Vernon Sturdee

Lieutenant General Sir Vernon Ashton Hobart Sturdee, KBE, CB, DSO (16 April 1890 – 25 May 1966) was an Australian Army commander who served two terms as Chief of the General Staff. A regular officer of the Royal Australian Engineers who joined the Militia in 1908, he was one of the original Anzacs during the First World War, participating in the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. In the campaign that followed, he commanded the 5th Field Company, before going on to lead the 8th Field Company and the 4th Pioneer Battalion on the Western Front. In 1918 he was seconded to General Headquarters (GHQ) British Expeditionary Force as a staff officer.

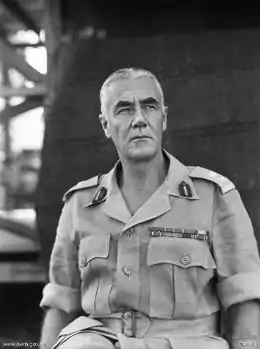

Sir Vernon Ashton Hobart Sturdee | |

|---|---|

Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, GOC First Army c. 1945 | |

| Born | 16 April 1890 Frankston, Victoria |

| Died | 25 May 1966 (aged 76) Heidelberg, Victoria |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ | Australian Army |

| Years of service | 1908–1950 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Service number | NX35000 |

| Commands held | First Army (1944–45) Chief of the General Staff (1940–42, 1946–50) 8th Division (1940) Eastern Command (1939–40) 2nd Military District (1939–40) 5th Divisional Engineers (1917–18) 4th Pioneer Battalion (1917) 8th Field Company (1915–16) |

| Battles/wars | First World War

Second World War

|

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire Companion of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order Mentioned in Despatches (3) |

| Relations | Sir Doveton Sturdee, 1st Baronet (uncle) Sir Charles Merrett (uncle) |

Promotion was stagnant between the wars, and Sturdee remained at his wartime rank of lieutenant colonel until 1935. He served in a series of staff posts, and attended the Staff College at Quetta in British India and the Imperial Defence College in Britain. Like other regular officers, he had little faith in the government's "Singapore strategy", and warned that the Army would have to face an effective and well-equipped Japanese opponent.

Ranked colonel at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Sturdee was raised to lieutenant general in 1940 and became Chief of the General Staff. He proceeded to conduct a doomed defence of the islands to the north of Australia against the advancing Japanese forces. In 1942, he successfully advised the government to divert the Second Australian Imperial Force troops returning from the Middle East to Australia. He then became head of the Australian Military Mission to Washington, D.C., where he represented Australia before the Combined Chiefs of Staff. As commander of the First Army in New Guinea in 1944–45, Sturdee directed the fighting at Aitape, and on New Britain and Bougainville. He was charged with destroying the enemy when opportunity presented itself, but had to do so with limited resources, and without committing his troops to battles that were beyond their strength.

When the war ended, Sturdee took the surrender of Japanese forces in the Rabaul area. As one of the Army's most senior officers, he succeeded General Sir Thomas Blamey as Commander in Chief of the Australian Military Forces in December 1945. He became the Chief of the General Staff a second time in 1946, serving in the post until his retirement in 1950. During this term, he had to demobilise the wartime Army while fielding and supporting the Australian contingent of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan. He developed a structure for the post-war Army that included regular combat formations. As a result, the Australian Regular Army was formed, laying the foundations for the service as it exists today.

Education and early life

Vernon Ashton Hobart Sturdee was born in Frankston, Victoria, on 16 April 1890, the son of Alfred Hobart Sturdee and his wife Laura Isabell, née Merrett.[1] Alfred Sturdee, a medical practitioner from England, came from a prominent naval family and was the brother of Doveton Sturdee, who later became an admiral of the fleet. Alfred emigrated to Australia in the 1880s, travelling as a ship's doctor.[2] He served in the Boer War, where he was mentioned in despatches after he rode under fire to a donga near the enemy's position to aid wounded men.[3] Re-enlisting in the Australian Army Medical Corps as a captain in January 1905, he was promoted to major in August 1908 and lieutenant colonel in December 1912.[2] He later commanded the 2nd Field Ambulance at Gallipoli and, with the rank of colonel, was Assistant Director of Medical Services of the 1st Division on the Western Front.[4][5] He received three more mentions in despatches and was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.[6] His Australian-born wife Laura, known as Lil, was the sister of Charles Merrett, a prominent businessman and Militia officer. Her half-brother, Colonel Harry Perrin, was another Militia officer.[2]

