Tintin in the Congo

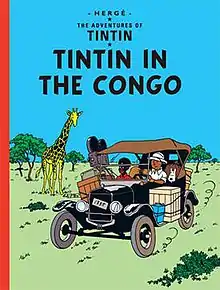

Tintin in the Congo (French: Tintin au Congo; French pronunciation: [tɛ̃tɛ̃ o kɔ̃go]) is the second volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from May 1930 to June 1931 before being published in a collected volume by Éditions de Petit Vingtième in 1931. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who are sent to the Belgian Congo to report on events in the country. Amid various encounters with the native Congolese people and wild animals, Tintin unearths a criminal diamond smuggling operation run by the American gangster Al Capone.

| Tintin in the Congo (Tintin au Congo) | |

|---|---|

Cover of the English edition of the colour version | |

| Date |

|

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Le Petit Vingtième |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Le Petit Vingtième |

| Date of publication | 5 June 1930 – 11 June 1931 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher |

|

| Date |

|

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1930) |

| Followed by | Tintin in America (1932) |

Following on from Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and bolstered by publicity stunts, Tintin in the Congo was a commercial success within Belgium and was also serialised in France. Hergé continued The Adventures of Tintin with Tintin in America in 1932, and the series subsequently became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. In 1946, Hergé re-drew and coloured Tintin in the Congo in his distinctive ligne-claire style for republication by Casterman, with further alterations made at the request of his Scandinavian publisher for a 1975 edition.

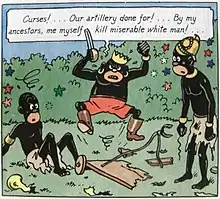

In the late 20th century, Tintin in the Congo became increasingly controversial for both its racist colonial attitude toward Congolese people and for its glorification of big-game hunting. Accordingly, attempts were made in Belgium, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States to either ban the work or restrict its availability to children. Critical reception of the work has been largely negative, with commentators on The Adventures of Tintin describing it as one of Hergé's lesser works.

Synopsis

Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy travel to the Belgian Congo, where a cheering crowd of native Congolese greet them.[1] Tintin hires a native boy, Coco, to assist him in his travels, and soon thereafter Tintin rescues Snowy from a crocodile. A criminal stowaway tries to kill Tintin, but monkeys throw coconuts at the stowaway that knock him unconscious. A monkey kidnaps Snowy, but Tintin saves him by disguising himself as another monkey. That night, the stowaway escapes.[2]

The next morning, Tintin, Snowy, and Coco crash their car into a train, which the reporter fixes and tows to the village of the Babaorum[lower-alpha 1] tribe. He meets the king, who invites him to a hunt the next day. A lion knocks Tintin unconscious, but Snowy rescues him by biting off its tail. Tintin gains the admiration of the natives, making the Babaorum witch-doctor Muganga jealous. With the help of the criminal stowaway, Muganga accuses Tintin of destroying the tribe's sacred idol. The enraged villagers imprison Tintin, but then turn against Muganga when Tintin shows them footage of the witch-doctor and the stowaway conspiring to destroy the idol. Tintin becomes a hero in the village: when he cures a man using quinine, he is hailed as a Boula Matari ("Breaker of rocks")[lower-alpha 2] and a local woman bows down to him, saying, "White man very great! Has good spirits ... White mister is big juju man!"[5] Angered, Muganga starts a war between the Babaorum and their enemies, the M'Hatuvu,[lower-alpha 3] whose king leads an attack on the Babaorum village. Tintin outwits them, and the M'Hatuvu cease hostilities and come to idolise Tintin. Muganga and the stowaway plot to kill Tintin and make it look like a leopard attack, but Tintin survives and saves Muganga from a boa constrictor; Muganga pleads mercy and ends his hostilities.

