Veal

Veal is the meat of calves, in contrast to the beef from older cattle. Veal can be produced from a calf of either sex and any breed, however most veal comes from young male calves of dairy breeds which are not used for breeding.[1][2] Generally, veal is more expensive by weight than beef from older cattle. Veal production is a way to add value to dairy bull calves and to utilize whey solids, a byproduct from the manufacturing of cheese.[3]

Definitions and types

There are several types of veal, and terminology varies by country.

- Bob veal

- Calves slaughtered as early as 2 hours or 2–3 days old (at most 1 month old), yielding carcasses weighing from to 9–27 kilograms (20–60 pounds).[4]

- Formula-fed ("Milk Fed", "Special Fed" or "white") veal

- Calves are raised on a fortified milk formula diet plus solid feed. The majority of veal meat produced in the US are from milk-fed calves. The meat colour is ivory or creamy pink, with a firm, fine, and velvety appearance. In Canada, calves intended for the milk-fed veal stream are usually slaughtered when they reach 20 to 24 weeks of age, weighing 200 to 230 kg (450 to 500 lb).[5]

- Nonformula-fed ("red" or "grain-fed") veal

- Calves raised on grain, hay, or other solid food, in addition to milk. The meat is darker in colour, and some additional marbling and fat may be apparent. In Canada, the grain-fed veal stream is usually marketed as calf, rather than veal. The calves are slaughtered at 22 to 26 weeks of age weighing 290 to 320 kg (650 to 700 lb).[6]

- Young beef (in Europe; "rose veal" in the UK)

- Calves raised on farms in association with the UK Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals' Freedom Food programme.[7] The name comes from the pink colour, which is partly a result of the calves being slaughtered later at about 35 weeks of age.[8]

Similar terms are used in the US, including calf, bob, intermediate, milk-fed, and special-fed.[9][10]

Culinary uses

In Italian, French and other Mediterranean cuisines, veal is often in the form of cutlets, such as the Italian cotoletta or the famous Austrian dish Wiener Schnitzel. Some classic French veal dishes include fried escalopes, fried veal Grenadines (small, thick fillet steaks), stuffed paupiettes, roast joints, and blanquettes. Because veal is lower in fat than many meats, care must be taken in preparation to ensure that it does not become tough. Veal is often coated in preparation for frying or eaten with a sauce. Veal parmigiana is a common Italian-American dish made with breaded veal cutlets.

In addition to providing meat, the bones of calves are used to make a stock that forms the base for sauces and soups such as demi-glace. Calf stomachs are also used to produce rennet, which is used in the production of cheese. Calf offal is also widely regarded as the most prized animal offal.[11]

Production

Male dairy calves are commonly used for veal production as they do not lactate and are therefore surplus to the requirements of the dairy industry. Newborn veal calves are generally separated from the cow within three days.[10][2]

Calves are sometimes raised in individual stalls for the first several weeks as a sort of quarantine,[10] and then moved to groupings of two or more calves.

Milk-fed veal calves consume a diet consisting of milk replacer, formulated with mostly milk-based proteins and added vitamins and minerals supplemented with solid feeds. This type of diet is similar to infant formula and is also one of the most common diets used for calves in the veal industry.[12] Grain-fed calves normally consume a diet of milk replacer for the first six to eight weeks and then move on to a mostly maize-based diet.[13]

A farm veterinarian creates and provides a health program for the herd. Veal calves need proper amounts of water, adequate nutrition, and safe and comfortable environments to thrive.[12]

Animal welfare

Veal production has been a controversial topic. The ethics of veal production have been challenged by animal welfare advocates and some methods are cited as animal cruelty by multiple animal welfare organizations. These organizations and some of their members consider several practices and procedures of veal production to be inhumane. Public efforts by these organizations are placing pressure on the veal industry to change some of its methods.[14][15][16]

Some of these practices are relevant to both group and individual housing systems.

