Ice dance

Ice dance (sometimes referred to as ice dancing) is a discipline of figure skating that historically draws from ballroom dancing. It joined the World Figure Skating Championships in 1952, and became a Winter Olympic Games medal sport in 1976. According to the International Skating Union (ISU), the governing body of figure skating, an ice dance team consists of one woman and one man.[1]

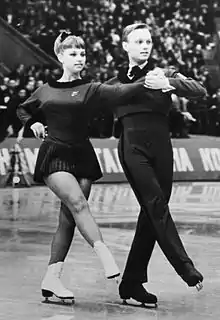

Ice dance in 1976, its first year as an official Olympic sport (Irina Moiseeva and Andrei Minenkov) | |

| Highest governing body | International Skating Union |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Team members | Duos |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Equipment | Figure skates |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Part of the Winter Olympics from 1976 |

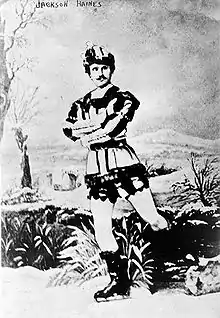

Ice dance, like pair skating, has its roots in the "combined skating" developed in the 19th century by skating clubs and organizations and in recreational social skating. Couples and friends would skate waltzes, marches, and other social dances. The first steps in ice dance were similar to those used in ballroom dancing. In the late 1800s, American Jackson Haines, known as "the Father of Figure Skating",[2] brought his style of skating, which included waltz steps and social dances, to Europe. By the end of the 19th century, waltzing competitions on the ice became popular throughout the world. By the early 1900s, ice dance was popular around the world and was primarily a recreational sport, although during the 1920s, local skating clubs in Britain and the U.S. conducted informal dance contests. Recreational skating became more popular during the 1930s in England.

The first national competitions occurred in England, Canada, the U.S., and Austria during the 1930s. The first international ice dance competition took place as a special event at the World Championships in 1950 in London. British ice dance teams dominated the sport throughout the 1950s and 1960s, then Soviet teams up until the 1990s. Ice dance was formally added to the 1952 World Figure Skating Championships; it became an Olympic sport in 1976. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was an attempt by ice dancers, their coaches, and choreographers to move ice dance away from its ballroom origins to more theatrical performances. The ISU pushed back by tightening rules and definitions of ice dance to emphasize its connection to ballroom dancing. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, ice dance lost much of its integrity as a sport after a series of judging scandals, which also affected the other figure skating disciplines. There were calls to suspend the sport for a year to deal with the dispute, which seemed to affect ice dance teams from North America the most. Teams from North America began to dominate the sport starting in the early 2000s.

Before the 2010–11 figure skating season, there were three segments in ice dance competitions: the compulsory dance (CD), the original dance (OD), and the free dance (FD). In 2010, the ISU voted to change the competition format by eliminating the CD and the OD and adding the new short dance (SD) segment to the competition schedule. In 2018, the ISU voted to rename the short dance to the rhythm dance (RD).

Ice dance has required elements that competitors must perform and that make up a well-balanced ice dance program. They include the dance lift, the dance spin, the step sequence, twizzles, and choreographic elements. These must be performed in specific ways, as described in published communications by the ISU, unless otherwise specified. Each year the ISU publishes a list specifying the points that can be deducted from performance scores for various reasons, including falls, interruptions, and violations of the rules concerning time, music, and clothing.

History

Beginnings

Ice dance, like pair skating, has its roots in the "combined skating" developed in the 19th century by skating clubs and organizations and in recreational social skating. Couples and friends would skate waltzes, marches, and other social dances together.[3] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum, ice dance began with late 19th-century attempts by the Viennese and British to create ballroom-style performances on ice skates.[4] However, figure skating historian James Hines argues that ice dance had its beginnings in hand-in-hand skating, a short-lived but popular discipline of figure skating in England in the 1890s; many of the positions used in modern ice dance can be traced back to hand-in-hand skating.[5][lower-alpha 1] The first steps in ice dance were similar to those used in ballroom dancing, so unlike modern ice dance, skaters tended to keep both feet on the ice most of the time, without the "long and flowing edges associated with graceful figure skating".[7]