The stowaway again attempts to kill Tintin, binding him and hanging him from a tree branch over a river to be eaten by crocodiles, but he is rescued by a passing a Catholic missionary, who invites Tintin to go on an elephant hunt. Then, disguised as a missionary, the stowaway captures Tintin again, leaving him tied up in a boat set to go over a waterfall, but the Catholic priest once again saves him. Tintin confronts the stowaway and they fight over a cliff, where the latter is eaten by crocodiles. [6] After reading a letter from the stowaway's pocket, Tintin finds that someone called "A.C." has ordered his elimination. Tintin captures a criminal who tried to rendezvous with the stowaway and learns that "A.C." is none other than the American gangster Al Capone, who is trying to gain control of African diamond production. Tintin and the colonial police arrest the rest of the diamond smuggling gang and after having a few more adventures with different animals, Tintin and Snowy return to Belgium.[7]

History

Background

Georges Remi—best known under the pen name Hergé—was the editor and illustrator of Le Petit Vingtième ("The Little Twentieth"),[8] a children's supplement to Le Vingtième Siècle ("The Twentieth Century"), a staunchly Roman Catholic, conservative Belgian newspaper based in Hergé's native Brussels. Run by the Abbé Norbert Wallez, the paper described itself as a "Catholic Newspaper for Doctrine and Information" and disseminated a far-right, fascist viewpoint.[9] According to Harry Thompson, such political ideas were common in Belgium at the time, and Hergé's milieu was permeated with conservative ideas revolving around "patriotism, Catholicism, strict morality, discipline, and naivety".[10]

"For the Congo as with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the fact was that I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved ... It was 1930. I only knew things about these countries that people said at the time: 'Africans were great big children ... Thank goodness for them that we were there!' Etc. And I portrayed these Africans according to such criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed then in Belgium".

Hergé, talking to Numa Sadoul[11]

In 1929, Hergé began The Adventures of Tintin comic strip for Le Petit Vingtième, a series about the exploits of a fictional Belgian reporter named Tintin. Following the success of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, serialised weekly in Le Petit Vingtième from January 1929 to May 1930, Hergé wanted to send Tintin to the United States. Wallez insisted he write a story set in the Belgian Congo, then a Belgian colony and today the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[12] Belgian children learned about the Congo in school, and Wallez hoped to encourage colonialist and missionary zeal in his readership.[13] He believed that the Belgian colonial administration needed promotion at a time when memories "were still fairly fresh" of the 1928 visit to the colony by the Belgian King Albert and Queen Elisabeth.[14] He also hoped that some of his readers would be inspired to work in the Congo.[15]

Hergé characterised Wallez's instructions in a sarcastic manner, saying Wallez referred to the Congo as "our beautiful colony which has great need of us, tarantara, tarantaraboom".[16] He already had some experience in illustrating Congolese scenes; three years previously, Hergé had provided two illustrations for the newspaper that appeared in an article celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Henry Morton Stanley's expedition to the Congo. In one of these, Hergé depicted a native Congolese bowing before a European, a scene that he repeated in Tintin in the Congo.[17]

As in Land of the Soviets, where Hergé had based his information about the Soviet Union almost entirely on a single source, in Tintin in the Congo he used limited source material to learn about the country and its people. He based the story largely on literature written by missionaries, with the only added element being that of the diamond smugglers, possibly adopted from the "Jungle Jim-type serials".[18] Hergé visited the Colonial Museum of Tervuren, examining their ethnographic collections of Congolese artefacts, including costumes of the Leopard Men.[19] He adopted hunting scenes from André Maurois's novel The Silence of Colonel Bramble, while his animal drawings were inspired by Benjamin Rabier's prints.[17] He also listened to tales of the colony from some of his colleagues who had been there, but disliked their stories, later claiming: "I didn't like the colonists, who came back bragging about their exploits. But I couldn't prevent myself from seeing the Blacks as big children, either".[15]

