Taíno

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities.[2][3] At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the principal inhabitants of most of what is now Cuba, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The Lucayan branch of the Taíno were the first New World peoples encountered by Christopher Columbus, in the Bahama Archipelago on October 12, 1492. The Taíno spoke a dialect of the Arawakan language group.[4] They lived in agricultural societies ruled by caciques with fixed settlements and a matrilineal system of kinship and inheritance. Taíno religion centered on the worship of zemis.[5]

.jpg.webp) Statue of Agüeybaná II, "El Bravo" in Ponce, Puerto Rico[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Bahamas | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, Creole languages Taíno (historically) | |

| Religion | |

| Native American religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lokono, Kalinago, Garifuna, Igneri, Guanahatabey |

Some anthropologists and historians have claimed that the Taíno were exterminated centuries ago[6][7][8] or they gradually went extinct by blending into a shared identity with African and Spanish cultures.[9] However, many people today identify as Taíno or claim Taíno descent, most notably in subsections of the Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican nationalities.[10] Many Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans have Taíno mitochondrial DNA, showing that they are descendants through the direct female line.[11][12] While some communities claim an unbroken cultural heritage to the old Taíno peoples, others are revivalist communities who seek to incorporate Taíno culture into their lives.

Terminology

Various scholars have addressed the question of who were the native inhabitants of the Caribbean islands to which Columbus voyaged in 1492. They face difficulties, as European accounts cannot be read as objective evidence of a native Caribbean social reality.[13] The people who inhabited most of the Greater Antilles when Europeans arrived in the New World have been denominated as Taínos, a term coined by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1836.[2] Taíno is not a universally accepted denomination—it was not the name this people called themselves originally, and there is still uncertainty about their attributes and the boundaries of the territory they occupied.[14]

The term nitaino or nitayno, from which "Taíno" derived, referred to an elite social class, not to an ethnic group. No 16th-century Spanish documents use this word to refer to the tribal affiliation or ethnicity of the natives of the Greater Antilles. The word tayno or taíno, with the meaning "good" or "prudent", was mentioned twice in an account of Columbus's second voyage by his physician, Diego Álvarez Chanca, while in Guadeloupe. José R. Oliver writes that the natives of Borinquén, who had been captured by the Caribs of Guadeloupe and who wanted to escape on Spanish ships to return home to Puerto Rico, used the term to indicate that they were the "good men", as opposed to the Caribs.[2]

Contrarily, according to Peter Hulme, most translators appear to agree that the word taino was used by Columbus's sailors, not by the islanders who greeted them, although there is room for interpretation. The sailors may have been saying the only word they knew in a native Caribbean tongue, or perhaps they were indicating to the "commoners" on the shore that they were taíno, i.e., important people, from elsewhere and thus entitled to deference. If taíno was being used here to denote ethnicity, then it was used by the Spanish sailors to indicate that they were "not Carib", and gives no evidence of self-identification by the native people.[14]

According to José Barreiro, a direct translation of the word "Taíno" signified "men of the good".[15] The Taíno people, or Taíno culture, has been classified by some authorities as belonging to the Arawak. Their language is considered to have belonged to the Arawak language family, the languages of which were historically present throughout the Caribbean, and much of Central and South America.

In 1871, early ethnohistorian Daniel Garrison Brinton referred to the Taíno people as the "Island Arawak", expressing their connection to the continental peoples.[16] Since then, numerous scholars and writers have referred to the indigenous group as "Arawaks" or "Island Arawaks". However, contemporary scholars (such as Irving Rouse and Basil Reid) have recognized that the Taíno developed a distinct language and culture from the Arawak of South America.[17][18]

Taíno and Arawak appellations have been used with numerous and contradictory meanings by writers, travelers, historians, linguists, and anthropologists. Often they were used interchangeably: "Taíno" was applied to the Greater Antillean natives only, but could include the Bahamian or the Leeward Islands natives, excluding the Puerto Rican and Leeward nations. Similarly, "Island Taíno" has been used to refer only to those living in the Windward Islands, or to the northern Caribbean inhabitants, as well as to the indigenous population of all the Caribbean islands.

Modern historians, linguists and anthropologists now hold that the term Taíno should refer to all the Taíno/Arawak nations except the Caribs, who are not seen as belonging to the same people. Linguists continue to debate whether the Carib language is an Arawakan dialect or creole language. They also speculate that it was an independent language isolate, with an Arawakan pidgin used for communication purposes with other peoples, as in trading.

Rouse classifies all inhabitants of the Greater Antilles as Taíno (except the western tip of Cuba and small pockets of Hispaniola), the Lucayan archipelago, and the northern Lesser Antilles. He subdivides the Taíno into three main groups: Classic Taíno, from most of Hispaniola and all of Puerto Rico; Western Taíno, or sub-Taíno, from Jamaica, most of Cuba, and the Lucayan archipelago; and Eastern Taíno, from the Virgin Islands to Montserrat.[19]

Origins

Two schools of thought have emerged regarding the origin of the indigenous people of the Caribbean.

- One group of scholars contends that the ancestors of the Taíno were Arawak speakers who came from the center of the Amazon Basin. This is indicated by linguistic, cultural and ceramic evidence. They migrated to the Orinoco valley on the north coast. From there they reached the Caribbean by way of what is now Guyana and Venezuela into Trinidad, migrating along the Lesser Antilles to Cuba and the Bahamian archipelago. Evidence that supports the theory includes the tracing of the ancestral cultures of this people to the Orinoco Valley, and their languages to the Amazon Basin.[20][21][22]

- The alternate theory, known as the circum-Caribbean theory, contends that the ancestors of the Taíno diffused from the Colombian Andes. Julian H. Steward, who originated this concept, suggests a migration from the Andes to the Caribbean and a parallel migration into Central America and into the Guianas, Venezuela, and the Amazon Basin of South America.[20]

Taíno culture as documented is believed to have developed in the Caribbean. The Taíno creation story says that they emerged from caves in a sacred mountain on present-day Hispaniola.[23] In Puerto Rico, 21st-century studies have shown that a high proportion of people have Amerindian mtDNA. Of the two major haplotypes found, one does not exist in the Taíno ancestral group, so other Native American people are also among the genetic ancestors.[21][24]

