Warkworth Castle

Warkworth Castle is a ruined medieval castle in Warkworth in the English county of Northumberland. The village and castle occupy a loop of the River Coquet, less than a mile from England's north-east coast. When the castle was founded is uncertain: traditionally its construction has been ascribed to Prince Henry of Scotland, Earl of Northumbria, in the mid-12th century, but it may have been built by King Henry II of England when he took control of England's northern counties. Warkworth Castle was first documented in a charter of 1157–1164 when Henry II granted it to Roger fitz Richard. The timber castle was considered "feeble", and was left undefended when the Scots invaded in 1173.

| Warkworth Castle | |

|---|---|

The castle's enclosure and keep | |

| Type | Motte and bailey castle |

| Location | Warkworth |

| Coordinates | 55°20′41″N 1°36′38″W |

| OS grid reference | NU24710575 |

| Area | Northumberland |

| Built | 12th century |

| Governing body | English Heritage |

| Owner | The 12th Duke of Northumberland |

| Official name | Warkworth Castle motte and bailey castle, tower keep castle and collegiate church |

| Designated | 9 July 1915 |

| Reference no. | 1011649 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Castle curtain walls with gateways, towers and attached buildings |

| Designated | 31 December 1969 |

| Reference no. | 1041690 |

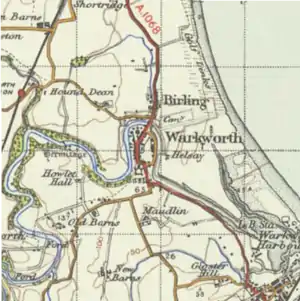

Location of Warkworth Castle in Northumberland | |

Roger's son Robert inherited and improved the castle. Robert was a favourite of King John, and hosted him at Warkworth Castle in 1213. The castle remained in the family line, with periods of guardianship when heirs were too young to control their estates. King Edward I stayed overnight in 1292 and John de Clavering, descendant of Roger fitz Richard, made the Crown his inheritor. With the outbreak of the Anglo-Scottish Wars, Edward II invested in castles, including Warkworth, where he funded the strengthening of the garrison in 1319. Twice in 1327 the Scots besieged the castle without success.

John de Clavering died in 1332 and his widow in 1345, at which point The 2nd Baron Percy of Alnwick took control of Warkworth Castle, having been promised Clavering's property by Edward III. Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, added the imposing keep overlooking the village of Warkworth in the late 14th century. The fourth earl remodelled the buildings in the bailey and began the construction of a collegiate church within the castle, but work on the latter was abandoned after his death. Although The 10th Earl of Northumberland supported Parliament during the English Civil War, the castle was damaged during the conflict. The last Percy earl died in 1670. In the mid-18th century the castle found its way into the hands of Hugh Smithson, who married the indirect Percy heiress. He adopted the surname "Percy" and founded the dynasty of the Dukes of Northumberland, through whom possession of the castle descended.

In the late 19th century, the dukes refurbished Warkworth Castle and Anthony Salvin was commissioned to restore the keep. The 8th Duke of Northumberland gave custody of the castle to the Office of Works in 1922. Since 1984 English Heritage has cared for the site, which is a Grade I listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

History

Early history

Although the settlement of Warkworth in Northumberland dates back to at least the 8th century, the first castle was not built until after the Norman Conquest.[1] The town and its castle occupied a loop of the River Coquet. The castle was built at the south end of the town, guarding the narrow neck of the loop. A fortified bridge also defended the approach to the town.[2] The surrounding lowland countryside was favourable for agriculture.[3] When the castle was founded and by whom is uncertain, though traditionally Prince Henry of Scotland, Earl of Northumberland, has been thought responsible.[4] With civil war in South West England, King Stephen of England needed to ensure northern England was secure. To this end, the Treaty of Durham in 1139 between Scotland and England ensured peace. Under the treaty Henry of Scotland became Earl of Northumbria in exchange for ceding control of the castles at Bamburgh and Newcastle to the English.[5] Without them Henry would have needed a new seat from which to exercise his authority, and a new castle at Warkworth may have met the requirement. However, charters show that Henry still controlled Bamburgh Castle after the treaty, and as Warkworth was a modest castle by contemporary standards it may be have been founded by someone else.[4] Henry died in 1152 and his son, Malcolm (crowned King of Scotland in 1153), inherited his lands. In 1157 Malcolm travelled to Peveril Castle in Derbyshire, where he paid homage to the new King of England, Henry II.[6] Malcolm surrendered England's northern counties to Henry, including the castles of Bamburgh, Carlisle, and Newcastle, and probably Appleby, Brough, Wark, and Warkworth,[7] though it is possible that Henry II founded Warkworth Castle in 1157 to secure his lands in Northumberland; other contemporary castles in the area were built for this purpose, for instance the one at Harbottle.[8]

