French cuisine

French cuisine (French: Cuisine française) is the cooking traditions and practices from France. It has been influenced over the centuries by the many surrounding cultures of Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium, in addition to the food traditions of the regions and colonies of France.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of France |

|---|

| People |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music and Performing arts |

| Sport |

|

In the 14th century, Guillaume Tirel, a court chef known as "Taillevent", wrote Le Viandier, one of the earliest recipe collections of medieval France. In the 17th century, chefs François Pierre La Varenne and Marie-Antoine Carême spearheaded movements that shifted French cooking away from its foreign influences and developed France's own indigenous style.

Cheese and wine are a major part of the cuisine. They play different roles regionally and nationally, with many variations and appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) (regulated appellation) laws.[1]

Culinary tourism and the Guide Michelin helped to acquaint commoners with the cuisine bourgeoise of the urban elites and the peasant cuisine of the French countryside starting in the 20th century. Many dishes that were once regional have proliferated in variations across the country.

Knowledge of French cooking has contributed significantly to Western cuisines. Its criteria are used widely in Western cookery school boards and culinary education. In November 2010, French gastronomy was added by the UNESCO to its lists of the world's "intangible cultural heritage".[2][3]

History

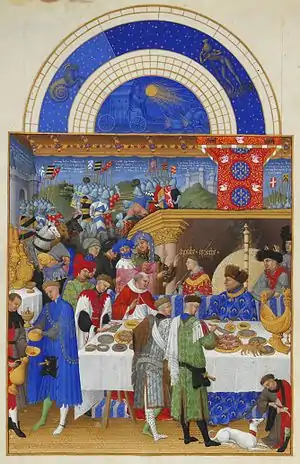

Middle Ages

In French medieval cuisine, banquets were common among the aristocracy. Multiple courses would be prepared, but served in a style called service en confusion, or all at once. Food was generally eaten by hand, meats being sliced off in large pieces held between the thumb and two fingers. The sauces were highly seasoned and thick, and heavily flavored mustards were used.

Pies were a common banquet item, with the crust serving primarily as a container, rather than as food itself, and it was not until the very end of the Late Middle Ages that the shortcrust pie was developed.

Meals often ended with an issue de table, which later changed into the modern dessert, and typically consisted of dragées (in the Middle Ages, meaning spiced lumps of hardened sugar or honey), aged cheese and spiced wine, such as hypocras.[4]: 1–7

The ingredients of the time varied greatly according to the seasons and the church calendar, and many items were preserved with salt, spices, honey, and other preservatives. Late spring, summer, and autumn afforded abundance, while winter meals were more sparse. Livestock were slaughtered at the beginning of winter. Beef was often salted, while pork was salted and smoked. Bacon and sausages would be smoked in the chimney, while the tongue and hams were brined and dried. Cucumbers were brined as well, while greens would be packed in jars with salt. Fruits, nuts and root vegetables would be boiled in honey for preservation. Whale, dolphin and porpoise were considered fish, so during Lent, the salted meats of these sea mammals were eaten.[4]: 9–12

Artificial freshwater ponds (often called stews) held carp, pike, tench, bream, eel, and other fish. Poultry was kept in special yards, with pigeon and squab being reserved for the elite. Game was highly prized, but very rare, and included venison, boar, hare, rabbit, and fowl.

Kitchen gardens provided herbs, including some, such as tansy, rue, pennyroyal, and hyssop, which are rarely used today. Spices were treasured and very expensive at that time—they included pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and mace. Some spices used then, but no longer today in French cuisine are cubebs, long pepper (both from vines similar to black pepper), grains of paradise, and galengale.

Sweet-sour flavors were commonly added to dishes with vinegars and verjus combined with sugar (for the affluent) or honey. A common form of food preparation was to thoroughly cook, pound, and strain mixtures into fine pastes and mushes, something believed to be beneficial to make use of nutrients.[4]: 13–15

Visual display was prized. Brilliant colors were obtained by the addition of, for example, juices from spinach and the green part of leeks. Yellow came from saffron or egg yolk, while red came from sunflower, and purple came from Crozophora tinctoria or Heliotropium europaeum.

Gold and silver leaf were placed on food surfaces and brushed with egg whites. Elaborate and showy dishes were the result, such as tourte parmerienne which was a pastry dish made to look like a castle with chicken-drumstick turrets coated with gold leaf. One of the grandest showpieces of the time was roast swan or peacock sewn back into its skin with feathers intact, the feet and beak being gilded. Since both birds are stringy, and taste unpleasant, the skin and feathers could be kept and filled with the cooked, minced and seasoned flesh of tastier birds, like goose or chicken.[4]: 15–16

The most well known French chef of the Middle Ages was Guillaume Tirel, also known as Taillevent. Taillevent worked in numerous royal kitchens during the 14th century. His first position was as a kitchen boy in 1326. He was chef to Philip VI, then the Dauphin who was son of John II. The Dauphin became King Charles V of France in 1364, with Taillevent as his chief cook. His career spanned sixty-six years, and upon his death he was buried in grand style between his two wives. His tombstone represents him in armor, holding a shield with three cooking pots, marmites, on it.[4]: 18–21

Ancien Régime

Paris was the central hub of culture and economic activity, and as such, the most highly skilled culinary craftsmen were to be found there. Markets in Paris such as Les Halles, la Mégisserie, those found along Rue Mouffetard, and similar smaller versions in other cities were very important to the distribution of food. Those that gave French produce its characteristic identity were regulated by the guild system, which developed in the Middle Ages. In Paris, the guilds were regulated by city government as well as by the French crown. A guild restricted those in a given branch of the culinary industry to operate only within that field.[4]: 71–72

There were two groups of guilds—first, those that supplied the raw materials: butchers, fishmongers, grain merchants, and gardeners. The second group were those that supplied prepared foods: bakers, pastry cooks, sauce makers, poulterers, and caterers. There were also guilds that offered both raw materials and prepared food, such as the charcutiers and rôtisseurs (purveyors of roasted meat dishes). They would supply cooked meat pies and dishes as well as raw meat and poultry. This caused issues with butchers and poulterers, who sold the same raw materials.[4]: 72–73

The guilds served as a training ground for those within the industry. The degrees of assistant cook, full-fledged cook and master chef were conferred. Those who reached the level of master chef were of considerable rank in their individual industry, and enjoyed a high level of income as well as economic and job security. At times, those in the royal kitchens did fall under the guild hierarchy, but it was necessary to find them a parallel appointment based on their skills after leaving the service of the royal kitchens. This was not uncommon as the Paris cooks' guild regulations allowed for this movement.[4]: 73

During the 16th and 17th centuries, French cuisine assimilated many new food items from the New World. Although they were slow to be adopted, records of banquets show Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589?) serving sixty-six turkeys at one dinner.[4]: 81 The dish called cassoulet has its roots in the New World discovery of haricot beans, which are central to the dish's creation, but had not existed outside of the Americas until the arrival of Europeans.[4]: 85

