Vladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych[6] (Old East Slavic: Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь;[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] c. 958 – 15 July 1015), also known as Vladimir the Great or Volodymyr the Great,[8] was Prince of Novgorod, Grand Prince of Kiev, and ruler of Kievan Rus' from 980 to 1015.[9][10]

| Vladimir the Great | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vladimir's effigy on one of his coins. He is crowned in the Byzantine style, holding a cross-mounted staff in one hand and a Khazar-inspired trident[1] in the other. | |||||

| Grand Prince of Kiev | |||||

| Reign | 11 June 980 – 15 July 1015 | ||||

| Coronation | 11 June 980 | ||||

| Predecessor | Yaropolk I of Kiev | ||||

| Successor | Sviatopolk I of Kiev | ||||

| Prince of Novgorod | |||||

| Reign | 969 – c. 977 | ||||

| Predecessor | Sviatoslav I of Kiev | ||||

| Successor | Yaropolk I of Kiev | ||||

| Born | c. 958 Budnik near Pskov (modern Pskov Oblast)[2] or Budiatychi (modern Volyn Oblast)[3] | ||||

| Died | 15 July 1015 (aged approximately 57) Berestove (today a part of Kyiv) | ||||

| Burial | Church of the Tithes, Kyiv | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue among others |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Rurikid | ||||

| Father | Sviatoslav I of Kiev | ||||

| Mother | Malusha[4] | ||||

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity (from 988) prev. Slavic pagan | ||||

Vladimir of Kiev | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prince of Novgorod Grand Prince of Kiev | |

| Born | c. 958 |

| Died | 15 July 1015 |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Catholic Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism[5] |

| Feast | 15 July |

| Attributes | crown, cross, throne |

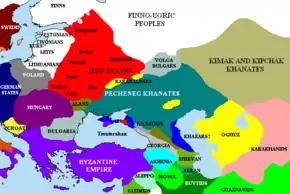

Vladimir's father was Prince Sviatoslav I of Kiev of the Rurikid dynasty.[11] After the death of his father in 972, Vladimir, who was then prince of Novgorod, was forced to flee to Scandinavia in 976 after his brother Yaropolk murdered his other brother Oleg of Drelinia, becoming the sole ruler of Rus'. In Sweden, with the help of his relative Ladejarl Håkon Sigurdsson, ruler of Norway, he assembled a Varangian army and reconquered Novgorod from Yaropolk.[12] By 980, Vladimir had consolidated the Rus realm from modern-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine to the Baltic Sea and had solidified the frontiers against incursions of Bulgarians, Baltic tribes and Eastern nomads. Originally a follower of Slavic paganism, Vladimir converted to Christianity in 988[13][14][15] and Christianized the Kievan Rus'.[11] Due to this act, which fundamentally altered the historical trajectory of the Rus' and led to his declaration as a saint in both Western Christianity and the Eastern Orthodox Church, Vladimir is thus also known as Saint Vladimir or Saint Volodymyr.

Rise to power

Born in 958, Vladimir was the natural son and youngest son of Sviatoslav I of Kiev by his housekeeper Malusha.[16] Malusha is described in the Norse sagas as a prophetess who lived to the age of 100 and was brought from her cave to the palace to predict the future. Malusha's brother Dobrynya was Vladimir's tutor and most trusted advisor. Hagiographic tradition of dubious authenticity also connects his childhood with the name of his grandmother, Olga of Kiev, who was Christian and governed the capital during Sviatoslav's frequent military campaigns.

