USS Washington (BB-56)

USS Washington (BB-56) was the second and final member of the North Carolina class of fast battleships, the first vessel of the type built for the United States Navy. Built under the Washington Treaty system, North Carolina's design was limited in displacement and armament, though the United States used a clause in the Second London Naval Treaty to increase the main battery from the original armament of nine 14 in (356 mm) guns to nine 16 in (406 mm) guns. The ship was laid down in 1938 and completed in May 1941, while the United States was still neutral during World War II. Her initial career was spent training along the East Coast of the United States until after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, bringing the United States into the war.

_in_Puget_Sound%252C_10_September_1945.jpg.webp) Washington in September 1945 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Washington |

| Namesake | State of Washington |

| Builder | Philadelphia Naval Shipyard |

| Laid down | 14 June 1938 |

| Launched | 1 June 1940 |

| Commissioned | 15 May 1941 |

| Decommissioned | 27 June 1947 |

| Stricken | 1 June 1960 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 24 May 1961 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | North Carolina-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 728 ft 9 in (222.1 m) |

| Beam | 108 ft 4 in (33 m) |

| Draft | 32 ft 11.5 in (10 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Range | 17,450 nmi (32,320 km; 20,080 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement | 1,800 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 3 × Vought OS2U Kingfisher floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities | 2 × trainable catapults |

Washington was initially deployed to Britain to reinforce the Home Fleet, which was tasked with protecting convoys carrying supplies to the Soviet Union. She saw no action during this period, as the German fleet remained in port, and Washington was recalled to the US in July 1942 to be refitted and transferred to the Pacific. Immediately sent to the south Pacific to reinforce Allied units fighting the Guadalcanal campaign, the ship became the flagship of Rear Admiral Willis Lee. She saw action at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on the night of 14–15 November in company with the battleship USS South Dakota and four destroyers. After South Dakota inadvertently drew heavy Japanese fire by sailing too closely to Admiral Nobutake Kondō's squadron, Washington took advantage of the Japanese preoccupation with South Dakota to inflict fatal damage on the Japanese battleship Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami, while avoiding damage herself. Washington's attack disrupted Kondō's planned bombardment of U.S. Marine positions on Guadalcanal and forced the remaining Japanese ships to withdraw.

From 1943 onward, she was primarily occupied with screening the fast carrier task force, though she also occasionally shelled Japanese positions in support of the various amphibious assaults. During this period, Washington participated in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign in late 1943 and early 1944, the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign in mid-1944, and the Philippines campaign in late 1944 and early 1945. Operations to capture Iwo Jima and Okinawa followed in 1945, and during the later stages of the Battle of Okinawa, Washington was detached to undergo an overhaul, though by the time it was completed, Japan had surrendered, ending the war. Washington then moved to the east coast of the US, where she was refitted to serve as a troop transport as part of Operation Magic Carpet, carrying a group of over 1,600 soldiers home from Britain. She was thereafter decommissioned in 1947 and assigned to the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, where she remained until 1960 when she was stricken from the naval register and sold for scrap the next year.

Design

The North Carolina class was the first new battleship design built under the Washington Naval Treaty system; her design was bound by the terms of the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936, which added a restriction on her main battery of guns no larger than 14 inches (356 mm). The General Board evaluated a number of designs ranging from traditional 23-knot (43 km/h; 26 mph) battleships akin to the "standard" series or fast battleships, and ultimately a fast battleship armed with twelve 14-inch guns was selected. After the ships were authorized, however, the United States invoked the escalator clause in the treaty that allowed an increase to 16 in (406 mm) guns in the event that any member nation refused to sign the treaty, which Japan refused to do.[1]

Washington was 728 feet 9 inches (222.1 m) long overall and had a beam of 108 ft 4 in (33 m) and a draft of 32 ft 11.5 in (10 m). Her standard displacement amounted to 35,000 long tons (36,000 t) and increased to 44,800 long tons (45,500 t) at full combat load. The ship was powered by four General Electric steam turbines, each driving one propeller shaft, using steam provided by eight oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox boilers. Rated at 121,000 shaft horsepower (90,000 kW), the turbines were intended to give a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 17,450 nautical miles (32,320 km; 20,080 mi) at a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). She carried three Vought OS2U Kingfisher floatplanes for aerial reconnaissance, which were launched by a pair of aircraft catapults on her fantail. Her peace-time crew numbered 1,800 officers and enlisted men, but the crew swelled to 99 officers and 2,035 enlisted during the war.[2][3]

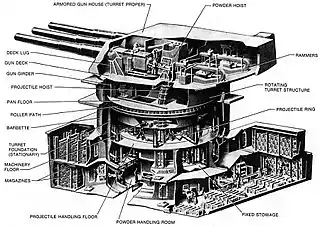

The ship was armed with a main battery of nine 16 in /45 caliber Mark 6 guns[lower-alpha 1] guns in three triple-gun turrets on the centerline, two of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward, with the third aft. The secondary battery consisted of twenty 5 in (127 mm) /38 caliber dual purpose guns mounted in twin turrets clustered amidships, five turrets on either side. As designed, the ship was equipped with an anti-aircraft battery of sixteen 1.1 in (28 mm) guns and eighteen .50-caliber (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns,[lower-alpha 2] but her anti-aircraft battery was expanded greatly during her career.[2][3]

