Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (/ˈbɛkɪt/), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London[1] and later Thomas à Becket[note 1] (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then notably as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion. He engaged in conflict with Henry II, King of England, over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, he was canonised by Pope Alexander III.

Saint Thomas Becket | |

|---|---|

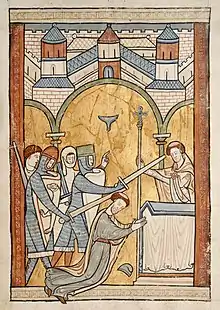

One of the earliest known depictions of Becket's assassination, c. 1175–1225 | |

| Church | Latin Church |

| Archdiocese | Canterbury |

| See | Canterbury |

| Appointed | 24 May 1162 |

| Term ended | 29 December 1170 |

| Predecessor | Theobald of Bec |

| Successor | Roger de Bailleul (Archbishop-elect) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 2 June 1162 |

| Consecration | 3 June 1162 by Henry of Blois |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 December c. 1119 Cheapside, London, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 29 December 1170 (age 50 or 51) Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, Kingdom of England |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral |

| Denomination | Catholicism |

| Parents |

|

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Coat of arms |  |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 29 December |

| Venerated in | |

| Beatified | by Pope Alexander III |

| Canonized | 21 February 1173 by Pope Alexander III |

| Attributes | Sword, martyrdom, episcopal vestments |

| Patronage | Exeter College, Oxford; Portsmouth; Arbroath Abbey; secular clergy; City of London |

| Shrines | Canterbury Cathedral |

| Cult suppressed | 1538 (by Henry VIII) |

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office 1155–1162 | |

| Monarch | Henry II |

| Preceded by | Robert of Ghent |

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Ridel |

Sources

The main sources for the life of Becket are a number of biographies written by contemporaries. A few of these documents are by unknown writers, although traditional historiography has given them names. The known biographers are John of Salisbury, Edward Grim, Benedict of Peterborough, William of Canterbury, William fitzStephen, Guernes of Pont-Sainte-Maxence, Robert of Cricklade, Alan of Tewkesbury, Benet of St Albans, and Herbert of Bosham. The other biographers, who remain anonymous, are generally given the pseudonyms of Anonymous I, Anonymous II (or Anonymous of Lambeth), and Anonymous III (or Lansdowne Anonymous). Besides these accounts, there are also two other accounts that are likely contemporary that appear in the Quadrilogus II and the Thómas saga Erkibyskups. Besides these biographies, there is also the mention of the events of Becket's life in the chroniclers of the time. These include Robert of Torigni's work, Roger of Howden's Gesta Regis Henrici Secundi and Chronica, Ralph Diceto's works, William of Newburgh's Historia Rerum, and Gervase of Canterbury's works.[3]

Early life

Becket was born c. 1119,[4] or in 1120 according to later tradition,[1] at Cheapside, London, on 21 December, the feast day of St Thomas the Apostle. He was the son of Gilbert and Matilda Beket[note 2] Gilbert's father was from Thierville in the lordship of Brionne in Normandy, and was either a small landowner or a petty knight.[1] Matilda was also of Norman descent[2] – her family may have originated near Caen. Gilbert was perhaps related to Theobald of Bec, whose family was also from Thierville. Gilbert began his life as a merchant, perhaps in textiles, but by the 1120s he was living in London and was a property owner, living on the rental income from his properties. He also served as the sheriff of the city at some point.[1] They were buried in Old St Paul's Cathedral.

One of Becket's father's wealthy friends, Richer de L'Aigle, often invited Thomas to his estates in Sussex, where Becket encountered hunting and hawking. According to Grim, Becket learned much from Richer, who was later a signatory of the Constitutions of Clarendon against him.[1]

At the age of 10, Becket was sent as a student to Merton Priory south-west of the city in Surrey. He later attended a grammar school in London, perhaps the one at St Paul's Cathedral. He did not study any subjects beyond the trivium and quadrivium at these schools. Around the age of 20, he spent about a year in Paris, but he did not study canon or civil law at the time and his Latin skill always remained somewhat rudimentary. Some time after Becket began his schooling, Gilbert Becket suffered financial reverses and the younger Becket was forced to earn a living as a clerk. Gilbert first secured a place for his son in the business of a relative – Osbert Huitdeniers. Later Becket acquired a position in the household of Theobald of Bec, by then Archbishop of Canterbury.[1]

