Figure skating jumps

Figure skating jumps are an element of three competitive figure skating disciplines—men's singles, women's singles, and pair skating, but not ice dancing.[lower-alpha 1] Jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent".[2] They were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures; many jumps were named after the skaters who invented them or from the figures from which they were developed. It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, when jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented and when jumps were formally categorized. In the 1920s, Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice. Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed. Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s. During the post-war period and into the 1950s and early 1960s, triple jumps became more common for both male and female skaters, and a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps had been fully developed. In the 1980s, men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples. By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.

| ISU abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| 1Eu | Euler jump |

| T | Toe loop |

| F | Flip |

| Lz | Lutz |

| S | Salchow |

| Lo | Loop |

| A | Axel |

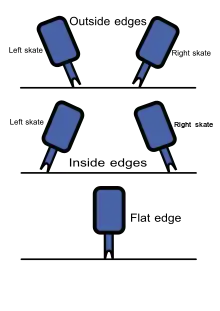

The six most common jumps can be divided into two groups: toe jumps (the toe loop, the flip, and the Lutz) and edge jumps (the Salchow, the loop, and the Axel). The Euler jump, which was known as a half loop before 2018, is an edge jump. Jumps are also classified by the number of revolutions. Pair skaters perform two types of jumps: side-by-side jumps, in which jumps are accomplished side by side and in unison, and throw jumps, in which the woman performs the jump when assisted and propelled by her partner.

According to the International Skating Union (ISU), jumps must have the following characteristics to earn the most points: they must have "very good height and very good length";[3] they must be executed effortlessly, including the rhythm demonstrated during jump combinations; and they must have good take-offs and landings. The following are not required, but also taken into consideration: there must be steps executed before the beginning of the jump, or it must have either a creative or unexpected entry; the jump must match the music; and the skater must have, from the jump's take-off to its landing, a "very good body position".[3] A jump combination, defined as "two (or more) jumps performed in immediate succession",[4] is executed when a skater's landing foot of the first jump is also the take-off foot of the following jump.[4][5] All jumps are considered in the order that they are completed. Pair teams, both juniors and seniors, must perform one solo jump during their short programs.

Jumps are divided into eight parts: the set-up, load, transition, pivot, takeoff, flight, landing, and exit. All jumps except the Axel are taken off while skating backward; Axels are entered into by skating forward. A skater's body absorbs up to 13–14 g-forces each time he or she lands from a jump, which may contribute to overuse injuries and stress fractures. Skaters add variations or unusual entries and exits to jumps to increase difficulty. Factors such as angular momentum, the moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and the skater's center of mass determines if a jump is successfully completed.

History

According to figure skating historian James R. Hines, jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent".[2] Jumps were viewed as "acrobatic tricks, not as a part of a skater’s art"[6] and "had no place"[7] in the skating practices in England during the 19th century, although skaters experimented with jumps from the ice during the last 25 years of the 1800s. Hops, or jumps without rotations, were done for safety reasons, to avoid obstacles, such as hats, barrels, and tree logs, on natural ice.[8][9] In 1881, Spuren Auf Dem Eise ("Tracing on the Ice"), "a monumental publication describing the state of skating in Vienna",[10] briefly mentioned jumps, describing three jumps in two pages.[11] Jumping on skates was a part of the athletic side of free skating, and was considered inappropriate for female skaters.[12]

Hines states that free skating movements such as spirals, spread eagles, spins, and jumps were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures. For example, Norwegian skater Axel Paulsen, whom Hines calls "progressive",[13] performed the first jump in competition, the Axel, which was named after him, at the first international competition in 1882, as a special figure.[14] Jumps were also related to their corresponding figure; for example, the loop jump. Other jumps, such as the Axel and the Salchow, were named after the skaters who invented them.[6] It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, when jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented and when jumps were formally categorized. These jumps became elements in athletic free skating programs, but they were not worth more points than no-revolution jumps and half jumps. In the 1920s, Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice and refine rotations in the Axel.[9] Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed.[15]

Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s.[2][9] Athleticism in the sport increased between the world wars, especially by women like Norwegian world and Olympic champion Sonia Henie, who popularized short skirts that allowed female skaters to maneuver and perform jumps. When international competitions were interrupted by World War II, double jumps by both men and women had become commonplace, and all jumps, except for the Axel, were being doubled.[16][17] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum, "the development of rotational technique required for Axels and double jumps continued",[18] especially in the United States and Czechoslovakia. Post-war skaters, according to Hines, "pushed the envelope of jumping to extremes that skaters of the 1930s would not have thought possible".[19] For example, world champion Felix Kasper from Austria was well known for his athletic jumps, which were the longest and highest in the history of figure skating. Hines reported that his Axel measured four feet high and 25 feet from takeoff to landing. Both men and women, including women skaters from Great Britain, were doubling Salchows and loops in their competition programs.[20]

