Tosca

Tosca is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It premiered at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome on 14 January 1900. The work, based on Victorien Sardou's 1887 French-language dramatic play, La Tosca, is a melodramatic piece set in Rome in June 1800, with the Kingdom of Naples's control of Rome threatened by Napoleon's invasion of Italy. It contains depictions of torture, murder, and suicide, as well as some of Puccini's best-known lyrical arias.

| Tosca | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Giacomo Puccini | |

.jpg.webp) Original poster, depicting the death of Scarpia | |

| Librettist |

|

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | La Tosca by Victorien Sardou |

| Premiere | 14 January 1900 Teatro Costanzi, Rome |

Puccini saw Sardou's play when it was touring Italy in 1889 and, after some vacillation, obtained the rights to turn the work into an opera in 1895. Turning the wordy French play into a succinct Italian opera took four years, during which the composer repeatedly argued with his librettists and publisher. Tosca premiered at a time of unrest in Rome, and its first performance was delayed for a day for fear of disturbances. Despite indifferent reviews from the critics, the opera was an immediate success with the public.

Musically, Tosca is structured as a through-composed work, with arias, recitative, choruses and other elements musically woven into a seamless whole. Puccini used Wagnerian leitmotifs to identify characters, objects and ideas. While critics have often dismissed the opera as a facile melodrama with confusions of plot—musicologist Joseph Kerman famously called it a "shabby little shocker"[1][2][3]—the power of its score and the inventiveness of its orchestration have been widely acknowledged. The dramatic force of Tosca and its characters continues to fascinate both performers and audiences, and the work remains one of the most frequently performed operas. Many recordings of the work have been issued, both of studio and live performances.

Background

The French playwright Victorien Sardou wrote more than 70 plays, almost all of them successful, and none of them performed today.[4] In the early 1880s Sardou began a collaboration with actress Sarah Bernhardt, whom he provided with a series of historical melodramas.[5] His third Bernhardt play, La Tosca, which premiered in Paris on 24 November 1887, and in which she starred throughout Europe, was an outstanding success, with more than 3,000 performances in France alone.[6][7]

Puccini had seen La Tosca at least twice, in Milan and Turin. On 7 May 1889 he wrote to his publisher, Giulio Ricordi, begging him to get Sardou's permission for the work to be made into an opera: "I see in this Tosca the opera I need, with no overblown proportions, no elaborate spectacle, nor will it call for the usual excessive amount of music."[8]

Ricordi sent his agent in Paris, Emanuele Muzio, to negotiate with Sardou, who preferred that his play be adapted by a French composer. He complained about the reception La Tosca had received in Italy, particularly in Milan, and warned that other composers were interested in the piece.[9] Nonetheless, Ricordi reached terms with Sardou and assigned the librettist Luigi Illica to write a scenario for an adaptation.[10]

In 1891, Illica advised Puccini against the project, most likely because he felt the play could not be successfully adapted to a musical form.[11] When Sardou expressed his unease at entrusting his most successful work to a relatively new composer whose music he did not like, Puccini took offence. He withdrew from the agreement,[12] which Ricordi then assigned to the composer Alberto Franchetti.[10] Illica wrote a libretto for Franchetti, who was never at ease with the assignment.

When Puccini once again became interested in Tosca, Ricordi was able to get Franchetti to surrender the rights so he could recommission Puccini.[13] One story relates that Ricordi convinced Franchetti that the work was too violent to be successfully staged. A Franchetti family tradition holds that Franchetti gave the work back as a grand gesture, saying, "He has more talent than I do."[10] American scholar Deborah Burton contends that Franchetti gave it up simply because he saw little merit in it and could not feel the music in the play.[10] Whatever the reason, Franchetti surrendered the rights in May 1895, and in August Puccini signed a contract to resume control of the project.[13]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 14 January 1900[14] Conductor: Leopoldo Mugnone[15] |

|---|---|---|

| Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer | soprano | Hariclea Darclée |

| Mario Cavaradossi, a painter | tenor | Emilio De Marchi |

| Baron Scarpia, chief of police | baritone | Eugenio Giraldoni |

| Cesare Angelotti, former Consul of the Roman Republic | bass | Ruggero Galli |

| A Sacristan | bass | Ettore Borelli |

| Spoletta, a police agent | tenor | Enrico Giordano |

| Sciarrone, another agent | bass | Giuseppe Gironi |

| A Jailer | bass | Aristide Parassani |

| A Shepherd boy | boy soprano | Angelo Righi |

| Soldiers, police agents, altar boys, noblemen and women, townsfolk, artisans | ||

Synopsis

Historical context

According to the libretto, the action of Tosca occurs in Rome in June 1800.[16] Sardou, in his play, dates it more precisely; La Tosca takes place in the afternoon, evening, and early morning of 17 and 18 June 1800.[17]

Italy had long been divided into a number of small states, with the Pope in Rome ruling the Papal States in Central Italy. Following the French Revolution, a French army under Napoleon invaded Italy in 1796, entering Rome almost unopposed on 11 February 1798 and establishing a republic there.[18] Pope Pius VI was taken prisoner, and was sent into exile on February 20, 1798. (Pius VI would die in exile in 1799, and his successor, Pius VII, who was elected in Venice on 14 March 1800, would not enter Rome until July 3. There is thus neither a Pope nor papal government in Rome during the days depicted in the opera.) The new republic was ruled by seven consuls; in the opera this is the office formerly held by Angelotti, whose character may be based on the real-life consul Liborio Angelucci.[19] In September 1799 the French, who had protected the republic, withdrew from Rome.[20] As they left, troops of the Kingdom of Naples occupied the city.[21]

In May 1800 Napoleon, by then the undisputed leader of France, brought his troops across the Alps to Italy once again. On 14 June his army met the Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo (near Alessandria). Austrian troops were initially successful; by mid-morning they were in control of the field of battle. Their commander, Michael von Melas, sent this news south towards Rome. However, fresh French troops arrived in late afternoon, and Napoleon attacked the tired Austrians. As Melas retreated in disarray with the remains of his army, he sent a second courier south with the revised message.[22] The Neapolitans abandoned Rome,[23] and the city spent the next fourteen years under French domination.[24]

Act 1

Inside the church of Sant'Andrea della Valle

Cesare Angelotti, former consul of the Roman Republic and now an escaped political prisoner, runs into the church and hides in the Attavanti private chapel – his sister, the Marchesa Attavanti, has left a key to the chapel hidden at the feet of the statue of the Madonna. The elderly Sacristan enters and begins cleaning. The Sacristan kneels in prayer as the Angelus sounds.

