Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is a Eurasian political, economic and security organization. It is the world's largest regional organization in terms of geographic scope and population, covering approximately 60% of the area of Eurasia, 40% of the world population, and more than 30% of global GDP.[3]

| Chinese: 上海合作组织 Russian: Шанхайская Организация Сотрудничества | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

Members Observers Dialogue partners | |

| Abbreviation | SCO |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Shanghai Five |

| Formation | 15 June 2001 |

| Type | Mutual security, political, and economic alliance |

| Headquarters | Beijing, China (Secretariat) Tashkent, Uzbekistan (RATS Executive Committee) |

Membership |

Observers Dialogue partners Guest attendees |

Official language | |

Secretary-General | Zhang Ming |

Deputy Secretaries-General |

|

RATS Executive Committee Director | Ruslan Mirzaev |

| Website | eng |

The SCO is the successor to the Shanghai Five, formed in 1996 between the People's Republic of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan.[4] On 15 June 2001, the leaders of these nations and Uzbekistan met in Shanghai to announce a new organization with deeper political and economic cooperation; the SCO Charter was signed on 7 July 2002 and entered into force on 19 September 2003. Its membership has since expanded to eight states, with India and Pakistan joining on 9 June 2017. Several countries are engaged as observers or dialogue partners.

The SCO is governed by the Heads of State Council (HSC), its supreme decision-making body, which meets once a year.

Origins

The Shanghai Five group was created on 26 April 1996 with the signing of the Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions in Shanghai by the heads of states of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan.[5]

On 24 April 1997 the same countries signed the Treaty on Reduction of Military Forces in Border Regions in a meeting in Moscow, Russia.[6] On 20 May 1997 Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Chinese Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin signed a declaration on a "multipolar world".[7]

Subsequent annual summits of the Shanghai Five group occurred in Almaty, Kazakhstan in 1998, in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in 1999, and in Dushanbe, Tajikistan in 2000. At the Dushanbe summit, members agreed to "oppose intervention in other countries' internal affairs on the pretexts of 'humanitarianism' and 'protecting human rights;' and support the efforts of one another in safeguarding the five countries' national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and social stability."[8]

In 2001, the annual summit returned to Shanghai. There the five member nations first admitted Uzbekistan in the Shanghai Five mechanism (thus transforming it into the Shanghai Six). Then all six heads of state signed on 15 June 2001 the Declaration of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, praising the role played thus far by the Shanghai Five mechanism and aiming to transform it to a higher level of cooperation.[2]

In June 2002, the heads of the SCO member states met in Saint Petersburg, Russia. There they signed the SCO Charter which expounded on the organisation's purposes, principles, structures and forms of operation, and established it in international law.

In July 2005, at the summit in Astana, Kazakhstan, with representatives of India, Iran, Mongolia and Pakistan attending an SCO summit for the first time, Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of the Kazakhstan, greeted the guests in words that had never been used before in any context: "The leaders of the states sitting at this negotiation table are representatives of half of humanity".[9]

By 2007 the SCO had initiated over twenty large-scale projects related to transportation, energy and telecommunications and held regular meetings of security, military, defence, foreign affairs, economic, cultural, banking, and other officials from its member states.[10]

In July 2015 in Ufa, Russia, the SCO decided to admit India and Pakistan as full members. Both signed the memorandum of obligations in June 2016 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, thereby starting the formal process of joining the SCO as full members.[11] On 9 June 2017, at a summit in Astana, India and Pakistan officially joined SCO as full members.

The SCO has established relations with the United Nations in 2004 (where it is an observer in the General Assembly), Commonwealth of Independent States in 2005, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2005, the Collective Security Treaty Organization in 2007, the Economic Cooperation Organization in 2007, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in 2011, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) in 2014, and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific in 2015.[12] SCO Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) has established relations with the African Union's African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT) in 2018.[13]

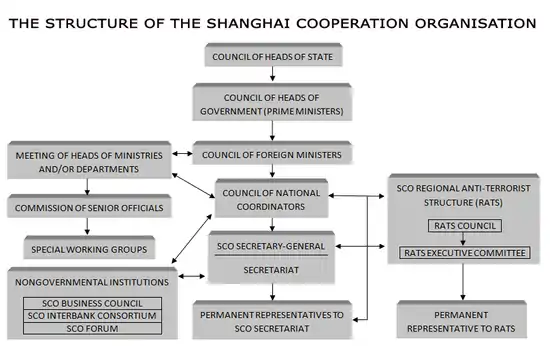

Organisational structure

The Council of Heads of State is the top decision-making body in the SCO. This council meets at the SCO summits, which are held each year in one of the member states' capital cities. Because of their government structure, the prime ministers of the parliamentary democracies of India and Pakistan attend the SCO Council of Heads of State summits, as their responsibilities are similar to the presidents of other SCO nations.[14] The current Council of Heads of State consists of:

- Xi Jinping (China)

- Narendra Modi (India)

- Kassym-Jomart Tokayev (Kazakhstan)

- Sadyr Japarov (Kyrgyzstan)