Haute cuisine (pronounced [ot kɥizin], "high cuisine") has foundations during the 17th century with a chef named La Varenne. As author of works such as Le Cuisinier françois, he is credited with publishing the first true French cookbook. His book includes the earliest known reference to roux using pork fat. The book contained two sections, one for meat days, and one for fasting. His recipes marked a change from the style of cookery known in the Middle Ages, to new techniques aimed at creating somewhat lighter dishes, and more modest presentations of pies as individual pastries and turnovers. La Varenne also published a book on pastry in 1667 entitled Le Parfait confitvrier (republished as Le Confiturier françois) which similarly updated and codified the emerging haute cuisine standards for desserts and pastries.[4]: 114–120

Chef François Massialot wrote Le Cuisinier roïal et bourgeois in 1691, during the reign of Louis XIV. The book contains menus served to the royal courts in 1690. Massialot worked mostly as a freelance cook, and was not employed by any particular household. Massialot and many other royal cooks received special privileges by association with the French royalty. They were not subject to the regulation of the guilds; therefore, they could cater weddings and banquets without restriction. His book is the first to list recipes alphabetically, perhaps a forerunner of the first culinary dictionary. It is in this book that a marinade is first seen in print, with one type for poultry and feathered game, while a second is for fish and shellfish. No quantities are listed in the recipes, which suggests that Massialot was writing for trained cooks.[4]: 149–154

The successive updates of Le Cuisinier roïal et bourgeois include important refinements such as adding a glass of wine to fish stock. Definitions were also added to the 1703 edition. The 1712 edition, retitled Le Nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois, was increased to two volumes, and was written in a more elaborate style with extensive explanations of technique. Additional smaller preparations are included in this edition as well, leading to lighter preparations, and adding a third course to the meal. Ragout, a stew still central to French cookery, makes its first appearance as a single dish in this edition as well; prior to that, it was listed as a garnish.[4]: 155

Late 18th century – early 19th century

_by_Jean-Marc_Nattier.png.webp)

Shortly before the French Revolution, dishes like bouchées à la Reine gained prominence. Essentially royal cuisine produced by the royal household, this is a chicken-based recipe served on vol-au-vent created under the influence of Queen Marie Leszczyńska, the Polish-born wife of Louis XV. This recipe is still popular today, as are other recipes from Queen Marie Leszczyńska like consommé à la Reine and filet d'aloyau braisé à la royale. Queen Marie is also credited with introducing Polonaise garnishing to the French diet.

The French Revolution was integral to the expansion of French cuisine, because it abolished the guild system. This meant anyone could now produce and sell any culinary item they wished.

Bread was a significant food source among peasants and the working class in the late 18th century, with many of the nation's "people" being dependent on it. In French provinces, bread was often consumed three times a day by the "people" of France.[5] According to Brace, bread was referred to as the basic dietary item for the masses, and it was also used as a foundation for soup. In fact, bread was so important that harvest, interruption of commerce by wars, heavy flour exploration, and prices and supply were all watched and controlled by the French Government. Among the underprivileged, constant fear of famine was always prevalent. From 1725 to 1789, there were fourteen years of bad yields to blame for low grain supply. In Bordeaux, during 1708–1789, thirty-three bad harvests occurred.[5]

Marie-Antoine Carême was born in 1784, five years before the Revolution. He spent his younger years working at a pâtisserie until he was discovered by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord; he would later cook for Napoleon Bonaparte. Prior to his employment with Talleyrand, Carême had become known for his pièces montées, which were extravagant constructions of pastry and sugar architecture.[6]: 144–145

More important to Carême's career was his contribution to the refinement of French cuisine. The basis for his style of cooking was his sauces, which he named mother sauces. Often referred to as fonds, meaning "foundations", these base sauces, espagnole, velouté, and béchamel, are still known today. Each of these sauces was made in large quantities in his kitchen, then formed the basis of multiple derivatives. Carême had over one hundred sauces in his repertoire.

In his writings, soufflés appear for the first time. Although many of his preparations today seem extravagant, he simplified and codified an even more complex cuisine that existed beforehand. Central to his codification of the cuisine were Le Maître d'hôtel français (1822), Le Cuisinier parisien (1828) and L'Art de la cuisine française au dix-neuvième siècle (1833–5).[6]: 144–148

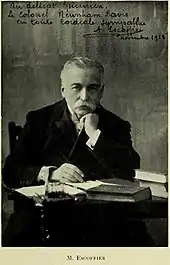

Late 19th century – early 20th century

Georges Auguste Escoffier is commonly acknowledged as the central figure to the modernization of haute cuisine and organizing what would become the national cuisine of France. His influence began with the rise of some of the great hotels in Europe and America during the 1880s-1890s. The Savoy Hotel managed by César Ritz was an early hotel in which Escoffier worked, but much of his influence came during his management of the kitchens in the Carlton from 1898 until 1921. He created a system of "parties" called the brigade system, which separated the professional kitchen into five separate stations.

These five stations included the garde manger that prepared cold dishes; the entremettier prepared starches and vegetables, the rôtisseur prepared roasts, grilled and fried dishes; the saucier prepared sauces and soups; and the pâtissier prepared all pastry and desserts items.

This system meant that instead of one person preparing a dish on one's own, now multiple cooks would prepare the different components for the dish. An example used is oeufs au plat Meyerbeer, the prior system would take up to fifteen minutes to prepare the dish, while in the new system, the eggs would be prepared by the entremettier, kidney grilled by the rôtisseur, truffle sauce made by the saucier and thus the dish could be prepared in a shorter time and served quickly in the popular restaurants.[6]: 157–159

Escoffier also simplified and organized the modern menu and structure of the meal. He published a series of articles in professional journals which outlined the sequence, and he finally published his Livre des menus in 1912. This type of service embraced the service à la russe (serving meals in separate courses on individual plates), which Félix Urbain Dubois had made popular in the 1860s. Escoffier's largest contribution was the publication of Le Guide Culinaire in 1903, which established the fundamentals of French cookery. The book was a collaboration with Philéas Gilbert, E. Fetu, A. Suzanne, B. Reboul, Ch. Dietrich, A. Caillat and others. The significance of this is to illustrate the universal acceptance by multiple high-profile chefs to this new style of cooking.[6]: 159–160

Le Guide Culinaire deemphasized the use of heavy sauces and leaned toward lighter fumets, which are the essence of flavor taken from fish, meat and vegetables. This style of cooking looked to create garnishes and sauces whose function is to add to the flavor of the dish, rather than mask flavors like the heavy sauces and ornate garnishes of the past. Escoffier took inspiration for his work from personal recipes in addition to recipes from Carême, Dubois and ideas from Taillevent's Le Viandier, which had a modern version published in 1897. A second source for recipes came from existing peasant dishes that were translated into the refined techniques of haute cuisine.