In the late 1800s, American Jackson Haines, known as "the Father of Figure Skating", brought his style of skating to Europe. He taught people in Vienna how to dance on the ice, both singly and with partners. Capitalizing on the popularity of the waltz in Vienna, Haines introduced the American waltz, a simple four-step sequence, each step lasting one beat of music, repeated as the partners moved in a circular pattern.[2] By the 1880s, it and the Jackson Haines waltz, a variation of the American waltz, were among the most popular ice dances. Other popular ice dance steps included the mazurka, a version of the Jackson Haines waltz developed in Sweden, and the three-step waltz, which Hines considers "the direct predecessor of ice dancing in the modern sense".[7]

By the end of the 19th century, the three-step waltz, called the English waltz in Europe, became the standard for waltzing competitions. It was first skated in Paris in 1894; Hines states that it was responsible for the popularity of ice dance in Europe. The three-step waltz was easy and could be done by less skilled skaters, although more experienced skaters added variations to make it more difficult.[8][9] Two other steps, the killian and the ten-step, survived into the 20th century.[9][10] The ten-step, which became the fourteen-step, was first skated by Franz Schöller in 1889.[11] Also in the 1890s, combined and hand-in-hand skating moved skating away from basic figures to the continuous movement of ice dancers around an ice rink. Hines insists that the popularity of skating waltzes, which depended upon the speed and flow across the ice of couples in dance positions and not just on holding hands with a partner, ended the popularity of hand-in-hand skating.[6] Hines writes that Vienna was "the dancing capital of Europe, both on and off skates"[10] during the 19th century; by the end of the century, waltzing competitions became popular throughout the world.[8] The killian, first skated in 1909 by Austrian Karl Schreiter, was the last ice dance invented before World War I still being done as of the 21st century.[12]

Early years

By the early 1900s, ice dance was popular around the world and was primarily a recreational sport, although during the 1920s, local clubs in Britain and the U.S. conducted informal dance contests in the ten-step, the fourteen-step, and the killian, which were the only three dances used in competition until the 1930s.[4][13] Recreational skating became more popular during the 1930s in England, and new and more difficult set-pattern dances, which later were used in compulsory dances during competitions, were developed.[14] According to Hines, the development of new ice dances was necessary to expand upon the three dances already developed; three British teams in the 1930s—Erik van der Wyden and Eva Keats, Reginald Wilkie and Daphne B. Wallis, and Robert Dench and Rosemarie Stewart—created one-fourth of the dances used in International Skating Union (ISU) competitions by 2006. In 1933, the Westminster Skating Club conducted a competition encouraging the creation of new dances.[15] Beginning in the mid-1930s, national organizations began to introduce skating proficiency tests in set-pattern dances, improve the judging of dance tests, and oversee competitions. The first national competitions occurred in England in 1934, Canada in 1935, the U.S. in 1936, and Austria in 1937. These competitions included one or more compulsory dances, the original dance, and the free dance.[14][16] By the late 1930s, ice dancers swelled memberships in skating clubs throughout the world, and in Hines' words "became the backbone of skating clubs".[13]

The ISU began to develop rules, standards, and international tests for ice dance in the 1950s.[17] The first international ice dance competition occurred as a special event during the 1950 World Figure Skating Championships in London; Lois Waring and Michael McGean of the U.S. won the event, much to the embarrassment of the British, who considered themselves the best ice dancers in the world.[18] A second event was planned the following year, at the 1951 World Championships in Milan; Jean Westwood and Lawrence Demmy of Great Britain came in first place.[19] Ice dance, with the CD and FD segments, was formally added to the World Championships in 1952.[17] Westwood and Demmy won that year, and went on to dominate ice dance, winning the next four World Championships as well.[16][19] British teams won every world ice dance title through 1960.[20] Eva Romanova and Pavel Roman of Czechoslovakia were the first non-British ice dancers to win a world title, in 1962.[21]

1970s to 1990s

Ice dance became an Olympic sport in 1976; Lyudmila Pakhomova and Alexandr Gorshkov from the Soviet Union were the first gold medalists.[17][22][23] The Soviets dominated ice dance during most of the 1970s, as they did in pair skating. They won every Worlds and Olympic title between 1970 and 1978, and won medals at every competition between 1976 and 1982.[24] In 1984, British dancers Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean, who Hines calls "the greatest ice dancers in the history of the sport",[25] briefly interrupted Soviet domination of ice dance by winning a gold medal at the Olympic Games in Sarajevo. Their free dance to Ravel's Boléro[26] has been called "probably the most well known single program in the history of ice dance".[27] Hines asserts that Torvill and Dean, with their innovative choreography, dramatically altered "established concepts of ice dancing".[28]

