Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (Spanish: Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic,[1] is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 February 1848, in the Villa de Guadalupe Hidalgo (now a neighborhood of Mexico City) between the United States and Mexico that ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The treaty was ratified by the United States on 10 March and by Mexico on 19 May. The ratifications were exchanged on 30 May, and the treaty was proclaimed on 4 July 1848.[2]

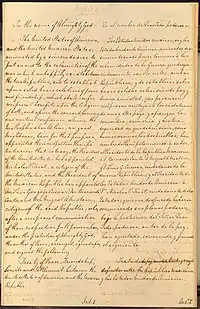

| Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the Republic of Mexico | |

|---|---|

Cover of the exchange copy of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo | |

| Signed | 2 February 1848 |

| Location | Guadalupe Hidalgo |

| Effective | 30 May 1848 |

| Negotiators | List

|

| Signatories |

|

| Citations | 9 Stat. 922; TS 207; 9 Bevans 791 |

| See also the military convention of 29 February 1848 (5 Miller 407; 9 Bevans 807). | |

| Part of a series on |

| Chicanos and Mexican Americans |

|---|

|

With the defeat of its army and the fall of its capital in September 1847, Mexico entered into negotiations with the U.S. peace envoy, Nicholas Trist, to end the war. On the Mexican side, there were factions that did not concede defeat or seek to engage in negotiations. The treaty called for the United States to pay US$15 million to Mexico and to pay off the claims of American citizens against Mexico up to US$5 million. It gave the United States the Rio Grande as a boundary for Texas, and gave the U.S. ownership of California, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado, as well as an area comprising most of New Mexico, and approximately two-thirds of Arizona. Mexicans in those annexed areas had the choice of relocating within Mexico's new boundaries or receiving American citizenship with full civil rights.

The U.S. Senate advised and consented to ratification of the treaty by a vote of 38–14. The opponents of this treaty were led by the Whigs, who had opposed the war and rejected manifest destiny in general, and rejected this expansion in particular. The amount of land gained by the United States from Mexico was further increased as a result of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, which ceded parts of present-day southern Arizona and New Mexico to the United States.

Negotiators

The peace talks were negotiated by Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the US State Department, who had accompanied General Winfield Scott as a diplomat and President James K. Polk's representative. Trist and General Scott, after two previous unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a treaty with General José Joaquín de Herrera, determined that the only way to deal with Mexico was as a conquered enemy. Trist negotiated with a special commission representing the collapsed government led by Don José Bernardo Couto, Don Miguel de Atristain, and Don Luis Gonzaga Cuevas of Mexico.[3]

Terms

Although Mexico ceded Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México, the text of the treaty[4] did not list territories to be ceded, and avoided the disputed issues that were causes of war: the validity of the 1836 revolution that established the Republic of Texas, Texas's boundary claims as far as the Rio Grande, and the right of the Republic of Texas to arrange the 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States.

Instead, Article V of the treaty simply described the new U.S.–Mexico border. From east to west, the border consisted of the Rio Grande northwest from its mouth to the point where it strikes the southern boundary of New Mexico (roughly 32 degrees north), as shown in the Disturnell map, then due west from this point to the 110th meridian west, then north along the 110th Meridian to the Gila River and down the river to its mouth. Unlike the New Mexico segment of the boundary, which depended partly on unknown geography, "in order to preclude all difficulty in tracing upon the ground the limit separating Upper from Lower California", a straight line was drawn from the mouth of the Gila to one marine league south of the southernmost point of the port of San Diego, slightly north of the previous Mexican provincial boundary at Playas de Rosarito.

Comparing the boundary in the Adams–Onís Treaty to the Guadalupe Hidalgo boundary, Mexico conceded about 55% of its pre-war, pre-Texas territorial claims[5] and now has an area of 1,972,550 km² (761,606 sq mi).

In the United States, the 1.36 million km² (525,000 square miles) of the area between the Adams-Onis and Guadalupe Hidalgo boundaries outside the 1,007,935 km2 (389,166 sq mi) claimed by the Republic of Texas is known as the Mexican Cession. That is to say, the Mexican Cession is construed not to include any territory east of the Rio Grande, while the territorial claims of the Republic of Texas included no territory west of the Rio Grande. The Mexican Cession included essentially the entirety of the former Mexican territory of Alta California, but only the western portion of Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico, and includes all of present-day California, Nevada and Utah, most of Arizona, and western portions of New Mexico and Colorado.