The first mention of Warkworth Castle occurs in a charter of 1157–1164 from Henry II granting the castle and surrounding manor to Roger fitz Richard,[4] a member of a noble Norman family.[9] It has been suggested that this charter may have used the term castle to describe a high-status residence on the site, possibly dating from the Anglo-Saxon period, meaning Roger may have built the castle.[8] He owned lands across a wide area, and Warkworth may have been of little significance in the context of his other holdings. When the Scots invaded Northumberland in 1173, although Roger fitz Richard was in the county Warkworth Castle was not defended by its garrison. Its defences at the time were described as "feeble".[10] In 1174 Duncan II, Earl of Fife, raided Warkworth. The contemporary record does not mention the castle, and instead notes that Warkworth's inhabitants sought refuge in the church. When Roger fitz Richard died in 1178 his son and heir, Robert fitz Roger, was still a child. A guardian looked after the family estates until Robert came of age in 1191. He paid the Crown 300 marks in 1199 for confirmation of his ownership of Warkworth, including the castle. Substantial building work at Warkworth Castle is attributed to Robert. A favourite of King John, Robert hosted him at Warkworth Castle in 1213.[10]

Warkworth Castle continued to descend through the family line when Robert fitz Roger was succeeded by his son John in 1214, who was succeeded by his son Roger in 1240. Roger died in 1249 when his son Robert was one year old, and a guardian was appointed to care for the family's estates: William de Valence, half-brother of King Henry III. The castle, characterised by this time by the chronicler Matthew Paris as "noble",[10] remained under the guardianship of Valence until 1268, when it reverted to Robert fitz John.[11] King Edward I of England stayed at Warkworth Castle for a night in 1292. The English king was asked to mediate in a dispute over the Scottish throne and laid his own claim, leading to the Anglo-Scottish Wars. After the Scottish victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, Robert and his son, John de Clavering, were captured. They were subsequently released and in 1310 John assumed control of the family estates. A year later, John made arrangements so that on his death the king would receive all of his property.[12][13] Between roughly 1310 and 1330 the English struggled to deal with Scottish raids in northern England.[14] Such was the importance of large castles during the Scottish Wars that the Crown subsidised their maintenance and even construction. In 1319, King Edward II paid for a garrison for the castle of four men-at-arms and eight hobilars to enhance the existing force of twelve men-at-arms.[15] Ralph Neville was the keeper of Warkworth Castle in 1322. As he was married to John's daughter, Euphemia, Ralph may have hoped to inherit the Clavering estates, but that did not happen.[16] Twice in 1327 Scottish forces besieged the castle without success.[17]

Percy family

Around this time, the Percy family was becoming Northumberland's most powerful dynasty.[18] Henry de Percy, 2nd Baron Percy, was in the service of Edward III and was paid 500 marks a year in perpetuity in return for leading a company of men-at-arms. In exchange for the annual fee, in 1328 Percy was promised the rights to the Clavering estates. Parliament declared such contracts illegal in 1331, but after initially relinquishing his claim Percy was granted special permission to inherit. John de Clavering died in 1332 and his widow in 1345, at which point the family's estates became the property of the Percys.[13] While the Percys owned Alnwick Castle, which was considered more prestigious, Warkworth was the family's preferred home. Under the Percys a park was created nearby for hunting, and within the castle two residential blocks were created, described by historian John Goodall as "of unparalleled quality and sophistication in Northumberland".[18] The second baron died at Warkworth in 1352.[13]