During the 1970s, there was a movement in ice dance away from its ballroom roots to a more theatrical style. The top Soviet teams were the first to emphasize the dramatic aspects of ice dance, as well as the first to choreograph their programs around a central theme. They also incorporated elements of ballet techniques, especially "the classic ballet pas de deux of the high-art instance of a man and woman dancing together".[27] They performed as predictable characters, included body positions that were no longer rooted in traditional ballroom holds, and used music with less predictable rhythms.[27][23]

The ISU pushed back during the 1980s and 1990s by tightening rules and definitions of ice dance to emphasize its connection to ballroom dancing, especially in the free dance. The restrictions introduced during this period were designed to emphasize skating skills rather than the theatrical and dramatic aspects of ice dance.[29][30] Kestnbaum argues that there was a conflict in the ice dance community between social dance, represented by the British, the Canadians, and the Americans, and theatrical dance represented by the Russians.[31] Initially the historic and traditional cultural school of ice dance prevailed, but in 1998 the ISU reduced penalties for violations and relaxed rules on technical content, in what Hines describes as a "major step forward"[32] in recognizing the move towards more theatrical skating in ice dance.[32]

At the 1998 Olympics, while ice dance was struggling to retain its integrity and legitimacy as a sport, writer Jere Longman reported that ice dance was "mired in controversies",[33] including bloc voting by the judges that favored European dance teams. There were even calls to suspend the sport for a year to deal with the dispute, which seemed to impact ice dance teams from North America the most. A series of judging scandals in the late 1990s and early 2000s, affecting most figure skating disciplines, culminated in a controversy at the 2002 Olympics.[34][35]

21st century

The European dominance of ice dance was interrupted at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver by Canadians Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir and Americans Meryl Davis and Charlie White. The Canadian ice dance team won the first Olympic ice dance gold medal for North America, and the Americans won the silver. Russians Oksana Domnina and Maxim Shabalin won bronze, but it was the first time Europeans had not won a gold medal in the history of ice dance at the Olympics.[36]

The U.S. began to dominate international competitions in ice dance; at the 2014 Olympics in Sochi, Davis and White won the Olympic gold medal.[37] In 2018, at the Olympics in Pyeongchang, Virtue and Moir became the most decorated figure skaters in Olympic history after winning the gold medal there.[38] In 2022, Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron of France won the Olympic gold medal; they went on to win the gold medal at the World championships a few months later, ending the North American domination on ice dance. Papadakis and Cizeron broke the world record at both events.[39]

According to Caroline Silby, a consultant with U.S. Figure Skating, ice dance teams and pair skaters have the added challenge of strengthening partnerships and ensuring that teams stay together for several years; unresolved conflict between partners can often cause the early break-up of a team. Silby further asserts that the early demise or break-up of a team is often caused by consistent and unresolved conflict between partners.[40] Both ice dancers and pairs skaters face challenges that make conflict resolution and communication difficult: fewer available boys for girls to partner with; different priorities regarding commitment and scheduling; differences in partners' ages and developmental stages; differences in family situations; the common necessity of one or both partners moving to train at a new facility; and different skill levels when the partnership is formed.[41] Silby estimates that the lack of effective communication within dance and pairs teams is associated with a six-fold increase in the risk of ending their partnerships. Teams with strong skills in communication and conflict resolution, however, tend to produce more successful medalists at national championship events.[42]

Competition segments

Before the 2010–2011 figure skating season, there were three segments in ice dance competitions: the compulsory dance (CD), the original dance (OD), and the free dance (FD). In 2010, after many years of pressure from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to restructure competitive ice dance to follow the other figure skating disciplines, the ISU voted to change the competition format by eliminating the CD and the OD and adding the new short dance segment to the competition schedule.[43] According to the then-president of the ISU, Ottavio Cinquanta, the changes were also made because "the compulsory dances were not very attractive for spectators and television".[44] This new ice dance competition format was first included in the 2010–2011 season, incorporating just two segments: the short dance (renamed the rhythm dance, or RD in 2018) and the free dance.[43]

