Taiko

Taiko (太鼓) are a broad range of Japanese percussion instruments. In Japanese, the term taiko refers to any kind of drum, but outside Japan, it is used specifically to refer to any of the various Japanese drums called wadaiko (和太鼓, lit. "Japanese drums") and to the form of ensemble taiko drumming more specifically called kumi-daiko (組太鼓, lit. "set of drums"). The process of constructing taiko varies between manufacturers, and the preparation of both the drum body and skin can take several years depending on the method.

A chū-daiko, one of many types of taiko | |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | wadaiko, taiko drum |

| Classification | unpitched percussion |

| Developed | Unknown; archaeological evidence shows usage on the Japanese archipelago as early as 6th century CE. |

Taiko have a mythological origin in Japanese folklore, but historical records suggest that taiko were introduced to Japan through Chinese and Korean cultural influence as early as the 6th century CE; pottery from the Haniwa period depicting taiko drums has also been found. Some taiko are similar to instruments originating from India. Archaeological evidence also supports the view that taiko were present in Japan during the 6th century in the Kofun period. Their function has varied throughout history, ranging from communication, military action, theatrical accompaniment, religious ceremony and concert performances. In modern times, taiko have also played a central role in social movements for minorities both within and outside Japan.

Kumi-daiko performance, characterized by an ensemble playing on different drums, was developed in 1951 through the work of Daihachi Oguchi and later in 1961 by the Ondekoza, and taiko was made later popular with many other groups copying the format of Ondekoza such as Kodo, Yamato, Tao, Taikoza, Fuun No Kai, Sukeroku Taiko, etc. Other performance styles, such as hachijō-daiko, have also emerged from specific communities in Japan. Kumi-daiko performance groups are active not only in Japan, but also in the United States, Australia, Canada, Europe, Taiwan, and Brazil. Taiko performance consists of many components in technical rhythm, form, stick grip, clothing, and the particular instrumentation. Ensembles typically use different types of barrel-shaped nagadō-daiko as well as smaller shime-daiko. Many groups accompany the drums with vocals, strings, and woodwind instruments.

History

Origin

The origin of the taiko and its variants is unclear, though there have been many suggestions. Historical accounts, of which the earliest date from 588 CE, note that young Japanese men traveled to Korea to study the kakko, a drum that originated in South China. This study and appropriation of Chinese instruments may have influenced the emergence of taiko.[1] Certain court music styles, especially gigaku and gagaku, arrived in Japan through both China and Korea.[2][3] In both traditions, dancers were accompanied by several instruments that included drums similar to taiko.[3][4] Certain percussive patterns and terminology in togaku, an early dance and music style in Japan, in addition to physical features of the kakko, also reflect influence from both China and India on drum use in gagaku performance.[5][6]

Archaeological evidence shows that taiko were used in Japan as early as the 6th century CE,[7] during the latter part of the Kofun period, and were likely used for communication, in festivals, and in other rituals.[8] This evidence was substantiated by the discovery of haniwa statues in the Sawa District of Gunma Prefecture. Two of these figures are depicted playing drums;[8] one of them, wearing skins, is equipped with a barrel-shaped drum hung from his shoulder and uses a stick to play the drum at hip height.[9][10] This statue is titled "Man Beating the Taiko" and is considered the oldest evidence of taiko performance in Japan.[10][11] Similarities between the playing style demonstrated by this haniwa and known music traditions in China and Korea further suggest influences from these regions.[11]

The Nihon Shoki, the second-oldest book of Japanese classical history, contains a mythological story describing the origin of taiko. The myth tells how Amaterasu, who had sealed herself inside a cave in anger, was beckoned out by an elder goddess Ame-no-Uzume when others had failed. Ame-no-Uzume accomplished this by emptying out a barrel of sake and dancing furiously on top of it. Historians regard her performance as the mythological creation of taiko music.[12]

Use in warfare

In feudal Japan, taiko were often used to motivate troops, call out orders or announcements, and set a marching pace; marches were usually set to six paces per beat of the drum.[13][14] During the 16th-century Warring States period, specific drum calls were used to communicate orders for retreating and advancing.[15] Other rhythms and techniques were detailed in period texts. According to the war chronicle Gunji Yoshū, nine sets of five beats would summon an ally to battle, while nine sets of three beats, sped up three or four times, was the call to advance and pursue an enemy.[16] Folklore from the 16th century on the legendary 6th-century Emperor Keitai offers a story that he obtained a large drum from China, which he named Senjin-daiko (線陣太鼓, "front drum").[17] The Emperor was thought to have used it to both encourage his own army and intimidate his enemies.[17]

In traditional settings

Taiko have been incorporated in Japanese theatre for rhythmic needs, general atmosphere, and in certain settings decoration. In the kabuki play The Tale of Shiroishi and the Taihei Chronicles, scenes in the pleasure quarters are accompanied by taiko to create dramatic tension.[18] Noh theatre also features taiko music,[19][20] where performance consists of highly specific rhythmic patterns. The Konparu (金春流) school of drumming, for example, contains 65 basic patterns in addition to 25 special patterns; these patterns are categorized in several classes.[21] Differences between these patterns include changes in tempo, accent, dynamics, pitch, and function in the theatrical performance. Patterns are also often connected together in progressions.[21]

Taiko continue to be used in gagaku, a classical music tradition typically performed at the Tokyo Imperial Palace in addition to local temples and shrines.[22] In gagaku, one component of the art form is traditional dance, which is guided in part by the rhythm set by the taiko.[23]

Taiko have played an important role in many local festivals across Japan.[24] They are also used to accompany religious ritual music. In kagura, a category of music and dances stemming from Shinto practices, taiko frequently appear alongside other performers during local festivals. In Buddhist traditions, taiko are used for ritual dances as part of the Bon Festival.[25][26] Taiko, along with other instruments, are featured atop towers that are adorned with red-and-white cloth and serve to provide rhythms for the dancers who are encircled around the performers.[27]

Kumi-daiko

In addition to the instruments, the term taiko also refers to the performance itself,[28][29] and commonly to one style called kumi-daiko, or ensemble-style playing (as opposed to festival performances, rituals, or theatrical use of the drums).[30][31] Kumi-daiko was developed by Daihachi Oguchi in 1951.[30][32] He is considered a master performer and helped transform taiko performance from its roots in traditional settings in festivals and shrines.[33] Oguchi was trained as a jazz musician in Nagano, and at one point, a relative gave him an old piece of written taiko music.[34] Unable to read the traditional and esoteric notation,[34] Oguchi found help to transcribe the piece, and on his own added rhythms and transformed the work to accommodate multiple taiko players on different-sized instruments.[35] Each instrument served a specific purpose that established present-day conventions in kumi-daiko performance.[36][37]

Oguchi's ensemble, Osuwa Daiko, incorporated these alterations and other drums into their performances. They also devised novel pieces that were intended for non-religious performances.[34] Several other groups emerged in Japan through the 1950s and 1960s. Oedo Sukeroku Daiko was formed in Tokyo in 1959 under Seidō Kobayashi,[38] and has been referred to as the first taiko group who toured professionally.[39] Globally, kumi-daiko performance became more visible during the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, when it was featured during the Festival of Arts event.[40]

Kumi-daiko was also developed through the leadership of Den Tagayasu (田耕), who gathered young men who were willing to devote their entire lifestyle to taiko playing and took them to Sado Island for training[36][41] where Den and his family had settled in 1968.[42] Den chose the island based on a desire to reinvigorate the folk arts in Japan, particularly taiko; he became inspired by a drumming tradition unique to Sado called ondeko (鬼太鼓, "demon drumming" in the Sado dialect) that required considerable strength to play well.[43] Den called the group "Za Ondekoza" or Ondekoza for short, and implemented a rigorous set of exercises for its members including long-distance running.[35][41] In 1975, Ondekoza was the first taiko group to tour in the United States. Their first performance occurred just after the group finished running the Boston Marathon while wearing their traditional uniforms.[44][45] In 1981, some members of Ondekoza split from Den and formed another group called Kodo under the leadership of Eitetsu Hayashi.[46] Kodo continued to use Sado Island for rigorous training and communal living, and went on to popularize taiko through frequent touring and collaborations with other musical performers.[47] Kodo is one of the most recognized taiko groups both in Japan[48][49] and worldwide.[50][51]