During the post-war period, American skater Dick Button, who "intentionally tried to bring a greater athleticism to men’s skating",[18] performed the first double Axel in competition in 1948 and the first triple jump, a triple loop, in 1952.[18] Triple jumps, especially triple Salchows, became more common for male skaters during the 1950s and early 1960s, and female skaters, especially in North America, included a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, men commonly performed triple Salchows and women regularly performed double Axels in competitions. Men would also include more difficult multi-revolution jumps like triple flips, Lutzes, and loops; women included triple Salchows and toe loops. In the 1980s, men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples such as the loop jump.[21] By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.[22] According to Kestnbaum, jumps like the triple Lutz became more important during women's skating competitions.[23] The last time a woman won a gold medal at the Olympics without a triple jump was Dorothy Hamill at the 1976 Olympics.[24] According to sports reporter Dvora Meyers, the "quad revolution in women’s figure skating"[24] of the early 21st century began in 2018, when Russian skater Alexandra Trusova began performing a quadruple Salchow when she was still competing as a junior.

Types of jumps

- Anomalies in the take-off and landing highlighted in bold and italic

- All basic figure skating jumps are landed backwards.

| Abbr. | Jump | Toe assist |

Change of foot |

Change of edge |

Change of curve |

Change of direction |

Take-off edge | Landing edge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Axel | — | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | Forward outside | Outside (opposite foot) |

| Lz | Lutz | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | — | Backward outside | Outside (opposite foot) |

| F | Flip | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward inside | Outside (opposite foot) |

| Lo | Loop | — | — | — | — | — | Backward outside | Outside (same foot) |

| S | Salchow | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward inside | Outside (opposite foot) |

| T | Toe loop | ✓ | — | — | — | — | Backward outside | Outside (same foot) |

| Eu | Euler (half-loop) |

— | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | Backward outside | Inside (opposite foot) |

The six most common jumps can be divided into two groups: toe jumps (the toe loop, the flip, and the Lutz) and edge jumps (the Salchow, the loop, and the Axel).[25] The Euler jump, which was known as a half loop before 2018, is an edge jump.[26] Toe jumps tend to be higher than edge jumps because skaters press the toe pick of their skate into the ice on takeoff.[13] Both feet are on the ice at the time of take-off, and the toe-pick in the ice at take-off acts as a pole vault. It is impossible to add a half-revolution to toe jumps.[27]

Skaters accomplish edge jumps by leaving the ice from any of their skates' four possible edges; lift is "achieved from the spring gained by straightening of a bent knee in combination with a swing of the free leg".[13] They require precise rotational control of the skater's upper body, arms, and free leg, and of how well he or she leans into the take-off edge. The preparation going into the jump and its take-off, as well as controlling the rotation of the preparation and take-off, must be precisely timed.[28] When a skater executes an edge jump, they must extend their leg and use their arms more than when they execute toe jumps.[29]

Jumps are also classified by the number of revolutions. For example, all single jumps, except for the Axel, include one revolution, double jumps include two revolution, and so on. More revolutions earn skaters earn more points.[13] Double and triple versions have increased in importance "as a measure of technical and athletic ability, with attention paid to clean takeoffs and landings".[30] Pair skaters perform two types of jumps: side-by-side jumps, in which jumps are accomplished side by side and in unison, and throw jumps, in which the woman performs the jump when assisted and propelled by her partner.[13]

Euler jump

The Euler is an edge jump. It was known as the half loop jump in International Skating Union (ISU) regulations prior to the 2018–2019 season, when the name was changed.[26] In Europe, the Euler is also called the Thorén jump, after its inventor, Swedish figure skater Per Thorén.[31] The Euler is executed when a skater takes off from the back outside edge of one skate and lands on the opposite foot and edge. It is most commonly done prior to the third jump during a three-jump combination, and serves as a way to put a skater on the correct edge in order to attempt a Salchow jump or a flip jump. It can only be accomplished as a single jump.[26] The Euler has a base point value of 0.50 points, when used in combination between two listed jumps, and also becomes a listed jump.[32]