Rhythm dance

The RD is the first segment performed in all junior and senior ice dance competitions.[45] It combines many of the elements of the CD and the OD, retaining the characteristic set patterns of the CD, in which each dance team must perform the same two patterns of a set "pattern dance", providing "an essential comparison of the dancers' technical skills".[43] The ice dance team is judged on how well the pattern dance is integrated into the entire RD routine.[46] The RD must also include a short six-second lift, a set of twizzles, and a step sequence.[43][47]

The rhythms and themes of the RD are determined by the ISU prior to the start of each new season.[43][47] The RD should be "developed through skating skill and quality", instead of through "non-skating actions such as sliding on one knee"[48] or through the use of toe steps (which should only be used to reflect the dance's character and the music's nuances and underlining rhythm).[49] The RD must have a duration of two minutes and fifty seconds.[50]

The first RD in international competitions was performed by U.S. junior ice dancers Anastasia Cannuscio and Colin McManus, at the 2010 Junior Grand Prix Courchevel.[51] French ice dancers Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron hold the highest RD score of 92.73, which they achieved at the 2022 World Championships. They also hold the seven highest RD scores.[52]

Free dance

The free dance (FD) takes place after the rhythm dance in all junior and senior ice dance competitions.[53] The ISU defines the FD as "the skating by the couple of a creative dance program blending dance steps and movements expressing the character/rhythm(s) of the dance music chosen by the couple".[54] The FD must have combinations of new or known dance steps and movements, as well as required elements.[54] The program must "utilize the full ice surface,"[55] and be well-balanced. It must contain required combinations of elements (spins, lifts, steps, and movements), and choreography that express both the characters of the competitors and the music chosen by them. It must also display the skaters' "excellent skating technique"[54] and creativity in expression, concept, and arrangement.[56] The FD's choreography must reflect the music's accents, nuances, and dance character, and the ice dancers must "skate primarily in time to the rhythmic beat of the music and not to the melody alone".[54] For senior ice dancers, the FD must have a duration of four minutes; for juniors, 3.5 minutes.[56]

Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron hold the highest FD score of 137.09 points, which they achieved at the 2022 World Championships. They also hold the six highest recorded FD scores.[57][lower-alpha 2]

Compulsory dance

Before 2010, the compulsory dance (CD) was the first segment performed in ice dance competitions. The teams performed the same pattern around two circuits of the rink, one team after another, using the same step sequences and the same standardized tempo chosen by the ISU before the beginning of each season.[59][60] The CD has been compared with compulsory figures; competitors were "judged for their mastery of fundamental elements".[59] Early in ice dance history, the CD contributed 60% of the total score.[61]

The 2010 World Championships was the last event to include a CD (the Golden Waltz); Federica Faiella and Massimo Scali from Italy were the last ice dance team to perform a CD in international competition.[62]

Original dance

The OD was first added to ice dance competitions in 1967. It was called the "original set pattern dance"[63] until 1990, when it became known simply as the "original dance". The OD remained the second competition segment (sandwiched between the CD and the free dance) until the end of the 2009–2010 season.[61] Ice dancers were able to create their own routines, but they had to use a set rhythm and type of music which, like the compulsory dances, changed every season and was selected by the ISU in advance. The timing and interpretation of the rhythm were considered to be the most important aspects of the routine, and were worth the highest proportion of the OD score. The routine had a two-minute time limit and the OD accounted for 30% of the overall competition score.[64][65]

Canadian ice dancers Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir hold the highest OD score of 70.27 points, achieved at the 2010 World Championships.[66]

Competition elements

The ISU announces the list of required elements in the rhythm dance and free dance , and each element's specific requirements, each year. The following elements may be included: the dance lift, the dance spin, the step sequence, turn sequences (which include twizzles and one-foot turn sequences), and choreographic elements.[67]

- Dance lift: "a movement in which one of the partners is elevated with active and/or passive assistance of the other partner to any permitted height, sustained there and set down on the ice".[68] The ISU permits any rotation, position, and changes of position during a dance lift.[68] Dance lifts are delineated from pair lifts to ensure that ice dance and pair skating remain separate disciplines.[30] After the judging system changed from the 6.0 system to the ISU Judging System, dance lifts became more "athletic, dramatic and exciting".[69]

