Varenicline

Varenicline (trade name Chantix and Champix) is a medication used for smoking cessation.[4][6] Varenicline is also used for the treatment of dry eye disease.[5][7]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Champix, Chantix, Tyrvaya, others |

| Other names | OC-01 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a606024 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, Nasal spray |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <20% |

| Metabolism | Limited (<10%) |

| Elimination half-life | 24 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (81–92%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

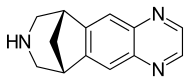

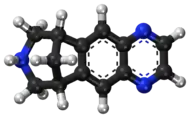

| Formula | C13H13N3 |

| Molar mass | 211.268 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

The most common side-effects include nausea (feeling sick), insomnia (difficulty sleeping), abnormal dreams, headache and nasopharyngitis (inflammation of the nose and throat).[6]

It is a high-affinity partial agonist for the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype (nACh) that leads to the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the nucleus accumbens reward center of the brain when activated, and therefore, has the capacity to reduce the feelings of craving and withdrawal caused by smoking cessation.[8] In this respect it is similar to cytisine and different from the nicotinic antagonist bupropion and nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) like nicotine patches and nicotine gum. It is estimated that varenicline successfully helps one of every eleven people who smoke remain abstinent from tobacco at six months.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10][11] It is available as a generic medication.[12]

Medical uses

Varenicline is used to help people stop smoking tobacco (smoking cessation). A meta-analysis found that less than 20% of people treated with varenicline remain abstinent from smoking at one year.[13] In a 2009 meta-analysis varenicline was found to be more effective than bupropion (odds ratio 1.40) and nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) (odds ratio 1.56).[14]

A 2013 Cochrane overview and network meta-analysis concluded that varenicline is the most effective medication for tobacco cessation and that smokers were nearly three times more likely to quit tobacco use while on varenicline than with placebo treatment. Varenicline was more efficacious than bupropion or NRT and as effective as combination NRT for tobacco smoking cessation.[15][16]

Varenicline has not been tested in those under 18 years old or pregnant women and therefore is not recommended for use by these groups.[17] Varenicline is considered a class C pregnancy drug, as animal studies have shown no increased risk of congenital anomalies; however, no data from human studies is available.[18] An observational study is currently being conducted assessing for malformations related to varenicline exposure, but has no results yet.[19] An alternate drug is preferred for smoking cessation during breastfeeding due to lack of information and based on the animal studies on nicotine.[20]

Side effects

Mild nausea is the most common side effect and is seen in approximately 30% of people taking varenicline though this rarely (<3%) results in discontinuation of the medication.[16] Other less common side effects include headache, difficulty sleeping, and vivid dreams. Rare side effects reported by people taking varenicline compared to placebo include change in taste, vomiting, abdominal pain, flatulence, and constipation. It has been estimated that for every five subjects taking varenicline at maintenance doses, there will be an event of nausea, and for every 24 of 35 treated subjects, there will be an event of constipation and flatulence, respectively. Gastrointestinal side-effects lead to discontinuation of the drug in 2% to 8% of people using varenicline.[21][22] Incidence of nausea is dose-dependent: incidence of nausea was higher in people taking a larger dose (30%) versus placebo (10%) as compared to people taking a smaller dose (16%) versus placebo (11%).[4]

Depression and suicide

In 2007, the US FDA had announced it had received post-marketing reports of thoughts of suicide and occasional suicidal behavior, erratic behavior, and drowsiness among people using varenicline for smoking cessation. In 2009, the US FDA required varenicline to carry a boxed warning that the drug should be stopped if any of these symptoms are experienced.[23]

A 2014 systematic review did not find evidence of an increased suicide risk.[24] Other analyses have reached the same conclusion and found no increased risk of neuropsychiatric side effects with varenicline.[15][16] No evidence for increased risks of cardiovascular events, depression, or self-harm with varenicline versus nicotine replacement therapy was found in one post-marketing surveillance study.[25]