The main armored belt was 12 in (305 mm) thick, while the main armored deck was up to 5.5 in (140 mm) thick. The main battery gun turrets had 16 in (406 mm) thick faces, and they were mounted atop barbettes that were protected with the same thickness of steel. The conning tower had 14.7 in (373 mm) thick sides. The ship's armor layout had been designed with opponents equipped with 14-inch guns in mind, but since the treaty system broke down just before construction began, her design could not be revised to improve the scale of protection to defend against heavier guns. Despite this shortcoming, the North Carolina class proved to be more successful battleships than the better-armored but very cramped South Dakota class.[2]

Modifications

Washington received a number of upgrades over the course of her career, primarily consisting of radar and a new light anti-aircraft battery. The ship received three Mark 3 fire-control radar sets for the main battery, four Mark 4 radars for the secondary guns, a CXAM air-search radar, and an SG surface-search radar. During her early 1944 refit, she received an SK air-search radar in place of the CXAM and a second SG radar; her Mark 3 radars were replaced with more advanced Mark 8 sets, though she retained one of the Mark 3s as a backup. Her Mark 4 radars were later replaced with a combination of Mark 12 and Mark 22 sets. In her final refit in August and September 1945, she had an SK radar forward, an SR air-search set aft, and an SG radar in both positions. A TDY jammer was installed on her forward fire control tower.[4]

Washington's 1.1 in battery was replaced with forty 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors guns in ten quadruple mounts in April 1943, and in August, the number of guns had increased to sixty in fifteen quadruple mounts. Her original light battery of eighteen .50-cal machine guns was decreased to twelve and twenty 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon autocannon in single mounts were installed in early 1942. In June, she had her .50-cal battery increased to twenty-eight barrels, but by September, all were replaced in favor of a uniform battery of forty 20 mm cannon. During the April 1943 refit, her anti-aircraft armament was increased to a total of sixty-four 20 mm cannon. A year later, in April 1944, she lost one of the single mounts in favor of an experimental quadruple 20 mm mount. In November 1944, the ship was slated to have the battery reduced to 48 barrels, but this never happened and instead, in early 1945, she had eight single mounts replaced with eight twin mounts, bringing her final 20 mm battery to seventy-five guns.[5]

Service history

_launching_ceremony%252C_1_June_1940.jpg.webp)

The keel for Washington was laid down on 14 June 1938 at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. Her completed hull was launched on 1 June 1940, and after completing fitting-out work, she was commissioned into the fleet on 15 May 1941.[2] She began builder's sea trials on 3 August, but like her sister ship North Carolina, she suffered from excessive vibration while running at high speed from her original three-bladed screws. Tests with North Carolina produced a workable solution (though the problem was never fully corrected): two four-bladed screws on the outer shafts and two five-bladed propellers on the inboard shafts. Tests continued during her shakedown cruise and subsequent initial training, which were conducted along the East Coast of the United States, as far south as the Gulf of Mexico. She conducted high speed tests in December, during which she failed to reach her designed speed due to the vibration problems.[6]

During this period, the United States was still neutral during World War II. Washington frequently trained with North Carolina and the aircraft carrier Wasp, with Washington serving as the flagship of Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox Jr., the commander of Battleship Division (BatDiv) 6, part of the Atlantic Fleet. Her initial working up training continued into 1942, by which time the country had entered the war as a result of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany's subsequent declaration of war.[7] Modifications to the ship's screws continued as late as February 1942, but these also proved unsuccessful.[8]

Atlantic operations

With the country now at war, Washington was assigned as the flagship of Task Force (TF) 39, still under Wilcox's command, which departed for Britain on 26 March. The unit, which included Wasp and the heavy cruisers Wichita and Tuscaloosa, were to reinforce the British Home Fleet based in Scapa Flow. The Home Fleet had been weakened by the need to detach units, particularly Force H, to take part in the invasion of Madagascar, and the American battle group was needed to help counter the German battleship Tirpitz and other heavy surface units based in occupied Norway.[9][10] The next day, while crossing the Atlantic, Wilcox was swept overboard. Tuscaloosa and a pair of destroyers searched for the admiral, and Wasp sent aircraft aloft to assist the effort, but lookouts on the destroyer Wilson spotted him, face down in the water, having already drowned. The search was called off and the task force continued on to its destination. Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen, aboard Wichita, took command of the unit, which was met at sea by the British cruiser HMS Edinburgh on 3 April. The ships arrived in Scapa Flow two days later, where it came under the command of Admiral John Tovey, the commander of the Home Fleet.[7][11]

._Port_bow%252C_05-29-1941_-_NARA_-_513042.jpg.webp)

For the rest of the month, Washington and the other American ships were occupied with battle practice and familiarization training with the Home Fleet to prepare the different countries' ships for joint operations. TF 39 was redesignated TF 99 in late April, Washington still serving as the flagship. The ships embarked on their first operation on 28 April to conduct a sweep for German warships ahead of the supply convoy PQ 15 to the Soviet Union. The ships of TF 99 operated with elements of the Home Fleet, including the battleship HMS King George V and the carrier Victorious. During the operation, King George V accidentally rammed and sank the destroyer Punjabi; Washington was following too closely to avoid the wreckage, and as she passed over the sinking destroyer, Punjabi's depth charges exploded. The shock from the blast damaged some of Washington's radars and fire-control equipment and caused a small leak in one of her fuel tanks. King George V had to return to port for repairs, but Washington and the rest of TF 99 remained at sea until 5 May. The ships stopped at Hvalfjörður, Iceland, where they took on supplies from the supply ship Mizar.[7][12]

