Shavuot

Shavuot (![]() listen ), or Shavuos (

listen ), or Shavuos (![]() listen ) in some Ashkenazi usage (Hebrew: שָׁבוּעוֹת, Šāḇūʿōṯ, lit. "Weeks"), commonly known in English as the Feast of Weeks, is a Jewish holiday that occurs on the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Sivan (in the 21st century, it may fall between May 15 and June 14 on the Gregorian calendar). In the Bible, Shavuot marked the wheat harvest in the Land of Israel (Exodus 34:22). In addition, Orthodox rabbinic traditions teach that the date also marks the revelation of the Torah to Moses and the Israelites at Mount Sinai, which, according to the tradition of Orthodox Judaism, occurred at this date in 1314 BCE.[2]

listen ) in some Ashkenazi usage (Hebrew: שָׁבוּעוֹת, Šāḇūʿōṯ, lit. "Weeks"), commonly known in English as the Feast of Weeks, is a Jewish holiday that occurs on the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Sivan (in the 21st century, it may fall between May 15 and June 14 on the Gregorian calendar). In the Bible, Shavuot marked the wheat harvest in the Land of Israel (Exodus 34:22). In addition, Orthodox rabbinic traditions teach that the date also marks the revelation of the Torah to Moses and the Israelites at Mount Sinai, which, according to the tradition of Orthodox Judaism, occurred at this date in 1314 BCE.[2]

| Shavuоt | |

|---|---|

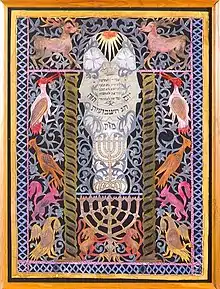

_(Das_Wochen-_oder_Pfingst-Fest)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Shavuot by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim | |

| Official name | Hebrew: שבועות or חג השבועות (Ḥag HaShavuot or Shavuos) |

| Also called | English: "Feast of Weeks" |

| Observed by | Jews and Samaritans |

| Type | Jewish and Samaritan |

| Significance | One of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. Celebrates the revelation of the Five Books of the Torah by God to Moses and to the Israelites at Mount Sinai, 49 days (seven weeks) after the Exodus from ancient Egypt. Commemorates the wheat harvesting in the Land of Israel. Culmination of the 49 days of the Counting of the Omer. |

| Celebrations | Festive meals. All-night Torah study. Recital of Akdamut liturgical poem in Ashkenazic synagogues. Reading of the Book of Ruth. Eating of dairy products. Decoration of homes and synagogues with greenery (Orach Chayim, 494). |

| Begins | 6th day of Sivan (or the Sunday following the 6th day of Sivan in Karaite Judaism) |

| Ends | 7th (in Israel: 6th) day of Sivan |

| Date | 6 Sivan |

| 2021 date | Sunset, 16 May – nightfall, 18 May[1] |

| 2022 date | Sunset, 4 June – nightfall, 6 June[1] |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 25 May – nightfall, 27 May[1] |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 11 June – nightfall, 13 June[1] |

| Related to | Passover, which precedes Shavuot |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

|

The word Shavuot means "weeks", and it marks the conclusion of the Counting of the Omer. Its date is directly linked to that of Passover; the Torah mandates the seven-week Counting of the Omer, beginning on the second day of Passover, to be immediately followed by Shavuot. This counting of days and weeks is understood to express anticipation and desire for the giving of the Torah. On Passover, the people of Israel were freed from their enslavement to Pharaoh; on Shavuot, they were given the Torah and became a nation committed to serving God.[3]

While it is sometimes referred to as Pentecost (in Koinē Greek: Πεντηκοστή) due to its timing after Passover, "pentecost" meaning "fifty" in Greek, since Shavuot occurs fifty days after the first day of Passover, it is not the same as the Christian Pentecost.[4][Note 1][5]