Theobald entrusted him with several important missions to Rome and also sent him to Bologna and Auxerre to study canon law. In 1154, Theobald named Becket Archdeacon of Canterbury, and other ecclesiastical offices included a number of benefices, prebends at Lincoln Cathedral and St Paul's Cathedral, and the office of Provost of Beverley. His efficiency in those posts led Theobald to recommend him to King Henry II for the vacant post of Lord Chancellor,[1] to which Becket was appointed in January 1155.[7]

As Chancellor, Becket enforced the king's traditional sources of revenue that were exacted from all landowners, including churches and bishoprics.[1] King Henry sent his son Henry to live in Becket's household, it being the custom then for noble children to be fostered out to other noble houses.

Primacy

Becket was nominated as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, several months after the death of Theobald. His election was confirmed on 23 May 1162 by a royal council of bishops and noblemen.[1] Henry may have hoped that Becket would continue to put royal government first, rather than the church, but the famed transformation of Becket into an ascetic occurred at this time.[8]

- Becket enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury from a Nottingham Alabaster in the Victoria & Albert Museum

Becket was ordained a priest on 2 June 1162 at Canterbury, and on 3 June 1162 was consecrated as archbishop by Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester and the other suffragan bishops of Canterbury.[1]

A rift grew between Henry and Becket as the new archbishop resigned his chancellorship and sought to recover and extend the rights of the archbishopric. This led to a series of conflicts with the King, including one over the jurisdiction of secular courts over English clergymen, which accelerated antipathy between Becket and the king. Attempts by Henry to influence other bishops against Becket began in Westminster in October 1163, where the King sought approval of the traditional rights of royal government in regard to the church.[1] This led to the Constitutions of Clarendon, where Becket was officially asked to agree to the King's rights or face political repercussions.

Constitutions of Clarendon

King Henry II presided over assemblies of most of the higher English clergy at Clarendon Palace on 30 January 1164. In 16 constitutions he sought less clerical independence and weaker connections with Rome. He used his skills to induce their consent and apparently succeeded with all but Becket. Finally, even Becket expressed willingness to agree to the substance of the Constitutions of Clarendon, but he still refused formally to sign the documents. Henry summoned Becket to appear before a great council at Northampton Castle on 8 October 1164, to answer allegations of contempt of royal authority and malfeasance in the Chancellor's office. Convicted on the charges, Becket stormed out of the trial and fled to the Continent.[1]

Henry pursued the fugitive archbishop with a series of edicts, targeting Becket and all Becket's friends and supporters, but King Louis VII of France offered Becket protection. He spent nearly two years in the Cistercian abbey of Pontigny, until Henry's threats against the order obliged him to return to Sens. Becket fought back by threatening excommunication and an interdict against the king and bishops and the kingdom, but Pope Alexander III, though sympathising with him in theory, favoured a more diplomatic approach. Papal legates were sent in 1167 with authority to act as arbitrators.[1]

In 1170, Alexander sent delegates to impose a solution to the dispute. At that point, Henry offered a compromise that would allow Thomas to return to England from exile.[1]

Assassination

In June 1170, Roger de Pont L'Évêque, Archbishop of York, was at York with Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, and Josceline de Bohon, Bishop of Salisbury, to crown the heir apparent, Henry the Young King. This breached Canterbury's privilege of coronation and in November 1170 Becket excommunicated all three.[10]

On hearing reports of Becket's actions, Henry is said to have uttered words interpreted by his men as wishing Becket killed.[11] The exact wording is in doubt and several versions were reported.[12] The most commonly quoted, as invented in 1740 and handed down by oral tradition, is "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?",[13] but according to historian Simon Schama this is incorrect: he accepts the account of the contemporary biographer Edward Grim, writing in Latin, who gives, "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?"[14] Many other variants have found their way into popular culture.