The ships remained in Iceland until 15 May, when they got underway to return to Scapa Flow, arriving there on 3 June. The next day, Admiral Harold Rainsford Stark, the Commander of Naval Forces Europe, visited the ship and made her his temporary headquarters. On 7 June, King George VI came aboard to inspect Washington, and after Stark left she resumed escorting convoys in the Arctic; these included convoys QP 12, PQ 16, and PQ 17.[7] The first two occurred at the same time, with QP 12 returning from the Soviet Union while PQ 16 carrying another load of supplies and weapons. Washington, Victorious, and the battleship Duke of York provided distant support but was not directly engaged by the German U-boats and aircraft that raided PQ 16; QP 12 largely evaded German attention and passed without significant incident.[13]

The PQ 17 operation resulted in disaster when reconnaissance incorrectly reported Tirpitz, the heavy cruisers Admiral Hipper, Admiral Scheer, and Lützow, and nine destroyers to be approaching to attack the convoy, when in reality the Germans were still off the coast of Norway, their progress having been hampered by several of the vessels running aground. The reports of German heavy units at sea prompted the convoy commander to order his ships to scatter, which left them vulnerable to U-boats and Luftwaffe attacks that sank twenty-four of the thirty-five transport ships. While in Hvalfjörður on 14 July, Giffen moved his flag back to Wichita and Washington, escorted by four destroyers, got underway to return to the United States. She arrived in Gravesend Bay on 21 July and moved to the Brooklyn Navy Yard two days later for an overhaul.[7][14]

Guadalcanal campaign

_off_New_York_City%252C_August_1942.jpg.webp)

After completing the refit, Washington got underway on 23 August, bound for the Pacific with an escort of three destroyers. She passed through the Panama Canal on 28 August and arrived in Nukuʻalofa in Tonga on 14 September. There, she became the flagship of Rear Admiral Willis Lee, then the commander of BatDiv 6 and Task Group (TG) 12.2. On 15 September, Washington sailed to meet the ships of TF 17, centered on the carrier Hornet; the ships thereafter operated together and went to Nouméa in New Caledonia to begin operations in support of the campaign in the Solomon Islands. The ships, based out of Nouméa and Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, covered convoys bringing supplies and reinforcements to the marines fighting on Guadalcanal into early November.[7]

During one of these convoy operations in mid-October, Washington, a pair of cruisers, and five destroyers provided distant support but were too far away to take part in the Battle of Cape Esperance on the night of 11–12 October. Shortly thereafter, Washington was transferred to TF 64, the surface combatant force assigned to the Guadalcanal area, still under Lee's command. At this time, the unit also included one heavy and two light cruisers and six destroyers. Over the course of 21–24 October, Japanese land-based reconnaissance aircraft made repeated contacts with TF 64 as a Japanese fleet approached the area, but in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands that began on the 25th, the Japanese concentrated their air attacks on the American carriers of TF 17 and 61. On 27 October, the Japanese submarine I-15 attempted to torpedo Washington but missed.[15]

By early November, the US fleet had been reduced considerably in offensive power; the carriers Wasp and Hornet had been sunk, leaving just the carrier Enterprise, Washington, and the new battleship South Dakota as the only capital ships available to Allied forces fighting in the campaign. Washington joined the other two ships in TF 16, which also included the heavy cruiser Northampton, and nine destroyers. The ships sortied on 11 November to return to the fighting off Guadalcanal. The cruiser Pensacola and two more destroyers joined them the following day. On 13 November, after learning that a major Japanese attack was approaching, Halsey detached South Dakota, Washington, and four of the destroyers as Task Group 16.3, again under Lee's command. Enterprise, her forward elevator damaged from the action at Santa Cruz, was kept to the south as a reserve and to prevent the sole operational American carrier in the Pacific from being lost. The ships of TG 16.3 were to block an anticipated Japanese bombardment group in the waters off Guadalcanal.[16]

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

As Lee's task group approached Guadalcanal, his Japanese counterpart, Admiral Nobutake Kondō steamed to meet him with his main bombardment force, consisting of the fast battleship Kirishima, the heavy cruisers Takao and Atago, and a destroyer screen. While en route, TG 16.3 was re-designated as TF 64 on 14 November; the ships passed to the south of Guadalcanal and then rounded the western end of the island to block Kondō's expected route. Japanese aircraft reported sighting Lee's formation, but identification of the ships ranged from a group of cruisers and destroyers to aircraft carriers, causing confusion among the Japanese commanders. That evening, American reconnaissance aircraft spotted Japanese warships off Savo Island, prompting Lee to order his ships to general quarters. The four destroyers were arrayed ahead of the two battleships.[17] The American task force, having been thrown together a day before, had not operated together as a unit, and both of the battleships had very limited experience shooting their main battery, particularly at night.[18]

At around 23:00 on 14 November, the leading Japanese destroyers in a screening force commanded by Shintarō Hashimoto sent ahead of Kondō's main force spotted Lee's ships and turned about to warn Kondō, while Washington's search radar picked up a Japanese cruiser and a destroyer at about the same time. The ships' fire control radars then began tracking the Japanese vessels and Lee ordered both of his battleships to open fire when ready. Washington fired first with her main battery at 23:17 at a range of 18,000 yd (16,000 m) while her secondary guns fired star shells to illuminate the targets, followed shortly by South Dakota. One of the Japanese destroyers, Ayanami, revealed her position by opening fire on the American destroyer screen, allowing Washington to target her, inflicting serious damage that disabled her propulsion machinery and started a major fire.[19][20]