Articles VIII and IX ensured safety of existing property rights of Mexican citizens living in the transferred territories. Despite assurances to the contrary, the property rights of Mexican citizens were often not honored by the U.S. in accordance with modifications to and interpretations of the Treaty.[6][7][8] The U.S. also agreed to assume $3.25 million (equivalent to $101.8 million today) in debts that Mexico owed to United States citizens.

The residents had one year to choose whether they wanted American or Mexican citizenship; Over 90% chose American citizenship. The others moved to what remained of Mexico (where they received land), or in some cases in New Mexico were allowed to remain in place as Mexican citizens.[9][10]

Article XII engaged the United States to pay, "In consideration of the extension acquired", 15 million dollars (equivalent to $470 million today),[11] in annual installments of 3 million dollars.

Article XI of the treaty was important to Mexico. It provided that the United States would prevent and punish raids by Indians into Mexico, prohibited Americans from acquiring property, including livestock, taken by the Indians in those raids, and stated that the U.S. would return captives of the Indians to Mexico. Mexicans believed that the United States had encouraged and assisted the Comanche and Apache raids that had devastated northern Mexico in the years before the war. This article promised relief to them.[12]

Article XI, however, proved unenforceable. Destructive Indian raids continued despite a heavy U.S. presence near the Mexican border. Mexico filed 366 claims with the U.S. government for damages done by Comanche and Apache raids between 1848 and 1853.[13] In 1853, in the Treaty of Mesilla concluding the Gadsden Purchase, Article XI was annulled.[14]

Results

The land that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought into the United States became, between 1850 and 1912, all or part of ten states: California (1850), Nevada (1864), Utah (1896), and Arizona (1912), as well as, depending upon interpretation, the entire state of Texas (1845), which then included part of Kansas (1861); Colorado (1876); Oklahoma (1907); and New Mexico (1912). The area of domain acquired was given by the Federal Interagency Committee as 338,680,960 acres.[15] The cost was $16,295,149 or approximately 5 cents an acre.[15] The remainder (the southern parts) of New Mexico and Arizona were peacefully purchased under the Gadsden Purchase, which was carried out in 1853. In this purchase the United States paid an additional $10 million (equivalent to $250 million in 2020), for land intended to accommodate a transcontinental railroad. However, the American Civil War delayed construction of such a route, and it was not until 1881 that the Southern Pacific Railroad finally was completed as a second transcontinental railroad, fulfilling the purpose of the acquisition.[16]

Background to the war

Mexico had claimed the area in question since winning its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821 following the Mexican War of Independence. The Spanish had conquered part of the area from the American Indian tribes over the preceding three centuries, but there remained powerful and independent indigenous nations within that northern region of Mexico. Most of that land was too dry (low rainfall) and too mountainous to support many people, until the advent of new technology after about 1880: means for damming and distributing water from the few rivers to irrigated farmland; the telegraph; the railroad; the telephone; and electrical power.

About 80,000 Mexicans inhabited California, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas during the period 1845 to 1850, with far fewer in Nevada, southern and western Colorado, and Utah.[17] On 1 March 1845, U.S. President John Tyler signed legislation to authorize the United States to annex the Republic of Texas, effective on 29 December 1845. The Mexican government, which had never recognized the Republic of Texas as an independent country, had warned that annexation would be viewed as an act of war. The United Kingdom and France, both of which recognized the independence of the Republic of Texas, repeatedly tried to dissuade Mexico from declaring war against its northern neighbor. British efforts to mediate the quandary proved fruitless, in part because additional political disputes (particularly the Oregon boundary dispute) arose between Great Britain (as the claimant of modern Canada) and the United States.