Vernon Sturdee was educated at Melbourne Grammar School, before being apprenticed to an engineer at Jaques Brothers, Richmond, Victoria.[1] Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers, the Militia's engineer component, on 19 October 1908, he was promoted to lieutenant in the Royal Australian Engineers, as the permanent component was then known, on 1 February 1911.[7][8] He married Edith Georgina Robins on 4 February 1913 at St Luke's Church of England, North Fitzroy, Melbourne.[1]

First World War

Gallipoli

Sturdee joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 25 August 1914 with the rank of lieutenant. He was promoted to captain on 18 October,[7] and appointed adjutant of the 1st Division Engineers.[9] He embarked from Melbourne for Egypt on the former P&O ocean liner RMS Orvieto on 21 October 1914.[10] He participated in the landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915,[11] disembarking from the transport SS Minnewaska before 9:00.[12] His duties included supervising the engineer stores park on the beach at Anzac Cove,[11] as well as the construction of jam tin grenades.[12] He was evacuated twice for hospital treatment for enteric fever and for serious damage to his stomach lining from internal burns as a result of too much "Condy's crystals" disinfectant being put into drinking water. As a result, he was to suffer stomach problems for the rest of his life.[13] In July, Sturdee contracted influenza and was evacuated from Anzac Cove.[1]

Sturdee was promoted to major on 28 August 1915,[7] and in September assumed command of the 5th Field Company, a unit raised in Egypt to support the newly formed 2nd Division.[14] From then until the end of the campaign, he was responsible for all engineering and mining work at Steele's, Quinn's and Courtney's Posts,[11] three of the northernmost and most dangerous and exposed parts of the line.[15] He departed Anzac Cove for the last time on 17 December 1915, two days before the final evacuation.[16]

Western Front

On returning to Egypt after the evacuation of Anzac, Sturdee assumed responsibility for the provision of hutting at the AIF reinforcement camp at Tel el Kebir.[11] There was already another 5th Field Company in Egypt, which had been raised in Australia. Accordingly, Sturdee's 5th Field Company was renumbered 8th, and assigned to the 5th Division when it was formed in February 1916. This move gave the new division an experienced field company, but at the expense of items of the company's mail going to France for a time and arriving back in Egypt marked "Not Fifth, try Eighth."[17]

The 5th Division moved to France in June 1916, where it participated in the disastrous Battle of Fromelles in July. During the action, Sturdee's 8th Field Company supported the 8th Infantry Brigade. A trench dug by the former facilitated the latter's withdrawal across no man's land.[11] For his service at Gallipoli and Fromelles, he was mentioned in despatches,[18] and awarded the Distinguished Service Order.[19] Heavy losses in the fighting at Fromelles prevented the 5th Division from participating in the Battle of the Somme. To free up another division to participate, II ANZAC Corps organised "Franks Force" to take over a divisional frontage in the Houplines sector, and Sturdee became its Commander Royal Engineers (CRE).[20] When the 5th Division finally moved to the Somme sector in November, he became CRE in charge of the road from Albert to Montauban.[21]

On 13 February 1917, Sturdee was appointed to command the 4th Pioneer Battalion, with the rank of lieutenant colonel.[7] Pioneer battalions were organised as infantry but contained a high percentage of tradesmen and were employed on construction tasks under engineer supervision. Over the next nine months the 4th Pioneer Battalion maintained roads, built camps, laid cables and dug trenches and dugouts.[1] By 1917, the Australian government was pushing strongly for British Army officers holding Australian commands and staff posts to be replaced by Australians. As part of this "Australianisation" of the Australian Corps, Sturdee became CRE of the 5th Division on 25 November 1917, replacing a British Army officer.[22] On 27 March 1918, Sturdee was seconded to General Headquarters (GHQ) British Expeditionary Force as a staff officer, remaining there until 22 October 1918.[7] This provided a rare opportunity, for an Australian officer, of observing the workings of a major headquarters engaged in active operations.[1] For his service on the Western Front, Sturdee was mentioned in despatches a second time,[23] and appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for his work at GHQ.[24]