DNA studies changed some of the traditional beliefs about pre-Columbian indigenous history. According to National Geographic, "studies confirm that a wave of pottery-making farmers—known as Ceramic Age people—set out in canoes from the northeastern coast of South America starting some 2,500 years ago and island-hopped across the Caribbean. They were not, however, the first colonizers. On many islands they encountered a foraging people who arrived some 6,000 or 7,000 years ago...The ceramicists, who are related to today's Arawak-speaking peoples, supplanted the earlier foraging inhabitants—presumably through disease or violence—as they settled new islands."[25]

Culture

Taíno society was divided into two classes: naborias (commoners) and nitaínos (nobles). They were governed by male chiefs known as caciques, who inherited their position through their mother's noble line. (This was a matrilineal kinship system, with social status passed through the female lines.) The nitaínos functioned as sub-caciques in villages, overseeing the work of naborias. Caciques were advised by priests/healers known as bohiques. Caciques enjoyed the privilege of wearing golden pendants called guanín, living in square bohíos, instead of the round ones of ordinary villagers, and sitting on wooden stools to be above the guests they received.[26] Bohiques were extolled for their healing powers and ability to speak with deities. They were consulted and granted the Taíno permission to engage in important tasks.

The Taíno had a matrilineal system of kinship, descent, and inheritance. When a male heir did not exist, the inheritance or succession would go to the oldest male child of the sister of the deceased. Post-marital residence was avunculocal, meaning a newly married couple lived in the household of the maternal uncle. He was more important in the lives of his niece's children than their biological father; the uncle introduced the boys to men's societies in his sister and his family's clan. Some Taíno practiced polygamy. Men, and sometimes women, might have two or three spouses. Ramón Pané, a Catholic friar who traveled with Columbus on his second voyage and was tasked with learning the indigenous people's language and customs, wrote in the 16th century that caciques tended to have two or three wives and the principal ones had as many as 10, 15, or 20.[27][28]

The Taíno women were skilled in agriculture, which the people depended on. The men also fished and hunted, making fishing nets and ropes from cotton and palm. Their dugout canoes (kanoa) were of various sizes and could hold from 2 to 150 people; an average-sized canoe would hold 15–20. They used bows and arrows for hunting and developed the use of poisons on their arrowheads.

Taíno women commonly wore their hair with bangs in front and longer in back, and they occasionally wore gold jewelry, paint, and/or shells. Taíno men and unmarried women did not usually wear clothes, but went naked. After marriage, women wore a small cotton apron, called a nagua.[29]

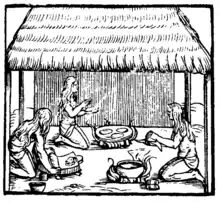

The Taíno lived in settlements called yucayeques, which varied in size depending on the location. Those in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola were the largest and those in the Bahamas were the smallest. In the center of a typical village was a central plaza, used for various social activities, such as games, festivals, religious rituals, and public ceremonies. These plazas had many shapes, including oval, rectangular, narrow, and elongated. Ceremonies where the deeds of the ancestors were celebrated, called areitos, were performed here.[30]

Often, the general population lived in large circular buildings (bohios), constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. These houses, built surrounding the central plaza, could hold 10–15 families each.[31] The cacique and his family lived in rectangular buildings (caney) of similar construction, with wooden porches. Taíno home furnishings included cotton hammocks (hamaca), sleeping and sitting mats made of palms, wooden chairs (dujo or duho) with woven seats and platforms, and cradles for children.

The Taíno played a ceremonial ball game called batey. Opposing teams had 10 to 30 players per team and used a solid rubber ball. Normally, the teams were composed of men, but occasionally women played the game as well.[32] The Classic Taíno played in the village's center plaza or on especially designed rectangular ball courts called batey. Games on the batey are believed to have been used for conflict resolution between communities. The most elaborate ball courts are found at chiefdom boundaries.[30] Often, chiefs made wagers on the possible outcome of a game.[32]

Taíno spoke an Arawakan language and used an early form of writing Proto-writing in the form of petroglyph,[33]as found in Taíno archeological sites in the West Indies.[34]

Some words they used, such as barbacoa ("barbecue"), hamaca ("hammock"), kanoa ("canoe"), tabaco ("tobacco"), sabana (savanna) and juracán ("hurricane"), have been incorporated into other languages.[35]

For warfare, the men made wooden war clubs, which they called a macana. It was about one inch thick and was similar to the coco macaque.

The Taínos decorated and applied war paint to their face to appear fierce towards their enemies. They ingested substances at religious ceremonies and invoked zemis.[36]

Cacicazgo/society

The Taíno were the most culturally advanced of the Arawak group to settle in what is now Puerto Rico.[38] Individuals and kinship groups that previously had some prestige and rank in the tribe began to occupy the hierarchical position that would give way to the cacicazgo.[39] The Taíno founded settlements around villages and organized their chiefdoms, or cacicazgos, into a confederation.[40]

The Taíno society, as described by the Spanish chroniclers, was composed of four social classes: the cacique, the nitaínos, the behiques, and the naborias.[39] According to archeological evidence, the Taíno islands were able to support a high number of people for approximately 1,500 years.[41] Every individual living in the Taíno society had a task to do. The Taíno believed that everyone living in their islands should eat properly.[41] They followed a very efficient nature harvesting and agricultural production system.[41] Either people were hunting, searching for food, or doing other productive tasks.[41]

Tribal groups settled in villages under a chieftain, known as cacique, or cacica if the ruler was a woman. Many women whom the Spaniards called cacicas were not always rulers in their own right, but were mistakenly acknowledged as such because they were the wives of caciques. Chiefs were chosen from the nitaínos and generally obtained their power from the maternal line. A male ruler was more likely to be succeeded by his sister's children than his own, unless their mother's lineage allowed them to succeed in their own right.[42]

The chiefs had both temporal and spiritual functions. They were expected to ensure the welfare of the tribe and to protect it from harm from both natural and supernatural forces.[43] They were also expected to direct and manage the food production process. The cacique's power came from the number of villages he controlled and was based on a network of alliances related to family, matrimonial, and ceremonial ties. According to an early 20th-century Smithsonian study, these alliances showed unity of the indigenous communities in a territory;[44] they would band together as a defensive strategy to face external threats, such as the attacks by the Caribs on communities in Puerto Rico.[45]