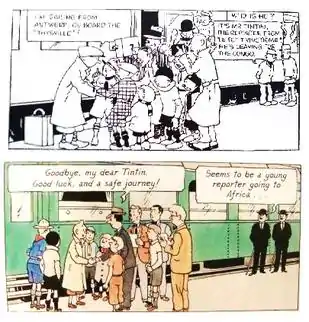

Original publication, 1930–31

Tintin in the Congo was serialised under the French title of Tintin au Congo in Le Petit Vingtième from 5 June 1930 to 11 June 1931; it was syndicated to the French Catholic newspaper Cœurs Vaillants.[20] Drawn in black and white, it followed the same formula employed in Land of the Soviets, remaining "essentially plotless" according to the Hergé specialist Michael Farr, and consisting of largely unrelated events that Hergé improvised each week.[21] Hergé later commented on the process of writing these early adventures, stating: "The Petit Vingtième came out on Wednesday evening, and I often didn't have a clue on Wednesday morning how I was going to get Tintin out of the predicament I had put him in the previous week".[16] The strip's visual style was similar to that of Land of the Soviets.[22] In the first instalment of Tintin in the Congo, Hergé featured Quick and Flupke, two young boys from Brussels whom he had recently introduced in another Le Petit Vingtième comic strip, in the crowd of people saying goodbye to Tintin.[23]

Like Land of the Soviets, Tintin in the Congo was popular in Belgium. On the afternoon of 9 July 1931, Wallez repeated the publicity stunt he had used when Soviets ended by having a young actor, Henry de Doncker, dress up as Tintin in colonial gear and appear in Brussels and then Liège, accompanied by 10 African bearers and an assortment of exotic animals hired from a zoo. Co-organised with the Bon Marché department store, the event attracted 5,000 spectators in Brussels.[24] In 1931, Brussels-based Éditions de Petit Vingtième collected the story together into a single volume, and Casterman published a second edition in 1937.[20] By 1944 the book had been reprinted seven times, and had outsold each of the other seven books in the series.[lower-alpha 4][25] The series' success led Wallez to renegotiate Hergé's contract, giving him a higher salary and the right to work from home.[26]

Second version, 1946

In the 1940s, after Hergé's popularity increased, he redrew many of the original black-and-white Tintin stories in colour using the ligne claire ("clear line")[lower-alpha 5] drawing style he had developed, so that they fitted in visually with the newer Adventures of Tintin that he had produced.[28] Hergé first made some changes in this direction in 1940, when the story was serialised in the Dutch-language Het Laatste Nieuws.[29]

At Casterman's prompting, Tintin in the Congo was subsequently fully re-drawn, and the new version was published in 1946.[28] As a part of this modification, Hergé cut the page length from 110 plates to the standard 62 pages, as suggested by the publisher Casterman. He also made several changes to the story, cutting many of the references to Belgium and colonial rule.[28] For example, in the scene where Tintin teaches Congolese school children about geography, he states in the 1930–31 version: "My dear friends, today I'm going to talk to you about your country: Belgium!" whereas in the 1946 version, he instead gives them a mathematics lesson.[28] Hergé also changed the character of Jimmy MacDuff, the owner of the leopard that attacks Tintin, from a black manager of the Great American Circus into a white "supplier of the biggest zoos in Europe".[28]

In the 1946 colour version, Hergé added a cameo appearance from Thomson and Thompson, the two detectives that he had introduced in the fourth Tintin story, Cigars of the Pharaoh (1932–34), which was chronologically set after the Congolese adventure. Adding them to the first page, Hergé featured them in the backdrop, watching a crowd surrounding Tintin as he boards a train and commenting that it "Seems to be a young reporter going to Africa ..."[14] In the same frame, Hergé inserted depictions of himself and his friend Edgar P. Jacobs (the book's colourist) into the crowd seeing Tintin off.[30]

Later alterations and releases

When Tintin in the Congo was first released by the series' Scandinavian publishers in 1975, they objected to page 56, where Tintin drills a hole into a live rhinoceros, fills it with dynamite, and blows it up. They asked Hergé to replace this page with a less violent scene, which they believed would be more suitable for children. Hergé agreed, as he regretted the scenes of big-game hunting in the work soon after producing it. The altered page involved the rhinoceros running away unharmed after accidentally knocking down and triggering Tintin's gun.[31]

