Responsibility for the Holocaust

Responsibility for the Holocaust is the subject of an ongoing historical debate that has spanned several decades. The debate about the origins of the Holocaust is known as functionalism versus intentionalism. Intentionalists such as Lucy Dawidowicz argue that Adolf Hitler planned the extermination of the Jewish people as early as 1918, and personally oversaw its execution. However, functionalists such as Raul Hilberg argue that the extermination plans evolved in stages, as a result of initiatives that were taken by bureaucrats in response to other policy failures. To a large degree, the debate has been settled by acknowledgement of both centralized planning and decentralized attitudes and choices.

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

The primary responsibility for the Holocaust rests on Hitler and the Nazi Party leadership, but operations to persecute Jews, Romani people, homosexuals and others were also perpetrated by the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Wehrmacht, and ordinary German citizens as well as by collaborationist members of various European governments, including their soldiers and civilians. A host of factors contributed to the environment in which atrocities were committed across the continent, ranging from general racism (including antisemitism), religious hatred, blind obedience, apathy, political opportunism, coercion, profiteering, and xenophobia.

Historical and philosophical interpretations

The enormity of the Holocaust has prompted much analysis. The Holocaust has been characterized as a project of industrial extermination.[1] This led authors such as Enzo Traverso to argue in The Origins of Nazi Violence that Auschwitz was explicitly a product of Western civilization originating from medieval religious and racial persecution that brought together a "particular kind of stigmatization...rethought in the light of colonial wars and genocides."[2][lower-alpha 1] Beginning his book with a description of the guillotine, which according to him marks the entry of the Industrial Revolution into capital punishment, he writes: "Through an irony of history, the theories of Frederick Taylor" (taylorism) were applied by a totalitarian system to serve "not production, but extermination."[3][lower-alpha 2]

Others like Russell Jacoby contend that the Holocaust is a product of German history with deep roots in German society ranging from, "German authoritarianism, feeble liberalism, brash nationalism or virulent antisemitism. From A. J. P. Taylor's The Course of German History fifty-five years ago to Daniel Goldhagen's controversial work, Hitler's Willing Executioners, Nazism is understood as the outcome of a long history of uniquely German traits".[4] While some claim that the specificity of the Holocaust was also rooted in the constant antisemitism from which Jews had been the target since the foundation of Christianity, intellectual historian George Mosse argued that the extreme form of European racism that led to the Holocaust fully emerged in the eighteenth century.[5] Others argue that pseudo-scientific racist theories were elaborated upon in order to justify white supremacy and that they were accompanied by the Darwinian belief in the survival of the fittest and eugenic notions of racial hygiene—particularly within the German scientific community.[6][lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4]

Authorization

The question of overall responsibility for the atrocities committed under the Nazi regime traverses the oligarchy of those in command, foremost among them Adolf Hitler. In October 1939, he authorized the first Nazi mass killing for those labeled "undesirables" in the T-4 Euthanasia Program.[7][8] The Nazis termed such people as being "Lives unworthy of life." or lebensunwertes Leben in German.[9] Before the euthanasia program in Germany-proper was over, the Nazis killed between 65,000–70,000 persons.[10] Historian Henry Friedlander calls this period during which the 70,000 adults were killed, the "first phase" of the T4 Program since the program and its contributors precipitated the Holocaust.[11] Sometime between late June 1940 when planning for Operation Barbarossa first started and March 1941, orders were approved by Hitler for the re-establishment of the Einsatzgruppen (the surviving historical record does not permit firm conclusions to be drawn about the precise date).[12] Hitler encouraged the killings of the Jews of Eastern Europe by the Einsatzgruppen death squads in a speech of July 1941.[13] Evidence suggests that in the fall of 1941, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and Hitler agreed in principle on the complete mass extermination of the Jews of Europe by gassing, with Hitler explicitly ordering the "annihilation of the Jews" in a speech on 12 December 1941, by which time the Jewish populations in the Baltic states had been effectively eliminated.[14] To make for smoother intra-governmental cooperation in the implementation of this so-called "Final Solution to the Jewish Question", the Wannsee conference was held near Berlin on 20 January 1942, with the participation of fifteen senior officials, led by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann; the records of which provide the best evidence of the central planning of the Holocaust. Just five weeks later on 22 February, Hitler was recorded saying to his closest associates: "We shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jew."[15]

Allied knowledge of the atrocities

Upwards of 300 Jewish organizations attempted to provide information to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt about the persecution of Jews in Europe, but the ethnic and cultural diversity of American immigrant Jewish communities and their comparative lack of political power in the U.S. hindered their ability to influence policy.[16] Various strategies, such as ransoming Jews following the Anschluss of 1938, failed for a host of reasons, not to exclude the unwillingness and inability of Jewish communities in the U.S. to extend financial aid to their suffering brethren.[17] Clear evidence exists that Winston Churchill was privy to intelligence reports derived from decoded German transmissions in August 1941, during which he stated:

Whole districts are being exterminated. Scores of thousands – literally scores of thousands – of executions in cold blood are being perpetrated by the German police-troops upon the Russian patriots who defend their native soil. Since the Mongol invasions of Europe in the sixteenth century, there has never been methodical, merciless butchery on such a scale, or approaching such a scale.

During the early years of the war, the Polish government-in-exile published documents and organised meetings to spread the word about the fate of Jews (see Witold Pilecki's Report). In the summer of 1942, a Jewish labor organization (the Bund) leader, Leon Feiner got word to London that 700,000 Polish Jews had already been murdered. The Daily Telegraph published it on 25 June 1942,[19] and the BBC took the story seriously, though the U.S. State Department doubted it.[20]

On 10 August 1942, the Riegner Telegram to New York described the Nazi plan to murder all the Jews in the occupied states by deporting them to concentration camps in the east, to be exterminated in one blow, possibly by prussic acid, starting at autumn 1942. It was released in the United States by Stephen Wise of the World Jewish Congress in November 1942 after a long wait for permission from the government.[21] This led to attempts by Jewish organizations to put President Roosevelt under pressure to act on behalf of the European Jews, many of whom had tried in vain to enter either Britain or the U.S.[22]

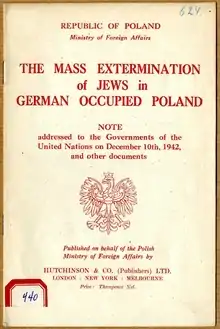

Reports were also coming into Palestine about the German atrocities during the autumn of 1942.[23] The allies received a detailed eyewitness account from Polish resistance fighter and later Georgetown University professor, Jan Karski. On 10 December 1942, the Polish government-in-exile published a 16-page report addressed to the Allied governments, titled The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland.[lower-alpha 5]

On 17 December 1942, as the answer to Raczyński's Note, the Allies issued the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations, a formal declaration confirming and condemning Nazi extermination policy toward the Jews and describing the ongoing events of the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Europe.[24] The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden.[25]

The death camps were discussed between American and British officials at the Bermuda Conference in April 1943.[26] On 12 May 1943, Polish government-in-exile member and Bund leader Szmul Zygielbojm committed suicide in London to protest the inaction of the world with regard to the Holocaust,[27] stating in part in his suicide letter:

I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being killed. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave. By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.[28]

The large camps near Auschwitz were finally surveyed by plane in April 1944. While all important German cities and production centers were bombed by Allied forces until the end of the war, no attempt was made to interdict the system of mass annihilation by destroying pertinent structures or train tracks, even though Churchill was a proponent of bombing parts of the Auschwitz complex. The US State Department was aware of the use and the location of the gas chambers of extermination camps but refused to bomb them.[29][lower-alpha 6] Throughout and after the war, the British government pressed leaders of European nations to prevent illegal Jewish immigration into Palestine and sent ships to block the sea-route to Palestine, turning back many Jewish refugees found attempting to illegally enter the region.[30]

