," for all the authorities seemed to agree that it was Jane's best... [It] was extraordinarily stiff and clumsy, and even in moments of high passion the people of the tale had at one another with set speeches, many of them so ornate as to be almost unintelligible. I got as far as Chapter XXXIX and then had to give up, thus missing altogether the elopement of Crawford and Mrs. Rushworth. It was a somewhat painful experience, and I had to console myself with the reflection that novel-writing has made enormous progress since the first days of the Nineteenth Century."[76]

Janeites

Might we not ... borrow from Miss Austen's biographer the title which the affection of a nephew bestows upon her, and recognise her officially as 'dear aunt Jane'?

– Richard Simpson[77]

The Encyclopædia Britannica's changing entries on Austen illustrate her increasing popularity and status. The eighth edition (1854) described her as "an elegant novelist" while the ninth edition (1875) lauded her as "one of the most distinguished modern British novelists".[78] Around the start of the 20th century, Austen novels began to be studied at universities and appear in histories of the English novel.[79] The image of her that dominated the popular imagination was still that first presented in the Memoir and made famous by Howells in his series of essays in Harper's Magazine, that of "dear aunt Jane".[80] Author and critic Leslie Stephen described a mania that started to develop for Austen in the 1880s as "Austenolatry"[81]—it was only after the publication of the Memoir that readers developed a personal connection with Austen.[82] However, around 1900, members of the literary elite, who had claimed an appreciation of Austen as a mark of culture, reacted against this popularisation of her work. They referred to themselves as Janeites to distinguish themselves from the masses who, in their view, did not properly understand Austen.[83]

American novelist Henry James, one member of this literary elite, referred to Austen several times with approval and on one occasion ranked her with Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Henry Fielding as among "the fine painters of life".[84] But James thought Austen an "unconscious" artist whom he described as "instinctive and charming".[85] In 1905, James responded frustratingly to what he described as "a beguiled infatuation" with Austen, a rising tide of public interest that exceeded Austen's "intrinsic merit and interest". James attributed this rise principally to "the stiff breeze of the commercial, ... the special bookselling spirits. ... the body of publishers, editors, illustrators, producers of the pleasant twaddle of magazines; who have found their 'dear', our dear, everybody's dear, Jane so infinitely to their material purpose, so amenable to pretty reproduction in every variety of what is called tasteful, and in what seemingly proves to be salable, form."[86]

In an effort to avoid the sentimental image of the "Aunt Jane" tradition and approach Austen's fiction from a fresh perspective, in 1917 British intellectual and travel writer Reginald Farrer published a lengthy essay in the Quarterly Review which Austen scholar A. Walton Litz calls the best single introduction to her fiction.[87] Southam describes it as a "Janeite" piece without the worship.[88] Farrer denied that Austen's artistry was unconscious (contradicting James) and described her as a writer of intense concentration and a severe critic of her society, "radiant and remorseless", "dispassionate yet pitiless", with "the steely quality, the incurable rigor of her judgment".[89] Farrer was one of the first critics who viewed Austen as a subversive writer.[90]

1930–2000: Modern scholarship

Several important early works—glimmers of brilliant Austen scholarship—paved the way for Austen to become solidly entrenched within the academy. The first was Oxford Shakespearean scholar A. C. Bradley's 1911 essay, "generally regarded as the starting-point for the serious academic approach to Jane Austen".[92] Bradley emphasised Austen's ties to 18th-century critic and writer Samuel Johnson, arguing that she was a moralist as well as humourist; in this he was "totally original", according to Southam.[93] Bradley divided Austen's works into "early" and "late" novels, categories still used by scholars.[94] The second path-breaking early-20th-century critic of Austen was R. W. Chapman, whose magisterial edition of Austen's collected works was the first scholarly edition of the works of any English novelist. The Chapman texts have remained the basis for all subsequent editions of Austen's works.[95]

In the wake of Bradley and Chapman's contributions, the 1920s saw a boom in Austen scholarship, and the novelist E. M. Forster primarily illustrated his concept of the "round" character by citing Austen's works. It was with the 1939 publication of Mary Lascelles' Jane Austen and Her Art—"the first full-scale historical and scholarly study" of Austen—that the academic study of her works matured.[96] Lascelles included a short biographical essay; an innovative analysis of the books Austen read and their effect on her writing; and an extended analysis of Austen's style and her "narrative art". Lascelles felt that prior critics had all worked on a scale "so small that the reader does not see how they have reached their conclusions until he has patiently found his own way to them".[97] She wished to examine all Austen's works together and to subject her style and techniques to methodical analysis. Lascelles praised Austen for her "shallow modelling" of her characters, giving them distinctive voices yet making certain it was clear they all belonged to the same class.[98] Subsequent critics agree that she succeeded. Like Bradley earlier, she emphasised Austen's connection to Samuel Johnson and her desire to discuss morality through fiction. However, at the time some fans of Austen worried that academics were taking over Austen criticism and that it was becoming increasingly esoteric—a debate that continued into the 21st century.[99]