Toe loop jump

The toe loop jump is the simplest jump in figure skating.[33] It was invented in the 1920s by American professional figure skater Bruce Mapes.[34] In competitions, the base value of a single toe loop is 0.40; the base value of a double toe loop is 1.30; the base value of a triple toe loop is 4.20; and the base value of a quadruple toe loop is 9.50.[32]

The toe loop is considered the simplest jump because not only do skaters use their toe-picks to execute it, their hips are already facing the direction in which they will rotate.[35] The toe loop is the easier jump to add multiple rotations to because the toe-assisted takeoff adds power to the jump and because a skater can turn his or her body towards the assisting foot at takeoff, which slightly reduces the rotation needed in the air.[36] It is often added to more difficult jumps during combinations, and is the most common second jump performed in combinations.[37] It is also the most commonly attempted jump,[35] as well as "the most commonly cheated on take off jump",[38] or a jump in which the first rotation starts on the ice rather than in the air.[36] Adding a toe loop to combination jumps does not increase the difficulty of skaters' short or free skating programs.[39]

Flip jump

The ISU defines a flip jump as "a toe jump that takes off from a back inside edge and lands on the back outside edge of the opposite foot".[34] It is executed with assistance from the toe of the free foot.[40] In competitions, the base value of a single flip is 0.50; the base value of a double flip is 1.80; the base value of a triple flip is 5.50; and the base value of a quadruple flip is 11.00.[32]

Lutz jump

The ISU defines the Lutz jump as "a toe-pick assisted jump with an entrance from a back outside edge and landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot".[34] It is the second-most difficult jump in figure skating[33] and "probably the second-most famous jump after the Axel".[37] It is named after figure skater Alois Lutz from Vienna, Austria, who first performed it in 1913.[34][37] In competitions, the base value of a single Lutz is 0.60; the base value of a double Lutz is 2.10; the base value of a triple Lutz is 5.90; and the base value of a quadruple Lutz is 11.50.[32] A "cheated" Lutz jump without an outside edge is called a "flutz".[37]

Salchow jump

The Salchow jump is an edge jump. It was named after its inventor, Ulrich Salchow, in 1909.[34][41] The Salchow is accomplished with a takeoff from the back inside edge of one foot and a landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot.[34] It is "usually the first jump that skaters learn to double, and the first or second to triple".[42] Timing is critical because both the takeoff and landing must be on the backward edge.[37] A Salchow is deemed cheated if the skate blade starts to turn forward before the takeoff, or if it has not turned completely backward when the skater lands back on the ice.[42]

In competitions, the base value of a single Salchow is 0.40; the base value of a double Salchow is 1.30; the base value of a triple Salchow is 4.30; and the base value of a quadruple Salchow is 9.70.[32]

Loop jump

The loop jump is an edge jump. It was believed to be created by German figure skater Werner Rittberger, and is known as the Rittberger in Russian and German.[34][43] It also gets its name from the shape the blade would leave on the ice if the skater performed the rotation without leaving the ice.[44] According to U.S. Figure Skating, the loop jump is "the most fundamental of all the jumps".[37] The skater executes it by taking off from the back outside edge of the skating foot, turning one rotation in the air, and landing on the back outside edge of the same foot.[40] It is often performed as the second jump in a combination.[45]

In competitions, the base value of the single loop jump is 0.50; the base value of a double loop is 1.70; the base value of a triple loop is 4.90; and the base value of a quadruple loop is 10.50.[32]

Axel jump

The Axel jump, also called the Axel Paulsen jump for its creator, Norwegian figure skater Axel Paulsen, is an edge jump.[46] It is figure skating's oldest and most difficult jump.[17][44] The Axel jump is the most studied jump in figure skating.[47] It is the only jump that begins with a forward takeoff, which makes it the easiest jump to identify.[25] A double or triple Axel is required in both the short programs and free skating programs for junior and senior single skaters in all ISU competitions.[48]

The Axel has an extra half rotation, which, as figure skating expert Hannah Robbins states, makes a triple Axel "more a quadruple jump than a triple".[49] Sports reporter Nora Princiotti states, about the triple Axel, "It takes incredible strength and body control for a skater to get enough height and to get into the jump fast enough to complete all the rotations before landing with a strong enough base to absorb the force generated".[50] According to American skater Mirai Nagasu, "falling on the triple Axel is really brutal".[51]

In competitions, the base value of a single Axel is 1.10; the base value of a double Axel is 3.30; the base value of a triple Axel is 8.00; and the base value of a quadruple Axel is 12.50.[32] According to The New York Times, the triple Axel has become more common for male skaters to perform;[52] however, the quadruple Axel has only been landed at an international competition by Ilia Malinin as of 2022.