Expensive ingredients would replace the common ingredients, making the dishes much less humble. The third source of recipes was Escoffier himself, who invented many new dishes, such as pêche Melba.[6]: 160–162 Escoffier updated Le Guide Culinaire four times during his lifetime, noting in the foreword to the book's first edition that even with its 5,000 recipes, the book should not be considered an "exhaustive" text, and that even if it were at the point when he wrote the book, "it would no longer be so tomorrow, because progress marches on each day."[7]

This period is also marked by the appearance of the nouvelle cuisine. The term "nouvelle cuisine" has been used many times in the history of French cuisine which emphasized the freshness, lightness and clarity of flavor and inspired by new movements in world cuisine. In the 1740s, Menon first used the term, but the cooking of Vincent La Chapelle and François Marin was also considered modern. In the 1960s, Henri Gault and Christian Millau revived it to describe the cooking of Paul Bocuse, Jean and Pierre Troisgros, Michel Guérard, Roger Vergé and Raymond Oliver.[8] These chefs were working toward rebelling against the "orthodoxy" of Escoffier's cuisine. Some of the chefs were students of Fernand Point at the Pyramide in Vienne, and had left to open their own restaurants. Gault and Millau "discovered the formula" contained in ten characteristics of this new style of cooking.[6]: 163–164

The characteristics that happened during this period were: 1. A rejection of excessive complication in cooking. 2. The cooking times for most fish, seafood, game birds, veal, green vegetables and pâtés was greatly reduced in an attempt to preserve the natural flavors. Steaming was an important trend from this characteristic. 3. The cuisine was made with the freshest possible ingredients. Fourth, large menus were abandoned in favor of shorter menus. 5. Strong marinades for meat and game ceased to be used.[6]: 163–164

6. They stopped using heavy sauces such as espagnole and béchamel thickened with flour based "roux" in favor of seasoning their dishes with fresh herbs, quality butter, lemon juice, and vinegar. 7. They used regional dishes for inspiration instead of haute cuisine dishes. 8. New techniques were embraced and modern equipment was often used; Bocuse even used microwave ovens. 9. The chefs paid close attention to the dietary needs of their guests through their dishes. 10. And finally, the chefs were extremely inventive and created new combinations and pairings.[6]: 163–164

Some have speculated that a contributor to nouvelle cuisine was World War II when animal protein was in short supply during the German occupation.[9] By the mid-1980s food writers stated that the style of cuisine had reached exhaustion and many chefs began returning to the haute cuisine style of cooking, although much of the lighter presentations and new techniques remained.[6]: 163–164

When the French colonized Vietnam, one of the most famous and popular dishes, Pot-au-feu was subsequently introduced to the local "people". While it didn't directly create the widely recognizable Vietnamese dish, Pho, it served as a reference for the modern-day form of Pho.

National cuisine

There are many dishes that are considered part of French national cuisine today.

A meal often consists of three courses, hors d'œuvre or entrée (introductory course, sometimes soup), plat principal (main course), fromage (cheese course) or dessert, sometimes with a salad offered before the cheese or dessert.

- Hors d'œuvre

Basil salmon terrine

Basil salmon terrine Bisque is a smooth and creamy French potage.

Bisque is a smooth and creamy French potage. Foie gras with mustard seeds and green onions in duck jus

Foie gras with mustard seeds and green onions in duck jus

- Plat principal

Pot-au-feu is a cuisine classique dish.

Pot-au-feu is a cuisine classique dish..jpg.webp) Steak frites is a simple and popular dish.

Steak frites is a simple and popular dish. Blanquette de veau

Blanquette de veau

- Pâtisserie

Typical French pâtisserie

Typical French pâtisserie Mille-feuille

Mille-feuille

Éclair

Éclair

- Dessert

Mousse au chocolat

Mousse au chocolat

Île flottante

Île flottante

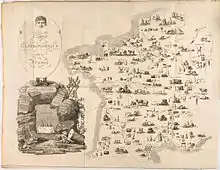

Regional cuisine

.svg.png.webp)

French regional cuisine is characterized by its extreme diversity and style. Traditionally, each region of France has its own distinctive cuisine.[10]

Paris and Île-de-France

Paris and Île-de-France are central regions where almost anything from the country is available, as all train lines meet in the city. Over 9,000 restaurants exist in Paris and almost any cuisine can be obtained here. High-quality Michelin Guide-rated restaurants proliferate here.[11]

Champagne, Lorraine, and Alsace

Game and ham are popular in Champagne, as well as the special sparkling wine simply known as Champagne. Fine fruit preserves are known from Lorraine as well as the quiche Lorraine.[12] As region of historically Allemanic German culture Alsace has retained Elements of German cuisine, especially similar to those from the neighboring Palatinate and Baden region, but has implemented French influences since France first took control of the region in the 17th century. As such, beers made in the area are similar to the style of bordering Germany. Dishes like choucroute (French for sauerkraut) are also popular.[11]: 55 Many "Eaux de vie" (distilled alcohol from fruit) also called schnaps are from this region, due to a wide variety of local fruits (cherry, raspberry, pear, grapes) and especially prunes (mirabelle, plum).[9]:259,295

Flute of Champagne wine

Flute of Champagne wine Alsatian Flammekueche

Alsatian Flammekueche Quiche

Quiche Choucroute garnie

Choucroute garnie Andouillette

Andouillette

Nord Pas-de-Calais, Picardy, Normandy, and Brittany

The coastline supplies many crustaceans, sea bass, monkfish and herring. Normandy has top-quality seafood, such as scallops and sole, while Brittany has a supply of lobster, crayfish and mussels.

Normandy is home to a large population of apple trees; apples are often used in dishes, as well as cider and Calvados. The northern areas of this region, especially Nord, grow ample amounts of wheat, sugar beets and chicory. Thick stews are found often in these northern areas as well.

The produce of these northern regions is also considered some of the best in the country, including cauliflower and artichokes. Buckwheat grows widely in Brittany as well and is used in the region's galettes, called jalet, which is where this dish originated.[11]: 93

Crème Chantilly, created at the Château de Chantilly.

Crème Chantilly, created at the Château de Chantilly. Camembert, cheese specialty from Normandy

Camembert, cheese specialty from Normandy

Belon oysters

Belon oysters

Loire Valley and central France

High-quality fruits come from the Loire Valley and central France, including cherries grown for the liqueur Guignolet and Belle Angevine pears. The strawberries and melons are also of high quality.

Fish are seen in the cuisine, often served with a beurre blanc sauce, as well as wild game, lamb, calves, Charolais cattle, Géline fowl, and goat cheeses.

Young vegetables are used often, as are the specialty mushrooms of the region, champignons de Paris. Vinegars from Orléans are a specialty ingredient used as well.[11]: 129, 132

Burgundy and Franche-Comté

Burgundy and Franche-Comté are known for their wines. Pike, perch, river crabs, snails, game, redcurrants, blackcurrants are from both Burgundy and Franche-Comté.