In an outpouring of mid-century revisionist views, scholars approached Austen more sceptically. D. W. Harding, following and expanding upon Farrer, argued in his essay "Regulated Hatred: An Aspect of the Work of Jane Austen" that Austen's novels did not support the status quo but rather subverted it. Her irony was not humorous but caustic and intended to undermine the assumptions of the society she portrayed. Through her use of irony, Austen attempted to protect her integrity as an artist and a person in the face of attitudes and practices she rejected.[100] In his 1940 essay, Harding argued that Austen had to be rescued from the Janites, charging "her books are, as she meant them to be, read and enjoyed by precisely the sort of people she disliked".[101] Harding argued the Janites regarded Regency England as "expressing the gentler virtue of a civilised social order" that was an escape from the waking nightmare of a world at war, but he argued that in its own sort of way that the world of Austen's novels was nightmarish, where the government maintained a system of spies to crush any sympathy with the French Revolution, where friends take delight in causing others pain, where the polite language is usually a facade, and where intelligence in single women is seen as a problem.[102] Harding maintained that the problem with the Janites was that they could not grasp these aspects of Austen's works.[102] Almost simultaneously, influential critic Q. D. Leavis argued in "Critical Theory of Jane Austen's Writing", published in Scrutiny in the early 1940s, that Austen was a professional, not an amateur, writer.[103] Harding's and Leavis's articles were followed by another revisionist treatment by Marvin Mudrick in Jane Austen: Irony as Defense and Discovery (1952). Mudrick portrayed Austen as isolated, defensive, and critical of her society, and described in detail the relationship he saw between Austen's attitude toward contemporary literature and her use of irony as a technique to contrast the realities of her society with what she felt they should be.[100] These revisionist views, together with prominent critic F. R. Leavis's pronouncement in The Great Tradition (1948) that Austen was one of the great writers of English fiction, a view shared by Ian Watt, who helped shape the scholarly debate regarding the genre of the novel, did much to cement Austen's reputation amongst academics.[104] They agreed that she "combined [Henry Fielding's and Samuel Richardson's] qualities of interiority and irony, realism and satire to form an author superior to both".[105]

The period after the Second World War saw a flowering of scholarship on Austen as well as a diversity of critical approaches. One school that emerged in the United States was the New Criticism, which saw literary texts in only aesthetic terms, an object of beauty to be appreciated in and of itself without any study of the individual that had produced it or the society that she lived in.[98] The New Critics tended to praise Austen for her literary skills at combining irony and paradox. But others said that New Criticism's focus on the aesthetic qualities of the books ignored their message, and reduced Austen to merely the scribe of these books that they admired so much.[106] More typical of the post-1945 scholarship is Marvin Mudrick's 1952 book Jane Austen: Irony as Defense and Discovery, where he argued that Austen used irony as a way of deflating conventions and to gently challenge the reader's beliefs.[107]

In 1951, Arnold Kettle in his Introduction to the English Novel praised Austen for her "fineness of feeling", but complained about the "relevance" of her work to the 20th century, charging that the values of Austen's novels were too much those of Regency England to be acceptable for the 20th century, writing that a modern audience could not accept the rigidly hierarchical society of her time where the vast majority of people were denied the right to vote.[108] About the question of the "relevance" of Austen to the modern world, the American critic Lionel Trilling in his 1955 essay on Mansfield Park wrote about the problem of existing in the modern world, of "the terrible strain it imposes on us...the exhausting effort which the concept of personality requires us to make", and praised Austen for her refusal to dignify the "uncertainty and difficulty" of modern life, praising her irony as the "engaging manner by which she masks society's crude coercive power", and uses irony in a "generosity of spirit".[109] In his 1957 essay "Emma and the Legend of Jane Austen", Trilling argued that Austen was the first novelist to handle the very modern problem of the "deep psychological change which accompanied the establishment of democratic society" which imposed a "psychological burden" on an individual which the "new necessity of conscious self-definition and self-criticism", as "there is no reality about which the modern person is more uncertain and more anxious than the reality of himself".[110] Trilling argued that in modern society, where people existed only as "atoms" uncertain about how they really were, Austen offers us a "rare hope" of a world where people could define themselves on their own terms.[111]

Ian Watt in his 1957 book The Rise of the Novel argued that 18th century British literature was characterized by a dichotomy between either novels that were told from the first person and novels from the third person; the significance of Austen rested according to Watt in her ability to combine both subjective and objective tendencies in her books though her use of free indirect discourse.[112] Another influential work was Wayne Booth's 1961 book The Rhetoric of Fiction, in which he offered a detailed study of Emma, which he argued was told from three points of view; Emma's, Mr. Knightley's and the unnamed narrator.[113] Booth argued that Austen adopted this three-fold narration because Emma is in many ways an unlikable character, a spoiled and immature busybody, and Austen had to find a way to make her likable and engaging to the reader.[114] Booth's book was widely praised for the way in which he highlighted how a moral problem (Emma's character) was turned into an aesthetic problem (how to tell the story while keeping its protagonist likable enough to engage the reader's sympathy), and has been the basis of much Austen scholarship since.[113] Critics like Graham Hough have pointed out that the morality of the characters in Emma is related to the diction of the characters, with those closest to the narrator having the best character, and in this reading Mr. Knightley has the best character.[115] A. Walton Ktiz argued that the aspect of the novel of "Knightley as the standard" prevents the irony of Emma from becoming a cynical celebration of feminine manipulation, writing that Austen's use of free indirect discourse allowed the reader to understand Emma mind without becoming limited by it.[116]