Rules and regulations

Single skating

The International Skating Union defines a jump element for both single skating and pair skating disciplines as "an individual jump, a jump combination or a jump sequence".[5] Jumps are not allowed in ice dance.[53]

Also according to the ISU, jumps must have the following characteristics to earn the most points: they must have "very good height and very good length";[3] they must be executed effortlessly, including the rhythm demonstrated during jump combinations; and they must have good take-offs and landings. The following are not required, but also taken into consideration: there must be steps executed before the beginning of the jump, or it must have either a creative or unexpected entry; the jump must match the music; and the skater must have, from the jump's take-off to its landing, a "very good body position".[3] Somersault-type jumps, like the back flip, are not allowed. The back flip has been banned by the ISU since 1976 because it was deemed too dangerous and lacked "aesthetic value".[54][55]

A jump sequence consists of "two or three jumps of any number of revolutions"[56] and is executed when a skater's landing foot of the first jump is also the take-off foot of the following jump.[5][4] The free foot can touch the ice, but there must be no weight transfer on it and if the skater makes one full revolution between the jumps, the element continues to be deemed a jump sequence and receive their full value.[56] The second and/or third jump must be an Axel-type jump, "with a direct step from the landing curve of the first/second jump in to the takeoff curve of the Axel jump".[56] The skater can also perform an Euler between jumps.[5][lower-alpha 2]

.jpg.webp)

All jumps are considered in the order that they are completed. If an extra jump or jumps are completed, only the first jump will be counted; jumps done later in the program will have no value.[58] The limitation on the number of jumps skaters can perform in their programs, called the "Zayak Rule" after American skater Elaine Zayak, has been in effect since 1983, after Zayak performed six triple jumps, four toe loop jumps, and two Salchows in her free skating program at the 1982 World Championships.[59][22] Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum states that the ISU established the rule "in order to encourage variety and balance rather than allowing a skater to rack up credit for demonstrating the same skill over and over".[22] Kestnbaum also states that as rotations in jumps for both men and women have increased, skaters have increased the difficulty of jumps by adding more difficult combinations and by adding difficult steps immediately before or after their jumps, resulting in "integrating the jumps more seamlessly into the flow of the program".[60]

In both the short program and free skating, any jump, jump combination, or jump sequence begun during the second half of the program earns extra points "in order to give credit for even distribution of difficulties in the program".[61] As of the 2018–2019 season, however, only the last jump element performed during the short program and the final three jump elements performed during the free skate, counted in a skater's final score. International Figure Skating magazine called this regulation the "Zagitova Rule", named for Alina Zagitova from Russia, who won the gold medal at the 2018 Winter Olympics by "backloading" her free skating program, or placing all her jumps in the second half of the program in order to take advantage of the rule in place at the time that awarded a 10% bonus to jumps performed during the second half of the program.[57][62] Also starting in 2018, single skaters could only repeat the same two triple or quadruple jumps in their free skating programs. They could repeat four-revolutions jumps only once, and the base value of the triple Axel and quadruple jumps were "reduced dramatically".[57] Junior men and women single skaters are not allowed to perform quadruple jumps in their short programs.[63] Both junior and senior skaters receive no points for jumps performed during their short programs that do not satisfy the requirements, including completing the wrong number of revolutions.[64]

Pair skating

Pair teams, both juniors and seniors, must perform one solo jump during their short programs; it can include a double flip or double Axel for juniors, or any kind of double or triple jump for seniors.[65] In the free skating program, for both juniors and seniors, skaters can perform up to three jump combinations or two jump combinations and one jump sequence; a jump combination and jump sequence can consist of the same or another single, double, triple, or quadruple jump. One jump combination or jump sequence can consist of up to three jumps, while the other two can consist of up to two jumps each.[66] A jump sequence starts with any type of jump, immediately followed by an Axel-type jump.[65] Junior pairs, during their short programs, earn no points for the solo jump if they perform a different jump than what is required. Both junior and senior pairs earn no points if, during their free skating programs, they repeat a jump with over two revolutions.[67]