Although publishers worldwide had made it available for many years, English publishers refused to publish Tintin in the Congo because of its perceived racist content. In the late 1980s, Nick Rodwell, then agent of Studios Hergé in the United Kingdom, told reporters of his intention to finally publish it in English and stated his belief that publishing the original 1931 black and white edition would cause less controversy than releasing the 1946 colour version.[30] After more delay, in 1991—sixty years after its original 1931 publication—it was the last of The Adventures of Tintin to see publication in English.[11] The 1946 colour version eventually appeared in English in 2005, published in Britain by Egmont.[32]

Critical analysis

Hergé biographer Pierre Assouline believed that Hergé's drawing became more assured throughout the first version of the story without losing any of its spontaneity.[17] He thought that the story began in "the most inoffensive way", and that throughout the story Tintin was portrayed as a Boy Scout, something he argued reflected Hergé's "moral debt" to Wallez.[17] Biographer Benoît Peeters opined that Tintin in the Congo was "nothing spectacular", with some "incredibly cumbersome" monologues, but he thought the illustrations "a bit more polished" than those in Land of the Soviets.[33] Believing the plot to be "extremely simple", he thought that Tintin's character was like a child manipulating a world populated by toy animals and lead figurines.[26] Michael Farr felt that, unlike the previous Tintin adventure, some sense of a plot emerges at the end of the story with the introduction of the American diamond-smuggling racket.[21] Philippe Goddin thought the work to be "more exciting" than Land of the Soviets and argued that Hergé's depiction of the native Congolese was not mocking but a parody of past European militaries.[34] By contrast, Harry Thompson believed that "Congo is almost a regression from Soviets", in his opinion having no plot or characterisation; he described it as "probably the most childish of all the Tintin books".[35] Simon Kuper of the Financial Times criticised both Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo as the "worst" of the Adventures, opining that they were "poorly drawn" and "largely plot-free".[36]

Farr saw the 1946 colour version as poorer than the black and white original; he said it had lost its "vibrancy" and "atmosphere", and that the new depiction of the Congolese landscape was unconvincing and more like a European zoo than the "parched, dusty expanses of reality".[11] Peeters took a more positive attitude towards the 1946 version, commenting that it contained "aesthetic improvements" and "clarity of composition" because of Hergé's personal development in draughtsmanship, as well as an enhancement in the dialogue, which had become "more lively and fluid".[37]

In his psychoanalytical study of the series, Jean-Marie Apostolidès highlighted that in the Congolese adventure, Tintin represented progress and the Belgian state was depicted as a model for the natives to imitate. In doing so, he argued, they could become more European and thus civilised from the perspective of Belgian society, but that instead they ended up appearing as parodies.[38] Opining that Tintin was imposing his own view of Africa onto the Congolese, Apostolidès remarked that Tintin appeared as a god-figure, with evangelical overtones in the final scene.[39] Literary critic Tom McCarthy concurred that Tintin represented the Belgian state, but also suggested that he acted as a Christian missionary, even being "a kind of god" akin to the character of Kurtz in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899).[40] McCarthy compared the scene where Tintin exposes Muganga as a fraud to that in which the character of Prospero exposes the magician in William Shakespeare's The Tempest.[40]

Criticism

Racism

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, several campaigners and writers characterised Tintin in the Congo as racist due to its portrayal of the Congolese as infantile and stupid.[41] According to McCarthy, Hergé depicted the Congolese as "good at heart but backwards and lazy, in need of European mastery".[42] There had been no such controversy when originally published,[43] because it was only following the decolonisation of Africa, which occurred during the 1950s and 1960s, that Western attitudes towards indigenous Africans shifted.[11] Harry Thompson argued that Tintin in the Congo must be viewed in the context of European society in the 1930s and 1940s, and that Hergé had not written the book to be "deliberately racist". Thompson argued that the story reflected the average Belgian view of Congolese people at the time, one that was more "patronising" than malevolent.[35] Apostolidès supported this idea,[44] as did Peeters, who asserted that "Hergé was no more racist than the next man".[15] After meeting Hergé in the 1980s, Farr commented, "You couldn't have met someone who was more open and less racist."[45]