Another major theme of Austen scholarship has concerned the question of the Bildungsroman (novel of education).[117] D. D. Devlin in Jane Austen and Education (1975) argued that Austen's novels were all in varying ways Bildungsroman, where Austen put into practice Enlightenment theories about how the character of young people can develop and change.[117] The Italian literary critic Franco Moretti in his 1987 book The Way of the World called Pride and Prejudice a "classic" Bildungsroman, where Elizabeth Bennet's "prejudice" against Mr. Darcy is really "distrust" and that "she does not err due to a lack of criticism, but due to an excess, as Bennet rejects anything that she is told to trust a priori.[118] Moretti argued that a typical Bildungsroman of the early 19th century was concerned with "everyday life", which represented "an unchallenged stability of social relationships" in a world that was wracked by war and revolution.[118] In this sense, Moretti argued that the education that Bennet needs is to learn to accept the stability represented by the world around her in England, which is preferable to war and revolution to be found elsewhere in Europe, without losing her individualism.[118] In the same way, Clifford Siskin in his 1988 book The Historicity of Romantic Discourse argued that all of Austen's books were Bildungsroman, where the struggle of the characters to develop was mainly "internal" as the challenge to the characters was not really to change their onward lives, but rather their "self".[118] Siskin noted in Henry Fielding's popular 1742 novel Joseph Andrews, that a young man working as humble servant, goes through much suffering, and is ultimately rewarded when it is discovered that he is really an aristocrat kidnapped by the Romany (gypsies) when he was a baby.[119] By contrast, Siskin wrote that Elizabeth Bennet's paternity is not in question and there are not improbable strokes of luck which will make her rich; instead her struggle is to develop her character and conquer her "prejudice" against Darcy, marking the shift in British literature from an "external" to "internal" conflict.[119] Alongside studies of Austen as the writer of Bildungsroman are studies of Austen as a writer of marriage stories.[120] For Susan Fraiman, Pride and Prejudice is both a Bildungsroman concerning Elizabeth Bennet's growth and a marriage story that ends in her "humiliation" where she ends up submitting to Mr. Darcy.[121] Critics are badly divided over the question of whether the marriages of Austen's heroines are meant to be a reward for their virtuous behavior as seen by Wayne Booth, or merely "Good Girl Being Taught a Lesson" stories as seen by Claudia Johnson.[121] Stuart Tave wrote that Austen's stories always seem to end unhappily, but then end with the heroine getting married happily, which led him to the conclusion that these happy endings were artificial endings imposed by the expectations of an early 19th century audience.[121]

About the question of the "relevance" of Austen to the modern world, Julia Prewitt Brown in her 1979 book Jane Austen's Novels: Social Change and Literary Form challenged the common complaint that she did not deal with social changes, by examining how she presented social changes within the households she chronicled.[122] Brown argued that the social changes Austen examined were the birth of the "modern" individualism where people were "alienated" from any meaningful social identity, existing only as "atoms" in society.[122] The exhibit A of her thesis, so to speak, was Persuasion where she argued that Anne Eliot cannot find personal happiness by marrying within the gentry; only marriage to the self-made man Captain Wentworth can give her happiness.[122] Brown argued that Persuasion was in many ways the darkest of Austen's novels, depicting a society in grip of moral decay, where the old hierarchical certainties had given way to a society of "disparate parts", leaving Eliot as a "disoriented, isolated" woman.[122] Brown was not a Marxist, but her book owed much to the Hungarian Communist writer Georg Lukács, especially his 1920 book The Theory of the Novel.[122]

One of the most fruitful and contentious arguments has been the consideration of Austen as a political writer. As critic Gary Kelly explains, "Some see her as a political 'conservative' because she seems to defend the established social order. Others see her as sympathetic to 'radical' politics that challenged the established order, especially in the form of patriarchy ... some critics see Austen's novels as neither conservative nor subversive, but complex, criticizing aspects of the social order but supporting stability and an open class hierarchy."[123] In Jane Austen and the War of Ideas (1975), perhaps the most important of these works, Marilyn Butler argues that Austen was steeped in, not insulated from, the principal moral and political controversies of her time, and espoused a partisan, fundamentally conservative and Christian position in these controversies. In a similar vein, Alistair M. Duckworth in The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels (1971) argues that Austen used the concept of the "estate" to symbolise all that was important about contemporary English society, which should be conserved, improved, and passed down to future generations.[124] Duckworth argued that Austen followed Edmund Burke, who in his 1790 book Reflections on the Revolution in France had used the metaphor of an estate that represented the work of generations, and which could be only be improved, never altered, for the way that society ought to work.[125] Duckworth noted that in Austen's books, one's ability to keep an estate going, which could only be improved, but never altered if one was to be true to the estate, is usually the measure of one's good character.[126] Butler placed Austen in the context of the reaction against the French Revolution, where excessive emotionalism and the sentimental "cult of sensibility" came to be identified with sexual promiscuity, atheism, and political radicalism.[127] Butler argued that a novel like Sense and Sensibility, where Marianne Dashwood is unable to control her emotions, is part of the conservative anti-revolutionary literature that sought to glorify old fashioned values and politics.[127] Irvine pointed out that the identification of the "cult of sensibility" with republicanism was one that existed only in the minds of conservatives, and in fact the French Republic also rejected sentimentalism, so Butler's challenge is to prove Austen's call for emotional self-restraint as expressed by a character like Elinor Dashwood is in fact grounded in conservative politics.[127] Butler wrote "the characteristic recourse of the conservative ... is to remind us ultimately of the insignificance of individual rights and even individual concerns when measured against the scale of 'the universe as one vast whole'".[128] Irvine wrote that a novel like Sense and Sensibility appears to support Butler's thesis, but a novel like Pride and Prejudice does not, as Elizabeth Bennet is an individualist and a non-conformist who ridicules everything, and who to a certain extent has to learn the value of sentiment.[129]