- Dance spin: "a spin skated by the Couple together in any hold".[70] It is "performed on the spot around a common axis on one foot with or without change(s) of foot by one or both partners".[70]

- Step sequence: "a series of prescribed or un-prescribed steps, turns and movements".[71]

- Turn sequences: a set of twizzles and a one foot turns sequence, or "Specified Turns performed on one foot by each partner simultaneously, in Hold or separately".[70]

- Choreographic elements: "a listed or unlisted movement or series of movement(s) as specified" by the ISU.[72]

Rules and regulations

Skaters must execute the prescribed elements at least once; any extra or unprescribed elements will not be counted in their score. In 1974, the ISU published the first judges' handbook describing what judges needed to look for during ice dance competitions.[73] Violations in ice dance include falls and interruptions, time, music, and clothing.

Falls and interruptions

According to ice dancer and commentator Tanith White, unlike in other disciplines wherein skaters can make up for their falls in other elements, falls in ice dance usually mean that the team will not win. White argues that falls are rare in ice dance, and since falls constitute interruptions, they tend to have large deductions because the mood of their program's theme is broken.[74] The ISU defines a fall as the "loss of control by a Skater with the result that the majority of his/her own body weight is on the ice supported by any other part of the body other than the blades; e.g. hand(s), knee(s), back, buttock(s) or any part of the arm".[75] The ISU defines an interruption as "the period of time starting immediately when the Competitor stops performing the program or is ordered to do so by the Referee, whichever is earlier, and ending when the Competitor resumes his performance".[76] A study conducted during a U.S. national competition including 58 ice dancers recorded an average of 0.97 injuries per athlete.[77]

In ice dance, teams can lose one point for every fall by one partner, and two points if both partners fall. If there is an interruption while performing their program, ice dancers can lose one point if it lasts more than ten seconds but not over twenty seconds. They can lose two points if the interruption lasts twenty seconds but not over thirty seconds, and three points if it lasts thirty seconds but not more than forty seconds. They can lose five points if the interruption lasts three or more minutes.[78] Teams can also lose points if a fall or interruption occurs during the beginning of an elevating moment in a dance lift, or as the man begins to lift the woman.[79] They can lose an additional five points if the interruption is caused by an "adverse condition" up to three minutes before the start of their program.[80]

Time

Judges penalize ice dancers one point up to every five seconds for ending their pattern dances too early or too late. Dancers can also be penalized one point for up to every five seconds "in excess of [the] permitted time after the last prescribed step" (their final movement and/or pose) in their pattern dances. If they start their programs between one and thirty seconds late, they can lose one point.[78] They can complete these programs within plus or minus ten seconds of the required times; if they cannot, judges can deduct points for finishing their program up to five seconds too early or too late. If they begin skating any element after their required time (plus the required ten seconds they have to begin), they earn no points for those elements. If the program's duration is "thirty (30) seconds or more under the required time range, no marks will be awarded".[50]

If a team performs a dance lift that exceeds the permitted duration, judges can deduct one point.[81] White argues that deductions in ice dance, in the absence of a fall or interruption, are most often due to "extended lifts",[74] or lifts that last too long.[74]

Music

All programs in each discipline of figure skating must be skated to music.[82] The ISU has allowed vocals in the music used in ice dance since the 1997–1998 season,[83] most likely because of the difficulty in finding suitable music without words for certain genres.[84][lower-alpha 3]

Violations against the music requirements have a two-point deduction, and violations against the dance tempo requirements have a one-point deduction.[81] If the quality or tempo of the music the team uses in their program is deficient, or if there is a stop or interruption in their music, for any reason, they must stop skating when they become aware of the problem "or at the acoustic signal of the Referee",[81] whichever occurs first. If any problems with the music happens within 20 seconds after they have begun their program, the team can choose to either restart their program or to continue from the point where they have stopped performing. If they decide to continue from the point where they stopped, they are continued to be judged at that point onward, as well as their performance up to that point.[81] If any of the mentioned problems occurs over 20 seconds after the start of their program, the team can resume their program from the point of the interruption or at the point immediately before an element, if the interruption occurred at the entrance to or during the element. The element must be deleted from the team's score and the team can repeat the deleted element when they resume their program. No deductions are made for interruptions caused by music deficiencies.[85]

The ISU provides the following definitions of musical terms used in the scoring of ice dance:[86]

- Beat – "A note defining the regular recurring divisions of a piece of music."

