Diet in Hinduism

Diet in Hinduism varies with its diverse traditions. While Hindu scripture doesn't make a particular ruling between non-vegetarianism and vegetarianism, some of the scriptures deem a vegetarian diet to be ideal based on the concept of ahimsa, non-violence and compassion towards all beings. According to Pew Research Center survey 44% of Hindus say they are vegetarian.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

History

According to archeological finds, Indus Valley civilisation had dominance of meat diet of animals such as cattle, buffalo, goat, pig and chicken.[2][3] This continued towards much of Vedic Period. In post Vedic Period, due to influence of Jainism and Buddhism, most Brahmin abandoned animal sacrifice and many adopted Vegetarianism.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] According to estimate around 33% of all Hindus are vegetarians.[11]

According to anthropologist Louis Dumont, Jainism and Buddhism challenged and threatened Brahminical hegemony by introducing new principles such as ahimsa, vegetarianism, and renunciation. The Brahmins adopted the new ideas in an effort to survive when their position was threatened. For instance, Brahmins consumed liquor and meat including beef, before the Jain-Buddhist heretics emerged. But following the Jain-Buddhist challenge, Brahmins adopted a vegetarian and alcohol-free diet.[12]

Diet in Hindu scriptures and texts

The Vedas

Evidence from the Vedas suggests the diet of the Vedic people consisted of cereals, initially barley but later dominated by rice, pulses such as māsha (urad), mudga (moong), and masūra (masoor), vegetables such as lotus roots, lotus stem, bottle gourd and milk products, mainly of cows, but also of buffaloes and goats.[13] The Vedas describe animals including bulls, horses, rams and goats being sacrificed and eaten.[14] Although cows held an elevated position in the Vedas,[15] barren cows were also sacrificed. Even then, the word aghnyā ('not to be eaten', 'inviolable') is used for cows multiple times, with some Rigvedic composers considering the whole bovine species, both cows and bulls, inviolable.[14]

Steven J. Rosen suggests that meat might only have been eaten as part of ritual sacrifices and not otherwise.[16] Acts of animal sacrifice were not fully accepted as there were signs of unease and tension owing to the 'gory brutality of sacrificial butchery' dating back to as early as the older Vedas.[17] The earliest reference to the idea of ahimsa or non-violence to animals (pashu-ahimsa) in any literature, apparently in a moral sense, is found in the Kapisthala Katha Samhita of the Yajurveda (KapS 31.11), written about the 8th century BCE.[18] The Shatapatha Brahmana contains one of the earliest statements against meat eating, and the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, has an injunction against killing 'all living entities'. Injunctions against meat-eating also appear in the Dharmasutras.[19]

Dharmaśāstras

According to Kane, one who is about to eat food should greet the food when it is served to him, should honour it, never speak ill, and never find fault in it.[20][21]

The Dharmasastra literature, states Patrick Olivelle, admonishes "people not to cook for themselves alone", offer it to the gods, to forefathers, to fellow human beings as hospitality and as alms to the monks and needy.[20] Olivelle claims all living beings are interdependent in matters of food and thus food must be respected, worshipped and taken with care.[20] Olivelle states that the Shastras recommend that when a person sees food, he should fold his hands, bow to it, and say a prayer of thanks.[20]

The reverence for food reaches a state of extreme in the renouncer or monk traditions in Hinduism.[20] The Hindu tradition views procurement and preparation of food as necessarily a violent process, where other life forms and nature are disturbed, in part destroyed, changed and reformulated into something edible and palatable. The mendicants (sannyasin, ascetics) avoid being the initiator of this process, and therefore depend entirely on begging for food that is left over of householders.[20] In pursuit of their spiritual beliefs, states Olivelle, the "mendicants eat other people's left overs".[20] If they cannot find left overs, they seek fallen fruit or seeds left in field after harvest.[20]

The forest hermits of Hinduism, on the other hand, do not even beg for left overs.[20] Their food is wild and uncultivated. Their diet would consist mainly of fruits, roots, leaves, and anything that grows naturally in the forest.[20] They avoided stepping on plowed land, lest they hurt a seedling. They attempted to live a life that minimizes, preferably eliminates, the possibility of harm to any life form.[20]

Manusmriti

The Manusmriti discusses diet in chapter 5, where like other Hindu texts, it includes verses that strongly discourage meat eating, as well as verses where meat eating is declared appropriate in times of adversity and various circumstances, recommending that the meat in such circumstances be produced with minimal harm and suffering to the animal.[22] The verses 5.48-5.52 of Manusmriti explain the reason for avoiding meat as follows (abridged),

One can never obtain meat without causing injury to living beings... he should, therefore, abstain from meat. Reflecting on how meat is obtained and on how embodied creatures are tied up and killed, he should quit eating any kind of meat... The man who authorizes, the man who butchers, the man who slaughters, the man who buys or sells, the man who cooks, the man who serves, and the man who eats – these are all killers. There is no greater sinner than a man who, outside of an offering to gods or ancestors, wants to make his own flesh thrive at the expense of someone else's.

