Sun Salutation

Sun Salutation, also called Surya Namaskar(a) or Salute to the Sun[2] (Sanskrit: सूर्यनमस्कार, romanized: Sūryanamaskāra),[3] is a practice in yoga as exercise incorporating a flow sequence of some twelve gracefully linked asanas.[4][5] The asana sequence was first recorded as yoga in the early 20th century, though similar exercises were in use in India before that, for example among wrestlers. The basic sequence involves moving from a standing position into Downward and Upward Dog poses and then back to the standing position, but many variations are possible. The set of 12 asanas is dedicated to the Hindu solar deity, Surya. In some Indian traditions, the positions are each associated with a different mantra.

.jpg.webp)

The precise origins of the Sun Salutation are uncertain, but the sequence was made popular in the early 20th century by Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi, the Rajah of Aundh, and adopted into yoga by Krishnamacharya in the Mysore Palace, where the Sun Salutation classes, not then considered to be yoga, were held next door to his yogasala. Pioneering yoga teachers taught by Krishnamacharya, including Pattabhi Jois and B. K. S. Iyengar, taught transitions between asanas derived from the Sun Salutation to their pupils worldwide.

Etymology and origins

The name Surya Namaskar is from the Sanskrit सूर्य Sūrya, "Sun" and नमस्कार Namaskāra, "Greeting" or "Salute".[8] Surya is the Hindu demigod of the sun.[9] This identifies the Sun as the soul and source of all life.[10] Chandra Namaskara is similarly from Sanskrit चन्द्र Chandra, "Moon".[11]

The origins of the Sun Salutation are vague; Indian tradition connects the 17th century saint Samarth Ramdas with Surya Namaskara exercises, without defining what movements were involved.[12] In the 1920s, Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi, the Rajah of Aundh, popularized and named the practice, describing it in his 1928 book The Ten-Point Way to Health: Surya Namaskars.[6][7][13][14] It has been asserted that Pant Pratinidhi invented it,[15] but Pant stated that it was already a commonplace Marathi tradition.[16]

Ancient but simpler Sun salutations such as Aditya Hridayam, described in the "Yuddha Kaanda" Canto 107 of the Ramayana,[17][18][19] are not related to the modern sequence.[20] The anthropologist Joseph Alter states that the Sun Salutation was not recorded in any Haṭha yoga text before the 19th century.[21] At that time, the Sun Salutation was not considered to be yoga, and its postures were not considered asanas; the pioneer of yoga as exercise, Yogendra, wrote criticising the "indiscriminate" mixing of sun salutation with yoga as the "ill-informed" were doing.[7]

The yoga scholar-practitioner Norman Sjoman suggested that Krishnamacharya, "the father of modern yoga",[23][24] used the traditional and "very old"[25] Indian wrestlers' exercises called dandas (Sanskrit: दण्ड daṇḍa, a staff), described in the 1896 Vyayama Dipika,[26] as the basis for the sequence and for his transitioning vinyasas.[25] Different dandas closely resemble the Sun Salutation asanas Tadasana, Padahastasana, Caturanga Dandasana, and Bhujangasana.[25] Krishnamacharya was aware of the Sun Salutation, since regular classes were held in the hall adjacent to his Yogasala in the Rajah of Mysore's palace.[27] The yoga scholar Mark Singleton states that "Krishnamacharya was to make the flowing movements of sūryanamaskār the basis of his Mysore yoga style".[28] His students, K. Pattabhi Jois,[29] who created modern day Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga,[30] and B. K. S. Iyengar, who created Iyengar Yoga, both learned Sun Salutation and flowing vinyasa movements between asanas from Krishnamacharya and used them in their styles of yoga.[27]