German people

The debate continues on how much average Germans knew about the Holocaust. Robert Gellately, a historian at Oxford University, conducted a widely respected survey of the German media before and during the war and concluded that there was substantial participation and consent from large numbers of ordinary Germans in various aspects of the Holocaust, that German civilians frequently saw columns of slave laborers, and that the basics of the concentration camps, if not the extermination camps, were widely known.[31] The German scholar, Peter Longerich, in a study looking at what Germans knew about the mass murders concluded that: "General information concerning the mass murder of Jews was widespread in the German population."[32] Longerich estimates that before the war ended, 32 to 40 percent of the population had knowledge about mass killings (not necessarily the extermination camps).[33]

British historian Nicholas Stargardt presents evidence of widespread public knowledge, agreement, and collusion concerning the destruction of European Jewry, as well of the insane, feeble, disabled, Poles, Roma, and other nationals.[34] His evidence includes speeches by Nazi leaders,[35] which were broadcast or heard by a wide audience that included mention or inferences related to destroying the Jews, along with letters written between soldiers and their families describing the slaughter.[36] Historian Claudia Koonz relates how reports from the Nazi security service (SD) described the public opinion as favorable where it concerned the killing of Jews.[37] Using these same SD reports from the war years, along with a great many memoirs, diaries, and other descriptive material, historian Lawrence D. Stokes concluded that much, although not all, of the terror inflicted on the Jewish people was generally understood in the German public. Marlis Steinert came to an opposite conclusion through her own studies, contending that only a few were aware of the immense scale of the atrocities.[38] French historian, Christian Ingrao, reminds readers that one must take into consideration the possible extent to which SD reports were manipulated by the Nazi propaganda machine when reviewing them.[39] Historian Helmut Walser Smith remarks of the German people: "They were hardly indifferent to it; the responses range from outrage to affirmation to worry, especially toward the end of the war, when anxiety about accountability increased. That their imagination did not press to the particulars is not astounding. Nor is it astounding that few failed to imagine Auschwitz. The idea that not the killers go to the Jews, but the Jews are delivered up to industrial killing centers—this, in fact, was without historical precedent."[40]

Historian Eric A. Johnson and sociologist Karl-Heinz Reuband conducted interviews with more than 3,000 Germans and 500 German Jews about daily life in the Third Reich. From the Jewish questionnaires, the authors found that German society was not nearly as rife with antisemitism as one might otherwise have believed, but this changed dramatically with Hitler's ascension to power.[41] German Jews claimed that they knew of the Holocaust from a wide range of sources, which included radio broadcasts from Italy and what they heard from friends or acquaintances, but they did not know details until 1943.[42] Responses from non-Jewish Germans indicate that "the majority of Germans identified with the Nazi regime."[43] Contrary to many other accounts and/or historical interpretations, which portray rule under the Nazis as terrifying for German citizens, most of the German respondents who participated in the interviews stated that they never really feared arrest from the Gestapo.[43][lower-alpha 7] Concerning the mass murder of the Jews, the survey results were contingent to some degree on geography, but roughly 27–29% of Germans had information about the Holocaust at some point before the war's end, and another 10–13% suspected something terrible was happening all along. Based on this information, Johnson and Reuband surmise that one-in-three Germans either heard or knew that the Holocaust was taking place before the end of the war from sources that included family members, friends, neighbors or professional colleagues.[45] Johnson suggests (in disagreement with his co-author) that it is more likely that about 50% of the German population were aware of the atrocities being committed against the Jewish people and other enemies identified by the Nazi regime.[46]

During the years 1945 through 1949, polls indicated that a majority of Germans felt that Nazism was a "good idea, badly applied". In a poll conducted in the American German occupation zone, 37% replied that 'the extermination of the Jews and Poles and other non-Aryans was necessary for the security of Germans'.[47][lower-alpha 8] Sarah Ann Gordon in Hitler, Germans, and the Jewish Question notes that the surveys are very difficult to draw conclusions from as respondents were given only three options from which to choose: (1) Hitler was right in his treatment of the Jews, to which 0% agreed; (2) Hitler went too far in his treatment of the Jews, but something had to be done to keep them in bounds - 19% agreed; and (3) The actions against the Jews were in no way justified - 77% agreed. She also noted that another revealing example emerges from the question of whether an Aryan who marries a Jew should be condemned, a question to which 91% of the respondents answered "No". To the question: "All those who ordered the murder of civilians or participated in the murders should be made to stand trial", 94% responded "Yes".[48] Historian Tony Judt highlights how denazification and the subsequent fear of retribution from the Allies likely obscured justice due to some of the perpetrators and camouflaged underlying societal truths.[49]

Public recollection from Germans about the atrocities was also "marginalized by postwar reconstruction and diplomacy" according to historian Nicholas Wachsmann; a delay, which obscured the complexities of understanding both the Holocaust and the concentration camps that aided in its facilitation.[50] Wachsmann notes how the German people often claimed that the crimes occurred behind their backs and were perpetrated by Nazi fanatics, or that they frequently dodged responsibility by equating their suffering with that of the prisoners, avowing they too had been victimized by the National Socialist regime.[51] Initially the memory of the Holocaust was repressed and set aside, but eventually, the young Federal Republic of Germany commenced its own investigations and trials.[52] Political pressure on the prosecutors and judges tempered any extensive probes and very few systematic investigations in the first decade after the war took place.[53] Later research efforts in Germany revealed that there were a "myriad" of links between the wider population and the SS camps.[54] In Austria—once part of the Greater German Reich of the Nazis—the situation was much different, as they conveniently evaded accountability through the trope of being the Nazis' first foreign victim.[55]

Implementation

During the perpetration of the Holocaust, participants came from all over Europe but the impetus for the pogroms was provided by German and Austrian Nazis. According to Holocaust historian, Raul Hilberg, the "anti-Jewish work" of the regime was "carried out in the civil service, the military, business, and the party" where "every specialization was utilized" and "every stratum of society was represented in the envelopment of the victims."[56] Sobibor death camp guard Werner Dubois stated:

I am clear about the fact that annihilation camps were used for murder. What I did was aiding in murder. If I should be sentenced, I would consider that correct. Murder is murder. In weighing the guilt, one should not in my opinion consider the specific function in the camp. Wherever we were posted there: we were all equally guilty. The camp functioned in a chain of functions. If only one element in that chain is missing, the entire enterprise comes to a stop.[57]

In an entry in the Friedrich Kellner diary, "My Opposition", dated 28 October 1941, the German justice inspector recorded a conversation he had in Laubach with a German soldier who had witnessed a massacre in Poland.[58][lower-alpha 9] French officials at the Parisian branch of the Barclays Bank volunteered the names of their Jewish employees to Nazi authorities, and many of them ended up in the death camps.[59] An insightful perspective is provided by Konnilyn G. Feig, who wrote:

Hitler exterminated the Jews of Europe. But he did not do so alone. The task was so enormous, complex, time-consuming, and mentally and economically demanding that it took the best efforts of millions of Germans... All spheres of life in Germany actively participated: Businessmen, policemen, bankers, doctors, lawyers, soldiers, railroad and factory workers, chemists, pharmacists, foremen, production managers, economists, manufacturers, jewelers, diplomats, civil servants, propagandists, film makers and film stars, professors, teachers, politicians, mayors, party members, construction experts, art dealers, architects, landlords, janitors, truck drivers, clerks, industrialists, scientists, generals, and even shopkeepers—all were essential cogs in the machinery that accomplished the final solution.[60]