— Manusmriti, 5.48-5.52, translated by Patrick Olivelle[22]

In contrast, verse 5.33 of Manusmriti states that a man may eat meat in a time of adversity, verse 5.27 recommends that eating meat is okay if not eating meat may place a person's health and life at risk, while various verses such as 5.31 and 5.39 recommend that the meat be produced as a sacrifice.[22] In verses 3.267 to 3.272, Manusmriti approves of fish and meats of deer, antelope, poultry, goat, sheep, rabbit and others as part of sacrificial food. However, Manusmriti is a law book not a spritiual book. So it permits to eat meat but it doesn't promote.[23] In an exegetical analysis of Manusmriti, Patrick Olivelle states that the document shows opposing views on eating meat was common among ancient Hindus, and that underlying emerging thought on appropriate diet was driven by ethic of non-injury and spiritual thoughts about all life forms, the trend being to reduce the consumption of meat and favour a non-injurious vegetarian lifestyle.[24]

Ramayan

According to Achaya, ancient aryans ate meat of all kinds. He describes a meal in Ramayana that included roasted buffalo calves, venison, meat curries, and sauces made from tamarind, and pomegranate. [25]

Mahabharata

Mahabharata contains numerous stories glorifying non-violence towards animals and has some of the strongest statements against slaughter of animals—three chapters of the Epic are dedicated to the evils of meat-eating. Bhisma declares compassion to be the highest religious principle, and compares eating of animal flesh to eating the flesh of one's son. Nominally acknowledging Manu's authorisation of meat-eating in sacrificial context, Bhisma explains to Yudhiṣṭhira that "one who abstains from doing so acquires the same merit as that accrued from the performance of even a horse sacrifice" and that "those desirous of heaven perform sacrifice with seeds instead of animals". It is stated in Mahabharata that animal sacrifices were introduced only when people began to resort to violence in the treta yuga, a less pure and compassionate age, and were not present in the sat yuga, 'the golden age'.[26]

Tirukkuṛaḷ

Another ancient Indian text, the Tirukkuṛaḷ, originally written in the South Indian language of Tamil, states moderate diet as a virtuous lifestyle and criticizes "non-vegetarianism" in its Pulaan Maruthal (abstinence from flesh or meat) chapter, through verses 251 through 260.[27][28][29] Verse 251, for instance, questions "how can one be possessed of kindness, who, to increase his own flesh, eats the flesh of other creatures." It also says that "the wise, who are devoid of mental delusions, do not eat the severed body of other creatures" (verse 258), suggesting that "flesh is nothing but the despicable wound of a mangled body" (verse 257). It continues to say that not eating meat is a practice more sacred than the most sacred religious practices ever known (verse 259) and that only those who refrain from killing and eating the kill are worthy of veneration (verse 260). This text, written before 400 CE, and sometimes called the Tamil Veda, discusses eating habits and its role in a healthy life (Mitahara), dedicating Chapter 95 of Book II to it.[30] The Tirukkuṛaḷ states in verses 943 through 945, "eat in moderation, when you feel hungry, foods that are agreeable to your body, refraining from foods that your body finds disagreeable". Valluvar also emphasizes overeating has ill effects on health, in verse 946, as "the pleasures of health abide in the man who eats moderately. The pains of disease dwell with him who eats excessively."[30][31][32][33]

Puranas

The Puranic texts fiercely oppose violence against animals in many places "despite following the pattern of being constrained by the Vedic imperative to nominally accept it in sacrificial contexts". The most important Puranic text, the Bhagavata Purana goes farthest in repudiating animal sacrifice—refraining from harming all living beings is considered the highest dharma. The text states that the sin of harming animals cannot be washed away by performing "sham sacrifices", just as "mud cannot be washed away by mud". It graphically presents the horrific karmic reactions accrued from the performance of animal sacrifices—those who mercilessly cook animals and birds go to kumbhipaka and are fried in boiling oil and those who perform sham sacrifices are themselves cut to pieces in viśasana hell. The Skanda Purana states that the sages were dismayed by animal sacrifice and considered it against dharma, claiming that sacrifice is supposed to be performed with grains and milk. It narrates that animal sacrifice was only permitted to feed the population during a famine, yet the sages did not slaughter animals even as they died of starvation. The Matsya Purana contains a dialogue between sages who disapprove of violence against animals, preferring rites involving oblations of fruits and vegetables. The text states that the negative karma accrued from violence against animals far outweighs any benefits.[34]