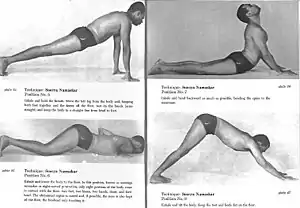

The historian of modern yoga Elliott Goldberg writes that Vishnudevananda's 1960 book The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga "proclaimed in print" a "new utilitarian conception of Surya Namaskara"[22][31] which his guru Sivananda had originally promoted as a health cure through sunlight. Goldberg notes that Vishnudevananda modelled the positions of the Sun Salutation for photographs in the book, and that he recognised the sequence "for what it mainly is: not treatment for a host of diseases but fitness exercise."[22]

Description

Sun Salutation is a sequence of around twelve yoga asanas connected by jumping or stretching movements, varying somewhat between schools. In Iyengar Yoga, the basic sequence is Tadasana, Urdhva Hastasana, Uttanasana, Uttanasana with head up, Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Dog), Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Upward Dog), Chaturanga Dandasana, and then reversing the sequence to return to Tadasana; other poses can be inserted into the sequence.[8]

In Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, there are two Sun Salutation sequences, types A and B.[32] The type A sequence of asanas is Pranamasana, Urdhva Hastasana, Uttanasana, Phalakasana (high plank), Chaturanga Dandasana, Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, Adho Mukha Svanasana, Uttanasana and back to Pranamasana.[32] The type B sequence of asanas (differences marked in italics) is Pranamasana, Utkatasana, Uttanasana, Ardha Uttanasana, Phalakasana, Chaturanga Dandasana, Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, Adho Mukha Svanasana, Virabhadrasana I, repeat from Phalakasana onwards with Virabhadrasana I on the other side, then repeat Phalakasana through to Adho Mukha Svanasana (a third time), Ardha Uttanasana, Uttanasana, Utkatasana, and back to Pranamasana.[32]

A typical[lower-alpha 2] Sun Salutation cycle is:

1: Pranamasana |  2: Hasta Uttanasana |  3. Uttanasana | ||

12: Back to 1 | .JPG.webp) 4. Anjaneyasana | |||

11. Hasta Uttanasana |  5. Adho Mukha Svanasana | |||

10. Uttanasana |  6. Ashtanga Namaskara | |||

.JPG.webp) 9. Anjaneyasana, opposite foot |  8. Adho Mukha Svanasana |  7.Urdhva Mukha Shvanasana |

Mantras

In some yoga traditions, each step of the sequence is associated with a mantra. In traditions including Sivananda Yoga, the steps are linked with twelve names of the God Surya, the Sun:[33]

| Step (Asana) | Mantra (name of Surya)[33] | Translation: Om, greetings to the one who ...[33] |

|---|---|---|

| Tadasana | ॐ मित्राय नमः Oṃ Mitrāya Namaḥ | is affectionate to all |

| Urdhva Hastasana | ॐ रवये नमः Oṃ Ravaye Namaḥ | is the cause of all changes |

| Padahastasana | ॐ सूर्याय नमः Oṃ Sūryāya Namaḥ | induces all activity |

| Ashwa Sanchalanasana | ॐ भानवे नमः Oṃ Bhānave Namaḥ | diffuses light |

| Parvatasana | ॐ खगाय नमः Oṃ Khagāya Namaḥ | moves in the sky |

| Ashtanga Namaskara | ॐ पूष्णे नमः Oṃ Pūṣṇe Namaḥ | nourishes all |

| Bhujangasana | ॐ हिरण्यगर्भाय नमः Oṃ Hiraṇya Garbhāya Namaḥ | contains the golden rays |

| Parvatasana | ॐ मरीचये नमः Oṃ Marīcaye Namaḥ | possesses raga |

| Ashwa Sanchalanasana | ॐ आदित्याय नमः Oṃ Ādityāya Namaḥ | is son of Aditi |

| Padahastasana | ॐ सवित्रे नमः Oṃ Savitre Namaḥ | produces everything |

| Urdhva Hastasana | ॐ अर्काय नमः Oṃ Arkāya Namaḥ | is fit to be worshipped |

| Tadasana | ॐ भास्कराय नमः Oṃ Bhāskarāya Namaḥ | is the cause of lustre |

Indian tradition associates the steps with Bījā ("seed" sound) mantras and with five chakras (focal points of the subtle body).[34][35]