Amongst savorous specialties accounted in the Cuisine franc-comtoise from the Franche-Comté region are Croûte aux morilles, Poulet à la Comtoise, trout, smoked meats and cheeses such as Mont d'Or, Comté and Morbier which are best eaten hot or cold, the exquisite Coq au vin jaune and the special dessert gâteau de ménage.

Charolais beef, poultry from Bresse, sea snail, honey cake, Chaource and Epoisses cheese are specialties of the local cuisine of Burgundy. Dijon mustard is also a specialty of Burgundy cuisine. Crème de cassis is a popular liquor made from the blackcurrants. Oils are used in the cooking here, types include nut oils and rapeseed oil.[11]: 153, 156, 166, 185

Bœuf bourguignon

Bœuf bourguignon Coq au vin

Coq au vin Escargots, with special tongs and fork

Escargots, with special tongs and fork Beaujolais wine

Beaujolais wine Dijon mustard

Dijon mustard Comté cheese and Vin jaune

Comté cheese and Vin jaune Gâteau de ménage

Gâteau de ménage

Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

The area covers the old province of Dauphiné, once known as the "larder" of France, that gave its name to gratin dauphinois,[13] traditionally made in a large baking dish rubbed with garlic. Successive layers of potatoes, salt, pepper and milk are piled up to the top of the dish. It is then baked in the oven at low temperature for 2 hours.[14]

Fruit and young vegetables are popular in the cuisine from the Rhône valley, as are wines like Hermitage AOC, Crozes-Hermitage AOC and Condrieu AOC. Walnuts and walnut products and oil from Noix de Grenoble AOC, lowland cheeses, like St. Marcellin, St. Félicien and Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage.

Poultry from Bresse, guinea fowl from Drôme and fish from the Dombes, a light yeast-based cake, called Pogne de Romans and the regional speciality, Raviole du Dauphiné, and there is the short-crust "Suisse", a Valence biscuit speciality.

Lakes and mountain streams in Rhône-Alpes are key to the cuisine as well. Lyon and Savoy supply sausages while the Alpine regions supply their specialty cheeses like Beaufort, Abondance, Reblochon, Tomme and Vacherin.[15][16][17][18]

Mères lyonnaises are female cooks particular to this region who provide local gourmet establishments.[19] Celebrated chefs from this region include Fernand Point, Paul Bocuse, the Troisgros brothers and Alain Chapel.[20]

The Chartreuse Mountains are the source of the green and yellow Digestif liquor, Chartreuse produced by the monks of the Grande Chartreuse.[11]: 197, 230

Since the 2014 administrative reform, the ancient area of Auvergne is now part of the region. One of its leading chefs is Regis Marcon.

Gratin dauphinois

Gratin dauphinois Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage

Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage Chartreuse Elixir Végétal

Chartreuse Elixir Végétal Salade de ravioles

Salade de ravioles Condrieu wine

Condrieu wine Suisse de Valence biscuit

Suisse de Valence biscuit Bleu de Bresse

Bleu de Bresse Poulet de Bresse chicken salad

Poulet de Bresse chicken salad Rosette de Lyon charcuterie

Rosette de Lyon charcuterie Noix de Grenoble, unusual trilaterally symmetric walnut

Noix de Grenoble, unusual trilaterally symmetric walnut.jpg.webp) Beaufort cheeses ripening in a cellar

Beaufort cheeses ripening in a cellar

Poitou-Charentes and Limousin

Oysters come from the Oléron-Marennes basin, while mussels come from the Bay of Aiguillon.

High-quality produce comes from the region's hinterland, especially goat cheese. This region and in the Vendée is grazing ground for Parthenaise cattle, while poultry is raised in Challans.

The region of Poitou-Charentes purportedly produces the best butter and cream in France. Cognac is also made in the region along the river Charente.

Limousin is home to the Limousin cattle, as well as sheep. The woodlands offer game and mushrooms. The southern area around Brive draws its cooking influence from Périgord and Auvergne to produce a robust cuisine.[11]: 237

Bordeaux, Périgord, Gascony, and Basque country

Bordeaux is known for its wine, with certain areas offering specialty grapes for wine-making. Fishing is popular in the region for the cuisine, sea fishing in the Bay of Biscay, trapping in the Garonne and stream fishing in the Pyrenees.

The Pyrenees also has lamb, such as the Agneau de Pauillac, as well as sheep cheeses. Beef cattle in the region include the Blonde d'Aquitaine, Boeuf de Chalosse, Boeuf Gras de Bazas, and Garonnaise.

Free-range chicken, turkey, pigeon, capon, goose and duck prevail in the region as well. Gascony and Périgord cuisines includes pâtés, terrines, confits and magrets. This is one of the regions notable for its production of foie gras, or fattened goose or duck liver.

The cuisine of the region is often heavy and farm based. Armagnac is also from this region, as are prunes from Agen.[11]: 259, 295

Toulouse, Quercy, and Aveyron

Gers, a department of France, is within this region and has poultry, while La Montagne Noire and Lacaune area offer hams and dry sausages.

White corn is planted heavily in the area both for use in fattening ducks and geese for foie gras and for the production of millas, a cornmeal porridge. Haricot beans are also grown in this area, which are central to the dish cassoulet.

The finest sausage in France is saucisse de Toulouse, which also part of cassoulet of Toulouse. The Cahors area produces a specialty "black wine" as well as truffles and mushrooms.

This region also produces milk-fed lamb. Unpasteurized ewe's milk is used to produce Roquefort in Aveyron, while in Laguiole is producing unpasteurized cow's milk cheese. Salers cattle produce milk for cheese, as well as beef and veal products.

The volcanic soils create flinty cheeses and superb lentils. Mineral waters are produced in high volume in this region as well.[11]: 313 Cabécou cheese is from Rocamadour, a medieval settlement erected directly on a cliff, in the rich countryside of Causses du Quercy.

This area is one of the region's oldest milk producers; it has chalky soil, marked by history and human activity, and is favourable for the raising of goats.

Cassoulet

Cassoulet Aligot

Aligot Roquefort cheese

Roquefort cheese

Roussillon, Languedoc, and Cévennes

Restaurants are popular in the area known as Le Midi. Oysters come from the Étang de Thau, to be served in the restaurants of Bouzigues, Mèze, and Sète. Mussels are commonly seen here in addition to fish specialties of Sète, bourride, tielles and rouille de seiche.

In the Languedoc jambon cru, sometimes known as jambon de montagne is produced. High quality Roquefort comes from the brebis (sheep) on the Larzac plateau.

The Les Cévennes area offers mushrooms, chestnuts, berries, honey, lamb, game, sausages, pâtés and goat cheeses. Catalan influence can be seen in the cuisine here with dishes like brandade made from a purée of dried cod wrapped in mangold leaves. Snails are plentiful and are prepared in a specific Catalan style known as a cargolade. Wild boar can be found in the more mountainous regions of the Midi.[11]: 349, 360

Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur

The Provence and Côte d'Azur region is rich in quality citrus, vegetables, fruits and herbs; the region is one of the largest suppliers of all these ingredients in France. The region also produces the largest amount of olives, and creates superb olive oil. Lavender is used in many dishes found in Haute Provence. Other important herbs in the cuisine include thyme, sage, rosemary, basil, savory, fennel, marjoram, tarragon, oregano, and bay leaf.[21] Honey is a prized ingredient in the region.