Contrastingly, Assouline stated that in 1930s Belgium, Hergé would have had access to literature by the likes of André Gide and Albert Londres that was critical of the colonial regime. Assouline claimed that Hergé instead chose not to read such reports because they conflicted with the views of his conservative milieu.[46] Laurence Grove—President of the International Bande Dessinée Society and an academic at the University of Glasgow—concurred, remarking that Hergé adhered to prevailing societal trends in his work, and that "[w]hen it was fashionable to be a colonial racist, that's what he was".[45] Comic book historian Mark McKinney noted that other Franco-Belgian comic artists of the same period had chosen to depict the native Africans in a more favourable light, citing the examples of Jijé's 1939 work Blondin et Cirage (Blondy and Shoe-Black), in which the protagonists are adopted brothers, one white, the other black, and Tif et Tondu, which was serialised in Spirou from 1939 to 1940 and in which the Congolese aid the Belgians against their American antagonists.[47]

Farr and McCarthy stated that Tintin in the Congo was the most popular Tintin adventure in Francophone Africa.[48] According to Thompson, the book remained hugely popular in the Congo even after the country achieved independence in 1960.[49] Nevertheless, government figures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have criticised the book. In 2004, after the Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs Karel De Gucht described President Joseph Kabila's provisional DRC government as incompetent, Congolese Information Minister Henri Mova Sakanyi accused him of "racism and nostalgia for colonialism", remarking that it was like "Tintin in the Congo all over again".[50] The South African comics writer Anton Kannemeyer has parodied the perceived racist nature of the book to highlight what he sees as the continuing racist undertones of South African society. In his Pappa in Afrika (2010), a satire of Tintin in the Congo, he portrays Tintin as an Afrikaner with racist views of indigenous Africans.[51]

Attempts to ban or restrict access to the book

In August 2007, Congolese student Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo filed a complaint in Brussels, claiming that Tintin in the Congo was an insult to the Congolese people that should be banned. Public prosecutors initiated a criminal case although the matter was transferred to a civil court in April 2010.[52] Mondondo called the comic "racist and xenophobic," while his lawyers argued that it amounted to "a justification of colonisation and of white supremacy".[52] Alain Berenboom, lawyer for both Moulinsart, the company which controls Hergé's estate, and Casterman, the book's publisher, argued that the cartoonist's depiction of the Congolese "wasn't racism but kind paternalism". Berenboom said that banning it would set a dangerous precedent for the availability of literature by other historical authors, such as Charles Dickens or Jules Verne, which also contain stereotypes of non-white ethnicities.[52] In February 2012 the court ruled that the book would not be banned, deciding that it was "clear that neither the story, nor the fact that it has been put on sale, has a goal to ... create an intimidating, hostile, degrading, or humiliating environment", and that it therefore did not break Belgian law.[52] Belgium's Centre for Equal Opportunities warned against "over-reaction and hyper political correctness".[53]

In July 2007, British human rights lawyer David Enright complained to the United Kingdom's Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) that the book was sold in the children's section of Borders bookshop. The CRE called on bookshops to remove the comic; responding that it was committed to letting its "customers make the choice", Borders moved the book to an area reserved for adult graphic novels. UK bookseller Waterstone's followed suit.[54] Another British retailer, WHSmith, said that the book was sold on its website, but with a label that recommended it for readers aged 16 and over.[55] The CRE's attempt to ban the book was criticised by Conservative Party politician Ann Widdecombe, who remarked that the organisation had more important things to do than regulate the availability of historical children's books.[56] The media controversy increased interest in the book, and Borders reported that its sales of Tintin in the Congo had been boosted 4,000%, while it also rose to eighth on the Amazon.com bestseller list.[57] Publisher Egmont UK also responded to racism concerns by placing a protective band around the book with a warning about its content and writing an introduction describing its historical context.[54]