The painter Mario Cavaradossi arrives to continue work on his picture of Mary Magdalene. The Sacristan identifies a likeness between the portrait and a blonde-haired woman who has been visiting the church recently (unknown to him, it is Angelotti's sister the Marchesa). Cavaradossi describes the "hidden harmony" ("Recondita armonia") in the contrast between the blonde beauty of his painting and his dark-haired lover, the singer Floria Tosca. The Sacristan mumbles his disapproval before leaving.

Angelotti emerges and tells Cavaradossi, an old friend who has republican sympathies, that he is being pursued by the Chief of Police, Baron Scarpia. Cavaradossi promises to assist him after nightfall. Tosca's voice is heard, calling to Cavaradossi. Cavaradossi gives Angelotti his basket of food and Angelotti hurriedly returns to his hiding place.

Tosca enters and suspiciously asks Cavaradossi what he has been doing – she thinks that he has been talking to another woman. After Cavaradossi reassures her, Tosca tries to persuade him to take her to his villa that evening: "Non la sospiri, la nostra casetta" ("Do you not long for our little cottage"). She then expresses jealousy over the woman in the painting, whom she recognises as the Marchesa Attavanti. Cavaradossi explains the likeness; he has merely observed the Marchesa at prayer in the church. He reassures Tosca of his fidelity and asks her what eyes could be more beautiful than her own: "Qual'occhio al mondo" ("What eyes in the world").

After Tosca has left, Angelotti reappears and discusses with the painter his plan to flee disguised as a woman, using clothes left in the chapel by his sister. Cavaradossi gives Angelotti a key to his villa, suggesting that he hide in a disused well in the garden. The sound of a cannon signals that Angelotti's escape has been discovered. He and Cavaradossi hasten out of the church.

The Sacristan re-enters with choristers, celebrating the news that Napoleon has apparently been defeated at Marengo. The celebrations cease abruptly with the entry of Scarpia, his henchman Spoletta and several police agents. They have heard that Angelotti has sought refuge in the church. Scarpia orders a search, and the empty food basket and a fan bearing the Attavanti coat of arms are found in the chapel. Scarpia questions the Sacristan, and his suspicions are aroused further when he learns that Cavaradossi has been in the church; Scarpia mistrusts the painter, and believes him complicit in Angelotti's escape.

When Tosca arrives looking for her lover, Scarpia artfully arouses her jealous instincts by implying a relationship between the painter and the Marchesa Attavanti. He draws Tosca's attention to the fan and suggests that someone must have surprised the lovers in the chapel. Tosca falls for his deceit; enraged, she rushes off to confront Cavaradossi. Scarpia orders Spoletta and his agents to follow her, assuming she will lead them to Cavaradossi and Angelotti. He privately gloats as he reveals his intentions to possess Tosca and execute Cavaradossi. A procession enters the church singing the Te Deum; exclaiming 'Tosca, you make me forget even God!', Scarpia joins the chorus in the prayer.

Act 2

Scarpia's apartment in the Palazzo Farnese, that evening

Scarpia, at supper, sends a note to Tosca asking her to come to his apartment, anticipating that two of his goals will soon be fulfilled at once. His agent, Spoletta, arrives to report that Angelotti remains at large, but Cavaradossi has been arrested for questioning. He is brought in, and an interrogation ensues. As the painter steadfastly denies knowing anything about Angelotti's escape, Tosca's voice is heard singing a celebratory cantata elsewhere in the Palace.

She enters the apartment in time to see Cavaradossi being escorted to an antechamber. All he has time to say is that she mustn't tell them anything. Scarpia then claims she can save her lover from indescribable pain if she reveals Angelotti's hiding place. She resists, but the sound of screams coming through the door eventually breaks her down, and she tells Scarpia to search the well in the garden of Cavaradossi's villa.

Scarpia orders his torturers to cease, and the bloodied painter is dragged back in. He is devastated to discover that Tosca has betrayed his friend. Sciarrone, another agent, then enters with news: there was an upset on the battlefield at Marengo, and the French are marching on Rome. Cavaradossi, unable to contain himself, gloats to Scarpia that his rule of terror will soon be at an end. This is enough for the police to consider him guilty, and they haul him away to be executed.

Scarpia, now alone with Tosca, proposes a bargain: if she gives herself to him, Cavaradossi will be freed. She is revolted, and repeatedly rejects his advances, but she hears the drums outside announcing an execution. As Scarpia awaits her decision, she prays, asking why God has abandoned her in her hour of need: "Vissi d'arte" ("I lived for art"). She tries to offer money, but Scarpia is not interested in that kind of bribe: he wants Tosca herself.

Spoletta returns with the news that Angelotti has killed himself upon discovery, and that everything is in place for Cavaradossi's execution. Scarpia hesitates to give the order, looking to Tosca, and despairingly she agrees to submit to him. He tells Spoletta to arrange a mock execution, both men repeating that it will be "as we did with Count Palmieri", and Spoletta exits.

Tosca insists that Scarpia must provide safe-conduct out of Rome for herself and Cavaradossi. He easily agrees to this and heads to his desk. While he's drafting the document, she quietly takes a knife from the supper table. Scarpia triumphantly strides toward Tosca. When he begins to embrace her, she stabs him, crying "this is Tosca's kiss!" Once she's certain he's dead, she ruefully says "now I forgive him." She removes the safe-conduct from his pocket, lights candles in a gesture of piety, and places a crucifix on the body before leaving.