Seafood is widely available throughout the coastal area and is heavily represented in the cuisine. Goat cheeses, air-dried sausages, lamb, beef, and chicken are popular here. Garlic and anchovies are used in many of the region's sauces, as in Poulet Provençal, which uses white wine, tomatoes, herbs, and sometimes anchovies, and Pastis is found everywhere that alcohol is served.

The cuisine uses a large amount of vegetables for lighter preparations. Truffles are commonly seen in Provence during the winter. Thirteen desserts in Provence are the traditional Christmas dessert,[22] e.g. quince cheese, biscuits, almonds, nougat, apple, and fougasse.

Rice is grown in the Camargue, which is the northernmost rice growing area in Europe, with Camargue red rice being a specialty.[11]: 387, 403, 404, 410, 416 Anibal Camous, a Marseillais who lived to be 104, maintained that it was by eating garlic daily that he kept his "youth" and brilliance. When his eighty-year-old son died, the father mourned: "I always told him he wouldn't live long, poor boy. He ate too little garlic!"

Ratatouille

Ratatouille.jpg.webp)

Bouillabaisse

Bouillabaisse Daube

Daube Pissaladière

Pissaladière Pan bagnat

Pan bagnat Vacqueyras wine

Vacqueyras wine

Salade Mesclun

Salade Mesclun Pieds paquets

Pieds paquets

Corsica

Goats and sheep proliferate on the island of Corsica, and lamb are used to prepare dishes such as stufato, ragouts and roasts. Cheeses are also produced, with brocciu being the most popular.

Chestnuts, growing in the Castagniccia forest, are used to produce flour, which is used in turn to make bread, cakes and polenta. The forest provides acorns used to feed the pigs and boars that provide much of the protein for the island's cuisine. Fresh fish and seafood are common.

The island's pork is used to make fine hams, sausage and other unique items including coppa (dried rib cut), lonzu (dried pork fillet), figatellu (smoked and dried liverwurst), salumu (a dried sausage), salcietta, Panzetta, bacon, and prisuttu (farmer's ham).

Clementines (which hold an AOC designation), lemons, nectarines and figs are grown there. Candied citron is used in nougats, while and the aforementioned brocciu and chestnuts are also used in desserts.

Corsica offers a variety of wines and fruit liqueurs, including Cap Corse, Patrimonio, Cédratine, Bonapartine, liqueur de myrte, vins de fruit, Rappu, and eau-de-vie de châtaigne.[11]: 435, 441, 442

French Guiana

French Guianan cuisine or Guianan cuisine is a blend of the different cultures that have settled in French Guiana. Creole and Chinese restaurants are common in major cities such as Cayenne, Kourou and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni. Many indigenous animal species such as caiman and tapir are used in spiced stews.

Specialties by season

French cuisine varies according to the season. In summer, salads and fruit dishes are popular because they are refreshing and produce is inexpensive and abundant. Greengrocers prefer to sell their fruits and vegetables at lower prices if needed, rather than see them rot in the heat. At the end of summer, mushrooms become plentiful and appear in stews throughout France. The hunting season begins in September and runs through February. Game of all kinds is eaten, often in elaborate dishes that celebrate the success of the hunt. Shellfish are at their peak when winter turns to spring, and oysters appear in restaurants in large quantities.

With the advent of deep-freeze and the air-conditioned hypermarché, these seasonal variations are less marked than hitherto, but they are still observed, in some cases due to legal restrictions. Crayfish, for example, have a short season and it is illegal to catch them out of season.[23] Moreover, they do not freeze well.

Foods and ingredients

French regional cuisines use locally grown vegetables, such as pomme de terre (potato), blé (wheat), haricots verts (a type of French green bean), carotte (carrot), poireau (leek), navet (turnip), aubergine (eggplant), courgette (zucchini), and échalotte (shallot).

French regional cuisines use locally grown fungi, such as truffe (truffle), champignon de Paris (button mushroom), chanterelle ou girolle (chanterelle), pleurote (en huître) (oyster mushrooms), and cèpes (porcini).

Common fruits include oranges, tomatoes, tangerines, peaches, apricots, apples, pears, plums, cherries, strawberries, raspberries, redcurrants, blackberries, grapes, grapefruit, and blackcurrants.

Varieties of meat consumed include poulet (chicken), pigeon (squab), canard (duck), oie (goose, the source of foie gras), bœuf (beef), veau (veal), porc (pork), agneau (lamb), mouton (mutton), caille (quail), cheval (horse), grenouille (frog), and escargot (snails). Commonly consumed fish and seafood include cod, canned sardines, fresh sardines, canned tuna, fresh tuna, salmon, trout, mussels, herring, oysters, shrimp and calamari.

Eggs often eaten as: omelettes, hard-boiled with mayonnaise, scrambled plain, scrambled haute cuisine preparation, œuf à la coque.

Herbs and seasonings vary by region, and include fleur de sel, herbes de Provence, tarragon, rosemary, marjoram, lavender, thyme, fennel, and sage.

Fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as fish and meat, can be purchased either from supermarkets or specialty shops. Street markets are held on certain days in most localities; some towns have a more permanent covered market enclosing food shops, especially meat and fish retailers. These have better shelter than the periodic street markets.

Charolais cattle

Charolais cattle

Haricots verts

Haricots verts Piments d'Espelette

Piments d'Espelette Fleur de sel de Guérande

Fleur de sel de Guérande

Poulet de Bresse

Poulet de Bresse Blé (Wheat)

Blé (Wheat) Black Périgord truffle

Black Périgord truffle

Structure of meals

Breakfast

Le petit déjeuner (breakfast) is traditionally a quick meal consisting of tartines (slices) of French bread with butter and honey or jam (sometimes brioche), along with café au lait (also called café crème), or black coffee, or tea[24] and rarely hot chicory. Children often drink hot chocolate in bowls or cups along with their breakfasts. Croissants, pain aux raisins or pain au chocolat (also named chocolatine in the south-west of France) are mostly included as a weekend treat. Breakfast of some kind is always served in cafés opening early in the day.

There are also savoury dishes for breakfast. An example is le petit déjeuner gaulois or petit déjeuner fermier with the famous long narrow bread slices topped with soft white cheese or boiled ham, called mouillettes,[25] which is dipped in a soft-boiled egg and some fruit juice and hot drink.

Another variation called le petit déjeuner chasseur, meant to be very hearty, is served with pâté and other charcuterie products. A more classy version is called le petit déjeuner du voyageur, where delicatessens serve gizzard, bacon, salmon, omelet, or croque monsieur, with or without soft-boiled egg and always with the traditional coffee/tea/chocolate along fruits or fruit juice. When the egg is cooked sunny-side over the croque-monsieur, it is called a croque-madame.