In 1377 the fourth Baron Percy, also named Henry, was made the first Earl of Northumberland (becoming the first family from northern England to be granted an earldom)[14] in recognition of his extensive power in the march areas along the Anglo-Scottish border.[19] With a network of contacts and dependencies, the Percys were the pre-eminent family in northern England in the 14th century "for they have the hertes of the people by north and ever had", in the words of contemporaneous chronicler John Hardyng.[20] Henry Percy commissioned the building of the distinctive keep shortly after he was made Earl of Northumberland. Percy may have enhanced his main castle to compete with John of Gaunt, who rebuilt the nearby Dunstanburgh Castle, or with the House of Neville, a family becoming increasingly powerful in northern England and who undertook a programme of building at the castles of Brancepeth, Raby, Bamburgh, Middleham, and Sheriff Hutton.[19][21] Architectural similarities between Warkworth's keep, Bolton Castle, and the domestic buildings at Bamburgh Castle suggest that John Lewyn was the master mason responsible for building Warkworth's keep.[19] Earl Henry helped dethrone Richard II and replace him with Henry IV. The earl and his eldest son Henry "Hotspur" Percy fell out with the new king, and eventually rebelled. After Hotspur was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, his father fled to Warkworth.[22] The earl eventually went to York to submit to the king. He was arrested and the king attempted to install his own men at the castles of Alnwick, Langley Castle, Prudhoe, and Warkworth.[23] The earl's 14-year-old son claimed that he was loyal to the king but was not empowered to formally surrender the castle, and it remained under control of the Percys.[22] Henry was pardoned in 1404.[23]

Earl Henry rebelled again in 1405, this time joining the unsuccessful revolt of Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York. While Henry was fleeing north after the failed rebellion, his castles offered some resistance before submitting to royal forces. Warkworth itself was well-provisioned and the garrison initially refused to surrender. However, according to a letter written by Henry IV from Warkworth after its fall, after just seven shots from his cannon the defenders capitulated.[22] The castle was forfeited to the Crown, and was used by one of the King's sons, John, Duke of Bedford, who was appointed to rule the area.[24] It remained in the ownership of the Crown until Henry V restored it to the Percy family in 1416, and at the same time made the son of "Hotspur" Henry, another Henry Percy, second Earl of Northumberland. It is known that the second earl resided at Warkworth and undertook building work there, but it is now unclear for which parts he was responsible.[25]

The Percys supported the House of Lancaster during the Wars of the Roses, and the second earl and his successor – Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland – were killed at the battles of St Albans in 1455 and Towton in 1461 respectively.[25] The new king, Edward IV, issued an attainder against the family and their property was confiscated.[26] On 1 August 1464, as a result of suppressing Lancastrian rebellions in the north for the previous three years, the title of Earl of Northumberland was given to The 1st Marquess of Montagu, a Yorkist, and with it, the castle. During his tenure, he constructed a twenty-five-foot tall rectangular tower, built for defence, "with [arrow] slits in the three outer walls;" this is known as 'Montagu's Tower' to this day.[27] His brother, The 16th Earl of Warwick, used Warkworth as a base from which the Lancastrian-held castles of Northumberland – Alnwick, Bamburgh, and Dunstanburgh – were attacked and their sieges co-ordinated. In 1470 Edward IV returned the Percys' estates to the eldest son of the third earl, who was also called Henry Percy. A year later Henry was granted the earldom of Northumberland.[25] Some time after 1472 Henry remodelled the building of the bailey. He also planned to build a collegiate church within the castle, but the work was abandoned after his death. When the fourth earl was murdered in 1489, his son, Henry Algernon, inherited and maintained the castle. In the early 16th century Henry Percy, 6th Earl of Northumberland, was responsible for clearing the collegiate church founded by his grandfather, but left incomplete by the fifth earl. Thomas Percy, brother of the sixth earl, was executed for his role in the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. When Henry Percy died the next year without any sons, the family's property passed to the Crown.

