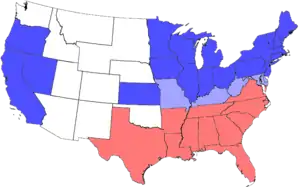

Slave states and free states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states to be politically imperative that the number of free states not exceed the number of slave states, so new states were admitted in slave–free pairs. There were, nonetheless, some slaves in most free states up to the 1840 census, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 specifically stated that a slave did not become free by entering a free state.

Although Native Americans had small-scale slavery, slavery in what would become the United States was established as part of European colonization. By the 18th century, slavery was legal throughout the Thirteen Colonies, after which rebel colonies started to abolish the practice. Pennsylvania abolished slavery in 1780, and about half the states abolished slavery by the end of the Revolutionary War or in the first decades of the new country, although this did not usually mean that existing slaves became free. Although not one of the Thirteen Colonies, Vermont declared its independence from Britain in 1777 and at the same time limited slavery, before being admitted as a state in 1791.

Slavery was a divisive issue in the United States. It was a major issue during the writing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 and was the primary cause of the American Civil War in 1861. Just before the Civil War, there were 19 free states and 15 slave states. During the war, slavery was abolished in some of these jurisdictions, and the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in December 1865, finally abolished slavery throughout the United States.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Early history

Slavery was established as a legal institution in each of the Thirteen Colonies, starting from 1619 onwards with the arrival of "twenty and odd" enslaved Africans in Virginia. Although indigenous peoples were also sold into slavery, the vast majority of the enslaved population consisted of Africans brought to the Americas via the Atlantic slave trade. Due to a lower prevalence of tropical diseases and better treatment, the enslaved population in the colonies had a higher life expectancy than in the West Indies and South America, leading to a rapid increase in population in the decades prior to the American Revolution.[1][2] Organized political and social movements to end slavery began in the mid-18th century.[3] The sentiments of the American Revolution and the promise of equality evoked by the Declaration of Independence stood in contrast to the status of most Blacks, either free or enslaved, in the colonies. Despite this, thousands of Black Americans fought for the Patriot cause for a combination of reasons. Thousands also joined the British, encouraged by offers of freedom such as the Philipsburg Proclamation.[3]

In the 1770s, enslaved Black people throughout New England began sending petitions to northern legislatures demanding freedom. Five of the Northern self-declared states adopted policies to at least gradually abolish slavery: Pennsylvania in 1780, New Hampshire and Massachusetts in 1783, and Connecticut and Rhode Island in 1784. The Republic of Vermont had limited slavery in 1777, while it was still independent before it joined the United States as the 14th state in 1791. These state jurisdictions thus enacted the first abolition laws in the Atlantic World.[4] By 1804 (including New York (1799) and New Jersey (1804)), all of the Northern states had abolished slavery or set measures in place to gradually abolish it,[3][5] although there were still hundreds of ex-slaves working without pay as indentured servants in Northern states as late as the 1840 census (see Slavery in the United States#Abolitionism in the North).

In the South, Kentucky was created a slave state from Virginia (1792), and Tennessee was created a slave state from North Carolina (1796). By 1804, before the creation of new states from the federal western territories, the number of slave and free states was 8 each. By the time of Missouri Compromise of 1820, the dividing line between the slave and free states was called the Mason-Dixon line (between Maryland and Pennsylvania), with its westward extension being the Ohio River.

The 1787 Constitutional Convention debated slavery, and for a time slavery was a major impediment to passage of the new constitution. As a compromise, slavery was acknowledged but never mentioned explicitly in the Constitution. The Fugitive Slave Clause, Article IV, section 2, clause 3, for example, refers to a "Person held to Service or Labour." In addition, Article 1, section 9, clause 1 of the Constitution prohibited Congress from abolishing the importation of slaves, but in a compromise, the prohibition could be lifted by Congress in twenty years, and slaves were referred to as "Persons." The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves passed easily in 1807, effective in 1808. However, the ban on importation spurred an expansion in the domestic slave trade, which remained legal until slavery was banned entirely in 1865 by the 13th Amendment.

In the late 1850s an unsuccessful campaign was launched by several southern states to resume the international slave trade, to restock their slave populations, but this met with strong opposition.[6] However, there was large natural increase in the slave population throughout the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, while some illegal smuggling of African slaves continued via Spanish Cuba.