Estimates of the number of taiko groups in Japan vary to up to 5,000 active groups in Japan,[52] but more conservative assessments place the number closer to 800 based on membership in the Nippon Taiko Foundation, the largest national organization of taiko groups.[53] Some pieces that have emerged from early kumi-daiko groups that continue to be performed include Yatai-bayashi from Ondekoza,[54] Isami-goma (勇み駒, lit. "galloping horse") from Osuwa Daiko,[55] and Zoku (族, lit. "tribe") from Kodo.[56]

Categorization

| Byō-uchi-daiko (鋲打ち太鼓) | Shime-daiko (締め太鼓) | Tsuzumi (鼓)[note 1] | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

nagadō-daiko (長胴太鼓)

|

tsukeshime-daiko (附け締め太鼓)

|

ko-tsuzumi (小鼓) | uchiwa-daiko (団扇太鼓)[58][59] |

| hira-daiko (平太鼓) | naguta shime-daiko (長唄締め太鼓) | san-no-tsuzumi (三の鼓) | den-den-daiko (でんでん太鼓) |

| tsuri-daiko (釣太鼓) | okedō-daiko (桶胴太鼓) | ō-tsuzumi (大鼓) | |

| kakko (羯鼓) | |||

| dadaiko (鼉太鼓)[note 2] | |||

Taiko have been developed into a broad range of percussion instruments that are used in both Japanese folk and classical musical traditions. An early classification system based on shape and tension was advanced by Francis Taylor Piggott in 1909.[61] Taiko are generally classified based on the construction process, or the specific context in which the drum is used,[17] but some are not classified, such as the toy den-den daiko.[62]

With few exceptions, taiko have a drum shell with heads on both sides of the body, and a sealed resonating cavity.[17] The head may be fastened to the shell using a number of different systems, such as using ropes.[17] Taiko may be either tunable or non-tunable depending on the system used.[63]

Taiko are categorized into three types based on construction process. Byō-uchi-daiko are constructed with the drumhead nailed to the body.[17] Shime-daiko are classically constructed with the skin placed over iron or steel rings, which are then tightened with ropes.[64] Contemporary shime-daiko are tensioned using bolts or turnbuckles systems attached to the drum body.[17][65] Tsuzumi are also rope-tensioned drums, but have a distinct hourglass shape and their skins are made using deerskin.[64]

Byō-uchi-daiko were historically made only using a single piece of wood;[66] they continue to be made in this manner, but are also constructed from staves of wood.[17] Larger drums can be made using a single piece of wood, but at a much greater cost due to the difficulty in finding appropriate trees.[17] The preferred wood is the Japanese zelkova or keyaki,[67] but a number of other woods, and even wine barrels, have been used to create taiko.[67][68] Byō-uchi-daiko cannot be tuned.[63]

The typical byō-uchi-daiko is the nagadō-daiko,[69] an elongated drum that is roughly shaped like a wine barrel.[70] Nagadō-daiko are available in a variety of sizes, and their head diameter is traditionally measured in shaku (units of roughly 30 cm). Head diameters range from 1 to 6 shaku (30 to 182 cm; 12 to 72 in). Ko-daiko (小太鼓) are the smallest of these drums and are usually about 1 shaku (30 cm; 12 in) in diameter.[70] The chū-daiko (中太鼓) is a medium-sized nagadō-daiko ranging from 1.6 to 2.8 shaku (48 to 85 cm; 19 to 33 in),[69] and weighing about 27 kilograms (60 lb).[70] Ō-daiko (大太鼓) vary in size, and are often as large as 6 shaku (180 cm; 72 in) in diameter.[71] Some ō-daiko are difficult to move due to their size, and therefore permanently remain inside the performance space, such as temple or shrine.[72] Ō-daiko means "large drum" and for a given ensemble, the term refers to their largest drum.[71][72] The other type of byō-uchi-daiko is called a hira-daiko (平太鼓, "flat drum") and can be any drum constructed such that the head diameter is greater than the length of the body.[73]

Shime-daiko are a set of smaller, roughly snare drum-sized instrument that are tunable.[64] The tensioning system usually consists of hemp cords or rope, but bolt or turnbuckle systems have been used as well.[65][74] Nagauta shime-daiko (長唄締め太鼓), sometimes referred to as "taiko" in the context of theater, have thinner heads than other kinds of shime-daiko.[74] The head includes a patch of deerskin placed in the center, and in performance, drum strokes are generally restricted to this area.[65] The tsukeshime-daiko (付け締め太鼓) is a heavier type of shime-daiko.[64] They are available in sizes 1–5, and are named according to their number: namitsuke (1), nichō-gakke (2), sanchō-gakke (3), yonchō-gakke (4), and gochō-gakke (5).[75] The namitsuke has the thinnest skins and the shortest body in terms of height; thickness and tension of skins, as well as body height, increase toward the gochō-gakke.[76] The head diameters of all shime-daiko sizes are around 27 cm (10.6 in).[65]

Uchiwa-daiko (団扇太鼓, literally, fan drum) is a type of racket-shaped Japanese drum. It is the only Japanese traditional drum without a sound box and only one skin. It is played with a drumstick while hanging it with the other hand.[58][59]

A middle-sized chū-daiko being played on a slanted stand

A middle-sized chū-daiko being played on a slanted stand This ō-daiko from a Kodo performance features a tomoe design on its skin.

This ō-daiko from a Kodo performance features a tomoe design on its skin. Example of a shime-daiko, tensioned using rope

Example of a shime-daiko, tensioned using rope Example of an okedō, tensioned using rope

Example of an okedō, tensioned using rope A tsuri-daiko on display at the Museu de la Música de Barcelona

A tsuri-daiko on display at the Museu de la Música de Barcelona_with_Peonies_LACMA_M.89.134.1.jpg.webp) A 17th-century ko-tsuzumi

A 17th-century ko-tsuzumi An uchiwa-daiko.

An uchiwa-daiko.

| Gagakki | Noh | Kabuki |

|---|---|---|

| dadaiko | ō-tsuzumi | ko-tsuzumi |

| tsuri-daiko | ko-tsuzumi | ō-tsuzumi |

| san-no-tsuzumi | nagauta shime-daiko | nagauta shime-daiko |

| kakko | ō-daiko | |

Okedō-daiko or simply okedō, are a type of shime-daiko that are stave-constructed using narrower strips of wood,[17][77] have a tube-shaped frame. Like other shime-daiko, drum heads are attached by metal hoops and fastened by rope or cords.[69][78] Okedō can be played using the same drumsticks (called bachi) as shime-daiko, but can also be hand-played.[78] Okedō come in short- and long-bodied types.[69]

Tsuzumi are a class of hourglass-shaped drums. The drum body is shaped on a spool and the inner body carved by hand.[79] Their skins can be made from cowhide, horsehide, or deerskin.[80] While the ō-tsuzumi skins are made from cowhide, ko-tsuzumi are made from horsehide. While some classify tsuzumi as a type of taiko,[80][64] others have described them as a drum entirely separate from taiko.[57][81]

Taiko can also be categorized by the context in which they are used. The miya-daiko, for instance, is constructed in the same manner as other byō-uchi-daiko, but is distinguished by an ornamental stand and is used for ceremonial purposes at Buddhist temples.[82][83] The Sumō-daiko (相撲太鼓) (a ko-daiko) and sairei-nagadō (祭礼長胴) (a nagadō-daiko with a cigar-shaped body) are used in sumo and festivals respectively.[84]