- Shehbaz Sharif (Pakistan)

- Vladimir Putin (Russia)

- Emomali Rahmon (Tajikistan)

- Shavkat Mirziyoyev (Uzbekistan)

The Council of Heads of Government is the second-highest council in the organisation. This council also holds annual summits, at which time members discuss issues of multilateral cooperation. The council also approves the organisation's budget. The current Council of Heads of Government consists of:

- Li Keqiang (China)

- Narendra Modi (India) (usually sends a deputy, such as EAM Subrahmanyam Jaishankar at the 2021 summit)[15]

- Alihan Smaiylov (Kazakhstan)

- Akylbek Japarov (Kyrgyzstan)

- Shehbaz Sharif (Pakistan) (usually sends a deputy, such as Parliamentary Secretary for Foreign Affairs Andleeb Abbas at the 2020 summit)[14]

- Mikhail Mishustin (Russia)

- Qohir Rasulzoda (Tajikistan)

- Abdulla Aripov (Uzbekistan)

The Council of Foreign Ministers also holds regular meetings, where they discuss the current international situation and the SCO's interaction with other international organisations.[16]

The Council of National Coordinators coordinates the multilateral cooperation of member states within the framework of the SCO's charter.[17]

The Secretariat of the SCO, headquartered in Beijing, China, is the primary executive body of the organisation. It serves to implement organisational decisions and decrees, drafts proposed documents (such as declarations and agendas), function as a document depository for the organisation, arranges specific activities within the SCO framework, and promotes and disseminates information about the SCO. The SCO Secretary-General is elected to a three-year term. The current Secretary-General is Zhang Ming of China, who assumed his office on 1 January 2022.

The Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) Executive Committee, headquartered in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, is a permanent organ of the SCO which serves to promote cooperation of member states against the three evils of terrorism, separatism and extremism. The Director of SCO RATS Executive Committee is elected to a three-year term. The current Director is Ruslan Mirzaev of Uzbekistan, who assumed his office on 1 January 2022. Each member state also sends a permanent representative to RATS.[18]

The official languages of the SCO are Chinese and Russian.[2]

Membership

Member states

.png.webp)

| Country | Accession started | Member since |

|---|---|---|

| — | 15 June 2001[lower-alpha 1] | |

| 10 June 2015 | 9 June 2017 | |

| Acceding members | ||

| 17 September 2021 | No earlier than April 2023 | |

| 16 September 2022 | TBA | |

Observer states

Afghanistan received observer status at the 2012 SCO summit in Beijing, China on 7 June 2012.[21] No country has yet provided diplomatic recognition to the Taliban, and its representatives have not participated in SCO meetings so far.[1] The Afghanistan head of state first attended the 2004 SCO summit as a guest attendee.

In 2008, Belarus applied for partner status in the organisation and was promised Kazakhstan's support towards that goal. However, Russian Defence Minister Sergei Ivanov voiced doubt on the probability of Belarus' membership, saying that Belarus was a purely European country.[23] Despite this, at the 2009 SCO Summit in Yekaterinburg a decision was made to grant Belarus the dialogue partner status, which it officially received on 28 April 2010. After applying in 2012 for the observer status, Belarus received it in 2015.[22] On 14 June 2022, Russia's Special Presidential Representative on SCO Affairs Bakhtiyor Khakimov confirmed that Belarus had applied for membership.[24]

Iran has been an observer state since 2005.[25] On 17 September 2021, the SCO launched the procedures of Iran's accession to the SCO, which are expected to take "a fair amount of time".[26][27][28] 15 September 2022, Iran signed an memorandum of obligations to join the SCO at the 2022 summit, and will join the organization subject to its parliament ratifying a number of agreements.[29][30]

Mongolia became the first country to receive observer status at the 2004 Tashkent Summit. Pakistan, India and Iran received observer status at the 2005 SCO summit in Astana, Kazakhstan on 5 July 2005.

Dialogue partners

The status of dialogue partner was created in 2008.[31]

| Country | Status approved | Status granted[lower-alpha 2] |

|---|---|---|

| 15 or 16 June 2009[32][33] | 6 May 2010[34] | |

| 7 June 2012[21] | 26 April 2013[35] | |

| 10 July 2015[36] | 24 September 2015[37] | |

| 14 March 2016[38] | ||

| 22 March 2016[39] | ||

| 16 April 2016[40] | ||

| 16 September 2021 | 14 September 2022[41][42] | |

| Upcoming dialogue partners[lower-alpha 3] | ||

| 16 September 2022 [43] | TBA | |

| Former dialogue partners | ||

| 15 or 16 June 2009 | 28 April 2010 | |

Guest attendances

Multiple international organisations and one country are guest attendances to SCO summits.

Future membership possibilities

In 2010, the SCO has approved a procedure for admitting new members.[44]

Mongolia and Afghanistan, which have observer status, have stated their intention to become full SCO members.[45]

In 2011, Turkey applied for dialogue partner status,[46] which it obtained in 2013.