One of the other compromises of the Constitution was the creation of the three-fifths clause by which slave states acquired increased representation in the House of Representatives and Electoral College equivalent to 60 percent of their disenfranchised slave populations. Slave states had wanted 100 percent of their slaves to be counted, whereas Northern states argued that none should be.

New territories

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, passed just before the U.S. Constitution was ratified, had prohibited slavery in the federal Northwest Territory. The southern boundary of the territory was the Ohio River, which was regarded as a westward extension of the Mason-Dixon line. The territory was generally settled by New Englanders and American Revolutionary War veterans granted land there. The 6 states created from the territory were all free states: Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837), Wisconsin (1848), and Minnesota (1858).[7]

By 1815, the momentum for antislavery reform, state by state, appeared to run out of steam, with half of the states having already abolished slavery (Northeast), prohibited from the start (Midwest) or committed to eliminating slavery, and half committed to continuing the institution indefinitely (South).

The potential for political conflict over slavery at a federal level made politicians concerned about the balance of power in the Senate, where each State was represented by two senators. With an equal number of slave states and free states, the Senate was equally divided on issues important to the South. As the population of the free states began to outstrip the population of the slave states, leading to control of the House of Representatives by free states, the Senate became the preoccupation of slave-state politicians interested in maintaining a congressional veto over federal policy in regard to slavery and other issues important to the South. As a result of this preoccupation, slave states and free states were often admitted into the Union in opposite pairs to maintain the existing Senate balance between slave and free states.

Missouri Compromise

Controversy over whether Missouri should be admitted as a slave state resulted in the Missouri Compromise of 1821, which specified that territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36° 30', which described most of Missouri's southern boundary, would be organized as free states and territory south of that line would be reserved for organization as slave states. As part of the compromise, the admission of Maine (August 19, 1821) as a free state was enabled by Missouri's compromise to join the union as a slave state (August 19, 1821).[8]

Texas and the Mexican Cession

The admission of Texas (1845) and the acquisition of the vast new Mexican Cession territories (1848), after the Mexican–American War, created further North-South conflict. Although the settled portion of Texas was an area rich in cotton plantations and dependent on slave labor, the territory acquired in the Mountain West did not seem hospitable to cotton or slavery.[9]

As part of the Compromise of 1850, California was admitted as a free state without a slave state pair; California's admission also meant there would be no slave state on the Pacific Ocean. To avoid creating a free state majority in the Senate, California agreed to send one pro-slavery and one anti-slavery senator to Congress.[10]

Last battles

The difficulty of identifying territory that could be organized into additional slave states stalled the process of opening the western territories to settlement, while slave-state politicians sought a solution, with efforts being made to acquire Cuba (see: Lopez Expedition and Ostend Manifesto, 1852) and to annex Nicaragua (see: Walker affair, 1856–57), both to be slave states. Parts of Northern Mexico were also coveted, with Senator Albert Brown declaring "I want Tamaulipas, Potosi, and one or two other Mexican States; and I want them all for the same reason – for the plantation and spreading of slavery".[11]

Kansas

In 1854, the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was superseded by the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed white male settlers in the new territories to determine, by vote (popular sovereignty), whether they would allow slavery within each territory. The result was that pro- and anti-slavery elements flooded into Kansas with the goal of voting slavery up or down, leading to bloody fighting.[12] An effort was initiated to organize Kansas for admission as a slave state, paired with Minnesota, but the admission of Kansas as a slave state was blocked because its proposed pro-slavery constitution (the Lecompton Constitution) had not been approved in an honest election. Anti-slavery proponents during the "Bleeding Kansas" period of the later 1850s were called Free-Staters and Free-Soilers, and fought against pro-slavery Border Ruffians from Missouri. The animosity escalated throughout the 1850s, culminating in numerous skirmishes and devastation on both sides of the question. Nevertheless, the North prevented Kansas Territory from becoming a slave state, and when Southern members of Congress departed en masse in early 1861, Kansas was immediately admitted to the Union as a free state.

When the admission of Minnesota proceeded unimpeded in 1858, the balance in the Senate ended; this was compounded by the subsequent admission of Oregon as a free state in 1859.