Shortly thereafter, at about 23:30, an error in the electrical switchboard room knocked out power aboard South Dakota, disabling her radar systems and leaving the ship all but blind to the Japanese vessels approaching the force. By this time, Hashimoto's ships had inflicted serious damage on the American destroyer screen; two of the destroyers were torpedoed (one of which, Benham, survived until the following morning) and a third was destroyed by gunfire. Washington was now left essentially alone to engage the Japanese squadron, though they had yet to actually detect her presence. While Washington's captain, Glenn B. Davis, kept his ship on the disengaged side of the flaming wrecks of the destroyer screen, South Dakota was forced to turn in front of one of the burning destroyers to avoid a collision, which backlit her to the Japanese ships, drawing their fire and allowing Washington to engage them undisturbed.[21][22]

_firing_during_the_Second_Naval_Battle_of_Guadalcanal%252C_14_November_1942.jpg.webp)

At 23:35, Washington's SG radar detected Kondō's main force and tracked them for the next twenty minutes. At 23:58, South Dakota's power was restored and her radar picked up the Japanese ships less than 3 nautical miles (5.6 km; 3.5 mi) ahead. Two minutes later, the leading Japanese ship, Atago, illuminated South Dakota with her search lights and the Japanese line promptly opened fire, scoring twenty-seven hits. Washington, still undetected, opened fire, allocating two of her 5-inch guns to engage Atago and two to fire star shells, while the rest joined her main battery in battering Kirishima at a range of 8,400 yards (7,700 m). Washington scored probably nine 16-inch hits and as many as forty 5-inch hits, inflicting grievous damage. Kirishima was badly holed below the waterline, her forward two turrets were knocked out, and her rudder was jammed, forcing her to steer in a circle to port with an increasing starboard list.[23]

Washington then shifted fire to Atago and Takao, and though straddled the former, failed to score any significant hits; the barrage nevertheless convinced both cruisers to turn off their search lights and reverse course in an attempt to launch torpedoes. At 00:13, the two cruisers fired a spread of sixteen Long Lance torpedoes at Washington, then about 4,000 yards (3,700 m) away, though they all missed. At 00:20, Lee turned his sole surviving combatant (he had ordered the surviving destroyers to disengage earlier in the engagement, and South Dakota's captain, having determined that his ship had been damaged sufficiently to prevent her from taking further action, decided to break off as well) to close with Kondō's cruisers. Atago and Takao briefly engaged with their main batteries and the former launched three more torpedoes, all of which missed. Kondō then ordered the light forces of his reconnaissance screen to make a torpedo attack, but Hashimoto's ships were far out of position and were unable to comply. Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka, who was escorting a supply convoy to Guadalcanal and had thus far not participated in the action, detached two destroyers to aid Kondō. When these ships arrived on the scene, Lee ordered Washington to turn to reverse course at 00:33 to avoid a possible torpedo attack from the destroyers.[24]

Tanaka's two destroyers closed to launch their torpedoes while Washington was disengaging, prompting her to take evasive maneuvers. While withdrawing to the south, Lee kept Washington far west of the damaged American warships so that any Japanese vessels pursuing him would not be drawn onto the damaged vessels. An hour later, Kondō cancelled the bombardment and attempted to contact Kirishima, but after failing to receive a response, sent destroyers to investigate the crippled battleship. She was found burning furiously, still turning slowly to port as progressively worsening flooding disabled her boilers. At 03:25, she capsized and sank; by this time, Ayanami had also been abandoned and sank as a result of the damage inflicted by Washington. By 09:00, Washington had formed back up with South Dakota and the destroyers Benham and Gwin to withdraw from the area. In addition to blocking Kondō's planned bombardment, Lee had delayed Tanaka's convoy late enough that the transports could not unload under cover of darkness, and so they were forced to beach themselves on the island, where they were repeatedly attacked and badly damaged by aircraft from Enterprise and Henderson Field, field artillery, and the destroyer Meade later that morning.[25]

Later operations

.jpg.webp)

Washington returned to screening the carriers of TF 11—Saratoga—and TF 16—Enterprise—while South Dakota departed for repairs. By late November, Lee's command was reinforced by North Carolina, followed later by the battleship Indiana. These battleships were grouped together as TF 64, still under Lee's command, and they covered convoys to support the fighting in the Solomons into the next year. These operations included covering a group of seven transports carrying elements of the 25th Infantry Division to Guadalcanal from 1 to 4 January 1943. During another of these convoy operations later that month, Lee's battleships were too far south to be able to reach the American cruiser force during the Battle of Rennell Island. Washington remained in the south Pacific until 30 April, when she departed Nouméa for Pearl Harbor. On the way, she joined the ships of TF 16. The ships arrived on 8 May.[7][26][27][28]

For the next twenty days, Washington operated as the flagship of TF 60, which conducted combat training off the coast of Hawaii. On 28 May, she went into dry dock at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard for repairs and installation of new equipment.[7] This included a new set of screws that again failed to remediate the vibration problems.[8] Once this work was completed, she resumed training exercises in the area until 27 July, when she got underway with a convoy bound for the south Pacific. For the voyage, she was attached to TG 56.14, and on arriving in the area was detached on 5 August to proceed independently to Havannah Harbor at Efate in the New Hebrides, which she reached two days later. Washington spent the next two months conducting tactical training with the carrier task forces in the Efate area in preparation for upcoming campaigns in the central Pacific.[7]