Regarding Austen's views of society and economics, Alastair MacIntyre in his 1981 After Virtue offered a critique of the Enlightenment as leading to moral chaos and decay, and citing Aristotle argued that a "good life for man" is only possible if one follows the traditional moral rules of one's society.[130] In this regard, MacIntyre used Austen as an "Aristotelian" writer whose books offered up examples of how to be virtuous, with the English country estate playing the same role that the polis did for Aristotle.[130] By contrast, Mary Evans in her 1987 book Jane Austen and the State depicted Austen as a proto-Marxist concerned with the "stability of human relationships and communities" and against "conspicuous consumption" and the "individualisation of feeling" promoted by the Industrial Revolution.[131] In her 1987 book Desire and Domestic Fiction, Nancy Armstrong, in a study much influenced by the theories of Karl Marx and Michel Foucault, argued that all of Austen's books reflected the dominant political-economic ideology of her times, concerning the battle to exercise power over the human body, which determined how and whether a woman was considered sexually desirable or not.[132] The Marxist James Thompson in his 1988 book Between Self and the World likewise depicted Austen as a proto-Marxist searching for a realm of freedom and feeling in a world dominated by a soulless materialism promoted by capitalism.[131] By contrast, Beth Fowkes Tobin in her 1990 article "The Moral and Political Economy of Austen's Emma" depicted Austen as a Burkean conservative with Mr. Knightly as a responsible land-owner taking care of his family's ancient estate and Emma Woodhouse symbolising wealth cut off from any sort of social role.[133] David Kaufmann in his 1992 essay "Propriety and the Law" argued that Austen was a classical liberal in the mold of Adam Smith, who felt that virtue was best exercised in the private sphere of the family life rather than in the public sphere of politics.[134] Kaufmann rejected the claim that Austen was influenced by Edmund Burke, arguing that for Austen, virtue was not something passed down from time immemorial from a landed elite as Burke would have it, but rather was something that any individual could acquire, thus making Austen into something of a radical.[134] Lauren Goodlad in a 2000 article rejected Kaufmann's claim of Austen as a classical liberal, arguing that the message of Sense and Sensibility was the failure of liberalism to reconcile alienated individuals from a society that only valued money.[135] As Rajeswari Rajan notes in her essay on recent Austen scholarship, "the idea of a political Austen is no longer seriously challenged". The questions scholars now investigate involve: "the [French] Revolution, war, nationalism, empire, class, 'improvement' [of the estate], the clergy, town versus country, abolition, the professions, female emancipation; whether her politics were Tory, Whig, or radical; whether she was a conservative or a revolutionary, or occupied a reformist position between these extremes".[136]

[I]n all her novels Austen examines the female powerlessness that underlies monetary pressure to marry, the injustice of inheritance laws, the ignorance of women denied formal education, the psychological vulnerability of the heiress or widow, the exploited dependency of the spinster, the boredom of the lady provided with no vocation.

– Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic (1979)[137]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Austen studies was influenced by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's seminal The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), which contrasts the "decorous surfaces" with the "explosive anger" of 19th-century female English writers. This work, along with other feminist criticism of Austen, has firmly positioned Austen as a woman writer. Gibler and Gubar suggested that what are usually seen as the unpleasant female characters in the Austen books like Mrs. Norris in Mansfield Park, Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Pride and Prejudice and Mrs. Churchill in Emma were in fact expressions of Austen's anger at a patriarchal society, who are punished in guilt over her own immodesty in writing novels, while her heroines who end up happily married are expressions of Austen's desire to compromise with society.[138] The Gilbert-Gubar thesis proved to be influential and inspired scholars to reexamine Austen's writings, though most have a more favorable opinion of her heroines than Gilbert and Gubar did.[139] Other scholars such as Linda Hunt have argued that Austen used realism as a way of attacking patriarchy from the outside as opposed to subverting it from within by irony as Gilbert and Gubar claimed.[139] The interest generated in Austen by these critics led to the discovery and study of other woman writers of the time.[140] Moreover, with the publication of Julia Prewitt Brown's Jane Austen's Novels: Social Change and Literary Form (1979), Margaret Kirkham's Jane Austen: Feminism and Fiction (1983), and Claudia L. Johnson's Jane Austen: Women, Politics and the Novel (1988), scholars were no longer able to easily argue that Austen was "apolitical, or even unqualifiedly 'conservative'".[141] Kirkham, for example, described the similarities between Austen's thought and that of Mary Wollstonecraft, labelling them both as "Enlightenment feminists". Kirham argued that by showing that women were just as capable of being rational as men, that Austen was a follower of Wollstonecraft.[142] Johnson similarly places Austen in an 18th-century political tradition, although she outlines the debt Austen owes to the political novels of the 1790s written by women.[143]