One of the biblically ordained Three Pilgrimage Festivals, Shavuot is traditionally celebrated in Israel for one day, where it is a public holiday, and for two days in the diaspora.[6][7][8]

Significance

Agricultural (wheat harvest)

Shavuot is not explicitly named in the Bible as the day on which the Torah was revealed by God to the Israelite nation at Mount Sinai, although this is commonly considered to be its main significance.[9][10]

What is textually connected in the Bible to the Feast of Shavuot is the season of the grain harvest, specifically of the wheat, in the Land of Israel. In ancient times, the grain harvest lasted seven weeks and was a season of gladness (Jer. 5:24, Deut. 16:9–11, Isa. 9:2). It began with the harvesting of the barley during Passover and ended with the harvesting of the wheat at Shavuot. Shavuot was thus the concluding festival of the grain harvest, just as the eighth day of Sukkot (Tabernacles) was the concluding festival of the fruit harvest. During the existence of the Temple in Jerusalem, an offering of two loaves of bread from the wheat harvest was made on Shavuot according to the commandment in Lev. 23:17.[5]

The last but one Qumran Scroll to be published has been discovered to contain two festival dates observed by the Qumran sect as part of their formally perfect 364-day calendar, and dedicated to "New Wine" and "New Oil", neither of which is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, but were known from another Qumran manuscript, the Temple Scroll. These festivals "constituted an extension of the festival of Shavuot ... which celebrates the New Wheat." All three festivals are calculated starting from the first Sabbath following Passover, by repeatedly adding exactly fifty days each time: first came New Wheat (Shavuot), then New Wine, and then New Oil.[11][12] (See also below, at "The Book of Jubilees and the Essenes".)

Names in the Torah

In the Bible, Shavuot is called the "Festival of Weeks" (Hebrew: חג השבועות, Chag HaShavuot, Exodus 34:22, Deuteronomy 16:10); "Festival of Reaping" (חג הקציר, Chag HaKatzir, Exodus 23:16),[13] and "Day of the First Fruits" (יום הבכורים, Yom HaBikkurim, Numbers 28:26).[14]

Shavuot, the plural of a word meaning "week" or "seven", alludes to the fact that this festival happens exactly seven weeks (i.e. "a week of weeks") after Passover.[15]

In the Talmud

The Talmud refers to Shavuot as ʻAṣeret (Hebrew: עצרת,[16] "refraining" or "holding back"),[17] referring to the prohibition against work on this holiday[17] and also to the conclusion of the Passover holiday-season.[18] The other reason given for the reference ʻAṣeret is that just as Shemini ʻAṣeret brings the Festival of Succoth to a "close", in the same respect, Shavuot (ʻAṣeret) brings The Festival of Passover to its actual "close". Since Shavuot occurs fifty days after Passover, Hellenistic Jews gave it the name "Pentecost" (Koinē Greek: Πεντηκοστή, "fiftieth day").[19]

Ancient observances

Ceremony of First Fruits, Bikkurim

Shavuot was also the first day on which individuals could bring the Bikkurim (first fruits) to the Temple in Jerusalem (Mishnah Bikkurim 1:3). The Bikkurim were brought from the Seven Species for which the Land of Israel is praised: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates (Deuteronomy 8:8).[19]

In the largely agrarian society of ancient Israel, Jewish farmers would tie a reed around the first ripening fruits from each of these species in their fields. At the time of harvest, the fruits identified by the reed would be cut and placed in baskets woven of gold and silver. The baskets would then be loaded on oxen whose horns were gilded and laced with garlands of flowers, and who were led in a grand procession to Jerusalem. As the farmer and his entourage passed through cities and towns, they would be accompanied by music and parades.[20]

Temple in Jerusalem

At the Temple in Jerusalem, each farmer would present his Bikkurim to a Kohen in a ceremony that followed the text of Deut. 26:1–10.