The practice of polygamy enabled the cacique to have women and create family alliances in different localities, thus extending his power. As a symbol of his status, the cacique carried a guanín of South American origin, made of an alloy of gold and copper. This symbolized the first Taíno mythical cacique Anacacuya, whose name means "star of the center", or "central spirit." In addition to the guanín, the cacique used other artifacts and adornments to serve to identify his role. Some examples are tunics of cotton and rare feathers, crowns and masks or "guaizas" of cotton with feathers; colored stones, shells or gold; cotton woven belts; and necklaces of snail beads or stones, with small masks of gold or other material.[39]

Under the cacique, the social organization was composed of two tiers: The nitaínos at the top and the naborias at the bottom.[38] The nitaínos were considered the nobles of the tribes. They were made up of warriors and family of the cacique.[46] Advisers who assisted in operational matters of assigning and supervising communal work, planting and harvesting crops, and keeping peace among the village's inhabitants, were selected from among the nitaínos.[47] The naborias were the more numerous working peasants of the lower class.[46]

The behiques were priests who represented religious beliefs.[46] Behiques dealt with negotiating with angry or indifferent gods as the accepted lords of the spiritual world. The behiques were expected to communicate with the gods, to soothe them when they were angry, and to intercede on the tribe's behalf. It was their duty to cure the sick, heal the wounded, and interpret the will of the gods in ways that would satisfy the expectations of the tribe. Before carrying out these functions, the behiques performed certain cleansing and purifying rituals, such as fasting for several days and inhaling sacred tobacco snuff.[43]

Food and agriculture

Taíno staples included vegetables, fruit, meat, and fish. There were no large animals native to the Caribbean, but they captured and ate small animals, such as hutias and other mammals, earthworms, lizards, turtles, and birds. Manatees were speared and fish were caught in nets, speared, trapped in weirs, or caught with hook and line. Wild parrots were decoyed with domesticated birds, and iguanas were taken from trees and other vegetation. The Taíno stored live animals until they were ready to be consumed: fish and turtles were stored in weirs, hutias and dogs were stored in corrals.[48]

The Taíno people became very skilled fishermen. One method used was to hook a remora, also known as a suckerfish, to a line secured to a canoe and wait for the fish to attach itself to a larger fish or even a sea turtle. Once this happened, some of the Taíno would dive into the water to assist in retrieving the catch. Another method used by the Taínos was to shred the stems and roots of poisonous senna plants and throw them into nearby streams or rivers. Upon eating the bait, the fish were stunned, allowing boys time enough to collect them. This toxin did not affect the edibility of the fish. The Taíno also collected mussels and oysters in shallow waters within the exposed mangrove roots.[49] Some young boys hunted waterfowl from flocks that "darkened the sun", according to Christopher Columbus.[41]

Taíno groups in the more developed islands, such as Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, and Jamaica, relied more on agriculture (farming and other jobs). Fields for important root crops, such as the staple yuca, were prepared by heaping up mounds of soil, called conucos. This improved soil drainage and fertility as well as delaying erosion, allowed for longer storage of crops in the ground. Less important crops such as corn were raised in simple clearings created by slash and burn technique. Typically, conucos were three feet high and nine feet in circumference and were arranged in rows.[50] The primary root crop was yuca or cassava, a woody shrub cultivated for its edible and starchy tuberous root. It was planted using a coa, a kind of hoe made completely from wood. Women processed the poisonous variety of cassava by squeezing it to extract the toxic juices. Then they would grind the roots into flour for baking bread. Batata (sweet potato) was the next most important root crop.[50]

Contrary to mainland practices, corn was not ground into flour and baked into bread, but was cooked and eaten off the cob. Corn bread becomes moldy faster than cassava bread in the high humidity of the Caribbean. Corn also was used to make an alcoholic beverage known as chicha.[51] The Taíno grew squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, and pineapples. Tobacco, calabashes (bottle gourds), and cotton were grown around the houses. Other fruits and vegetables, such as palm nuts, guavas, and Zamia roots, were collected from the wild.[50]

Spirituality

Walters Art Museum

Taíno spirituality centered on the worship of zemís (spirits or ancestors). The major Taíno zemis are Atabey and her son, Yúcahu. Atabey was the zemi of the moon, fresh waters, and fertility. Other names for her include Atabei, Atabeyra, Atabex, and Guimazoa. The Taínos of Quisqueya (Dominican Republic) called her son, "Yucahú Bagua Maorocotí", which means "White Yuca, great and powerful as the sea and the mountains". He was the spirit of cassava, the zemi of cassava – the Taínos' main crop – and the sea.

Guabancex was the non-nurturing aspect of the zemi Atabey who had control over natural disasters. She is identified as the goddess of the hurricanes or as the zemi of storms. Guabancex had twin sons: Guataubá, a messenger who created hurricane winds, and Coatrisquie, who created floodwaters.[52]

Iguanaboína was the goddess of the good weather. She also had twin sons: Boinayel, the messenger of rain, and Marohu, the spirit of clear skies.[53]

The minor Taíno zemis related to the growing of cassava, the process of life, creation, and death. Baibrama was a minor zemi worshiped for his assistance in growing cassava and curing people from its poisonous juice. Boinayel and his twin brother Márohu were the zemis of rain and fair weather, respectively.[54]

Maquetaurie Guayaba or Maketaori Guayaba was the zemi of Coaybay or Coabey, the land of the dead. Opiyelguabirán', a dog-shaped zemi, watched over the dead. Deminán Caracaracol, a male cultural hero from whom the Taíno believed themselves to be descended, was worshipped as a zemí.[54] Macocael was a cultural hero worshipped as a zemi, who had failed to guard the mountain from which human beings arose. He was punished by being turned into stone, or a bird, a frog, or a reptile, depending on interpretation of the myth.

Lombards Museum

Zemí was also the name the people gave to their physical representations of the Zemis, whether objects or drawings. They were made in many forms and materials and have been found in a variety of settings. The majority of zemís were crafted from wood, but stone, bone, shell, pottery, and cotton were used as well.[55] Zemí petroglyphs were carved on rocks in streams, ball courts, and on stalagmites in caves, such as the cemi carved into a stalagmite in a cave in La Patana, Cuba.[56] Cemí pictographs were found on secular objects such as pottery, and on tattoos. Yucahú, the zemi of cassava, was represented with a three-pointed zemí, which could be found in conucos to increase the yield of cassava. Wood and stone zemís have been found in caves in Hispaniola and Jamaica.[57] Cemís are sometimes represented by toads, turtles, fish, snakes, and various abstract and human-like faces.