Between the wars

Sturdee embarked for Australia on 16 November 1918,[25] and his AIF appointment was terminated on 14 March 1919.[1] He was entitled to his AIF rank of lieutenant colonel as an honorary rank, but his substantive rank was still only that of a captain. He was given the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel on 1 January 1920, but this did not become substantive until 1 April 1932. Sturdee initially served as Senior Engineer Officer on the staff of the 3rd Military District at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne. In 1921, he attended the Staff College at Quetta in British India. He was an instructor in military engineering and surveying at the Royal Military College, Duntroon from 16 February to 31 December 1924, before returning to Melbourne to serve on the staff of the 4th Division until 26 March 1929. Posted to the United Kingdom, he served at the War Office and attended the Imperial Defence College in 1931. From 1 January 1931 to 31 December 1932, he was the military representative at the High Commission of Australia in London.[7]

Sturdee was Director of Military Operations and Intelligence at Army Headquarters in Melbourne from 14 February 1933 to 1 March 1938, a period "when the Army was at rock bottom",[26] and then served as Director of Staff Duties until 12 October 1938. He was given the brevet rank of colonel on 1 July 1935; this became temporary on 1 July 1936 and finally substantive on 1 July 1937, over twenty years after he had become a lieutenant colonel in the AIF.[7] He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the New Year Honours in 1939 for his services on the Army Headquarters staff.[27]

Like his predecessor as Director of Military Operations and Intelligence, Colonel John Lavarack, and many other officers, Sturdee had little faith in the government's "Singapore strategy", which aimed to deter Japanese aggression through the presence of a powerful British fleet based at Singapore.[28] In 1933, Sturdee told senior officers that the Japanese

would all be regulars, fully trained and equipped for the operations, and fanatics who like dying in battle, whilst our troops would consist mainly of civilians hastily thrown together on mobilisation with very little training, short of artillery and possibly of gun ammunition.[29]

Second World War

Defence of Australia

In 1939, the Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General Ernest Squires, implemented a reorganisation of the Army in which the old military districts were replaced by larger commands led by lieutenant generals.[30] On 13 October 1939, Sturdee was promoted from colonel to lieutenant general and assumed control of the new Eastern Command.[31] He had to supervise the raising, training and equipping of the new Second Australian Imperial Force units being formed in New South Wales, as well as the now-conscript Militia.[1]

On 1 July 1940, Sturdee accepted a demotion to major general in order to become the commander of Second AIF's newly raised 8th Division, receiving the Second AIF serial number NX35000.[32] His period in this command was brief. On 13 August 1940, the Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Brudenell White, was killed in the Canberra air disaster. Sturdee was restored to his rank of lieutenant general and appointed Chief of the General Staff.[33] As such, he was responsible for the training and maintenance of the AIF in the Middle East and the Far East—although not their operational control—and for the administration and training of the Militia.[34]

As the prospect of war with Japan became more likely, so also did the need to make appropriate arrangements for leading the defence of Australia. In 1935, Lavarack had recommended that in the event of war, the Military Board be abolished and its powers vested in a Commander-in-chief. In April 1941, the Minister for the Army, Percy Spender, recommended that this now be done, with Sturdee becoming Commander in Chief of the Australian Military Forces. Instead, the government elected to adopt the British system, in which the Military Board (or Army Council as it was called there) continued to operate, with a separate GOC Home Forces. On 5 August 1941, Major General Sir Iven Mackay was appointed to this newly created post.[35] However, the idea of a Commander in Chief did not go away and editorials in the Sunday Telegraph and The Sydney Morning Herald advocated the appointment.[36]

East Indies campaign

Sturdee attempted to defend the islands to the north of Australia to satisfy an allied agreement made during the second Four-Power Staff Conference at Singapore on 22 February 1941.[37] With only one AIF infantry brigade available, the 23rd, he could only afford to protect the islands most strategically important to the defence of Australia. He sent Gull Force centred on the 2/21st Infantry Battalion to Ambon,[38] Lark Force centred on the 2/22nd to Rabaul,[39] and Sparrow Force centred on the 2/40th Infantry Battalion with 2/2nd Independent Company to Timor.[40]