This text begins by stating: "An Aramean tried to destroy my father," referring to Laban's efforts to weaken Jacob and rob him of his progeny (Targum Onkelos and Rashi on Deut. 26:5) – or by an alternate translation, the text states "My father was a wandering Aramean," referring to the fact that Jacob was a penniless wanderer in the land of Aram for twenty years (Abraham ibn Ezra on Deut. 26:5).

The text proceeds to retell the history of the Jewish people as they went into exile in Ancient Egypt and were enslaved and oppressed; following which God redeemed them and brought them to the land of Israel.

The ceremony of Bikkurim conveys gratitude to God both for the first fruits of the field and for His guidance throughout Jewish history (Scherman, page 1068).

Modern religious observances

Nowadays in the post-Temple era, Shavuot is the only biblically ordained holiday that has no specific laws attached to it other than usual festival requirements of abstaining from creative work. The rabbinic observances for the holiday include reciting additional prayers, making kiddush, partaking of meals and being in a state of joy. There are however many customs which are observed on Shavuot.[21] A mnemonic for the customs largely observed in Ashkenazi communities spells the Hebrew word aḥarit (אחרית, "last"):

- אקדמות – Aqdamut, the reading of a piyyut (liturgical poem) during Shavuot morning synagogue services

- חלב – ḥalav (milk), the consumption of dairy products like milk and cheese

- רות – Rut, the reading of the Book of Ruth at morning services (outside Israel: on the second day)

- ירק – Yereq (greening), the decoration of homes and synagogues with greenery

- תורה – Torah, engaging in all-night Torah study.

The yahrzeit of King David is traditionally observed on Shavuot. Hasidic Jews also observe the yahrzeit of the Baal Shem Tov.[22]

Aqdamut

The Aqdamut (Imperial Aramaic: אקדמות) is a liturgical poem recited by Ashkenazi Jews extolling the greatness of God, the Torah, and Israel that is read publicly in Ashkenazic synagogues in the middle or – or in some communities right before – the morning reading of the Torah on the first day of Shavuot. It was composed by Rabbi Meir of Worms. Rabbi Meir was forced to defend the Torah and his Jewish faith in a debate with local priests and successfully conveyed his certainty of God's power, His love for the Jewish people, and the excellence of Torah. Afterwards he wrote the Aqdamut, a 90-line poem in Aramaic that stresses these themes. The poem is written in a double acrostic pattern according to the order of the Hebrew alphabet. In addition, each line ends with the syllable ta (תא), the last and first letters of the Hebrew alphabet, alluding to the endlessness of Torah. The traditional melodies that accompanies this poem also conveys a sense of grandeur and triumph.[23]

Azharot

There is an ancient tradition to recite poems known as Azharot listing the commandments. This was already considered a well-established custom in the 9th century.[24] These piyyutim were originally recited during the chazzan's repetition of the Mussaf amidah, in some communities they were later moved to a different part of the service.

Some Ashkenazic communities maintain the original practice of reciting the Azharot during musaf; they recite "Ata hinchlata" on the first day and "Azharat Reishit" on the second, both from the early Geonic period. Italian Jews do the same except that they switch the piyyutim of the two day, and in recent centuries, "Ata hinchlata" has been truncated to include only one 22-line poem instead of eight. Many Sephardic Jews recite the Azharot of Solomon ibn Gabirol before the mincha service; in many communities, the positive commandments are recited on the first day and the negative commandments on the second day.

Yatziv Pitgam

The liturgical poem Yatziv Pitgam (Imperial Aramaic: יציב פתגם) is recited by some synagogues in the diaspora on the second day of Shavuot. The author signs his name at the beginning of the poem's 15 lines – Yaakov ben Meir Levi, better knows as Rabbeinu Tam.[25]

Dairy foods

Dairy foods such as cheesecake, cheese blintzes,[26] and cheese kreplach among Ashkenazi Jews;[27] cheese sambusak,[28] kelsonnes (cheese ravioli),[29] and atayef (a cheese-filled pancake)[30] among Syrian Jews; kahee (a dough that is buttered and sugared) among Iraqi Jews;[30] and a seven-layer cake called siete cielos (seven heavens) among Tunisian and Moroccan Jews[30][31] are traditionally consumed on the Shavuot holiday. Yemenite Jews do not eat dairy foods on Shavuot.[30]