Brooklyn Museum

Some zemís are accompanied by a small table or tray, which is believed to be a receptacle for hallucinogenic snuff called cohoba, prepared from the beans of a species of Piptadenia tree. These trays have been found with ornately carved snuff tubes. Before certain ceremonies, Taínos would purify themselves, either by inducing vomiting (with a swallowing stick) or by fasting.[58] After communal bread was served, first to the zemí, then to the cacique, and then to the common people, the people would sing the village epic to the accompaniment of maraca and other instruments.

One Taíno oral tradition explains that the Sun and Moon came out of caves. Another story tells of the first people, who once lived in caves and only came out at night, because it was believed that the Sun would transform them; a sentry became a giant stone at the mouth of the cave, others became birds or trees. The Taíno believed they were descended from the union of the cultural hero Deminán Caracaracol and a female turtle (who was born of the former's back after being afflicted with a blister). The origin of the oceans is described in the story of a huge flood that occurred when the great spirit Yaya murdered his son Yayael (who was about to murder his father). The father put his son's bones into a gourd or calabash. When the bones turned into fish, the gourd broke, an accident caused by Deminán Caracaracol, and all the water of the world came pouring out.

Taínos believed that Jupias, the souls of the dead, would go to Coaybay, the underworld, and there they rest by day. At night they would assume the form of bats and eat the guava fruit.

Spanish and Taíno

.jpg.webp)

Columbus and the crew of his ship were the first Europeans to encounter the Taíno people, as they landed in The Bahamas on October 12, 1492. After their first interaction, Columbus described the Taínos as a physically tall, well-proportioned people, with noble and kind personalities.

In his diary, Columbus wrote:

They traded with us and gave us everything they had, with good will ... they took great delight in pleasing us ... They are very gentle and without knowledge of what is evil; nor do they murder or steal...Your highness may believe that in all the world there can be no better people ... They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing.[59]

At this time, the neighbors of the Taíno were the Guanahatabeys in the western tip of Cuba, the Island-Caribs in the Lesser Antilles from Guadeloupe to Grenada, and the Calusa and Ais nations of Florida. Guanahaní was the Taíno name for the island that Columbus renamed as San Salvador (Spanish for "Holy Savior"). Columbus called the Taíno "Indians", a reference that has grown to encompass all the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere. A group of about 24 Taíno people were forced to accompany Columbus on his 1494 return voyage to Spain.[60]

On Columbus' second voyage in 1493, he began to require tribute from the Taíno in Hispaniola. According to Kirkpatrick Sale, each adult over 14 years of age was expected to deliver a hawks bell full of gold every three months, or when this was lacking, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton. If this tribute was not brought, the Spanish cut off the hands of the Taíno and left them to bleed to death.[61] These cruel practices inspired many revolts by the Taíno and campaigns against the Spanish — some being successful, some not.

In 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican missionary in Hispaniola, became the first European to publicly denounce the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the island and the Encomienda system.[62]

In 1511, several caciques in Puerto Rico, such as Agüeybaná II, Arasibo, Hayuya, Jumacao, Urayoán, Guarionex, and Orocobix, allied with the Carib and tried to oust the Spaniards. The revolt was suppressed by the Indio-Spanish forces of Governor Juan Ponce de León.[63] Hatuey, a Taíno chieftain who had fled from Hispaniola to Cuba with 400 natives to unite the Cuban natives, was burned at the stake on February 2, 1512.

In Hispaniola, a Taíno chieftain named Enriquillo mobilized more than 3,000 Taíno in a successful rebellion in the 1520s. These Taíno were accorded land and a charter from the royal administration. Despite the small Spanish military presence in the region, they often used diplomatic divisions and, with help from powerful native allies, controlled most of the region.[64][65] In exchange for a seasonal salary, religious and language education, the Taíno were required to work for Spanish and Indian land owners. This system of labor was part of the encomienda.[66]

Women

Taíno society was based on a matrilineal system and descent was traced through the mother. Women lived in village groups containing their children. The men lived separately. As a result, Taíno women had extensive control over their lives, their co-villagers, and their bodies.[67] The Taínos told Columbus that another indigenous tribe, Caribs, were fierce warriors, who made frequent raids on the Taínos, often capturing their women.[68][69]

Taíno women played an important role in intercultural interaction between Spaniards and the Taíno people. When Taíno men were away fighting intervention from other groups, women assumed the roles of primary food producers or ritual specialists.[70] Women appeared to have participated in all levels of the Taíno political hierarchy, occupying roles as high up as being cazicas.[71] Potentially, this meant Taíno women could make important choices for the village and could assign tasks to tribe members.[72] There is evidence that suggests that the women who were wealthiest among the tribe collected crafted goods, that they would then use for trade or as gifts.

Despite women being seemingly independent in Taíno society, during the era of contact, Spaniards took Taíno women as an exchange item, putting them in a non-autonomous position. Diego Álvarez Chanca, a physician who traveled with Christopher Columbus, reported in a letter that Spaniards took as many women as they possibly could and kept them as concubines. Some sources report that, despite women being free and powerful before the contact era, they became the first commodities up for Spaniards to trade, or often, steal. This marked the beginning of a lifetime of kidnapping and abuse of Taíno women.[73]

Depopulation

Early population estimates of Hispaniola, probably the most populous island inhabited by Taínos, range from 10,000 to 1,000,000 people.[74] The maximum estimates for Jamaica and Puerto Rico are 600,000 people.[19] A 2020 genetic analysis estimated the population to be no more than a few tens of thousands of people.[75][76] Spanish priest and defender of the Taíno, Bartolomé de las Casas (who had lived in Santo Domingo), wrote in his 1561 multi-volume History of the Indies:[77]

There were 60,000 people living on this island [when I arrived in 1508], including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this?