Additional scholars also point out that a wide range of German soldiers, officials, and civilians were in some way involved in the Holocaust, from clerks and officials in the government to units of the army, police, and the SS.[61][lower-alpha 10] Many ministries, including those of armaments, interior, justice, railroads, and foreign affairs, had substantial roles in orchestrating the Holocaust; similarly, German physicians participated in medical experiments and the T-4 euthanasia program as did civil servants;[62] German physicians also made the selections as to who was fit to work and who would die at the concentration camps.[63] Though there was no single department in charge of the Holocaust, the SS and Waffen-SS under Himmler had a leading role and operated with military efficiency in murdering enemies of the Nazi state. From the SS came the SS-Totenkopfverbände concentration camp guard units, the Einsatzgruppen killing squads, and the main administrative offices behind the Holocaust, including the RSHA and WVHA.[64][65] The regular army participated in the atrocities along with the SS on some occasions by taking part in the massacre of Jews in the Soviet Union, Serbia, Poland, and Greece. The German Army also logistically supported the Einsatzgruppen, helped form the ghettos, ran prison camps, occasionally provided concentration camp guards, transported prisoners to camps, had medical experiments performed on prisoners, and substantially used slave labor.[66] Significant numbers of Wehrmacht soldiers accompanied the SS in their deadly tasks or provided other forms of support for killing operations.[67] The murders by the Einsatzgruppen required cooperation between the Einsatzgruppen chief and Wehrmacht unit commander so they could coordinate and control access to and from the execution grounds.[68]

Obedience

Stanley Milgram was one of a number of post-war psychologists and sociologists who tried to address why people obeyed immoral orders in the Holocaust. Milgram's findings demonstrated that reasonable people, when instructed by a person in a position of authority, obeyed commands entailing what they believed to be the suffering of others. After making his results public, Milgram sparked a direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both" his laboratory experiments and the Holocaust. Professor James Waller, Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly Chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments "do not correspond well" to the Holocaust events:[69]

- The subjects of Milgram's experiments were assured in advance that "no permanent physical damage would result from their actions." However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

- Milgram's guards did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an "intense devaluation of the victims" through a lifetime of personal development.

- The subjects were not selected for sadism or loyalty to Nazi ideology, and often "exhibited great anguish and conflict" in the experiment, unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution (see Holocaust trials), who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

- The experiment lasted for an hour, insufficient time for participants to consider the moral implications of their actions. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[70]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

My own view is that Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.[71]

Religious hatred and racism

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Jews were subjected to antisemitism based on Christian theology, which blamed them for rejecting and killing Jesus.[72] Numerous attempts were made by early Christians to convert the Jews to Christianity in the collective, but when they refused, this made them "pariahs" in the eyes of many Europeans.[73] The consequences which they suffered for resisting conversion to Christianity were varied. An extensive series of attacks were committed against Jews as a result of the religious fervor which accompanied the First and Second Crusades (1095–1149).[73] Jews were slaughtered in the wake of the Italian famine (1315–1317), attacked following the outbreak of the Black Death in the Rhineland in 1347, expelled from both England and Italy in the 1290s, from France in 1306 and 1394, from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.[74] By the time of the Reformation in the 16th century, historian Peter Hayes stresses that "hatred of Jews was widespread" throughout Europe.[75]

Martin Luther (a German leader of the Protestant Reformation) made a specific written call for harsh persecution of the Jewish people in On the Jews and Their Lies, published in 1543. In it, he urged that Jewish synagogues and schools be set on fire, prayer books destroyed, rabbis forbidden to preach, homes razed, and property and money confiscated.[76] Luther argued that Jews should be shown no mercy or kindness, should have no legal protection and that these "poisonous envenomed worms" should be drafted into forced labor or expelled for all time.[77] American historian Lucy Dawidowicz asserted in her book The War Against the Jews that a clear path of antisemitism passes from Luther to Hitler and that "modern German anti-Semitism is the bastard child of Christian anti-Semitism and German nationalism."[78] Even after the Reformation, Catholics and Lutherans continued to persecute Jews, accusing them of blood libels and subjecting them to pogroms and expulsions.[79][80] The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence of the Völkisch movement in Germany and Austria-Hungary, which was developed and incentivized by authors like Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement presented a pseudo-scientific, biologically based form of racism that viewed Jews as a race whose members were locked in mortal combat with the Aryan race for world domination.[81]

Some authors, such as liberal philosopher Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951),[82] Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist, historian Hajo Holborn, and Ugandan academic Mahmood Mandani, have also linked the Holocaust to colonialism, but moreover, place the tragedy into the context of the European tradition of antisemitism and the genocide of colonized peoples.[83] Arendt claimed for instance that nationalism and imperialism were literally bridged together by racism.[84] Pseudo-scientific theories elaborated upon during the 19th century (e.g. Arthur de Gobineau's 1853 Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races) were fundamental in preparing the conditions for the Holocaust according to some scholars.[85] While other historical episodes of wholesale slaughter exist, there are still scholars who remain adamant about the "uniqueness" of the Holocaust, as compared to other genocides.[86] Philosopher Michel Foucault also traced the origins of the Holocaust to "racial policies" and "state racism", which are subsumed within the framework of "biopolitics".[87]

The Nazis considered it their duty to overcome natural compassion and execute orders for what they believed to be higher ideals; members of the SS, in particular, perceived that they had a state-legitimized mandate and obligation to eliminate those perceived as racial enemies.[88] Some of the heinous acts committed by the Nazis have been attributed to crowd psychology, and Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) provided influence to Hitler's infamous tome, Mein Kampf.[89] Le Bon claimed that Hitler and the Nazis used propaganda to deliberately shape group-think and related behaviors, especially in cases where people committed otherwise aberrant violent acts due to the anonymity resultant from being a member of the collective.[90] Sadistic acts of this sort were notable in the case of the genocide committed by members of the Croatian Ustashe, whose enthusiasm and sadism in their killings of Serbs appalled the Italians and Germans to the point that the German Army field police "moved in and disarmed them" at one point.[91] One might describe the behavior of the Croatians as a sort of quasi-religious eliminationist opportunism, but this same thing might be said of the Germans, whose antisemitism was likewise religious and racialist in nomenclature.[92]

A controversy erupted in 1997 when historian Daniel Goldhagen argued in Hitler's Willing Executioners that ordinary Germans were knowing and willing participants in the Holocaust, which he writes, had its roots in a deep racially motivated eliminationist antisemitism that was uniquely manifested in German society.[93] Historians who disagree with Goldhagen's thesis argue that, while antisemitism undeniably existed in Germany, Goldhagen's idea of a uniquely German "eliminationist" version is untenable.[94] In complete contrast to Goldhagen's position, historian Johann Chapoutot observes,

Culturally speaking, the Nazi ideology advanced by the NSDAP contained only an infinitesimal number of ideas that were genuinely German in origin. Racism, colonialism, anti-Semitism, social Darwinism, and eugenics did not originate between the Rhine and the Memel. Practically speaking, we know the Shoah would have been considerably less murderous if French and Hungarian police forces—not to mention Baltic nationalists, Ukrainian volunteer forces, Polish anti-Semites, and collaborationist politicians, to name only a few—had not supported it so fully and so swiftly: whether or not they knew where the convoys were headed, they were more than happy to rid themselves of their Jewish populations.[95]

Functionalism versus intentionalism

A major issue in contemporary Holocaust studies is the question of functionalism versus intentionalism. The terms were coined during the Cumberland Lodge Conference in May 1979 which was entitled, "The National Socialist Regime and German Society" by the British Marxist historian Timothy Mason in order to describe two schools of thought about the origins of the Holocaust.[96]

Intentionalists hold the view that the Holocaust was the result of a long-term master plan on the part of Hitler, and they also believe that he was the driving force behind it.[97] However, functionalists hold the view that Hitler did not have a master plan for genocide and based on this view, they see the Holocaust as coming from the ranks of the German bureaucracy, with little or no involvement on the part of Hitler.[98] Within the content of Hitler biographies which were written by Joachim Fest and Alan Bullock, one encounters a "Hitler-centric explanation for genocide" even though other psycho-historians like Rudolph Binion, Walter Langer, and Robert Waite raised issues about Hitler's ability to make rational decisions; nonetheless, his antisemitism remained unquestioned, the latter authors merely juxtaposed it against his general mental health.[99]