Restricted space

In the past, one aspect of veal production cited as cruelty in the industry was the lack of space veal calves were provided. Space was often deliberately restricted by the producer to stop the animal from exercising, as exercise was thought to make the meat turn redder and tougher.[17] Modern veal production facilities in the US allow sufficient room for the calf to lie down, stand, stretch, and groom themselves.[10]

Abnormal gut development

Some systems of veal production rear calves that are denied access to any solid feed[18] and are fed a liquid milk replacer. They may also be deprived of bedding to prevent them from eating it. This dietary restriction completely distorts the normal development of the rumen and predisposes the calf to infectious enteritis (scouring or diarrhea) and chronic indigestion.[19] Furthermore, calves with an underdeveloped gut are more likely to be found to have hairballs in the rumen at slaughter; the accumulation of hairballs in the rumen can impair digestion.[16]

Abnormal behaviours

Rearing calves in deprived conditions without a teat can lead to the development of abnormal oral behaviour. Some of these may develop into oral stereotypies such as sucking, licking or biting inanimate objects, and by tongue rolling and tongue playing. "Purposeless oral activity" occupies 15% of the time in crated calves but only 2–3% in group-housed calves.[16]

Increased disease susceptibility

Veal calves' dietary intake of iron was restricted[18] to achieve a target haemoglobin concentration of around 4.6 mmol/L; normal concentration of haemoglobin in the blood is greater than 7 mmol/L. Calves with blood haemoglobin concentrations of below 4.5 mmol/L may show signs of increased disease susceptibility and immunosuppression.[16]

Alternative agricultural uses for male dairy calves include raising bob veal (slaughtered at two or three days old),[20] raising calves as "red veal" without the severe dietary restrictions needed to create pale meat (requiring fewer antibiotic treatments and resulting in lower calf mortality),[21] and as dairy beef.[22]

In 2008 to 2009 in the US, the demand for free-raised veal rose rapidly.[23][24]

Veal crates

Veal crates are a close-confinement system of raising veal calves. Many calves raised for veal, including in Canada[25] and the US, were confined in crates which typically measure approximately 66–76 cm (2 ft 2 in – 2 ft 6 in) wide. The calves were housed individually and the crates may prevent physical contact between adjacent calves, and sometimes also visual contact.[19] In the past, crated calves were often tied to the front of the crate with a tether which restricted movement.[15][19][26] Floors are often slatted and sloped. This allows urine and manure to fall under the crate to help maintain a clean environment for the calf. In some veal crate systems, the calves were also kept in the dark without bedding and fed nothing but milk.[27][28] Veal crates were designed to limit movement of the animal because it was believed by producers that the meat turns redder and tougher if the animals were allowed to exercise.[17] The diet is sometimes highly regulated to control sources of iron, which again makes the meat redder.

In the US, the use of tethers in veal crates to prevent movement by veal calves was a principal source of controversy in veal farming. Many veal farmers started improving conditions in their veal farms in the 2000s.[23][29] Veal tethering is criticized because the ability of the calves to move is highly restricted; the crates may have unsuitable flooring; the calves spend their entire lives indoors, experience prolonged sensory, social, and exploratory deprivation; and the calves are more susceptible to high amounts of stress and disease.[14] All milk-fed veal calves in the US are now untethered and are raised in groups by at least ten weeks of age if not earlier.[30]

Cruelty to calves

Calves need to exercise to ensure normal bone and muscle development. Calves at pasture not only walk but also run about, jump and play. Calves in veal crates cannot turn around let alone walk or run. When finally taken out of their crates to go for slaughter, calves may stumble or have difficulty walking. There is a general increase in knee and hock swelling as crate width decreases.[16] These challenges no longer exist with US farmers adopting the practice of raising veal in groups.[1]

Under natural conditions calves continue to suckle 3 to 6 times a day for up to 5 months.[16] Veal crates prevent this social interaction. Furthermore, some calves were reared in crates with solid walls that prevented visual or tactile contact with their neighbours. It has been shown that calves will work for social contact with other calves.[26]

To maintain personal hygiene and help prevent disease, calves lick themselves to groom. Cattle naturally lick all the parts of their body they can reach, however, tethering prevents calves from licking the hind parts of their body. Excessive licking of the forelegs (another abnormal behaviour) is common in stall and tether systems.[26]