All jumps are considered in the order in which they were performed. If the partners do not execute the same number of revolutions during a solo jump or part of a jump sequence or combination (which can consist of two or three jumps), only the jump with the fewer revolutions will be counted in their score.[68] The double Axel and all triple and quadruple jumps, which have more than two revolutions, must be different from one another, although jump sequences and combinations can include the same two jumps. Extra jumps that do not fulfill the requirements are not counted in the team's score.[69] Teams are allowed, however, to execute the same two jumps during a jump combination or sequence. If they perform any or both jump or jumps incorrectly, only the incorrectly-done jump is not counted and it is not considered a jump sequence or combination. Both partners can execute two solo jumps during their short programs, but the second jump is worth less points than the first.[67]

Throw jumps are "partner assisted jumps in which the Woman is thrown into the air by the Man on the take-off and lands without assistance from her partner on a backward outside edge".[70] Skate Canada says, "the male partner assists the female into flight".[40] The types of throw jumps include: the throw Axel, the throw Salchow, the throw toe loop, the throw loop, the throw flip, and the throw Lutz.[40] The throw triple Axel is a difficult throw to accomplish because the woman must perform three-and-one-half revolutions after being thrown by the man, a half-revolution more than other triple jumps, and because it requires a forward take-off.[71] The speed of the team's entry into the throw jump and the number of rotations performed increases its difficulty, as well as the height and/or distance they create.[40] Pair teams must perform one throw jump during their short programs; senior teams can perform any double or triple throw jump, and junior teams must perform a double or triple toe loop, flip, or Lutz. If the throw jump is not done correctly, including if it has the wrong number of revolutions, it receives no value. Pair teams must perform at least two different throw jumps with a different number of revolutions in their free skating programs. A throw jump is judged as a jump with a higher number of revolution if it is over-rotated more than a quarter revolution; for example, if a pair attempts a double throw jump but over-rotates it, the judges record it as a downgraded triple throw jump.[72]

Execution

According to Kestbaum, jumps are divided into eight parts: the set-up, load, transition, pivot, takeoff, flight, landing, and exit. All jumps, except for the Axel, are taken off while skating backward; Axels are entered into by skating forward.[73] Skaters travel in three directions simultaneously while executing a jump: vertically (up off the ice and back down); horizontally (continuing along the direction of travel before leaving the ice); and around.[30][74] They travel in an up and across, arc-like path while executing a jump, much like the projectile motion of a pole-vaulter. A jump's height is determined by vertical velocity and its length is determined by vertical and horizontal velocity.[75] The trajectory of the jump is established during takeoff, so the shape of the arc cannot be changed once a skater is in the air.[76] Their body absorbs up to 13—14 g-forces each time they land from a jump,[77] which sports researchers Lee Cabell and Erica Bateman state contributes to overuse injuries and stress fractures.[78]

Skaters add variations or unusual entries and exits to jumps to increase difficulty. For example, they will perform a jump with one or both arms overhead or extended at the hips, which demonstrates that they are able to generate rotation from the takeoff edge and from their entire body instead of relying on their arms. It also demonstrates their back strength and technical ability to complete the rotation without relying on their arms. Unusual entries into jumps demonstrate that skaters are able to control both the jump and with little preparation, the transition from the previous move to the jump.[73] Skaters rotate more quickly when their arms are pulled in tightly to their bodies, which requires strength to keep their arms being pulled away from their bodies as they rotate.[79]

According to scientist Deborah King from Ithaca College, there are basic physics common to all jumps, regardless of the skating techniques required to execute them.[29] Factors such as angular momentum, the moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and the skater's center of mass determines if a jump is successfully completed.[80][81] Unlike jumping from dry land, which is fundamentally a linear movement, jumping on the ice is more complicated because of angular momentum. For example, most jumps involve rotation.[82] Scientist James Richards from the University of Delaware stated that successful jumps depend upon "how much angular momentum do you leave the ice with, how small can you make your moment of inertia in the air, and how much time you can spend in the air".[80] Richards found that a skater tends to spend the same amount of time in the air when performing triple and quadruple jumps, but their angular momentum at the start of triples and quadruples is slightly higher than it is for double jumps. The key to completing higher-rotation jumps is how they control the moment of inertia. Richards also found that many skaters, although they were able to gain the necessary angular momentum for takeoff, had difficulty gaining enough rotational speed to complete the jump.[80] King agrees, stating that skaters must be in the air long enough, have enough jump height to complete the required revolutions, and the amount of vertical velocity they are able to gain as they jump off the ice, although different jumps require different patterns of movement. Skaters performing quadruple jumps tend to be in the air longer and have more rotational speed. King also found that most skaters "actually tended to skate slower into their quads as compared to their triples",[83] although the differences in the speed in which they approached triples and quadruples were small. King conjectured that slowing their approach into the jumps were due to skaters' "confidence and a feeling of control and timing for the jump",[83] rather than any difference in how they executed them. Vertical take-off velocity, however, was higher for both quadruple and triple toe loops, resulting in "higher jumps and more time in the air to complete the extra revolution for the quadruple toe-loop".[83] As Tanya Lewis of Scientific American puts it, executing quadruple jumps, which as of 2022, has become more common in both male and female single skating competitions, requires "exquisite strength, speed and grace".[29]