On 10 November 1845, before the outbreak of hostilities, President James K. Polk sent his envoy, John Slidell, to Mexico. Slidell had instructions to offer Mexico around $5 million for the territory of Nuevo México and up to $40 million for Alta California.[18] The Mexican government dismissed Slidell, refusing to even meet with him.[19] Earlier in that year, Mexico had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States, based partly on its interpretation of the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, under which newly independent Mexico claimed it had inherited rights. In that agreement, the United States had "renounced forever" all claims to Spanish territory.[20][21]

Neither side took any further action to avoid a war. Meanwhile, Polk settled a major territorial dispute with Britain via the Oregon Treaty, which was signed on 15 June 1846. By avoiding any chance of conflict with Great Britain, the U.S was given a free hand in regard to Mexico. After the Thornton Affair of 25–26 April, when Mexican forces attacked an American unit in the disputed area, with the result that 11 Americans were killed, five wounded and 49 captured, Congress passed a declaration of war, which Polk signed on 13 May 1846. The Mexican Congress responded with its own war declaration on 23 April 1846. [22]

Conduct of war

U.S. forces moved quickly far beyond Texas to conquer Alta California and New Mexico. Fighting there ended on 13 January 1847 with the signing of the "Capitulation Agreement" at "Campo de Cahuenga" and end of the Taos Revolt.[23] By the middle of September 1847, U.S. forces had successfully invaded central Mexico and occupied Mexico City.

Peace negotiations

Some Eastern Democrats called for complete annexation of Mexico and recalled that a group of Mexico’s leading citizens had invited General Winfield Scott to become dictator of Mexico after his capture of Mexico City (he declined). [24] However, the movement did not draw widespread support. President Polk's State of the Union address in December 1847 upheld Mexican independence and argued at length that occupation and any further military operations in Mexico were aimed at securing a treaty ceding California and New Mexico up to approximately the 32nd parallel north and possibly Baja California and transit rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[19]

Despite its lengthy string of military defeats, the Mexican government was reluctant to agree to the loss of California and New Mexico. Even with its capital under enemy occupation, the Mexican government was inclined to consider factors such as the unwillingness of the U.S. administration to annex Mexico outright and what appeared to be deep divisions in domestic U.S. opinion regarding the war and its aims, which caused it to imagine that it was actually in a far better negotiating position than the military situation might have suggested. A further consideration was the growing opposition to slavery that had caused Mexico to end formal slavery in 1829, and its awareness of the well-known and growing sectional divide in the U.S. over the issue of slavery. It therefore made sense for Mexico to negotiate with a goal of playing Northern U.S. interests against Southern U.S. interests.

The Mexicans proposed peace terms that offered only sale of Alta California north of the 37th parallel north — north of Santa Cruz, California and Madera, California and the southern boundaries of today's Utah and Colorado. This territory was already dominated by Anglo-American settlers, but perhaps more importantly from the Mexican point of view, it represented the bulk of pre-war Mexican territory north of the Missouri Compromise line of parallel 36°30′ north — lands that, if annexed by the U.S., would have been presumed by Northerners to be forever free of slavery. The Mexicans also offered to recognize the freedom of Texas from Mexican rule and its right to join the Union, but held to its demand of the Nueces River as a boundary.

While the Mexican government could not reasonably have expected the Polk Administration to accept such terms, it would have had reason to hope that a rejection of peace terms so favorable to Northern interests might have the potential to provoke sectional conflict in the United States, or perhaps even a civil war that would fatally undermine the U.S. military position in Mexico. Instead, these terms combined with other Mexican demands (in particular, for various indemnities) only provoked widespread indignation throughout the U.S. without causing the sectional conflict the Mexicans were hoping for.