Researchers today doubt Las Casas' figures for the pre-contact levels of the Taíno population, considering them an exaggeration.[78] For example, Karen Anderson Córdova estimates a maximum of 500,000 people inhabiting the island.[79] They had no resistance to Old World diseases, notably smallpox. The encomienda system brought many Taíno to work in the fields and mines in exchange for Spanish protection,[80] education, and a seasonal salary.[81] Under the pretense of searching for gold and other materials,[82] many Spaniards took advantage of the regions now under control of the anaborios and Spanish encomenderos to exploit the native population by seizing their land and wealth. Historian David Stannard characterizes the encomienda as a genocidal system that "had driven many millions of native peoples in Central and South America to early and agonizing deaths."[83] It would take some time before the Taíno revolted against their oppressors — both Indian and Spanish alike — and many military campaigns before Emperor Charles V eradicated the encomienda system as a form of slavery.[84][85]

Disease obviously played a significant role in the destruction of the indigenous population, but forced labor was also one of the chief reasons behind the depopulation of the Taíno.[86] The first man to introduce this forced labor among the Taínos was the leader of the European colonization of Puerto Rico, Ponce de León.[86] Such forced labor eventually led to the Taíno rebellions, in which the Spaniards responded with violent military expeditions known as cabalgadas. The purpose of the military expeditions was to capture the indigenous people. This violence by the Spaniards was a reason why there was a decline in the Taíno population since it forced many of them to emigrate to other islands and the mainland.[87]

In thirty years, between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died.[88][86] Because of the increased number of people (Spanish) on the island, there was a higher demand for food. Taíno cultivation was converted to Spanish methods. In hopes of frustrating the Spanish, some Taínos refused to plant or harvest their crops. The supply of food became so low in 1495 and 1496 that some 50,000 died from famine.[89] Historians have determined that the massive decline was due more to infectious disease outbreaks than any warfare or direct attacks.[90][91] By 1507, their numbers had shrunk to 60,000. Scholars believe that epidemic disease (smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus) was an overwhelming cause of the population decline of the indigenous people,[92] and also attributed a "large number of Taíno deaths...to the continuing bondage systems" that existed.[93][94] Academics, such as historian Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis, assert that disease alone does not explain the total destruction of indigenous populations of Hispaniola. While the populations of Europe rebounded following the devastating population decline associated with the Black Death, there was no such rebound for the indigenous populations of the Caribbean. He concludes that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, meaning perhaps they didn't spread as fast as initially believed, and that unlike Europeans, the indigenous populations were subjected to slavery, exploitation, and forced labor in gold and silver mines on an enormous scale.[95] Reséndez says that "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous people of the Caribbean.[96] Anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that a third of indigenous workers died every six months from lethal forced labor in these mines.[97]

Taíno descendants today

Modern Taíno communities

Evidence suggests that some Taíno women and African men intermarried and lived in relatively isolated Maroon communities in the interior of the islands, where they developed into a mixed-race population who were relatively independent of Spanish authorities. For instance, when the colony of Jamaica was under the rule of Spain (known then as the colony of Santiago), both Taíno men and women fled to the Bastidas Mountains (currently known as the Blue Mountains). There the Taíno intermingled with escaped enslaved Africans. They were among the ancestors of the Jamaican Maroons of the east, including those communities led by Juan de Bolas and Juan de Serras. The Maroons of Moore Town claim descent from the Taíno.[98]

Frank Moya Pons, a Dominican historian, documented that Spanish colonists intermarried with Taíno women. Over time, some of their mixed-race descendants intermarried with Africans, creating a tripartite Creole culture. Census records from the year 1514 reveal that 40% of Spanish men on the island of Hispaniola had Taíno wives.[99] But ethnohistorian Lynne Guitar writes that Spanish documents declared the Taíno to be extinct in the 16th century, as early as 1550.[100]

Scholars also note that contemporary rural Dominicans retain elements of Taíno culture: including linguistic features, agricultural practices, food ways, medicine, fishing practices, technology, architecture, oral history, and religious views. Often urbanites have considered such cultural traits as backward, however.[100]

Communities of indigenous people of substantial Taíno ancestry have survived in isolated parts of eastern Cuba (including parts of Yateras and Baracoa) into the present, who preserve cultural practices of Taíno origin.[101][102]

At the 2010 U.S. census, 1,098 people in Puerto Rico identified as "Puerto Rican Indian," 1,410 identified as "Spanish American Indian," and 9,399 identified as "Taíno." In total, 35,856 Puerto Ricans identified as Native American.[103]

It is estimated that the population of the Taíno people in the 21st century is about 1.2 million people.

Taíno revivalist communities

As of 2006, there were a couple of dozen activist Taíno organizations from Florida to Puerto Rico and California to New York with growing memberships numbering in the thousands. These efforts are known as the "Taíno restoration", a revival movement for Taíno culture that seeks official recognition of the survival of the Taíno people.[104]

In Puerto Rico, the history of the Taíno is being taught in schools and children are encouraged to celebrate the culture and identity of Taíno through dance, costumes and crafts. Martínez Cruzado, a geneticist at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez said celebrating and learning about their Taíno roots is helping Puerto Ricans feel connected to one another.[105]

While the scholar Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel sees the development of the Neo-Taíno movement in Puerto Rico as a useful counter to the domination of the island by the United States and the Spanish legacies of island society, she also notes that the Neo-Taíno movement in Puerto Rico "could be seen as a useless anachronistic reinvention of a 'Boricua coqui' identity can also be conceived as a productive example of Spivak's 'strategic essentialism'".[106]

DNA of Taíno descendants

In 2018, a DNA study mapped the genome of the tooth belonging to an 8th- to 10th–century woman from the Bahamas.[107] "Comparing the ancient Bahamian genome to those of contemporary Puerto Ricans, the researchers found that they were more closely related to the ancient Taíno than any other indigenous group in the Americas."[107] The research team compared the genome to 104 Puerto Ricans who participated in the 1000 Genomes Project (2008), who had 10 to 15 percent Indigenous American ancestry, which was "closely related to the ancient Bahamian genome."[107][108]

DNA evidence shows that a large proportion of the current populations of the Greater Antilles have Taíno ancestry, with 61% of Puerto Ricans, up to 30% of Dominicans, and 33% of Cubans having mitochondrial DNA of Taíno origin.[109]

Sixteen autosomal studies of peoples in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and its diaspora (mostly Puerto Ricans) have shown that between 10–20% of their DNA is indigenous. Some individuals have slightly higher scores, and others have lower scores, or no indigenous DNA at all.[110] A recent study of a population in eastern Puerto Rico, where the majority of persons tested claimed Taíno ancestry and pedigree, showed that they had 61% mtDNA (distant maternal ancestry) from the Taíno, and 0% Y-chromosome DNA (distant paternal ancestry) from the indigenous people. This demonstrated the anticipated creole population formed from the Taíno, Spanish and Africans.[111] Histories of the Caribbean commonly describe the Taíno as extinct, due to being killed off by disease, slavery, and war with the Spaniards. Some present-day residents of the Caribbean self-identify as Taíno, and claim that Taíno culture and identity have survived into the present.[112] Groups advocating this point of view are known as Neo-Taínos, and are also established in the Puerto Rican communities located in New Jersey and New York. A few Neo-Taíno groups are pushing not only for recognition, but respect for their cultural assets.[113]