Historian and intentionalist Lucy Dawidowicz argued that the Holocaust was planned by Hitler from the very beginning of his political career, which can be traced back to his traumatic experience at the end of the First World War.[100] Other intentionalists, such as Andreas Hillgruber, Karl Dietrich Bracher, and Klaus Hildebrand, have suggested that Hitler had decided upon the Holocaust sometime in the early 1920s.[101] Historian Eberhard Jäckel postulates that the extermination order placed upon the Jews may have occurred during the summer of 1940.[102] Another intentionalist historian, the American Arno J. Mayer, argued that Hitler first ordered the mass murder of the Jews in December 1941, due principally to the failed Blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union.[103] Saul Friedländer has argued that Hitler was an extreme antisemite early on and drove Nazi policy to exterminate the Jews, but he also recognizes the technocratic rationality of the regime that helped bring Hitler's ideological goals to fruition.[104] While others, like Gerhard Weinberg, remain in the intentionalist camp and see Hitler's part as essential to the unfolding of the Final Solution—he also points out the importance of Nazi ideological imperatives such as the Wannsee Conference, and like many scholars, demonstrates that there is still "much to be discovered and learned."[105]

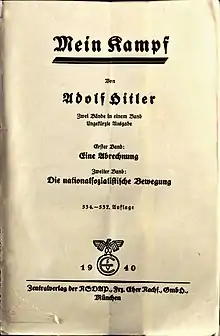

Functionalists such as Hans Mommsen, Martin Broszat, Götz Aly, Raul Hilberg, and Christopher Browning hold that the Holocaust was started in 1941–1942 either as a result of the failure of the Nazi deportation policy and/or the impending military losses in Russia.[106] Functionalists contend that what some see as extermination fantasies outlined in Hitler's Mein Kampf and other Nazi literature were simply propaganda and did not constitute concrete plans. In Mein Kampf, Hitler repeatedly states his inexorable hatred of the Jewish people, but nowhere does he proclaim his intention to exterminate them. They also argue that, in the 1930s, Nazi policy aimed at making life so unpleasant for German Jews that they would leave Germany.[107] Adolf Eichmann was in charge of facilitating Jewish emigration by whatever means possible from 1937[108] until 23 October 1941, when German Jews were forbidden to leave.[109] Functionalists see the SS's support in the late 1930s for Zionist groups as the preferred solution to the "Jewish Question" as another sign that there was no masterplan for genocide. Essentially the view of functionalists concerning the Holocaust is that it came about via improvisation as opposed to deliberate planning.[110]

To that end, functionalists argue that, in German documents from 1939 to 1941, the term "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" was meant to be a "territorial solution"; that is, the entire Jewish population was to be expelled somewhere far from Germany.[111] At first, the SS planned to create a gigantic Jewish reservation in the Lublin, Poland area, but the so-called "Lublin Plan" was vetoed by Hans Frank, the Governor-General of occupied Poland, who refused to allow the SS to ship any more Jews to the Lublin area after November 1939. The reason Frank vetoed the "Lublin Plan" was not due to any humane motives, but rather because he was opposed to the SS "dumping" Jews into the Government-General.[112] In 1940, the SS and the German Foreign Office had the so-called "Madagascar Plan" to deport the entire Jewish population of Europe to a "reservation" on Madagascar.[113] The "Madagascar Plan" was canceled because Germany could not defeat the United Kingdom and until their blockade of Nazi-occupied Europe was broken, the "Madagascar Plan" could not be put into effect.[114] Finally, functionalist historians have made much of a memorandum written by Himmler in May 1940 explicitly rejecting extermination of the entire peoples as "un-German" and recommending to Hitler instead, the "Madagascar Plan" as the preferred "territorial solution" to the "Jewish Question".[115][116] Not until July 1941 did the term "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" come to mean extermination.[117]

Recently, a synthesis of the two schools has emerged that has been championed by diverse historians such as the Canadian historian Michael Marrus, the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer, and the British historian Ian Kershaw that contends Hitler was the driving force behind the Holocaust, but that he did not have a long-term plan and that much of the initiative for the Holocaust came from below in an effort to meet Hitler's perceived wishes. As historian Omer Bartov relates, "the "intentionalists" and "functionalists" have gradually come closer, as further research now seems to indicate that the more extreme new interpretations are just as impossible to sustain as the traditional ones."[118]

Involved

Adolf Hitler

Most historians take the view that Hitler was the opposite of a pragmatist: his overriding obsession was hatred of the Jews, and he showed on a number of occasions that he was willing to risk losing the war to achieve their destruction. There is no "smoking gun" in the form of a document that shows Hitler ordering the Final Solution. Hitler did not have a bureaucratic mind and many of his most important instructions were given orally.[119] There is ample documentary evidence, however, that Hitler desired to eradicate Jewry and that the order to do so originated from him, including the authorization for mass deportations of the Jews to the east beginning in October 1941.[120] He cannot have imagined that these hundreds of thousands of Jews would be housed, clothed, and fed by the authorities of the Government-General, and in fact Hans Frank frequently complained that he could not cope with the influx.[121][122]

Historian Paul Johnson writes that some writers, such as David Irving, have claimed that because there were no written orders, "the Final Solution was Himmler's work and […] Hitler not only did not order it but did not even know it was happening". Johnson states, however, that "this argument will not stand up. The administration of the Third Reich was often chaotic but its central principle was clear enough: all key decisions emanated from Hitler."[119]

According to Kershaw, "Hitler's authority—most probably given as verbal consent to propositions usually put to him by Himmler—stood behind every decision of magnitude and significance."[123] Hitler continued to be closely involved in the "Final Solution".[124] Kershaw also points out that, "in the wake of the German military crisis following the catastrophe at Stalingrad" that "Hitler took a direct hand" in convincing his Hungarian and Romanian allies to "sharpen the persecution" of the Jews.[125] Hitler's role in the Final Solution was often indirect rather than overt, frequently granting approval rather than initiating. The unparalleled outpourings of hatred were a constant even amid all the policy shifts of the Nazis. They often had propaganda or mobilizing motives, and usually remained generalized. Even so, Kershaw remains adamant that Hitler's role was decisive and indispensable in the unfolding of the "Final Solution".[126]

In the following widely cited speech made on 30 January 1939, Hitler gave a speech to the Reichstag which included the statement:

I want to be a prophet again today: if international finance Jewry in Europe and beyond should succeed once more in plunging the peoples into a world war, then the result will be not the Bolshevization of the earth and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.[127]

On 30 January 1942 at the Sports Palace in Berlin, Hitler told the crowd:

And we say that the war will not end as the Jews imagine it will, namely with the uprooting of the Aryans, but the result of this war will be the complete annihilation of the Jews.[128]

According to historian Klaus Hildebrand, moral responsibility for the Holocaust resides with Hitler and was nothing less than the culmination of his pathological hatred of the Jews, which for all intents and purposes formed the basis of Nazi genocide and drove the regime to pursue its racial-eliminationist goals.[129] Whether or not Hitler gave a direct order for the implementation of the Final Solution is immaterial and nothing more than a red herring, which fails to recognize Hitler's leadership style, particularly since his verbal commands were sufficient to launch initiatives—due largely to the fact that his subordinates were always "working towards the Führer" in an effort to implement "his totalitarian vision" even in cases "without written authority."[130] Throughout Gerald Fleming's notable work, Hitler and the Final Solution, he demonstrates that on numerous occasions, Himmler mentioned a "Führer-Order" concerning the annihilation of the Jews, which indicates that at the very least, Hitler verbally issued a command on the subject.[131]

Journal entries from Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels support the position that Hitler was the driving force behind the destruction of the Jews as well; Goebbels wrote that Hitler followed the subject closely and described the Führer as "uncompromising" about eliminating the Jews.[132] As historian David Welch asserts, if one takes the scale of the logistical operations that the Holocaust comprised (in the middle of a worldwide war) into consideration alone, it is nearly impossible that the extermination of so many people and the coordination of such an extensive effort could have occurred without Hitler's authorization.[133]