In 1543 Sir William Parr, as warden of the Scottish marches decided to live at Warkworth and carried out repairs.[28] Although royal officers still used the castle, by 1550 it had fallen into disrepair. In 1557 the Percy estates were restored to the descendants of Thomas, and the nephew of the sixth earl, another Thomas Percy, was given the earldom. He began a programme of repairs at the castle, and in the process dismantled "the hall and other houses of office".[29]

The Rising of the North in 1569 saw Catholic nobles in northern England rebel against the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I. The Catholic Thomas Percy joined the rebellion[30] and supporters congregated at the castles of Alnwick and Warkworth. Sir John Forster, Warden of the March, ordered those inside to leave[29] and the castles were surrendered to his control.[31] During the conflict that followed, Warkworth remained under royal control.[29] Forster pillaged the castle, stripping it of its timbers and furnishings. The keep at least did not share in this fate,[30] but in April 1572 Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, bemoaned the treatment meted out to the Percy castles, writing to the queen's chief minister, "It is a great pity to see how Alnwick Castle and Warkworth are spoiled by him ... I am creditably informed that he means utterly to deface them both."[32] An attainder was issued against Thomas Percy so that when he came into English custody he was executed without trial on 22 August.[31] As a result, Percy's son was passed over,[32] but under the terms of the attainder his brother was allowed to inherit.[31] In 1574, Elizabeth granted Henry Percy permission to inherit the family's property and assume the title of 8th Earl of Northumberland.[32]

The castle formed the backdrop for several scenes in William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2. Another Henry Percy inherited the family estates in 1585 and assumed the title of 9th Earl of Northumberland. After the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, the earl was imprisoned for his connection with Thomas Percy, one of the plotters. Shortly before he was sentenced (he was fined £30,000 and held in the Tower of London), the earl leased Warkworth Castle to Sir Ralph Gray, who owned Chillingham Castle in Northumberland. Gray neglected the earl's building and allowed it to fall further into disrepair. The lead from the buildings in the bailey was sold in 1607 to alleviate the earl's financial problems. When James I visited in 1617 en route to Scotland, his entourage was angered by the sorry state of the castle.[33] With the unification of England and Scotland under a single ruler, the earls of Northumberland had no need for two great castles near the Anglo-Scottish border; they maintained Alnwick at the expense of Warkworth. In the first quarter of the 17th century, the keep was used to hold manor courts and for the laying out of oats.[34]

The details surrounding Warkworth Castle's role in the English Civil War are unclear, but the conflict resulted in further damage to the structure. Initially held by Royalist forces, the castle was still important enough that when the Scots invaded in 1644 they forced its surrender.[35] Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland, supported Parliament, which may have prevented the Scots from doing much damage to the castle.[34] Parliamentarian forces took over the castle in 1648; when they withdrew they removed the castle's doors and iron so that it could not be reused by the enemy. They may also have partially demolished some of the castle, and may be responsible for its present state. Algernon Percy unsuccessfully applied for compensation in 1649 for the damage.[35]

Dukes of Northumberland and present day

.jpg.webp)

The 11th Earl of Northumberland, the last Percy earl, died in 1670. Two years later his widow allowed the keep's materials to be reused to build Chirton Hall. A total of 272 cart-loads were taken from the keep.[35] Lord Northumberland's property passed to The 7th Duke of Somerset through marriage. In 1698, the owners decided not to renovate Warkworth Castle after the estimate to add battlements, floors and new windows came in at £1,600. Lady Elizabeth Seymour inherited the property from her father in 1750. Her husband, Hugh Smithson, changed his name to Hugh Percy, and the castle then descended through the Dukes of Northumberland, a dynasty he founded.[34]

During the 18th century the castle was allowed to languish. The south-west tower was falling apart and around 1752 part of the curtain wall east of the gatehouse was demolished (it was rebuilt towards the end of the century). The town and its historic ruins were by now attracting interest as a tourist destination, largely due to Bishop Thomas Percy's poem, The Hermit of Warkworth. In the mid 19th century, The 3rd Duke of Northumberland undertook some preservation work. His successor, The 4th Duke of Northumberland, contracted Anthony Salvin to restore the keep. The work undertaken between 1853 and 1858 was not as extensive as Salvin had planned, and was limited to partially refacing the exterior and adding new floors and roofs to two chambers, which became known as the Duke's Chambers, on the second floor.[36] The Duke occasionally used the chambers for picnics when he visited from Alnwick Castle. The 4th Duke funded excavations at the castle in the 1850s which uncovered the remains of the collegiate church within the bailey.[37]