A genetic study published in 2018 provided some evidence of a present-day Caribbean population being related to the Taínos. DNA was extracted from a tooth of a 1,000-year-old female skeleton found in Preacher's Cave on Eleuthera, and the genetic results show that she is most closely related to present-day Arawakan speakers from northern South America. The study's authors write that this demonstrates continuity between pre-contact populations and present-day Latino populations in the Caribbean.[114][115] Today, Taínos from places such as the diaspora in the United States and the islands, are gathering together.[116]

See also

- Ciboney

- Garifuna

- Hupia, spirit of the dead

- Indigenous Amerindian genetics

- List of Taínos

- Pomier Caves

- Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Center

- West Indies

- Yamaye

References

- Eli D. Oquendo-Rodríguez. Pablo L. Crespo-Vargas, editor. A Orillas del Mar Caribe: Boceto histórico de la Playa de Ponce - Desde sus primeros habitantes hasta principios del siglo XX. First edition. June, 2017. Editorial Akelarre. Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones del Sur Oeste de Puerto Rico (CEISCO). Lajas, Puerto Rico. Page 15. ISBN 978-1547284931

- Oliver, José R. (2009). "Who Were the Taínos and Where Did They Come From? Believers of Ceíism". Caciques and Cemi Idols: The Web Spun by Taino Rulers Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. University of Alabama Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8173-5515-9.

- Rouse 1992, p. 161.

- "Taino". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2018.

- Rouse 1992, p. 13-15.

- "Genes of 'extinct' Caribbean islanders found in living people". www.science.org. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- Poole, Robert M. (October 2011). "What Became of the Taíno?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- "On Indigenous Peoples' Day, meet the survivors of a 'paper genocide'". History. 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- Rouse 1992, p. 161-164.

- "The Taíno were written off as extinct. Until now". Newsweek.com. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-05-08. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- Schroeder, Hannes; Sikora, Martin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Cassidy, Lara M.; Maisano Delser, Pierpaolo; Sandoval Velasco, Marcela; Schraiber, Joshua G.; Rasmussen, Simon; Homburger, Julian R.; Ávila-Arcos, María C.; Allentoft, Morten E. (2018-03-06). "Origins and genetic legacies of the Caribbean Taino". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (10): 2341–2346. doi:10.1073/pnas.1716839115. PMC 5877975. PMID 29463742.

- Poole, Robert M. (October 2011). "What Became of the Taíno". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Hulme, Peter (1 January 1993). "Making Sense of the Native Caribbean". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 67 (3–4): 211. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002665.

- Hulme, Peter (1 January 1993). "Making Sense of the Native Caribbean". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 67 (3–4): 199–202. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002665.

- Barreiro, José (1998). Rethinking Columbus – The Taínos: "Men of the Good". Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Rethinking Schools, Ltd. pp. 106. ISBN 978-0-942961-20-1.

- Daniel Garrison Brinton (1871). "The Arawack language of Guiana in its linguistic and ethnological relations". Philadelphia, McCalla & Stavely. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Rouse 1992.

- Reid, Basil (1994). "Tainos not Arawaks: The Indigenous Peoples of Jamaica and the Greater Antilles". Caribbean Geography. 5 (1).

- Rouse 1992, p. 7.

- Rouse, pp. 30–48.

- Martínez-Cruzado, JC; Toro-Labrador, G; Ho-Fung, V; et al. (Aug 2001). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals substantial Native American ancestry in Puerto Rico". Hum. Biol. 73 (4): 491–511. doi:10.1353/hub.2001.0056. PMID 11512677. S2CID 29125467.

- Lorena Madrigal, Madrigal (2006). Human biology of Afro-Caribbean populations. Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-521-81931-2.

- Rouse, p. 16.

- Young, Susan (October 17, 2011). "Rebuilding the genome of a hidden ethnicity". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.592. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- Lawler, Andrew (December 23, 2020). "Invaders nearly wiped out Caribbean's first people long before Spanish came, DNA reveals". National Geographic.

- "Caciques, nobles and their regalia". elmuseo.org. Archived from the original on 2006-10-09. Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- Pané, Ramón. "26". Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios (Siglo XVI) (in Spanish). Wikisource. p. 48. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

...suelen tener dos o tres, y los principales, hasta diez, quince y veinte.

- "Columbus, Ramon Pane, and the beginnings of American anthropology by Bourne, Edward Gaylord, 1860-1908. [from old catalog]". Internet Archive. January 14, 2022. p. 31. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Beding, Silvio, ed. (1002). The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia (ebook ed.). Palgrave MacMillan. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-349-12573-9. Archived from the original on 2017-04-12. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Rouse, p. 15.

- Alegría, "Tainos" p. 346.

- Alegría (1951), p.348.

- "Taino Symbol Meanings". Tainoage.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- "Caribbean Archaeology And Taino Survival". ufdc.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- "Taino Culture". Powhatan Museum's Home Page. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- "TAÍNOS: ARTE Y SOCIEDAD". Issuu (in Spanish). May 15, 1912. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- Cayetano Coll y Toste (author). Prehistoria de Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Tipografía Boletín Mercantil. 1907. p.298. (Reprinted by Editorial El Nuevo Mundo. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2011. ISBN 9781463539283. The Puerto Rico caciques map illustration was also reprinted by the United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, in 1948, in the Handbook of South American Indians: The Circum-Caribbean Tribes, Julian H. Steward, ed., volume 4, for the Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, for their Bulletin 143.)

- Jimenez de Wagenheim, Olga (1998). Puerto Rico: an interpretive history from pre-columbian times to 1900. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 1558761225. OCLC 1025952187.

- "El desarrollo del cacicazgo en las sociedades tardías de Puerto Rico -". enciclopediapr.org. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- Wagenheim, Olga Jiménez de (1998). Puerto Rico : an interpretive history from pre-Columbian times to 1900. Princeton, N.J.: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 1558761217. OCLC 37457914.