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has stated that he has discussed the possibility of abandoning Turkey's candidacy of accession to the European Union in return for full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.[47] This was reinforced again on 21 November 2016, after the European Parliament voted unanimously to suspend accession negotiations with Turkey.[48] Two days later, on 23 November 2016, Turkey was granted the chairmanship of SCO energy club for the 2017 period. That made Turkey the first country to chair a club in the organisation without full membership status. In 2022, Erdogan announced that Turkey would seek full SCO membership status.[49]

In 2011, Vietnam expressed interest in obtaining observer status (but has not applied for it).[46]

In 2012, Ukraine expressed interest in obtaining observer status (but has not applied for it).[50][51]

In 2012, Bangladesh applied for observer status.[45]

In 2015, Syria applied for dialogue partner status.[lower-alpha 4][52][53]

In 2016, Israel applied for dialogue partner status.[52]

In 2019 or earlier, Iraq applied for dialogue partner status.[54]

Turkmenistan has previously declared itself a permanently neutral country, which was recognized by a resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, thus precluding its membership in the SCO.[55][56] Turkmenistan head of state has been attending SCO summits since 2007 as a guest attendee.

Activities

Cooperation on security

The SCO is primarily centered on security-related concerns, often describing the main threats it confronts as being terrorism, separatism and extremism.

At SCO summit, held in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, on 16–17 June 2004, the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) was established. On 21 April 2006, the SCO announced plans to fight cross-border drug crimes under the counter-terrorism rubric.[57]

In October 2007, the SCO signed an agreement with the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), in the Tajik capital of Dushanbe, to broaden cooperation on issues such as security, crime, and drug trafficking.[58]

The organisation is also redefining cyberwarfare, saying that the dissemination of information "harmful to the spiritual, moral and cultural spheres of other states" should be considered a "security threat". An accord adopted in 2009 defined "information war", in part, as an effort by a state to undermine another's "political, economic, and social systems".[59] The Diplomat reported in 2017 that SCO has foiled 600 terror plots and extradited 500 terrorists through RATS.[60] The 36th meeting of the Council of the RATS decided to hold a joint anti-terror exercise, Pabbi-Antiterror-2021, in Pakistan in 2021.[61]

Military activities

Over the past few years, the organisation's activities have expanded to include increased military cooperation, intelligence sharing, and counterterrorism.[62]

Military exercises are regularly conducted among members to promote cooperation and coordination against terrorism and other external threats, and to maintain regional peace and stability.[2] There have been a number of SCO joint military exercises. The first of these was held in 2003, with the first phase taking place in Kazakhstan and the second in China. Since then China and Russia have teamed up for large-scale war games in Peace Mission 2005, Peace Mission 2007 and Peace Mission 2009, under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. More than 4,000 soldiers participated at the joint military exercises in Peace Mission 2007, which took place in Chelyabinsk, Russia near the Ural Mountains, as was agreed upon in April 2006 at a meeting of SCO Defence Ministers.[63][64] Russian Defence Minister Sergei Ivanov said that the exercises would be transparent and open to media and the public. Following the war games' successful completion, Russian officials began speaking of India joining such exercises in the future and the SCO taking on a military role. Peace Mission 2010, conducted 9–25 September at Kazakhstan's Matybulak training area, saw over 5,000 personnel from China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan conduct joint planning and operational maneuvers.[65]

The SCO has served as a platform for larger military announcements by members. During the 2007 war games in Russia, with leaders of SCO member states in attendance including China's paramount leader Hu Jintao, Russia's President Vladimir Putin used the occasion to take advantage of a captive audience. Russian strategic bombers, he said, would resume regular long-range patrols for the first time since the Cold War. "Starting today, such tours of duty will be conducted regularly and on the strategic scale", Putin said. "Our pilots have been grounded for too long. They are happy to start a new life".

On 4 June 2014, in the Tajik capital Dushanbe, the idea was brought up to merge the SCO with the Collective Security Treaty Organization. It is still being debated.

At the same time, leaders of SCO states have repeatedly stated that the SCO is not a military alliance.[66]

Economic cooperation

Russia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are also members of the Eurasian Economic Union.

A Framework Agreement to enhance economic cooperation was signed by the SCO member states on 23 September 2003. At the same meeting the Premier of China, Wen Jiabao, proposed a long-term objective to establish a free trade area in the SCO, while other more immediate measures would be taken to improve the flow of goods in the region.[67][68] A follow up plan with 100 specific actions was signed one year later, on 23 September 2004.[69]

On 26 October 2005, during the Moscow Summit of the SCO, the Secretary General of the Organisation said that the SCO will prioritise joint energy projects; including in the oil and gas sector, the exploration of new hydrocarbon reserves, and joint use of water resources. The creation of the SCO Interbank Consortium was also agreed upon at that summit in order to fund future joint projects. The first meeting of the SCO Interbank Association was held in Beijing on 21–22 February 2006.[70][71] On 30 November 2006, at The SCO: Results and Perspectives, an international conference held in Almaty, the representative of the Russian Foreign Ministry announced that Russia is developing plans for an SCO "Energy Club".[72] The need for this "club" was reiterated by Moscow at an SCO summit in November 2007. Other SCO members, however, have not committed themselves to the idea.[73] However, during the 2008 summit it was stated that "Against the backdrop of a slowdown in the growth of world economy pursuing a responsible currency and financial policy, control over the capital flowing, ensuring food and energy security have been gaining special significance".[74]