Act 3

The upper parts of the Castel Sant'Angelo, early the following morning

.jpg.webp)

A shepherd boy is heard offstage singing (in Romanesco dialect) "Io de' sospiri" ("I give you sighs") as church bells sound for matins. The guards lead Cavaradossi in and a jailer informs him that he has one hour to live. He declines to see a priest, but asks permission to write a letter to Tosca. He begins to write, but is soon overwhelmed by memories: "E lucevan le stelle" ("And the stars shone").

Tosca enters and shows him the safe-conduct pass she has obtained, adding that she has killed Scarpia and that the imminent execution is a sham. Cavaradossi must feign death, after which they can flee together before Scarpia's body is discovered. Cavaradossi is awestruck by his gentle lover's courage: "O dolci mani" ("Oh sweet hands"). The pair ecstatically imagine the life they will share, far from Rome. Tosca then anxiously coaches Cavaradossi on how to play dead when the firing squad shoots at him with blanks. He promises he will fall "like Tosca in the theatre".

Cavaradossi is led away, and Tosca watches with increasing impatience as the firing squad prepares. The men fire, and Tosca praises the realism of his fall, "Ecco un artista!" ("What an actor!"). Once the soldiers have left, she hurries towards Cavaradossi, urging him, "Mario, su presto!" ("Mario, up quickly!"), only to find that Scarpia betrayed her: the bullets were real. Heartbroken, she clasps her lover's lifeless body and weeps.

The voices of Spoletta, Sciarrone, and the soldiers are heard, shouting that Scarpia is dead and Tosca has killed him. As the men rush in, Tosca rises, evades their clutches, and runs to the parapet. Crying "O Scarpia, avanti a Dio!" ("O Scarpia, we meet before God!"), she flings herself over the edge to her death.

Adaptation and writing

Sardou's five-act play La Tosca contains a large amount of dialogue and exposition. While the broad details of the play are present in the opera's plot, the original work contains many more characters and much detail not present in the opera. In the play the lovers are portrayed as though they were French: the character Floria Tosca is closely modelled on Bernhardt's personality, while her lover Cavaradossi, of Roman descent, is born in Paris. Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, the playwright who joined the project to polish the verses, needed not only to cut back the play drastically, but to make the characters' motivations and actions suitable for Italian opera.[25] Giacosa and Puccini repeatedly clashed over the condensation, with Giacosa feeling that Puccini did not really want to complete the project.[26]

The first draft libretto that Illica produced for Puccini resurfaced in 2000 after being lost for many years. It contains considerable differences from the final libretto, relatively minor in the first two acts but much more appreciable in the third, where the description of the Roman dawn that opens the third act is much longer, and Cavaradossi's tragic aria, the eventual "E lucevan le stelle", has different words. The 1896 libretto also offers a different ending, in which Tosca does not die but instead goes mad. In the final scene, she cradles her lover's head in her lap and hallucinates that she and her Mario are on a gondola, and that she is asking the gondolier for silence.[27] Sardou refused to consider this change, insisting that as in the play, Tosca must throw herself from the parapet to her death.[28] Puccini agreed with Sardou, telling him that the mad scene would have the audiences anticipate the ending and start moving towards the cloakrooms. Puccini pressed his librettists hard, and Giacosa issued a series of melodramatic threats to abandon the work.[29] The two librettists were finally able to give Puccini what they hoped was a final version of the libretto in 1898.[30]

Little work was done on the score during 1897, which Puccini devoted mostly to performances of La bohème.[30] The opening page of the autograph Tosca score, containing the motif that would be associated with Scarpia, is dated January 1898.[31] At Puccini's request, Giacosa irritably provided new lyrics for the act 1 love duet. In August, Puccini removed several numbers from the opera, according to his biographer, Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, "cut[ting] Tosca to the bone, leaving three strong characters trapped in an airless, violent, tightly wound melodrama that had little room for lyricism".[32] At the end of the year, Puccini wrote that he was "busting his balls" on the opera.[32]

Puccini asked clerical friends for words for the congregation to mutter at the start of the act 1 Te Deum; when nothing they provided satisfied him, he supplied the words himself.[32] For the Te Deum music, he investigated the melodies to which the hymn was set in Roman churches, and sought to reproduce the cardinal's procession authentically, even to the uniforms of the Swiss Guards.[29] He adapted the music to the exact pitch of the great bell of St. Peter's Basilica,[33][29] and was equally diligent when writing the music that opens act 3, in which Rome awakens to the sounds of church bells.[33][29] He journeyed to Rome and went to the Castel Sant'Angelo to measure the sound of matins bells there, as they would be heard from its ramparts.[29] Puccini had bells for the Roman dawn cast to order by four different foundries.[34] This apparently did not have its desired effect, as Illica wrote to Ricordi on the day after the premiere, "the great fuss and the large amount of money for the bells have constituted an additional folly, because it passes completely unnoticed".[35] Nevertheless, the bells provide a source of trouble and expense to opera companies performing Tosca to this day.[28]

In act 2, when Tosca sings offstage the cantata that celebrates the supposed defeat of Napoleon, Puccini was tempted to follow the text of Sardou's play and use the music of Giovanni Paisiello, before finally writing his own imitation of Paisello's style.[36] It was not until 29 September 1899 that Puccini was able to mark the final page of the score as completed. Despite the notation, there was additional work to be done,[37] such as the shepherd boy's song at the start of act 3. Puccini, who always sought to put local colour in his works, wanted that song to be in Roman dialect. The composer asked a friend to have a "good romanesco poet" write some words; eventually the poet and folklorist Luigi "Giggi" Zanazzo wrote the verse which, after slight modification, was placed in the opera.[37]

In October 1899, Ricordi realized that some of the music for Cavaradossi's act 3 aria, "O dolci mani" was borrowed from music Puccini had cut from his early opera, Edgar and demanded changes. Puccini defended his music as expressive of what Cavaradossi must be feeling at that point, and offered to come to Milan to play and sing act 3 for the publisher.[38] Ricordi was overwhelmed by the completed act 3 prelude, which he received in early November, and softened his views, though he was still not completely happy with the music for "O dolci mani".[39] In any event time was too short before the scheduled January 1900 premiere to make any further changes.[40]