Diet and Caste

Vegetarian castes are regarded to be superior than non-vegetarian caste. Eaters of clean animals like goats and sheep are considered higher compared to those who consume unclean animals like pigs and domesticated fowl. Carcasses eaters are lower to those who consume the meat of animals that have been killed for food. In addition to being an indication of poor social, economic, and ritual status, eating carcasses is considered to be eating impure meat because death makes the animal impure.[35]

Sanskritisation

The process of Sanskritisation, a term coined by M. N. Srinivas in the 1950s, leads lower castes to adopt practices of ritually higher castes in order to improve the status of their community. One of these practices include adoption of a vegetarian diet.Example of this practice includes the Patidar, and other Gujarati Hindu communities who have adopted Vaishnavism, and vegetarianism that goes with it.[36][37]This was also seen in the north indian Chamar caste.[38]

Contemporary Hindu diet

According to an estimate 33% of Hindus are vegetarian.[11] According to a 2021 Pew Research Center survey, 44% of Hindus say they are vegetarian.[39]

Lacto-vegetarian diet

Hinduism does not require a vegetarian diet,[40] but some Hindus avoid eating meat because it minimizes hurting other life forms.[41] Vegetarianism is considered satvic, that is purifying the body and mind lifestyle in some Hindu texts.[42][43]

Lacto-vegetarianism is favored by many Hindus, which includes milk-based foods and all other non-animal derived foods, but it excludes meat and eggs.[44] There are three main reasons for this: the principle of nonviolence (ahimsa) applied to animals,[45] the intention to offer only vegetarian food to their preferred deity and then to receive it back as prasad, and the conviction that non-vegetarian food is detrimental for the mind and for spiritual development.[42][46] Many Hindus point to scriptural bases, such as the Mahabharata's maxim that "Nonviolence is the highest duty and the highest teaching",[47] as advocating a vegetarian diet.

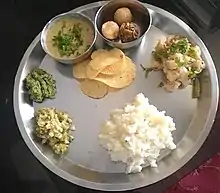

A typical modern urban Hindu lacto-vegetarian meal is based on a combination of grains such as rice and wheat, legumes, green vegetables, and dairy products.[48] Depending on the geographical region the staples may include millet based flatbreads. Fat derived from slaughtered animals is avoided.[49]

A number of Hindus, particularly those following the Vaishnav tradition, refrain from eating onions and garlic either totally or during Chaturmas period (roughly July - November of the Gregorian calendar).[50] In Maharashtra, a number of Hindu families also do not eat any egg plant (Brinjal / Aubergine) preparations during this period.[51] The followers of ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness, Hare Krishna) abstain from meat, fish, and fowl. The related Pushtimargi sect followers also avoid certain vegetables such as onion, mushrooms and garlic, out of the belief that these are tamas (harmful).[49][52] The mainly Gujarati Swaminarayan movement members staunchly adhere to a diet that is devoid of meat, eggs,seafood, onioins and garlic.[53]

Non-vegetarian diet

Hinduism does not prohibit a non-vegetarian diet.[54] Although majority of Indian Hindus are non vegetarians and consume eggs, fish, chicken and meat, a large numbers of Hindus are vegetarian.[55] According to an estimate on diaspora Hindus, only about 10% of Hindus in Suriname are vegetarians and less than five percent of Hindus in Guyana are vegetarians.[56]

Non-vegetarian Indians mostly prefer poultry, fish, other seafood, goat, and sheep as their sources of meat.[57] In Eastern and coastal south-western regions of India, fish and seafood is the staple of most of the local communities. For economic reasons, even meat-eating Hindus in India can only afford to have lacto-vegetarian meals on most days.[58][59] Globally, India consumes the least amount of meat per capita.[60]

Hindus who eat meat, often distinguish all other meat from beef. The respect for cow is part of Hindu belief, and most Hindus avoid meat sourced from cow[49] as cows are treated as a motherly giving animal,[49] considered as another member of the family.[61] A small minority of Nepalese Hindu sects sacrifice buffalo at the Gadhimai festival, but consider cows different from buffalo or other red meat sources. However, the sacrifice of buffalo was banned by the Gadhimai Temple Trust in 2015.[62][63]