Transferring his capital to Pereyaslavets in 969, Sviatoslav designated Vladimir ruler of Novgorod the Great but gave Kiev to his legitimate son Yaropolk. After Sviatoslav's death at the hands of the Pechenegs in 972, a fratricidal war erupted in 976 between Yaropolk and his younger brother Oleg, ruler of the Drevlians. In 977, Vladimir fled to his kinsman Haakon Sigurdsson, ruler of Norway, collecting as many Norse warriors as he could to assist him to recover Novgorod. On his return the next year, he marched against Yaropolk. On his way to Kiev he sent ambassadors to Rogvolod (Norse: Ragnvald), prince of Polotsk, to sue for the hand of his daughter Rogneda (Norse: Ragnhild). The high-born princess refused to affiance herself to the son of a bondswoman (and was betrothed to Yaropolk), so Vladimir attacked Polotsk, took Ragnhild by force, and put her parents to the sword.[16][17] Polotsk was a key fortress on the way to Kiev, and capturing Polotsk and Smolensk facilitated the taking of Kiev in 978, where he slew Yaropolk by treachery and was proclaimed knyaz of all Kievan Rus.[18]

Years of pagan rule

Vladimir continued to expand his territories beyond his father's extensive domain. In 981, he seized the Cherven towns from the Poles; in 981–982, he suppressed a Vyatichi rebellion; in 983, he subdued the Yatvingians; in 984, he conquered the Radimichs; and in 985, he conducted a military campaign against the Volga Bulgars,[19][20] planting numerous fortresses and colonies on his way.[16]

Although Christianity had spread in the region under Oleg's rule, Vladimir had remained a thoroughgoing pagan, taking eight hundred concubines (along with numerous wives) and erecting pagan statues and shrines to gods.[21]

He may have attempted to reform Slavic paganism in an attempt to identify himself with the various gods worshipped by his subjects. He built a pagan temple on a hill in Kiev dedicated to six gods: Perun—the god of thunder and war, a god favored by members of the prince’s druzhina (military retinue)"; Slav gods Stribog and Dazhd'bog; Mokosh—a goddess representing Mother Nature "worshipped by Finnish tribes"; Khors and Simargl, "both of which had Iranian origins, were included, probably to appeal to the Poliane."[22]

Open abuse of the deities that most people in Rus' revered triggered widespread indignation. A mob killed the Christian Fyodor and his son Ioann (later, after the overall Christianisation of Kievan Rus', people came to regard these two as the first Christian martyrs in Rus', and the Orthodox Church set a day to commemorate them, 25 July). Immediately after the murder of Fyodor and Ioann, early medieval Rus' saw persecutions against Christians, many of whom escaped or concealed their belief.[lower-alpha 3]

However, Prince Vladimir mused over the incident long after, and not least for political considerations. According to the early Slavic chronicle, the Tale of Bygone Years, which describes life in Kievan Rus' up to the year 1110, he sent his envoys throughout the world to assess first-hand the major religions of the time: Islam, Roman Catholicism, Judaism, and Byzantine Orthodoxy. They were most impressed with their visit to Constantinople, saying, "We knew not whether we were in Heaven or on Earth… We only know that God dwells there among the people, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations."[23]

Christianization of the Kievan Rus'

The Primary Chronicle reports that in the year 987, after consultation with his boyars, Vladimir the Great sent envoys to study the religions of the various neighboring nations whose representatives had been urging him to embrace their respective faiths. The result is described by the chronicler Nestor. He reported that Islam was undesirable due to its prohibition of alcoholic beverages and pork.[24] Vladimir remarked on the occasion: "Drinking is the joy of all Rus'. We cannot exist without that pleasure."[24] Ukrainian and Russian sources also describe Vladimir consulting with Jewish envoys and questioning them about their religion, but ultimately rejecting it as well, saying that their loss of Jerusalem was evidence that they had been abandoned by God.