Jefferson Davis advised Polk that if Mexico appointed commissioners to come to the U.S., the government that appointed them would probably be overthrown before they completed their mission, and they would likely be shot as traitors on their return; so that the only hope of peace was to have a U.S. representative in Mexico.[25] Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the State Department under President Polk, finally negotiated a treaty with the Mexican delegation after ignoring his recall by President Polk in frustration with failure to secure a treaty.[26] Notwithstanding that the treaty had been negotiated against his instructions, given its achievement of the major American aim, President Polk passed it on to the Senate.[26]

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed by Nicholas Trist (on behalf of the U.S.) and Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto and Miguel Atristain as plenipotentiary representatives of Mexico on 2 February 1848, at the main altar of the old Basilica of Guadalupe at Villa Hidalgo (within the present city limits) as U.S. troops under the command of Gen. Winfield Scott were occupying Mexico City.[27]

Changes to the treaty and ratification

The version of the treaty ratified by the United States Senate eliminated Article X,[28] which stated that the U.S. government would honor and guarantee all land grants awarded in lands ceded to the U.S. to citizens of Spain and Mexico by those respective governments. Article VIII guaranteed that Mexicans who remained more than one year in the ceded lands would automatically become full-fledged United States citizens (or they could declare their intention of remaining Mexican citizens); however, the Senate modified Article IX, changing the first paragraph and excluding the last two. Among the changes was that Mexican citizens would "be admitted at the proper time (to be judged of by the Congress of the United States)" instead of "admitted as soon as possible", as negotiated between Trist and the Mexican delegation.

An amendment by Jefferson Davis giving the U.S. most of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León, all of Coahuila and a large part of Chihuahua was supported by both senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party, Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray Mason of Virginia and Ambrose Hundley Sevier were opposed and the amendment was defeated 44–11.[29]

An amendment by Whig Sen. George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico and California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats. Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding votes for acquiring the new territories.

A motion to insert into the treaty the Wilmot Proviso (banning slavery from the acquired territories) failed 15–38 on sectional lines.

The treaty was leaked to John Nugent before the U.S. Senate could approve it. Nugent published his article in the New York Herald and, afterward, was questioned by senators. He was detained in a Senate committee room for one month, though he continued to file articles for his newspaper and ate and slept at the home of the sergeant of arms. Nugent did not reveal his source, and senators eventually gave up their efforts.[30]

The treaty was subsequently ratified by the U.S. Senate by a vote of 38 to 14 on 10 March 1848 and by Mexico through a legislative vote of 51 to 34 and a Senate vote of 33 to 4, on 19 May 1848. News that New Mexico's legislative assembly had just passed an act for organization of a U.S. territorial government helped ease Mexican concern about abandoning the people of New Mexico.[31] The treaty was formally proclaimed on 4 July 1848.[32]

Protocol of Querétaro

On 30 May 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further negotiated a three-article protocol to explain the amendments. The first article stated that the original Article IX of the treaty, although replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy of land grants pursuant to Mexican law.[33]

The protocol further noted that said explanations had been accepted by the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs on behalf of the Mexican Government,[33] and was signed in Querétaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford and Luis de la Rosa.

The U.S. would later go on to ignore the protocol on the grounds that the U.S. representatives had over-reached their authority in agreeing to it.[34]

Treaty of Mesilla

The Treaty of Mesilla, which concluded the Gadsden purchase of 1854, had significant implications for the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article II of the treaty annulled article XI of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and article IV further annulled articles VI and VII of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article V however reaffirmed the property guarantees of Guadalupe Hidalgo, specifically those contained within articles VIII and IX.[35]

Effects

In addition to the sale of land, the treaty also provided for the recognition of the Rio Grande as the boundary between the state of Texas and Mexico.[36] The land boundaries were established by a survey team of appointed Mexican and American representatives,[26] and published in three volumes as The United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. On 30 December 1853, the countries by agreement altered the border from the initial one by increasing the number of border markers from 6 to 53.[26] Most of these markers were simply piles of stones.[26] Two later conventions, in 1882 and 1889, further clarified the boundaries, as some of the markers had been moved or destroyed.[26] Photographers were brought in to document the location of the markers. These photographs are in Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief Engineers, in the National Archives.

The southern border of California was designated as a line from the junction of the Colorado and Gila rivers westward to the Pacific Ocean, so that it passes one Spanish league south of the southernmost portion of San Diego Bay. This was done to ensure that the United States received San Diego and its excellent natural harbor, without relying on potentially inaccurate designations by latitude.