Slave and free state pairs

Before 1812, the concern about balancing slave-states and free states was not deeply considered. The following table shows the slave and free states as of 1812. The year column is the year the state ratified the US Constitution or was admitted to the Union:[13]

| Slave states | Year | Free states | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delaware | 1787 | New Jersey (Slave until 1804) | 1787 |

| Georgia | 1788 | Pennsylvania | 1787 |

| Maryland | 1788 | Connecticut | 1788 |

| South Carolina | 1788 | Massachusetts | 1788 |

| Virginia | 1788 | New Hampshire | 1788 |

| North Carolina | 1789 | New York (Slave until 1799) | 1788 |

| Kentucky | 1792 | Rhode Island | 1790 |

| Tennessee | 1796 | Vermont | 1791 |

| Louisiana | 1812 | Ohio | 1803 |

From 1812 through 1850, maintaining the balance of free and slave state votes in the Senate was considered of paramount importance if the Union were to be preserved, and states were typically admitted in pairs:

| Slave states | Year | Free states | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | 1817 | Indiana | 1816 |

| Alabama | 1819 | Illinois | 1818 |

| Missouri | 1821 | Maine | 1820 |

| Arkansas | 1836 | Michigan | 1837 |

| Florida | 1845 | Iowa | 1846 |

| Texas | 1845 | Wisconsin | 1848 |

The balance was maintained until 1850:

| Slave states | Year | Free states | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | 1850 | ||

| Minnesota | 1858 | ||

| Oregon | 1859 | ||

| Kansas | 1861 |

Civil War

The American Civil War (1861–1865) disrupted and eventually ended slavery. Eleven slave states joined the Confederacy, while the border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri remained in the Union, despite the presence of slavery within their borders. In 1863 western Virginia, much of which had remained loyal to the Union, was admitted as the new state of West Virginia with a commitment to gradual emancipation. The following year Nevada, a free state in the West, was also admitted.

| Slave state | Year | Free state | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Virginia (gradual abolition plan) | 1863 | Nevada | 1864 |

Special cases

West Virginia

During the Civil War, a Unionist government in Wheeling, Virginia, presented a statehood bill to Congress to create a new state from 48 counties in western Virginia. The new state would eventually incorporate 50 counties. The issue of slavery in the new state delayed approval of the bill. In the Senate Charles Sumner objected to the admission of a new slave state, while Benjamin Wade defended statehood as long as a gradual emancipation clause would be included in the new state constitution.[14] Two senators represented the Unionist Virginia government, John S. Carlile and Waitman T. Willey. Senator Carlile objected that Congress had no right to impose emancipation on West Virginia, while Willey proposed a compromise amendment to the state constitution for gradual abolition. Sumner attempted to add his own amendment to the bill, which was defeated, and the statehood bill passed both houses of Congress with the addition of what became known as the Willey Amendment. President Lincoln signed the bill on December 31, 1862. Voters in western Virginia approved the Willey Amendment on March 26, 1863.[15]

President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which exempted from emancipation the border states (four slave states loyal to the Union) as well as some territories occupied by Union forces within Confederate states. Two additional counties were added to West Virginia in late 1863, Berkeley and Jefferson. The slaves in Berkeley were also under exemption but not those in Jefferson County. As of the census of 1860, the 49 exempted counties held some 6000 slaves over 21 years of age who would not have been emancipated, about 40% of the total slave population.[16] The terms of the Willey Amendment only freed children, at birth or as they came of age, and prohibited the importation of slaves.[17]

West Virginia became the 35th state on June 20, 1863, and the last slave state admitted to the Union.[18][19][20] Eighteen months later, the West Virginia legislature completely abolished slavery,[21] and also ratified the 13th Amendment on February 3, 1865.

Washington D.C.

In the District of Columbia, formed with land from two slave states, Maryland and Virginia, the trade was abolished by the Compromise of 1850. So as to avoid losing the profitable slave trading businesses in Alexandria (one was Franklin and Armfield), Alexandria County, D.C., requested that it be returned to Virginia, where the slave trade was legal; this took place in 1847. Slavery in the District of Columbia remained legal until 1862, when the walkout of all the Southern legislators permitted those remaining to pass the ban, which abolitionists had been seeking for decades.