In the US, young milk-fed veal calves may be raised in individual pens up to a maximum of ten weeks of age and are typically in visual and tactile contact with their neighbors. Milk-fed veal calves are never tethered, allowing them to easily groom themselves.[30]

Drug use

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulations do not permit the use of hormones on veal calves for any reason. They do, however, permit the use of antibiotics in veal raising to treat or prevent disease.[10][30]

In 2004, the USDA expressed concern that the use of illegal drugs might be widespread in the veal industry.[31] In 2004, a USDA official found a lump on a veal calf in a Wisconsin veal farm, which turned out to be an illegal hormone implant.[31] In 2004, the USDA stated "Penicillin is not used in calf raising: tetracycline has been approved, but is not widely used."[10]

Crate bans

Europe

In 1990, the British government banned transporting calves in close-confinement crates.[27][28] Veal crates were banned across the European Union (EU) in January 2007.[18][32][33]

Veal calf production, as such, is not allowed in many northern European countries, such as in Finland. In Finland, giving feed, drink or other nutrition which is known to be dangerous to an animal which is being cared for is prohibited, as well as failing to give nutrients the lack of which is known to cause the animal to fall ill. The Finnish Animal Welfare Act of 1996[34] and the Finnish Animal Welfare Decree of 1996[35] provided general guidelines for the housing and care of animals, and effectively banned veal crates in Finland. Veal crates are not specifically banned in Switzerland, but most calves are raised outdoors.[36][37]

United States

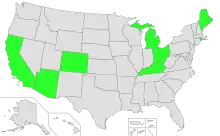

US States with bans on veal crates

States prohibiting veal crates

|

In 2007, the American Veal Association passed a resolution encouraging the entire industry to phase out tethered crate-confinement of calves by 2017, a goal that was met by all milk-fed veal farmers.[38][30]

As of 2015, eight U.S. states ban tethering of calves in veal crates. Nationally, several large veal producers and the American Veal Association are also working to phase out the industry use of tethered veal crates. As of 2017, all American Veal Association members are raising calves in tether free pens and all veal calves are housed in group pens by the time they are 10 weeks of age. State-by-state veal crate bans are as follows:[39]

- Arizona (since 2006, a part of Proposition 204)[40]

- California (effective 2015, a part of Proposition 2)

- Colorado (since 2012)[41]

- Kentucky (Passed in 2014, the Kentucky Livestock Care Standards Commission issued a decision to begin a phase-out period of four years and that by 2018 veal crates will be eliminated from Kentucky farms)[42]

- Maine (since 2011)[43]

- Michigan (effective 2013)[44]

- Ohio (passed 2010, effective 2017)[45]

- Rhode Island (since July 2013)[46]

Current active legislation in:

- New York (proposed in January 2013 and 2014)[47]

- Massachusetts (House[48] and Senate[49] bills filed annually since 2009; current bills would take effect one year after passage)

See also

- List of beef dishes

- List of veal dishes

Further reading

- Costa, J.H.C., von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. and Weary, D.M. (2016). Invited review: Effects of group housing of dairy calves on behavior, cognition, performance, and health. Journal of Dairy Science, 99(4), 2453–2467.

References

- "Veal's Journey from Farm to Food to You". Cattlemen's Beef Board. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Bennett, Jacob M. (2010). The Complete Guide to Grass-Fed Cattle: How to Raise Your Cattle on Natural Grass for Fun and Profit. Atlantic Publishing. p. 197. ISBN 9781601383808.

- "Whey Utilization in Animal Feeding: A Summary and Evaluation 1, 2". Journal of Dairy Science. 59 (3): 556–570. March 1, 1976. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(76)84240-3 – via www.sciencedirect.com.

- "Veal fabrication". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Milk-fed veal definition". Ontario Veal Association. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Grain fed veal definition in Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals". carc-crac.ca. Canadian Agri-Food Research Council. 1998. Archived from the original on August 6, 2007.