Now part of TG 53.2, which included three other battleships and six destroyers, Washington got underway on 31 October. The ships met TG 53.3, centered on the carriers Enterprise, Essex, and Independence, the next day, for extensive training exercises that lasted until 5 November. The groups then dispersed and Washington left with escorting destroyers for Viti Levu in the Fiji Islands, which she reached on 7 November.[7]

Gilberts and Marshall Islands campaign

Washington, still Lee's flagship, sortied on 11 November in company with the ships of BatDivs 8 and 9, and four days later they joined TG 50.1, centered on the carrier Yorktown. The fleet proceeded on to the Gilbert Islands, where marines were preparing to land on Tarawa. The carriers of TF 50 launched their strikes on 19 November, continuing into the next day as the marines went ashore on Tarawa and Makin. The attacks continued through 22 November, when the fleet steamed to the north of Makin to patrol the area. On 25 November, the groups of TF 50 were reorganized and Washington was transferred to TG 50.4, along with the carriers Bunker Hill and Monterey and the battleships South Dakota and Alabama.[7]

From 26 to 28 November, the carrier groups operated off Makin to cover the landing of troops and supplies on the island. Japanese aircraft attacked the groups on 27 and 28 November, but they inflicted little damage on the American ships. On 6 December, with the fighting in the Gilberts over, Washington was detached to create TG 50.8 along with North Carolina, South Dakota, Alabama, Indiana, and Massachusetts, covered by Bunker Hill, Monterey, and eleven destroyers. The battleships were sent to bombard the island of Nauru two days later, thereafter returning to Efate on 12 December. The ships remained there only briefly before departing on 25 December for gunnery training with North Carolina and four destroyers. The ships returned to port on 7 January 1944, at which time Washington was assigned to TG 37.2, along with Bunker Hill and Monterey. The ships got underway on 18 January, bound for the next target in the campaign: the Marshall Islands.[7]

The ships stopped briefly in Funafuti in the Ellice Islands on 20 January before departing three days later to meet the rest of what was now TF 58; the unit, which comprised the fast carrier task force, had been created under the command of Rear Admiral Marc Mitscher on 6 January. Washington's unit was accordingly re-numbered as TG 58.1. Having arrived off the main target at Kwajalein by late January, Washington screened the carriers while they conducted extensive strikes on the island and neighboring Taroa. On 30 January, Washington, Massachusetts, and Indiana were detached from the carriers to bombard Kwajalein with an escort of four destroyers. After returning to the carriers the next day, the battleships resumed guard duty while the carriers resumed their air strikes.[7]

While patrolling off the island in the early hours of 1 February, Indiana cut in front of Washington to go refuel a group of destroyers, causing the latter to ram the former and significantly damaging both ships. Washington had some 200 ft (61 m) of bow plating torn from her bow, causing it to collapse.[29] The two vessels withdrew to Majuro for temporary repairs; Washington's crumpled bow was reinforced to allow her to steam to Pearl Harbor on 11 February for further temporary repairs. After arriving there, she was fitted with a temporary bow before continuing on to the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, for permanent repairs.[7] Another new set of screws was installed and in April, Washington conducted vibration tests that revealed a partial solution: the ship could now steam at high speed without significant issues, but vibration was still excessive at speeds between 17 and 20 knots (31 and 37 km/h; 20 and 23 mph).[4] Once the work was completed, the ship joined BatDiv 4 and took on a group of 500 passengers before departing for Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 13 May and disembarked the passengers and proceeding back to the fleet at Majuro. On arrival on 7 June, she resumed her service as now-Vice Admiral Lee's flagship.[7]

Mariana and Palau Islands campaign

Shortly after Washington arrived, the fleet got underway to begin the assault on the Mariana Islands; the carriers struck targets on Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Rota, and Pagan to weaken Japanese defenses before ground forces went ashore. At the time, she was assigned to TG 58.7, which consisted of seven fast battleships, was distributed between the four carrier task groups. On 13 June, Washington and several other battleships were detached to bombard Saipan and Tinian before being relieved by the amphibious force's bombardment group the next day. On 15 June, the fast carrier task force steamed north to hit targets in the Volcano and Bonin Islands, including Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Haha Jima. At the same time, marines stormed the beaches on Saipan; landing was a breach of Japan's inner defensive perimeter that triggered the Japanese fleet to launch a major counter-thrust with the 1st Mobile Fleet, the main carrier strike force.[7][30]

Ozawa's departure was observed by the American submarine Redfin; other submarines, including Flying Fish and Cavalla, tracked the Japanese fleet as it approached, keeping Admiral Raymond Spruance, the Fifth Fleet commander, informed of their movements. As the Japanese fleet approached, Washington and the rest of TF 58 steamed to meet it on 18 June, leading to the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June. Washington and the other battleships, with four cruisers and thirteen destroyers, were deployed some 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) west of the carrier groups to screen the likely path of approach. The Japanese launched their aircraft first, and as they probed the American fleet's defenses, Washington and North Carolina were the first battleships to open fire on the attacking Japanese aircraft. During the action, which was fought primarily by the carriers, the US fleet inflicted serious losses on the Japanese, destroying hundreds of their aircraft and sinking three carriers.[7][31]