In Germinal and other novels, Émile Zola also reported the briquet: two long bread slices stuffed with butter, cheese and or ham. It can be eaten as a standing/walking breakfast, or meant as a "second" one before lunch.

In the movie Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis, Philippe Abrams (Kad Merad) and Antoine Bailleul (Dany Boon) share together countless breakfasts consisting of tartines de Maroilles (a rather strong cheese) along with their hot chicory.

Lunch

Le déjeuner (lunch) is a two-hour mid-day meal or a one-hour lunch break . In some smaller towns and in the south of France, the two-hour lunch may still be customary . Sunday lunches are often longer and are taken with the family.[26] Restaurants normally open for lunch at noon and close at 2:30 pm. Some restaurants are closed on Monday during lunch hours.[27]

In large cities, a majority of working "people" and students eat their lunch at a corporate or school cafeteria, which normally serves complete meals as described above; it is not usual for students to bring their own lunch to eat. For companies that do not operate a cafeteria, it is mandatory for employees to be given lunch vouchers as part of their employee benefits. These can be used in most restaurants, supermarkets and traiteurs; however, workers having lunch in this way typically do not eat all three courses of a traditional lunch due to price and time constraints. In smaller cities and towns, some working "people" leave their workplaces to return home for lunch. Also, an alternative, especially among blue-collar workers, is eating sandwiches followed by a dessert; both dishes can be found ready-made at bakeries and supermarkets at budget prices.

Dinner

Le dîner (dinner) often consists of three courses, hors d'œuvre or entrée (appetizers or introductory course, sometimes soup), plat principal (main course), and a cheese course or dessert, sometimes with a salad offered before the cheese or dessert. Yogurt may replace the cheese course, while a simple dessert would be fresh fruit. The meal is often accompanied by bread, wine and mineral water. Most of the time the bread would be a baguette which is very common in France and is made almost every day. Main meat courses are often served with vegetables, along with potatoes, rice or pasta.[26]: 82 Restaurants often open at 7:30 pm for dinner, and stop taking orders between the hours of 10:00 pm and 11:00 pm. Some restaurants close for dinner on Sundays.[27]: 342

Beverages and drinks

In French cuisine, beverages that precede a meal are called apéritifs (literally: "that opens the appetite"), and can be served with amuse-bouches (literally: "mouth amuser"). Those that end it are called digestifs.

- Apéritifs

The apéritif varies from region to region: Pastis is popular in the south of France, Crémant d'Alsace in the eastern region. Champagne can also be served. Kir, also called Blanc-cassis, is a common and popular apéritif-cocktail made with a measure of crème de cassis (blackcurrant liqueur) topped up with white wine. The phrase Kir Royal is used when white wine is replaced with a Champagne wine. A simple glass of red wine, such as Beaujolais nouveau, can also be presented as an apéritif, accompanied by amuse-bouches. Some apéritifs can be fortified wines with added herbs, such as cinchona, gentian and vermouth. Trade names that sell well include Suze (the classic gentiane), Byrrh, Dubonnet, and Noilly Prat.

- Digestifs

Digestifs are traditionally stronger, and include Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados, Eau de vie and fruit alcohols.

Christmas

A typical French Christmas dish is turkey with chestnuts. Other common dishes are smoked salmon, oysters, caviar and foie gras. The Yule log (bûche de Noël) is a very French tradition during Christmas. Chocolate and cakes also occupy a prominent place for Christmas in France. This cuisine is normally accompanied by Champagne. Tradition says that thirteen desserts complete the Christmas meal in reference to the twelve apostles and Christ.[28][29][30][31]

Food establishments

History

The modern restaurant has its origins in French culture. Prior to the late 18th century, diners who wished to "dine out" would visit their local guild member's kitchen and have their meal prepared for them. However, guild members were limited to producing whatever their guild registry delegated to them.[32]: 8–10 These guild members offered food in their own homes to steady clientele that appeared day-to-day but at set times. The guest would be offered the meal table d'hôte, which is a meal offered at a set price with very little choice of dishes, sometimes none at all.[32]: 30–31

The first steps toward the modern restaurant were locations that offered restorative bouillons, or restaurants—these words being the origin of the name "restaurant". This step took place during the 1760s–1770s. These locations were open at all times of the day, featuring ornate tableware and reasonable prices. These locations were meant more as meal replacements for those who had "lost their appetites and suffered from jaded palates and weak chests."[32]: 34–35

In 1782 Antoine Beauvilliers, pastry chef to the future Louis XVIII, opened one of the most popular restaurants of the time—the Grande Taverne de Londres—in the arcades of the Palais-Royal. Other restaurants were opened by chefs of the time who were leaving the failing monarchy of France, in the period leading up to the French Revolution. It was these restaurants that expanded upon the limited menus of decades prior, and led to the full restaurants that were completely legalized with the advent of the French Revolution and abolition of the guilds. This and the substantial discretionary income of the French Directory's nouveau riche helped keep these new restaurants in business.[32]: 140–144

.jpg.webp)

| English | French | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Restaurant | More than 5,000 in Paris alone, with varying levels of prices and menus. Open at certain times of the day, and normally closed one day of the week. Patrons select items from a printed menu. Some offer regional menus, while others offer a modern styled menu. Waiters and waitresses are trained and knowledgeable professionals. By law, a prix-fixe menu must be offered, although high-class restaurants may try to conceal the fact. Few French restaurants cater to vegetarians. The Guide Michelin rates many of the better restaurants in this category.[11]: 30 | |

| Bistro(t) | Often smaller than a restaurant and many times using chalk board or verbal menus. Wait staff may well be untrained. Many feature a regional cuisine. Notable dishes include coq au vin, pot-au-feu, confit de canard, calves' liver and entrecôte.[11]: 30 | |

| Bistrot à Vin | Similar to cabarets or tavernes of the past in France. Some offer inexpensive alcoholic drinks, while others take pride in offering a full range of vintage AOC wines. The foods in some are simple, including sausages, ham and cheese, while others offer dishes similar to what can be found in a bistro.[11]: 30 | |

| Bouchon | Found in Lyon, they produce traditional Lyonnaise cuisine, such as sausages, duck pâté or roast pork. The dishes can be quite fatty, and heavily oriented around meat. There are about twenty officially certified traditional bouchons, but a larger number of establishments describing themselves using the term.[33] | |

| Brewery | Brasserie | These establishments were created in the 1870s by refugees from Alsace-Lorraine. These establishments serve beer, but most serve wines from Alsace such as Riesling, Sylvaner, and Gewürztraminer. The most popular dishes are choucroute and seafood dishes.[11]: 30 In general, a brasserie is open all day every day, offering the same menu.[34] |