The war with France that began in 1793 was seen as an ideological war between the British monarchy vs. the French republic, which led conservative writers such as Jane West, Hannah More, and Elizabeth Hamilton to depict the feminine private sphere in the family as the embodiment of British values under threat from France, and to write a series of polemical works demanding that young women defend their "modesty", as defined by conduct books, to give Britain the moral strength to prevail over the French.[144] Johnson argued that Austen appropriated the sort of plot that More, West and Hamilton used in their books to quietly subvert via irony.[145] In support of her thesis, Johnson noted in Sense and Sensibility that the Dashwood sisters are victimized by their greedy half-brother John, showing the family as an area for competition instead of warmth and comfort; in Mansfield Park the lifestyle of the eminently respectable Bertram family is supported by a plantation in Antigua worked by slave labour; and Northanger Abbey where satirizing Gothic stories gives "a nightmare version of patriarchal oppression" as General Tilney, if not guilty of the specific crimes that Catherine Moreland imagines he has committed, is indeed a vicious man.[146] Likewise, Johnson noted that Maria Rushworth's adultery in Mansfield Park is portrayed as merely salacious local gossip that does not presage a great victory for Napoleon while Marianne Dashwood does not die after being seduced by Willoughby, which undercuts the standard plot devices of the conservative writers.[147] Johnston argued because of the drastic wartime censorship and the campaign of vitriolic abuse waged against Wollstonecraft that Austen had to be quiet in their criticism of patriarchy.[148] Irvine, in a critique of the work of feminist scholars like Johnson and Kirkham, argued that if Austen was indeed an Enlightenment feminist, there were clearly limits to her radicalism as Austen never criticised either explicitly or implicitly the hierarchical structure of British society, with her villains failing to live up to the standards expected of their class, instead of their moral failures being presented as a product of the social system.[149] Writing about the work of Johnson, Irvine wrote that for her, Austen was a radical because it is women like Emma Woodhouse, Mrs. Elton and Mrs. Churchill who really run Highbury society, undercutting traditional gender roles, but Irvine questioned whether this really made Austen into radical, noting it was the wealth and status of the gentry women of Highbury that gave them their power.[150] Irvine argued it was just as possible to see Emma as a conservative novel that upholds the superiority of the gentry, writing that Johnson was "close here to defining 'conservative' in terms of gender politics alone".[150] Likewise, Elizabeth may defy Lady Catherine de Bourgh who wants to keep her in place by marrying Mr. Darcy, who comes from old landed family, which Irivine used to argue that while Pride and Prejudice does have a strong heroine, the book does not criticise the structure of English society.[151]

Many scholars have noted "modesty" in the "conduct books" that were very popular for setting out the proper rules for young ladies. In Austen's book there was a double meaning to the word modesty.[152] Modesty meant that a woman should refrain from flamboyant behavior and be quiet; modesty also meant that a woman had to be ignorant of her sexuality.[152] This double meaning meant that a young woman who was behaving in a modest way was not really modest at all as she was attempting to conceal her knowledge of her sexuality, placing young women in an impossible position.[152] Jan Fergus argued that for this reason, Austen's books were subversive, engaging in "emotional didacticism" by showing the reader moral lessons meant to teach young women how to be modest in the conventional sense, thus undercutting the demand made by the conduct books for modesty in the sense of ignorance of one's sexuality.[153] In the same way, Kirkham used Mansfield Park as an example of Austen undercutting the message of the conduct books, noting that Fanny Price is attractive to Henry Crawford because she outwardly conforms to the conduct books, while, at the same time, rejecting the enfantisisation of women promoted by the conduct books, she is attractive to Edmund Bertram because of her intelligence and spirit.[154] Rachel Brownstein argued that Austen's use of irony should be seen in the same way, as a way of writing in a manner expected of a woman writer in her age while, at the same time, undercutting such expectations.[153] Devoney Looser in the 1995 book Jane Austen and the Discourses of Feminism argued in her introduction that there were a number of ways in which Austen could be placed, not merely within a feminist tradition, but as herself a feminist.[153]

Using the theories of Michel Foucault as their guide, Casey Finch and Peter Bowen in their 1990 essay, "'The Tittle-Tattle of Highbury': Gossip and the Free Indirect Style in Emma", argued that the free indirect discourse in Austen validates Foucault's thesis that the Enlightenment was a fraud, an insidious form of oppression posing as liberation.[155] Finch and Bowen argued that the voice of the omnipresent narrator, together with the free indirect discourse summarizing the thoughts of characters in Emma, were a form of "surveillance" that policed the thoughts of the character. Seen in this light, Emma Woodhouse's discovery that she loves Mr. Knightley is not an expression of her real feelings, but rather society imposing its values on her mind, persuading her that she had to engage in a heterosexual marriage to produce sons to continue the Establishment, all the while fooling her into thinking she was in love.[156] By contrast, Lauren Goodlad in her 2000 essay "Self-Disciplinary Self-Making" argued that the self-discipline exercised by Elinor Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility was not an act of oppression as held by Foucault and those writing from a Foucaultian perspective, but was an "emancipatory act of political resistance", arguing that there was a tension between "psychology" and "character" since Dashwood must be the observer of her character, and used what she has learned to grow.[157]

A very controversial article was "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick that juxtaposed three treatments of female suffering, namely Marianne Dashwood's emotional frenzy when Willoughby abandons her, a 19th century medical account of the "cure" inflicted on a girl who liked to masturbate, and the critic Tony Tanner's "vengeful" treatment of Emma Woodhouse as a woman who had to be taught her place.[158] Sedgwick argued that the way the portrayal of Marianne as emotionally overwrought and too inclined to give in to her feelings very closely resembled the account of patient X, the teenage girl seen as too inclined to masturbate, and the way a male critic like Tanner attacked Woodhouse for her emotional self-indulgence was no different from the doctor imposing the gruesome and painful treatment on the masturbating girl.[159] Sedgwick says that the way Elinor disciplines Marianne, Tanner's "vengeful" views and the treatment given to patient X were all attempts to crush female sexuality as she maintained that "emotional self-indulgence" was merely a code-word for female masturbation.[159] Sedgwick argued that characters such as Dashwood and Woodhouse, who did not precisely conform to the feminine ideals are symbols of both female and homosexual resistance to the ideal of heterosexuality and patriarchy as the norm for everyone.[160] Sedgwick's provoked an uproar in 1991, becoming a prime exhibit in the American "culture war" between liberals and conservatives.[160]