Reception and performance history

Premiere

By December 1899, Tosca was in rehearsal at the Teatro Costanzi.[41] Because of the Roman setting, Ricordi arranged a Roman premiere for the opera,[29] even though this meant that Arturo Toscanini could not conduct it as Puccini had planned—Toscanini was fully engaged at La Scala in Milan. Leopoldo Mugnone was appointed to conduct. The accomplished (but temperamental) soprano Hariclea Darclée was selected for the title role; Eugenio Giraldoni, whose father had originated many Verdi roles, became the first Scarpia. The young Enrico Caruso had hoped to create the role of Cavaradossi, but was passed over in favour of the more experienced Emilio De Marchi.[41] The performance was to be directed by Nino Vignuzzi, with stage designs by Adolfo Hohenstein.[42]

At the time of the premiere, Italy had experienced political and social unrest for several years. The start of the Holy Year in December 1899 attracted the religious to the city, but also brought threats from anarchists and other anticlericals. Police received warnings of an anarchist bombing of the theatre, and instructed Mugnone (who had survived a theatre bombing in Barcelona),[43] that in an emergency he was to strike up the royal march.[44] The unrest caused the premiere to be postponed by one day, to 14 January.[45]

By 1900, the premiere of a Puccini opera was a national event.[44] Many Roman dignitaries attended, as did Queen Margherita, though she arrived late, after the first act.[43] The Prime Minister of Italy, Luigi Pelloux was present, with several members of his cabinet.[45] A number of Puccini's operatic rivals were there, including Franchetti, Pietro Mascagni, Francesco Cilea and Ildebrando Pizzetti. Shortly after the curtain was raised there was a disturbance in the back of the theatre, caused by latecomers attempting to enter the auditorium, and a shout of "Bring down the curtain!", at which Mugnone stopped the orchestra.[43] A few moments later the opera began again, and proceeded without further disruption.[43]

The performance, while not quite the triumph that Puccini had hoped for, was generally successful, with numerous encores.[43] Much of the critical and press reaction was lukewarm, often blaming Illica's libretto. In response, Illica condemned Puccini for treating his librettists "like stagehands" and reducing the text to a shadow of its original form.[46] Nevertheless, any public doubts about Tosca soon vanished; the premiere was followed by twenty performances, all given to packed houses.[47]

Subsequent productions

The Milan premiere at La Scala took place under Toscanini on 17 March 1900. Darclée and Giraldoni reprised their roles; the prominent tenor Giuseppe Borgatti replaced De Marchi as Cavaradossi. The opera was a great success at La Scala, and played to full houses.[48] Puccini travelled to London for the British premiere at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, on 12 July, with Milka Ternina and Fernando De Lucia as the doomed lovers and Antonio Scotti as Scarpia. Puccini wrote that Tosca was "[a] complete triumph", and Ricordi's London representative quickly signed a contract to take Tosca to New York. The premiere at the Metropolitan Opera was on 4 February 1901, with De Lucia's replacement by Giuseppe Cremonini the only change from the London cast.[49] For its French premiere at the Opéra-Comique on 13 October 1903, the 72-year-old Sardou took charge of all the action on the stage. Puccini was delighted with the public's reception of the work in Paris, despite adverse comments from critics. The opera was subsequently premiered at venues throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and the Far East;[50] by the outbreak of war in 1914 it had been performed in more than 50 cities worldwide.[14]

Among the prominent early Toscas was Emmy Destinn, who sang the role regularly in a long-standing partnership with the tenor Enrico Caruso.[51] Maria Jeritza, over many years at the Met and in Vienna, brought her own distinctive style to the role, and was said to be Puccini's favorite Tosca.[52] Jeritza was the first to deliver "Vissi d'arte" from a prone position, having fallen to the stage while eluding the grasp of Scarpia. This was a great success, and Jeritza sang the aria while on the floor thereafter.[53] Of her successors, opera enthusiasts tend to consider Maria Callas as the supreme interpreter of the role, largely on the basis of her performances at the Royal Opera House in 1964, with Tito Gobbi as Scarpia.[52] This production, by Franco Zeffirelli, remained in continuous use at Covent Garden for more than 40 years until replaced in 2006 by a new staging, which premiered with Angela Gheorghiu. Callas had first sung Tosca at age 18 in a performance given in Greek, in the Greek National Opera in Athens on 27 August 1942.[54] Tosca was also her last on-stage operatic role, in a special charity performance at the Royal Opera House on 7 May 1965.[55]

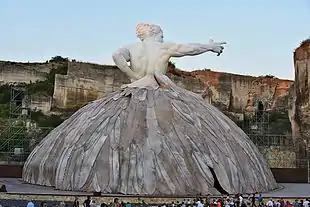

Among non-traditional productions, Luca Ronconi, in 1996 at La Scala, used distorted and fractured scenery to represent the twists of fate reflected in the plot.[52] Jonathan Miller, in a 1986 production for the 49th Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, transferred the action to Nazi-occupied Rome in 1944, with Scarpia as head of the fascist police.[56] In Philipp Himmelmann's production on the Lake Stage at the Bregenz Festival in 2007 the act 1 set, designed by Johannes Leiacker, was dominated by a huge Orwellian "Big Brother" eye. The iris opens and closes to reveal surreal scenes beyond the action. This production updates the story to a modern Mafia scenario, with special effects "worthy of a Bond film".[57]

In 1992 a television version of the opera was filmed at the locations prescribed by Puccini, at the times of day at which each act takes place. Featuring Catherine Malfitano, Plácido Domingo and Ruggero Raimondi, the performance was broadcast live throughout Europe.[58] Luciano Pavarotti, who sang Cavaradossi from the late 1970s, appeared in a special performance in Rome, with Plácido Domingo as conductor, on 14 January 2000, to celebrate the opera's centenary. Pavarotti's last stage performance was as Cavaradossi at the Met, on 13 March 2004.[59]