| Step (Asana) | Bījā mantra[35][34][lower-alpha 3] | Chakra[35] | Breathing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tadasana | ॐ ह्रां Oṃ Hrāṁ | Anahata (heart) | exhale |

| Urdhva Hastasana | ॐ ह्रीं Oṃ Hrīṁ | Vishuddhi (throat) | inhale |

| Padahastasana | ॐ ह्रूं Oṃ Hrūṁ | Swadhisthana (sacrum) | exhale |

| Ashwa Sanchalanasana | ॐ ह्रैं Oṃ Hraiṁ | Ajna (third eye) | inhale |

| Parvatasana | ॐ ह्रौं Om Hrauṁ | Vishuddhi (throat) | exhale |

| Ashtanga Namaskara | ॐ ह्रः Oṃ Hraḥ | Manipura (solar plexus) | suspend |

| Bhujangasana | ॐ ह्रां Oṃ Hrāṁ | Swadhisthana (sacrum) | inhale |

| Parvatasana | ॐ ह्रीं Oṃ Hrīṁ | Vishuddhi (throat) | exhale |

| Ashwa Sanchalanasana | ॐ ह्रूं Oṃ Hrūṁ | Ajna (third eye) | inhale |

| Padahastasana | ॐ ह्रैं Oṃ Hraiṁ | Swadhisthana (sacrum) | exhale |

| Urdhva Hastasana | ॐ ह्रौं Oṃ Hrauṁ | Vishuddhi (throat) | inhale |

| Tadasana | ॐ ह्रः Oṃ Hraḥ | Anahata (heart) | exhale |

Variations

Inserting other asanas

Many variations are possible. For example, in Iyengar Yoga the sequence may intentionally be varied to run Tadasana, Urdhva Hastasana, Uttanasana, Adho Mukha Svanasana, Lolasana, Janusirsasana (one side, then the other), and reversing the sequence from Adho Mukha Svanasana to return to Tadasana. Other asanas that may be inserted into the sequence include Navasana (or Ardha Navasana), Paschimottanasana and its variations, and Marichyasana I.[8]

Chandra Namaskara

Variant sequences named Chandra Namaskar, the Moon Salutation, are sometimes practised; these were created late in the 20th century.[37] One such sequence consists of the asanas Tadasana, Urdhva Hastasana, Anjaneyasana (sometimes called Half Moon Pose), a kneeling lunge, Adho Mukha Svanasana, Bitilasana, Balasana, kneeling with thighs, body, and arms pointing straight up, Balasana with elbows on ground, hands together in Anjali Mudra behind the head, Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, Adho Mukha Svanasana, Uttanasana, Urdhva Hastasana, Pranamasana, and Tadasana.[38] Other Moon Salutations with different asanas have been published.[37][39][40]

As exercise

The energy cost of exercise is measured in units of metabolic equivalent of task (MET). Less than 3 METs counts as light exercise; 3 to 6 METs is moderate; 6 or over is vigorous. American College of Sports Medicine and American Heart Association guidelines count periods of at least 10 minutes of moderate MET level activity towards their recommended daily amounts of exercise.[41][42] For healthy adults aged 18 to 65, the guidelines recommend moderate exercise for 30 minutes five days a week, or vigorous aerobic exercise for 20 minutes three days a week.[42]

The Sun Salutation's energy cost ranges widely according to how energetically it is practised, from a light 2.9 to a vigorous 7.4 METs. The higher end of the range requires transition jumps between the poses.[lower-alpha 4][41]