In keeping with the observance of other Jewish holidays, there is both a night meal and a day meal on Shavuot. Meat is usually served at night and dairy is served either for the day meal[27] or for a morning kiddush.[32]

Among the explanations given in rabbinic literature for the consumption of dairy foods on this holiday are:[33][34]

- Before they received the Torah, the Israelites were not obligated to follow its laws, which include shechita (ritual slaughter of animals) and kashrut. Since all their meat pots and dishes now had to be made kosher before use, they opted to eat dairy foods.

- The Torah is compared to milk by King Solomon, who wrote: "Like honey and milk, it lies under your tongue" (Song of Songs 4:11).

- The gematria of the Hebrew word ḥalav (חלב) is 40, corresponding to the forty days and forty nights that Moses spent on Mount Sinai before bringing down the Torah.

- According to the Zohar, each day of the year correlates to one of the Torah's 365 negative commandments. Shavuot corresponds to the commandment "Bring the first fruits of your land to the house of God your Lord; do not cook a kid in its mother's milk" (Exodus 34:26). Since the first day to bring Bikkurim (the first fruits) is Shavuot, the second half of the verse refers to the custom to eat two separate meals – one milk, one meat – on Shavuot.

- The Psalms call Mount Sinai Har Gavnunim (הר גבננים, mountain of majestic peaks, Psalm 68:16–17/15–16 ), which is etymologically similar to gevinah (גבינה, cheese).

Book of Ruth

There are five books in Tanakh that are known as Megillot (Hebrew: מגילות, "scrolls") and are publicly read in the synagogues of some Jewish communities on different Jewish holidays.[35] The Book of Ruth (מגילת רות, Megillat Ruth) is read on Shavuot because:

- King David, Ruth's descendant, was born and died on Shavuot (Jerusalem Talmud Hagigah 2:3);

- Shavuot is harvest time [Exodus 23:16], and the events of Book of Ruth occur at harvest time;

- The gematria (numerical value) of Ruth is 606, the number of commandments given at Sinai in addition to the Seven Laws of Noah already given, for a total of 613;

- Because Shavuot is traditionally cited as the day of the giving of the Torah, the entry of the entire Jewish people into the covenant of the Torah is a major theme of the day. Ruth's conversion to Judaism, and consequent entry into that covenant, is described in the book. This theme accordingly resonates with other themes of the day;

- Another central theme of the book is ḥesed (loving-kindness), a major theme of the Torah.[36]

Greenery

According to the Midrash, Mount Sinai suddenly blossomed with Flowers in anticipation of the giving of the Torah on its summit. It is for this reason that, in fact, Persian Jews refer to the Holiday of Shavuot by an entirely different name, namely, "The Mo'ed of Flowers" (موعد گل) in Persian (their daily language), and never as the Hebrew word "Shavuot" (which means "weeks").

Shavuot is one of the three Mo'edim ("appointed times") in the five Books of Moses: The Mo'ed (מועד) of the first month [Nisan], (i.e. Passover), The Mo'ed of Weeks [Flowers], (i.e. Shavuot), and The Mo'ed of Sukkah (i.e., Succot). The conglomerate name for these three "Pilgrimage Festivals" amongst All Jewish communities the world over is "Shalosh Regalim" (שלוש רגלים), literally "the Three Legs" because in ancient times the way people traveled to the "appointed place" (Jerusalem) at the "appointed time" (Mo'ed) was by walking there with their "legs" (regelim). This idea is translated into English as a "pilgrimage". The text of the Kiddush recited over wine is therefore identical, except for the reference to the particular celebration.