Other Nazi leaders

While significant numbers of Germans and other Europeans collectively participated in the Holocaust, it was Hitler and his Nazi followers who share the greatest responsibility for incentivizing, coercing, and/or overseeing the extermination of millions of people.[134] Among those most responsible for the Final Solution were Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, Adolf Eichmann, Odilo Globocnik, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Heinrich Müller, Theodor Eicke, Richard Glücks, Friedrich Jeckeln, Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, Rudolf Höss, Christian Wirth, and Oswald Pohl. Key roles were also played by Fritz Sauckel, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick and Robert Ley.[135]

Other top Nazi leaders such as Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, and Martin Bormann contributed in various ways, whether administratively supporting killing efforts or providing ideological fodder to encourage the Holocaust.[136] For example, Goebbels carried on an intensive antisemitic propaganda campaign and also had frequent discussions with Hitler about the fate of the Jews.[137] He was aware throughout that the Jews were being exterminated, and completely supported this decision.[138] In July 1941, Göring issued a memo to Heydrich ordering him to organise the practical details of a solution to the "Jewish Question". This led to the Wannsee Conference held on 20 January 1942, where Heydrich formally announced that genocide of the Jews of Europe was now an official Reich policy.[139] That same year, Bormann signed the decree of 9 October 1942 prescribing that the permanent Final Solution in Greater Germany could no longer be solved by emigration, but only by the use of "ruthless force in the special camps of the East", that is, extermination in Nazi death camps.[140]

Although the Nazi regime is often depicted as a super-centralized vertically hierarchical state, individual initiative was an important element in how Nazi Germany functioned.[141] Millions of people were rounded up, bureaucratically processed and transported across Europe due to the vigorous initiative of those Nazis most committed to carrying out their duties to the state, an operation involving thousands of officials and a great deal of paperwork. This was a coordinated effort among the SS and its sprawling police apparatus with the Reich ministries and the national railways, all under the supervision of the Nazi Party.[142] Most of the Party's regional leaders (Gauleiters) also knew of the Holocaust since many were present for Himmler's October 1943 speech at Posen, during which he explicitly mentioned the extermination of the Jews.[143]

German military

The extent to which the officers of the regular German military knew of the Final Solution has been much debated. Political imperatives in postwar Germany led to the army being generally absolved from responsibility, apart from the handful of "Nazi generals" such as Alfred Jodl and Wilhelm Keitel who were tried and hanged at Nuremberg. There is an abundance of evidence, however, that the top officers of the Wehrmacht certainly knew about the murders and in a number of instances, approved and/or sanctioned them.[144] The exhibit "War of Extermination: The Crimes of the Wehrmacht"[lower-alpha 11] showed the extent to which the military was involved in the Holocaust.[145][146]

It was particularly difficult for commanders on the eastern front to avoid knowing what was happening in the areas behind the front. Many individual soldiers photographed the massacres of Jews by the Einsatzgruppen.[147] Some generals and officers, such as Walther von Reichenau, Erich Hoepner, and Erich von Manstein, actively supported the work of the Einsatzgruppen.[148] A number of Wehrmacht units provided direct or indirect assistance to the Einsatzgruppen—all the while mentally normalizing amoral behaviors in the conduct of war through specious justification that they were destroying the Reich's enemies.[149] Many individual soldiers who ventured to the killing sites behind the lines voluntarily participated in the mass shootings.[150] Cooperation between the SS police units and Wehrmacht also occurred when they took hostages and carried out reprisals against partisans, particularly in the Eastern theater, where the war took on the complexion of a racial war as opposed to the conventional one being fought in the West.[151]

Other front-line officers went through the war without coming into direct contact with the machinery of extermination, choosing to focus narrowly on their duties and not noticing the wider context of the war. On 20 July 1942, an extermination unit under the command of Walther Rauff was sent to Tobruk and assigned to the Afrika Korps led by Erwin Rommel. However, since Rommel was 500 km away at the First Battle of El Alamein, it is unlikely that the two were able to meet.[152] The plans for Einsatzgruppe Egypt were set aside after the Allied victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein.[153] Historian Jean-Christoph Caron opines that there is no evidence that Rommel knew of or would have supported Rauff's mission.[154] Relations between some Army commanders and the SS were not friendly, as officers occasionally refused to co-operate with Himmler's forces; General Johannes Blaskowitz for instance, was relieved of his command after officially protesting about SS atrocities in Poland.[155][lower-alpha 12] Such behaviors were uncommon, however, as a significant portion of the German military acculturated to the norms of the Nazi regime and the SS in particular, and were likewise censurable for carrying out atrocities during the course of the Second World War.[156]

Other states

.jpg.webp)

Although the Holocaust was planned and directed by Germans, the Nazi regime found willing collaborators in other countries, both those allied to Germany and those under German occupation and by 1942, the atrocities across the continent became a "pan-European program."[157] The civil service and police of the Vichy regime in occupied France actively collaborated in persecuting French Jews.[158] Germany's allies, Italy, Finland, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, were all pressured to introduce anti-Jewish measures. Bulgaria refused to co-operate, and all 50,000 Bulgarian Jews survived (though most lost their possessions and many were imprisoned), but thousands of Greek and Yugoslavian Jews were deported from the Bulgarian-occupied territories.[159] Finland officially refused to participate in the Holocaust and only 7 out of 300 Jewish alien refugees were turned over to the Germans.[160] The Hungarian regime of Miklós Horthy also refused to cooperate until the German invasion of Hungary in 1944, after which its 750,000 Jews were no longer safe.[161] Between May through July 1944, upwards of 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary to Auschwitz.[162] The Romanian regime of Ion Antonescu actively persecuted Jews, murdering some 120,000 of them.[163][164] The German puppet regime in Croatia actively persecuted Jews on its own initiative.[165][166]

The Nazis enlisted support for their programs in all the countries they occupied, although their recruitment methods differed in various countries according to Nazi racial theories. In the "Nordic" countries of Denmark, Norway, Netherlands, and Estonia they tried to recruit young men into the Waffen-SS, with sufficient success to create the "Wiking" SS division on the Eastern Front, many of whose members fought for Germany with great fanaticism until the end of the war.[167] In Lithuania and Ukraine, on the other hand, they recruited large numbers of auxiliary troops that were used for anti-partisan work and guard duties at extermination and concentration camps.[168]

In recent years, the extent of local collaboration with the Nazis in Eastern Europe has become more apparent. Historian Alan Bullock writes: "The opening of the archives both in the Soviet Union and in Eastern Europe has produced incontrovertible evidence [of] ... collaboration on a much bigger scale than hitherto realized of Ukrainians and Lithuanians as well as Hungarians, Croats and Slovaks in the deportation and murder of Jews."[169] Historians have been examining the question of whether it is fair to connote the Holocaust as a European Project. Historian Dieter Pohl has estimated that more than 200,000 non-Germans "prepared, carried out and assisted in acts of murder"; that is about the same number as Germans and Austrians.[170] Such numbers have elicited a similar reaction from other historians; Götz Aly for instance, has come to the conclusion that the Holocaust was in fact a "European project."[171] While the Holocaust was perpetrated at the urging of the Nazis and constituted part of the SS vision for a "pan-European racial community", the subsequent outbursts of antisemitic violence in Croatia, France, Romania, Slovakia, the Baltic states among others, make the catastrophe a "European project" according to historian Dan Stone.[172]

Belgium

In Belgium the state has been accused of having actively collaborated with Nazi Germany. An official 2007 report commissioned by the Belgian senate concluded that the Belgians were indeed complicit in participating in the Holocaust. According to the report, the Belgian authorities "adopted a docile attitude providing collaboration unworthy of a democracy in its treatment of Jews."[173] The report also identified three crucial moments that showed the attitude of Belgian authorities toward the Jews: (1) During the autumn of 1940 when they complied with the order of the German occupier to register all Jews even though it was contrary to the Belgium constitution; this led to a number of measures including the firing of all Jews from official positions in December 1940 and the expelling of all Jewish children from their schools in December 1941;[174] (2) In summer 1942, when over one thousand Jews were deported to the death camps, particularly Auschwitz during the month of August. This was only the first of such actions as the deportations to the east continued resulting in the death of some 25,000 people;[175] and (3) At the end of 1945, the Belgian state officials decided that its authorities bore no legal responsibility for the persecution of the Jews, even though many Belgian police officers participated in the rounding up and deportation of Jews,[176] particularly in the Flemish part of Belgium.[177]