Early Cavaradossis played the part as if the painter believed that he was reprieved, and would survive the "mock" execution. Beniamino Gigli, who performed the role many times in his forty-year operatic career, was one of the first to assume that the painter knows, or strongly suspects, that he will be shot. Gigli wrote in his autobiography: "he is certain that these are their last moments together on earth, and that he is about to die".[60] Domingo, the dominant Cavaradossi of the 1970s and 1980s, concurred, stating in a 1985 interview that he had long played the part that way.[60] Gobbi, who in his later years often directed the opera, commented, "Unlike Floria, Cavaradossi knows that Scarpia never yields, though he pretends to believe in order to delay the pain for Tosca."[60]

Critical reception

The enduring popularity of Tosca has not been matched by consistent critical enthusiasm. After the premiere, Ippolito Valetta of Nuova antologia wrote, "[Puccini] finds in his palette all colours, all shades; in his hands, the instrumental texture becomes completely supple, the gradations of sonority are innumerable, the blend unfailingly grateful to the ear."[47][61] However, one critic described act 2 as overly long and wordy; another echoed Illica and Giacosa in stating that the rush of action did not permit enough lyricism, to the great detriment of the music. A third called the opera "three hours of noise".[62]

The critics gave the work a generally kinder reception in London, where The Times called Puccini "a master in the art of poignant expression", and praised the "wonderful skill and sustained power" of the music.[63] In The Musical Times, Puccini's score was admired for its sincerity and "strength of utterance."[64] After the 1903 Paris opening, the composer Paul Dukas thought the work lacked cohesion and style, while Gabriel Fauré was offended by "disconcerting vulgarities".[63][50] In the 1950s, the young musicologist Joseph Kerman described Tosca as a "shabby little shocker.";[1] in response the conductor Thomas Beecham remarked that anything Kerman says about Puccini "can safely be ignored".[65] Writing half a century after the premiere, the veteran critic Ernest Newman, while acknowledging the "enormously difficult business of boiling [Sardou's] play down for operatic purposes", thought that the subtleties of Sardou's original plot are handled "very lamely", so that "much of what happens, and why, is unintelligible to the spectator".[66] Overall, however, Newman delivered a more positive judgement: "[Puccini's] operas are to some extent a mere bundle of tricks, but no one else has performed the same tricks nearly as well".[67] Opera scholar Julian Budden remarks on Puccini's "inept handling of the political element", but still hails the work as "a triumph of pure theatre".[68] Music critic Charles Osborne ascribes Tosca's immense popularity with audiences to the taut effectiveness of its melodramatic plot, the opportunities given to its three leading characters to shine vocally and dramatically, and the presence of two great arias in "Vissi d'arte" and "E lucevan le stelle".[69] The work remains popular today: according to Operabase, it ranks as fifth in the world with 540 performances given in the five seasons 2009–10 to 2013–14.[70]

Music

General style

By the end of the 19th century the classic form of opera structure, in which arias, duets and other set-piece vocal numbers are interspersed with passages of recitative or dialogue, had been largely abandoned, even in Italy. Operas were "through-composed", with a continuous stream of music which in some cases eliminated all identifiable set-pieces. In what critic Edward Greenfield calls the "Grand Tune" concept, Puccini retains a limited number of set-pieces, distinguished from their musical surroundings by their memorable melodies. Even in the passages linking these "Grand Tunes", Puccini maintains a strong degree of lyricism and only rarely resorts to recitative.[71]

Budden describes Tosca as the most Wagnerian of Puccini's scores, in its use of musical leitmotifs. Unlike Wagner, Puccini does not develop or modify his motifs, nor weave them into the music symphonically, but uses them to refer to characters, objects and ideas, and as reminders within the narrative.[72] The most potent of these motifs is the sequence of three very loud and strident chords which open the opera and which represent the evil character of Scarpia—or perhaps, Charles Osborne proposes, the violent atmosphere that pervades the entire opera.[73] Budden has suggested that Scarpia's tyranny, lechery and lust form "the dynamic engine that ignites the drama".[74] Other motifs identify Tosca herself, the love of Tosca and Cavaradossi, the fugitive Angelotti, the semi-comical character of the sacristan in act 1 and the theme of torture in act 2.[74][75]

Act 1

The opera begins without any prelude; the opening chords of the Scarpia motif lead immediately to the agitated appearance of Angelotti and the enunciation of the "fugitive" motif. The sacristan's entry, accompanied by his sprightly buffo theme, lifts the mood, as does the generally light-hearted colloquy with Cavaradossi which follows after the latter's entrance. This leads to the first of the "Grand Tunes", Cavaradossi's "Recondita armonia" with its sustained high B flat, accompanied by the sacristan's grumbling counter-melody.[73] The domination, in that aria, of themes which will be repeated in the love duet make it clear that though the painting may incorporate the Marchesa's features, Tosca is the ultimate inspiration of his work.[76] Cavaradossi's dialogue with Angelotti is interrupted by Tosca's arrival, signalled by her motif which incorporates, in Newman's words, "the feline, caressing cadence so characteristic of her."[77] Though Tosca enters violently and suspiciously, the music paints her devotion and serenity. According to Budden, there is no contradiction: Tosca's jealousy is largely a matter of habit, which her lover does not take too seriously.[78]

After Tosca's "Non la sospiri" and the subsequent argument inspired by her jealousy, the sensuous character of the love duet "Qual'occhio" provides what opera writer Burton Fisher describes as "an almost erotic lyricism that has been called pornophony".[33] The brief scene in which the sacristan returns with the choristers to celebrate Napoleon's supposed defeat provides almost the last carefree moments in the opera; after the entrance of Scarpia to his menacing theme, the mood becomes sombre, then steadily darker.[36] As the police chief interrogates the sacristan, the "fugitive" motif recurs three more times, each time more emphatically, signalling Scarpia's success in his investigation.[79] In Scarpia's exchanges with Tosca the sound of tolling bells, interwoven with the orchestra, creates an almost religious atmosphere,[36] for which Puccini draws on music from his then unpublished Mass of 1880.[80] The final scene in the act is a juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane,[75] as Scarpia's lustful reverie is sung alongside the swelling Te Deum chorus. He joins with the chorus in the final statement "Te aeternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur" ("Everlasting Father, all the earth worships thee"), before the act ends with a thunderous restatement of the Scarpia motif.[75][81]