Tintin in the Congo also came under criticism in the United States; in October 2007, in response to a complaint by a patron, the Brooklyn Public Library in New York City placed the graphic novel in a locked back room, only permitting access by appointment.[58] Tintin in the Congo became part of a drawn-out media debate in Sweden after national newspaper Dagens Nyheter reported on the book's removal from a children's library in Kulturhuset in Stockholm in September 2011. The incident, nicknamed "Tintin-gate", led to heated discussions in mainstream and social media concerning accusations of racism and censorship.[59] Complaints about the availability of the book in Sweden were also voiced by the Swedish-Belgian Jean-Dadaou Monyas, supported by Afrosvenskarna, an interest group for Swedes of African descent.[60] The complaint to the Chancellor of Justice was turned down as violations of hate speech restrictions in the Swedish Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression must be filed within one year of publication, and the latest Swedish edition of Tintin in the Congo appeared in 2005.[61]

Hunting and animal cruelty

Tintin in the Congo shows Tintin taking part in what Farr described as "the wholesale and gratuitous slaughter" of animals; over the course of the Adventure, Tintin shoots several antelope, kills an ape to wear its skin, rams a rifle vertically into a crocodile's open mouth, injures an elephant for ivory, stones a buffalo, and (in earlier editions) drills a hole into a rhinoceros before planting dynamite in its body, blowing it up from the inside.[11] Such scenes reflect the popularity of big-game hunting among affluent visitors in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 1930s.[11] Hergé later felt guilty about his portrayal of animals in Tintin in the Congo and became an opponent of blood sports; when he wrote Cigars of the Pharaoh (1934), he had Tintin befriend a herd of elephants living in the Indian jungle.[62]

Philippe Goddin stated that the scene in which Tintin shoots a herd of antelope was "enough to upset even the least ecological reader" in the 21st century.[63] When India Book House first published the book in India in 2006, its national branch of the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals issued a public criticism, and chief functionary Anuradha Sawhney stated that the book was "replete with instances that send a message to young minds that it is acceptable to be cruel to animals".[64]

References

Notes

- Babaor'om, a play on baba au rhum, "rum baba"[3]

- Boula Matari was a nickname for Henry Morton Stanley, an explorer who worked with King Leopold II to explore and annex the Congo Basin region as a private colony, the Congo Free State, during the late 19th century. The Free State was annexed by Belgium in 1908 and reorganised as the Belgian Congo.[4]

- M'Hatouvou, a play on m'as-tu vu, "show-off"[3]

- The first seven Tintin books averaged a print run of 17,000 copies; Tintin in the Congo's sales exceeded 25,000.[25]

- Hergé himself did not use the term ligne claire to describe his drawing style; the Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte first used the term in 1977.[27]

Footnotes

- Hergé 2005, pp. 1–11.

- Hergé 2005, pp. 11–18.

- Pellegrini 2013, p. 200.

- Ascherson 1999, pp. 128–9.

- Hergé 2005, pp. 19–28.

- Hergé 2005, pp. 44.

- Hergé 2005, pp. 44–52.

- Peeters 1989, pp. 31–32; Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25.

- Peeters 1989, pp. 20–32; Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25; Assouline 2009, p. 38.

- Thompson 1991, p. 24.

- Farr 2001, p. 22.

- Assouline 2009, p. 26; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 24.

- Assouline 2009, p. 26.

- Farr 2001, p. 21.

- Peeters 2012, p. 46.

- Thompson 1991, p. 33.

- Assouline 2009, p. 27.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 25.

- Assouline 2009, p. 27; Peeters 2012, p. 46.

- Assouline 2009, p. 28; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 24.

- Farr 2001, pp. 21–22.

- Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 26.

- Assouline 2009, p. 27; Farr 2001, p. 21.

- Assouline 2009, p. 28; Peeters 2012, p. 47; Thompson 1991, p. 41.

- McKinney 2008, p. 171.

- Peeters 2012, p. 47.

- Pleban 2006.

- Farr 2001, p. 25.

- Goddin 2009, pp. 70, 73.

- Thompson 1991, p. 42.

- Farr 2001, pp. 23, 25.

- Hergé 2005, inset.

- Peeters 2012, pp. 46–47.

- Goddin 2008, p. 75.

- Thompson 1991, p. 40.

- Kuper 2011.

- Peeters 1989, pp. 30–31.

