Tintin and the Picaros

Tintin and the Picaros (French: Tintin et les Picaros) is the twenty-third volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The final instalment in the series to be completed by Hergé, it was serialized in Tintin magazine from September 1975 to April 1976 before being published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1976. The narrative follows the young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy and his friends Captain Haddock and Professor Calculus as they travel to the (fictional) South American nation of San Theodoros to rescue their friend Bianca Castafiore, who has been imprisoned by the government of General Tapioca. Once there, they become involved in the anti-government revolutionary activities of Tintin's old friend General Alcazar.

| Tintin and the Picaros (Tintin et les Picaros) | |

|---|---|

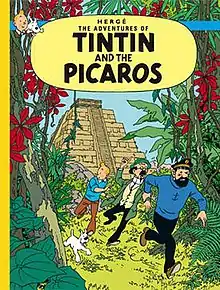

Cover of the English-language edition | |

| Date | 1976 |

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Tintin magazine |

| Date of publication | 16 September 1975 – 13 April 1976 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Methuen |

| Date | 1976 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Flight 714 to Sydney (1968) |

| Followed by | Tintin and Alph-Art (1986) |

Hergé began work on Tintin and the Picaros eight years after completing the previous volume in the series, Flight 714 to Sydney, creating it with the aid of his team of artists at Studios Hergé. The setting and plot was inspired by Hergé's interest in Latin American revolutionaries, particularly those active in the Cuban Revolution. The book reflected changes to the appearance and behaviour of several key characters in the series; influenced by his design in the animated films Tintin and the Temple of the Sun and Tintin and the Lake of Sharks, Tintin is depicted wearing bell-bottoms instead of his trademark plus fours.

The volume was published to a poor reception and has continued to receive negative reviews from later commentators on Hergé's work. Early criticism of the story focused on what was seen as its pessimistic portrayal of its political themes, while later reviews concentrated on the poor characterisation and lack of energy. Hergé continued The Adventures of Tintin with Tintin and Alph-Art, a story that he never completed, and the series as a whole became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. The story was adapted for an episode of the 1991 animated series The Adventures of Tintin by Ellipse and Nelvana.

Synopsis

Tintin and his dog Snowy visit their friends Captain Haddock and Professor Calculus at Marlinspike Hall. There, they learn that Bianca Castafiore, her maid Irma, pianist Igor Wagner and the detectives Thomson and Thompson have been imprisoned in San Theodoros for allegedly attempting to overthrow the military government of General Tapioca. Tapioca's government have further alleged that the plot was masterminded by Tintin, Haddock, and Calculus themselves.

Tapioca invites the trio to visit San Theodoros, promising them safe passage, but Tintin deems it to be a trap, leaving Haddock and Calculus to go alone. Once there, the Captain and Professor are taken to a rural villa, where they are closely monitored by the security services.[1] Tintin joins his friends a few days later, where he points out to Haddock and Calculus that their villa is bugged. He recognises one of the staff as Pablo, a man who had saved his life in The Broken Ear. From Pablo, Tintin learns that the entire scenario is a plot organised by Colonel Sponsz, a figure in the Bordurian military who is assisting Tapioca's government in order to gain revenge against Tintin for the events of The Calculus Affair.[2]

With Pablo's assistance, Tintin, Snowy, Haddock, and Calculus escape from their guards on a pyramid and seek refuge with General Alcazar and his small band of anti-Tapioca guerrillas, the Picaros, who are hiding in the South American jungle. After realising that Pablo is a double agent working for Tapioca, they escape an assault by a field gun and then shelter for a time with the Arumbaya, an indigenous community who live within the forest. Here, Tintin is reunited with his old acquaintance, the eccentric explorer Ridgewell, who is living with the Arumbaya. Leaving the Arumbaya settlement, they eventually arrive at the Picaros' encampment, where they meet Alcazar's wife, Peggy.

However, Tapioca has been air-dropping loads of whiskey into the jungle to intoxicate the Picaros. Alcazar realises that the Picaros will fail to launch a successful coup against Tapioca while they remain drunkards, and to combat this problem, Calculus provides them with tablets which render the taste of alcohol disgusting. Soon afterward, Jolyon Wagg and his troupe of carnival performers, the "Jolly Follies", arrive at the camp, having lost their way to Tapiocapolis where they mean to take part in the carnival. At Tintin's suggestion, the Picaros disguise themselves in the Follies' costumes and enter Tapiocapolis during the carnival. There, they storm the presidential palace and seize control; Thomson and Thompson are rescued from a firing squad while Castafiore and her assistants are released from prison. Afterward, Alcazar becomes president, with Tapioca and Sponsz being exiled from the country as punishment for their crimes.[5]

History

Background

"It's the atmosphere that has inspired me: everything happening in South America. Brazil and torture, the Tupamaros, Fidel Castro, Che. Without even saying where my sympathies lie ... I obviously sympathize with Che Guevara, but at the same time I know terrible things are happening in Cuba. Nothing is black or white!"