_A_set_of_five_prints_for_the_Hisakataya_poetry_c..._-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Several drums, categorized as gagakki, are used in the Japanese theatrical form, gagaku.[85] The lead instrument of the ensemble is the kakko,[86] which is a smaller shime-daiko with heads made of deerskin, and is placed horizontally on a stand during performance.[86] A tsuzumi, called the san-no-tsuzumi is another small drum in gagaku that is placed horizontally and struck with a thin stick.[87] Dadaiko (鼉太鼓) are the largest drums of the ensemble,[88] and have heads that are about 127 cm (50 in) in diameter. During performance, the drum is placed on a tall pedestals and surrounded by a rim decoratively painted with flames and adorned with mystical figures such as wyverns.[89] Dadaiko are played while standing,[90] and are usually only played on the downbeat of the music.[85] The tsuri-daiko (釣太鼓, "suspended drum") is a smaller drum that produces a lower sound, its head measuring about 55 cm (22 in) in diameter.[91] It is used in ensembles that accompany bugaku, a traditional dance performed at the Tokyo Imperial Palace and in religious contexts.[1] Tsuri-daiko are suspended on a small stand, and are played sitting down.[91] Tsuri-daiko performers typically use shorter mallets covered in leather knobs instead of bachi.[1] They can be played simultaneously by two performers; while one performer plays on the head, another performer uses bachi on the body of the drum.[1]

The larger ō-tsuzumi and smaller ko-tsuzumi are used in the opening and dances of Noh theater.[92] Both drums are struck using the fingers; players can also adjust pitch by manually applying pressure to the ropes on the drum.[93] The color of the cords of these drums also indicates the skill of the musician: Orange and red for amateur players, light blue for performers with expertise, and lilac for masters of the instrument.[94] Nagauta-shime daiko or uta daiko are also featured in Noh performance.[95][96]

Many taiko in Noh are also featured in kabuki performance and are used in a similar manner.[97] In addition to the ō-tsuzumi, ko-tsuzumi, and nagauta-shime daiko,[98] Kabuki performances make use of the larger ō-daiko offstage to help set the atmosphere for different scenes.[99]

Construction

Process

Taiko construction has several stages, including making and shaping of the drum body (or shell), preparing the drum skin, and tuning the skin to the drumhead. Variations in the construction process often occur in the latter two parts of this process.[100] Historically, byō-uchi-daiko were crafted from trunks of the Japanese zelkova tree that were dried out over years, using techniques to prevent splitting. A master carpenter then carved out the rough shape of the drum body with a chisel; the texture of the wood after carving softened the tone of the drum.[100][101] In contemporary times, taiko are carved out on a large lathe using wood staves[66] or logs that can be shaped to fit drum bodies of various sizes.[102] Drumheads can be left to air-dry over a period of years,[103] but some companies use large, smoke-filled warehouses to hasten the drying process.[101] After drying is complete, the inside of the drum is worked with a deep-grooved chisel and sanded.[103] Lastly, handles are placed onto the drum. These are used to carry smaller drums and they serve an ornamental purpose for larger drums.[104]

The skins or heads of taiko are generally made from cowhide from Holstein cows aged about three or four years. Skins also come from horses, and bull skin is preferred for larger drums.[21][100] Thinner skins are preferred for smaller taiko, and thicker skins are used for larger ones.[105] On some drumheads, a patch of deer skin placed in the center serves as the target for many strokes during performance.[21] Before fitting it to the drum body the hair is removed from the hide by soaking it in a river or stream for about a month; winter months are preferred as colder temperatures better facilitate hair removal.[104] To stretch the skin over the drum properly, one process requires the body to be held on a platform with several hydraulic jacks underneath it. The edges of the cowhide are secured to an apparatus below the jacks, and the jacks stretch the skin incrementally to precisely apply tension across the drumhead.[106] Other forms of stretching use rope or cords with wooden dowels or an iron wheel to create appropriate tension.[104][107] Small tension adjustments can be made during this process using small pieces of bamboo that twist around the ropes.[104] Particularly large drumheads are sometimes stretched by having several workers, clad in stockings, hop rhythmically atop it, forming a circle along the edge. After the skin has dried, tacks, called byō, are added to the appropriate drums to secure it; chū-daiko require about 300 of them for each side.[108] After the body and skin have been finished, excess hide is cut off and the drum can be stained as needed.[108]

Drum makers

Several companies specialize in the production of taiko. One such company that created drums exclusively for the Emperor of Japan, Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten in Tokyo, has been making taiko since 1861.[100] The Asano Taiko Corporation is another major taiko-producing organization, and has been producing taiko for over 400 years.[109][110] The family-owned business started in Mattō, Ishikawa, and, aside from military equipment, made taiko for Noh theater and later expanded to creating instruments for festivals during the Meiji period. Asano currently maintains an entire complex of large buildings referred to as Asano Taiko Village,[109] and the company reports producing up to 8000 drums each year.[111] As of 2012, there is approximately one major taiko production company in each prefecture of Japan, with some regions having several companies.[112] Of the manufacturers in Naniwa, Taikoya Matabē is one of the most successful and is thought to have brought considerable recognition to the community and attracted many drum makers there.[113] Umetsu Daiko, a company that operates in Hakata, has been producing taiko since 1821.[103]

Performance

Taiko performance styles vary widely across groups in terms of the number of performers, repertoire, instrument choices, and stage techniques.[114] Nevertheless, a number of early groups have had broad influence on the tradition. For instance, many pieces developed by Ondekoza and Kodo are considered standard in many taiko groups.[115]

Form

Kata is the posture and movement associated with taiko performance.[31][116] The notion is similar to that of kata in martial arts: for example, both traditions include the idea that the hara is the center of being.[31][117] Author Shawn Bender argues that kata is the primary feature that distinguishes different taiko groups from one another and is a key factor in judging the quality of performance.[118] For this reason, many practice rooms intended for taiko contain mirrors to provide visual feedback to players.[119] An important part of kata in taiko is keeping the body stabilized while performing and can be accomplished by keeping a wide, low stance with the legs, with the left knee bent over the toes and keeping the right leg straight.[31][120] It is important that the hips face the drum and the shoulders are relaxed.[120] Some teachers note a tendency to rely on the upper body while playing and emphasize the importance of the holistic use of the body during performance.[121]

Some groups in Japan, particularly those active in Tokyo, also emphasize the importance of the lively and spirited iki aesthetic.[122] In taiko, it refers to very specific kinds of movement while performing that evoke the sophistication stemming from the mercantile and artisan classes active during the Edo period (1603–1868).[122]

The sticks for playing taiko are called bachi, and are made in various sizes and from different kinds of wood such as white oak, bamboo, and Japanese magnolia.[123] Bachi are also held in a number of different styles.[124] In kumi-daiko, it is common for a player to hold their sticks in a relaxed manner between the V-shape of the index finger and thumb, which points to the player.[124] There are other grips that allow performers to play much more technically difficult rhythms, such as the shime grip, which is similar to a matched grip: the bachi are gripped at the back end, and the fulcrum rests between the performer's index finger and thumb, while the other fingers remain relaxed and slightly curled around the stick.[125]

Performance in some groups is also guided by principles based on Zen Buddhism. For instance, among other concepts, the San Francisco Taiko Dojo is guided by rei (礼) emphasizing communication, respect, and harmony.[126] The way the bachi are held can also be significant; for some groups, bachi represent a spiritual link between the body and the sky.[127] Some physical parts of taiko, like the drum body, its skin, and the tacks also hold symbolic significance in Buddhism.[127]

Instrumentation

Kumi-daiko groups consist primarily of percussive instruments where each of the drums plays a specific role. Of the different kinds of taiko, the most common in groups is the nagadō-daiko.[128] Chū-daiko are common in taiko groups[31] and represent the main rhythm of the group, whereas shime-daiko set and change tempo.[70] A shime-daiko often plays the Jiuchi, a base rhythm holding together the ensemble. Ō-daiko provide a steady, underlying pulse[34] and serve as a counter-rhythm to the other parts.[129] It is common for performances to begin with a single stroke roll called an oroshi (颪, "wind blowing down from mountains").[130] The player starts slowly, leaving considerable space between strikes, gradually shortening the interval between hits, until the drummer is playing a rapid roll of hits.[130] Oroshi are also played as a part of theatrical performance, such as in Noh theater.[21]

Drums are not the only instruments played in the ensemble; other Japanese instruments are also used. Other kinds of percussion instruments include the atarigane (当り鉦), a hand-sized gong played with a small mallet.[131] In kabuki, the shamisen, a plucked string instrument, often accompanies taiko during the theatrical performance.[132] Kumi-daiko performances can also feature woodwinds such as the shakuhachi[133] and the shinobue.[134][135]