Sturdee knew that their prospects were slim at best but the was required to secure Dutch support for the defence of the region. He expected them "to put up the best possible defence" with what resources they had, and hopefully slow the Japanese advance to allow time for reinforcements to arrive. When there were doubts about the morale of one commander, Sturdee replaced him with a staff officer from Army Headquarters who volunteered for the position despite being well aware of the odds.[41] All the garrisons were overrun after a spirited defence, except for the 2/2nd Independent Company, which managed to hold on in East Timor.[42]

After the war Sturdee described the situation thus:

I realised at the time [in 1941–42] that these forces [on Rabaul,Timor and Ambon] would be swallowed up ... but these garrisons were the smallest self-contained units then in existence. My only regret now looking back was that we didn't have more knowledge of the value of Independent Companies, at that time they were only in the hatching stage and their value unknown. I am now certain that they would have been the answer, and at no time did I consider that additional troops and arms should be sent to these potentially beleaguered garrisons, as it would only put more [men] in the [prisoner-of-war] bag.[43]

Commenting on Sturdee's forward defence strategy after the war, Colonel Eustace Graham Keogh wrote:

Taking the prevailing circumstances into full account, it is hard to justify the detachments at Ambon and Rabaul. Neither place was a vital link in the defences or communications. Certainly it was highly desirable to deny the enemy access to them, but once command of the sea had been lost any forces stationed at those places could not be supported until the navy situation had been restored. In neither case was the force anything like strong enough to survive for the required length of time, or even to impose delay on the powerful forces the enemy was employing. It is true that the arrangements for the despatch of these forces were made before Japan struck, before the strength of the blows she would deliver had been appreciated. But after her probable course of action and her methods had been amply demonstrated there was still time to reconsider the situation. Despite this demonstration, it would appear that Army Headquarters persisted in believing that these lone battalions could impose delay on the enemy. Consequently the maxim, enunciated it is believed by one of the early Pharaohs, operated in full– "Detachments beyond effective supporting distance usually get their heads cut off." There are, of course, occasions when something worthwhile can be gained by the sacrifice of a detachment. This was not one of them.[44]

In a 2010 PhD thesis on Ambon, David Evans attacked Sturdee as incompetent.[45] A more balanced appraisal was written by Michael Evans in 2000:

At this time, Sturdee and his colleagues were faced with critical decisions in the face of a swift and unrelenting tide of Japanese success—a success that seemed to herald an imminent invasion of Australia. Under these circumstances, that the Chiefs of Staff sought, at high cost, to keep the Japanese military juggernaut as far as possible from Australian soil should be no great surprise. The Chiefs of Staff recommended a change of strategy only when there was irrefutable evidence of military failure to place before the War Cabinet. Such a stance was consistent with both the turbulent political climate in Australia and the realities of coalition warfare that prevailed in early 1942... If there is a villain in the tragedy of Ambon in 1942, it is a "ghost in the machine' that can be found in the systemic crisis of Australian defence in 1941–42—a crisis caused by twenty years of neglect of defence by a succession of governments and by the electorate they served."[46]

In February 1942, on advice from Lavarack that the Dutch East Indies would soon fall, Sturdee urged the Australian government that the 17,800 troops returning from the Middle East, originally bound for Java, be diverted to Australia. Sturdee contended that Java could not be held, and that Allied resources should instead be concentrated in an area from which an offensive could be launched. The best place for this, he argued, was Australia. When Prime Minister John Curtin backed his Chief of the General Staff, it brought him into conflict with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who suggested that the AIF be diverted to Burma. In the end, Curtin won his point, and subsequent events vindicated Sturdee's appreciation of the situation.[47] Official historian Lionel Wigmore concluded:

It is now evident that the 7th Division would have arrived only in time to help in the extraction from Pegu and to take part in the long retreat to India. In that event it could not have been returned to Australia, rested and sent to New Guinea in time to perform the crucial role it was to carry out in the defeat of the Japanese offensive which would open there in July 1942. The Allied cause therefore was well served in sound judgement and solid persistence of General Sturdee who maintained his advice against that of the Chiefs of Staff in London and Washington.[48]