Regardless of what Henry said, it was interpreted as a royal command. Four knights,[11] Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton,[1] set out to confront the Archbishop of Canterbury. On 29 December 1170, they arrived at Canterbury. According to accounts by the monk Gervase of Canterbury and eyewitness Edward Grim, the knights placed their weapons under a tree outside the cathedral and hid their armour under cloaks before entering to challenge Becket. The knights told Becket he was to go to Winchester to give an account of his actions, but Becket refused. Not until he refused their demands to submit to the king's will did they retrieve their weapons and rush back inside for the killing.[15] Becket, meanwhile, proceeded to the main hall for vespers. The other monks tried to bolt themselves in for safety, but Becket said to them, "It is not right to make a fortress out of the house of prayer!", ordering them to reopen the doors.

The four knights, wielding drawn swords, ran into the room crying, "Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King and country?" They found Becket in a spot near a door to the monastic cloister, the stairs into the crypt, and the stairs leading up into the quire of the cathedral, where the monks were chanting vespers.[1] On seeing them, Becket said, "I am no traitor and I am ready to die." One knight grabbed him and tried to pull him outside, but Becket grabbed onto a pillar and bowed his head to make peace with God.[16]

Several contemporary accounts of what happened next exist; of particular note is that of Grim, who was wounded in the attack. This is part of his account:

...the impious knight... suddenly set upon him and [shaved] off the summit of his crown which the sacred chrism consecrated to God... Then, with another blow received on the head, he remained firm. But with the third the stricken martyr bent his knees and elbows, offering himself as a living sacrifice, saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church I am ready to embrace death." But the third knight inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one; with this blow... his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church... The fifth – not a knight but a cleric who had entered with the knights... placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and (it is horrible to say) scattered the brains with the blood across the floor, exclaiming to the rest, "We can leave this place, knights, he will not get up again."[17]

Another account appears in Expugnatio Hibernica ("Conquest of Ireland", 1189) by Gerald of Wales.[18]

After Becket's death

After his death, the monks prepared Becket's body for burial.[1] According to some accounts, it was found that Becket had worn a hairshirt under his archbishop's garments — a sign of penance.[19] Soon after, the faithful throughout Europe began venerating Becket as a martyr, and on 21 February 1173 – little more than two years after his death – he was canonised by Pope Alexander III in St Peter's Church, Segni.[1] In 1173, Becket's sister Mary was appointed Abbess of Barking as reparation for the murder of her brother.[20] On 12 July 1174, amidst the Revolt of 1173–74, Henry humbled himself in public penance at Becket's tomb and at the church of St. Dunstan's, which became a most popular pilgrimage site.

Becket's assassins fled north to de Morville's Knaresborough Castle for about a year. De Morville also held property in Cumbria and this too may have provided a hiding place, as the men prepared for a longer stay in the separate kingdom of Scotland. They were not arrested and Henry did not confiscate their lands, but he did not help them when they sought his advice in August 1171. Pope Alexander excommunicated all four. Seeking forgiveness, the assassins travelled to Rome, where the Pope ordered them to serve as knights in the Holy Lands for a period of 14 years.[21]

This sentence also inspired the Knights of Saint Thomas, incorporated in 1191 at Acre, and which was to be modelled on the Teutonic Knights. This was the only military order native to England (with chapters in not only Acre, but London, Kilkenny, and Nicosia), just as the Gilbertine Order was the only monastic order native to England. Henry VIII dissolved both of these during the Reformation, rather than merging them with foreign orders or nationalising them as elements of the Protestant Church of England.

The monks were afraid Becket's body might be stolen, and so his remains were placed beneath the floor of the eastern crypt of the cathedral.[21] A stone cover over it had two holes where pilgrims could insert their heads and kiss the tomb,[1] as illustrated in the "Miracle Windows" of the Trinity Chapel. A guard chamber (now the Wax Chamber) had a clear view of the grave. In 1220, Becket's bones were moved to a new gold-plated, bejewelled shrine behind the high altar in the Trinity Chapel.[22] The shrine was supported by three pairs of pillars on a raised platform with three steps. This is shown in one of the miracle windows. Canterbury's religious history had always brought many pilgrims, and after Becket's death the numbers rapidly rose further.