At the 2007 SCO summit Iranian Vice President Parviz Davoodi addressed an initiative that had been garnering greater interest and assuming a heightened sense of urgency when he said, "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation is a good venue for designing a new banking system which is independent from international banking systems".[75]

The address by President Putin also included these comments:

We now clearly see the defectiveness of the monopoly in world finance and the policy of economic selfishness. To solve the current problem Russia will take part in changing the global financial structure so that it will be able to guarantee stability and prosperity in the world and to ensure progress.

The world is seeing the emergence of a qualitatively different geo-political situation, with the emergence of new centers of economic growth and political influence.

We will witness and take part in the transformation of the global and regional security and development architectures adapted to new realities of the 21st century, when stability and prosperity are becoming inseparable notions.[76]

On 16 June 2009, at the Yekaterinburg Summit, China announced plans to provide a US$10 billion loan to other SCO member states to shore up the struggling economies of its members amid the global financial crisis.[77] The summit was held together with the first BRIC summit, and the China–Russia joint statement said that they want a bigger quota in the International Monetary Fund.[78]

During 2019 Bishkek summit, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has suggested taking steps to trade in local currencies instead of U.S. dollars and setting up financial institutions including an SCO bank.[79]

In June 2022, Iran's Deputy Foreign Minister for Economic Diplomacy Mehdi Safari has suggested creating a single SCO currency to facilitate trade and financial transactions among SCO members.[80]

During 19–22 October 2022, Iran will host SCOCOEX, an international conference and exhibition on economic cooperation opportunities available to the SCO member states and partners.[81]

Cultural cooperation

Cultural cooperation also occurs in the SCO framework. Culture ministers of the SCO met for the first time in Beijing on 12 April 2002, signing a joint statement for continued cooperation. The third meeting of the Culture Ministers took place in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, on 27–28 April 2006.[82][83]

An SCO Arts Festival and Exhibition was held for the first time during the Astana Summit in 2005. Kazakhstan has also suggested an SCO folk dance festival to take place in 2008, in Astana.[84]

Summits

According to the Charter of the SCO, summits of the Council of Heads of State shall be held annually at alternating venues. The locations of these summits follow the alphabetical order of the member state's name in Russian.[85] The charter also dictates that the Council of Heads of Government (that is, the Prime Ministers) shall meet annually in a place decided upon by the council members. The Council of Foreign Ministers is supposed to hold a summit one month before the annual summit of Heads of State. Extraordinary meetings of the Council of Foreign Ministers can be called by any two member states.[85]

List of summits

| Date | Country | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 14–15 June 2001 | Shanghai | |

| 7 June 2002 | Saint Petersburg | |

| 29 May 2003 | Moscow | |

| 17 June 2004 | Tashkent | |

| 5 July 2005 | Astana | |

| 15 June 2006 | Shanghai | |

| 16 August 2007 | Bishkek | |

| 28 August 2008 | Dushanbe | |

| 15–16 June 2009 | Yekaterinburg | |

| 10–11 June 2010 | Tashkent[86] | |

| 14–15 June 2011 | Astana[87] | |

| 6–7 June 2012 | Beijing | |

| 13 September 2013 | Bishkek | |

| 11–12 September 2014 | Dushanbe | |

| 9–10 July 2015 | Ufa | |

| 23–24 June 2016 | Tashkent[88] | |

| 8–9 June 2017 | Astana | |

| 9–10 June 2018 | Qingdao | |

| 14–15 June 2019 | Bishkek[89] | |

| 10 November 2020 | videoconference[90] | |

| 16–17 September 2021 | Dushanbe[91] | |

| 15–16 September 2022 | Samarkand | |

| 2023 | New Delhi |

| Date | Country | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 14 September 2001 | Almaty | |

| — | — | — |

| 23 September 2003 | Beijing | |

| 23 September 2004 | Bishkek | |

| 26 October 2005 | Moscow | |

| 15 September 2006 | Dushanbe | |

| 2 November 2007 | Tashkent | |

| 30 October 2008 | Astana | |

| 14 October 2009 | Beijing[92] | |

| 25 November 2010 | Dushanbe[93] | |

| 7 November 2011 | Saint Petersburg | |

| 5 December 2012 | Bishkek[94] | |

| 29 November 2013 | Tashkent | |

| 14–15 December 2014 | Astana | |

| 14–15 December 2015 | Zhengzhou | |

| 2–3 November 2016 | Bishkek | |

| 30 November 2017 | Sochi | |

| 11–12 October 2018 | Dushanbe | |

| 1–2 November 2019 | Tashkent | |

| 30 November 2020 | videoconference | |

| 25 November 2021 | videoconference | |

| 1 November 2022 | videoconference |

Analysis

Relations with the West

The United States applied for observer status in the SCO, but was rejected in 2005.[95]