Muscle usage

A 2014 study indicated that the muscle groups activated by specific asanas varied with the skill of the practitioners, from beginner to instructor. The eleven asanas in the Sun Salutation sequences A and B of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga were performed by beginners, advanced practitioners and instructors. The activation of 14 groups of muscles was measured with electrode on the skin over the muscles. Among the findings, beginners used pectoral muscles more than instructors, whereas instructors used deltoid muscles more than other practitioners, as well as the vastus medialis (which stabilises the knee). The yoga instructor Grace Bullock writes that such patterns of activation suggest that asana practice increases awareness of the body and the patterns in which muscles are engaged, making exercise more beneficial and safer.[43][44]

In culture

The founder of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, K. Pattabhi Jois, stated that "There is no Ashtanga yoga without Surya Namaskara, which is the ultimate salutation to the Sun god."[45]

In 2019, a team of mountaineering instructors from Darjeeling climbed to the summit of Mount Elbrus and completed a Sun Salutation there at 18,600 feet (5,700 m), claimed as a world record.[46]

See also

- Sun worship in Hinduism

- List of solar deities in Hinduism

- List of Hindu Sun temples

- List of Hindu deities

Notes

- Incorporating Ashtanga Namaskara in place of Caturanga Dandasana

- As shown in the Indira Gandhi Airport sculpture, above.

- The Bījā mantras are sounds, not translatable words.[36]

- Haskell, curious about the wide range of METs in Sun Salutation, repeated the study (Mody) which gave the highest value; using "transition jumps, and full pushups", he obtained "agreement" with 6.4 METs.[42]

References

- "Destination Delhi". Indian Express. 4 September 2010.

- "Surya Namaskara Salute to the Sun". Yoga in Daily Life. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Singh, Kritika. Sun Salutation: Full step by step explanation. Surya Namaskar Organization.

- Mitchell, Carol (2003). Yoga on the Ball. Inner Traditions. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-89281-999-7.

- MacMullen, Jane (1988). "Ashtanga Yoga". Yoga Journal. September/October: 68–70.

- Pratinidhi, Pant (1928). The Ten-Point Way to Health | Surya Namaskars. J. M. Dent and Sons. pp. 113–115 and whole book.

The ten positions of a Namaskar are repeated here and may be detached without damaging the book. The pages are perforated for easy removal.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 180–181, 205–206.

- Mehta 1990, pp. 146–147.

- Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Krishan Kumar Suman (2006). Yoga for Health and Relaxation. Lotus. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-81-8382-049-3.

- Sinha, S. C. (1 June 1996). Dictionary of Philosophy. Anmol Publications. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7041-293-9.

- Hindu Vishva. Vol. 15. 1980. p. 27.

Sri Samarath Ramdas Swami took Surya Namaskar exercises with the Mantras as part of his Sadhana.

- S. P. Sen, Dictionary of National Biography; Institute of Historical Studies, Calcutta 1972 Vols. 1–4; Institute of Historical Studies, Vol 3, page 307

- Alter 2000, p. 99.

- Alter 2004, p. 163.

- Singleton 2010, p. 124.

- Murugan, Chillayah (13 October 2016). "Surya Namaskara — Puranic origins of Valmiki Ramayana in the Mumbai Court order on Surya Namaskar for Interfaith discrimination and curtailment of fundamental rights". The Milli Gazette-Indian Muslim Newspaper. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- sanskrit.safire.com, Aditya Hrudayam with English translation

- Translation of Ramayana by Griffith

- Mujumdar 1950.

- Alter 2004, p. 23.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 329–331.

- Mohan, A. G.; Mohan, Ganesh (29 November 2009). "Memories of a Master". Yoga Journal.

- Anderson, Diane (9 August 2010). "The YJ Interview: Partners in Peace". Yoga Journal.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 54.

- Bharadwaj, S. (1896). Vyayama Dipika | Elements of Gymnastic Exercises, Indian System. Bangalore: Caxton Press. pp. Chapter 2.

- Singleton 2010, p. 175-210.

- Singleton 2010, p. 180.