Island campaigns

In March 1942, the Military Board was abolished and General Sir Thomas Blamey was appointed Commander in Chief.[49] Blamey decided that after the hectic events of the previous months, Sturdee needed a rest and appointed him as Head of the Australian Military Mission to Washington, D.C., where the war's strategy was now being decided. Sturdee accepted on condition that after a year's duty in Washington he would be appointed to an important command.[50] In Washington, Sturdee represented Australia before the Combined Chiefs of Staff and managed to obtain the right of direct access to the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General George Marshall.[1] For his services as Chief of the General Staff, Sturdee was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath on 1 January 1943.[51]

Sturdee returned to Australia and assumed command of the First Army on 1 March 1944.[7] His headquarters was initially located in Queensland, but on 2 October 1944 it commenced operations in Lae, and Sturdee assumed command of the troops in New Guinea. These included Lieutenant General Stanley Savige's II Corps, with its headquarters at Torokina on Bougainville; Major General Alan Ramsay's 5th Division on New Britain; Major General Jack Stevens' 6th Division at Aitape; and the 8th Infantry Brigade west of Madang. On 18 October, Blamey issued an operational instruction that defined the role of the First Army: "by offensive action to destroy enemy resistance as opportunity offers without committing major forces."[52]

Sturdee was concerned by this order's ambiguity and sought clarification from Blamey. The Commander in Chief responded by stating that "my conception is that action must be of a gradual nature" involving the use of patrols to determine Japanese strengths and positions before large offensives were undertaken.[53] The situation on New Britain was straightforward enough; the enemy was known to be stronger than the Australian forces there—although it was not realised just how much stronger—and so the best that could be done was to eliminate small numbers of Japanese troops by aggressive patrolling.[54] At Aitape, Stevens was tasked on the one hand with pushing the Japanese back far enough to protect the airfields;[55] but on the other, with not allowing the 6th Division to become heavily engaged since it might be required for use elsewhere. On Bougainville, Savige had the strength and ability to conduct a major campaign, but Blamey counselled caution.[52]

Juggling a number of contradictory requirements, Sturdee had to conduct three widely separated campaigns, the Aitape–Wewak campaign, the New Britain campaign and the Bougainville Campaign, and do so with limited resources. Shipping, which was controlled by General Douglas MacArthur's GHQ South West Pacific Area, was a source of "continual anxiety".[56] On 18 July 1945, Sturdee wrote to Savige:

We are on rather a hair trigger with operations in Bougainville and in 6 Division area in view of the political hostility of the Opposition and the Press criticism of the policy of operations being followed in these areas. The general policy is out of our hands, but we must conduct our operations in the spirit of the role given us by C. in C. [Blamey], the main essence of which is that we should attain our object with a minimum of Australian casualties. We have in no way been pressed on the time factor and to date have managed to defeat the Japs with very reasonable casualties considering the number of the Japs that have been eliminated.[57]

Sturdee's operations were effective. On Bougainville, at a cost of 516 Australian dead and 1,572 wounded, Savige's troops had occupied much of the island and killed 8,500 Japanese; another 9,800 died from malnutrition and disease.[58] On New Britain, where 74 Australians died and 140 were wounded, the heavily outnumbered 5th Division had overrun central New Britain.[59] Meanwhile, the 6th Division at Aitape and Wewak had lost 442 dead and 1,141 wounded while clearing the Japanese from the coast and driving them into the mountains, killing 9,000 and taking 269 prisoners.[60]

On 6 September 1945, Sturdee received the surrender of Japanese forces in the First Army area from General Hitoshi Imamura, the commander of the Japanese Eighth Area Army, and Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, the commander of the South East Area Fleet, in a ceremony held on the deck of the British aircraft carrier HMS Glory at Rabaul. The two Japanese swords handed over in the surrender ceremony, together with the sword worn by Sturdee, which was his father's, were presented to the Australian War Memorial by Lady Sturdee in 1982.[61] For his service in the final campaigns, Blamey recommended Sturdee for a knighthood,[62] but this was reduced to a third mention in despatches.[63]