- Apostolidès 2010, pp. 12–15.

- Apostolidès 2010, pp. 15–16.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 51.

- Cendrowicz 2010.

- McCarthy 2006, p. 37.

- Assouline 2009, p. 28.

- Apostolidès 2010, p. 14.

- Smith 2010.

- Assouline 2009, pp. 29–30.

- McKinney 2008, pp. 171–172.

- Farr 2001, p. 27; McCarthy 2006, p. 37.

- Thompson 1991, pp. 41–42.

- Cendrowicz 2010; BBC 2004.

- Mail & Guardian 2010; Heller 2011.

- Samuel 2011; BBC 2012.

- Vrielink 2012.

- Bunyan 2011.

- BBC 2007; Beckford 2007; Anon 2007, p. 14.

- Beckford 2007.

- Anon 2007, p. 14.

- Leigh Cowan 2009.

- Chukri 2012.

- Kalmteg 2007.

- Lindell 2007.

- Thompson 1991, p. 41.

- Goddin 2008, p. 70.

- Chopra 2006.

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal (1999) [1963]. The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (Reprint ed.). London: Granta. ISBN 1-86207-290-6.

- Anon (Summer 2007). "Racism in Children's Books: Tintin in the Congo". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. The JBHE Foundation. 56 (56): 14. JSTOR 25073692.

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- "DR Congo slams 'Tintin' minister". BBC News. 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- "Bid to ban 'racist' Tintin book". BBC News. 12 July 2007. Archived from the original on 22 August 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- "Tintin in the Congo not racist, court rules". BBC News. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Beckford, Martin (12 July 2007). "Ban 'racist' Tintin book, says CRE". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- Bunyan, Nigel (3 November 2011). "Tintin banned from children's shelves over 'racism' fears". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- Cendrowicz, Leo (4 May 2010). "Tintin: Heroic Boy Reporter or Sinister Racist?". Time. New York City. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Chopra, Arush (3 February 2006). "Tintin in trouble: Congo book slammed". Daily News Analysis. Mumbai. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Chukri, Rakel (6 October 2012). "Vad handlar Tintin-gate om?" [What is Tintin-gate about?]. Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). Malmö, Sweden. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Goddin, Philippe (2008). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume I, 1907–1937. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

- Goddin, Philippe (2009). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume 2: 1937–1949. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-724-2.

- Heller, Maxwell (10 December 2011). "Picturing South Africa in New York". The Brooklyn Mail. New York City. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Hergé (2005) [1946]. Tintin in the Congo. Translated by Lonsdale-Cooper, Leslie; Turner, Michael. London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4052-2098-9.

- Hunt, N. R. (2002). "Tintin and the Interruptions of Congolese Comics". In Landau, P. S.; Kaspin, D. D. (eds.). Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22949-5.

- Kalmteg, Lina (23 August 2007). "Tintin-serie "hets mot folkgrupp"" [Tintin series "hate speech"]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Kuper, Simon (11 October 2011). "Tintin and the war". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Leigh Cowan, Alison (19 August 2009). "A Library's Approach to Books That Offend". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Lindell, Karin (22 August 2007). "JK vidtar ingen åtgärd i Tintin-ärendet" [JK takes no action in Tintin matter]. Medievärlden (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- "Pappa in Afrika". Mail & Guardian. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- McKinney, Mark (2008). History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-761-5.

- Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Pellegrini, G. A. (2013). (Not) looking together in the same direction: A comparative study of representations of Latin America in a selection of Franco-Belgian and Latin American comics (PhD thesis) (PDF). Sydney: University of Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015.

- Pleban, Dafna (7 November 2006). "Investigating the Clear Line Style". ComicFoundry. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- Samuel, Henry (18 October 2011). "Tintin 'racist' court case nears its conclusion after four years". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Smith, Neil (28 April 2010). "Race row continues to dog Tintin's footsteps". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

- Vrielink, Jogchum (14 May 2012). "Effort to ban Tintin comic book fails in Belgium". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

External links

- Tintin in the Congo at the Official Tintin Website

- Tintin in the Congo at Tintinologist.org