His emissaries also visited pre-schism Latin Rite Christian and Eastern Rite Christian missionaries. Ultimately Vladimir settled on Eastern Christianity. In the churches of the Germans his emissaries saw no beauty; but at Constantinople, where the full festival ritual of the Byzantine Church was set in motion to impress them, they found their ideal: "We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth", they reported, describing a majestic Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia, "nor such beauty, and we know not how to tell of it." Vladimir was impressed by this account of his envoys.[16]

In 988, having taken the town of Chersonesos in Crimea, he boldly negotiated for the hand of emperor Basil II's sister, Anna.[25] Never before had a Byzantine imperial princess, and one "born in the purple" at that, married a barbarian, as matrimonial offers of French kings and German emperors had been peremptorily rejected. In short, to marry the 27-year-old princess to a pagan Slav seemed impossible. Vladimir was baptized at Chersonesos, however, taking the Christian name of Basil out of compliment to his imperial brother-in-law; the sacrament was followed by his wedding to Anna. Returning to Kiev in triumph, he destroyed pagan monuments and established many churches, starting with a church dedicated to St. Basil,[26] and the Church of the Tithes (989).[16]

Arab sources, both Muslim and Christian, present a different story of Vladimir's conversion. Yahya of Antioch, al-Rudhrawari, al-Makin, al-Dimashqi, and ibn al-Athir all give essentially the same account.[27] In 987, Bardas Sclerus and Bardas Phocas revolted against the Byzantine emperor Basil II. Both rebels briefly joined forces, but then Bardas Phocas proclaimed himself emperor on 14 September 987. Basil II turned to the Kievan Rus' for assistance, even though they were considered enemies at that time. Vladimir agreed, in exchange for a marital tie; he also agreed to accept Christianity as his religion and to Christianize his people. When the wedding arrangements were settled, Vladimir dispatched 6,000 troops to the Byzantine Empire, and they helped to put down the revolt.[28]

In 988 and 991, he baptized Pecheneg princes Metiga and Kuchug, respectively.[29]

Christian reign

Vladimir then formed a great council out of his boyars and set his twelve sons over his subject principalities.[16] According to the Primary Chronicle, he founded the city of Belgorod in 991. In 992, he went on a campaign against the Croats, most likely the White Croats that lived on the border of modern Ukraine. This campaign was cut short by the attacks of the Pechenegs on and around Kyiv.

In his later years he lived in a relative peace with his other neighbors: Bolesław I of Poland, Stephen I of Hungary, and Andrikh the Czech (a questionable character mentioned in A Tale of the Bygone Years). After Anna's death, he married again, likely to a granddaughter of Otto the Great.

In 1014, his son Yaroslav the Wise stopped paying tribute. Vladimir decided to chastise the insolence of his son and began gathering troops against him. Vladimir fell ill, however, most likely of old age, and died at Berestove, near modern-day Kyiv. The various parts of his dismembered body were distributed among his numerous sacred foundations and were venerated as relics.[16]

During his Christian reign, Vladimir lived the teachings of the Bible through acts of charity. He would hand out food and drink to the less fortunate, and made an effort to go out to the people who could not reach him. His work was based on the impulse to help one's neighbors by sharing the burden of carrying their cross.[30] He founded numerous churches, including the Desyatinnaya Tserkov (Church, or Cathedral, of the Tithes) (989), established schools, protected the poor and introduced ecclesiastical courts. He lived mostly at peace with his neighbors, the incursions of the Pechenegs alone disturbing his tranquility.[16]

He introduced the Byzantine law code into his territories following his conversion but reformed some of its harsher elements; he notably abolished the death penalty along with judicial torture and mutilation.[31]

Family

The fate of all Vladimir's daughters, whose number is around nine, is uncertain. His wives, concubines, and their children were as follows:

- Olava or Allogia (Varangian or Czech), speculative; she might have been mother of Vysheslav while others claim that it is a confusion with Helena Lekapene

- Vysheslav (c. 977 – c. 1010), Prince of Novgorod (988–1010)

- a widow of Yaropolk I, a Greek nun

- Sviatopolk the Accursed (born c. 979), possibly the surviving son of Yaropolk

- Rogneda (the daughter of Rogvolod); later upon divorce she entered a convent taking the Christian name of Anastasia

- Izyaslav of Polotsk (born c. 979, Kiev), Prince of Polotsk (989–1001)

- Yaroslav the Wise (no earlier than 983), Prince of Rostov[32] (988–1010), Prince of Novgorod (1010–1034), Grand Prince of Kiev (1016–1018, 1019–1054). Possibly he was a son of Anna rather than Rogneda. Another interesting fact is that he was younger than Sviatopolk according to the words of Boris in the Tale of Bygone Years and not as it was officially known.