Utah Territory

Although it did not become a state until 1896, as an organized territory, Utah legalized slavery under the 1852 territorial Act in Relation to Service and similar Act for the Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners.

Brigham Young and his group of Mormon pioneers had arrived in Utah in 1847, during the Mexican–American War, when Utah Territory was Mexican territory. They ignored the Mexican ban on slavery. They viewed slavery as consistent with the Mormon view on Black people.[22]

On June 19, 1862, fulfilling a part of his 1860 campaign platform, President Lincoln signed the law ending slavery in Utah Territory and all other territories.[23]

End of slavery

At the start of the Civil War, there were 34 states in the United States, 15 of which were slave states. Eleven of these slave states, after conventions devoted to the topic, issued declarations of secession from the United States, created the Confederate States of America, and were represented in the Confederate Congress.[24][25] The slave states that stayed in the Union — Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and Kentucky (called border states) — retained their representatives in the U.S. Congress. By the time the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, Tennessee was already under Union control.[26] Accordingly, the Proclamation applied only in the 10 remaining Confederate states. During the war, abolition of slavery was required by President Abraham Lincoln for readmission of Confederate states.[27]

The U.S. Congress, after the departure of the powerful Southern contingent in 1861, was generally abolitionist: In a plan endorsed by Abraham Lincoln, slavery in the District of Columbia, which the Southern contingent had protected, was abolished in 1862.[28]

In Southern states, the legal elimination of slavery typically followed Union control. The Emancipation Proclamation declared all enslaved people in areas then under Confederate control free, but, in practice, freedom required either slaves reaching Union lines or Union forces reaching their area. As Union forces advanced from January 1, 1863 to June 19, 1865, slaves were freed.

West Virginia did not abolish slavery in its first proposed constitution of 1861, though it did ban the importation of slaves.[29] In 1863, voters approved the Willey Amendment, which provided for gradual abolition of slavery, with the last enslaved people scheduled to be freed in 1884.[30] On February 3, 1865, the state legislature approved immediate abolition.[31]

The Restored Government of Virginia — the Unionist government that governed the limited territory then under Union control that had not left to form West Virginia — voted to end slavery at a constitutional convention on March 10, 1864.[32] Arkansas, part of which came under Union control by 1864, adopted an anti-slavery constitution on March 16, 1864.[33] Louisiana — much of which had been under Union control since 1862 — abolished slavery through a new state constitution approved by voters September 5, 1864.[34] The border states of Maryland (November 1, 1864)[35] and Missouri (January 11, 1865)[36] abolished slavery before the war's end. The Union-occupied state of Tennessee abolished slavery by popular vote on a constitutional amendment that took effect February 22, 1865.[37]

However, slavery legally persisted in Delaware,[38] Kentucky,[39] and (to a very limited extent) New Jersey,[40][41] until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery throughout the United States on December 18, 1865, ending the distinction between slave and free states.[42]

See also

- Border states (American Civil War)

- Golden Circle (proposed country)

- Quilombo

- Slavery in the colonial United States

- Slavery in the United States

- Wilmot Proviso

References

- Painter, Nell Irvin. (2006). Creating Black Americans: African-American history and its meanings, 1619 to the present. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-19-513755-8. OCLC 57722517.

- Betty Wood, Slavery in Colonial America, 1619–1776 (2013) excerpt and text search

- Painter, Nell Irvin (2006). Creating Black Americans: African-American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-0195137569.

- Foner, Eric (2010). The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-513755-2.

- Wilson, Black Codes (1965), p. 15. "By 1775, inspired by those 'self-evident' truths which were to be expressed by the Declaration of Independence, a considerable number of colonists felt that the time had come to end slavery and give the free Negroes some fruits of liberty. This sentiment, added to economic considerations, led to the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery in six Northern states, while there was a swelling flood of private manumissions in the South. Little actual gain was made by the free Negro even in this period, and by the turn of the century the downward trend had begun again. Thereafter the only important change in that trend before the Civil War was that after 1831 the decline in the status of the free Negro became more precipitate."