In 1922, The 8th Duke of Northumberland granted custodianship of the castle to the Office of Works which had been made accountable for the guardianship of ancient monuments.[38] The Duke's Chambers remained under the direct control of the Percys. The Office of Works undertook excavations in the moat in 1924 and removed the custodian from the gatehouse. English Heritage, who now manage and maintain the site, succeeded as the castle's custodians in 1984, and three years later the Duke's Chambers were given over to their care.[39] The castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument,[40] a "nationally important" historic building and archaeological site which has been given protection against unauthorised change.[41] It is also a Grade I listed building (first listed in 1985)[42] and recognised as an internationally important structure.[43] The castle continues to be officially owned by the Percy family, currently being owned by the 12th Duke of Northumberland.

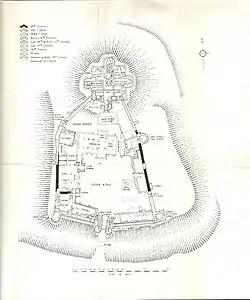

Layout

Warkworth Castle is an irregular enclosure. The keep is at the north end, overlooking the town, with the bailey to the south.[45] The current keep was built on an earlier mound, known as a motte.[46] The curtain wall of the bailey dates from the early 13th century. There are four towers: Carrickfergus Tower in the south-west corner, Montagu Tower in the south-east, a postern tower in the west wall (north of the kitchen), and Grey Mare's Tail Tower attached to the east wall. Against the east curtain wall was a stable. In the northern half of the bailey, aligned east–west, was an unfinished 15th-century collegiate church; it was cleared away in the early 16th century. Immediately west of the church was the kitchen, situated in the angle of the curtain wall as it changes from its north–south alignment and turns towards the keep. Along the west curtain wall, south of the kitchen, were the pantry, great hall, and withdrawing chambers. In the south-west was a chapel.[45] Apart from the north side, the castle was surrounded by a moat.[47]

Gatehouse

The gatehouse in the centre of the south curtain wall mostly dates from the 13th century. It was originally accessed via a drawbridge and visitors had to pass through two gates, one at either end of the passage, and a portcullis.[48] The semi-octagonal projections on either side of the gate passage are considered ornamental. Between the projections and above the gate were machicolations, openings for missiles to be hurled at attackers.[49] The rooms on either side of the passage were guardrooms.[47] The only remaining openings on the front are slits at ground level. Slits on the other sides of the gatehouse, and along the entrance passage, allowed the gatekeeper to watch people approaching and entering the castle. The structure underwent later alterations in the 19th and 20th centuries when it housed the castle's custodian; slits in the gatehouse's front may have been filled in.[48]

West range

The range along the western curtain wall dates from about 1480, when the fourth earl remodelled the bailey. The great hall was the social hub of the castle, where the household gathered to eat. The now-ruined 15th-century building replaced an earlier hall on the same site, dating from about 1200,[50] although some of the stone dates from the mid 12th century. The earl would have entered from the south from his connecting private chambers, and people of lower status through the Lion Tower.[51] Internally, it was split into two aisles of differing width. Both halls were heated by open hearths, two of which survive from the earlier hall. Opposite ends of the hall were for opposite ends of the social scale within the castle. The high end (next to the withdrawing chamber) was for the earl and his family, and the low end (next to the kitchen and other service rooms) for the rest of the household.[50] In the medieval period, the great hall was richly decorated with tapestries.[51]

The Lion Tower was the entrance to the north end of the great hall. Above the archway through the tower were displayed heraldic items, symbolic of the Percy earls' power. The lion at the bottom was the emblem of the earls. Though now much damaged, above the lion were the ancient arms of the family and the arms of the Lucy family, whose property the Percys had inherited in the 1380s. As the tower was entered from the bailey, on the right was a doorway leading to the incomplete collegiate church. To the left was the great hall, and beyond that, withdrawing chambers; to the right were the buttery, pantry, larder, and kitchen. Immediately north of the kitchen was a postern tower. Built around 1200, its upper floors were later reused for accommodation.[52] An entrance of lesser status than the main gatehouse, the gate's position next to the kitchen suggests it was a tradesmen's entrance, used for conveying supplies to the castle.[53]