- Vsevolod (c. 984 – 1013), possibly the Swedish Prince Wissawald of Volhynia (c. 1000), was perhaps the first husband of Estrid Svendsdatter

- Mstislav, distinct from Mstislav of Chernigov, possibly died as an infant, if he was ever born

- Mstislav of Chernigov (born c. 983), Prince of Tmutarakan (990–1036), Prince of Chernigov (1024–1036), other sources claim him to be the son of other mothers (Adela, Malfrida, or some other Bulgarian wife)

- Predslava, a concubine of Bolesław I Chrobry according to Gesta principum Polonorum

- Premislava, (died 1015), some sources state that she was a wife of the Duke Laszlo (Vladislav) "the Bald" of the Arpadians

- Mstislava, in 1018 was taken by Bolesław I Chrobry among the other daughters

- Bulgarian Adela, some sources claim that Adela is not necessarily Bulgarian as Boris and Gleb may have been born from some other wife

- Boris (born c. 986), Prince of Rostov (c. 1010 – 1015), remarkable is the fact that the Rostov Principality as well as the Principality of Murom used to border the territory of the Volga Bolgars

- Gleb (born c. 987), Prince of Murom (1013–1015), as is Boris, Gleb is also claimed to be the son of Anna Porphyrogenita

- Stanislav (born c. 985 – 1015), Prince of Smolensk (988–1015), possibly of another wife and the fate of whom is not certain

- Sudislav (died 1063), Prince of Pskov (1014–1036), possibly of another wife, but he is mentioned in Nikon's Chronicles. He spent 35 years in prison and later became a monk.

- Malfrida

- Sviatoslav (c. 982 – 1015), Prince of Drevlians (990–1015)

- Anna Porphyrogenita

- Theofana, a wife of Novgorod posadnik Ostromir, a grandson of semi-legendary Dobrynya (highly doubtful is the fact of her being Anna's offspring)

- a granddaughter of Otto the Great (possibly Rechlinda Otona [Regelindis])

- Maria Dobroniega of Kiev (born c. 1012), the Duchess of Poland (1040–1087), married around 1040 to Casimir I the Restorer, Duke of Poland, her maternity as daughter of this wife is deduced from her apparent age

- other possible family

- Vladimirovna, an out-of-marriage daughter (died 1044), married to Bernard, Margrave of the Nordmark.

- Pozvizd (born prior to 988), a son of Vladimir according to Hustyn Chronicles. He, possibly, was the Prince Khrisokhir mentioned by Niketas Choniates.

Significance and legacy

The Eastern Orthodox, Byzantine Rite Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches celebrate the feast day of St. Vladimir on 15/28 July.[33][34]

The town Volodymyr in north-western Ukraine was founded by Vladimir and is named after him.[35] The foundation of another town, Vladimir in Russia, is usually attributed to Vladimir Monomakh. However some researchers argue that it was also founded by Vladimir the Great.[36]

St Volodymyr's Cathedral, one of the largest cathedrals in Kyiv, is dedicated to Vladimir the Great, as was originally the Kyiv University. The Imperial Russian Order of St. Vladimir and Saint Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary in the United States are also named after him.

