Sympathomimetic drug

Sympathomimetic drugs (also known as adrenergic drugs and adrenergic amines) are stimulant compounds which mimic the effects of endogenous agonists of the sympathetic nervous system. Examples of sympathomimetic effects include increases in heart rate, force of cardiac contraction, and blood pressure.[1] The primary endogenous agonists of the sympathetic nervous system are the catecholamines (i.e., epinephrine [adrenaline], norepinephrine [noradrenaline], and dopamine), which function as both neurotransmitters and hormones. Sympathomimetic drugs are used to treat cardiac arrest and low blood pressure, or even delay premature labor, among other things.

These drugs can act through several mechanisms, such as directly activating postsynaptic receptors, blocking breakdown and reuptake of certain neurotransmitters, or stimulating production and release of catecholamines.

Mechanisms of action

The mechanisms of sympathomimetic drugs can be direct-acting (direct interaction between drug and receptor), such as α-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic agonists, and dopaminergic agonists; or indirect-acting (interaction not between drug and receptor), such as MAOIs, COMT inhibitors, release stimulants, and reuptake inhibitors that increase the levels of endogenous catecholamines.

Structure-activity relationship

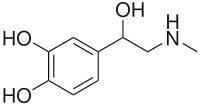

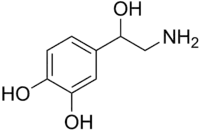

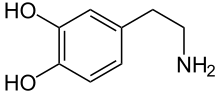

For maximum sympathomimetic activity, a drug must have:

- Amine group two carbons away from an aromatic group

- A hydroxyl group at the chiral beta position in the R-configuration

- Hydroxyl groups in the meta and para position of the aromatic ring to form a catechol which is essential for receptor binding

The structure can be modified to alter binding. If the amine is primary or secondary, it will have direct action, but if the amine is tertiary, it will have poor direct action. Also, if the amine has bulky substituents, then it will have greater beta adrenergic receptor activity, but if the substituent is not bulky, then it will favor the alpha adrenergic receptors.

Adrenergic receptor agonists

Direct stimulation of the α- and β-adrenergic receptors can produce sympathomimetic effects. Salbutamol is a widely used direct-acting β2-agonist. Other examples include phenylephrine, isoproterenol, and dobutamine.

Dopaminergic agonists

Stimulation of the D1 receptor by dopaminergic agonists such as fenoldopam is used intravenously to treat hypertensive crisis.

Indirect-acting

Dopaminergic stimulants such as amphetamine, ephedrine, and propylhexedrine work by causing the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, along with (in some cases) blocking the reuptake of these neurotransmitters.

Structure-activity relationship

A primary or secondary aliphatic amine separated by 2 carbons from a substituted benzene ring is minimally required for high agonist activity. The pKa of the amine is approximately 8.5-10.[2] The presence of hydroxy group in the benzene ring at 3rd and 4th position shows maximum alpha- and beta-adrenergic activity.

Cross-reactivity

Illegal drugs such as cocaine and MDMA also affect dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine.

Norepinephrine is synthesized by the body from the amino acid tyrosine,[3] and is used in the synthesis of epinephrine, which is a stimulating neurotransmitter of the central nervous system.[4] Thus, all sympathomimetic amines fall into the larger group of stimulants (see psychoactive drug chart). In addition to intended therapeutic use, many of these stimulants have abuse potential, can induce tolerance, and possibly physical dependence, although not by the same mechanism(s) as opioids or sedatives. The symptoms of physical withdrawal from stimulants can include fatigue, dysphoric mood, increased appetite, vivid or lucid dreams, hypersomnia or insomnia, increased movement or decreased movement, anxiety, and drug craving, as is apparent in the rebound withdrawal from certain substituted amphetamines. Physical withdrawal from some sedatives can be potentially lethal, for instance benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Opioid withdrawal is very uncomfortable, often described as a bad case of the flu, with possibly severe abdominal cramps and diarrhoea as central symptoms,[5] but it is rarely lethal unless the user has a comorbid condition.[6]

Sympathomimetic drugs are sometimes involved in development of cerebral vasculitis and generalized polyarteritis nodosa like diseases involving immune-complex deposition. Known reports of such hypersensitivity reactions include the use of pseudoephedrine,[7] phenylpropanlolamine,[8] methamphetamine[9] and other drugs at prescribed doses as well as at over-doses.

Comparison

"Parasympatholytic" and "sympathomimetic" have similar effects, but through completely different pathways. For example, both cause mydriasis, but parasympatholytics reduce accommodation (cycloplegia) while sympathomimetics do not.

Examples

- amphetamine (Evekeo)

- benzylpiperazine (BZP)

- cathine (found in Catha edulis)

- cathinone (found in Catha edulis, khat)

- cocaine (found in Erythroxylum coca, coca)

- ephedrine (found in Ephedra)

- lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse)

- maprotiline (Ludiomil)

- MDMA (Ecstasy, Molly)

- methamphetamine (Meth, Crank, Desoxyn)

- methcathinone

- methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)

- methylphenidate (Ritalin)

- 4-methylaminorex

- oxymetazoline (Afrin, Vicks Sinex)

- pemoline (Cylert)

- phenmetrazine (Preludin)

- propylhexedrine (Benzedrex)

- pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, SudoGest, also found in Ephedra species)

Benzphetamine (Didrex)

See also

- Adrenergic storm

- Sympathetic nervous system

- Sympatholytic

References

- Ellie Kirov (9 November 2021). Herlihy's the Human Body in Health and Illness 1st Anz Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 234–. ISBN 978-0-7295-8853-9. OCLC 1287761421.

If a drug causes effects similar to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, it is called a sympathomimetic [...] A sympathomimetic agent increases heart rate, force of cardiac contraction and blood pressure.

- Medicinal Chemistry of Adrenergics and Cholinergics Archived 2010-11-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (7th ed.). Pearson - Benjamin Cummings.

- Patestas, Maria A.; Gartner, Leslie P. (2006). A Textbook of Neuroanatomy. Blackwell Publishing.

- Longmore, Murray; Wilkinson, Ian B.; Davidson, Edward H.; Foulkes, Alexander; Mafi, Ahmad R. (2008). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (8th ed.). OUP Oxford.

- "Medscape Opioid Abuse, Treatment and Management".

- "Pseudoephedrine Disease Interactions". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- Forman, Howard P.; Levin, Stanley; Stewart, Barbara; Patel, Mahendra; Feinstein, Stuart (1989-05-01). "Cerebral Vasculitis and Hemorrhage in an Adolescent Taking Diet Pills Containing Phenylpropanolamine: Case Report and Review of Literature". Pediatrics. 83 (5): 737–741. doi:10.1542/peds.83.5.737. ISSN 0031-4005.

- Imbesi, S G (December 1999). "Diffuse cerebral vasculitis with normal results on brain MR imaging". American Journal of Roentgenology. 173 (6): 1494–1496. doi:10.2214/ajr.173.6.10584789. ISSN 0361-803X.

External links

- Amines,+Sympathomimetic at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)