Hergé[6]

Hergé began Tintin and the Picaros eight years after completing his previous Adventure of Tintin, Flight 714 to Sydney.[7] It would prove to be the only book that he completed during the final fifteen years of his life.[8] He decided to develop the story around a group of Latin American revolutionaries, having had this idea since the early 1960s, prior to embarking on The Castafiore Emerald.[9] In particular, he had been inspired by the activities of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement when they were launching a guerrilla war from the Sierra Maestra during the Cuban Revolution against President Fulgencio Batista. Specifically, Hergé was interested in Castro's statement that he would not cut his beard until the revolution had succeeded.[10] Adopting this idea of the revolutionaries' facial hair, he initially planned to refer to Alcazar's group as the Bigotudos, a reference to the Spanish word bigotudos, meaning "moustached".[10] As such, the story's initial working title was Tintin et los Bigotudos, before Hergé later settled on Tintin et les Picaros.[11]

Hergé's depiction of a band of Latin American revolutionaries was also influenced by the French leftist activist Régis Debray's accounts of his time spent fighting in the Bolivian Andes alongside the Argentine Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Che Guevara.[12] Hergé's depiction of Bordurian support for Tapioca's government was a reference to the Soviet Union's support for various Latin American regimes, most notably that of Castro's Cuba,[13] with San Theodoros being depicted as having been governed under the ideological system of Borduria's political leader, Kurvi-Tasch.[14] Similarly, Hergé included a reference to Alcazar being backed by the International Banana Company in order to reflect the influence of Western multinational corporations in Latin America.[14]

Hergé's depiction of the city of Tapiocapolis was visually based on the city of Belo Horizonte in Brazil.[15] His depiction of a public sculpture in the city was inspired by the work of sculptor Marcel Arnould,[15] while the paintings that he designed for the Tapiocapolis hotel in which Tintin and Haddock stay are based on the work of Serge Poliakoff.[15]

Hergé incorporated many characters from previous Adventures into Tintin and the Picaros; these include Pablo, Ridgewell, and the Arumbaya tribe from The Broken Ear, as well as Colonel Sponz from The Calculus Affair.[16] The character of General Tapioca, who had been mentioned in previous Adventures but never depicted, was also introduced.[17] Hergé also introduced a new character, Peggy Alcazar, whom he had based upon the American secretary to a Ku Klux Klan spokesman whom Hergé observed in a television documentary.[18] In his preparatory notes for the story, Hergé had considered introducing Peggy as the daughter of arms dealer Basil Bazaroff – the satirical depiction of the old times real-life arms dealer Basil Zaharoff, who had appeared in The Broken Ear.[19] He also introduced the Jolly Follies into the story, a group who were based on three separate touring party groups that Hergé had encountered.[20] He had initially considered a number of alternative names for the troupe, including the Turlupins, Turlurans, and Boutentrins.[21]

For this Adventure, Hergé decided to update his depiction of Tintin's clothes, having been influenced in doing so by the depiction of the character in the 1969 animated film Tintin and the Temple of the Sun and its 1972 sequel Tintin and the Lake of Sharks. As such, in Tintin and the Picaros, the young reporter is depicted wearing a sheepskin flight jacket and open-faced helmet emblazoned with a CND symbol, while he also wears new bell-bottoms rather than the plus-fours that he had worn in previous instalments.[22] Later commenting on the inclusion of the CND peace symbol, Hergé stated that for Tintin, "That's normal. Tintin is a pacifist, he was always anti-war."[19] Hergé also changed the behaviour of several characters in the story, for instance by depicting Tintin practising yoga and Nestor the butler both eavesdropping and drinking Haddock's whisky.[23] Another new development that Hergé added to the story was Haddock's first name, Archibald.[15]

Hergé's depiction of the San Theodoran carnival was drawn largely from images of the Nice Carnival.[15] Among the revelers, he included those dressed in the costumes of various different cartoon and film characters, such as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Asterix, Snoopy, Groucho Marx, and Zorro.[24] Hergé also included a band known as the Coconuts into the carnival scene; these were not developed by Hergé himself but were rather the creations of his friend and colleague Bob de Moor, who had devised them for his own comic series, Barelli.[15] The street that they were marching down, Calle 22 de Mayo, was named after Hergé's own birthday, 22 May.[25]