The Italian critic Franco Moretti argued that Austen's novels articulated a new form of English nationalism via the marriage plot, noting most of the heroes and heroines came from different parts of England.[161] Some critics such as Roger Gard have seized upon Austen as a symbol of an "eternal England", whose "unpolitical" works unlike the "political" novels of the great French and Russian novelists of the 19th century reflected the central values of "modern Anglo-Saxon civilisations".[162] According to Gard, Austen is so English that only the English could really appreciate Austen, writing "Foreigners, whether reading in translation or in the original, see little or nothing of her true brilliance ... the feel of Jane Austen-so far as we can imagine it dissociated from her language is still ... peculiarly English".[163] Irvine wrote that Gard's book 1992 Jane Austen's Novels: The Art of Clarity is full of historical errors such as his claim that Austen was part of the movement towards "an evolving national democracy", when in fact the Great Reform Bill, which lowered the franchise requirements for men in a very limited way, was passed in 1832, 15 years after Austen's death, and "nowhere in her novels or letters is England imagined as 'evolving' towards democracy of any kind".[164] Irvine wrote that while Austen did see England as different from the rest of Europe, she did not see England as apart from Europe in the way that Gard claimed, or as a part of "Anglo-Saxon civilisations", which apparently include the United States and English-speaking parts of the Commonwealth, a way of thinking that did not exist in her time.[164] Irvine charged that Gard appeared to be trying to use Austen as a way of furthering his opposition to British membership in the European Union, with his dichotomy between Austen's England with its "clear" style and "unpolitical" way of life vs. the presumably muddled style and "political" way of life of continental Europe with the implication that the two do not belong together.[164]

In the late-1980s, 1990s and 2000s ideological, postcolonial and Marxist criticism dominated Austen studies.[165] Generating heated debate, Edward Said devoted a chapter of his book Culture and Imperialism (1993) to Mansfield Park, arguing that the peripheral position of "Antigua" and the issue of slavery demonstrated that acceptance of colonialism was an unspoken assumption in Austen's society during the early 19th century. The question of whether Mansfield Park justifies or condemns slavery has become heated in Austen scholarship, and Said's claims have proved to be highly controversial.[166] The debate about Mansfield Park and slavery is the one issue in Austen scholarship that has transcended the limits of academia to attract widespread public attention.[167] Many of Austen's critics come from the field of post-colonial studies, and take up Said's thesis about Mansfield Park reflecting the "spatial" understanding of the world that he argued was used to justify overseas expansion.[168] Writing in a post-colonial vein, Carl Plasa in his 2001 essay "'What Was Done There Is Not To Be Told' Mansfield Park's Colonial Unconscious" argued that the "barbarism" of Maria Bertram's sexuality, which leads her into adultery, is a metaphor for the "barbarism" of the Haitian Revolution, which attracted much media attention in Europe at the time, and was often presented as due to the "barbarism" and uncontrolled sexuality of the Haitian slaves.[169] Plasa argued that society in Austen's time was based on a set of expectations about everyone being in their "place", which created order. The Haitian Revolution was seen as a symbol of what happened to a society without order, and Plasa argued that it was not accident that when Sir Thomas Bertram leaves Mansfield Park for his plantation in Antigua that his family falls apart, showing the importance of the family and individuals staying in their proper "place".[169] Likewise, Maaja Stewart in her 1993 book Domestic Realities and Imperial Fictions argued that the plantations in the Caribbean were the source of much worry about female sexuality in Austen's time, with the main concerns being the need of slave owners to depend upon the fertility of slave women to create more slaves when the slave trade was abolished in 1807, and about the general collapse of traditional European morality in the West Indies as the slave masters routinely kept harems of slave women or alternatively, raped female slaves.[169] Stewart linked these concerns to Mansfield Park, writing that Sir Thomas Bertram's failure to manage his own family is put down to his failure to manage the emerging sexuality of his teenage daughters, which is precisely the same charge that was applied to the owners of the plantations in the West Indies at the same time.[169]

Other critics have seen the message of Mansfield Park as abolitionist.[169] Joseph Lew argued that Fanny's refusal to marry Henry Crawford was "an act of rebellion, endangering a system based upon the exchange of women between men as surely as a slave's refusal to work".[169] Susan Fraiman, in a 1995 essay argued strongly against the Said thesis, arguing that the values of Sir Thomas are those which Austen affirms in Mansfield Park and that if his attempt to restore order to his family in Mansfield Park is seen as analogous to his restoration of order at his Antigua plantation, then he was a failure for the "moral blight" at Mansfield Park that he finds after he returns to England.[169] Fraiman conceded to Said that Austen was one of the writers who "made colonialism thinkable by constructing the West as center, home and norm", but argued slavery in Mansfield Park "is not a subtext wherein Austen and Sir Thomas converge", but rather is used by Austen "to argue the essential depravity of Sir Thomas's relations to other people".[169] Fraiman argued that Austen used the issue of slavery to argue against the patriarchal power of an English gentleman over his family, his estate and "by implication overseas".[169] Fraiman argued that imperial discourse from the era tended to depict the empire as masculine and the colonies as feminine, which led to the conclusion that Said had merely inverted this discourse by making Austen a representative of empire while lionizing various male anti-colonial writers from the colonies.[170] Brian Southam in a 1995 essay argued that the much discussed scene about the "dead silence" that follows Fanny Price's questions about the status of slaves in the Caribbean refers to the moral decadence of those members of the British gentry who chose to be involved in the abolitionist campaigns of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[170] Trevor Lloyd in a 1999 article argued on the basis of the statements in the novel, that about 10% of the income from Mansfield Park came from the plantation in Antigua.[171] John Wiltshire in a 2003 article argued that the parallel between the condition of women and the treatment of slaves in the West Indies is to be understood as metaphoric, not as literal, and that Sir Thomas' willingness to make a trip in the middle of a war to his plantation in Antigua, despite the well known perils of yellow fever and malaria in the Caribbean, suggested that he be understood as a good master.[171] In Wiltshire's account, it is the slave trade, not slavery, that Austen condemns in Mansfield Park.[171]