With the 1st Mobile Fleet defeated and withdrawing, Washington and the rest of TF 58 returned to the Marianas. She continued to screen the carriers during the Battle of Guam until 25 July, when Washington steamed with the carriers of TG 58.4 to raid the Palau Islands. The attacks lasted until 6 August, when Washington, Indiana, Alabama, the light cruiser Birmingham, and escorting destroyers were detached as TG 58.7 to proceed to Eniwetok. After arriving there on 11 August, the ships refueled and replenished ammunition and other supplies, remaining there for most of the month. On 30 August, the task group got underway with the rest of the fast carrier strike force, which by now had been transferred to Third Fleet command and renumbered TF 38. At this time, Washington was assigned to TG 38.3. The ships sailed first south to the Admiralty Islands and then west, back to the Palaus. There, the carriers began a series of strikes from 6 to 8 September on various targets in the Palaus; Washington contributed her heavy guns to the bombardment of Peleliu and Anguar before the marines assaulted both islands later that month.[7][32]

On 9 and 10 September, task groups 38.1, 38.2, and 38.3 left the Palaus to raid Japanese airfields on Mindanao in the southern Philippines, part of the standard practice to neutralize nearby positions that could interfere with the upcoming assault on the Palaus. Finding few Japanese forces on the island, the carriers shifted north to the Visayas in the central Philippines from 12 to 14 September. The carrier groups then withdrew to refuel at sea before returning to the Philippines to attack airfields on Luzon from 21 and 22 September before making further attacks on installations in the Visayas on 24 September.[32] The carrier groups then proceeded north to make a series of strikes on airfields in Okinawa, Formosa, and Luzon in preparation for the upcoming invasion of the Philippines.[7]

Philippines campaign

TF 38 embarked on the raids to isolate the Philippines and suppress the units of the 1st Air Fleet on 6 October; Washington remained Lee's flagship, attached to TG 38.3. The first operation was a major strike on Japanese air bases on the island of Okinawa on 10 October. The next day, the ships of TG 38.3 refueled at sea before joining the other three task groups for major raids on Formosa that took place from 12 to 14 October. As the fleet withdrew the next day, it defended itself against heavy Japanese air attacks, though the ships of TG 38.3 were not directly engaged as the Japanese attacks concentrated on task groups 38.1 and 38.4. On the 16th, a submarine reported observing a Japanese squadron consisting of three cruisers and eight destroyers searching for damaged Allied warships, and TG 38.3 and TG 38.2 steamed north to catch them, but the aircraft were only able to locate and sink a torpedo boat.[33]

On 17 October, the two task groups withdrew to the south to cover the invasion of Leyte with the rest of TF 38, the same day that elements of Sixth Army went ashore; the raids on Luzon continued into 19 October. By this time, Washington had been reassigned to TG 38.4, screening Enterprise, the fleet carrier Franklin, and the light carriers San Jacinto and Belleau Wood. On 21 October, TG 38.4 withdrew to refuel, during which time they also covered the withdrawal of ships that had been damaged during the Formosa raid, which were still on their way to Ulithi. TG 38.4 was recalled to Leyte the next day.[34]

Battle of Leyte Gulf

The landing on Leyte led to the activation of Operation Shō-Gō 1, the Japanese navy's planned riposte to an Allied landing in the Philippines.[35] The plan was a complicated operation with three separate fleets: The 1st Mobile Fleet, now labeled the Northern Force under Jisaburō Ozawa, the Center Force under Takeo Kurita, and the Southern Force under Shōji Nishimura. Ozawa's carriers, by now depleted of most of their aircraft, were to serve as a decoy for Kurita's and Nishimura's battleships, which were to use the distraction to attack the invasion fleet directly.[36] Kurita's ships were detected in the San Bernardino Strait on 24 October, and in the ensuing Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, American carrier aircraft sank the powerful battleship Musashi, causing Kurita to temporarily reverse course. This convinced Admiral William F. Halsey, the commander of Third Fleet, to send the fast carrier task force to destroy the 1st Mobile Fleet, which had by then been detected. Washington steamed north with the carriers, and on the way Halsey established TF 34, under Lee's command, consisting of Washington and five other fast battleships, seven cruisers, and eighteen destroyers.[37]

On the morning of 25 October, Mitscher began his first attack on the Northern Force, initiating the Battle off Cape Engaño; over the course of six strikes on the Japanese fleet, the Americans sank all four carriers and damaged two old battleships that had been converted into hybrid carriers. Unknown to Halsey and Mitscher, Kurita had resumed his approach through the San Bernardino Strait late on 24 October and passed into Leyte Gulf the next morning. While Mitscher was occupied with the decoy Northern Force, Kurita moved in to attack the invasion fleet; in the Battle off Samar, he was held off by a group of escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts, TU 77.4.3, known as Taffy 3. Frantic calls for help later that morning led Halsey to detach Lee's battleships to head south and intervene.[38]

However, Halsey waited more than an hour after receiving orders from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, to detach TF 34; still steaming north during this interval, the delay added two hours to the battleships' voyage south. A need to refuel destroyers further slowed TF 34's progress south.[39] Heavy resistance from Taffy 3 threw Kurita's battleships and cruisers into disarray and led him to break off the attack before Washington and the rest of TF 34 could arrive.[40] Halsey detached the battleships Iowa and New Jersey as TG 34.5 to pursue Kurita through the San Bernardino Strait while Lee took the rest of his ships further southwest to try to cut off his escape, but both groups arrived too late. The historian H. P. Wilmott speculated that had Halsey detached TF 34 promptly and not delayed the battleships by refueling the destroyers, the ships could have easily arrived in the strait ahead of Center Force and, owing to the marked superiority of their radar-directed main guns, destroyed Kurita's ships.[41]