Later life

In November 1945, the Minister for the Army, Frank Forde, informed Blamey that the government had decided to re-establish the Military Board and he should therefore vacate his office. Sturdee became acting Commander in Chief on 1 December 1945. On 1 March 1946, the post of Commander in Chief was abolished and Sturdee became Chief of the General Staff again.[64] There was much work to be done; the wartime Army had a strength of 383,000 in August 1945, of whom 177,000 were serving outside Australia.[65]

These troops had to be demobilised, but what should replace the wartime Army had not yet been determined. Sturdee and his Vice Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell, had to develop an appropriate structure. The proposal submitted to Cabinet called for national service, a regular army of 33,000 and reserves of 42,000, but the government baulked at the £20m per annum price tag. A smaller force of 19,000 regulars and 50,000 reservists at a cost of £12.5m per annum was finally approved in 1947.[66] Conditions of service were also overhauled.[67]

At the same time, the Army had to handle huge stockpiles of equipment, stores and supplies. Some were far in excess of the Army's needs and had to be disposed of. Hospitals still had to be run, although some were transferred to the Department of Repatriation. The Army had to maintain its schools and training establishments. Moreover, the Army had to field and maintain part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan.[68] Over next fifty years, operations would be conducted by the new Australian Regular Army that Sturdee created, rather than the Militia or specially enlisted expeditionary forces.[69]

Sturdee retired on 17 April 1950. In recognition of his services, he was created a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire on 1 January 1951.[70] In retirement, he continued to live in Kooyong, Melbourne. He became a director of the Australian arm of Standard Telephones and Cables and was honorary colonel of the Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers from 1951 to 1956. The Army named the Landing Ship Medium Vernon Sturdee after him. He died on 25 May 1966 at the Repatriation General Hospital, Heidelberg. He was accorded a funeral with full military honours, and cremated.[1] Lieutenant General Sir Edmund Herring, a boyhood friend from Melbourne Grammar, was principal pall bearer.[71] Sturdee was survived by his wife, their daughter and one of their two sons. Before he died, he burned all his private papers. "I have done the job," he said. "It is over."[1]

Notes

- Wood 2002, pp. 340–342

- Buckley 1990, p. 32

- "No. 27331". The London Gazette. 1 July 1901. p. 4554. (Alfred Sturdee – MID)

- Butler et al. 1930, p. 826

- Butler 1940, p. 29

- "Honours and Awards – Sturdee, Alfred Hobart". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- AMF Army List of Officers, October 1950

- McNicoll 1979, pp. 8–11

- McNicoll 1979, p. 19

- First World War Embarkation Roll – Vernon Ashton Hobart Sturdee, Australian War Memorial, retrieved 12 December 2009

- Honours and Awards – Vernon Ashton Hobart Sturdee – Distinguished Service Order (PDF), Australian War Memorial, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2015, retrieved 23 November 2009

- Buckley 1990, p. 44

- Buckley 1990, p. 45

- McNicoll 1979, p. 43

- Bean 1924, pp. 46–47

- Buckley 1990, p. 47

- McNicoll 1979, p. 60

- "No. 29890". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 January 1917. p. 254. (MID)

- "No. 29886". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1917. p. 28. (DSO)

- McNicoll 1979, p. 74

- McNicoll 1979, p. 76

- Bean 1937, pp. 14–16

- "No. 31089". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1918. p. 15225. (MID)

- "No. 31092". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 May 1918. p. 13. (OBE)

- First World War Nominal Roll Page – AWM133, 50–093, retrieved 13 December 2009

- Rowell 1974, p. 30

- "No. 34585". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1939. p. 8. (CBE)

- Buckley 1983, p. 30

- Horner 1978, p. 16

- Rowell 1974, p. 40

- Horner 1984, p. 145

- Wigmore 1957, p. 28

- Wigmore 1957, p. 32

- Horner 1978, p. 24

- Horner 1978, pp. 24–25

- Horner 1978, pp. 54–55

- Bussemaker, Herman (28 August 2020). "Australian-Dutch defence cooperation, 1940–1941". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 418–419.