- Tempo – "The speed of music in Beats or Measures per minute."

- Rhythm – "The regularly repeated pattern of accented and unaccented Beats which gives the music its character."

- Measure (Bar) – "A unit of music which is defined by the periodic recurrence of the accent. Such units are of equal number of Beats."

- Strong Beat – "The first Beat of the Measure or group of two Measures supporting the skating count of the Rhythm."

- Weak Beat – "For Rhythms with a skating count on two Measures, the first Beat of the second Measure."

Clothing

The clothing worn by ice dancers at all international competitions must be "modest, dignified and appropriate for athletic competition—not garish or theatrical in design".[87] Rules about clothing tend to be more strict in ice dance; Juliet Newcomer from U.S. Figure Skating has speculated limits in the kind of costumes ice dancers chose were pushed farther during the 1990s and early 2000s than in the other disciplines, resulting in stricter rules.[88] Clothing can, however, reflect the character of ice dancers' chosen music. Their costumes must not "give the effect of excessive nudity inappropriate for the discipline".[87]

All men must wear trousers. Female ice dancers must wear skirts. Accessories and props on the costumes of both dancers are not allowed. The decorations on costumes must be "non-detachable";[87] judges can deduct one point per program if part of the competitors' costumes or decorations fall on the ice.[78] If there is a costume or prop violation, the judges can deduct one point per program. Judges penalize ice dance teams with a deduction to their scores if these guidelines are not followed, although exceptions to these clothing and costume restrictions may be announced by the ISU.[87] Costume deductions, however, are rare. According to Newcomer, by the time skaters get to a national or world championship, they have received enough feedback about their costumes and are no longer willing to risk losing points.[88]

Footnotes

- The Oxford Skating Society published a description and explanation of figures for hand-in-hand skating in 1836, well before it became popular.[6]

- After the 2018–2019 season, due to the change in grade of execution scores from −3 to +3 to −5 to +5, all statistics started from zero and all previous scores were listed as "historical".[58]

- The use of vocals was expanded to all disciplines starting in 2014.[83]

References

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 9

- Blakemore, Erin (12 December 2017). "The Man Who Invented Figure Skating Was Laughed Out of America". History.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Kestnbaum 2003, pp. xiv, 102.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 221.

- Hines 2006, p. 36.

- Hines 2006, p. 119.

- Hines 2006, p. 120.

- Hines 2006, p. 121.

- Hines 2006, p. 61.

- Hines 2006, p. 122.

- Hines (2006), p. 122

- Hines 2006, p. 123.

- Hines 2006, p. 124.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 222.

- Hines 2006, pp. 123–124.

- Hines 2011, p. 102.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 223.

- Hines 2006, pp. 173–174.

- Hines 2006, p. 174.

- Hines 2011, p. 120.

- Hines 2011, p. xxxi.

- Hines 2011, p. xxvi.

- Russell, Susan D. (5 January 2013). "Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov: The Heroes of Olympic Ice Dance". International Figure Skating. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Hines (2006), pp. 217–218

- Hines 2006, p. 240.

- "1984: British Ice Couple Score Olympic Gold". BBC. 14 February 1984. Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 228.

- Hines 2006, p. 239.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 239–240.

- Reiter, Susan (1 March 1995). "Ice Dancing: A Dance Form Frozen in Place by Hostile Rules". Dance Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Kestnbaum 2003, p. 244.

- Hines 2006, p. 242.

- Longman, Jere (13 February 1998). "The XVIII Winter Games: Figure Skating; Ice Dancers Battle It out in Quest for Credibility". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Hersh, Philip (18 February 1998). "Too Often, Ice Dance Judges Deserve Seats on Bench". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- "Judging on Thin Ice". The New York Times. 2 August 2002. p. A20. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Fowler, Geoffrey A.; Dvorak, Phred (23 January 2022). "Canada's Virtue, Moir Win Ice Dance Gold". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Wilner, Barry (6 December 2016). "The US Has Become the World Power in Ice Dance". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Canada's Tessa Virtue, Scott Moir Become Most Decorated Figure Skaters in Olympic History". ESPN.com. Associated Press. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Gabriella Papadakis, Guillaume Cizeron Win Figure Skating Worlds Ice Dance, Break Record". NBC Sports. Associated Press. 26 March 2022. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Silby 2018, p. 92.