Later operations

After the battle, the units of TF 38 withdrew to Ulithi to replenish fuel and ammunition for further operations in the Philippines. The carrier task forces got underway again on 2 November for more strikes on the airfields on Luzon and the Visayas that continued until 14 November, when they withdrew again to Ulithi, arriving there three days later. On 18 November, Lee exchanged flagships with Rear Admiral Edward Hanson, the commander of BatDiv 9, who had used South Dakota as his flagship. At the same time, Washington was transferred to TG 38.3, in company with South Dakota and North Carolina. The ships sortied on 22 November for gunnery training while the carriers conducted strikes independently against targets in the Philippines over the next three days. She arrived back in Ulithi on 2 December, where the crew made repairs and loaded ammunition and stores for future operations.[42]

The units of TF 38 got underway again on 11 December for more attacks on Luzon to suppress Japanese aircraft as the amphibious force prepared for its next landing on the island of Mindoro in the western Philippines. The raid lasted from 14 to 16 December, and while the fleet withdrew to refuel on 17 December, Typhoon Cobra swept through the area, battering the fleet and sinking three destroyers. The damage inflicted on the fleet delayed further support of ground troops for two days and the continuing bad weather led Halsey to break off operations; the ships arrived back in Ulithi on 24 December.[42]

On 30 December, the fleet got underway to make preparatory strikes for the landing on Luzon; Washington remained with TG 38.3 for the operation. The carriers struck Formosa again on 3 and 4 January 1945; after refueling at sea on 5 January, the carriers struck kamikazes massed at airfields on Luzon on 6 and 7 January to neutralize them before the invasion of Lingayen Gulf. Further attacks on Formosa and Okinawa followed on 9 January. The next day, the carrier groups entered the South China Sea, where it refueled and then struck targets in French Indochina on the assumption that significant Japanese naval forces were present, but only merchant ships and a number of minor warships were caught and sunk there. During these raids, other elements of the Allied fleet invaded Lingayen Gulf on Luzon.[43]

Iwo Jima and Okinawa campaigns

_with_TG_38_3_off_Okinawa_1945.jpeg.webp)

In February, she escorted carriers during attacks on the Japanese island of Honshu to disrupt Japanese air forces that might interfere with the planned invasion of Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands. Fifth Fleet had re-assumed command of the fast carrier task force by this point, and Washington was now part of TG 58.4. The fleet sortied from Ulithi on 10 February, and after conducting training exercises off Tinian on the 12th, refueled at sea on 14 February and continued on north to launch strikes on the Tokyo area two days later. The raids continued through 17 February and the next day, the fleet withdrew to refuel and TG 58.4 was sent to hit other islands in the Bonin chain to further isolate Iwo Jima. During the preparatory bombardment for that attack, Washington, North Carolina, and the heavy cruiser Indianapolis were detached from the task group to reinforce TF 54, the assault force for the invasion; she remained on station during the marine assault and provided fire support as they fought their way across the island through 22 February. The next day, the carrier groups reassembled and refueled on 24 February for further operations against the Japanese mainland.[7][44]

After leaving Iwo Jima, the fleet resumed air attacks on the Home Islands to prepare for the next amphibious assault on Okinawa in the Ryukus. The first of these, on 25 and 26 February, hit targets in the Tokyo area, followed by another attack on Iwo Jima the next day. The fleet refueled on 28 February and on 1 March raided Okinawa, thereafter returning to Ulithi on 4 March.[45] While in Ulithi, the fleet was reorganized and Washington was transferred to TG 58.3. The fleet sortied on 14 March for additional attacks on Japan; the ships refueled on 16 March on the way and they launched their aircraft two days later to hit targets in Kyushu. The attacks continued into the next day, causing significant damage to Japanese facilities on the island and sinking or damaging numerous warships. The task groups withdrew to refuel and reorganize on 22 March, as several carriers had been damaged by kamikaze and air attacks.[46]

On 24 March, Washington bombarded Japanese positions on Okinawa as the fleet continued to pummel defenses before the invasion. By this time, Washington had been transferred to TG 58.2. Carrier raids on the Home Islands and the Ryukus continued after landing on Okinawa on 1 April. While operating off the island, the fleet came under heavy and repeated kamikaze attacks, one of the largest of which took place on 7 April in concert with the sortie of the battleship Yamato. Washington was not damaged in these attacks, however, which were largely defeated by the carriers' combat air patrols. On 19 April, the battleship again closed with Okinawa to bombard Japanese positions as the Marines fought their way south. Washington remained off the island until late May, when she was detached for an overhaul. She proceeded first to San Pedro Bay, Leyte, arriving there on 1 June, before departing for Puget Sound on 6 June. While crossing the Pacific, she stopped in Guam and Pearl Harbor before finally arriving in Bremerton on 23 June. Her refit continued into September, by which time Japan had surrendered on 15 August and formally ended the war on 2 September.[7][47]

Post-war

_and_USS_Enterprise_(CV-6)_in_the_Panama_Canal%252C_October_1945.jpg.webp)