However, collaboration is not the whole story. While there is little doubt that there were strong antisemitic feelings in Belgium, after November 1942, the German roundups became less successful as large-scale rescue operations were carried out by ordinary Belgians. Many bankers, notaries, and judges—people who had access to information about property, accounts, and commercial registers—refused to be complicit in the expropriation of Jewish property, which elicited complaints from Nazi authorities.[178] These actions (among others) resulted in the survival of about 25,000 Jews from Belgium.[179] Unlike other states, which were immediately annexed, Belgium was initially placed under German military administration, which the Belgian authorities exploited by refusing to carry out some of the Nazi directives against the Jews. Roughly 60 percent of Belgium's Jews, who were there at the start of the war, survived the Final Solution.[180]

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, mainly through the influence of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, saved nearly all of its indigenous Jewish population from deportation and certain death. This is not to imply that Bulgaria was entirely blameless, as they passed special laws to confiscate Jewish property and remove them from public service in early 1941.[181] When this law came into effect on 23 January 1941—signed by Tsar Boris III—Jews were also forbidden from marrying Christians, they could no longer serve in the Bulgarian military, became subject to forced labor, and could no longer vote, nor could they change residence without police authorization.[182] Once civil and military administration over parts of Northern Greece and Macedonia were turned over to Bulgaria by Germany, Bulgarian authorities deported Jews from those territories to concentration camps. Originally SS Captain Theodor Dannecker and the head of the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, Alexander Belev, agreed to deport as many as 20,000 Jews from Macedonia and Thrace.[183] These deportations were set to be completed by May 1943.[184] Belev had agreed to these measures without the knowledge or approval from officials in the Bulgarian government, which sparked protests that reached the Bulgarian National Assembly in Sofia.[185] Before the matter was over, however, Bulgaria had deported some 11,000 foreign Jews to Nazi-held territory.[186] Once those Jews were handed over to the Germans, they were sent to the extermination camp at Treblinka, where they perished.[187]

Channel Islands

Channel Islands police collaborated with the Nazis deporting local Jews, some of whom were sent to Auschwitz in 1942, others were deported in 1943 as retaliation for the British commando raid on the small Channel Island of Sark when most of the Jews were shipped to internment camps in France and Germany.[188] On the Channel Island of Alderney a labor camp for Jews was established, one which was notable for the brutality of the German guards; hundreds of Jews were murdered there and 384 were buried within the camp itself, while many others were simply dumped into the sea.[189] Some 250—mostly French—Jews perished on a ship headed from Germany to the Alderney camp when it was sunk by the Royal Navy on 4 July 1944.[190]

Croatia

Croatia was a puppet state which was created by the Germans and ruled by the vehemently racist head of the Ustasha,[lower-alpha 13] Ante Pavelić.[191] As early as May 1941, the Croatian government forced all Jews to wear the yellow badge and by the summer of that same year, they enacted laws that excluded them from both the economy and society.[192][193] Within those first few months in power, the Ustasha also demolished the main synagogue in Zagreb.[194] The Croatian Ustaše regime killed thousands of people, the majority of whom were Serbs, (estimates vary widely, but most modern and qualified sources put the number of people who were killed at around 45,000 to 52,000), about 12,000 to 20,000 Jews and 15,000 to 20,000 Roma,[195] primarily in the Ustasha's Jasenovac concentration camp which was located near Zagreb.[196] Historians Donald Niewyk and Francis Nicosia provide higher estimates for the number of people who were killed, reporting the following ranges: 500,000 Serbs, 25,000 Gypsies, and 32,000 Jews; most of whom (75%) were murdered, not by the Nazis but by the Croatians themselves.[197] Croatians murdered of their own volition as part of their own "large-scale political repopulation project," one with the obvious goal of ethnic cleansing.[198][lower-alpha 14] According to the 2001 census in Croatia, only 495 Jews were listed of the 25,000 Jews who had previously lived there before the Second World War, accounting for less than 1/10th of one percent of Croatia's population.[199]

Denmark

Due in part to the fact that the Germans were dependent upon an "uninterrupted supply of Danish agricultural products to the Reich" they tolerated the status quo of 6,500 Jews living undisturbed in Denmark.[200] Upset with German policies and wishing for democracy, the Danes began demonstrating against the Germans, which incited a military response from the Nazis that included dismantling the Danish military forces and correspondingly placing Danish Jews at increased risk.[201]

Most of the Danish Jews were saved by the unwillingness of the Danish government and people to acquiesce to the demands of the occupying forces and through their concerted efforts to ferry Danish Jews to Sweden during October 1943.[202] In total, this endeavor saved nearly 8,000 Jews from certain death; another 425 who were sent to Theresienstadt[lower-alpha 15] were also saved due to the determination of the Danes, and returned to their homes following the war.[204] About 1,500 of the roughly 8,000 Jews rescued by the Danes were recent refugees from Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Germany.[205]

Estonia

Prior to the Second World War, there were approximately 5,000 Estonian Jews.[206] With the Nazi invasion of the Baltics, the Nazi government found willing volunteers from this region to assist the Einsatzgruppen and auxiliary police, which enabled it to carry out mass genocide in this region.[207] About 50% of Estonia's Jewish population, aware of the fate that otherwise awaited them following the Nazi invasion, managed to escape to the Soviet Union;[208] virtually all those remaining were forced to wear badges identifying them as Jews, stripped of their property, and eventually murdered by Einsatzgruppe A and local collaborators before the end of 1941.[209] Right-wing Estonian units, known as the Omakaitse were among those who aided the Einsatzgruppen in murdering Jews.[210] During the winter of 1941–1942, Einsatzgruppe A operating in Ostland and the Army Group Rear reported having murdered 2,000 Jews in Estonia.[211] At the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, Estonia was reported to be Jew-free.[210] Jews from countries outside the Baltics were shipped there to be exterminated—as was the case for 7,130 Jews sent to Estonia in September 1943, where they were murdered within months.[212] An estimated 20,000 Jews were sent to labor camps in Estonia from elsewhere in Eastern Europe.[213]

Finland

Despite being at times a co-belligerent of Nazi Germany, Finland remained independent and its leadership flatly refused to cooperate with Heinrich Himmler's request to relinquish its 2,000 Jews.[160] Some Jews were even able to flee German-occupied Europe and make their way into Finland.[214] Only seven of the 300 alien Jews living in Finland were turned over to the Germans.[160] Even the deportation of a handful of Jews did not go unnoticed, as there were protests in Finland from members of its indigenous Social Democratic Party, by a number of Lutheran ministers, the Archbishop, and the Finnish Cabinet.[215] Like Denmark, Finland was one of only two countries in the orbit of Nazi domination that refused to cooperate fully with Hitler's regime.[216] These historical observations do not absolve all Finns, as some scholars point out—in particular, the Einsatzkommando Finnland was formed during the joint invasion of the Soviet Union, which received collaboration from Finnish police units and Finnish military intelligence in capturing partisans, Jews, and Soviet POWs as part of their operations—exactly how many of each group remains unclear and is a subject needing further research according to historian Paul Lubotina.[217]

France

Antisemitism, as the Dreyfus Affair had shown at the end of the 19th century, was widespread in France, especially among anti-republican sympathizers.[218] Long before the rise of the Nazis, antisemitism was so pronounced in France that, according to intellectual historian George Mosse, France seemed like it would be the country where racism might direct its political future.[219] Before the onset of World War II, there were roughly 350,000 Jews residing in France, with only 150,000 being native-born. Approximately 50,000 were refugees fleeing Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, while another 25,000 came to France from Belgium and Holland; the remaining Jews were arrivals to France in the 1920s and 30s from Eastern Europe.[220]