Act 2

In the second act of Tosca, according to Newman, Puccini rises to his greatest height as a master of the musical macabre.[82] The act begins quietly, with Scarpia musing on the forthcoming downfall of Angelotti and Cavaradossi, while in the background a gavotte is played in a distant quarter of the Farnese Palace. For this music Puccini adapted a fifteen-year-old student exercise by his late brother, Michele, stating that in this way his brother could live again through him.[83] In the dialogue with Spoletta, the "torture" motif—an "ideogram of suffering", according to Budden—is heard for the first time as a foretaste of what is to come.[36][84] As Cavaradossi is brought in for interrogation, Tosca's voice is heard with the offstage chorus singing a cantata, "[its] suave strains contrast[ing] dramatically with the increasing tension and ever-darkening colour of the stage action".[85] The cantata is most likely the Cantata a Giove, in the literature referred to as a lost work of Puccini's from 1897.[83]

Osborne describes the scenes that follow—Cavaradossi's interrogation, his torture, Scarpia's sadistic tormenting of Tosca—as Puccini's musical equivalent of grand guignol to which Cavaradossi's brief "Vittoria! Vittoria!" on the news of Napoleon's victory gives only partial relief.[86] Scarpia's aria "Già, mi dicon venal" ("Yes, they say I am venal") is closely followed by Tosca's "Vissi d'arte". A lyrical andante based on Tosca's act 1 motif, this is perhaps the opera's best-known aria, yet was regarded by Puccini as a mistake;[87] he considered eliminating it since it held up the action.[88] Fisher calls it "a Job-like prayer questioning God for punishing a woman who has lived unselfishly and righteously".[75] In the act's finale, Newman likens the orchestral turmoil which follows Tosca's stabbing of Scarpia to the sudden outburst after the slow movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.[89] After Tosca's contemptuous "E avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma!" ("All Rome trembled before him"), sung on a middle C♯ monotone [90] (sometimes spoken),[86] the music gradually fades, ending what Newman calls "the most impressively macabre scene in all opera."[91] The final notes in the act are those of the Scarpia motif, softly, in a minor key.[92]

Act 3

The third act's tranquil beginning provides a brief respite from the drama. An introductory 16-bar theme for the horns will later be sung by Cavaradossi and Tosca in their final duet. The orchestral prelude which follows portrays the Roman dawn; the pastoral aura is accentuated by the shepherd boy's song, and the sounds of sheep bells and church bells, the authenticity of the latter validated by Puccini's early morning visits to Rome.[33][86] Themes reminiscent of Scarpia, Tosca and Cavaradossi emerge in the music, which changes tone as the drama resumes with Cavaradossi's entrance, to an orchestral statement of what becomes the melody of his aria "E lucevan le stelle".[86]

This is a farewell to love and life, "an anguished lament and grief built around the words 'muoio disperato' (I die in despair)".[93] Puccini insisted on the inclusion of these words, and later stated that admirers of the aria had treble cause to be grateful to him: for composing the music, for having the lyrics written, and "for declining expert advice to throw the result in the waste-paper basket".[94] The lovers' final duet "Amaro sol per te", which concludes with the act's opening horn music, did not equate with Ricordi's idea of a transcendental love duet which would be a fitting climax to the opera. Puccini justified his musical treatment by citing Tosca's preoccupation with teaching Cavaradossi to feign death.[72]

In the execution scene which follows, a theme emerges, the incessant repetition of which reminded Newman of the Transformation Music which separates the two parts of act 1 in Wagner's Parsifal.[95] In the final bars, as Tosca evades Spoletta and leaps to her death, the theme of "E lucevan le stelle" is played tutta forze (as loudly as possible). This choice of ending has been strongly criticised by analysts, mainly because of its specific association with Cavaradossi rather than Tosca.[68] Kerman mocked the final music, "Tosca leaps, and the orchestra screams the first thing that comes into its head."[96] Budden, however, argues that it is entirely logical to end this dark opera on its blackest theme.[68] According to historian and former opera singer Susan Vandiver Nicassio: "The conflict between the verbal and the musical clues gives the end of the opera a twist of controversy that, barring some unexpected discovery among Puccini's papers, can never truly be resolved."[96]

Instrumentation

Tosca is scored for three flutes (the second and third doubling piccolo); two oboes; one English horn; two clarinets in B-flat; one bass clarinet in B-flat; two bassoons; one contrabassoon; four French horns in F; three trumpets in F; three tenor trombones; one bass trombone; a percussion section with timpani, cymbals, cannon, one triangle, one bass drum, one glockenspiel, and six church bells; one celesta, one pipe organ; one harp; and strings.[97]

List of arias and set numbers

| First lines | Performed by |

|---|---|

| Act 1 | |

| "Recondita armonia" ("Hidden harmony") |

Cavaradossi |

| "Non la sospiri, la nostra casetta" ("Do you not long for our little house") |

Tosca, Cavaradossi |

| "Qual'occhio" ("What eyes in the world") |

Cavaradossi, Tosca |

| "Va, Tosca!" ("Go, Tosca!") |

Scarpia, Chorus |

| Te Deum laudamus ("We praise thee, O God") |

Scarpia, Chorus |

| Act 2 | |

| "Ha più forte sapore" ("For myself the violent conquest") |

Scarpia |

| "Vittoria! Vittoria!" ("Victory! Victory!") |

Cavaradossi |

| "Già, mi dicon venal" ("Yes, they say that I am venal") |

Scarpia |

| "Vissi d'arte" ("I lived for art, I lived for love") |

Tosca |

| Act 3 | |

| "Io de' sospiri" ("I give you sighs") |

Voice of a shepherd boy |

| "E lucevan le stelle" ("And the stars shone") |

Cavaradossi |

| "O dolci mani" ("Oh, sweet hands") |

Cavaradossi |

| "Amaro sol per te m'era il morire" ("Only for you did death taste bitter for me") |