The Cham Hindus of Vietnam also do not eat beef.[64][65]

Some Hindus who eat non-vegetarian food abstain from eating non-vegetarian food during festivals such as Janmastami.[66]In Bengal, on the other hand, traditionally goats are ritually sacrificed during the festival of Kali Puja in the Hindu month of Kartik (late October - early November in the Gregorian calendar) and the meat cooked is offered to the deity, and then consumed by the devotees as the prasad.[67]

Prasad and Naivedya

Prasad or Prasadam is a religious offering in Hinduism. Most often it is vegetarian food especially cooked for devotees after praise and thanksgiving to a deity. Mahaprasada (also called Bhandarā) ,[68] is the consecrated food offered to the deity in a Hindu temple which is then distributed and partaken by all the devotees regardless of any orientation.[69][70][71] Prasad is closely linked to the term Naivedya (Sanskrit: नैवेद्य), also spelt Naivedhya', naibedya or Naived(h)yam. The food offered to God is called Naivedya, while the sacred food sanctified and returned by God as a blessing is called Prasad. Naivedya and prasad can be non-vegetarian food prepared from an animal such as goat sacrificed for deity such as Kali in Eastern India, or Chhastisgarh. [72]

Diet on Hindu festivals and religious observations

Hindu calendar has many festivals and religious observations, and dishes specific to that festival are prepared.[73][74]

Festival dishes

Hindus prepare special dishes for different festivals. Kheer, and Halwa are two desserts for Diwali. Puran poli, and Gujia are prepared for Holi in different parts of India.[75][76]

Diet on fasting days

Hindu people fast on days such as Ekadashi, in honour of Lord Vishnu or his Avatars, Chaturthi in honour of Ganesh, Mondays in honour of Shiva, or Saturdays in honour of Maruti or Saturn.[77] Only certain kinds of foods are allowed to be eaten during the fasting period. These include milk and other dairy products such as dahi, fruit and starchy Western food items such as sago,[78] potatoes,[79] purple-red sweet potatoes, amaranth seeds,[80] nuts and shama millet.[81] Popular fasting dishes include Farari chevdo, Sabudana Khichadi or peanut soup.[82]

See also

- Buddhist cuisine

- Buddhist vegetarianism

- Christian dietary laws

- Diet in Sikhism

- Etiquette of Indian dining

- Indian vegetarian cuisine

- Islamic dietary laws

- Kashrut (Jewish Dietary Laws)

- List of diets

- Vegetarian cuisine

- Vegetarian Diet Pyramid

- Vegetarianism and religion

Note

References

- Sen 2014, p. 1168.

- "Indus Valley civilization diet had dominance of meat, finds study". India Today. 11 December 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Indus Valley civilisation had meat-heavy diets, preference for beef, reveals study". Scroll. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Dundas 2002, p. 160.

- Dundas 2002, p. 234.

- Dundas 2002, p. 241.

- Wiley 2006, p. 448.

- Granoff 1992, pp. 1–43.

- Tähtinen 1976, pp. 8–9.

- Bombay Samachar, Mumbai:10 Dec, 1904

- Schmidt, Arno; Fieldhouse, Paul (2007). The world religions cookbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-313-33504-4.

- : Dumont touches briefly, very briefly, on the problem, and according to him, the heretical sects of Jainism and Buddhism challenged Brahminical supremacy, and posed a threat to it when they brought in new ideas like ahimsa (non-killing), vegetarianism and renunciation (ibid.: 146-151). Faced with a threat to his position the Brahmin made the new ideas his own in an effort at survival. For instance, prior to the appearance of the Jain-Buddhist heresies, Brahmins ate meat, including beef, and drank liquor. But after the Jain-Buddhist challenge Brahmins became vegetarians and teetotallers.

- Achaya 1994, p. 31–35.

- Achaya 1994, p. 53–55.

- Staples 2020, p. 38–40.

- Rosen 2020, p. 396.