Cult in the Middle Ages

In Scotland, King William the Lion ordered the building of Arbroath Abbey in 1178. On completion in 1197 the new foundation was dedicated to Becket, whom the king had known personally while at the English court as a young man.

On 7 July 1220, the 50th jubilee year of his death, Becket's remains were moved from his first tomb to a shrine in the recently built Trinity Chapel.[1] This translation was "one of the great symbolic events in the life of the medieval English Church", attended by King Henry III, the papal legate, the Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton and many dignitaries and magnates secular and ecclesiastical.

So a "major new feast day was instituted, commemorating the translation... celebrated each July almost everywhere in England and in many French churches."[24] It was suppressed in 1536 with the Reformation.[25]

The shrine was destroyed in 1538 during the Dissolution of the Monasteries on orders from King Henry VIII.[1][26] He also destroyed Becket's bones and ordered all mention of his name obliterated.[26][27]

As the scion of a mercantile dynasty of later centuries, Mercers, Becket was much regarded as a Londoner by citizens and adopted as London's co-patron saint with St Paul: both appear on the seals of the city and of the Lord Mayor. The Bridge House Estates seal has only a Becket image, while his martyrdom shown on the reverse.

The cult included the drinking of "water of Saint Thomas", a mix of water and the remains of the martyr's blood miraculously multiplied. The procedure was frowned upon by the more orthodox, due to the similarities with the eucharist of the blood of Jesus.[28]

Local legends regarding Becket arose after his canonisation. Though they tend towards typical hagiography, they also display Becket's well-known gruffness. "Becket's Well", in Otford, Kent, is said to have been created after Becket had been displeased by the taste of the local water. Two springs of clear water are said to have bubbled up after he struck the ground with his crozier. The absence of nightingales in Otford is also ascribed to Becket, who is said to have been so disturbed in his devotions by the song of a nightingale and commanded that none sing in the town ever again. In the town of Strood, Kent, Becket is said to have caused the inhabitants and their descendants to be born with tails. The men of Strood had sided with the king in his struggles against the archbishop, and to demonstrate their support had cut off the tail of Becket's horse as he passed through the town.

The saint's fame quickly spread through the Norman world. The first holy image of Becket is thought to be a mosaic icon still visible in Monreale Cathedral in Sicily, created shortly after his death. Becket's cousins obtained refuge at the Sicilian court during their exile, and King William II of Sicily wed a daughter of Henry II. Marsala Cathedral in western Sicily is dedicated to Becket. Over 45 medieval chasse reliquaries decorated in champlevé enamel showing similar scenes from Becket's life survive, including the Becket Casket, constructed to hold relics of him at Peterborough Abbey and now housed in London's Victoria and Albert Museum.

Legacy

- In 1170 King Alfonso VIII of Castille married Eleanor Plantagenet, second daughter of Henry II. She honoured Becket with a wall painting of his martyrdom that survives in the church of San Nicolás de Soria in Spain.[29] Becket's assassination made an impact in Spain: within five years of his death Salamanca had a church named after him, Iglesia de Santo Tomás Cantuariense. A monumental frescoes with the martyrdom of Thomas Becket were depicted in the romanesque church of Santa Maria at Terrassa.

- Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales features a company of pilgrims walking from Southwark to Becket's shrine in Canterbury Cathedral.

- The story of Becket's life became a popular theme for medieval Nottingham Alabaster carvers. One set of Becket panels is shown in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[30][31][32]

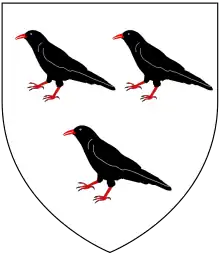

- The arms of the City of Canterbury, officially registered in 1619 but dating back to at least 1380, is based on the attributed arms of Thomas Becket: Argent, three Cornish choughs proper, with the addition of a chief gules charged with a lion passant guardant or from the Royal Arms of England.[33]