Once the Germans invaded, many Jews fled away from the advancing forces, but France's rapid collapse, both militarily and politically, the armistice, and the speed at which everything happened trapped many of them in southern France.[221] Philippe Pétain, who became the French premier after Paris had fallen to the German Army, arranged the surrender to Germany.[222] He then became the head of the Vichy government, which collaborated with the Nazis, claiming that it would soften the hardships of occupation.[223] Opposition to the German occupation of northern France and the collaborationist Vichy government was left to the French Resistance within France and the Free French Forces led by Charles de Gaulle outside France.[224] German occupation was quickly accompanied by harsh treatment; Jews were expelled from Alsace-Lorraine and their property was confiscated, whereas foreign Jews—around 32,000—were interned following a Vichy decree on 4 October 1940.[225] Additional discriminatory measures soon followed and intensified after the Nazis issued an ordinance on 27 September 1940; these were carried out by the French administration and included: identification requirements for Jews, a census to account for all Jews and businesses, expropriation and "Aryanization" of property, along with occupational restrictions and bans.[225] On 7 October 1940, Pétain's government repealed the Crémieux Decree, a move which deprived 117,000 Algerian-born French Jews of the civil rights they were granted in 1870.[226]

By the end of 1940, more Jews were arrested in Vichy France than in German-occupied France.[227] Another 1,112 Jews were arrested during French round-ups in May and December 1941; later, when they were deported, they constituted some of the earliest arrivals to Auschwitz at the end of March 1942.[228] Five thousand additional Jews were sent from France to Auschwitz at the end of April and during June 1942.[229] The chief of police for the Vichy government, René Bousquet, agreed to arrest foreign and stateless Jews in Vichy France starting in July 1942, and he acceded to having French police collaborate in arresting Jews in the occupied zone.[230] Per agreement between the Vichy government and the Nazis, another 10,000 Jews were added to the total being deported between 19 July and 7 August 1942.[231] Some 2,000 Jewish children whose parents had already been shipped to Auschwitz were also sent to the camp during the period 17–26 August 1942, and by the end of the year, the total figure of deportees from France reached 42,000 persons.[232] From the first transport of March 1942 to the last one during July 1944, as many as 77,911 Jews were deported from France to Poland.[233] [lower-alpha 16] Most of the Jews in France were transported to Auschwitz, but some were sent to Majdanek and Sobibór with a few ending up at Buchenwald.[235]

Greece

The Jews of Greece mainly lived in the area around Thessaloniki, where a large and influential Sephardi community had lived since the 15th century, where some 55,000 Jews comprised nearly 20% of the city.[236] Following the German invasion and occupation of Salonika in 1941, an antisemitic nationalist party called National Union of Greece (Ethniki Enosis Ellados, EEE), which had existed between 1927 and 1935, was revived by Nazi authorities.[237][lower-alpha 17]

The Greek governor, Vasilis Simonides, cooperated with the Nazi authorities and supplied local police forces to aide in deporting 48,500 Jews from Salonika to Auschwitz-Birkenau during March to August 1943.[239] Both Greeks and Germans looted the businesses and homes vacated by the expelled Jews.[183] Greek Jews residing in the areas occupied by Bulgaria were also deported following the deportations from Salonika. In March 1944, German forces and Greek police in Athens rounded up Jews and deported them. Upwards of 2,000 Jews from Corfu and another 2,200 from Rhodes were transported to concentration camps in June 1944.[240] Before the end of the war, over 60,000 Greek Jews were murdered, the vast majority of whom were sent to Auschwitz.[241]

Hungary

In March 1938, several years before the German occupation of Hungary, anti-Jewish measures were already enacted by the Hungarian Parliament in the wake of Prime Minister Kálmán Darányi's announcement about the need to solve the Jewish question.[242] This legislation and the second set of anti-Jewish laws restricted Jews from certain professions and economic sectors, it also forbade Jews from becoming Hungarian citizens by means of either marriage, naturalization, or legitimization. Approximately 90,000 Jews and their family members who relied on their support (upwards of 220,000 people) lost their means of economic survival and when the third anti-Jewish law went into effect, it nearly mirrored the Nazi Nuremberg Laws.[243]

Once the legal exclusion of Jews from Hungarian society was complete, the National Central Alien Control Office (Külföldieket Ellenőrző Országos Központi Hatóság, KEOKH), turned its attention almost exclusively to expelling "undesirable" Jews.[244] By the summer of 1941, the Hungarians carried out their first series of mass murders, and again in early January 1942, when they slaughtered 2,500 Serbs and 700 Jews, demonstrating that the political leadership in Hungary authorized the commission of atrocities even before the German occupation.[245] Sometime in August 1941, the Hungarian authorities deported 16,000 "alien" Jews, most of whom were shot by the SS and Ukrainian collaborators.[246] In the spring of 1942, the Hungarian Minister of Defense ordered the majority of Jewish forced labor to the theater of military operations. Due to this order, as many as 50,000 Jews worked in military forced-labor companies starting in the spring of 1942 through 1944.[247] Accompanying Hungarian troops during Operation Barbarossa, Jews in these units were poorly treated, insufficiently housed, ill-fed, routinely used to clear minefields, and placed in constant unnecessary danger; estimates indicate that "at least 33,000 Hungarian Jewish males in the prime of life" died in Russia.[248]

During parts of May through June 1944, some 10,000 Hungarian Jews were gassed on a daily basis at Auschwitz-Birkenau, a pace with which the crematoria could not keep up, resulting in many of the bodies being burned in open pits.[249] The 410,000 Jews murdered during this period represents the "largest single group of Jews murdered after 1942" according to historian Christian Gerlach.[250] Much of the efficiency with which the Germans were able to deport and murder Hungarian Jews stemmed from the "frictionless cooperation of Hungary's politicians, bureaucracy, and gendarmerie", and popular Hungarian antisemitism served to block any Jews trying to escape.[251] After the fascist Arrow Cross coup in October 1944, Arrow Cross militias shot as many as 20,000 Jews in Budapest and dumped their bodies into the Danube River between December 1944 and the end of January 1945.[252] Jews in labor battalions were sent on death marches into Germany and Austria.[253]

Nearly one-tenth of the Holocaust's Jewish victims were Hungarian Jews, accounting for a total of over 564,000 deaths; some 64,000 Jews had already been murdered prior to the German occupation of Hungary.[254] Despite the atrocities in Hungary, approximately 200,000 Jews in total survived the war.[255]

Italy

Among Germany's allies, Italy was not known for its antisemitism and had a relatively well-assimilated Jewish population; its policies were essentially about domination as opposed to "destruction." [256] National pride and the need to express sovereignty had as much to do with Italian behaviors as did any general benevolence towards the Jews.[256] Approximately 57,000 Jews resided in pre-war Italy, about 10,000 of whom were refugees from Austria and Germany, comprising less than one-tenth of one percent of the population.[257] An Italian law was passed in 1938 as part of Mussolini's effort to align his country more with Germany; the law restricted civil liberties of Jews. This effectively reduced the country's Jews to second-class status, though the Italians never made it official policy to deport Jews to concentration camps. Edging closer towards Germany, the Italian Ministry of the Interior established 43 camps where enemy "aliens" (to include Jews) were detained—these camps were not pleasant but they were "a far cry from the Nazi concentration camps."[258]

After the fall of Benito Mussolini and the Italian Social Republic, Jews started being deported to German camps by the Italian puppet regime, which issued a police order to that effect on 30 November 1943.[259] While Jews fled once the puppet regime came to power, the Italian police nonetheless captured and sent over 7,000 Jews to camps at Fossoli di Carpi and Bolzano, both of which served as assembly points for deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau.[260] Italian prisons were used to house Jews as well, the most infamous of them was San Vittore Prison in Milan where "torture and murder were common."[261] Nazi Germany's Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, complained throughout the war about Italy's "lax" policies against the Jews.[262] Nevertheless, through 1944, no less than 15 transports carrying around 3,800 Jews made their way from Italy to Auschwitz.[263] Estimates from a number of sources place the total death count for Italian Jews between 6,500 and 9,000.[264] The generally accepted death tolls for Italy are about 8,000 Jews and as many as 1,000 Roma.[265]