- Freedom Food programme

- Hickman, Martin (September 2, 2006). "The ethics of eating: The appeal of veal". Independent News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- "Institutional Meat Product Specifications 300 Fresh Veal and Calf" (PDF). USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. November 7, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "Veal from Farm to Table". USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. August 6, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Montagné, P.: New Concise Larousse Gatronomique, page 1233. Hamlyn, 2007.

- "High Quality Meat Starts at the Farm". Cattlemen's Beef Board. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Management of Grain-Fed Veal Calves". Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (Ontario). September 28, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- "An HSUS Report: The Welfare of Animals in the Veal Industry". hsus.org. Humane Society of the United States. May 8, 2009. Archived from the original on October 30, 2010.

- "Veal crates". The Humane Society of the United States. March 22, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- McKenna, C. (2001). "The case against the veal crate: An examination of the scientific evidence that led to the banning of the veal crate system in the EU and of the alternative group housed systems that are better for calves, farmers and consumers" (PDF). Compassion in World Farming. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Butler, Catherine (December 14, 1995). "Europe plan for ban on veal crates". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Compassion In World Farming. "About calves reared for veal". Compassion In World Farming. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Greter, A. & Levison, L. (2012). "Calf in a box: Individual confinement housing used in veal production" (PDF). British Columbia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- "Facts About Our Food – Veal" (PDF). humanefood.ca. Canadian Coalition for Farm Animals. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011.

- Sargeant JM, Blackwell TE, Martin W, et al. Production indicates, calf health and mortality on seven red veal farms in Ontario. Can J Vet Res 1994;58:196-201.

- Maas J, Robinson PH. Preparing Holstein steer calves for the feedlot. Vet Clin Food Anim 2007;23:269-279

- Black, Jane (October 28, 2009). "The kinder side of veal". Washington Post.

- "Strauss Veal and Marcho Farms Eliminating Confinement by Crate". hsus.org. Humane Society of the United States. February 22, 2007. Archived from the original on August 12, 2009.

- Humane Society International. "Fast facts on veal crates in Canada". Humane Society International. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- "An HSUS Report: The Welfare of Intensively Confined Animals in Battery Cages, Gestation Crates, and Veal Crates" (PDF). The Humane Society of the United States. 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Bentham J. (September 5, 2007). "Veal, without the cruelty". The Guardian. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Atkins, L. (July 28, 2000). "For the love of veal". The Guardian.

- Burros, Marian (April 18, 2007). "Veal to Love, Without the Guilt". The New York Times.

- "Answers to some of the most commonly asked questions about veal farming". vealfarm.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- Weise, Elizabeth (March 28, 2004). "Illegal hormones found in veal calves". USA Today. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "CIWF on Veal Crates (UK ban on bottom of page)". CIWF.org.uk. May 19, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Veal: A Byproduct of the Cruel Dairy Industry". peta.org. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- "Finnish Animal Welfare Act of 1996" (PDF).

- "The Finnish Animal Welfare Decree of 1996" (PDF).

- "Natura Veal". Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "swiss meat – animal protection". Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- "Timeline of Major Farm Animal Protection Advancements". September 8, 2014. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Veal Crates: Unnecessary and Cruel". February 22, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Arizona Makes History for Farm Animals" May 2007

- ""Colorado bans the veal crate and the gestation crate", Compassion in world farming". Ciwf.org.uk. May 19, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Kentucky Bans the Use of Veal Crates on Farms". vegnews.com. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- "Maine Bans Veal Crates". The Exception Magazine. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009.

- "Michigan Adopts Law to Ban Gestation Stalls". Aasv.org. October 14, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Landmark Ohio Animal Welfare Agreement Reached Among HSUS, Ohioans for Humane Farms, Gov. Strickland, and Leading Livestock Organizations". June 30, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Meier, Erica (June 21, 2012). "Victory: Rhode Island Bans Gestation Crates, Veal Crates, and Tail-Docking of Cows". Cok.net. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Assembly Bill A424". nysenate.gov. New York State Senate. January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- Lewis, Jason. "Bill H.1456 An Act to prevent farm animal cruelty". Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- Hedlund, Robert. "Bill S.741 An Act to prevent farm animal cruelty". Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

External links

- Veal.org — From the Cattlemen's Beef Board (USA)