The square Little Stair Tower was the entrance from the bailey to the withdrawing rooms south of the great hall.[54] At ground floor level there was a doorway in each of the tower's faces. Directly south of the east side of the tower was the castle's chapel. The northern door led to the great hall, and the western door to a cellar under the great chamber. There are only fragmentary remains of the spiral staircase. Above the passageway was a single room, of uncertain purpose: it may have been used as another chapel, a guest room,[55] or an antechamber where guests would wait before being admitted into the earl's presence.[54]

South of the great hall was a two-storey building containing withdrawing chambers, dating from around 1200. Narrow windows opening onto the bailey were original but have since been filled in.[56] The first floor was entirely occupied by the great chamber, furnished with a fireplace. In the south-west corner of the room was a door to a small room which was perhaps used as a safe. The ground floor was used as a cellar, through which the Carrickfergus Tower could be accessed.[51] The polygonal tower was also accessible through the great chamber at first floor level. Fitted with latrines and a fireplace,[56] it was an extension of the lordly accommodation provided by the great chamber.[51]

South and east

Montagu Tower in the south-east corner was probably built by John Neville, Lord Montagu, in the 15th century. Fitted with latrines and fireplaces, the upper floors provided accommodation, most likely for the more important members of the household. By the 16th century, the ground floor was used as a stable. The buildings against the south curtain wall between Montagu Tower and the gatehouse are of unknown purpose.[57] North of Montagu Tower, against the east curtain wall, are the ruins of stables which stood two storeys high. West of the stables was a wellhouse containing a stone-lined well some 18 metres (59 ft) deep. The Grey Mare's Tail Tower, probably built in the 1290s, has a slit in each of its five faces, offering views along the curtain wall.[58][59]

Keep

Goodall described Warkworth's keep as "a masterpiece of medieval English architecture". Built in the last quarter of the 14th century, it was probably designed by John Lewyn. It was laid out in the form of a Greek cross and originally it was crested with a battlement, and perhaps decorative statues. Around the top of the building survive carvings of angels carrying shields. A large lion representing the Percy's coat of arms overlooked the town from the north side of the keep. The lion and sculptures were probably originally painted and would have stood out from the rest of the building.[60] Archaeologist Oliver Creighton suggests that the rebuilding of the keep and other reconstruction work were meant to suggest the enduring lordship of the owners.[61] On top of the keep is a lookout tower, which would have been less prominent before the keep's roof was removed.[62]

Goodall suggests that the keep was used only for short periods, and the west range, including the great hall, was the lord's preferred residence for prolonged visits to Warkworth Castle.[63] The ground floor was used predominantly for storage of food and wine, but there was also a room with access to a basement chamber roughly 9 feet (2.7 m) square. This has variously been interpreted as an accounting room with a floor safe,[63] or guardroom with a dungeon dug into the floor.[62] In the keep's west wall was a postern through which stores would pass into the building.[64] Kitchens occupied the west side of the first floor and were connected via staircases to the stores immediately below.[63] In the south-east corner was a great hall, originally heated by a central hearth and spanning the height of the first and second floors. A chapel off the great hall led to a large formal room where the lord would meet guests.[65] The second floor was entirely domestic in nature, with bedrooms and withdrawing chambers.[66] In the 19th century, while the rest of Warkworth Castle was in ruins, the rooms of the second floor were re-roofed and occasionally used by the duke on visits.[67] At the centre of the keep was a lightwell with interior windows; at its foot was a tank for collecting rainwater used for cleaning.[64]

See also

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

- Warkworth Hermitage

References

- Notes

- Goodall 2006, pp. 33–34

- Creighton 2002, p. 43

- Emery 1996, p. 9

- Goodall 2006, p. 34

- Young 1978, p. 9

- Scott 2004

- Allen Brown 1959, p. 251

- Goodall 2006, pp. 34–35

- Mackenzie 1825, pp. 28–29

- Goodall 2006, p. 35

- Ridgeway 2004

- Goodall 2006, p. 36

- Bean 2004a

- Emery 1996, p. 14

- Goodall 2006, pp. 36–37

- Tuck 2004

- Hunter Blair 1970, p. 5

- Goodall 2006, p. 37

- Goodall 2006, p. 38

- Emery 1996, p. 14, n. 9

- Emery 1996, p. 17

- Goodall 2006, p. 39

- Bean 2004b

- Summerson 1995, p. 7

- Goodall 2006, p. 40

- Griffiths 2004

- History of Northumberland, Northumberland County History Committee, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1893, Vol. V, p.99

- State Papers Henry VIII, iv part 2 (London, 1836), p. 299.