| Café | Primarily locations for coffee and alcoholic drinks. Additional tables and chairs are usually set outside, and prices are usually higher for service at these tables. The limited foods sometimes offered include croque-monsieur, salads, moules-frites (mussels and pommes frites) when in season. Cafés often open early in the morning and shut down around nine at night.[11]: 30 | |

| Salon de Thé | These locations are more similar to cafés in the rest of the world. These tearooms often offer a selection of cakes and do not offer alcoholic drinks. Many offer simple snacks, salads, and sandwiches. Teas, hot chocolate, and chocolat à l'ancienne (a popular chocolate drink) are offered as well. These locations often open just prior to noon for lunch and then close late afternoon.[11]: 30 | |

| Bar | Based on the American style, many were built at the beginning of the 20th century (particularly around World War I, when young American expatriates were quite common in France, particularly Paris). These locations serve cocktails, whiskey, pastis and other alcoholic drinks.[11]: 30 | |

| Estaminet | Typical of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, these small bars/restaurants used to be a central place for farmers, mine or textile workers to meet and socialize, sometimes the bars would be in a grocery store.[35] Customers could order basic regional dishes, play boules, or use the bar as a meeting place for clubs.[36] These estaminets almost disappeared, but are now considered a part of Nord-Pas-de-Calais history, and therefore preserved and promoted. | |

Restaurant staff

Larger restaurants and hotels in France employ extensive staff and are commonly referred to as either the kitchen brigade for the kitchen staff or dining room brigade system for the dining room staff. This system was created by Georges Auguste Escoffier. This structured team system delegates responsibilities to different individuals who specialize in certain tasks. The following is a list of positions held both in the kitchen and dining rooms brigades in France:[11]: 32

| Section | French | English | Duty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kitchen brigade | Chef de cuisine | Head chef | Responsible for overall management of kitchen. They supervise staff, and create menus and new recipes with the assistance of the restaurant manager, make purchases of raw food items, train apprentices and maintain a sanitary and hygienic environment for the preparation of food.[11]: 32 |

| Sous-chef de cuisine | Deputy Head chef | Receives orders directly from the chef de cuisine for the management of the kitchen and often represents the chef de cuisine when he or she is not present.[11]: 32 | |

| Chef de partie | Senior chef | Responsible for managing a given station in the kitchen where they specialize in preparing particular dishes. Those that work in a lesser station are referred to as a demi-chef.[11]: 32 | |

| Cuisinier | Cook | This position is an independent one where they usually prepare specific dishes in a station. They may be referred to as a cuisinier de partie.[11]: 32 | |

| Commis | Junior cook | Also works in a specific station, but reports directly to the chef de partie and takes care of the tools for the station.[11]: 32 | |

| Apprenti(e) | Apprentice | Many times they are students gaining theoretical and practical training in school and work experience in the kitchen. They perform preparatory or cleaning work.[11]: 30 | |

| Plongeur | Dishwasher | Cleans dishes and utensils and may be entrusted with basic preparatory jobs.[11]: 32 | |

| Marmiton | Pot and pan washer | In larger restaurants, takes care of all the pots and pans instead of the plongeur.[11]: 33 | |

| Saucier | Saucemaker/sauté cook | Prepares sauces, warm hors d'œuvres, completes meat dishes and in smaller restaurants may work on fish dishes and prepare sautéed items. This is one of the most respected positions in the kitchen brigade.[11]: 32 | |

| Rôtisseur | Roast cook | Manages a team of cooks that roasts, broils and deep fries dishes.[11]: 32 | |

| Grillardin | Grill cook | In larger kitchens this person prepares the grilled foods instead of the rôtisseur.[37]: 8 | |

| Friturier | Fry cook | In larger kitchens this person prepares fried foods instead of the rôtisseur.[37] | |

| Poissonnier | Fish cook | Prepares fish and seafood dishes.[11]: 33 | |

| Entremetier | Entrée preparer | Prepares soups and other dishes not involving meat or fish, including vegetable dishes and egg dishes.[11]: 32 | |

| Potager | Soup cook | In larger kitchens, this person reports to the entremetier and prepares the soups.[37] | |

| Legumier | Vegetable cook | In larger kitchen this person also reports to the entremetier and prepares the vegetable dishes.[37] | |

| Garde manger | Pantry supervisor | Responsible for preparation of cold hors d'œuvres, prepares salads, organizes large buffet displays and prepares charcuterie items.[11]: 30 | |

| Tournant | Spare hand/ roundsperson | Moves throughout kitchen assisting other positions in kitchen. | |

| Pâtissier | Pastry cook | Prepares desserts and other meal end sweets, and in locations without a boulanger also prepares breads and other baked items. They may also prepare pasta for the restaurant.[11]: 33 | |

| Confiseur | Prepares candies and petit fours in larger restaurants instead of the pâtissier.[37] | ||

| Glacier | Prepares frozen and cold desserts in larger restaurants instead of the pâtissier.[37] | ||

| Décorateur | Prepares show pieces and specialty cakes in larger restaurants instead of the pâtissier.[37]: 8–9 | ||

| Boulanger | Baker | Prepares bread, cakes and breakfast pastries in larger restaurants instead of the pâtissier.[11]: 33 | |

| Boucher | Butcher | Butchers meats, poultry and sometimes fish. May also be in charge of breading meat and fish items.[37] | |

| Aboyeur | Announcer/ expediter | Takes orders from dining room and distributes them to the various stations. This position may also be performed by the sous-chef de partie.[37] | |

| Communard | Prepares the meal served to the restaurant staff.[37] | ||

| Garçon de cuisine | Performs preparatory and auxiliary work for support in larger restaurants.[11]: 33 | ||

| Dining room brigade | Directeur de la restauration | General manager | Oversees economic and administrative duties for all food-related business in large hotels or similar facilities including multiple restaurants, bars, catering and other events.[11]: 33 |

| Directeur de restaurant | Restaurant manager | Responsible for the operation of the restaurant dining room, which includes managing, training, hiring and firing staff, and economic duties of such matters. In larger establishments there may be an assistant to this position who would replace this person in their absence.[11]: 33 | |

| Maître d'hôtel | Welcomes guests, and seats them at tables. They also supervise the service staff. Commonly deals with complaints and verifies patrons' bills.[11]: 33 | ||

| Chef de salle | Commonly in charge of service for the full dining room in larger establishments; this position can be combined into the maître d'hotel position.[37] | ||

| Chef de rang | The dining room is separated into sections called rangs. Each rang is supervised by this person to coordinate service with the kitchen.[11]: 33 | ||

| Demi-chef de rang | Back server | Clears plates between courses if there is no commis débarrasseur, fills water glasses and assists the chef de rang.[37] | |

| commis de rang | |||

| Commis débarrasseur | Clears plates between courses and the table at the end of the meal.[11]: 33 | ||

| Commis de suite | In larger establishments, this person brings the different courses from the kitchen to the table.[11]: 33 | ||

| Chef d'étage | Captain | Explains the menu to the guest and answers any questions. This person often performs the tableside food preparations. This position may be combined with the chef de rang in smaller establishments.[37] | |