The memory of Vladimir was also kept alive by innumerable Russian folk ballads and legends, which refer to him as Krasno Solnyshko (the Fair Sun, or the Red Sun; Красно Солнышко in Russian). The Varangian period of Eastern Slavic history ceases with Vladimir, and the Christian period begins. The appropriation of Kievan Rus' as part of national history has also been a topic of contention in Ukrainophile vs. Russophile schools of historiography since the Soviet era.[37] Today, he is regarded as a symbol in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

All branches of the economy prospered under him.[38] He minted coins and regulated foreign affairs with other countries, such as trade, bringing in Greek wines, Baghdad spices, and Arabian horses for the markets of Kiev.

Vladimir the Great on the Millennium of Russia monument in Novgorod

Vladimir the Great on the Millennium of Russia monument in Novgorod Monument to Vladimir the Great and the monk Fyodor at Pushkin Park in Vladimir, Russia

Monument to Vladimir the Great and the monk Fyodor at Pushkin Park in Vladimir, Russia Monument to Volodymyr the Great in Kyiv

Monument to Volodymyr the Great in Kyiv Statue in London: "St Volodymyr – Ruler of Ukraine, 980–1015, erected by Ukrainians in Great Britain in 1988 to celebrate the establishment of Christianity in Ukraine by St. Volodymir in 988"

Statue in London: "St Volodymyr – Ruler of Ukraine, 980–1015, erected by Ukrainians in Great Britain in 1988 to celebrate the establishment of Christianity in Ukraine by St. Volodymir in 988".jpg.webp) St Vladimir the Great Monument in Belgorod, Russia

St Vladimir the Great Monument in Belgorod, Russia

See also

- Order of Saint Vladimir

- List of Russian rulers

- List of Ukrainian rulers

- Family life and children of Vladimir I

- List of people known as The Great

- Saint Vladimir Monument in Kyiv (1853)

- Monument to Vladimir the Great (Moscow) in 2016

- Prince Vladimir, Russian animated feature film (2006)

- Viking, Russian historical film (2016)

Notes

- Volodiměrъ is the East Slavic form of the given name; this form was influenced and partially replaced by the Old Bulgarian (Old Church Slavonic) form Vladiměrъ (by folk etymology later also Vladimirъ; in modern East Slavic, the given name is rendered Belarusian: Уладзiмiр, Uladzimir, Russian: Владимир, Vladimir, Ukrainian: Володимир, Volodymyr. See Vladimir (name) for details.

- Russian: Владимир Святославич, Vladimir Svyatoslavich; Ukrainian: Володимир Святославич, Volodymyr Sviatoslavych; Old Norse Valdamarr gamli;[7]

- In 983, after another of his military successes, Prince Vladimir and his army thought it necessary to sacrifice human lives to the gods. A lot was cast and it fell on a youth, Ioann by name, the son of a Christian, Fyodor. His father stood firmly against his son being sacrificed to the idols. Further, he tried to show the pagans the futility of their faith: "Your gods are just plain wood: it is here now but it may rot into oblivion tomorrow; your gods neither eat, nor drink, nor talk and are made by human hand from wood; whereas there is only one God — He is worshiped by Greeks and He created heaven and earth; and your gods? They have created nothing, for they have been created themselves; never will I give my son to the devils!"

References

- Kevin Alan Brook (2006). The Jews of Khazaria (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-442203-02-0.

- Александров А. А. Ольгинская топонимика, выбутские сопки и руссы в Псковской земле // Памятники средневековой культуры. Открытия и версии. СПб., 1994. С. 22—31.

- Dyba, Yury (2012). Aleksandrovych V.; Voitovych, Leontii; et al. (eds.). Історично-геогра фічний контекст літописного повідомлення про народження князя Володимира Святославовича: локалізація будятиного села [Historical-geographic figurative context of the chronicled report about the birth of Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich: localisation of a busy village] (PDF). Княжа доба: історія і культура [Era of the Princes: history and culture] (in Ukrainian). Lviv. 6. ISSN 2221-6294. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Harvard Ukrainian studies, Vol. 12–13, p. 190, Harvard Ukrainian studies, 1990

- "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Час побудови собору". 26 May 2020.