For this reason, many Jewish families traditionally decorate their homes and synagogues with plants, flowers and leafy branches in remembrance of the "sprouting of Mount Sinai" on the day of the Giving of the Torah, namely the seeing and hearing of the 10 Commandments.[37] Some synagogues decorate the bimah with a canopy of flowers and plants so that it resembles a chuppah, as Shavuot is mystically referred to as the day the matchmaker (Moses) brought the bride (the nation of Israel) to the chuppah (Mount Sinai) to marry the bridegroom (God); the ketubah (marriage contract) was the Torah. Some Eastern Sephardi communities read out a ketubah between God and Israel, composed by Rabbi Israel ben Moses Najara as part of the service. This custom was also adopted by some Hasidic communities, particularly from Hungary.[38]

The Vilna Gaon cancelled the tradition of decorating with trees because it too closely resembles the Christian decorations for their holidays.[39]

Greenery also figures in the story of the baby Moses being found among the bulrushes in a watertight cradle (Ex. 2:3) when he was three months old (Moses was born on 7 Adar and placed in the Nile River on 6 Sivan, the same day he later brought the Jewish nation to Mount Sinai to receive the Torah).[40]

All-night Torah study

The practice of staying up all Shavuot night to study Torah – known as Tiqun Leyl Shavuot (Hebrew: תקון ליל שבועות) ("Rectification for Shavuot Night") – is linked to a Midrash which relates that the night before the Torah was given, the Israelites retired early to be well-rested for the momentous day ahead. They overslept and Moses had to wake them up because God was already waiting on the mountaintop.[41] To rectify this perceived flaw in the national character, many religious Jews stay up all night to learn Torah.[42]

The custom of all-night Torah study goes back to 1533 when Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, then living in Ottoman Salonika, invited Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz and other Kabbalistic colleagues to hold Shavuot-night study vigils for which they prepared for three days in advance, just as the Israelites had prepared for three days before the giving of the Torah. During one of those study sessions, an angel appeared and taught them Jewish law.[43][44][45]

It has been suggested that the introduction of coffee (containing caffeine) throughout the Ottoman empire may have attributed to the "feasibility and popularity" of the practice of all-night Torah study.[46][47] In contrast, the custom of Yemenite Jews is to ingest the fresh leaves of a stimulant herb called Khat (containing cathinone) for the all-night ritual, an herb commonly used in that region of the world.

Any subject may be studied on Shavuot night, although Talmud, Mishnah, and Torah typically top the list. People may learn alone or with a chavruta (study partner), or attend late-night shiurim (lectures) and study groups.[48] In keeping with the custom of engaging in all-night Torah study, leading 16th-century kabbalist Isaac Luria arranged a recital consisting of excerpts from the beginning and end of each of the 24 books of Tanakh (including the reading in full of several key sections such as the account of the days of creation, the Exodus, the giving of the Ten Commandments and the Shema) and the 63 tractates of Mishnah,[49][50] followed by the reading of Sefer Yetzirah, the 613 commandments as enumerated by Maimonides, and excerpts from the Zohar, with opening and concluding prayers. The whole reading is divided into thirteen parts, after each of which a Kaddish d-Rabbanan is recited when the Tiqun is studied with a minyan. Today, this service is held in many communities, with the notable exception of Spanish and Portuguese Jews. The service is printed in a book called Tiqun Leyl Shavuot.[51] There exist similar books for the vigils before the seventh day of Pesach and Hosha'ana Rabbah.