Voiced calls or shouts called kakegoe and kiai are also common in taiko performance.[136][137] They are used as encouragement to other players or cues for transition or change in dynamics such as an increase in tempo.[138] In contrast, the philosophical concept of ma, or the space between drum strikes, is also important in shaping rhythmic phrases and creating appropriate contrast.[139]

Clothing

There is a wide variety of traditional clothing that players wear during taiko performance. Common in many kumi-daiko groups is the use of the happi, a decorative, thin-fabric coat, and traditional headbands called hachimaki.[140] Tabi, momohiki (もも引き, "loose-fitting pants"), and haragake (腹掛け, "working aprons") are also typical.[141] During his time with the group Ondekoza, Eitetsu Hayashi suggested that a loincloth called a fundoshi be worn when performing for French fashion designer Pierre Cardin, who saw Ondekoza perform for him in 1975.[142] The Japanese group Kodo has sometimes worn fundoshi for its performances.[143]

Education

Taiko performance is generally taught orally and through demonstration.[144][145] Historically, general patterns for taiko were written down, such as in the 1512 encyclopedia called the Taigensho,[146] but written scores for taiko pieces are generally unavailable. One reason for the adherence to an oral tradition is that, from group to group, the rhythmic patterns in a given piece are often performed differently.[147] Furthermore, ethnomusicologist William P. Malm observed that Japanese players within a group could not usefully predict one another using written notation, and instead did so through listening.[148] In Japan, printed parts are not used during lessons.[146]

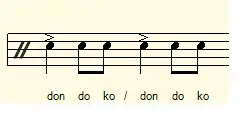

Orally, patterns of onomatopoeia called kuchi shōga are taught from teacher to student that convey the rhythm and timbre of drum strikes for a particular piece.[149][150] For example, don (どん) represents a single strike to the center of the drum,[150] where as do-ko (どこ) represents two successive strikes, first by the right and then the left, and lasts the same amount of time as one don strike.[151] Some taiko pieces, such as Yatai-bayashi, include patterns that are difficult to represent in Western musical notation.[151] The exact words used can also differ from region to region.[151]

More recently, Japanese publications have emerged in an attempt to standardize taiko performance. The Nippon Taiko Foundation was formed in 1979; its primary goals were to foster good relations among taiko groups in Japan and to both publicize and teach how to perform taiko.[152][153] Daihachi Oguchi, the leader of the Foundation, wrote Japan Taiko with other teachers in 1994 out of concern that correct form in performance would degrade over time.[154] The instructional publication described the different drums used in kumi-daiko performance, methods of gripping, correct form, and suggestions on instrumentation. The book also contains practice exercises and transcribed pieces from Oguchi's group, Osuwa Daiko. While there were similar textbooks published before 1994, this publication had much more visibility due to the Foundation's scope.[155]

The system of fundamentals Japan Taiko put forward was not widely adopted because taiko performance varied substantially across Japan. An updated 2001 publication from the Foundation, called the Nihon Taiko Kyōhon (日本太鼓教本, "Japan Taiko Textbook"), describes regional variations that depart from the main techniques taught in the textbook. The creators of the text maintained that mastering a set of prescribed basics should be compatible with learning local traditions.[156]

Regional styles

Aside from kumi-daiko performance, a number of folk traditions that use taiko have been recognized in different regions in Japan. Some of these include ondeko (鬼太鼓, "demon drumming") from Sado Island, gion-daiko from the town of Kokura, and sansa-odori from Iwate Prefecture.[157]

Eisa

A variety of folk dances originating from Okinawa, known collectively as eisa, often make use of the taiko.[158] Some performers use drums while dancing, and generally speaking, perform in one of two styles:[159] groups on the Yokatsu Peninsula and on Hamahiga Island use small, single-sided drums called pāranku (パーランク) whereas groups near the city of Okinawa generally use shime-daiko.[158][160] Use of shime-daiko over pāranku has spread throughout the island, and is considered the dominant style.[160] Small nagadō-daiko, referred to as ō-daiko within the tradition, are also used[161] and are worn in front of the performer.[162] These drum dances are not limited to Okinawa and have appeared in places containing Okinawan communities such as in São Paulo, Hawaii, and large cities on the Japanese mainland.[163]

Hachijō-daiko

Hachijō-daiko (八丈太鼓, trans. "Hachijō-style taiko") is a taiko tradition originating on the island of Hachijō-jima.[164] Two styles of Hachijō-daiko emerged and have been popularized among residents: an older tradition based on a historical account, and a newer tradition influenced by mainland groups and practiced by the majority of the islanders.[164]

The Hachijō-daiko tradition was documented as early as 1849 based on a journal kept by an exile named Kakuso Kizan. He mentioned some of its unique features, such as "a taiko is suspended from a tree while women and children gathered around", and observed that a player used either side of the drum while performing.[165] Illustrations from Kizan's journal show features of Hachijō-daiko. These illustrations also featured women performing, which is unusual as taiko performance elsewhere during this period was typically reserved for men. Teachers of the tradition have noted that the majority of its performers were women; one estimate asserts that female performers outnumbered males by three to one.[166]

The first style of Hachijō-daiko is thought to descend directly from the style reported by Kizan. This style is called Kumaoji-daiko, named after its creator Okuyama Kumaoji, a central performer of the style.[167] Kumaoji-daiko has two players on a single drum, one of whom, called the shita-byōshi (下拍子, "lower beat"), provides the underlying beat.[168] The other player, called the uwa-byōshi (上拍子, "upper beat"), builds on this rhythmical foundation with unique and typically improvised rhythms.[168][169] While there are specific types of underlying rhythms, the accompanying player is free to express an original musical beat.[168] Kumaoji-daiko also features an unusual positioning for taiko: the drums are sometimes suspended from ropes,[170] and historically, sometimes drums were suspended from trees.[165]

The contemporary style of Hachijō-daiko is called shin-daiko (新太鼓, "new taiko"), which differs from Kumaoji-daiko in multiple ways. For instance, while the lead and accompanying roles are still present, shin-daiko performances use larger drums exclusively on stands.[171] Shin-daiko emphasizes a more powerful sound, and consequently, performers use larger bachi made out of stronger wood.[172] Looser clothing is worn by shin-daiko performers compared to kimono worn by Kumaoji-daiko performers; the looser clothing in shin-daiko allow performers to adopt more open stances and larger movements with the legs and arms.[173] Rhythms used for the accompanying shita-byōshi role can also differ. One type of rhythm, called yūkichi, consists of the following:

This rhythm is found in both styles, but is always played faster in shin-daiko.[174] Another type of rhythm, called honbadaki, is unique to shin-daiko and also contains a song which is performed in standard Japanese.[174]

Miyake-daiko

Miyake-daiko (三宅太鼓, trans. "Miyake-style taiko") is a style that has spread amongst groups through Kodo, and is formally known as Miyake-jima Kamitsuki mikoshi-daiko (三宅島神着神輿太鼓).[175] The word miyake comes from Miyake-jima, part of the Izu Islands, and the word Kamitsuki refers to the village where the tradition came from. Miyake-style taiko came out of performances for Gozu Tennō Sai (牛頭天王祭, "Gozu Tennō Festival")— a traditional festival held annually in July on Miyake Island since 1820 honoring the deity Gozu Tennō.[176] In this festival, players perform on taiko while portable shrines are carried around town.[177] The style itself is characterized in a number of ways. A nagadō-daiko is typically set low to the ground and played by two performers, one on each side; instead of sitting, performers stand and hold a stance that is also very low to the ground, almost to the point of kneeling.[177][178]

Outside Japan

Australia

Taiko groups in Australia began forming in the 1990s.[179] The first group, called Ataru Taru Taiko, was formed in 1995 by Paulene Thomas, Harold Gent, and Kaomori Kamei.[180] TaikOz was later formed by percussionist Ian Cleworth and Riley Lee, a former Ondekoza member, and has been performing in Australia since 1997.[181] They are known for their work in generating interest in performing taiko among Australian audiences, such as by developing a complete education program with both formal and informal classes,[182] and have a strong fan base.[183] Cleworth and other members of the group have developed several original pieces.[184]