In 2016 the FDA removed the black box warning.[26] People are still advised to stop the medication if they "notice any side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking."[26][27][28]

Cardiovascular disease

In June 2011, the US FDA issued a safety announcement that varenicline may be associated with "a small, increased risk of certain cardiovascular adverse events in people who have cardiovascular disease."[29]

A prior 2011 review had found increased risk of cardiovascular events compared with placebo.[30] Expert commentary in the same journal raised doubts about the methodology of the review,[31][32] concerns which were echoed by the European Medicines Agency and subsequent reviews.[33][34] Of specific concern were "the low number of events seen, the types of events counted, the higher drop-out rate in people receiving placebo, the lack of information on the timing of events, and the exclusion of studies in which no-one had an event."

In contrast, multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found no increase in overall or serious adverse cardiovascular events (including for individuals at risk of developing cardiovascular disease) associated with varenicline use.[34][35][36][37]

Mechanism of action

Varenicline displays full agonism on α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and is a partial agonist on the α4β2, α3β4, and α6β2 subtypes.[38][39][40] In addition, it is a weak agonist on the α3β2 containing receptors.

Varenicline's partial agonism on the α4β2 receptors rather than nicotine's full agonism produces less effect of dopamine release than nicotine's. This α4β2 competitive binding reduces the ability of nicotine to bind and stimulate the mesolimbic dopamine system—similar to the method of action of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

Most of the active compound is excreted by the kidneys (92–93%). A small proportion is glucuronidated, oxidised, N-formylated or conjugated to a hexose.[41] The elimination half-life is about 24 hours.

History

Use of Cytisus plants as a smoking substitutes during World War II[42] led to use as a cessation aid in eastern Europe and extraction of cytisine.[43] Cytisine analogs led to varenicline at Pfizer.[44][45][46]

Varenicline received a "priority review" by the US FDA in February 2006, shortening the usual ten-month review period to six months because of its demonstrated effectiveness in clinical trials and perceived lack of safety issues.[47] The agency's approval of the drug came on May 11, 2006.[48][49] On September 29, 2006, it was approved for sale in the European Union.[6]

On September 16, 2021, Pfizer announced a recall of "all lots of its anti-smoking treatment, Chantix [Varenicline], due to high levels of cancer-causing agents called nitrosamines in the pills".[50] This followed a July 2, 2021 announcement by the FDA that it was "alerting patients and health care professionals to Pfizer's voluntary recall of nine lots of the smoking cessation drug" and further recalls by Pfizer on July 19 and Aug. 8.[51] On June 24, Pfizer had paused distribution of Chantix worldwide;[52] "[t]he distribution halt [wa]s out of an abundance of caution, pending further testing, the company said in an email.[53] According to the Pfizer Inc. 2020 Form 10-K Annual Report, high-revenue products by the company include[d] Chantix/Champix (varenicline) to treat nicotine addiction, [which] had $919 million in 2020 revenues.[54]

In October 2021, US FDA approved Oyster Point Pharma to market Tyrvaya as a new route of varenicline administration through nasal spray for the treatment of dry eye disease.[55]

References

- "Champix Product Information". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 26 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Champix varenicline (as tartrate) 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg tablet blister pack". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Champix 0.5 mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Chantix- varenicline tartrate tablet, film coated Chantix- varenicline tartrate kit". DailyMed. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Tyrvaya- varenicline spray". DailyMed. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- "Champix EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 26 September 2021. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Oyster Point Pharma Announces FDA Approval of Tyrvaya (varenicline solution) Nasal Spray for the Treatment of the Signs and Symptoms of Dry Eye Disease" (Press release). Oyster Point Pharma. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021 – via PR Newswire.

- Tashkin DP (August 2015). "Smoking Cessation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 36 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1555610. PMID 26238637.