In Jerusalem, at the conclusion of the night time study session, tens of thousands of people walk to the Western Wall to pray with sunrise. A week after Israel captured the Old City during the Six-Day War, more than 200,000 Jews streamed to the site on Shavuot, it having been made accessible to Jews for the first time since 1948.[48][52][53][54]

Modern secular observance

In secular agricultural communities in Israel, such as most kibbutzim and moshavim, Shavuot is celebrated as a harvest and first-fruit festival including a wider, symbolic meaning of joy over the accomplishments of the year. As such, not just agricultural produce and machinery is presented to the community, but also the babies born during the preceding twelve months.[55]

Confirmation ceremonies

In the 19th century several Orthodox synagogues in Britain and Australia held confirmation ceremonies for 12-year-old girls on Shavuot, a precursor to the modern Bat Mitzvah.[56] The early Reform movement made Shavuot into a religious school graduation day.[6] Today, Reform synagogues in North America typically hold confirmation ceremonies on Shavuot for students aged 16 to 18 who are completing their religious studies. The graduating class stands in front of an open ark, recalling the standing of the Israelites at Mount Sinai for the giving of the Torah.[57]

Dates in dispute

Since the Torah does not specify the actual day on which Shavuot falls, differing interpretations of this date have arisen in both traditional and non-traditional Jewish circles. These discussions center around two ways of looking at Shavuot: the day it actually occurs (i.e., the day the Torah was given on Mount Sinai), and the day it occurs in relation to the Counting of the Omer (being the 50th day from the first day of the Counting).[58]

Giving of the Torah

While most of the Talmudic Sages concur that the Torah was given on the sixth of Sivan in the Hebrew calendar, Rabbi Jose holds that it was given on the seventh of that month. According to the classical timeline, the Israelites arrived at the wilderness of Sinai on the new moon (Ex. 19:1) and the Ten Commandments were given on the following Shabbat (i.e., Saturday). The question of whether the new moon fell on Sunday or Monday is undecided (Talmud, tractate Shabbat 86b). In practice, Shavuot is observed on the sixth day of Sivan in Israel[59] and a second day is added in the Jewish diaspora (in keeping with a separate rabbinical ruling that applies to all biblical holidays, called Yom tov sheni shel galuyot, Second-Day Yom Tov in the diaspora).[60]

Counting of the Omer

The Torah states that the Omer offering (i.e., the first day of counting the Omer) is the first day of the barley harvest (Deut. 16:9). It should begin "on the morrow after the Shabbat", and continue to be counted for seven Sabbaths. (Lev. 23:11).

The Talmudic Sages determined that "Shabbat" here means a day of rest and refers to the first day of Passover. Thus, the counting of the Omer begins on the second day of Passover and continues for the next 49 days, or seven complete weeks, ending on the day before Shavuot. According to this calculation, Shavuot will fall on the day of the week after that of the first day of Passover (e.g., if Passover starts on a Thursday, Shavuot will begin on a Friday).

The Book of Jubilees and the Essenes

This literal interpretation of "Shabbat" as the weekly Shabbat was shared by the author of the Book of Jubilees, who was motivated by the priestly sabbatical solar calendar to have festivals and Sabbaths fall on the same day of the week every year. On this calendar (best known from the Book of Luminaries in the Book of Enoch), Shavuot fell on the 15th of Sivan, a Sunday. The date was reckoned fifty days from the first Shabbat after Passover (i.e. from the 25th of Nisan). Thus, Jub. 1:1 claims that Moses ascended Mount Sinai to receive the Torah "on the sixteenth day of the third month in the first year of the Exodus of the children of Israel from Egypt".

In Jub. 6:15–22 and 44:1–5, the holiday is traced to the appearance of the first rainbow on the 15th of Sivan, the day on which God made his covenant with Noah.

The Qumran community, commonly associated with the Essenes, held in its library several texts mentioning Shavuot, most notably a Hebrew original of the Book of Jubilees, which sought to fix the celebration of this Feast of Weeks on 15 of Sivan, following their interpretation of Exodus 19:1.[61] (See also above, at "Agricultural (wheat harvest)".)

Notes and references

- The Christian observance of Pentecost is a different holiday, but was based on a New Testament event that happened around the gathering of Jesus's followers on this Jewish holiday (Acts of the Apostles 2:1 and following).