For example, a skater could successfully complete a jump by making small changes to their arm position partway through the rotation, and a small bend in the hips and knees allows a skater "to land with a lower center of mass than they started with, perhaps seeking out a few precious degrees of rotation and a better body position for landing".[80] When they execute a toe jump, they must use their skate's toe pick to complete a pole-vaulting-type motion off the ice, which along with extra horizontal speed, helps them store more energy in their leg. As they rotate over their leg, their horizontal motion converts into tangential velocity.[29] King, who believes that quintuple jumps are mathematically possible, states that in order to execute more rotations, they could improve their rotational momentum as they execute their footwork or approach into their takeoff, creating torque about the rotating axis as they come off the ice. She also states that if skaters can increase their rotational momentum while "still exploding upward",[29] they can rotate faster and increase the number of revolutions they perform. Sports writer Dvora Meyers, reporting on Russian coaching techniques, states that the female skaters executing more quadruple jumps in competition use what experts call pre-rotation, or the practice of twisting their upper bodies before they take off from the ice, which allows them to complete four revolutions before landing. Meyers also states that the technique depends on the skater being small, light, and young, and that it puts more strain on the back because they do not use as much leg strength. As a skater ages and goes through puberty, however, they tend to not be able to execute quadruple jumps because "the technique wasn’t sound to start with".[24] They also tend to retire before the age of 18 due to the increase of back injuries.[24]

Since the tendency of an edge is toward the center of the circle created by that edge, a skater's upper body, arms, and free leg also have a tendency to be pulled along by the force of the edge. If the upper body, arms, and free leg are allowed to follow passively, they will eventually overtake the edge's rotational edge and will rotate faster, a principle that is also used to create faster spins. The inherent force of the edge and the force generated by a skater's upper body, arms, and free leg tend to increase rotation, so successful jumping requires precise control of these forces. Leaning into the curvature of the edge is how skaters regulate the edge's inherent angular momentum. Their upper body, arms, and free leg are controlled by what happens at the time of preparation for the jump and its take-off, which are designed to produce the correct amount of rotation on the take-off. If they do not have enough rotation, they will not be at the correct position at the take-off; if they rotate too much, their upper body will not be high enough in the air. Skaters must keep track of the many different movements and body positions, as well as the timing of those movements relative to each other and to the jump itself, which requires hours of practice but once mastered, becomes natural.[84]

The number of possible combinations jumps are limitless; if a turn or change of feet is permitted between combination jumps, any number of sequences is possible, although if the landing of one jump is the take-off of the next, as is the case in loop combinations, how the skater lands will dictate the possibilities going into subsequent jumps. Rotational momentum tends to increase during combination jumps, so skaters should control rotation at the landing of each jump; if a skater does not control rotation, they will overrotate on subsequent jumps and probably fall. The way that skaters control rotation differs depending upon the nature of the landing and take-off edges, and the way they use their arms, which regulate their shoulders and upper body position, and free leg, which dictates the positioning of their hips. If the landing on one jump leads directly into the take-off of the jump that follows it, the bend on the landing leg of the first jump serves as preparation for the spring of the take-off of the subsequent jump. If some time elapses between the completion of the first jump and the take-off of the subsequent one, or if a series of movements serve as preparation for the subsequent jump, the leg bend for the spring can be separated from the bend of the landing leg.[85]

History of first jumps

The following table lists first recorded jumps in competition for which there is secure information.