Cavaradossi, Tosca |

Recordings

The first complete Tosca recording was made in 1918, using the acoustic process. The conductor, Carlo Sabajno, had been the Gramophone Company's house conductor since 1904; he had made early complete recordings of several operas, including Verdi's La traviata and Rigoletto, before tackling Tosca with a largely unknown cast, featuring the Italian soprano Lya Remondini in the title role. The next year, in 1919, Sabajno recorded Tosca again, this time with more well-known singers, including Valentina Bartolomasi and Attilio Salvaneschi as Tosca and Cavaradossi. Ten years later, in 1929, Sabajno returned to the opera for the third time, recording it, by the electrical process, with the orchestra and chorus of the Teatro alla Scala and with stars Carmen Melis and Apollo Granforte in the roles of Tosca and Scarpia.[98][99] In 1938 HMV secured the services of the renowned tenor Beniamino Gigli, together with the soprano Maria Caniglia as Tosca and conductor Oliviero De Fabritiis, for a "practically complete" recording that extended over 14 double-sided shellac discs.[100]

In the post-war period, following the invention of long-playing records, Tosca recordings were dominated by Maria Callas. In 1953, with conductor Victor de Sabata and the La Scala forces, she made the recording for EMI which for decades has been considered the best of all the recorded performances of the opera.[101][102] She recorded the role again for EMI in stereo in 1964. A number of Callas's live stage performances of Tosca were also preserved. The earliest were two performances in Mexico City, in 1950 and 1952, and the last was in London in 1965.[55] The first stereo recording of the opera was made in 1957 by RCA Victor. Erich Leinsdorf conducted the Rome Opera House orchestra and chorus with Zinka Milanov as Tosca, Jussi Björling as Cavaradossi and Leonard Warren as Scarpia.[103] Herbert von Karajan's acclaimed performance with the Vienna State Opera was in 1963, with Leontyne Price, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Giuseppe Taddei in the leading roles.[101]

The 1970s and 1980s saw a proliferation of Tosca recordings of both studio and live performances. Plácido Domingo made his first recording of Cavaradossi for RCA in 1972, and he continued to record other versions at regular intervals until 1994. In 1976, he was joined by his son, Plácido Domingo Jr., who sang the shepherd boy's song in a filmed version with the New Philharmonia Orchestra. More recent commended recordings have included Antonio Pappano's 2000 Royal Opera House version with Angela Gheorghiu, Roberto Alagna and Ruggero Raimondi.[101] Recordings of Tosca in languages other than Italian are rare but not unknown; over the years versions in French, German, Spanish, Hungarian and Russian have been issued.[98] An admired English language version was released in 1995 in which David Parry led the Philharmonia Orchestra and a largely British cast.[104] Since the late 1990s numerous video recordings of the opera have been issued on DVD and Blu-ray disc (BD). These include recent productions and remastered versions of historic performances.[105]

Editions and amendments

The orchestral score of Tosca was published in late 1899 by Casa Ricordi. Despite some dissatisfaction expressed by Ricordi concerning the final act, the score remained relatively unchanged in the 1909 edition.[106] An unamended edition was published by Dover Press in 1991.[107]

The 1909 score contains a number of minor changes from the autograph score. Some are changes of phrase: Cavaradossi's reply to the sacristan when he asks if the painter is doing penance is changed from "Pranzai"[108] ("I have eaten.") to "Fame non ho" ("I am not hungry."), which William Ashbrook states, in his study of Puccini's operas, accentuates the class distinction between the two. When Tosca comforts Cavaradossi after the torture scene, she now tells him, "Ma il giusto Iddio lo punirá" ("But a just God will punish him" [Scarpia]); formerly she stated, "Ma il sozzo sbirro lo pagherà" ("But the filthy cop will pay for it."). Other changes are in the music; when Tosca demands the price for Cavaradossi's freedom ("Il prezzo!"), her music is changed to eliminate an octave leap, allowing her more opportunity to express her contempt and loathing of Scarpia in a passage which is now near the middle of the soprano vocal range.[109] A remnant of a "Latin Hymn" sung by Tosca and Cavaradossi in act 3 survived into the first published score and libretto, but is not in later versions.[110] According to Ashbrook, the most surprising change is where, after Tosca discovers the truth about the "mock" execution and exclaims "Finire così? Finire così?" ("To end like this? To end like this?"), she was to sing a five-bar fragment to the melody of "E lucevan le stelle". Ashbrook applauds Puccini for deleting the section from a point in the work where delay is almost unendurable as events rush to their conclusion, but points out that the orchestra's recalling "E lucevan le stelle" in the final notes would seem less incongruous if it was meant to underscore Tosca's and Cavaradossi's love for each other, rather than being simply a melody which Tosca never hears.[111]

References

Notes

- Kerman, p. 205

- Walsh, Stephen. "Tosca, Longborough Festival". theartsdesk.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Tommasini 2018, p. 370.

- Nicassio, p. 11

- Nicassio, pp. 12–13

- Budden, p. 181

- Fisher, p. 21

- Phillips-Matz, pp. 106–107

- Phillips-Matz, pp. 107–108

- Phillips-Matz, p. 109

- Budden, pp. 182–183

- Nicassio, p. 17

- Phillips-Matz, p. 18

- "Tosca: Performance history". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Osborne, p. 115

- Fisher, p. 31

- Burton et al., p. 86

- Nicassio, pp. 32–34

- Nicassio, p. 35

- Nicassio, p. 46

- Nicassio, pp. 48–49

- Nicassio, pp. 169–170

- Nicassio, p. 47

- Nicassio, pp. 204–205

- Nicassio, p. 18

- Phillips-Matz, p. 112

- Nicassio, pp. 272–274

- Nicassio, p. 227

- Fisher, p. 23

- Budden, p. 185

- Budden, p. 189

- Phillips-Matz, p. 115

- Fisher, p. 20

- Burton et al., p. 278

- Nicassio, p. 306

- Osborne, p. 139

- Budden, p. 194

- Budden, pp. 194–195

- Budden, p. 195

- Phillips-Matz, p. 116

- Budden, p. 197

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Tosca, 14 January 1900". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Phillips-Matz, p. 118