- Goodall 2006, pp. 41–42

- Summerson 1995, p. 42

- Lock 2004

- Goodall 2006, p. 42

- Goodall 2006, p. 43

- Summerson 1995, p. 43

- Goodall 2006, p. 44

- Goodall 2006, pp. 44–46

- Summerson 1995, pp. 43–44

- Summerson 1995, p. 44

- Goodall 2006, p. 48

- "Warkworth Castle", Pastscape, English Heritage, retrieved 19 October 2011

- "Scheduled Monuments", Pastscape, English Heritage, retrieved 19 October 2011

- Castle Curtain Walls with Gateway, Towers and Attached Buildings, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 19 October 2011

- "Frequently asked questions", Images of England, English Heritage, archived from the original on 11 November 2007, retrieved 19 October 2011

- Hunter Blair 1970, p. 28

- Goodall 2006, p. 49

- Creighton 2002, p. 71

- Summerson 1995, pp. 14–15

- Summerson 1995, pp. 12–13

- Warkworth Castle motte and bailey castle, tower keep castle and collegiate church (PDF), Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, pp. 1–2, retrieved 29 October 2011

- Goodall 2006, p. 10

- Summerson 1995, p. 17

- Goodall 2006, pp. 5–7

- Summerson 1995, p. 19

- Goodall 2006, p. 11

- Summerson 1995, p. 16

- Goodall 2006, p. 12

- Goodall 2006, p. 13

- Summerson 1995, pp. 20–21

- Goodall 2006, p. 15

- Goodall 2006, p. 17

- Creighton 2002, pp. 71–72

- Emery 1996, p. 144

- Goodall 2006, pp. 17–19

- Summerson 1995, p. 27

- Goodall 2006, pp. 21–23

- Goodall 2006, p. 19

- Goodall 2006, p. 46

- Bibliography

- Allen Brown, Reginald (April 1959), "A List of Castles, 1154–1216", The English Historical Review, 74 (291): 249–280, doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxiv.291.249, JSTOR 558442

- Bean, J. M. W. (2004a), "Percy, Henry, second Lord Percy (1301–1352)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Bean, J. M. W. (2004b), "Percy, Henry, first earl of Northumberland (1341–1408)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Creighton, Oliver (2002), Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England, Sheffield: Equinox, ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8

- Emery, Anthony (1996), Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500, Volume I: Northern England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-49723-7

- Goodall, John (2006), Warkworth Castle and Hermitage, London: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-923-3

- Griffiths, R. A. (2004), "Percy, Henry, third earl of Northumberland (1421–1461)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Hunter Blair, Charles Henry; Honeyman, H.L. (1970), Warkworth Castle, Northumberland. Official Guidebook, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office

- Lock, Julian (2004), "Percy, Thomas, seventh earl of Northumberland (1528–1572)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Mackenzie, Eneas (1825), An historical, topographical, and descriptive view of the county of Northumberland: volume 2, Newcastle upon Tyne: Mackenzie and Dent

- Ridgeway, H. W. (2004), "Valence (Lusignan), William de, earl of Pembroke (d. 1296)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Scott, W. W. (2004), "Malcolm IV (1141–1165), king of Scots", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Summerson, Henry (1995), Warkworth Castle, London: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-498-X

- Tuck, Anthony (2004), "Neville, Ralph, fourth Lord Neville (c.1291–1367)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Young, Alan (1978), William Cumin: Border politics and the Bishopric of Durham, 1141–1144, York: Borthwick Publications, ISBN 978-0-900701-46-7

Further reading

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1999), Historic Sites of Northumberland and Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunderland: Albion Press, ISBN 978-0-9525122-1-9