- Bigelow, Bill; Peterson, Bob (1998). Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years. Rethinking Schools. ISBN 9780942961201.

- Jimenez de Wagenheim, Olga (1998). Puerto Rico: an interpretive history from pre-Columbian times to 1900. Markus Wiener Publishers. pp. 12–13. ISBN 1558761225. OCLC 1025952187.

- Jimenez de Wagenheim, Olga (1998). Puerto Rico: an interpretive history from pre-columbian times to 1900. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 13. ISBN 1558761225. OCLC 1025952187.

- "Bulletin : Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology". Internet Archive. 23 October 1901. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Reniel (2019-02-25), "Current Perspectives in the Precolonial Archaeology of Puerto Rico", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.620, ISBN 9780199366439

- "Indios Tainos". www.proyectosalonhogar.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-14. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- Jimenez de Wagenheim, Olga (1998). Puerto Rico: an interpretive history from pre-columbian times to 1900. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 1558761225. OCLC 1025952187.

- Rouse, p. 13.

- Francine Jacobs (1992). The Tainos: The People who Welcomed Columbus. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-399-22116-3.

- Rouse, p.12.

- Duke, Guy S. "Continuity, Cultural Dynamics, and Alcohol: The Reinterpretation of Identity through Chicha in the Andes". Identity Crisis: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Identity. Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- Rouse, p. 121.

- Robiu-Lamarche, Sebastián (2006). Mitología y religión de los taínos. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Edit. Punto y Coma. pp. 69, 84. ISBN 0-9746236-4-4.

- Rouse, p. 119.

- Rouse, pp. 13, 118.

- Barreiro, José. "The Idol of Patana: The Troubled History of the Taíno Deity of Boinayel". NMAI Magazine. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Rouse, p. 118.

- Rouse, p. 14.

- Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of Paradise, p. 100, ISBN 0-333-57479-6

- Allen, John Logan (1997). North American Exploration: A New World Disclosed. Volume: 1. University of Nebraska Press. p. 13.

- Kirkpatrick Sale, "The Conquest of Paradise", p. 155, ISBN 0-333-57479-6

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 143. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 132. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 199. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Medina, P.M.A. (2017). "CARTAS de Pedro de Córdoba y de la Comunidad Dominica, algunas refrendadas por los Franciscanos". Guaraguao. El Centro de Estudios y Cooperación para América Latina (CECAL). 21 (54): 155–207. ISSN 1137-2354. JSTOR 44871987. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- Saunders, Nicholas J. Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archeology and Traditional Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005. Web.

- Figueredo, D. H. (2008). A Brief History of the Caribbean. Infobase Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1438108315.

- Deagan, Kathleen A. (2008). Columbus's Outpost Among the Taínos: Spain and America at La Isabela, 1493-1498. Yale University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0300133899.

- Dale, Corrine H., and J. H. E. Paine. Women on the Edge: Ethnicity and Gender in Short Stories by American Women. New York: Garland Pub., 1999. Web.

- Taylor, Patrick, and Frederick I. Case. The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions Volume 1: A-L; Volume 2: M-Z. Baltimore: U of Illinois, 2015. Web. Chapter title Taínos.

- Deagan, Kathleen (2004). "Reconsidering Taino Social Dynamics after Spanish Conquest: Gender and Class in Culture Contact Studies". American Antiquity. 69 (4): 597–626. doi:10.2307/4128440. JSTOR 4128440. S2CID 143836481.

- Sloan, Kathryn A. Women's Roles in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2011. Web.

- Fernandes, Daniel M.; Sirak, Kendra A.; Ringbauer, Harald; Sedig, Jakob; Rohland, Nadin; Cheronet, Olivia; Mah, Matthew; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Culleton, Brendan J.; Adamski, Nicole (February 2021). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844): 103–110. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..103F. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

- Reich, David; Patterson, Orlando (2020-12-23). "Opinion | Ancient DNA Is Changing How We Think About the Caribbean". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- Fernandes, Daniel M.; Sirak, Kendra A.; Ringbauer, Harald; Sedig, Jakob; Rohland, Nadin; Cheronet, Olivia; Mah, Matthew; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Culleton, Brendan J.; Adamski, Nicole (2020-12-23). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844): 103–110. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

- "Endless War of Domination". Student-Employee Assistance Program Against Chemical Dependency. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Lawler, Andrew (December 23, 2020). "Invaders nearly wiped out Caribbean's first people long before Spanish came, DNA reveals". National Geographic.

- Karen Anderson Córdova (1990). Hispaniola and Puerto Rico: Indian Acculturation and Heterogeneity, 1492–1550 (PhD dissertation). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 112. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 182. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 111. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0195085570.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 143. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- David M. Traboulay (1994). Columbus and Las Casas: the conquest and Christianization of America, 1492–1566. p. 44. ISBN 9780819196422. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Diaz Soler, Luis Manuel (1950). Historia De La Esclavitud Negra en Puerto Rico (Thesis). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- "A Brief History of Dominican Republic". SpainExchange Country Guide.

- "La tragédie des Taïnos", in L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 16.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 108. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 160. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Arthur C. Aufderheide; Conrado Rodríguez-Martín; Odin Langsjoen (1998). The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Watts, Sheldon (2003). Disease and medicine in world history. Routledge. pp. 86, 91. ISBN 978-0-415-27816-4. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Schimmer, Russell. "Puerto Rico". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. Archived from the original on 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- Raudzens, George (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-391-04206-3. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Treuer, David (May 13, 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0547640983. Archived from the original on 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- Agorsah, E. Kofi, "Archaeology of Maroon Settlements in Jamaica", Maroon Heritage: Archaeological, Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives, ed. E. Kofi Agorsah (Kingston: University of the West Indies Canoe Press, 1994), pp. 180–1.

- "What Became of the Taíno?".

- Guitar 2000.

- Baker, Christopher (6 February 2019). "Cuba's Taino people: a flourishing culture, believed extinct". BBC Travel. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Barreiro, Jose (September 1989). "Indians in Cuba". Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine.

- "American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010 (CPH-T-6)". Census.gov. Census bureau. 2010. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- L. Guitar; P. Ferbel-Azcarate; J. Esteves (2006). "Ocama-Daca Taíno". In Maximilian Christian Forte (ed.). Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean: Amerindian Survival and Revival. Peter Lang. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8204-7488-5.

- Cave, Damien (December 2, 2008). "Puerto Rico pageant celebrates a vanished native culture". The New York Times.