| Chef de vin | Wine server | Manages wine cellar by purchasing and organizing as well as preparing the wine list. Also advises the guests on wine choices and serves the wine.[11]: 33 | |

| Sommelier | |||

| chef sommelier | In larger establishments, this person will manage a team of sommeliers.[11]: 33 | ||

| chef caviste | |||

| Serveur de restaurant | Server | This position found in smaller establishments performs the multiple duties of various positions in the larger restaurants in the service of food and drink to the guests.[11]: 33 | |

| Responsable de bar | Bar manager | Manages the bar in a restaurant, which includes ordering and creating drink menus; they also oversee the hiring, training and firing of barmen. Also manages multiple bars in a hotel or other similar establishment.[11]: 33 | |

| Chef de bar | |||

| Barman | Bartender | Serves alcoholic drinks to guests.[11]: 33 | |

| Dame du vestiaire | Coat room attendant who receives and returns guests' coats and hats.[11]: 33 | ||

| Voituriers | Valet | Parks guests' cars and retrieves them when the guests leave.[11]: 33 | |

See also

- Cuisine of Quebec

- Acadian cuisine

- Cajun cuisine

- French Americans

- French Canadians

- French paradox

- Larousse Gastronomique

- Le Répertoire de la Cuisine

- List of French cheeses

- List of French desserts

- List of French dishes

- List of French restaurants

- List of French soups and stews

- List of restaurants in Paris

References

- Miller, Norman (October 2014). "The ABCs of AOC: France's Most Prized Produce". FrenchEntree. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Bon appétit: Your meal is certified by the UN Archived 20 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News

- UNESCO (16 November 2010). "Celebrations, healing techniques, crafts and culinary arts added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage". UNESCO. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Wheaton, Barbara Ketcham (1996). Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789. New York: First Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-684-81857-3.

- Brace, Richard Munthe (1946). "The Problem of Bread and the French Revolution at Bordeaux". The American Historical Review. 51 (4): 649–667. doi:10.2307/1843902. JSTOR 1843902.

- Mennell, Stephen (1996). All Manners of Food: eating and taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the present, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06490-6.

- Escoffier, Georges Auguste (2002). Escoffier: The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. Foreword. ISBN 978-0-471-29016-2.

- Joyeuse encyclopédie anecdotique de la gastronomie, Michel Ferracci-Porri and Maryline Paoli, Preface by Christian Millau, Ed. Normant 2012, France ISBN 978-2-915685-55-8

- Hewitt, Nicholas (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Modern French Culture. Cambridge: The Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-521-79465-7.

- "French Country Cooking." Archived 18 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine French-country-decor-guide.com Archived 3 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 2011.

- Dominé, André (2004). Culinaria France. Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbh. ISBN 978-3-8331-1129-7.

- "25 Authentic French Foods Everyone Must Try!". Travel Food Atlas. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Fonvieille, René. (1983). La cuisine dauphinoise a travers les siècles. in 3 volumes. Grenoble: Terre et Mer, see contents: http://www.bibliotheque-dauphinoise.com/cuisine_dauphinoise_fonvieille.html retrieved 12-23-2017

- Arces, d', Amicie. & Vallentin du Cheylard, A. (1997). Cuisine du Dauphiné: Drôme . Hautes Alpes . Isère - de A à Z. Paris: éditions Bonneton. ISBN 2-86253-216-9. See Introduction, pp. 4–8. (in French) https://books.google.fr/books?id=YXOiD7R3pssC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Cuisine+du+Dauphiné:+Drôme,+Hautes-Alpes,+Isère+:+de+A+à+Z&hl=fr&ei=ntk0Te3UIsrY4gaj2pnOCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q&f=false retrieved 12-23-2017

- "Lyon Sausage - : Whats on the menu?". menus.nypl.org. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- "Véritable Saucisson de Lyon". Spécialités Lyonnaises (in French). Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- "The culinary heritage of the French mountains". uk.france.fr. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- "10 fromages de montagne incontournables". www.hardloop.fr (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- Maier, Thomas, A. (2012). Hospitality Leadership Lessons in French Gastronomy: The Story of Guy and Franck Savoy. Authorhouse. ISBN 9781468541083.p.19. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MTts8MF4CRwC&pg=PA19&lpg=PA19&dq=Lyon+gastronomy&source=bl&ots=XXkyv-EdAm&sig=boHw6EN2Ap6mSB_hEK0h8dRdXJw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwivk87336DYAhXiLMAKHUcEA-g4HhDoAQgyMAI#v=onepage&q=Lyon%20gastronomy&f=false retrieved 12-23-2017.

- Buford, Bill. (2011). "Why Lyon is the Food Capital of the World". The Guardian, 13 February 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2011/feb/13/bill-buford-lyon-food-capital retrieved 12-23-2017

- "Nice Cooking". La Cuisine Niçoise. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "Christmas traditions". Provenceweb.fr. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Imported crayfish are unrestricted, and many arrive from Pakistan.

- Larousse Gastronomique. New York: Clarkson Potter. 2009. p. 780. ISBN 978-0-307-46491-0.

- Larousse, Éditions. "Définitions : mouillette - Dictionnaire de français Larousse". www.larousse.fr. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Steele, Ross (2001). The French Way, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Fodor's (2006). See It. France. 2nd ed. New York: Fodor's Travel Publications.

- "10 traditions de Noël françaises - Cheznoscousins.com". 30 December 2014. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Noel dans le monde". Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "LES FETES DE NOEL EN FRANCE". referat.clopotel.ro. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Spang, Rebecca L. (2001). The Invention of the Restaurant, 2nd Ed. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00685-0.

- Boudou, Evelyne; Jean-Marc Boudou (2003). Les bonnes recettes des bouchons lyonnais. Seyssinet: Libris. ISBN 978-2-84799-002-7.

- Ribaut, Jean-Claude (8 February 2007). Le Monde. "Les brasseries ont toujours l'avantage d'offrir un service continu tout au long de la journée, d'accueillir les clients après le spectacle et d'être ouvertes sept jours sur sept, quand les restaurants ferment deux jours et demi par semaine."

"Brasseries have the advantage of offering uninterrupted service all day, seven days a week, and of being open for the after-theatre crowd, whereas restaurants are closed two and a half days of the week." - "Les Estaminets - Taverns". www.leershistorique.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Wytteman, JP, ed. (1988). Le Nord de la préhistoire à nos jours (in French). Bordessoules. p. 260.

- The Culinary Institute of America (2006). The Professional Chef (8th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7645-5734-7.

Further reading

- Patrick Rambourg, Histoire de la cuisine et de la gastronomie françaises, Paris, Ed. Perrin (coll. tempus n° 359), 2010, 381 pages. ISBN 978-2-262-03318-7

- Bryan Newman, "Behind the French Menu",

External links

- France stages first-ever Gastronomy Day Radio France Internationale in English