Irvine argued that though all of Austen's novels are set in provincial England, there is in fact a global component to her stories with the British Empire being portrayed as a place where men go off on adventures, become wealthy and to tell stories which edify the heroines.[172] Irvine used as examples the naval career of Captain Wentworth in Persuasion; that Sir Thomas Bertram owes a plantation in Antigua while William Price enlists in the Royal Navy in Mansfield Park; and Colonel Brandon is a veteran of military campaigns in the West Indies in Sense and Sensibility.[172] Irvine observed that all of these men are in some way improved by the love of women, who domesticate otherwise scarred men, writing that "the profits of the modern military/mercantile empire can only be put to use in renovating Britain's social order through the figure of the domestic woman", who do this by "listening to the stories that male adventurers can tell."[172] Irvine argued that Elinor Dashwood, by arranging for Colonel Brandon to marry her sister Marianne, is finding for him the "home" he lost from experiencing both emotional and physical turmoil while serving in the West Indies. [172] Irvine suggested that for Austen, women had a role in domesticating men scarred by their overseas experiences, and that Said was wrong that Austen could "not" write about empire; arguing instead in Austen's works that the "stories of empire" are placed in a "context of their telling that domesticates them, removes them from the political and moral realm where the horrors they describe might demand a moral and political response".[172]

Another theme of recent Austen scholarship concerns her relationship with British/English national identity within the context of the long wars with France.[173] Jon Mee in his 2000 essay "Austen's Treacherous Ivory: Female Patriotism, Domestic Ideology, and Empire" examined how Fanny Price defined her sense of Englishness in connection with the English countryside, arguing that Austen was presenting a version of England defined as country estates in a bucolic countryside that was insulated from a "larger, more uncertain and un-English world".[173] Mee suggested that in Emma, the very name of Mr. Knightley, which suggests the Middle Ages, together with the name of his estate, Donwell Abbey, are meant to suggest a continuity between medieval and modern England, in contrast to the newness of the political institutions in the novice republics in the United States and France.[173] Miranda Burgress in her 2000 book British Fiction and the Production of Social Order argued that Austen defined her England as a nation made up of readers, as the experience of reading the same books had created a common culture across all of England.[174] In this regard, Janet Sorenson in The Grammar of Empire noted that in Austen's books, no characters speak in dialect, and all use the same form of polite "King's English" that was expected of the upper classes.[175]

In Jane Austen and the Body: 'The Picture of Health', (1992) John Wiltshire explored the preoccupation with illness and health of Austen's characters. Wiltshire addressed current theories of "the body as sexuality", and more broadly how culture is "inscribed" on the representation of the body.[176] There has also been a return to considerations of aesthetics with D. A. Miller's Jane Austen, or The Secret of Style (2003), which connects artistic concerns with queer theory.[177] Miller in his book began the "queer" reading of Austen, when he asked why Austen's work which celebrates heterosexual love is so popular with gay men.[159] Miller answered that it was because the narrator of the novels has no sexuality and has a "dazzling verbal style", which allows homosexuals to identity with the narrator who stands outside the world of heterosexuality and whose chief attribute is a sense of style.[178]

Modern popular culture

Modern Janeites

Critic Claudia Johnson defines "Janeitism" as "the self-consciously idolatrous enthusiasm for 'Jane' and every detail relative to her".[41] Janeites not only read the novels of Austen; they also re-enact them, write plays based on them, and become experts on early 19th-century England and its customs.[180] Austen scholar Deidre Lynch has commented that "cult" is an apt term for committed Janeites. She compares the practices of religious pilgrims with those of Janeites, who travel to places associated with Austen's life, her novels and the film adaptations. She speculates that this is "a kind of time-travel to the past" which, by catering to Janeites, preserves a "vanished Englishness or set of 'traditional' values".[181] The disconnection between the popular appreciation of Austen and the academic appreciation of Austen that began with Lascelles has since widened considerably. Johnson compares Janeites to Trekkies, arguing that both "are derided and marginalized by dominant cultural institutions bent on legitimizing their own objects and protocols of expertise". However, she notes that Austen's works are now considered to be part of both high culture and popular culture, while Star Trek can only claim to be a part of popular culture.[182]

Adaptations

Sequels, prequels and adaptations based on Austen's work range from attempts to enlarge on the stories in Austen's own style to the soft-core pornographic novel Virtues and Vices (1981) and fantasy novel Resolve and Resistance (1996). Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, Austen family members published conclusions to her incomplete novels. By 2000 there were over 100 printed adaptations of Austen's works.[183] According to Lynch, "her works appear to have proven more hospitable to sequelisation than those of almost any other novelist".[184] Relying on the categories laid out by Betty A. Schellenberg and Paul Budra, Lynch describes two different kinds of Austen sequels: those that continue the story and those that return to "the world of Jane Austen".[185] The texts that continue the story are "generally regarded as dubious enterprises, as reviews attest" and "often feel like throwbacks to the Gothic and sentimental novels that Austen loved to burlesque".[186] Those that emphasise nostalgia are "defined not only by retrograde longing but also by a kind of postmodern playfulness and predilection for insider joking", relying on the reader to see the web of Austenian allusions.[187]