| Jump | Abbr. | Men | Year | Ladies | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single toe loop | 1T | 1920s | n/a | [34] | ||

| Single Salchow | 1S | 1909 | 1920 | [34][16] | ||

| Single loop | 1Lo | n/a | [34] | |||

| Single Lutz | 1Lz | 1913 | n/a | [34] | ||

| Single Axel | 1A | 1882 | 1920s | [34][46] | ||

| Double Salchow | 2S | n/a | 1920s | 1930s | [86] | |

| Double Lutz | 2Lz | n/a | 1949 | [87] | ||

| Double Axel | 2A | 1948 | 1953 | [34][88] | ||

| Triple toe loop | 3T | 1964 | n/a | [89] | ||

| Triple Salchow | 3S | 1955 | 1962 | [89] | ||

| Triple loop | 3Lo | 1952 | 1968 | [90][89] | ||

| Triple flip | 3F | n/a | 1981 | [34] | ||

| Triple Lutz | 3Lz | 1962 | 1978 | [34] | ||

| Triple Axel | 3A | 1978 | 1988 | [34] | ||

| Quadruple toe loop | 4T | 1988 | 2018 | [91][89] | ||

| Quadruple Salchow | 4S | 1998 | 2002 | [89] | ||

| Quadruple loop | 4Lo | 2016 | 2022 | [89][92] | ||

| Quadruple flip | 4F | 2016 | 2019 | [93][94] | ||

| Quadruple Lutz | 4Lz | 2011 | 2018 | [35][95] | ||

| Quadruple Axel | 4A | 2022 | none ratified | [96] | ||

- ★ Outside of competition.

- ★ ★ Domestic competition.

Footnotes

References

- "Results of Proposals in replacement of the 58th Ordinary ISU Congress 2021" (Press release). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Hines 2011, p. 131.

- ISU No. 2168, p. 13

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 289.

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 100

- Hines 2006, p. 101.

- Hines 131, p. 2006.

- Hines 2011, p. 131—132.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 91.

- Hines 2011, p. 66.

- Hines 2011, p. 68.

- Kestnbaum 2003, pp. 91–92.

- Hines 2011, p. 132.

- Hines 2006, p. 100.

- Hines 2006, p. 5.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 92.

- Hines 2011, p. xxxii.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 93.

- Hines 2006, p. 102.

- Hines 2006, p. 103.

- Kestnbaum 2003, pp. 93–95.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 96.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 138.

- Meyers, Dvora (3 February 2022). "How Quad Jumps Have Changed Women's Figure Skating". FiveThirtyEight. ABC News. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- Abad-Santos, Alexander (5 February 2014). "A GIF Guide to Figure Skaters' Jumps at the Olympics". The Atlantic. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Cornetta, Katherine (1 October 2018). "Breaking Down an Euler". Fanzone.com. U.S. Figure Skating. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Petkevich 1988, p. 237.

- Petkevich 1988, p. 199.

- Lewis, Tanya (14 February 2022). "How Olympic Figure Skaters Break Records with Physics". Scientific American. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 282.

- Hines 2011, p. 222.

- ISU No. 2168, p. 2

- Park, Alice (22 February 2018). "How to Tell the Difference Between the 6 Figure Skating Jumps You'll See at the Olympics". Time. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Media Guide, p. 16

- Sarkar, Pritha; Fallon, Clare (28 March 2017). "Figure Skating - Breakdown of Quadruple Lumps, Highest Scores and Judging". Reuters. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 287.

- USFS, p. 2

- "ISU Judging System: Technical Panel Handbook: Pair Skating 2021/2022"". International Skating Union. 8 July 2021. p. 16. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- King, Deborah; Smith, Sarah; Higginson, Brian; Muncasy, Barry; Scheirman, Gary (2004). "Characteristics of Triple and Quadruple Toe-Loops Performed during The Salt Lake City 2002 Winter Olympics". Sports Biomechanics. 3 (1): 112. doi:10.1080/14763140408522833. PMID 15079991. S2CID 14116488.

- "Skating Glossary". Skate Canada. 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Hines 2011, p. 193.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 284.

- Hines 2011, p. 150.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 285.

- Kestnbaum, p. 285

- USFS, p. 1

- Mazurkiewicz, Anna; Twańsak, Dagmara; Urbanik, Czesław (July 2018). "Biomechanics of the Axel Paulsen Figure Skating Jump". Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism. 25 (2): 3. doi:10.2478/pjst-2018-0007.

- S&P/ID 2018, pp. 102–104, 106–107

- Robbins, Hannah (11 February 2018). "Triple Axel New Ladies' Figure Skating Staple". The Collegian. Tulsa, Oklahoma: University of Tulsa. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Princiotti, Nora (12 February 2018). "What is a Triple Axel? And Why is it So Hard for Figure Skaters to Pull Off?". Boston.com. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Calfas, Jennifer (12 February 2018). "Why Mirai Nagasu's Historic Triple Axel at the Olympics Is Such a Big Deal". Time. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Victor, Daniel (12 February 2018). "Mirai Nagasu Lands Triple Axel, a First by an American Woman at an Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Samuels, Robert (18 February 2018). "Ice Dancing is More than pairs Figure Skating Without Jumps". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Hines 2006, pp. 29, 91.