- In 1884, England's poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote Becket, a play about Thomas Becket and Henry II that Henry Irving produced after Tennyson's death and played in the title role.[34]

- Modern works based on the Becket story include T. S. Eliot's play Murder in the Cathedral (adapted as the opera Assassinio nella cattedrale by Ildebrando Pizzetti), Jean Anouilh's play Becket, where Becket is not a Norman but a Saxon. This became a movie with that title, and Paul Webb's play Four Nights in Knaresborough, which Webb adapted for the screen, selling the rights to Harvey and Bob Weinstein.[35] The power struggle between Church and King is a theme of Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth, where a late scene features the murder of Becket. Medieval mystery author Jeri Westerson recreated Chaucer's pilgrims and their time in Canterbury, with the murder and the theft of Becket's bones, in her fourth Crispin Guest novel, Troubled Bones.[36] An oratorio by David Reeves, Becket (The Kiss of Peace), was premièred in 2000 at Canterbury Cathedral, where the event had occurred, as a part of the Canterbury Festival, and a fundraiser for the Prince's Trust.[37][38]

- The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a non-profit, non-partisan legal and educational institute fostering free expression for religious traditions took its inspiration from Thomas Becket.[39]

- In a 2006 poll by BBC History magazine for "worst Briton" of the previous millennium, Becket came second behind Jack the Ripper.[40] The poll was dismissed as "daft" in The Guardian, and the result disputed by Anglicans and Catholics.[40][41] Historians had nominated one person per century, and for the 12th century John Hudson chose Becket for being "greedy", "hypocritical", "founder of gesture politics" and "master of the soundbite".[40] The magazine editor suggested most other nominees were too obscure for voters, as well as saying, "In an era when thumbscrews, racks and burning alive could be passed off as robust law and order—being guilty of 'gesture politics' might seem something of a minor charge."[40]

- The many UK churches dedicated to Thomas Becket include Cathedral Church of St Thomas of Canterbury, Portsmouth, St Thomas of Canterbury Church, Canterbury,[42] Church of St Thomas the Martyr, Monmouth,[43] St Thomas à Becket Church, Pensford,[44] St Thomas à Becket Church, Widcombe,[45] Church of St Thomas à Becket, Capel,[46] St Thomas the Martyr, Bristol,[47] and St Thomas the Martyr's Church, Oxford.[48] Those in France include Église Saint-Thomas de Cantorbéry at Mont-Saint-Aignan, Upper-Normandy,[49] Église Saint-Thomas-Becket at Gravelines (Nord-Pas-de-Calais), Église Saint-Thomas Becket at Avrieux (Rhône-Alpes), and Église saint-Thomas Becket at Bénodet (Brittany),[50]

- Among his obligations in contrition to Henry, William de Tracy much enlarged and re-dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury the parish church in Lapford, Devon, in his manor of Bradninch. The martyrdom day is still marked by a Lapford Revel.

- British schools named after Thomas Becket include Becket Keys Church of England School and St Thomas of Canterbury Church of England Aided Junior School.

- Part of the Hungarian city of Esztergom is named Szenttamás ("Saint Thomas"), on a hill called "Szent Tamás" dedicated to Thomas Becket – a classmate of Lucas, Archbishop of Esztergom in Paris.[51]

- In the treasury of Fermo Cathedral is the Fermo chasuble of St. Thomas Becket, on display at Museo Diocesano

- Thomas Becket is honoured in the Church of England and in the Episcopal Church on 29 December.[52][53]

Wall painting of Thomas Becket's martyrdom painted in the 1330s in the parish church of St Peter ad Vincula, South Newington, Oxfordshire

Wall painting of Thomas Becket's martyrdom painted in the 1330s in the parish church of St Peter ad Vincula, South Newington, Oxfordshire The coat of arms of the City of Canterbury combines the attributed arms of Thomas Becket (three Cornish choughs) with a lion from the royal arms of England

The coat of arms of the City of Canterbury combines the attributed arms of Thomas Becket (three Cornish choughs) with a lion from the royal arms of England