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 394–395.

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 467–468.

- Horner 1984, pp. 152–153.

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 493–494.

- Evans 2000, p. 66.

- Keogh 1965, p. 131.

- Evans 2010, pp. 198–199.

- Evans 2000, pp. 67–68.

- Wigmore 1957, pp. 444–452.

- Wigmore 1957, p. 45.

- Horner 1978, pp. 55–57

- Horner 1978, p. 99

- "No. 35841". The London Gazette. 1 January 1943. p. 3. (CB)

- Long 1963, p. 25

- Charlton 1983, pp. 42–43

- Long 1963, pp. 240–241

- Long 1963, pp. 271–272

- Long 1963, p. 89

- Long 1963, p. 218

- Long 1963, pp. 237–238

- Long 1963, pp. 269–270

- Long 1963, pp. 385–386

- Buckley 1983, p. 37

- Horner 1998, p. 559

- "No. 37898". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 March 1947. p. 1091. (MID)

- Long 1963, p. 579

- Sligo 1997, pp. 29–30

- Sligo 1997, pp. 34–35

- Sligo 1997, pp. 40–42

- Rowell 1974, pp. 160–164

- Sligo 1997, p. 47

- "No. 39105". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1951. p. 36. (KBE)

- Buckley 1990, p. 50

References

- Bean, Charles (1924). Volume II – The Story of ANZAC from 4 May 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 271462380.

- Bean, Charles (1937). Volume V – The Australian Imperial Force in France 1918 during the Main German Offensive 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 9066797.

- Buckley, Colonel J. P. (July–August 1983). "Lieutenant General Sir Vernon Sturdee, KBE, CB, DSO" (PDF). Australian Defence Force Journal. Canberra: Department of Defence (41): 29–42. ISSN 1444-7150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2011.

- Buckley, Colonel J. P. (March–April 1990). "Father and Son on Gallipoli" (PDF). Australian Defence Force Journal. Canberra: Department of Defence (81): 30–53. ISSN 1444-7150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2009.

- Butler, A. G.; Downes, R. M.; Maguire, F. A.; Cilento, R. W. (1930). Volume I – Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 156690674.

- Butler, A. G. (1940). Volume II – The Western Front. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 314726707.

- Charlton, Peter (1983). The Unnecessary War. Island Campaigns of the South-West Pacific 1944–45. South Melbourne: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-35628-4. OCLC 11390387.

- Evans, David A. (2010). The Ambon Forward Observation Line Strategy 1941-1942: A Lesson in Military Incompetence (PDF) (PhD thesis). Murdoch University. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Evans, Michael (2000). "Developing Australia's Maritime Concept Of Strategy: Lessons from the Ambon Disaster of 1942". Study Paper No. 303. Australian Army Research Centre. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Horner, David (1978). Crisis of Command: Australian Generalship and the Japanese Threat 1941–1943. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0-7081-1345-1. OCLC 5103306.

- Horner, David (1984). Horner, David (ed.). Lieutenant-General Sir Vernon Sturdee: The Chief of the General Staff as Commander. The Commanders: Australian Military Leadership in the Twentieth Century. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. pp. 143–158. ISBN 0-86861-496-3. OCLC 11304521.

- Horner, David (1998). Blamey: The Commander-in-Chief. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-734-8. OCLC 39291537.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne: Grayflower Publications.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134176.

- McNicoll, Ronald (1979). Making and Breaking: The Royal Australian Engineers 1902 to 1919. Canberra: Royal Australian Engineers. ISBN 0-9596871-2-2. OCLC 27630527.

- Rowell, Sydney (1974). Full Circle. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84058-2. OCLC 1427892.

- Sligo, Graeme (1997). Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey (eds.). The Development of the Australian Regular Army 1944–1952 (PDF). The Second Fifty Years: The Australian Army 1947–1997. Canberra: University of New South Wales. ISBN 0-7317-0363-4. OCLC 38836125.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219.

- Wood, James (2002). "Sturdee, Sir Vernon Ashton Hobart (1890–1966)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 30 October 2012 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- The Army List of Officers of the Australian Military Forces. Melbourne: Australian Army. 1950.