Publication

Tintin et les Picaros began serialisation in both Belgium and France in Tintin-l'Hebdoptmiste magazine in September 1975.[26] It was then published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1976.[26] For this publication, a page was removed from the story so that it would fit the standard 62-page book format.[27] The page in question was located between pages 22 and 23 of the published book, and featured Sponz attempting to smash a glass, but accidentally breaking a statue of Bordurian political leader Kurvi-Tasch instead.[27] A launch party was held at the Hilton Hotel in Brussels.[28]

Upon publication, it proved a commercial success with one and a half million copies soon sold.[29] It was nevertheless critically panned at the time.[30] Various contemporary critics condemned what they deemed to be the political apathy of the story; as they pointed out, Hergé's depiction of regime change in San Theodoros does not bring about any improvement for the nation's populace, with the critics from Belgium's Hebdo 76 and France's Révolution thereby characterising it as a reactionary work.[31] On this front, Tintin in the Picaros was defended by the French philosopher Michel Serres, who stated that "The criticism that has been leveled at Picaros is astonishing. There is no talk of revolution; the people are in the favelas, and they stay there. It is only a government overthrow. A general, aided by several assassins, takes the place of a general protected by his own bodyguards. This is why it is only repetition; it is just a movement reduced to this. And that is the chloroform; it is what we see everywhere. You can give as many modern examples of the Alcazar-Tapioca rivalry, or of double identities, as you want."[32] In June 1977, Hergé travelled to Britain for Methuen's launch of the story's English translation, where he spent two weeks giving interviews and attending book signings.[33]

Critical analysis

Harry Thompson felt that Hergé's use of various characters from earlier stories lent Tintin and the Picaros "the air of a finale".[8] Hergé biographer Benoît Peeters felt that in this story, the characters were "more passive than in the earlier adventures, submitting to events more than setting them off", with this being particularly evident for the character of Tintin.[34] Michael Farr stated that "Tintin has changed", as is evidenced by the change in his clothing, however he felt that "such image modernising only succeeds in dating the adventure", adding that "to alter Tintin's appearance at the end of his career was not only superfluous but a mistake".[19]

Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier stated that in this story, Alcazar was "a deflated version of what he used to be", noting that by the end of the story he had become "a prisoner in his own palace. A sad, yet somehow appropriate, ending".[26] Farr suggested that the changes to the characters represented "an element of dismantling of the characters and their traits", something that he believed had also been present in the previous two adventures, Flight 714 to Sydney and The Castafiore Emerald.[35] In his psychoanalytical study of The Adventures of Tintin, the literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès expressed the view that, as with The Red Sea Sharks, Tintin and the Picaros served as "a kind of retrospective" due to the return of various characters.[36] He also suggested that the carnival revelers in San Theodoros evoked the figures from the previous stories: "Scots, Africans, Chinese, Indians, cowboys, bullfighters, and, of course, the inevitable parrot".[37] The Lofficiers saw the adventure as a partial sequel to The Broken Ear, which was also set in San Theodoros and which contained many of the same characters.[38]

Thompson considered Tintin and the Picaros to be "Hergé's most overtly political book for many years" but felt that, unlike Hergé's earlier political works, "no campaigning element" is present.[20] Peeters agreed, noting that Tintin in the Picaros is "a far cry from the denunciation of a political system found in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, and also from the almost militantly anti-Japanese tone of The Blue Lotus."[39] He thought that in this story, "a sense of disillusionment has taken over", for it is "quite clear that [Alcazar's seizure of power] is no real revolution but a palace coup".[39] Farr noted that this story showed that "the idealist of 1930s is by 1970s a realist", in that while "totalitarianism ... and the manipulation of the multinational concerns ... are still condemned ... Tintin accepts he can do little to change them".[40]

The Lofficiers were ultimately highly critical of Tintin and the Picaros, awarding it two out of five, and describing it as "just sad".[41] Specifically, they felt that the "undefinable magic of the Hergé line" was "sometimes missing" from the story, believing that this had been caused by too much of the work having been turned over to his assistants in the Studios Hergé.[41] Further, they felt that the "characters seem tired: Tintin is totally reactive — even on the book cover, it is Haddock who takes the lead".[41] Thompson echoed similar views, believing that "life has not been breathed into the characters as normal" and that there was "something indefinable absent" from the drawings, "enjoyment, perhaps".[42] He added that while it contained "many fine vignettes", "over all it is a lacklustre story, missing the sparkle of a genuine Tintin adventure".[8] Peeters thought that "the comedy here seems mechanical" and "neither the characters, nor the plot, nor the drawings ring true".[32]