At the Astana summit in July 2005, with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq foreshadowing an indefinite presence of U.S. forces in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, the SCO requested the U.S. to set a clear timetable for withdrawing its troops from SCO member states. Shortly afterwards, Uzbekistan requested the U.S. to leave the K2 air base.[96]

A report in 2007 noted that the SCO has made no direct comments against the U.S. or its military presence in the region; however, some indirect statements at the past summits have been viewed by Western media outlets as "thinly veiled swipes at Washington".[97]

In 2015 a European Parliament researcher expressed her view that "institutional weaknesses, a lack of common financial funds for the implementation of joint projects and conflicting national interests have prevented the SCO from achieving a higher level of regional cooperation".[98]

Geopolitical aspects

There have been many discussions and commentaries about the geopolitical nature of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Matthew Brummer, in the Journal of International Affairs, tracks the implications of SCO expansion into the Persian Gulf.[99] Also, according to political scientist Thomas Ambrosio, one aim of SCO was to ensure that liberal democracy could not gain ground in these countries.[100]

Iranian writer Hamid Golpira had this to say on the topic: "According to Zbigniew Brzezinski's theory, control of the Eurasian landmass is the key to global domination and control of Central Asia is the key to control of the Eurasian landmass....Russia and China have been paying attention to Brzezinski's theory, since they formed the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2001, ostensibly to curb extremism in the region and enhance border security, but most probably with the real objective of counterbalancing the activities of the United States and the rest of the NATO alliance in Central Asia".[101]

At a 2005 summit in Kazakhstan the SCO issued a Declaration of Heads of Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation which addressed their "concerns" and contained an elaboration of the organisation's principles. It included: "The heads of the member states point out that, against the backdrop of a contradictory process of globalisation, multilateral cooperation, which is based on the principles of equal right and mutual respect, non-intervention in internal affairs of sovereign states, non-confrontational way of thinking and consecutive movement towards democratisation of international relations, contributes to overall peace and security, and call upon the international community, irrespective of its differences in ideology and social structure, to form a new concept of security based on mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality and interaction."[102]

In November 2005 Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov reiterated that the "Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is working to establish a rational and just world order" and that "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation provides us with a unique opportunity to take part in the process of forming a fundamentally new model of geopolitical integration".[103]

The People's Daily expressed the matter in these terms: "The Declaration points out that the SCO member countries have the ability and responsibility to safeguard the security of the Central Asian region, and calls on Western countries to leave Central Asia. That is the most noticeable signal given by the Summit to the world".[104]

Human rights issues

In the December 2015 United Nations General Assembly vote, all six members of the SCO voted against the overall human rights situation in Iran, expressing concern not only about religious persecution but also the government's frequent use of the death penalty, failure to uphold legal due process, restrictions on freedom of expression, and ongoing discrimination against women and ethnic minorities.[105]

In July 2019, five of the eight SCO members were among the 50 countries that backed China's policies in Xinjiang, signing a joint letter to the UNHRC commending China's "remarkable achievements in the field of human rights", claiming "Now safety and security has returned to Xinjiang and the fundamental human rights of people of all ethnic groups there are safeguarded.[106][107] By June 2020, four of the eight SCO members were among the 53 countries that backed the Hong Kong national security law at the United Nations.[108]

Current leaders of member states

See also

- Asia Cooperation Dialogue

- Asia–Europe Meeting

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Collective Security Treaty Organization

- Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Eurasianism

- China–Russia relations

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

Notes

- China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan were members of the Shanghai Five mechanism since 26 April 1996. Uzbekistan was included in the Shanghai Five mechanism on 14 June 2001.[19] The six states then signed a declaration establishing the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation on 15 June 2001.[20]

- A country officially becomes a SCO dialogue partner after its minister of foreign affairs and SCO Secretary-General sign a memorandum granting the status.

- These countries have not yet signed memorandums granting them the status of SCO dialogue partner, so they are not de jure dialogue partners yet. Historically, such memorandum has been signed within a year from an announcement that a country is approved as SCO dialogue partner.

- Syria has initially applied for observer status, but "it was explained that first it is necessary to become a dialogue partner of the organization".[52]

- The President of China is legally a ceremonial office, but the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (de facto top leader) has always held this office since 1993, except for the months of transition. The current paramount leader is Xi Jinping.

References

- Seiwert, Eva (30 September 2021). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organization Will Not Fill Any Vacuum in Afghanistan". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

So far, the SCO has not officially recognized the Taliban regime and did not invite its representatives to the summit in Dushanbe in mid-September.

- "About SCO". Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "Iran looks east after China-led bloc OKs entry". France 24. 18 September 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- "Shanghai Five: An Attempt to Counter U.S. Influence in Asia?". Brookings. 4 May 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "The Shanghai Cooperation Organization". Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Al-Qahtani, Mutlaq (2006). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Law of International Organizations". Chinese Journal of International Law. Oxford University Press. 5 (1): 130. doi:10.1093/chinesejil/jml012. ISSN 1540-1650.