- Silby 2018, pp. 92–93.

- Silby 2018, p. 93.

- "Partnered Ice Dancing Events". Ice Skating Information & Resources. San Diego Figure Skating Communications. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Kany, Klaus-Reinhold (9 July 2011). "The Short Dance Debate". International Figure Skating Magazine. No. August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 10

- "Dance Format 2011" (PDF). Havířov, Czech Republic: Kraso Club of Havířov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Zuckerman, Esther (14 February 2014). "A Quick GIF Guide to Ice Dance". The Atlantic Monthly. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 142

- S&P/ID 2021, p. 139

- S&P/ID 2022, p.80

- Brown, Mickey (28 August 2010). "Team USA Scores Four Medals at JGP Opener". icenetwork.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Progression of Highest Score: Ice Dance Rhythm Dance Score". isuresults.com. International Skating Union. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, pp. 9–10

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 143

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 144

- "Dance Format 2011" (PDF). Havířov, Czech Republic: Kraso Club of Havířov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Progression of Highest Score: Ice Dance Free Dance Score". isuresults.com. International Skating Union. 17 April 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Walker, Elvin (19 September 2018). "New Season New Rules". International Figure Skating. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Skate America: Tanith Belbin, Ben Agosto Second after Compulsory Dance". The Seattle Times. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Dimanno, Rosie (24 March 2010). "Virtue and Moir Happy to Say Ciao to Compulsory Dance". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Hines 2011, p. 12.

- "ISU Congress News". Ice Dance.com. 20 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Hines 2011, p. 91.

- "Skating: Ice dancing". BBC.com. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Wehrli-McLaughlin, Susi (2009). "Figure Skating". In Hanlon, Thomas W. (ed.). The Sports Rules Book (3rd ed.). Champlaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7360-7632-6.

- "Progression of Highest Score, Ice Dance, Original Dance Score". isuresults.com. International Skating Union. 13 August 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, pp. 142, 145

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 130

- Brannen, Sarah S. (13 July 2012). "Dangerous Drama: Dance Lifts Becoming 'Scary'". icenetwork.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 129

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 123

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 122

- Hines 2011, p. xxv.

- Lutz, Rachel (2 February 2018). "How to be a Better and Smarter Figure Skating Fan". NBC Olympics.com. NBC Universal. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, pp. 80–81

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 90

- Fortin, Joseph D.; Roberts, Diana (2003). "Competitive Figure Skating Injuries" (PDF). Pain Physician. 6 (3): 313–318. doi:10.36076/ppj.2003/6/313. PMID 16880878. S2CID 42526887. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 18

- "Communication No. 2393: Ice Dance". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 6 May 2021. p. 7. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ISU No. 2403, p. 68

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 19

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 11

- Hersh, Philip (23 October 2014). "Figure Skating Taking Cole Porter Approach: Anything Goes". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Clarey, Christopher (18 February 2014). "'Rhapsody in Blue' or Rap? Skating Will Add Vocals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- S&P/ID 2022, pp. 90–91

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 134

- S&P/ID 2022, p. 79

- Yang, Nancy (21 January 2016). "What Not to Wear: The Rules of Fashion on the Ice". MPR News. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

Works cited

- "Communication No. 2371: Ice Dance" (PDF). (ISU No. 2371) International Skating Union. 2 February 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Communication No. 2403: Summary of Results of Mail Voting on Proposals in Replacement of the 58th Ordinary Congress 2021". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2022 (ISU No. 2403).

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07286-4.

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6859-5.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- Silby, Caroline (2018). "Mental Skills Training: Psychological Considerations of Performance". In Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (eds.). The Science of Figure Skating. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–97. doi:10.4324/9781315387741-7. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2022". (S&P/ID 2022) International Skating Union. 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

External links

- Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean's free skate to Boléro, 1984 Olympics