Brazil

The introduction of kumi-daiko performance in Brazil can be traced back to the 1970s and 1980s in São Paulo.[185] Tangue Setsuko founded an eponymous taiko dojo and was Brazil's first taiko group;[185] Setsuo Kinoshita later formed the group Wadaiko Sho.[186] Brazilian groups have combined native and African drumming techniques with taiko performance. One such piece developed by Kinoshita is called Taiko de Samba, which emphasizes both Brazilian and Japanese aesthetics in percussion traditions.[187] Taiko was also popularized in Brazil from 2002 through the work of Yukihisa Oda, a Japanese native who visited Brazil several times through the Japan International Cooperation Agency.[188]

The Brazilian Association of Taiko (ABT) suggests that there are about 150 taiko groups in Brazil and that about 10–15% of players are non-Japanese; Izumo Honda, coordinator of a large annual festival in São Paulo, estimated that about 60% of all taiko performers in Brazil are women.[188]

North America

Taiko emerged in the United States in the late 1960s. The first group, San Francisco Taiko Dojo, was formed in 1968 by Seiichi Tanaka, a postwar immigrant who studied taiko in Japan and brought the styles and teachings to the US.[189][190] A year later, a few members of Senshin Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles led by its minister Masao Kodani initiated another group called Kinnara Taiko.[191] San Jose Taiko later formed in 1973 in Japantown, San Jose, under Roy and PJ Hirabayashi.[192][193] Taiko started to branch out to the eastern US in the late 1970s.[194] This included formation of Denver Taiko in 1976,[194] and Soh Daiko in New York City in 1979.[195][196] Many of these early groups lacked the resources to equip each member with a drum and resorted to makeshift percussion materials such as rubber tires or creating taiko out of wine barrels.[194]

Japanese-Canadian taiko began in 1979 with Katari Taiko, and was inspired by the San Jose Taiko group.[197][198] Its early membership was predominantly female.[199] Katari Taiko and future groups were thought to represent an opportunity for younger, third-generation Japanese Canadians to explore their roots, redevelop a sense of ethnic community, and expand taiko into other musical traditions.[200]

There are no official counts or estimates of the number of active taiko groups in the United States or Canada, as there is no governing body for taiko groups in either country. Unofficial estimates have been made. In 1989, there were as many as 30 groups in the US and Canada, seven of which were in California.[201] One estimate suggested that around 120 groups were active in the US and Canada as of 2001, many of which could be traced to the San Francisco Taiko Dojo;[68] later estimates in 2005 and 2006 suggested there were about 200 groups in the United States alone.[52][193]

The Cirque du Soleil shows Mystère in Las Vegas[202] and Dralion have featured taiko performance.[203][204] Taiko performance has also been featured in commercial productions such as the 2005 Mitsubishi Eclipse ad campaign,[205] and in events such as the 2009 Academy Awards and 2011 Grammy Awards.[206]

From 2005 to 2006, the Japanese American National Museum held an exhibition called Big Drum: Taiko in the United States.[207] The exhibition covered several topics related to taiko in the United States, such as the formation of performance groups, their construction using available materials, and social movements. Visitors were able to play smaller drums.[208]

Italy

The first group, called Quelli del Taiko, was formed in 2000 by Pietro Notarnicola. They played in World Premiere - 2017 - "On Western Terror 8" - Concerto for Taiko Ensemble and Orchestra of the Italian composed Luigi Morleo

Related cultural and social movements

Certain peoples have used taiko to advance social or cultural movements, both within Japan and elsewhere in the world.

Gender conventions

Taiko performance has frequently been viewed as an art form dominated by men.[209][210] Historians of taiko argue that its performance comes from masculine traditions. Those who developed ensemble-style taiko in Japan were men,[210] and through the influence of Ondekoza, the ideal taiko player was epitomized in images of the masculine peasant class,[210] particularly through the character Muhōmatsu in the 1958 film Rickshaw Man.[140][210] Masculine roots have also been attributed to perceived capacity for "spectacular bodily performance" [211] where women's bodies are sometimes judged as unable to meet the physical demands of playing.[212]

Before the 1980s, it was uncommon for Japanese women to perform on traditional instruments, including taiko, as their participation had been systematically restricted; an exception was the San Francisco Taiko Dojo under the guidance of Grand master Seiichi Tanaka, who was the first to admit females to the art form.[210] In Ondekoza and in the early performances of Kodo, women performed only dance routines either during or between taiko performances.[213] Thereafter, female participation in kumi-daiko started to rise dramatically, and by the 1990s, women equaled and possibly exceeded representation by men.[210] While the proportion of women in taiko has become substantial, some have expressed concern that women still do not perform in the same roles as their male counterparts and that taiko performance continues to be a male-dominated profession.[212] For instance, a member of Kodo was informed by the director of the group's apprentice program that women were permitted to play, but could only play "as women".[214] Other women in the apprentice program recognized a gender disparity in performance roles, such as what pieces they were allowed to perform, or in physical terms based on a male standard.[215]

Female taiko performance has also served as a response to gendered stereotypes of Japanese women as being quiet,[200] subservient, or a femme fatale.[216] Through performance, some groups believe they are helping to redefine not only the role of women in taiko, but how women are perceived more generally.[216][217]

Burakumin

Those involved in the construction of taiko are usually considered part of the burakumin, a marginalized minority class in Japanese society, particularly those working with leather or animal skins.[105] Prejudice against this class dates back to the Tokugawa period in terms of legal discrimination and treatment as social outcasts.[218] Although official discrimination ended with the Tokugawa era, the burakumin have continued to face social discrimination, such as scrutiny by employers or in marriage arrangements.[219] Drum makers have used their trade and success as a means to advocate for an end to discriminatory practices against their class.[218]

The Taiko Road (人権太鼓ロード, "Taiko Road of Human Rights"), representing the contributions of burakumin, is found in Naniwa Ward in Osaka, home to a large proportion of burakumin.[112] Among other features, the road contains taiko-shaped benches representing their traditions in taiko manufacturing and leatherworking, and their influence on national culture.[113][219] The road ends at the Osaka Human Rights Museum, which exhibits the history of systematic discrimination against the burakumin.[219] The road and museum were developed in part due an advocacy campaign led by the Buraku Liberation League and a taiko group of younger performers called Taiko Ikari (太鼓怒り, "taiko rage").[112]

North American sansei

Taiko performance was an important part of cultural development by third-generation Japanese residents in North America, who are called sansei.[193][220] During World War II, second-generation Japanese residents, called nisei faced internment in the United States and in Canada on the basis of their race.[221][222] During and after the war, Japanese residents were discouraged from activities such as speaking Japanese or forming ethnic communities.[222] Subsequently, sansei could not engage in Japanese culture and instead were raised to assimilate into more normative activities.[223] There were also prevailing stereotypes of Japanese people, which sansei sought to escape or subvert.[223] During the 1960s in the United States, the civil rights movement influenced sansei to reexamine their heritage by engaging in Japanese culture in their communities; one such approach was through taiko performance.[222][223] Groups such as San Jose Taiko were organized to fulfill a need for solidarity and to have a medium to express their experiences as Japanese-Americans.[224] Later generations have adopted taiko in programs or workshops established by sansei; social scientist Hideyo Konagaya remarks that this attraction to taiko among other Japanese art forms may be due to its accessibility and energetic nature.[225] Konagaya has also argued that the resurgence of taiko in the United States and Japan are differently motivated: in Japan, performance was meant to represent the need to recapture sacred traditions, while in the United States it was meant to be an explicit representation of masculinity and power in Japanese-American men.[226]

Notable performers and groups

A number of performers and groups, including several early leaders, have been recognized for their contributions to taiko performance. Daihachi Oguchi was best known for developing kumi-daiko performance. Oguchi founded the first kumi-daiko group called Osuwa Daiko in 1951, and facilitated the popularization of taiko performance groups in Japan.[227]

Seidō Kobayashi is the leader of the Tokyo-based taiko group Oedo Sukeroku Taiko as of December 2014.[228][229] Kobayashi founded the group in 1959 and was the first group to tour professionally.[228] Kobayashi is considered a master performer of taiko.[230] He is also known for asserting intellectual control of the group's performance style, which has influenced performance for many groups, particularly in North America.[231]