- Crawford, P; Cieslak, D (September 2017). "Varenicline for Smoking Cessation". American Family Physician. 96 (5): Online. PMID 28925657.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "Varenicline: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- Rosen LJ, Galili T, Kott J, Goodman M, Freedman LS (May 2018). "Diminishing benefit of smoking cessation medications during the first year: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Addiction. 113 (5): 805–816. doi:10.1111/add.14134. PMC 5947828. PMID 29377409.

- Mills EJ, Wu P, Spurden D, Ebbert JO, Wilson K (September 2009). "Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Harm Reduction Journal. 6: 25. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-25. PMC 2760513. PMID 19761618.

- Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T (May 2013). "Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 5 (5): CD009329. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. PMC 8406789. PMID 23728690.

- Elrashidi MY, Ebbert JO (June 2014). "Emerging drugs for the treatment of tobacco dependence: 2014 update". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs (Review). 19 (2): 243–60. doi:10.1517/14728214.2014.899580. PMID 24654737. S2CID 207484687.

- Claire, Ravinder; Chamberlain, Catherine; Davey, Mary-Ann; Cooper, Sue E.; Berlin, Ivan; Leonardi-Bee, Jo; Coleman, Tim (4 March 2020). "Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD010078. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010078.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7059898. PMID 32129504.

- Cressman AM, Pupco A, Kim E, Koren G, Bozzo P (May 2012). "Smoking cessation therapy during pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician. 58 (5): 525–7. PMC 3352787. PMID 22586193.

- Clinical trial number NCT01290445 for "Varenicline Pregnancy Cohort Study" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- "LactMed". nih.gov.

- Leung LK, Patafio FM, Rosser WW (September 2011). "Gastrointestinal adverse effects of varenicline at maintenance dose: a meta-analysis". BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 11 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-11-15. PMC 3192741. PMID 21955317.

- American Cancer Society. "Cancer Drug Guide: Varenicline". Archived from the original on 2008-06-30. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- FDA. "Public Health Advisory: FDA Requires New Boxed Warnings for the Smoking Cessation Drugs Chantix and Zyban". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- Hughes JR (January 2016). "Varenicline as a Cause of Suicidal Outcomes". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 18 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu275. PMID 25572451.

- Kotz D, Viechtbauer W, Simpson C, van Schayck OC, West R, Sheikh A (October 2015). "Cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric risks of varenicline: a retrospective cohort study". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine (retrospective cohort). 3 (10): 761–8. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00320-3. PMC 4593936. PMID 26355008.

- Food and Drug Administration (16 December 2016). "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion): Drug Safety Communication - Mental Health Side Effects Revised". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Palmer G, Massey V (May 1969). "Electron paramagnetic resonance and circular dichroism studies on milk xanthine oxidase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 244 (10): 2614–20. doi:10.1186/1753-6561-9-S1-A31. PMC 4306032. PMID 4306032.

- Yeung E, Bachi B, Long B, Lee J, Chao Y (2015). "Varenicline and Depression: a Literature Review" (PDF). World Journal of Medical Education and Research. 9 (1): 24–29.

- "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Chantix (varenicline) may increase the risk of certain cardiovascular adverse events in patients with cardiovascular disease". 2011-06-16.

- Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD (September 2011). "Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ. 183 (12): 1359–66. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110218. PMC 3168618. PMID 21727225.

- Takagi H, Umemoto T (September 2011). "Varenicline: quantifying the risk". CMAJ. 183 (12): 1404, author reply 1405, 1407. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111-2063. PMC 3168634. PMID 21896705.

- Samuels L (September 2011). "Varenicline: cardiovascular safety". CMAJ. 183 (12): 1407–8, author reply 1408. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111-2073. PMC 3168639. PMID 21896709.

- "European Medicine Agency confirms positive benefit-risk balance for Champix". 2011-07-21. Archived from the original on 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- Prochaska JJ, Hilton JF (May 2012). "Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 344: e2856. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2856. PMC 3344735. PMID 22563098.

- Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Eapen S, Wu P, Prochaska JJ (January 2014). "Cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies: a network meta-analysis". Circulation (Network Meta-Analysis). 129 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003961. PMC 4258065. PMID 24323793.

- Pipe AL (October 2014). "Network meta-analysis demonstrates the safety of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in cardiovascular patients". Evidence-Based Medicine (Review & Commentary). 19 (5): 193. doi:10.1136/eb-2014-110030. PMID 24917603. S2CID 40856313.

- Rowland K (April 2014). "ACP Journal Club. Review: Nicotine replacement therapy increases CVD events; bupropion and varenicline do not". Annals of Internal Medicine (Review & Commentary). 160 (8): JC2. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-160-8-201404150-02002. PMID 24733219. S2CID 37165486.

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW (September 2006). "Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors". Molecular Pharmacology. 70 (3): 801–5. doi:10.1124/mol.106.025130. PMID 16766716. S2CID 14562170.

- Mineur YS, Picciotto MR (December 2010). "Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 31 (12): 580–6. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004. PMC 2991594. PMID 20965579.

- Bordia T, Hrachova M, Chin M, McIntosh JM, Quik M (August 2012). "Varenicline is a potent partial agonist at α6β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat and monkey striatum". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 342 (2): 327–34. doi:10.1124/jpet.112.194852. PMC 3400806. PMID 22550286.

- Obach RS, Reed-Hagen AE, Krueger SS, Obach BJ, O'Connell TN, Zandi KS, Miller S, Coe JW (January 2006). "Metabolism and disposition of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in vivo and in vitro". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 34 (1): 121–30. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.006767. PMID 16221753. S2CID 18746784.

- Seeger R (January 1992). "[Cytisine as an aid for smoking cessation]". Medizinische Monatsschrift für Pharmazeuten. 15 (1): 20–1. PMID 1542278.

- Prochaska JJ, Das S, Benowitz NL (August 2013). "Cytisine, the world's oldest smoking cessation aid". BMJ. 347: f5198. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5198. PMID 23974638. S2CID 31845933.

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, Sands SB, Davis TI, Lebel LA, Fox CB, Shrikhande A, Heym JH, Schaeffer E, Rollema H, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Chambers LK, Rovetti CC, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, O'Neill BT (May 2005). "Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (10): 3474–7. doi:10.1021/jm050069n. PMID 15887955.

- Schwartz JL (1979). "Review and evaluation of methods of smoking cessation, 1969-77. Summary of a monograph". Public Health Reports. 94 (6): 558–63. PMC 1431736. PMID 515342.

- Etter JF (2006). "Cytisine for smoking cessation: a literature review and a meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (15): 1553–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.15.1553. PMID 16908787.

- Kuehn BM (February 2006). "FDA speeds smoking cessation drug review". JAMA. 295 (6): 614. doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.614. PMID 16467225.

- "FDA Approves Novel Medication for Smoking Cessation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 11 May 2006. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Drug Approval Package: Chantix (Varenicline) NDA #021928". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 June 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Pfizer recalls all lots of anti-smoking drug over carcinogen presence". Reuters. 16 September 2021.

- "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on Nitrosamine in in Varenicline". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 17 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Carcinogen Contamination Halts Sales of Smoking-Cessation Drug". 25 June 2021.

- "Pfizer Pauses Chantix Distribution After Finding Carcinogen". Bloomberg.com. 24 June 2021.

- Harrison, Laird (27 October 2021). "FDA Approves First Nasal Spray for Dry Eye". WenMD Health News. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

External links

- "Varenicline". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Clinical trial number NCT03636061 for "Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of OC-01 Nasal Spray on Signs and Symptoms of Dry Eye Disease (The ONSET-1 Study)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Clinical trial number NCT04036292 for "Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of OC-01 (Varenicline) Nasal Spray on Dry Eye Disease" at ClinicalTrials.gov