- Martínez-San Miguel, Yolanda (Spring 2011). "Taino Warriors?: Strategies for Recovering Indigenous Voices in Colonial and Contemporary Hispanic Caribbean Discourses" (PDF). Centro Journal. 13: 211.

- Kirk, Tom (19 February 2018). "Study identifies traces of indigenous 'Taíno' in present-day Caribbean populations". EurekaAlert!. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Schroeder, Hannes; Sikora, Martin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Cassidy, Lara M.; Maisano Delser, Pierpaolo; Sandoval Velasco, Marcela; Schraiber, Joshua G.; Rasmussen, Simon; Homburger, Julian R.; Ávila-Arcos, María C.; Allentoft, Morten E. (2018-02-20). "Origins and genetic legacies of the Caribbean Taino". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (10): 2341–2346. doi:10.1073/pnas.1716839115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5877975. PMID 29463742.

- Baracutei Estevez, Jorge (14 October 2019). "Meet the survivors of a 'paper genocide'". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Haslip-Viera, Gabriel (2014). Race, Identity and Indigenous Politics: Puerto Rican Neo-Taínos in the Diaspora and the Island. Latino Studies Press. pp. 111–117.

- Vilar, Miguel G.; et al. (July 2014). "Genetic diversity in Puerto Rico and its implications for the peopling of the island and the Caribbean". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 155 (3): 352–68. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22569. PMID 25043798.

- Poole, Robert M. (October 2011). "What Became of the Taíno?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Curet, Antonio L. (Spring 2015). "Indigenous Revival, Indigeneity, and the Jíbaro in Borikén". Centro Journal. 27: 206–247.

- Schroeder, Hannes; Sikora, Martin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Cassidy, Lara M.; Delser, Pierpaolo Maisano; Velasco, Marcela Sandoval; Schraiber, Joshua G.; Rasmussen, Simon; Homburger, Julian R.; Ávila-Arcos, María C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Renaud, Gabriel; Gómez-Carballa, Alberto; Laffoon, Jason E.; Hopkins, Rachel J. A.; Higham, Thomas F. G.; Carr, Robert S.; Schaffer, William C.; Day, Jane S.; Hoogland, Menno; Salas, Antonio; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Nielsen, Rasmus; Bradley, Daniel G.; Hofman, Corinne L.; Willerslev, Eske (March 6, 2018). "Origins and genetic legacies of the Caribbean Taino". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (10): 2341–2346. doi:10.1073/pnas.1716839115. PMC 5877975. PMID 29463742.

- "Genes of 'extinct' Caribbean islanders found in living people". Science | AAAS. February 19, 2018.

- Estevez, Jorge Baracutei (August 30, 2017). "CARIBBEAN TAINO AND GUYANA INDIGENOUS PEOPLES CACIQUE CROWN A SYMBOL OF BROTHERHOOD - CELEBRATING OUR INDIGENOUS HERITAGE THE ART OF FEATHER WORK CACHUCHABANA FEATHER HEADDRESSES OF THE TAINO PEOPLES" (PDF). Guyana Folk & Culture. US: Guyana Cultural Association of New York Inc.on-line Magazine. pp. 6–7. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

Cited sources

- Guitar, Lynne (2000). "Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-Afro-European People and Culture on Hispaniola". Kacike. Caribbean Amerindian Centrelink. 1 (1): 1–17.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05696-6.

Further reading

- Harrington, Mark Raymond (1921). Cuba Before Columbus. Cuba Before Columbus. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Abbot, Elizabeth (2010). Sugar: A Bitterweet History. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59020-772-7.

- Chrisp, P. (2006). DK Discoveries: Christopher Columbus. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7566-8616-1.

- Ricardo Alegría (April 1951). "The Ball Game Played by the Aborigines of the Antilles". American Antiquity. 16 (4): 348–352. doi:10.2307/276984. JSTOR 276984. S2CID 164059254.

- Accilien, Cécile; Adams, Jessica; Méléance, Elmide (2006). Revolutionary Freedoms: A History of Survival, Strength and Imagination in Haiti. Paintings by Ulrick Jean-Pierre. Educa Vision. ISBN 978-1-58432-293-1.

- Léger, Jacques Nicolas (1907). Haiti, Her History and Her Detractors. Neale Publishing Company. wikisource

- Guitar, Lynne; Ferbel-Azcarate, Pedro; Estevez, Jorge (2006). "Ocama-Daca Taíno (Hear Me, I Am Taíno): Taíno Survival on Hispaniola, Focusing on the Dominican Republic". In Forte, Maximilian C. (ed.). Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean: Amerindian Survival and Revival. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-0820474885.

- DeRLAS. "Some important research contributions of Genetics to the study of Population History and Anthropology in Puerto Rico". Newark, Delaware: Delaware Review of Latin American Studies. August 15, 2000.

- "The Role of Cohoba in Taíno Shamanism", Constantino M. Torres in Eleusis No. 1 (1998)

- "Shamanic Inebriants in South American Archaeology: Recent Investigations" Constantino M. Torres in Eleusis No. 5 (2001)

- Tinker, Tink; Freeland, Mark (2008). "Thief, Slave Trader, Murderer: Christopher Columbus and Caribbean Population Decline". Wíčazo Ša Review. 23 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1353/wic.2008.0002. S2CID 159481939.

- Guitar, Lynne. "Documenting the Myth of Taíno Extinction". Kacike.

- The art heritage of Puerto Rico, pre-Columbian to present. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and El Museo del Barrio. 1973. (Chapter 1: "The Art of the Taino Indians of Puerto Rico")

- Dutchen, Stephanie (December 23, 2020). "Island investigations". The Harvard Gazette. Harvard University.

External links

- United Confederation of Taíno People (UCTP) / Confederación Unida de el Pueblo Taíno (CUPT)

- Taíno Diccionary, A dictionary of words of the indigenous peoples of caribbean from the encyclopedia "Clásicos de Puerto Rico, second edition, publisher, Ediciones Latinoamericanas. S.A., 1972" compiled by Puerto Rican historian Dr. Cayetano Coll y Toste of the "Real Academia de la Historia".

- 2011 Smithsonian article on Taíno culture remnant in the Dominican Republic

- USVI Taino Chief Seeks Members. Amy H. Roberts. The St. Thomas Source. St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. 6 April 2022. Accessed 5 May 2022.] Archived.