Latvia

Before the war over 93,000 Jews resided in Latvia, comprising less than 5 percent of the country's population.[266] Immediately in the wake of the German attack on the former Soviet Union in June 1941, Latvia was occupied and incorporated into the Reichskommissariat Ostland as Generalbezirk Lettland with a Latvian civil administration under the D. Heinrich Drechsler.[267] Latvian auxiliary forces aided the SS Einsatzgruppen by following behind the advancing German forces, shooting Jews who they lined up in anti-tank trenches.[268] Other instances of Latvian brutality against the Jews manifested before troops even arrived, as the local populations attacked and murdered entire communities across hundreds of small villages.[269] Zealous Latvians assisted the German forces in collecting all males between the ages of 16 and 60 in the city of Dvinsk for support operations; hundreds of Jewish males never returned from these duties as they were often murdered.[270] In the areas in and around Warsaw, Latvian guards accompanied the SS in securing the ghetto and deporting Jews to Treblinka.[271]

The former head of the Latvian police, Viktors Arājs, willingly collaborated with the Nazis by forming the Arājs Kommando, a Latvian volunteer police unit, which worked closely with the SS Einsatzgruppe A to murder Jews.[272] As early as July 1941, they were already burning synagogues in Riga.[273] According to historian Timothy Snyder, the Arājs Kommando shot 22,000 Latvian Jews at various locations after they had been brutally rounded up for this purpose by the regular police and auxiliaries, and were responsible for assisting in the murder of some 28,000 more Jews.[274] Aggregate figures indicate that around 70,000 Latvian Jews were murdered during the Holocaust.[211]

Liechtenstein

Only a handful of Jews lived in the small neutral state of Liechtenstein at the outbreak of the Second World War.[lower-alpha 18] Between 1933 and 1945, approximately 400 Jews were taken in by Liechtenstein, but another 165 were turned away.[276] According to a 2005 study, the royal family of Liechtenstein purchased once Jewish-owned property and furniture that the Nazis seized after annexing Austria and Czechoslovakia. Liechtenstein's royal family also rented inmates from Strasshof an der Nordbahn concentration camp near Vienna, where they employed forced labor on nearby royal estates.[277]

Lithuania

Nearly 7 percent of Lithuania's population was Jewish, totaling approximately 160,000 persons.[278] For the most part, the Nazis considered the majority of non-Jewish people in the Baltics as racially assimilable with the exception of Jews, against whom some discrimination was already present in Lithuania before the occupation, but it was generally confined to edicts against Jews being in certain occupations and/or educational discrimination.[279] Lithuania's Jewish population quickly swelled in the aftermath of the territorial arrangement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which proved a tumultuous time for many Jews who fled there to escape persecution; meanwhile, it increased the Jewish population of Lithuania to approximately 250,000.[280] Angry about the Nazi-Soviet pact, many Lithuanians began taking their anger out on the country's Jews by attacking them and their property.[281] The situation deteriorated further due to the see-saw of political power that started when the Soviet Army took control of Lithuania in June 1940 and persecuted thousands of its citizens through a program of Sovietization (approximately 17,000 Lithuanians were sent to Siberia right before the Germans arrived).[282] Many Jews were asked to join the short-lived Soviet government and were allowed integration into Lithuanian society. Just seven weeks later, however, the Nazis invaded and were greeted as liberators. Subsequent blame for the ill fortune that befell the Lithuanians under the Soviets landed on the Jews, which started even before the Germans had finished conquering the country;[283] Lithuanians carried out pogroms in at least 40 different places, where Jews were raped, severely injured, and murdered.[284] Blaming the Jews also afforded any Lithuanians who had cooperated with the Soviets the means to exonerate themselves by diverting attention onto a Jewish conspiratorial scapegoat.[285]

On 25 June 1941 Nazi forces arrived in Kaunas, where they witnessed local Lithuanians drag about 50 male Jews into the center of the city while one Lithuanian man beat them to death with a crowbar (cheered on by spectators) in a public display of brutality that shocked many Germans. After murdering all the Jews, the man climbed atop their corpses and played the Lithuanian national anthem on an accordion.[286] These deaths were part of the Kaunas pogrom during which many thousands of Jews were murdered by the Nazis with local acquiesance or assistance.[287] Mere weeks after arrival, the Nazis instituted a systematic campaign to eliminate the Jews of Lithuania by identifying them, rounding them up, guarding them, and transporting them to extermination sites—during which they were aided by Lithuanian soldiers and police.[288] The pace of murder increased and spread across Lithuania as the Germans consolidated their rule, sometimes by way of Lithuanian initiative, other times triggered at the arrival of Sipo-SD contingents.[289] Within the last 6 months of 1941 following the June invasion by Germany, the majority of Lithuanian Jews were executed, the biggest crime being the Ponary massacre.[290] The remnants trapped in ghettos were killed in occupied Lithuania and sent to Nazi death camps in Poland.[291] By the end of June 1941, around 80 percent of Lithuania's Jews had been "wiped out."[292] Scholars believe the overall Holocaust-related death rate in Lithuania was approximately 90 percent, making Nazi-occupied Lithuania the European territory with the lowest proportion of Jewish survivors from World War II. While estimates vary, the number of Lithuanian Jews murdered in the Holocaust is assessed to be between 195,000 and 196,000.[293]

Additionally, Lithuanian auxiliary police troops assisted in murdering Jews in Poland, Belarus and Ukraine.[294] One distinguished Lithuanian historian claims that there were five motivational factors eliciting participation in the atrocities by his countrymen. These were: (1) revenge against those who aided the Soviets; (2) expiation for those who wanted to demonstrate loyalty to the Nazis after collaborating previously with the Soviets; (3) antisemitism; (4) opportunism; and (5) self-enrichment.[295]

Netherlands

Known prior to the war for racial and religious tolerance, the Netherlands had taken in Jews since the 16th century, many of whom had found refuge there after fleeing Spain.[296] Before the German invasion of May 1940, approximately 140,000 Jews resided in the Netherlands, around 30,000 of them were refugees from Austria and Germany.[297] Nearly 60 percent of Dutch Jews lived in Amsterdam, constituting some 80,000 people.[298] Once the Nazis invaded, a host of antisemitic measures were enacted to include exclusion from professions like the civil service.[299] Anti-Jewish legislation that had taken years to institute in Germany was enacted within just months in the Netherlands.[300] On 22 October 1940, all Jewish banks and businesses had to register and all assets, whether private or those in banks, had to be declared.[301] Even radio sets in possession of Jews were forbidden and confiscated.[302] By January 1941, the Jews of the Netherlands were being defined by racist criteria, had to be registered, and merely a month later in February, many were being deported to Westerbork transit camp in the eastern part of the country. From there, most Dutch Jews were first sent to Mauthausen concentration camp.[302] While there was participation from some Dutch volunteers in various acts against the Jews, there was more of a tacit and begrudging acquiesance in the Netherlands, which required a very visible Nazi presence throughout the entire war to exploit the country's economic wealth and enforce Nazi occupation policies.[303][lower-alpha 19]

From the summer of 1942 forward, upwards of 102,000 Dutch Jews were deported and murdered—much of which was made possible by the "cooperation and efficiency of the Dutch civil service and police" who willingly served the Germans.[305] Not only was there relatively smooth cooperation between Dutch authorities and Dutch police, the SS and the Nazi police organizations in the Netherlands also worked well together there; additionally, volunteers from indigenous fascist organizations assisted in persecuting Jews, and the Jewish council in Amsterdam, unfortunately, spread undue optimism and as a result, very few Dutch Jews went into hiding.[306] In all fairness to the Jewish council, however, they were deceived and provided misinformation by the Nazi commissioner for Amsterdam, Hans Böhmcker.[307] Historians Deborah Dwork and Robert Jan van Pelt report that in the Netherlands, nearly 80% of the 140,000 Jews originally living there were murdered.[308][lower-alpha 20][lower-alpha 21]

Norway