- Bryant 2006, p. 195–196: "At the same time, preliminary signs of tension or unease with such slaughter are occasionally encountered even in the earlier Vedic period. As early as the Ṛgveda, sensitivity is shown toward the slaughtered beasts; for example, one hymn notes that mantras are chanted so that the animal will not feel pain and will go to heaven when sacrificed. The Sāmaveda says: "we use no sacrificial stake, we slay no victims, we worship entirely by the repetition of sacred verses." In the Taittiriīya Āraṇyaka, although prescriptions for offering a cow at a funeral procession are outlined in one place, this is contradicted a little further in the same text where it is specifically advised to release the cow in this same context, rather than kill her. Such passages hint, perhaps, at proto-tensions with the gory brutality of sacrificial butchery, and fore-run the transition between animals as objects and animals as subjects.".

- Tähtinen, Unto (1976). Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition. London. pp. 2–3 (English translation: Schmidt p. 631). ISBN 0-09-123340-2.

- Bryant 2006, p. 196–197.

- Patrick Olivelle (1991). "From feast to fast: food and the Indian Ascetic". In Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld; Julia Leslie (eds.). Medical Literature from India, Sri Lanka, and Tibet. BRILL. pp. 17–36. ISBN 978-9004095229.

- Kane, History of the Dharmaśāstras Vol. 2, p. 762

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 139-141

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, page 122

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 279-280

- Acharya, KT (2003). The Story of Our Food. Universities Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-8173712937.

- Bryant 2006, p. 198–199.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1973). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL Academic. pp. 156–157. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- Krishna, Nanditha (2017). Hinduism and Nature. New Delhi: Penguin Random House. p. 264. ISBN 978-93-8732-654-5.

- Meenakshi Sundaram, T. P. (1957). "Vegetarianism in Tamil Literature". 15th World Vegetarian Congress 1957. International Vegetarian Union (IVU). Retrieved 17 April 2022.

Ahimsa is the ruling principle of Indian life from the very earliest times. ... This positive spiritual attitude is easily explained to the common man in a negative way as "ahimsa" and hence this way of denoting it. Tiruvalluvar speaks of this as "kollaamai" or "non-killing."

- Tirukkuṛaḷ see Chapter 95, Book 7

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Translated by V.V.R. Aiyar, Tirupparaithurai: Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam (1998)

- Sundaram, P. S. (1990). Tiruvalluvar Kural. Gurgaon: Penguin. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-14-400009-8.

- "Russell Simmons on his vegan diet, Obama and Yoga". Integral Yoga Magazine. Integral Yoga Magazine. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Bryant 2006, p. 199–202.

- Sopher, David E. “Pilgrim Circulation in Gujarat.” Geographical Review, vol. 58, no. 3, 1968, pp. 392–425. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/212564. Accessed 24 Sep. 2022

- Desai, A., 2008. Subaltern vegetarianism: witchcraft, embodiment and sociality in Central India. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 31(1), pp.96-117.

- Jaffrelot, C., 2000. Sanskritization vs. Ethnicization in India: Changing indentities and caste politics before mandal. Asian Survey, 40(5), pp.756-766.

- Corichi, Manolo (8 July 2021). "Eight-in-ten Indians limit meat in their diets, and four-in-ten consider themselves vegetarian". Pew Research Center.

- Madhulika Khandelwal (2002), Becoming American, Being Indian, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801488078, pages 38-39

- Steven Rosen, Essential Hinduism, Praeger, ISBN 978-0275990060, page 187

- N Lepes (2008), The Bhagavad Gita and Inner Transformation, Motilal Banarsidass , ISBN 978-8120831865, pages 352-353

- Michael Keene (2002), Religion in Life and Society, Folens Limited, p. 122, ISBN 978-1-84303-295-3, retrieved May 18, 2009

- Paul Insel (2013), Discovering Nutrition, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, ISBN 978-1284021165, page 231

- Tähtinen, Unto: Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London 1976, p. 107-109.

- Mahabharata 12.257 (note that Mahabharata 12.257 is 12.265 according to another count); Bhagavad Gita 9.26; Bhagavata Purana 7.15.7.

- Mahabharata 13.116.37-41

- Sanford, A Whitney."Gandhi's agrarian legacy: practicing food, justice, and sustainability in India". Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 7 no 1 Mr 2013, p 65-87.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2004), Intercultural Education: Ethnographic and Religious Approaches, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845190347, pages 25-27

- J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: L-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- B. V. Bhanu (2004). People of India: Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan. p. 851. ISBN 978-81-7991-101-3.

- Narayanan, Vasudha. “The Hindu Tradition”. In A Concise Introduction to World Religions, ed. Willard G. Oxtoby and Alan F. Segal. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

- Williams, Raymond. An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. 1st. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 159

- Bansi Pandit (2001). The Hindu Mind: Fundamentals of Hindu Religion and Philosophy for All Ages. p. 156. ISBN 9788178220079.