- "Russian-Chinese Joint Declaration on a Multipolar World and the Establishment of a New International Order". United Nations General Assembly. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017.

- Gill (30 November 2001). "Shanghai Five: An Attempt to Counter U.S. Influence in Asia?". Brookings. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Kazinform, 5 July 2005.

- Agostinis, Giovanni; Urdinez, Francisco (20 October 2021). "The Nexus between Authoritarian and Environmental Regionalism: An Analysis of China's Driving Role in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization". Problems of Post-Communism: 1–15. doi:10.1080/10758216.2021.1974887. ISSN 1075-8216. S2CID 239486136.

- "India, Pakistan edge closer to joining SCO security bloc". Agence France-Presse. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016 – via The Express Tribune.

- "External communication". Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "AU, SCO anti-terror organs sign cooperation deal on fighting terrorism". Times of Islamabad. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Haidar, Suhasani (28 November 2020). "India to host SCO Heads of Government meet; Modi, Imran to skip". The Hindu. THG PUBLISHING PVT LTD. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- "EAM S Jaishankar to represent India at SCO heads of govt meeting". 25 November 2021.

- "Session of the Council of Foreign Ministers from Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation" (Press release). Kuala Lumpur: Embassy of the Russian Federation in Malaysia. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (29 January 2021). "The First SCO Council of National Coordinators Meeting Chaired by Tajikistan". mfa.tj. Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- "Information on Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008.

- Совместное заявление глав государств Республики Казахстан, Китайской Народной Республики, Кыргызской Республики, Российской Федерации, Республики Таджикистан, Республики Узбекистан [Joint statement of heads of state of Republic of Kazakhstan, People's Republic of China, Kyrgyz Republic, Russian Federation, Republic of Tajikistan, Republic of Uzbekistan]. President of Russia (in Russian). 14 June 2001.

- Главы государств «Шанхайского форума» приняли Декларацию о создании нового объединения – Шанхайской организации сотрудничества ["Shanghai Forum" heads of state have adopted the Declaration on creation of a new association – the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation]. President of Russia (in Russian). 15 June 2001.

- "SCO accepts Afghanistan as observer, Turkey dialogue partner". Xinhua News Agency. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012 – via People's Daily.

- "Belarus gets observer status in Shanghai Cooperation Organization". Belarusian Telegraph Agency. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Lantratov, Konstantin; Orozaliev, Bek; Zygar, Mikhail; Safronov, Ivan (27 April 2006). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation acquires military character". Kommersant. No. 75. p. 9. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016.

- "Belarus prepares bid to join SCO - Russian presidential envoy". Interfax. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "What Iran's membership of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation means". Al Jazeera. 19 September 2021.

- "News Analysis: Why is Iran keen on full SCO membership?". Xinhua. 18 September 2021.

- "Iran Joins SCO". Financial Tribune. 17 September 2021.

- "A new step towards Iran joining the SCO as a member state". Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

- "Iran signs memorandum to join Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "Iran has joined Shanghai Cooperation Organization". akipress.com. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "Regulations on the Status of Dialogue Partner of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Sri Lanka gains partnership in SCO members welcome end to terror in country". Ministry of Defence, Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. 30 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Bedi, Rahul (2 June 2007). "Sri Lanka turns to Pakistan, China for military needs". IANS. Urdustan.com Network. Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- "Russian MFA Spokesman Andrei Nesterenko Response to Media Question about the Signing of a Memorandum Granting the Status of SCO Dialogue Partner to Sri Lanka". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia). 12 May 2010.

- "No: 123, 26 April 2013, Press Release Concerning the Signing of a Memorandum with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Turkey). 26 April 2013.

- Kucera, Joshua (10 July 2015). "SCO Summit Provides Few Concrete Results, But More Ambitious Goals". Eurasianet. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Cambodia becomes dialogue partner in SCO". TASS. 24 September 2015.

- "Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov met with Rashid Alimov, Secretary General of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization within his working visit to the People's Republic of China". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Azerbaijan). 14 March 2016.

- "Press Release issued by Embassy of Nepal, Beijing on Nepal officially joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as a dialogue partner". Government of Nepal – Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Armenia was granted a status of dialogue partner in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Armenia). 16 April 2016.