- "Dates for Shavuot". Hebcal.com by Danny Sadinoff and Michael J. Radwin (CC-BY-3.0). Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- History Crash Course #36: Timeline: From Abraham to Destruction of the Temple, by Rabbi Ken Spiro, Aish.com. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- "What Is Shavuot (Shavuos)? – And How Is Shavuot Celebrated?". www.chabad.org.

- "Is Shavuot the Jewish Pentecost?". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- Neusner, Jacob (1991). An Introduction to Judaism: A Textbook and Reader. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-664-25348-6.

The Feast of Weeks, Shavuot, or Pentecost, comes seven weeks after Passover. In the ancient Palestinian agricultural calendar, Shavuot marked the end of the grain harvest and was called the 'Feast of Harvest'

- Goldberg, J.J. (May 12, 2010). "Shavuot: The Zeppo Marx of Jewish Holidays". The Forward. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Berel Wein (May 21, 2010). "Shavuot Thoughts". The Jerusalem Post.

Here in Israel all Israelis are aware of Shavuot, even those who only honor it in its breach ... In the diaspora, Shavuot is simply ignored by many Jews ...

- Jonathan Rosenblum (May 31, 2006). "Celebrating Shavuos Alone". Mishpacha. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

Yet most Jews have barely heard of Shavuos, the celebration of Matan Torah. In Eretz Yisrael, the contrast between Shavuos and the other yomim tovim could not be more stark. Shavuos is only about the acceptance of Torah. For those Israeli Jews for whom Torah has long since ceased to be relevant, the holiday offers nothing.

- See, for example, "BBC – Religions – Judaism:Shavuot". BBC. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Z'man matan toratenu ("the time of the giving of our Torah [Law]") is a frequent liturgical cognomen for Shavuot. See, for example, "The Standard Prayer Book:Kiddush for Festivals". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Press release based on work by Dr. Eshbal Ratson and Prof. Jonathan Ben-Dov, Department of Bible Studies (January 2018). "University of Haifa Researchers Decipher One of the Last Two Remaining Unpublished Qumran Scrolls". University of Haifa, Communications and Media Relations. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Sweeney, Marvin. "The Three Shavuot Festivals of Qumran: Wheat, Wine, and Oil". The Torah. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- Wilson, Marvin (1989). Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith. p. 43.

- Goodman, Robert (1997). Teaching Jewish Holidays: History, Values, and Activities. p. 215.

- "Shavuot 101".

- Pesachim 68b.

- Bogomilsky, Rabbi Moshe (2009). "Dvar Torah Questions and Answers on Shavuot". Sichos in English. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Wein, Rabbi Berel (2005). "Shavuos". torah.org. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- "Stop! It's Shavuot! by Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein". Ohr Somayach.

- The Temple Institute. "The Festival of Shavout: Bringing the Firstfruits to the Temple". The Temple Institute. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- "Customs of Shavuot". June 30, 2006.

- "The Baal Shem Tov – A Brief Biography". Chabad. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ""Akdamut" and "Ketubah"". June 30, 2006.

- Yonah Frankel, Shavuot Machzor, page 11 of the introduction.

- "YUTorah Online – Yatziv Pitgam, One of Our Last Aramaic Piyyutim (Dr. Lawrence Schiffman)".

- Wein, Rabbi Berel (May 10, 2005). "Cheese & Flowers". Aish.com. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Shavuot – Hag ha'Bikkurim or Festival of the First Fruits". In Mama's Kitchen. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Marks, Gil (2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. John Wiley & Sons. p. 524. ISBN 978-0-470-39130-3.

- Marks, Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, p. 87.

- Kaplan, Sybil. "Shavuot Foods Span Myriad Cultures". Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Kagan, Aaron (May 29, 2008). "Beyond Blintzes: A Culinary Tour of Shavuot". The Forward. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Shavuot Tidbits: An Overview of the Holiday". Torah Tidbits. ou.org. 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Simmons, Rabbi Shraga (May 27, 2006). "Why Dairy on Shavuot?". Aish.com. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Erdstein, Rabbi Baruch E.; Kumer, Nechama Dina (2011). "Why do we eat dairy foods on Shavuot?". AskMoses.com. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- The other four are the Book of Lamentations, read on Tisha B'Av; the Book of Ecclesiastes, read on Sukkot; the Book of Esther (Megillat Esther) read on Purim; and the Song of Songs, the reading for Passover. See Five Megillot for further details.