The treaty extended the choice of U.S. citizenship to Mexicans in the newly purchased territories, before many African Americans, Asians and Native Americans were eligible. If they chose to, they had to declare to the U.S. government within a year the Treaty was signed; otherwise, they could remain Mexican citizens, but they would have to relocate.[5] Between 1850 and 1920, the U.S. Census counted most Mexicans as racially "white".[37] Nonetheless, racially tinged tensions persisted in the era following annexation, reflected in such things as the Greaser Act in California, as tens of thousands of Mexican nationals suddenly found themselves living within the borders of the United States. Mexican communities remained segregated de facto from and also within other U.S. communities, continuing through the Mexican migration right up to the end of the 20th century throughout the Southwest.

Community property rights in California are based on Roman Catholic doctrine regarding marriage, and are a legacy of the Mexican era. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that the property rights of Mexican subjects would be kept inviolate. The early Californians felt compelled to continue the community property system regarding the earnings and accumulation of property during a marriage, and it became incorporated into the California Constitution.[38]

Land gained by the United States

)_1848_UTA.jpg.webp)

The US received the territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. Today they comprise some or all of the U.S. states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming from the treaty.

Additional issues

Disputes about whether to make all this new territory into free states or slave states contributed heavily to the rise in North–South tensions that led to the American Civil War just over a decade later.

Border disputes continued. Mexico's economic problems persisted,[39] leading to the controversial Gadsden Purchase in 1854, intended to rectify an error in the original treaty, but led to Mexico demanding a large sum of money for the revision, which was paid. There was also William Walker's short-lived Republic of Lower California filibustering incident in that same year. The Channel Islands of California and Farallon Islands are not mentioned in the Treaty.[40]

The border was routinely crossed by the armed forces of both countries. Mexican and Confederate troops often clashed during the American Civil War, and the U.S. crossed the border during the war of French intervention in Mexico. In March 1916 Pancho Villa led a raid on the U.S. border town of Columbus, New Mexico, which was followed by the Pershing expedition. The shifting of the Rio Grande since the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe caused a dispute over the boundary between the states of New Mexico and Texas, a case referred to as the Country Club Dispute that was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927.[41] Controversy over community land grant claims in New Mexico persists to this day.[42]

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo led to the establishment in 1889 of the International Boundary and Water Commission to maintain the border, and pursuant to newer treaties to allocate river waters between the two nations, and to provide for flood control and water sanitation. Once viewed as a model of international cooperation, in recent decades the IBWC has been heavily criticized as an institutional anachronism, by-passed by modern social, environmental, and political issues.[43]

Writing many years later, Nicholas Trist would describe the treaty as "a thing for every right-minded American to be ashamed of".[44]

See also

- Gadsden Purchase

- Treaty of Cahuenga

- United States and Mexican Boundary Survey

- 1848 in Mexico

- Annexation Bill of 1866

- Reconquista (Mexico)

- United States Court of Private Land Claims

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (History of New Mexico)

- Californios in literature

- Botiller v. Dominguez

- Zimmermann Telegram

- Aboriginal title

- Aboriginal title in California

- Aboriginal title in New Mexico

References

- "Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo [Exchange copy]". NATIONAL ARCHIVES CATALOG. US National Archives. 2 February 1848. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Avalon Project – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Defiant Peacemker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War, by author Wallace Ohrt

- "Avalon Project – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- U.S. Congress. Recommendation of the Public Land Commission for Legislation as to Private Land Claims, 46th Congress, 2nd Session, 1880, House Executive Document 46, pp. 1116–17.

- Gonzales, Manuel G. (2009). Mexicanos: A history of Mexicans in the United States (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-253-33520-3.

- Davenport (2005), p. 48.

- Noel, Linda C. (2011). "'I am an American': Anglos, Mexicans, Nativos, and the National Debate over Arizona and New Mexico Statehood". Pacific Historical Review. 80 (3): 430–467 [at p. 436]. doi:10.1525/phr.2011.80.3.430.

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard (1990). "Citizenship and Property Rights: U.S. Interpretations of the Treaty". The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 62-86. ISBN 0-8061-2240-4.

- "Error -- File Not Found (Hispanic Reading Room, Hispanic Division, Area Studies)". loc.gov.

- Delay, Brian (2007). "Independent Indians and the U.S. Mexican War". The American Historical Review. 112 (1): 67. doi:10.1086/ahr.112.1.35.