The literary critic Tom McCarthy believed that Tintin and the Picaros reflected a number of themes found throughout The Adventures of Tintin. For instance, he believed that the theme of eavesdropping was exhibited in the scene in which Nestor the butler listens in on Tintin and Haddock's argument.[43] He also expressed the view that Tintin, Haddock, and Calculus' imprisonment in their Los Dopicos hotel reflected the "uneasy host–guest relationship" theme.[44]

McCarthy believed that the inclusion of the CND symbol on Tintin's motorcycle helmet at the start of the story was a sign that Hergé's left-wing tendency had won out over the right-wing perspectives which dominated his early work.[45] He also placed emphasis on the fact that no executions were held during Alcazar's revolution, adding that "its blood ... will fail it: it will be anaemic", thus being a reference to Hergé's anaemia.[46] Further, he suggested that the loss of the ability to drink alcohol served as a symbolic castration.[47]

Apostolidès expressed the view that many of the characters in Tintin and the Picaros could be divided into pairs.[48] He considered Calculus and Alcazar to be one such pair, noting that they are "both masters of power and control, the former in science and the latter in politics".[49] He also placed Castafiore and Peggy together as a pair, noting that they each embody "love, both maternal and romantic".[49] Haddock and Wagg were also paired together, both being "driven to succeed, but the former is happy with playing out his success in private life, whereas the latter tries to aggrandize himself everywhere".[50] Finally, he paired together Ridgewell and Tintin, noting that while in The Broken Ear they had a father-son style relationship, at this point they have become equals.[50]

Adaptations

In 1991, a collaboration between the French studio Ellipse and the Canadian animation company Nelvana adapted 21 of the stories into a series of episodes, each 42 minutes long. Tintin and the Picaros was one of the stories included in the television series. Directed by Stéphane Bernasconi, the series has been praised for being "generally faithful", with compositions having been actually directly taken from the panels in the original comic book.[51]

References

Footnotes

- Hergé 1976, pp. 1–21.

- Hergé 1976, pp. 21–25.

- "Les autos de Tintin, liste complète".

- "DAF SB 1602 Jonckheere". 23 July 2017.

- Hergé 1976, pp. 25–62.

- Peeters 2012, p. 323.

- Peeters 1989, p. 125; Farr 2001, p. 190; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 82.

- Thompson 1991, p. 195.

- Farr 2001, p. 189; Peeters 2012, p. 323.

- Farr 2001, p. 189; Goddin 2011, p. 132.

- Farr 2001, p. 189.

- Thompson 1991, p. 196; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Farr 2001, pp. 193, 195.

- Farr 2001, p. 195.

- Farr 2001, p. 197.

- Peeters 1989, p. 127; Farr 2001, p. 190; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Peeters 1989, p. 127; Farr 2001, p. 190.

- Peeters 1989, p. 126; Thompson 1991, p. 199; Farr 2001, p. 190; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Farr 2001, p. 190.

- Thompson 1991, p. 196.

- Goddin 2011, p. 168.

- Peeters 1989, p. 126; Thompson 1991, p. 194; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Thompson 1991, p. 194.

- Farr 2001, p. 197; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Thompson 1991, p. 196; Farr 2001, p. 197.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 82.

- Thompson 1991, p. 199; Farr 2001, p. 195.

- Goddin 2011, p. 189.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 82; Peeters 2012, p. 325.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 82; Peeters 2012, pp. 323–324.

- Peeters 2012, pp. 324–345.

- Peeters 2012, p. 325.

- Goddin 2011, p. 192.

- Peeters 1989, p. 126.

- Farr 2001, p. 192.

- Apostolidès 2010, p. 260.

- Apostolidès 2010, p. 273.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 83.

- Peeters 1989, p. 127.

- Farr 2001, p. 193.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 84.

- Thompson 1991, p. 199.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 26.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 136.

- McCarthy 2006, pp. 38–39.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 59.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 115.

- Apostolidès 2010, pp. 260–261.

- Apostolidès 2010, p. 261.

- Apostolidès 2010, p. 262.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 90.

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Farr, Michael (2007). Tintin & Co. London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4052-3264-7.

- Goddin, Philippe (2011). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume 3: 1950–1983. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-763-1.

- Hergé (1976). Tintin and the Picaros. Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner (translators). London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4420-4708-2.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

External links

- Tintin and the Picaros at the Official Tintin Website

- Tintin and the Picaros at Tintinologist.org

.jpg.webp)