- Budden, p. 198

- Ashbrook, p. 77

- Greenfeld, pp. 122–123

- Budden, p. 199

- Phillips-Matz, p. 120

- Budden, p. 225

- Greenfeld, pp. 138–139

- "Emmy Destinn (1878–1930)". The Kapralova Society. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Neef, pp. 462–467

- Phillips-Matz, p. 121

- Petsalēs-Diomēdēs, pp. 291–293

- Hamilton, Frank (2009). "Maria Callas: Performance Annals and Discography" (PDF). frankhamilton.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Girardi, pp. 192–193

- "Tosca, Bregenzer Festspiele – Seebühne". The Financial Times. 30 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- O'Connor, John J. (1 January 1993). "A Tosca performed on actual location". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- Forbes, Elizabeth (7 September 2007). "Luciano Pavarotti (Obituary)". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Nicassio, pp. 241–242

- Valetta (1900). "Rassegna Musicale". Nuova Antologia. 85 of 169.

- Phillips-Matz, p. 119

- Greenfeld, pp. 125–126

- "The Royal Opera: Puccini's opera La Tosca". The Musical Times. London: 536–537. 1 August 1900.

- Carner, p. 468

- Newman, pp. 188, 230–231

- Newman, p. 465

- Budden, p. 222

- Osborne, p. 143

- "Statistics 2013/14", Operabase

- Greenfield, pp. 148–150

- Fisher, pp. 27–28

- Osborne, pp. 137–138

- Budden, Julian. "Tosca". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 28 June 2010. (subscription required)

- Fisher, pp. 33–35

- Burton et al., p. 201

- Newman. p. 114

- Budden, p. 203

- Budden, p. 207

- Newman, p. 191

- Newman, p. 221

- Newman, p. 235

- Burton et al., pp. 130–131

- Budden, p. 212

- Newman, pp. 233–234

- Osborne, pp. 140–143

- Greenfield, p. 136

- Budden, p. 216

- Newman, p. 244

- In the first edition the line was recited later, on the D♯ before rehearsal 65. See Appendix 2g (Ricordi 1995, p. LXIV)

- Newman, p. 245

- Budden, p. 217

- Fisher, p. 26

- Ashbrook, p. 82

- Newman, p. 150

- Nicassio, pp. 253–254

- Giacomo Puccini (1992). Tosca in Full Score. Dover Music Scores (reprint ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486269375.

- "There are 250 recordings of Tosca by Giacomo Puccini on file". Operadis. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- Gaisberg, F. W. (June 1944). "The Recording of Tosca". Gramophone. London. p. 15. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2010.(subscription required)

- "Complete Recordings of Two Puccini Operas: Tosca and Turandot". Gramophone. London. December 1938. p. 23. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2010.(subscription required)

- Roberts, pp. 761–762

- Greenfield et al., pp. 314–318

- Hope-Wallace, Philip (February 1960). "Puccini: Tosca complete". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 71. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2010.(subscription required)

- "Puccini: Tosca (Sung in English)". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. June 1996. p. 82. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2010.(subscription required)

- "DVD videos, Puccini's Tosca". Presto Classical. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- "Tosca". University of Rochester. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Tosca in Full Score. Dover Publications. 1992. ISBN 0-486-26937-X.

- Tosca, revised vocal score by Roger Parker (Ricordi 1995), critical notes on p. XL

- Ashbrook, pp. 92–93

- Nicassio, p. 245

- Ashbrook, p. 93

Sources

- Ashbrook, William (1985). The Operas of Puccini. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9309-6.

tosca cast bells.

- Budden, Julian (2002). Puccini: His Life and Works (paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816468-8.

- Burton, Deborah; Nicassio, Susan Vandiver; Züno, Agostino, eds. (2004). Tosca's Prism: Three Moments of Western Cultural History. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-616-9.

- Carner, Mosco (1958). Puccini: A Critical Biography. Gerald Duckworth.

- Fisher, Burton D., ed. (2005). Opera Classics Library Presents Tosca (revised ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Opera Journeys Publishing. ISBN 978-1-930841-41-3.

- Girardi, Michele (2000). Puccini: His International Art. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 978-0-226-29757-6.

- Greenfeld, Howard (1980). Puccini. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7091-9368-5.

- Greenfield, Edward (1958). Puccini: Keeper of the Seal. London: Arrow Books.

- Greenfield, Edward; March, Ivan; Layton, Robert, eds. (1993). The Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-046957-8.

- Kerman, Joseph (2005). Opera as Drama. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24692-8. (Note: this book was first published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1956)

- Neef, Sigrid, ed. (2000). Opera: Composers, Works, Performers (English ed.). Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 978-3-8290-3571-2.

- Newman, Ernest (1954). More Opera Nights. London: Putnam.

- Nicassio, Susan Vandiver (2002). Tosca's Rome: The Play and the Opera in Historical Context (paperback ed.). Oxford: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517974-3.

- Osborne, Charles (1990). The Complete Operas of Puccini. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-04868-3.

- Petsalēs-Diomēdēs, N. (2001). The Unknown Callas: The Greek Years. Cleckheaton (UK): Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-059-2.

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (2002). Puccini: A Biography. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-530-8.

- Roberts, David, ed. (2005). The Classic Good CD & DVD Guide 2006. London: Haymarket. ISBN 978-0-86024-972-6.

- Tommasini, Anthony (2018). The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide. Penguin. p. 370. ISBN 9780698150133.

Further reading

- Gruber, Paul, ed. (2003). The Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03444-8.

- Franco Zeffirelli; John Tooley (interviews by Anna Tims), "How we made: Franco Zeffirelli and John Tooley on Tosca (1964)". The Guardian (London), 23 July 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

External links

- Tosca: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto

- Full piano score with notes

- Susan Vandiver Nicassio: "Ten Things You Didn't Know about Tosca", University of Chicago Press