In 1968, Seiichi Tanaka founded the San Francisco Taiko Dojo and is regarded as the Grandfather of Taiko and primary developer of taiko performance in the United States.[232][233] He was a recipient of a 2001 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts[189] and since 2013 is the only taiko professional presented with the Order of the Rising Sun 5th Order: Gold and Silver Rays by Emperor Akihito of Japan, in recognition of Grandmaster Seiichi Tanaka's contributions to the fostering of US-Japan relations as well as the promotion of Japanese cultural understanding in the United States.[234]

In 1969, Den Tagayasu (田耕, Den Tagayasu) founded Ondekoza, a group well known for making taiko performance internationally visible and for its artistic contributions to the tradition.[115] Den was also known for developing a communal living and training facility for Ondekoza on Sado Island in Japan, which had a reputation for its intensity and broad education programs in folklore and music.[235]

Performers and groups beyond the early practitioners have also been noted. Eitetsu Hayashi is best known for his solo performance work.[236] When he was 19, Hayashi joined Ondekoza, a group later expanded and re-founded as Kodo, one of the best known and most influential taiko performance groups in the world.[237] Hayashi soon left the group to begin a solo career[236] and has performed in venues such as Carnegie Hall in 1984, the first featured taiko performer there.[46][238] He was awarded the 47th Education Minister's Art Encouragement Prize, a national award, in 1997 as well as the 8th Award for the Promotion of Traditional Japanese Culture from the Japan Arts Foundation in 2001.[239]

Glossary

| Romanized Japanese | IPA Pronunciation | Kanji | Definition[240] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachi | [batɕi] | 撥 | Various drumsticks used for taiko performance |

| Byō-uchi-daiko | [bʲoːɯtɕidaiko] | 鋲打ち太鼓 | Taiko where the skin is tacked onto the head |

| Gagakki | [ɡaɡakki] | 雅楽器 | Instruments used in the theatrical tradition called gagaku |

| Kumi-daiko | [kɯmidaiko] | 組太鼓 | Type of performance involving multiple players and different types of taiko |

| Nagadō-daiko | [naɡadoːdaiko] | 長胴太鼓 | Subcategory of byō-uchi-daiko that have a longer, barrel-shaped body |

| Miya-daiko | [mijadaiko] | 宮太鼓 | Same as Nagado but only for sacred use at temples |

| Okedō-daiko | [okedoːdaiko] | 桶胴太鼓 | Taiko with bucket-like frames, and tensioned using ropes or bolts |

| Shime-daiko | [ɕimedaiko] | 締め太鼓 | Small, high-pitched taiko where the skin is pulled across the head using rope or through bolts |

| Tsuzumi | [tsɯzɯmi] | 鼓 | Hourglass-shaped drums that are rope-tensioned and played with fingers |

See also

- Kuchi shōga, a spoken rhythmic system for taiko and other Japanese instruments.

- Music of Japan

- Taiko: Drum Master and Taiko no Tatsujin, rhythm video games involving taiko performance.

References

Notes

Citations

- Blades 1992, pp. 122–123.

- Nelson 2007, pp. 36, 39.

- Schuller 1989, p. 202.

- Cossío 2001, p. 179.

- Bender 2012, p. 26.

- Harich-Schneider 1973, pp. 108, 110.

- "Music Festival at the Museum". Tokyo National Museum. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Dean 2012, p. 122.

- Dean 2012, p. 122; Varian 2013, p. 21.

- Ochi, Megumi. "What The Haniwa Have to Say About Taiko's Roots: The History of Taiko". Rolling Thunder. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Varian 2013, p. 21.

- Minor 2003, pp. 37–39; Izumi 2001, pp. 37–39; Raz 1983, p. 19.

- Turnbull 2008, p. 37.

- Turnbull 2012, pp. 27–28.

- Turnbull 2012, p. 27.

- Turnbull 2008, p. 49.

- Gould 1998, p. 12.

- Brandon & Leiter 2002, p. 86.

- Miki 2008, p. 176.

- Malm 2000, pp. 286–288.

- Malm 1960, pp. 75–78.

- Malm 2000, pp. 101–102.

- Malm 2000, pp. 103.

- "Kenny Endo: Connecting to Heritage through Music". Big Drum. Japanese American National Museum. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Miki 2008, p. 180.

- Bender 2012, p. 110.

- Malm 2000, p. 77.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 134.

- Ingram 2004, p. 71.

- Miller & Shahriari 2014, p. 146.

- Powell 2012a.

- Varian 2005, p. 33.

- "Daihachi Oguchi, 84, Japanese Drummer, Dies". The New York Times. Associated Press. 28 June 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Alves 2012, p. 312.

- Varian 2005, p. 28.

- Varian 2005, p. 29.

- Bender 2012, p. 51.

- Powell 2012b, p. 125.

- Wong 2004, p. 204.

- Varian 2005, pp. 28–29.

- Wald & Vartoogian 2007, p. 251.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 65.

- Konagaya 2005, pp. 64–65.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 149.

- McLeod 2013, p. 171.

- Hoover 2011, p. 98.

- Lacashire 2011, p. 14.

- Arita, Eriko (17 August 2012). "Kodo drum troupe marks 25 years of Earth Celebration". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Matsumoto, John (17 August 1990). "Gospel and Drums According to Kodo : Music: Southland choir members will blend their talents with rhythms of Japanese ensemble in non-traditional concert on Sado Island in Japan". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Bender 2012, p. 72.

-

- Barr, Gordon (19 February 2014). "Japanese taiko drumming troupe Kodo head to Sage Gateshead". Chronicle Live. Trinity Mirror North East. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Keogh, Tom (30 January 2009). "Top taiko drum group, Kodo, rolls into town". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Soh Daiko, the Fine Art of Japanese Drumming". The New York Times. 2 May 1986. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Varian 2005, p. 17.

- Bender 2012, p. 3.

- Bender 2012, p. 74.

- Bender 2012, p. 87.

- Bender 2012, p. 102.

- Blades 1992, p. 124.

- 【身延山開闢会・入山行列2009】by<SAL> その1 (in Japanese), archived from the original on 2021-11-14, retrieved 2019-12-14

- だんだん近づく法華の太鼓 身延 七面山 日蓮宗の信仰登山風景 (in Japanese), archived from the original on 2021-11-14, retrieved 2019-12-14

- 30秒の心象風景8350・大きな彫刻装飾~鼉太鼓~ (in Japanese), archived from the original on 2021-11-14, retrieved 2019-12-14

- Piggott 1971, pp. 191–203.

- Kakehi, Tamori & Schourup 1996, p. 251.

- Tusler 2003, p. 60.

- Varian 2013, p. 57.

- Miki 2008, p. 177.

- Carlsen 2009, pp. 130–131.

- Ammer 2004, p. 420.

- Liu, Terry (2001). "Go For Broke". 2001 NEA National Heritage Scholarships. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Drums and Other Instruments". The Shumei Taiko Ensemble. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Varian 2013, p. 55.

- Titon & Fujie 2005, p. 184.

- "Heartbeat of Drums". Classical TV. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Varian 2013, pp. 121–122.

- Varian 2013, p. 130.

- Varian 2013, pp. 119, 126.

- Varian 2013, p. 119.

- "Taiko in the United States". Japanese American National Museum. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Miki 2008, p. 181.

- Blades 1992, p. 126.

- Bender 2012, p. 28.

- Miki 2008, p. 156.

- Gould 1998, p. 13.

- Yoon 2001, p. 420.

- Varian 2013, pp. 129, 131.

- Miki 2008, p. 169.

- Malm 2000, p. 104.

- Bender 2012, p. 27.

- Malm 2000, p. 335.

- Blades 1992, pp. 124–125.

- Blades 1992, pp. 123.

- Miki 2008, p. 171.

- Malm 2000, pp. 137, 142.

- Varian 2013, p. 58.

- Blades 1992, p. 127.

- Blades 1992, p. 125.

- Roth 2002, p. 161.

- Malm 1963, pp. 74–77.

- Malm 1963, pp. 75.

- Brandon & Leiter 2002, pp. 153, 363.

- Varian 2013, p. 53.

- Bender 2012, p. 35.

- Varian 2013, p. 54.

- Gould 1998, p. 17.

- Gould 1998, p. 18.

- Bender 2012, p. 36.

- Carlsen 2009, p. 131.

- Cangia 2013, p. 36.