- "SCO member states signed memorandums on granting SCO dialogue partner status to the Arab Republic of Egypt and the State of Qatar". Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "President Xi Jinping Attends the 22nd Meeting of the SCO Council of Heads of State and Delivers Important Remarks". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "President Xi Jinping Attends the 22nd Meeting of the SCO Council of Heads of State and Delivers Important Remarks". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PRC. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- Wu, Jiao; Li, Xiaokun (12 June 2010). "SCO agrees deal to expand". China Daily. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- Moskovskij Komsomolets (15 September 2012). "Azerbaijan asks to join a new alliance of China and Russia". Azeri Daily. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Radyuhin, Vladimir (2 December 2011). "Vietnam bids to join SCO". The Hindu. Moscow. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Dalay, Galip (14 May 2013). "Turkey between Shanghai and Brussels". The New Turkey. Translated by Öz, Handan. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- Butler, Daren (21 November 2016). "Fed up with EU, Erdogan says Turkey could join Shanghai Group". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "Turkey Seeks to Be First NATO Member to Join China-Led SCO". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- "Yanukovych Tells Putin Kyiv Wants SCO Observer Status". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Grigoryan, Gurgen (8 October 2012). "Why Ukraine wants to become SCO's partner". InfoSCO. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Syria, Israel, Egypt willing to join SCO's activity – president's special envoy". Interfax. 23 June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Egypt applies to become dialogue partner of Shanghai security bloc – Kremlin aide". TASS. 6 July 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "'SCO family' widening? Many candidates share 'Shanghai spirit', but expansion not a goal". TASS. 5 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- United Nations General Assembly Session 90 Resolution 50/80. Maintenance of international security A/RES/50/80 12 December 1995. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Shubham (7 June 2018). "SCO Summit 2018: Why Turkmenistan is not part of the Eurasia security bloc". oneindia.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Luan, Shanglin, ed. (22 April 2006). "SCO to intensify fight against cross-border drug crimes". Beijing. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Security alliances led by Russia, China link up". Business Recorder. Dushanbe. 6 October 2007. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Gjelten, Tom (23 September 2010). "Seeing The Internet As An 'Information Weapon'". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Desai, Suyash (5 December 2017). "India's SCO Challenge". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- PTI (21 March 2021). "India, Pakistan, China to participate in SCO joint anti-terrorism exercise". ThePrint. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Scheineson, Andrew (24 March 2009). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organization". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Hutzler, Charles (26 April 2006). "China, Russia, Others to Hold Joint Drills". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- Yu, Bin (17 October 2007). "Common exercise, different goals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Boland, Julie (29 October 2010), Learning From The Shanghai Cooperation Organization's 'Peace Mission-2010' Exercise", The Brookings Institution, archived from the original on 28 June 2011

- Tugsbilguun, Tumurkhuleg (2008–2009). "Does the Shanghai Cooperation Represent an Example of a Military Alliance?". The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs. 15–16: 59–107. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

In contrast, the political leaders and most analysts in the SCO member states, especially those in its two most influential members, Russia and China, have repeatedly emphasized that the SCO is not a military alliance, since it is not directed against a third party and is only interested in combating threats posed by terrorism, separatism and extremism.

- Kyodo News (23 September 2003). "LEAD: Central Asian powers agree to pursue free-trade zone". Beijing: Kyodo News International, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "China Intensifies Regional Trade Talks". Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD)

- China Foreign Ministry (23 September 2004). "Joint Communique of the Council of the Governmental Heads (Prime Ministers) of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Member States" (Press release). Archived from the original on 30 March 2009.

- Blagov, Sergei (31 October 2005). "Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Eyes Economic, Security Cooperation". Eurasia Daily Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007.

- "SCO Ministers of Foreign Economic Activity and Trade to meet in Tashkent". National Bank of Uzbekistan. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011.

- "Russia's Foreign Ministry develops concept of SCO Energy Club". Kazakhstan Today. Almaty, Kazakhstan: Gazeta.kz Internet Agency. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Blagov, Sergei (6 November 2007). "Russia Urges Formation of Central Asian Energy Club". Eurasianet. The Open Society Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Chronicle of Main Events of 'Shanghai Five' and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008.

- Mehr News Agency, 31 October 2008.

- Russia Today, 30 October 2008

- Deng, Shasha, ed. (16 June 2009). "China to provide 10-billion-dollar loan to SCO members". Yekaterinburg, Russia. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Yan, ed. (18 June 2009). "China, Russia sign five-point joint statement". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

They also said that a new round of the IMF quota formula review and the reform schemes of the World Bank should be completed on time and that the emerging markets and developing countries should have a bigger say and broader representation in the international financial institutions.

- "Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit kicks off in Bishkek". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- پیشنهاد ایران به سازمان شانگهای برای ایجاد پول واحد [Iran's proposal to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to create a single currency]. TABNAK (in Persian). 2 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- "SCOCOEX Event in Iran Deferred to October". Tasnim. 21 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- "Culture Ministers of SCO Member States Meet in Beijing". People's Daily. People's Daily Online. 13 April 2002. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "SCO Culture Ministers to Meet in Tashkent". Kazakhstan Today. Almaty, Kazakhstan: Gazeta.kz Internet Agency. 17 April 2006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009.

- "Kazakhstan Backs Promotion of SCO Cultural Ties". KazInform. KazInform International News Agency. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- "Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014.

- "Joint Communiqué of Meeting of the Council of the Heads of the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014.