Between 1900 and 1975, over 60 radio, television, film and stage productions appeared.[188] The first feature-film adaptation was the 1940 MGM production of Pride and Prejudice starring Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson. It has long been said that a Hollywood adaptation was first suggested by the entertainer Harpo Marx, who had seen a dramatisation of the novel in Philadelphia in 1935, but the story is of doubtful accuracy.[189] Directed by Robert Z. Leonard and written in collaboration with the English novelist Aldous Huxley and American screenwriter Jane Murfin, the film was critically well-received, although the plot and characterisations strayed from Austen's original.[190] Filmed in a studio and in black and white, the story's setting was relocated to the 1830s with opulent costume designs.[191]

In direct opposition to the Hollywood adaptations of Austen's novels, BBC dramatisations from the 1970s onward aimed to adhere meticulously to Austen's plots, characterisations, and settings.[192] The 1972 BBC adaptation of Emma, for example, took great care to be historically accurate, but its slow pacing and long takes contrasted unfavourably to the pace of commercial films.[191] The BBC's 1980 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice adopted many film techniques—such as the use of long landscape shots—that gave the production a greater visual sophistication. Often seen as the start of the "heritage drama" movement, this production was the first to be filmed largely on location.[193] A push for "fusion" adaptations, or films that combined Hollywood style and British heritage style, began in the mid-1980s. The BBC's first fusion adaptation was the 1986 production of Northanger Abbey, which combined authentic style and 1980s punk, with characters often veering into the surreal.[194]

A wave of Austen adaptations began to appear around 1995, starting with Emma Thompson's adaptation of Sense and Sensibility for Columbia Pictures, a fusion production directed by Ang Lee.[194] This star-studded film departed from the novel in many ways, but it became a commercial and critical success, and was nominated for numerous awards, including seven Oscars. The BBC produced two adaptations in 1995: Persuasion and Andrew Davies's six-episode television drama, Pride and Prejudice. Starring Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle, Davies's production ignited "Darcymania" in Britain. Critics praised its smart departures from the novel as well as its sensual costuming, fast-paced editing, and original yet appropriate dialogue.[195] The series sparked an explosion in the publication of printed Austen adaptations; in addition, 200,000 video copies of the serial were sold within a year of its airing, 50,000 within the first week alone.[188] Another adaptation of Pride and Prejudice was released in 2005. Starring Keira Knightley, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet, Joe Wright's film marked the first feature adaptation since 1940 that aspired to be faithful to the novel.[196] Three more film adaptations appeared in 2007—Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.[197] Love & Friendship, a film version of Austen's early epistolary novel Lady Susan, was released in 2016. Directed by Whit Stillman and starring Kate Beckinsale and Chloë Sevigny, the film's title was taken from one of Austen's juvenile writings.[198]

Books and scripts that use the general story line of Austen's novels but change or otherwise modernize the story also became popular at the end of the 20th century. Clueless (1995), Amy Heckerling's updated version of Emma that takes place in Beverly Hills, became a cultural phenomenon and spawned its own television series.[199] Bridget Jones's Diary (2001), based on the successful 1996 book of the same name by Helen Fielding, was inspired by both Pride and Prejudice and the 1995 BBC adaptation.[200] The Bollywoodesque production Bride and Prejudice, which sets Austen's story in present-day India while including original musical numbers, premiered in 2004.[201]

See also

- Books in the United Kingdom

Notes

- Clark, Robert. "Jane Austen". The Literary Encyclopedia (subscription only). 8 January 2001. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- Looser, Devoney. The Making of Jane Austen. 19–22.

- Looser, Devoney. The Making of Jane Austen. 83–97.

-

"100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- Lascelles, 2.

- Lascelles, 4–5; MacDonagh, 110–28; Honan, Jane Austen, 79, 183–85; Tomalin, 66–68.

- Le Faye, Family Record, 100, 114.

- Le Faye, Family Record, 104.

- Fergus, 13–14.

- Le Faye, Family Record, 225.

- Qtd. in Le Faye, Family Record, 226; also see Jane Austen to J. S. Clarke, 11 December 1815, courtesy of janeausten.co.uk, 17 July 2011.

- Le Faye, Family Record, 227.

- Le Faye, "Memoirs and biographies", 51.

- Qtd. in Fergus, 12.

- Fergus, 12–13.

- Southam, "Criticism, 1870–1940", 102.

- Litz, Jane Austen, 3–14; Grundy, 192–93; Waldron, 83, 89–90; Duffy, 93–94.

- Gilbert and Gubar, 151.

- Litz, Jane Austen, 142.

- MacDonagh, 66–75.

- Honan, 124–27; Trott, 92.

- Southam, "Introduction", Vol. 1, 7.

- Honan, Jane Austen, 289–90; emphasis in original.

- Honan, Jane Austen, 318.

- Honan, Jane Austen, 318–19; emphasis in original.

- Honan, Jane Austen, 347.

- Fergus, 18.

- Fergus, 18–19; Honan, Jane Austen, 287–89, 316–17, 372–73; Southam, "Introduction", Vol. 1, 1.

- Waldron, 83–91.

- Southam, Vol. 1, 6.

- Scott, 58; see also Litz, "Criticism, 1939–1983", 110; Waldron, 85–86; Duffy, 94–96.

- Galperin, 96.

- Southam, "Scott on Jane Austen", Vol. 1, 106; Scott, 155.

- Waldron, 89.

- Waldron, 84–85, 87–88.

- Waldron, 89–90; Duffy, 97; Watt, 4–5.

- Southam, "Whately on Jane Austen", Vol. 1, 100–01.

- Watt, 2.

- Duffy, 98–99; see also MacDonagh, 146; Watt, 3–4.

- Southam, "Introduction", Vol. 1, 2; Southam, "Introduction", Vol. 2, 1.

- Johnson, 211.

- Southam, "Introduction", Vol. 1, 20.

- Duffy, 98–99.