- William W. Freehling. The Road to Disunion, Volume II : Secessionists Triumphant Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854–1861: Secessionists Triumphant Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854–1861. Oxford University Press, 2007. p.168-85

- "LIBERTY! . Northwest Ordinance". PBS. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- Ken S. Mueller, "Wolf by the Ears: The Missouri Crisis, 1819–1821 by John R. Van Atta." Journal of the Early Republic 37.1 (2017): 173–175 online.

- Michael A. Morrison, "Westward the Curse of Empire: Texas Annexation and the American Whig Party.” Journal of the Early Republic 10#2 (1990): 221–249 online

- Michael E. Woods, "The Compromise of 1850 and the Search for a Usable Past." Journal of the Civil War Era 9.3 (2019): 438–456.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press, 2003. p.105

- Nicole Etcheson. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (2006). ch 1.

- Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780—1860 (LSU Press, 2000).

- James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865, W.W. Norton, 2012, pgs. 296-97

- "West Virginians Approve the Willey Amendment". wvculture.org. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "University of Virginia Library". virginia.edu. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "Willey Amendment". wvculture.org. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Alton Hornsby, Jr.,Black America, A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia, Greenwood, 2011, vol. 2, pg. 922

- "West Virginia Statehood". wvculture.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "African-Americans in West Virginia". wvculture.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- "On This Day in West Virginia History – February 3". wvculture.org. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- John Williams Gunnison (1852). The Mormons: Or, Latter-day Saints, in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake: a History of Their Rise and Progress, Peculiar Doctrines, Present Condition, and Prospects, Derived from Personal Observation, During a Residence Among Them. Lippincott, Grambo & Company. p. 143.

Involuntary labor by negroes is recognized by custom; those holding slaves keep them as part of their family, as they would their wives, without any law on the subject. Negro caste springs naturally from their doctrine of blacks being ineligible to the priesthood

. - Arrington, Benjamin (June 19, 2018). "The Significance of June 19th". We're History. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- Martis, Kenneth C. (1994). The Historical Atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865. Simon & Schuster. p. 7. ISBN 0-02-920170-5.

- Only Virginia, Tennessee and Texas held referendums to ratify their Fire-Eater declarations of secession, and Virginia's excluded Unionist county votes and included Confederate troops in Richmond voting as regiments viva voce.Dabney, Virginius. (1983). Virginia: The New Dominion, a History from 1607 to the Present. Doubleday. p. 296. ISBN 9780813910154.

- Eleven states had seceded, but Tennessee was under Union control.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2018). Reconstruction: A Concise History. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-086569-6. OCLC 999309004.

- American Memory "Abolition in the District of Columbia", Today in History, Library of Congress, viewed December 15, 2014. On April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed a congressional act abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for slave owners, five months before the victory at Antietam led to the Emancipation Proclamation.

- Lewis, Virgil Anson (1889). History of West Virginia: in two parts. pp. 379–380. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- West Virginia Legislature (March 15, 2021). "House Concurrent Resolution 49". Retrieved November 24, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The Abolition of Slavery in Virginia". Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- "Education from LVA: Convention Resolved to Abolish Slavery". edu.lva.virginia.gov. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016.

- "Freedmen and Southern Society Project: Chronology of Emancipation". www.freedmen.umd.edu. University of Maryland. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "Reconstruction: A State Divided". January 23, 2014.

- "Archives of Maryland Historical List: Constitutional Convention, 1864". November 1, 1864. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "Missouri abolishes slavery". January 11, 1865. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- United States. Congress. Joint Committee on Reconstruction; United States. Congress (1866). Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, at the First Session, Thirty-ninth Congress: Resolutions, committees, etc. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-0-598-67518-7. OCLC 17596217.

- "Slavery in Delaware". Slavenorth.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; Klotter, James C. (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. p. 180. ISBN 0813126215. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- "Slavery in the Middle States (NJ, NY, PA)". Encyclopedia.com. July 16, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Smith, Geneva. "Legislating Slavery in New Jersey". Princeton & Slavery. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Kocher, Greg (February 23, 2013). "Kentucky supported Lincoln's efforts to abolish slavery — 111 years late | Lexington Herald-Leader". Kentucky.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

Further reading

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Ward M. Mcafee; The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government's Relations to Slavery (2002)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Slavery in the United States: A social, political, and historical encyclopedia (2 vol Abc-clio, 2007).