- Tang, Danlu, ed. (11 June 2010). "SCO vows to strengthen cooperation with its observers, dialogue partners". Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- Song Miou (10 July 2015). "Uzbekistan to host 16th SCO summit in 2016". Ufa, Russia. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Kyrgyzstan to host SCO summit in June 2019". AKIpress News Agency. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "Заседание Совета глав государств – членов ШОС". Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "PM to attend SCO head of states meeting in Dushanbe". 26 August 2021.

- Ho, Stephanie (14 October 2009). "Shanghai Cooperation Organization Summit Concludes in Beijing". Beijing: Voice of America. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Wen arrives in Tajikistan for SCO meeting". China Daily. Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Xinhua News Agency. 25 November 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "SCO Meeting Expected to Boost Cooperation Among Members". The Gazette of Central Asia. Satrapia. 2 December 2012.

- Hiro, Dilip (16 June 2006). "Shanghai surprise: The summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation reveals how power is shifting in the world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Varadarajan, Siddharth (8 July 2005). "Central Asia: China and Russia up the ante". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Kucera, Joshua (19 August 2007). "Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summiteers Take Shots at US Presence in Central Asia". Eurasianet. The Open Society Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- Grieger, Gisela (26 June 2015). "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation" (PDF). European Parliament Think Tank. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Journal of International Affairs. 2007. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and Iran: A Power-full Union. Matthew Brummer

- Ambrosio (October 2008). "Catching the 'Shanghai Spirit': How the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Promotes Authoritarian Norms in Central Asia". Europe-Asia Studies. 60 (8): 1321–1344. doi:10.1080/09668130802292143. S2CID 153557248.

- Golpira, Hamid (20 November 2008). "Iraq smoke screen". Tehran Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". 13 July 2005. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014.

- UzReport, 28 November 2005

- People's Daily Online (8 July 2008), "Opinion: SCO sends strong signals for West to leave Central Asia", People's Daily, archived from the original on 9 August 2016, retrieved 11 June 2016

- "Ongoing human rights violations in Iran spotlighted in UN vote". 17 December 2015.

- "Who cares about the Uyghurs". The Economist.

- "Letter to UNHRC". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Lawler, Dave (2 July 2020). "The 53 countries supporting China's crackdown on Hong Kong". Axios. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

Further reading

- Adıbelli, Barış (2006). "Greater Eurasia Project". Istanbul: IQ Publishing House.

- Adıbelli, Barış (2007). Turkey–China Relations since the Ottoman Period. Istanbul: IQ Publishing House.

- Adıbelli, Barış (2007). The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Dream of Turkey. Istanbul: Cumhuriyet Strateji.

- Adıbelli, Barış (2007). The Eurasia Strategy of China. Istanbul: IQ Publishing House.

- Adıbelli, Barış (2008). The Great Game in Eurasian Geopolitics. Istanbul: IQ Publishing House.

- Chabal, Pierre (2019), La coopération de Shanghai : conceptualiser la nouvelle Asie, Presses de l'Université de Liège, 308 p; 2019 – Presses Universitaires de Liège – La coopération de Shanghai

- Chabal, Pierre (2016), L'Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai et la construction de "la nouvelle Asie", Brussels: Peter Lang, 492 p.

- Chabal, Pierre (2015), Concurrences Interrégionales Europe-Asie au 21ème siècle, Brussels: Peter Lang, 388 p.

- Cohen, Dr. Ariel. (18 July 2001). "The Russia-China Friendship and Cooperation Treaty: A Strategic Shift in Eurasia?". The Heritage Foundation.

- Cohen, Dr. Ariel. (24 October 2005). "Competition over Eurasia: Are the U.S. and Russia on a Collision Course?". The Heritage Foundation.

- Colson, Charles. (5 August 2003). "Central Asia: Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Makes Military Debut". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Daly, John. (19 July 2001). "'Shanghai Five' expands to combat Islamic radicals". Jane's Terrorism & Security Monitor.

- Douglas, John Keefer; Matthew B. Nelson, and Kevin Schwartz; ""Fueling the Dragon's Flame: How China's Energy Demands Affect its Relationships in the Middle East"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2012. (162 KiB), United States–China Economic and Security Review Commission, October 2006.

- Fels, Enrico (2009), Assessing Eurasia's Powerhouse. An Inquiry into the Nature of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, Winkler Verlag: Bochum. ISBN 978-3-89911-107-1

- Gill, Bates and Oresman, Matthew, China's New Journey to the West: Report on China's Emergence in Central Asia and Implications for U.S. Interests, CSIS Press, August 2003

- Kalra, Prajakti and Saxena, Siddharth "Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and Prospects of Development in Eurasia Region" Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol 6. No. 2, 2007

- Plater-Zyberk, Henry; Monaghan, Andrew (2014). Strategic Implications of the Evolving Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press.

- Oresman, Matthew, "Beyond the Battle of Talas: China's Re-emergence in Central Asia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010. (4.74 MiB), National Defence University Press, August 2004

- Sznajder, Ariel Pablo, "China's Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Strategy", University of California Press, May 2006

- Yom, Sean L. (2002). "Power Politics in Central Asia: The Future of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Harvard Asia Quarterly 6 (4) 48–54.

_1.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_2.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)