- Fagrskinna ch. 21 (ed. Finnur Jónsson 1902–8, p. 108).

- "Volodymyr the Great". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Companion to the Calendar: A Guide to the Saints and Mysteries of the Christian Calendar, p. 105, Mary Ellen Hynes, Ed. Peter Mazar, LiturgyTrainingPublications, 1993

- National geographic, Vol. 167, p. 290, National Geographic Society, 1985

- Vladimir I (Grand Prince of Kiev) at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Den hellige Vladimir av Kiev (~956–1015), Den katolske kirke website

- Vladimir the Great, Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Saint Vladimir the Baptizer: Wetting cultural appetites for the Gospel, Dr. Alexander Roman, Ukrainian Orthodoxy website

- Ukrainian Catholic Church: part 1., The Free Library

- Bain 1911.

- Levin, Eve (1 January 1995). Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs 900–1700. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501727627. ISBN 978-1-5017-2762-7.

- Den hellige Vladimir av Kiev (~956–1015), Den Katolske Kirke

- Janet Martin. Medieval Russia. Cambridge University Press. 1995. pp. 5, 15, 20.

- John Channon, Robert Hudson. The Penguin historical atlas of Russia. Viking. 1995. p. 23.

- "Although Christianity in Kiev existed before Vladimir's time, he had remained a pagan, accumulated about seven wives, established temples, and, it is said, taken part in idolatrous rites involving human sacrifice." (Britannica online)

- Janet, Martin (2007). Medieval Russia, 980-1584 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780511811074. OCLC 761647272.

- Readings in Russian Civilization, Volume 1: Russia Before Peter..., University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Moss 2002, p. 18.

- The Earliest Mediaeval Churches of Kiev, Samuel H. Cross, H. V. Morgilevski and K. J. Conant, Speculum, Vol. 11, No. 4 (Oct., 1936), 479.

- The Earliest Mediaeval Churches of Kiev, Samuel H. Cross, H. V. Morgilevski and K. J. Conant, Speculum, 481.

- Ibn al-Athir dates these events to 985 or 986 in his The Complete History

- "Rus". Encyclopaedia of Islam

- Curta, Florin (12 December 2007). The Other Europe in the Middle Ages. Brill. ISBN 9789047423560. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Obolensky, Alexander (1993). "From First to Third Millennium: The Social Christianity of St. Vladimir of Kiev". Cross Currents.

- Ware, Timothy (29 April 1993). The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192500-4.

- Pchelov, E.V. (2002). Rurikovichi: Istoriya dinastii (Online edition (No longer available) ed.). Moscow.

- "St. Vladimir". Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- День Св. Володимира Великого, християнського правителя (in Ukrainian). Ukrainian Lutheran Church. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Henryk Paszkiewicz. The making of the Russian nation. Greenwood Press. 1977. Cracow 1996, pp. 77–79.

- С. В. Шевченко (ред.). К вопросу о дате основания г. Владимира, ТОО "Местное время", 1992. (S. V. Shevchenko (ed.). On the foundation date of Vladimir. in Russian)

- A tale of two Vladimirs, The Economist (5 November 2015)

From one Vladimir to another: Putin unveils huge statue in Moscow, The Guardian (5 November 2015)

Putin unveils 'provocative' Moscow statue of St Vladimir, BBC News (5 November 2016) - Volkoff, Vladimir (2011). Vladimir the Russian Viking. New York: Overlook Press.

- Golden, P. B. (2006) "Rus." Encyclopaedia of Islam (Brill Online). Eds.: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Vladimir, St". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 168.

- Some historical analysis and political insights on the state affairs of Vladimir the Great (in Russian)

- Moss, Walter (2002). A history of Russia. London: Anthem. ISBN 978-1-84331-023-5. OCLC 53250380.

External links

- Velychenko, Stephen, How Valdamarr Sveinaldsson got to Moscow (krytyka.com), 9 November 2015.