- Gould 1998, p. 19.

- Bender 2012, pp. 34–35.

- Dretzka, Gary; Caro, Mark (1 March 1998). "How 'An Alan Smithee Film' Became An Alan Smithee Film". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- 株式会社浅野太鼓楽器店. Asano.jp (in Japanese). Asano Taiko Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Bender 2012, p. 38.

- Bender 2012, p. 44.

- Bender 2012, pp. 19, 70.

- Bender 2012, p. 60.

- Tusler 2003, pp. 73–74.

- Varian 2013, p. 89.

- Bender 2012, p. 10.

- Bender 2012, p. 122.

- Varian 2013, p. 94.

- Bender 2005, p. 201.

- Bender 2005, p. 58.

- Varian 2013, p. 59.

- Varian 2013, p. 92.

- "N/A". Modern Percussionist. Modern Drummer Publications, Inc. 3: 28. 1986. OCLC 11672313.

- Wong 2004, p. 84.

- Powell 2012b, Ki.

- Dean 2012, p. 125.

- Tusler 2003, pp. 70, 72.

- Powell 2012a, chpt. 7.

- Bender 2012, p. 32.

- Bender 2012, p. 29.

- Nelson 2007, p. 287.

- Nelson 2007, p. 288.

- Forss 2010, p. 597.

- Nelson 2007, p. 139.

- Varian 2013, p. 62.

- Bender 2012, pp. 29, 51.

- Varian 2013, pp. 89–90, 125.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 150.

- Konagaya 2010, p. 645.

- "N/A". Asian Music. Society for Asian Music. 40: 108. 2009. OCLC 53164383.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 151.

- Bender 2012, p. 115.

- Malm 1986, p. 24.

- Harich-Schneider 1973, p. 394.

- Malm 1986, p. 202.

- Malm 1986, pp. 24–25.

- Tusler 2003, pp. 90, 271.

- Varian 2013, p. 90.

- Bender 2012, p. 139.

- Bender 2012, p. 182.

- Cangia 2013, p. 129.

- Bender 2012, p. 183.

- Bender 2012, p. 184.

- Bender 2012, pp. 185–187.

- Bender 2012, p. 225.

- Terada 2013, p. 234.

- Kumada 2011, pp. 193–244.

- Kobayashi 1998, pp. 36–40.

- Cangia 2013, p. 149.

- Bender 2012, p. 210.

- Terada 2013, p. 235.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 171.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 2.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 3.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 5.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 8.

- Honda 1984, p. 931.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 7.

- Alaszewska 2008, pp. 14, 18–19.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 19.

- Alaszewska 2008, pp. 14, 19.

- Alaszewska 2008, p. 14.

- Bender 2012, p. 98.

- Ikeda 1983, p. 275.

- "Overview". Miyake Taiko. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Bender 2012, pp. 98–99.

- Bloustein 1999, p. 131.

- Bloustein 1999, p. 166.

- de Ferranti 2007, p. 80.

- Webb & Seddon 2012, p. 762.

- de Ferranti 2007, p. 91.

- de Ferranti 2007, p. 84.

- Lorenz 2007, p. 102.

- Lorenz 2007, p. 26.

- Lorenz 2007, pp. 115, 130–139.

- Horikawa, Helder. "Matérias Especiais – Jornal NippoBrasil" (in Portuguese). Nippobrasil. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Seiichi Tanaka". 2001 NEA National Heritage Fellowships. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Konagaya 2005, pp. 136–138.

- Konagaya 2005, pp. 136, 144.

- "Roy and PJ Hirabayashi". 2011 NEA National Heritage Fellowships. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Izumi 2006, p. 159.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 145.

- Douglas, Martin (22 October 1995). "New Yorkers & Co.; Banging the Drum Not So Slowly". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Gottfried, Erika. "Guide to the Soh Daiko Archive Records and Videotapes". The Taminant Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "History". Vancouver Taiko Society. 5 October 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Nomura 2005, p. 333.

- Li 2011, p. 55.

- Izumi 2001, pp. 37–39.

- Tagashira, Gail (3 February 1989). "Local Groups Share Taiko Drum Heritage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Przybys, John (31 March 2014). "Ex-acrobat tells of soaring with Cirque du Soleil, helping others reach dreams". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Stephens Media. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- Rainey, Sarah (27 May 2014). "Cirque du Soleil: a day learning tricks at the circus". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- Keene 2011, pp. 18–19.

- "Full Company History". TAIKOPROJECT. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Taiko Project to Showcase Fresh Interpretation of Drumming". Skidmore College. 8 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Big Drum: Taiko in the United States". Japanese American National Museum. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Izumi 2006, pp. 158–159.

-

- "Hono Taiko". The New Yorker. F-R Publishing Corporation. 11 October 1999. p. 17.

- Lin, Angel (20 April 2007). "Taiko Drummers Celebrate Heritage". The Oberlin Review. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Bender 2012, p. 144.

- Konagaya 2007, p. 2.

- Bender 2012, p. 145.

- Bender 2012, p. 155.

- Bender 2012, p. 153.

- Bender 2012, pp. 154–155.

- Chan, Erin (15 July 2002). "They're Beating the Drum for Female Empowerment". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Wong 2000, p. 74.

- Bender 2012, p. 37.

- Priestly, Ian (20 January 2009). "Breaking the silence on burakumin". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Yoon 2001, p. 422.

- Terada 2001, pp. 40–41.

- Izumi 2001, p. 41.

- Terada 2001, p. 41.

- Yoon 2001, p. 424.

- Konagaya 2001, p. 117.

- Konagaya 2005, p. 140.

- Bender 2012, p. 52.

- Bender 2012, p. 59.

- "Performing Members". Oedo Sukeroku Taiko. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Electronic Musician. Polyphony Publishing Company. 11 (7–12): 52. 1995. OCLC 181819338.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Wong 2004, p. 85.

- Varian 2013, p. 31.

- Tusler 2003, p. 127.

- "Awards and Accolades". San Francisco Taiko Dojo. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Bender 2012, pp. 68–70.

- "Eitetsu Hayashi – Japan's Premier Taiko Drummer". Katara. Katara Art Studios. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Rosen, D. H. (2006). "Creating Tradition, One Beat at a Time". Japan Spotlight: Economy, Culture & History. Japan Economic Foundation: 52. OCLC 54028278.

- Thornbury 2013, p. 137.

- "Eitetsu Hayashi Biographies". San Francisco International Arts Festival. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Varian 2013, pp. 118–134.

Bibliography

- Alaszewska, Jane (2008). Mills, Simon (ed.). Analysing East Asian Music: Patterns of Rhythm and Melody. Semar Publishers SRL. ISBN 978-8877781048.

- Alves, William (2012). Music of the Peoples of the World (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1133712305.

- Ammer, Christine (2004). The Facts on File: Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Facts on File. ISBN 1438130090.

- Cossío, Óscar Cossío (2001). La Tensión Espiritual del Teatro Nô (in Spanish). Dirección de Literatura, UNAM. ISBN 9683690874.

- Bender, Shawn (2005). "Of Roots and Race: Discourses of Body and Place in Japanese Taiko Drumming". Social Science Japan. 8 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyi038.

- Bender, Shawn (2012). Taiko Boom: Japanese Drumming in Place and Motion. Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0520951433.

- Blades, James (1992). Percussion Instruments and Their History (Revised ed.). Bold Strummer. ISBN 0933224613.

- Bloustein, Gerry, ed. (1999). Musical Visions: Selected Conference Proceedings from 6th National Australian/New Zealand IASPM and Inaugural Arnhem Land Performance Conference, Adelaide, Australia, June 1998. Wakefield Press. ISBN 1862545006.

- Brandon, James R.; Leiter, Samuel L. (2002). Kabuki Plays On-Stage: Villainy and Vengeance, 1773–1799. Univ. of Hawaii Press. ISBN 082482413X.

- Cangia, Flavia (2013). Performing the Buraku: Narratives on Cultures and Everyday Life in Contemporary Japan. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3643801531.

- Carlsen, Spike (2009). A Splintered History of Wood. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0061982774.

- Dean, Matt (2012). The Drum: A History. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810881709.