- Brown, Stacia L. (18 August 2015). "The Rebellious, Back-Flipping Black Figure Skater Who Changed the Sport Forever". The New Republic. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Communication No. 2494: Single & Pair Skating/Ice Dance". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2022. p. 3. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- Walker, Elvin (19 September 2018). "New Season New Rules". International Figure Skating. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- S&P/ID 2021, p. 105

- Hines 2006, p. xxvii.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 99.

- S&P/ID 2018, p. 16

- Germano, Sara (21 February 2018). "In Figure Skating, Russia's (Perfectly Legal) Secret Sauce". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Russell, Susan D. (December 2019). "Talent and Tenacity: Next Gen Makes History on the Junior Grand Prix Circuit". International Figure Skating. p. 23.

- "Communication No. 2334". International Skating Union. 8 July 2020. p. 3. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Tech Panel, p. 15

- "Communication No. 2494: Single & Pair Skating/Ice Dance". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2022. p. 4. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Tech Panel, p. 17

- S&P/ID 2018, pp. 113, 118

- S&P/ID 2021, p. 116

- S&P/ID 2021, p. 111

- Henderson, John (26 January 2006). "Duo Throws Caution to Wind". The Denver Post. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Tech Panel, p. 18

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 27.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 21.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 19.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 20.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 35.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 38.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 22.

- Lamb, Evelyn (7 February 2018). "How Physics Keeps Figure Skaters Gracefully Aloft". Smithsonian. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Cabell & Bateman, p. 27.

- Petkevich 1988, p. 193.

- King et al., p. 120

- Petkevich 1988, pp. 193–194.

- Petkevich 1988, pp. 271–272.

- Hines 2011, p. xxiv.

- Elliott, Helene (13 March 2009). "Brian Orser Heads List of World Figure Skating Hall of Fame Inductees". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Judd, Ron C. (2001). The Winter Olympics: An Insider's Guide to the Legends, the Lore, and the Games. Seattle, Wash.: The Mountaineer Books. p. 100.

- Media Guide, p. 17

- Pucin, Diane (7 January 2002). "Button Has Never Been Known to Zip His Lip". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "A Quadruple Jump on Ice". The New York Times. Associated Press. 26 March 1988. p. 1001057. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Hanyu First to Nail Quadruple Loop". The Japan Times. Kyodo News. 1 October 2016. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Media Guide, p. 18

- Griffiths, Rachel; Jiwani, Rory (6 December 2019). "As it Happened: Wins for Kostornaia and Chen on Last Day of Competition in Turin". Olympic Channel. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Media Guide, p. 18

- "Ilia Malinin (USA) lands first quad Axel - International Skating Union". isu.org. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

Works cited

- Cabell, Lee; Bateman, Erica (2018). "Biomechanics in Figure Skating". In Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (eds.). The Science of Figure Skating. New York: Routledge. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0.

- "Communication No. 2168: Single & Pair Skating". (ISU No. 2168) Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 23 May 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07286-4.

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81087-0857.

- "Identifying Jumps" (PDF). (USFS) U.S. Figure Skating. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "ISU Figure Skating Media Guide 2022/23". International Skating Union. 17 October 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- King, Deborah; Smith, Sarah; Higginson, Brian; Muncasy, Barry; Scheirman, Gary (2004). "Characteristics of Triple and Quadruple Toe-Loops Performed during The Salt Lake City 2002 Winter Olympics" (PDF). Sports Biomechanics. 3 (1). Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Mazurkiewicz, Anna, Dagmara Twańsak, and Czesław Urbanik (July 2018). "Biomechanics of the Axel Paulsen Figure Skating Jump". Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism 25 (2):3-9. DOI: 10.2478/pjst-2018-0007. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Petkevich, John Misha (1988). Sports Illustrated Figure Skating: Championship Techniques (1st ed.). New York: Sports Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-4616-6440-6. OCLC 815289537.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2021". International Skating Union. June 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2022 (S&P/ID 2021).

- "ISU Judging System: Technical Panel Handbook: Pair Skating 2021/2022" (PDF). International Skating Union. 8 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2022 (Tech Panel).