- Rosenberg, Yael. "Reading Ruth: Rhyme and Reason". Mazor Guide. Mazornet, Inc. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Ross, Lesli Koppelman. "Shavuot Decorations". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Goodman, Philip. "The Shavuot Marriage Contract". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Ross, Lesli Koppelman. "Shavuot Decorations". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Why Dairy on Shavuot? [ Reason #6 ]". May 28, 2006.

- Shir Hashirim Rabbah 1:57.

- Ullman, Rabbi Yirmiyahu (May 22, 2004). "Sleepless Shavuot in Shicago". Ohr Somayach. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Altshuler, Dr. Mor (December 22, 2008). "Tikkun Leil Shavuot of R. Joseph Karo and the Epistle of Solomon ha-Levi Elkabetz". jewish-studies.info. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- Altshuler, Mor (May 22, 2007). "Let each help his neighbor". Haaretz. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- "Joseph Karo". Jewish Virtual Library. 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- Sokolow, Moshe (May 24, 2012). "Sleepless on Shavuot". Jewish Ideas Daily. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- Horowitz, Elliot (1989). "Coffee, Coffeehouses, and the Nocturnal Rituals of Early Modern Jewry". AJS Review. 14 (1): 17–46. doi:10.1017/S0364009400002427. JSTOR 1486283.

- Fendel, Hillel (May 28, 2009). "Who Replaced My Cheese with Torah Study?". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- "Learning on Shavuot Night – Tikun Leil Shavuot – an Insomniac's Preparation for the Torah".

- "Tikkun Leil Shavuot".

- Ross, Lesli Koppelman. "Tikkun Leil Shavuot". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Wein, Rabbi Berel (May 16, 2002). "Shavuot: Sleepless Nights". Torah Women.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- "Shavuot". NSW Board of Jewish Education. 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Simmons, Rabbi Shraga (May 12, 2001). "ABC's of Shavuot". Aish.com. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- "What Do Jewish People Celebrate on Shavuot?". Learn Religions. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- Raymond Apple. "Origins of Bat-Mitzvah". OzTorah. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Katz, Lisa (2011). "What is Judaism's confirmation ceremony?". About.com. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Shavuot". Jewish FAQ. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- Goldin, Shmuel (2010). Unlocking the Torah Text: Vayikra. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 207. ISBN 9789652294500.

- Kohn, Daniel. "Why Some Holidays Last Longer Outside Israel". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- Joseph Fitzmyer Responses to 101 questions on the Dead Sea scrolls 1992 p. 87 – "Particularly important for the Qumran community was the celebration of this Feast of Weeks on III/15, because according to Ex. 19:1 Israel arrived in its exodus-wandering at Mt. Sinai in the third month after leaving Egypt. Later the renewal of the Covenant came to be celebrated on the Feast of Weeks. Qumran community was deeply researched by Flavius Josephus."

General sources

- Brofsky, David (2013). Hilkhot Moadim: Understanding the Laws of the Festivals. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers. ISBN 9781592643523.

- Kitov, Eliyahu (1978). The Book of Our Heritage: The Jewish Year and Its Days of Significance. Vol. 3: Iyar-Elul. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87306-151-3.

- Scherman, Nosson, ed. (1993). The Chumash: The Torah: Haftaros and Five Megillos with a Commentary Anthologized from the Rabbinic Writings. ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications. ISBN 978-0-89906-014-9.

External links

- Shavuot at Chabad.org

- Jewish Holidays: Shavuot at the Orthodox Union

- Jewish Confirmation at My Jewish Learning