- de Ferranti, Hugh (2007). "Japan Beating: The making and marketing of professional taiko music in Australia". In Allen, William; Sakamoto, Rumi (eds.). Popular Culture and Globalisation in Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134203741.

- Forss, Matthew J. (2010). "Folk Music". In Lee, Jonathan H.X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. p. 645. ISBN 978-0313350672.

- Gould, Michael (June 1998). "Taiko Classification and Manufacturing" (PDF). Percussive Notes. 36 (3): 12–20.

- Harich-Schneider, Eta (1973). A History of Japanese Music. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0193162032.

- Honda, Yasuji (1984). Tōkyō-to minzoku geinōshi 東京都民俗芸能誌 (in Japanese). Kinseisha 錦正社. OCLC 551310576.

- Hoover, William D. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Postwar Japan. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810854604.

- Ikeda, Nobumichi (1983). Miyakejima no rekishi to minzoku 三宅島の歴史と民俗 (in Japanese). Dentō to Gendaisha 伝統と現代社. OCLC 14968709.

- Ingram, Scott (2004). Japanese Immigrants. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 0816056889.

- Izumi, Masumi (2001). "Reconsidering Ethnic Culture and Community: A Case Study on Japanese Canadian Taiko Drumming". Journal of Asian American Studies. 4 (1): 35–56. doi:10.1353/jaas.2001.0004. S2CID 144105515.

- Izumi, Masumi (2006). "Big Drum: Taiko in the United States". The Journal of American History. 93 (1): 158–161. doi:10.2307/4486067. JSTOR 4486067.

- Kakehi, Hisao; Tamori, Ikuhiro; Schourup, Lawrence (1996). Dictionary of Iconic Expressions in Japanese. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110809044.

- Keene, Jarret (2011). "Drumline". Inside Cirque du Soleil. Fall 2011.

- Kobayashi, Kayo (1998). "Eisa no Bunrui (The Classification of Eisa) エイサーの分類". In Okinawa-shi Kikakubu Heiwa Bunka Shinkōka 沖縄市企画部平和文化振興課 (ed.). Eisā 360-do: Rekishi to Genzai エイサー360度 : 歴史と現在 (in Japanese). Naha Shuppansha 那覇出版社. pp. 36–40. ISBN 4890951113.

- Konagaya, Hideyo (2001). "Taiko as Performance: Creating Japanese American Traditions" (PDF). The Journal of Japanese American Studies. 12: 105–124. ISSN 0288-3570.

- Konagaya, Hideyo (2005). "Performing Manliness: Resistance and Harmony in Japanese American Taiko". In Bronner, Simon J. (ed.). Manly Traditions: The Folk Roots of American Masculinities. Indiana Univ. Press. ISBN 0253217814.

- Konagaya, Hideyo (2007). Performing the Okinawan Woman in Taiko: Gender, folklore, and Identity Politics in Modern Japan (PhD). OCLC 244976556.

- Konagaya, Hideyo (2010). "Taiko Performance". In Lee, Jonathan H.X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. p. 645. ISBN 978-0313350672.

- Kumada, Susumu (2011). "Minzoku geinō Eisa no hen'yō to tenkai 民族芸能エイサーの変容と展開". Okinawa no minzoku geinō ron 沖縄の民俗芸能論 (in Japanese). Naha Shuppansha 那覇出版社. pp. 193–244. OCLC 47600697.

- Lacashire, Terence A. (2011). An Introduction to Japanese Folk Performing Arts. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409431336.

- Li, Xiaoping (2011). Voices Rising: Asian Canadian Cultural Activism. Univ. of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0774841368.

- Lorenz, Shanna (2007). "Japanese in the Samba": Japanese Brazilian Musical Citizenship, Racial Consciousness, and Transnational Migration. Univ. of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0549451983.

- Malm, William P. (May 1960). "An Introduction to Taiko Drum Music in the Japanese No Drama". Ethnomusicology. 4 (2): 75–78. doi:10.2307/924267. JSTOR 924267.

- Malm, William P. (1963). Nagauta: The Heart of Kabuki Music. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 1462913059.

- Malm, William P. (1986). Six Hidden Views of Japanese Music. Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520050452.

- Malm, William P. (2000). Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments (1st ed.). Kodansha International. ISBN 4770023952.

- McLeod, Ken (2013). We Are the Champions: The Politics of Sports and Popular Music. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409408642.

- Miki, Minoru (2008). Regan, Marty (ed.). Composing for Japanese Instruments. Univ. of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1580462730.

- Miller, Terry E.; Shahriari, Andrew (2014). World Music: A Global Journey. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317974604.

- Minor, William (2003). Jazz Journeys to Japan: The Heart Within. Univ. of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472113453.

- Nelson, Stephen G. (2007). Tokita, Alison; Hughes, David W. (eds.). The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music (Reprint ed.). Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754656999.

- Nomura, Gail M. (2005). Fiset, Louis; Nomura, Gail M. (eds.). Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest Japanese Americans & Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with Univ. of Washington Press. ISBN 0295800097.

- Piggott, Francis Taylor (1971). The music and musical instruments of Japan (Unabridged republication of the Yokohama [usw.] (1909) 2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 030670160X.

- Powell, Kimberly (2012). "Inside-Out and Outside-In: Participant Observation in Taiko Drumming". In Spindler, George; Hammond, Lorie (eds.). Innovations in Educational Ethnography: Theories, Methods, and Results. Psychology Press. pp. 33–64. ISBN 978-1136872693.

- Powell, Kimberly (2012). "The Drum in the Dojo". In Dixon-Román, Ezekiel; Gordon, Edmund W. (eds.). Thinking Comprehensively About Education: Spaces of Educative Possibility and their Implications for Public Policy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136318474.

- Raz, Jacob (1983). Audience and Actors: A Study of Their Interaction in the Japanese Traditional Theatre. Brill Archive. ISBN 9004068864.

- Roth, Louis Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0674017536.

- Schuller, Gunther (1989). Musings: The Musical Worlds of Gunther Schuller. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 019972363X.

- Terada, Yoshitaka (2001). Terada, Yoshitaka (ed.). "Transcending boundaries: Asian Musics in North America". Shifting Identities of Taiko Music in North America. 22: 37–60. ISSN 1340-6787.

- Terada, Yoshitaka (2013). "Rooted as Banyan Trees: Eisā and the Okinawan Diaspora". In Rice, Timothy (ed.). Ethnomusicological Encounters with Music and Musicians: Essays in Honor of Robert Garfias (revised ed.). Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409494782.

- Thornbury, Barbara (2013). America's Japan and Japan's Performing Arts: Cultural Mobility and Exchange in New York, 1952–2011. Univ. of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472029280.

- Titon, Jeff Todd; Fujie, Linda, eds. (2005). Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0534627579.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2008). Samurai Armies: 1467–1649. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1846033513.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2012). War in Japan 1467–1615. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1782000181.

- Tusler, Mark (2003). Sounds and Sights of Power: Ensemble Taiko Drumming (Kumi Daiko) Pedagogy in California and the Conceptualization of Power (PhD). Univ. of California, Santa Barbara. OCLC 768102165.

- Varian, Heidi (2005). The Way of Taiko (1st ed.). Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 188065699X.

- Varian, Heidi (2013). The Way of Taiko (2nd ed.). Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1611720129.

- Wald, Elijah; Vartoogian, Linda (2007). Global Minstrels: Voices of World Music. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415979290.

- Webb, Michael; Seddon, Frederick A. (2012). "Musical Instrument Learning, Music Ensembles, and Musicianship in a Global and Digital Age". In McPherson, Gary E.; Welch, Graham F. (eds.). The Oxford handbook of music education. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0199730810.

- Wong, Deborah (2000). "Taiko and the Asian/American Body: Drums, Rising Sun, and the Question of Gender". The World of Music. 42 (3): 67–78. JSTOR 41692766. OCLC 717224426.

- Wong, Deborah (2004). Speak It Louder: Asian Americans Making Music. Routledge. ISBN 0203497279.

- Yoon, Paul Jong-Chul (2001). "'She's Really Become Japanese Now!': Taiko Drumming and Asian American Identifications". American Music. 19 (4): 417–438. doi:10.2307/3052419. JSTOR 3052419.

External links

- The Nippon Taiko Foundation, part of the Agency for Cultural Affairs