- Donahaye, Guy (2010). Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K Pattabhi Jois Through The Eyes of His Students. USA: D&M Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86547-749-0.

- Ramaswami 2005, pp. 213–219.

- Vishnudevananda 1988.

- Hughes, Aimee. "Sun Salutation A Versus Sun Salutation B: The Difference You Should Know". Yogapedia.

- "Surya Namaskara". Divine Life Society. 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Omar, Shazia (27 December 2016). "Sonic salutations to the sun". Daily Star.

- Hardowar, Radha (June 2018). "Surya Namaskar" (PDF). Shri Surya Narayan Mandir.

- Woodroffe, Sir John (2009) [1919]. ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA (3rd ed.). Celephaïs Press. p. 456.

ŚAKTI AS MANTRA intoned in the proper way, according to both sound (Varṇ a) and rhythm (Svara). For these reasons, a Mantra when translated ceases to be such, and becomes a mere word or sentence. By Mantra, the sought-for (Sādhya) Devatb appears, and by Siddhi therein it had vision of the three worlds. As the Mantra is in fact Devatā, by practice thereof this is known. Not merely do the rhythmical vibrations of its sounds regulate the unsteady vibrations of the sheaths of the worshipper, but therefrom the image of the Devatā, appears. As the Bṛ had-Gandharva Tantra says (Ch. V):— Śrinu devi pravakṣ yāmi bījānām deva-rūpatām Mantroccāranamātrena deva-rūpam prajāyate.

- Ferretti, Andrea; Rea, Shiva (1 March 2012). "Soothing Moon Shine: Chandra Namaskar". Yoga Journal.

- Mirsky, Karina. "A Meditative Moon Salutation". Yoga International. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Venkatesan, Supriya. "Moon Salutations". Yoga U. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Tomlinson, Kirsty. "Moon Salutation sequence". Ekhart Yoga. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Larson-Meyer, D. Enette (2016). "A Systematic Review of the Energy Cost and Metabolic Intensity of Yoga". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 48 (8): 1558–1569. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000922. ISSN 0195-9131. PMID 27433961. The review examined 17 studies, of which 10 measured the energy cost of yoga sessions.

- Haskell, William L.; et al. (2007). "Physical Activity and Public Health". Circulation. 116 (9): 1081–1093. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 17671237.

- Ni, Meng; Mooney, Kiersten; Balachandran, Anoop; Richards, Luca; Harriell, Kysha; Signorile, Joseph F. (2014). "Muscle utilization patterns vary by skill levels of the practitioners across specific yoga poses (asanas)". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 22 (4): 662–669. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2014.06.006. ISSN 0965-2299. PMID 25146071.

- Bullock, B. Grace (2016). "Which Muscles Are You Using in Your Yoga Practice? A New Study Provides the Answers". Yoga U. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Surya Namaskar in the words of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois". Discover the Purpose. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Suryanamaskar and Yoga Atop of Mountain Summit (18600 Feet)". World Records India. 3 October 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019.

Sources

- Alter, Joseph S. (2000). Gandhi's Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-812-23556-2.

- ——— (2004). Yoga in modern India : the body between science and philosophy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11874-1. OCLC 53483558.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0863184208.

- Mujumdar, Dattatraya Chintaman, ed. (1950). Encyclopedia of Indian Physical Culture: A Comprehensive Survey of the Physical Education in India, Profusely Illustrating Various Activities of Physical Culture, Games, Exercises, Etc., as Handed Over to Us from Our Fore-fathers and Practised in India. Good Companions.

- Ramaswami, Srivatsa (2005). The Complete Book of Vinyasa Yoga. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-56924-402-9.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 180–181, 205–206. ISBN 978-0-19-974598-2.

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.

- Vishnudevananda (1988) [1960]. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. New York: Three Rivers Press/Random House. ISBN 0-517-88431-3. OCLC 32442598.

_from_Jogapradipika_1830_(detail).jpg.webp)