- Schmal, John P. "Sonora: Four Centuries of Indigenous Resistance". Houston Institute of Culture. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Kluger, Richard (2007). Seizing Destiny: How America Grew From Sea to Shining Sea. New York: Knopf. pp. 493–494. ISBN 978-0-375-41341-4.

- Our Public Lands. Issued quarterly by UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT. 1 January 1958. p. 7.

- Devine, David (2004). Slavery, Scandal, and Steel Rails: The 1854 Gadsden Purchase and the Building of the Second Transcontinental Railroad Across Arizona and New Mexico Twenty-Five Years Later. New York: iUniverse. ISBN 0-595-32913-6.

- Nostrand, Richard L. (1975). "Mexican Americans Circa 1850". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 65 (3): 378–390. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1975.tb01046.x.

- Mills, B. 2003. U.S.-Mexican War. Facts On File, p. 23. ISBN 0-8160-4932-7

- "James K. Polk's Third Annual Message, 7 December 1847". presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- Adams-Onis Treaty, Article III. Archived 19 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine From: yale.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- "The United States hereby cede to His Catholic Majesty, and renounce forever, all their rights, claims, and pretensions to the Territories lying West and South of the above described Line [...]. http://www.tamu.edu/faculty/ccbn/dewitt/adamonis.htm

- Davenport (2005), p. 39.

- Original Capitulation Agreement document (one of 25) on view at Campo de Cahuenga historical site

- "Mexican Argument for Annexation." The Living Age, Volume 10, Issue 123. 19 September 1846.

- Rives 1913, p. 622.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. National Archives. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- "The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". Hispanic Reading Room. Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

The Library holds the copy of the Treaty found in Nicholas Trist’s papers, and as such, it does not represent the final version of the document which is kept at the U.S. National Archives.

- "The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo." Library of Congress, Hispanic Reading Room. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- George Lockhart Rives (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 634–636.

- "The Senate Arrests a Reporter". U.S. Senate.

- Rives 1913, p. 649.

- Online Highways LLC editorial group. "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". U-S-History.com. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Treaty of Hidalgo, Protocol of Querétaro. From: academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- David Hunter Miller, Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America, vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937)

- Mills, B. p. 122.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Article V. From: academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- Gibson, C.J. and E. Lennon. 1999. "Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1850–1990." U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- Cali. Const. art. XX, § 7.

- Davenport (2005), p. 60.

- Barnard R. Thompson. "Mexico's Claim to California Islands – A Never-ending Story".

- Bowden, J. J. (1959). "The Texas-New Mexico Boundary Dispute along the Rio Grande". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 63 (2): 221–237. JSTOR 30240862.

- "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: Findings and Possible Options Regarding Longstanding Community Land Grant Claims in New Mexico" (PDF). General Accounting Office. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- Robert J. McCarthy, Executive Authority, Adaptive Treaty Interpretation, and the International Boundary and Water Commission, U.S.-Mexico, 14-2 U. Denv. Water L. Rev. 197(Spring 2011) (also available for free download at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1839903).

- Morgan, Robert (21 August 2012). Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion. North Carolina: Algonquin Books. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-61620-189-0.

Sources

- Davenport, John C. (2005). The U.S.-Mexico Border : The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Philadelphia: Chelsea House. ISBN 0-7910-7833-7.

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard (1990), The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2240-4

- Ohrt, Wallace (1997), Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-778-4

- Reeves, Jesse S. (1905), "The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo" (PDF), American Historical Review, 10 (2): 309–324, doi:10.2307/1834723, hdl:10217/189496, JSTOR 1834723

- Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States. Vol. 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

External links

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and related resources at the U.S. Library of Congress

- Library of Congress – Hispanic Reading Room portal, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

- Text of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

- Copy of Treaty, including sections stricken out by Senate

- Text of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and anaysis

- U.S. General Accounting Office report on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, June 2004

- Library of Congress Guide to the Mexican War

- Time magazine article on the treaty leak

- Occupation and Aftermath at A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington

- Map of North America and the Caribbean at the time of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at omniatlas.com