See also

- Saint Thomas Becket, patron saint archive

Explanatory notes

- The name "Thomas à Becket" is not contemporary. It appears to be a post-Reformation creation, possibly modelled on Thomas à Kempis.[2]

- There is a legend that claims Thomas's mother was a Saracen princess who met and fell in love with his English father while he was on Crusade or pilgrimage in the Holy Land, followed him home, was baptised and married him. This story has no truth to it, being a fabrication from three centuries after the saint's martyrdom, inserted as a forgery into Edward Grim's 12th-century Life of St Thomas.[5][6] Matilda is occasionally known as Rohise.[1]

References

Footnotes

- Barlow "Becket, Thomas (1120?–1170)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Barlow Thomas Becket pp. 11–12.

- Barlow Thomas Becket pp. 3–9.

- Butler and Walsh Butler's Lives of the Saints p. 430

- Staunton Lives of Thomas Becket p. 29.

- Hutton Thomas Becket – Archbishop of Canterbury p. 4.

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 84.

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 192–195.

- "V&A plaque", with latest count; Binski, 225, with a catalogue entry on one in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

- Warren, W.L. (1973). Henry II. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 507. ISBN 9780520034945.

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 194.

- Warren Henry II p. 508.

- Jonathan McGovern, 'The Origin of the Phrase "Will No One Rid Me of this Turbulent Priest?"', Notes and Queries (2021). DOI: 10.1093/notesj/gjab094; Knowles Oxford Dictionary of Quotations p. 370

- Schama History of Britain p. 142.

- Stanley Historical Memorials of Canterbury pp. 53–55.

- Wilkes, Aaron (2019). "Crown vs Church: Murder in the Cathedral". Invasion, Plague and Murder: Britain 1066-1558. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-849464-5.

- Lee This Sceptred Isle p. 97.

- Forester, Thomas (2001). Giraldus Cambrensis – The Conquest of Ireland. Cambridge, Ontario: In Parentheses Publications.

- Grim, Benedict of Peterborough and William fitzStephen are quoted in Douglas, et al. English Historical Documents 1042–1182 Vol. 2, p. 821.

- William Page & J. Horace Round, ed. (1907). 'Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey of Barking', A History of the County of Essex: Volume 2. pp. 115–122.

- Barlow Thomas Becket pp. 257–258.

- Drake, Gavin (23 May 2016). "Becket's bones return to Canterbury Cathedral". anglicannews.org. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Sánchez, Carles (2021). A painted tragedy The martyrdom of Thomas Becket in Santa Maria de Terrassa and the diffusion of its cult in the Iberian Peninsula. Anem Editors. ISBN 978-84-122385-7-0.

- Reames, Sherry L. (January 2005). "Reconstructing and Interpreting a Thirteenth-Century Office for the Translation of Thomas Becket". Speculum. 80 (1): 118–170. doi:10.1017/S0038713400006679. JSTOR 20463165. S2CID 162716876. Quoting pp. 118–119.

- Scully, Robert E. (October 2000). "The Unmaking of a Saint: Thomas Becket and the English Reformation". The Catholic Historical Review. 86 (4): 579–602. doi:10.1353/cat.2000.0094. JSTOR 25025818. S2CID 201743927. Especially p. 592.

- "The Origins of Canterbury Cathedral". Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "The Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket (Getty Museum)". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007.

- Harvey, Katherine (January 2019). "The Cult of Thomas Becket: History and Historiography through Eight Centuries | Reviews in History". Reviews in History. doi:10.14296/RiH/2014/2303. S2CID 193137069. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Enciclopedia del románico en Castilla y León: Soria III. Fundación Santa María la Real – Centro de Estudios del Románico, pp. 961, 1009–1017.

- "St Thomas Becket landing at Sandwich (Relief)". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "St Thomas Becket meeting the Pope (Panel)". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Consecration of St Thomas Becket as archbishop (Panel)". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Canterbury (England) – Coat of arms". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- Child, Harold Hannyngton (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Malvern, Jack (10 June 2006). "Hollywood shines a light on geezers who killed à Becket". The Times. London. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "Troubled Bones".