- CHAKRAVARTI, A.K (2007). "Cultural dimensions of diet and disease in india.". City, Society, and Planning: Society. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-81-8069-460-8.

- "Hindus of South America".

- Ridgwell and Ridgway (1987), Food Around the World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198327288, page 67

- Puskar-Pasewicz, Margaret, ed. (2010). Cultural encyclopedia of vegetarianism. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. p. 40[coastal south-western ]. ISBN 978-0313375569. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Speedy, A.W., 2003. Global production and consumption of animal source foods. The Journal of nutrition, 133(11), pp.4048S-4053S.

- Devi, S.M., Balachandar, V., Lee, S.I. and Kim, I.H., 2014. An outline of meat consumption in the Indian population-A pilot review. Korean journal for food science of animal resources, 34(4), p.507.

- Bhaskarananda, Swami (2002). The Essentials of Hinduism. Seattle: The Vedanta Society of Western Washington. p. 60. ISBN 978-1884852046.

- "Victory! Animal Sacrifice Banned at Nepal's Gadhimai Festival, Half a Million Animals Saved". July 28, 2015.

- "Did Nepal temple ban animal sacrifice festival?". July 31, 2015 – via www.bbc.com.

- Hays, Jeffrey. "CHAM | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com.

- "Selected Groups in the Republic of Vietnam: The Cham". www.ibiblio.org.

- "Why Hindus do not eat Non Vegetarian Food on particular days?". WordZz. September 10, 2016.

- Samanta, S. (1994). The “Self-Animal” and Divine Digestion: Goat Sacrifice to the Goddess Kālī in Bengal. The Journal of Asian Studies, 53(3), 779-803. doi:10.2307/2059730

- Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech, 2014, The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies

- Chitrita Banerji, 2010, Eating India: Exploring the Food and Culture of the Land of Spices.

- Subhakanta Behera, 2002, Construction of an identity discourse: Oriya literature and the Jagannath lovers (1866-1936), p140-177.

- Susan Pattinson, 2011, The Final Journey: Complete Hospice Care for the Departing Vaishnavas, pp.220.

- Samanta, S. (1994). The “Self-Animal” and Divine Digestion: Goat Sacrifice to the Goddess Kālī in Bengal. The Journal of Asian Studies, 53(3), 779-803. doi:10.2307/2059730

- Ferro-Luzzi, G. Eichinger. “Food for the Gods in South India: An Exposition of Data.” Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie 103, no. 1 (1978): 86–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25841633.

- Babb, L. A. (1975). The divine hierarchy: Popular Hinduism in central India. Columbia University Press.pages=137-139

- Engfer, L (2004). Desserts around the world. Lerner Publications. p. 12. ISBN 9780822541653.

- Taylor Sen, Colleen (2014). Feasts and Fasts A History of Indian Food. London: Reaktion Books. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78023-352-9. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- Dalal 2010, p. 6.

- Arnott, Margaret L. (1975). Gastronomy : the anthropology of food and food habitys. The Hague: Mouton. p. 319. ISBN 978-9027977397. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Walker, ed. by Harlan (1997). Food on the move : proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1996, [held in September 1996 at Saint Antony's College, Oxford]. Devon, England: Prospect Books. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-907325-79-6. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Amaranth: Modern Prospects for an Ancient Crop. National Academies. 1984. p. 6. ISBN 9780309324458. NAP:14295.

- Dalal 2010, p. 7.

- Dalal 2010, p. 63.

Bibliography

- Achaya, K. T. (1994). Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford University Press.

- Bryant, Edwin (2006). "Strategies of Vedic Subversion: The Emergence of Vegetarianism in Post-Vedic India". In Waldau, Paul; Patton, Kimberly Christine (eds.). A Communion of Subjects: Animals in Religion, Science, and Ethics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50997-8. OCLC 144569913.

- Rosen, Steven J. (2020). "Vaishnav Vegetarianism". In Narayanan, Vasudha (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Materiality (First ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-68832-8. OCLC 1158591615.

- Sen, Colleen Taylor (2014). "Hinduism and Food". In Thompson, Paul B.; Kaplan, David M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-0929-4.

- Staples, James (2020). Sacred Cows and Chicken Manchurian. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74789-7. OCLC 1145911567.

- Srinivas, M.N. (1984). "Some reflections on the nature of caste hierarchy". Contributions to Indian Sociology. SAGE Publications. 18 (2): 151–167. doi:10.1177/006996678401800201. ISSN 0069-9667.