After completing her refit in September, Washington conducted sea trials, followed by a short period of training while based in San Pedro, Los Angeles. She then got underway for the Panama Canal and on 6 October joined TG 11.6 on the way, thereafter passing through the canal and steaming north to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. She arrived there on 17 October and took part in Navy Day celebrations on 27 October. Slated to take part in Operation Magic Carpet, the sea-lift operation to bring American service members home, Washington went into the shipyard in Philadelphia to be modified to carry additional personnel. Additional space was provided by substantially reducing the crew, to 84 officers and 835 enlisted men; with the war over, the ship's weapons needed no gun crews. The work was completed by 15 November, when she got underway for Britain. She arrived in Southampton on 22 November. Washington embarked a contingent of Army personnel totaling 185 officers and 1,479 enlisted men and then re-crossed the Atlantic to New York, where she was decommissioned on 27 June 1947.[7]

She was assigned to the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, based in New York, where she remained through the 1950s. Beginning already in 1946, the Ships Characteristics Board authorized the removal a number of the 40 mm guns from the North Carolina and South Dakota class battleships that had been decommissioned. These guns were then installed on the Iowa-class battleships when they were reactivated for the Korean War. Washington and the other battleships had their 20 mm batteries removed entirely by October 1951. The Navy considered modernizing Washington and North Carolina in May 1954, which would have provided an anti-aircraft battery of twelve 3 in (76 mm) guns in twin turrets. The ships' slow speed prevented them from effectively serving with the carrier task forces and the Navy determined that a speed of 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) would be necessary. To achieve this, the power plant would have to provide 240,000 shp (180,000 kW) at the current displacement; even removing the aft turret and using that magazine space for additional boilers would not have produced the necessary power. By removing all of the belt armor, the ship would have only required 216,000 shp (161,000 kW) to reach the desired speed, but the aft hull would have had to have been significantly rebuilt to accommodate the larger screws that would have been required. The Navy considered the possibility of removing the ships' current propulsion system altogether and replacing it with the same type as used in the Iowas, which were capable of 35 kn (65 km/h; 40 mph), but there was not enough room to fit the larger system. To reach the same speed, Washington would have needed to have all side armor and all three turrets removed in addition to a power plant capable of 470,000 shp (350,000 kW).[7][48]

The cost of the project, estimated at around $40 million per ship, was deemed to be prohibitively expensive and so the project was abandoned.[49] The ship remained in the inventory until 1 June 1960, when the ship was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. She was sold for scrap on 24 May 1961. Washington was towed to the Lipsett Division of Luria Brothers and broken up thereafter.[7]

Footnotes

Notes

- /45 refers to the length of the gun in terms of calibers. A /45 gun is 45 times long as it is in bore diameter.

- In the context of small arms, caliber refers to the bore diameter; in this case, a .50-caliber machine gun is a half-inch in diameter.

Citations

- Friedman 1985, pp. 244–265.

- Friedman 1980, p. 97.

- Friedman 1985, p. 447.

- Friedman 1985, p. 276.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 276–277.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 274–275.

- DANFS.

- Friedman 1985, p. 275.

- Rohwer, pp. 152, 154.

- Blair, pp. 514–515, 528.

- Rohwer, p. 154.

- Rohwer, p. 162.

- Rohwer, pp. 166–167.

- Rohwer, pp. 175–176.

- Rohwer, pp. 201, 205–206.

- Hornfischer, pp. 245–246, 251, 336–337.

- Frank, pp. 463–470.

- Hornfischer, p. 346.

- Hornfischer, pp. 354–355.

- Frank, pp. 475–477.

- Hornfischer, pp. 201, 358–360.

- Frank, pp. 477–479.

- Frank, pp. 479–481.

- Frank, pp. 481–483.

- Frank, pp. 483–488.

- Rohwer, p. 224.

- Hornfischer, p. 383.

- Frank, p. 548.

- Friedman 1985, p. 347.

- Rohwer, p. 335.

- Y'Blood, pp. 68, 79.

- Rohwer, p. 354.

- Rohwer, p. 364.

- Rohwer, pp. 364, 366.

- Wilmott, p. 47.

- Wilmott, pp. 73–74.

- Wilmott, pp. 110–123.

- Rohwer, p. 367.

- Wilmott, p. 195.

- Rohwer, pp. 367–368.

- Wilmott, pp. 195, 214–215.

- Evans 2015.

- Rohwer, pp. 380, 383.

- Rohwer, pp. 393–394.

- Rohwer, p. 393.

- Rohwer, pp. 399–400.

- Rohwer, pp. 407–408, 410.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 390, 392, 397–398.

- Friedman 1985, p. 397.

References

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-boat War: The Hunters, 1939–1942. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-58839-1.

- Evans, Mark L. (12 November 2015). "South Dakota (BB-57) 1943-44". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. Marmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-016561-6.

- Friedman, Norman (1980). "United States of America". In Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 86–166. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-715-9.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80670-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- "Washington VIII (BB-56)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 24 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Wilmott, H. P. (2015). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01901-1.

- Y'Blood, William T. (2012). Red Sun Setting: The Battle of the Philippine Sea. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-197-9.

Further reading

- Garzke, William H. & Dulin, Robert O. (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-099-0.

- Lundgren, Robert (2008). "Question 39/43: Loss of HIJMS Kirishima". Warship International. XLV (4): 291–296. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Musicant, Ivan (1986). Battleship at War, The Epic Story of the USS Washington. Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-70487-0.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.

External links

![]() Media related to USS Washington (BB-56) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to USS Washington (BB-56) at Wikimedia Commons