- Hughes, Peter (26 May 2000). "Music festivals: We pick 10 of the best". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Reeves, David; Bowman, James; Wilson-Johnson, David; Neary, Martin; Slane, Phillip; Novis, Constance; Brink, Harvey; Keith, Gillian; Willocks, David; English Chamber Choir; English Festival Orchestra (1999), Becket: The kiss of peace=Le baiser de la paix=Der Kuss der Friedens, English Gramophone/DRM Control Point; Australia: manufactured in Australia under license, retrieved 3 July 2018

- "Becket Fund". Becket Fund. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Coughlan, Sean (31 January 2006). "UK | Saint or sinner?". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Weaver, Matthew (31 January 2006). "Asking silly questions". The Guardian. London. News Blog. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "Portsmouth Cathedral, St Thomas' Cathedral, Old Portsmouth". Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Welcome to Monmouth, St Thomas Church Monmouth". Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "South West England". Heritage at Risk. English Heritage. p. 243. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Historic England. "Church of St Thomas a Becket (1394116)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Church of St Thomas a Becket, Capel, Kent". Churches Conservation Trust. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Church of St Thomas the Martyr, Bristol". Churches Conservation Trust. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "St Thomas the Martyr, Oxford". A Church Near You. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Saint-Thomas de Cantorbéry". Mondes-normands.caen.fr. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Saint-Thomas Becket (Bénodet)". Linternaute.com. 18 March 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Györffy, György (1970). "Becket Tamás és Magyarország [Thomas Becket and Hungary]". Filológiai Közlöny. 16 (1–2): 153–158. ISSN 0015-1785.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

Bibliography

- Barlow, Frank (1986). Thomas Becket. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07175-9.

- Barlow, Frank (2004). "Becket, Thomas (1120?–1170)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27201. Retrieved 17 April 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Butler, Alban (1991). Walsh, Michael (ed.). Butler's Lives of the Saints. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Douglas, David C.; Greenway, George W. (1953). English Historical Documents 1042–1189. Vol. 2 (Second, 1981 ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14367-7.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- Hutton, William Holden (1910). Thomas Becket – Archbishop of Canterbury. London: Pitman and Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4097-8808-9.

- Knowles, Elizabeth M. (1999). Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (Fifth ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860173-9.

- Lee, Christopher (2012). This Sceptred Isle: The Making of the British. Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84901-939-2.

- Robertson, James Craigie (1876). Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. Vol. ii. London: Longman.

- Schama, Simon (2002). A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World? : 3000 BC–AD 1603. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-38497-7.

- Stanley, Arthur Penrhyn (1855). Historical Memorials of Canterbury. London: John Murray.

- Staunton, Michael (2001). The Lives of Thomas Becket. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719054549.

- Staunton, Michael (2006). Thomas Becket and His Biographers. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-271-3.

- Warren, W. L. (1973). Henry II. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03494-5.

Further reading

Biographies

- Anne Duggan, 2005, Thomas Becket, London: Hodder Arnold

- John Guy, 2012, Thomas Becket: Warrior, Priest, Rebel, Random House

- David Knowles 1970, Thomas Becket, London: Adam & Charles Black

- Richard Winston, 1967, Thomas Becket, New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Historiography

- James W. Alexander, "The Becket controversy in recent historiography", Journal of British studies 9.2 (1970): 1-26. in JSTOR

- Anne Duggan, 1980, Thomas Becket: A Textual History of his Letters, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Anne Duggan, ed., 2000, The Correspondence of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury (1162–1170). 2 vols, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Carles Sánchez Márquez, 2021, A painted tragedy. The martyrdom of Thomas Becket in Santa Maria de Terrassa and the diffusion of its cult in the Iberian Peninsula, La Seu d'Urgell: Anem Editors

External links

- Portraits of Thomas Becket at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Edward Grim’s account of the murder of Thomas Becket at Internet History Sourcebooks Project

- Beckets Bits, photographs and locations of twenty of the surviving medieval Limoges enamel chasses for relics of Becket

- Daily Telegraph:On this day in 1170: Thomas Becket is murdered in Canterbury Cathedral, and becomes a martyr

- BBC In Our Time: Thomas Becket