You Only Live Twice (novel)

You Only Live Twice is the eleventh novel in Ian Fleming's James Bond series of stories. It was first published by Jonathan Cape in the United Kingdom on 26 March 1964 and sold out quickly. It was the last Fleming novel published in his lifetime. It is the concluding chapter in what is known as the "Blofeld Trilogy" after Thunderball and On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

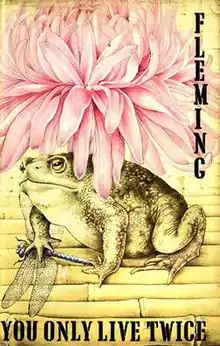

First edition cover | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Published | 26 March 1964 (Jonathan Cape) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 260 |

| Preceded by | On Her Majesty's Secret Service |

| Followed by | The Man with the Golden Gun |

The story starts eight months after the murder of Tracy Bond, which occurred at the end of the previous novel, On Her Majesty's Secret Service. James Bond is drinking and gambling heavily and making mistakes on his assignments when, as a last resort, he is sent to Japan on a semi-diplomatic mission. Whilst there he is challenged by the head of the Japanese Secret Service to kill Dr. Guntram Shatterhand. Bond realises that Shatterhand is Ernst Stavro Blofeld and sets out on a revenge mission to kill him and his wife, Irma Bunt.

The novel deals on a personal level with the change in Bond from a depressed man in mourning, to a man of action bent on revenge, to an amnesiac living as a Japanese fisherman. Through the mouths of his characters, Fleming also examines the decline of post-World War II British power and influence, notably in relation to the United States. The book was popular with the public, with pre-orders in the UK totalling 62,000; critics were more muted in their reactions, generally delivering mixed reviews of the novel.

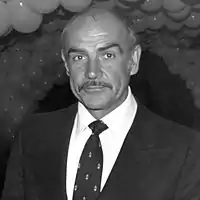

The story was serialised in the Daily Express newspaper and Playboy magazine, and also adapted for comic strip format in the Daily Express. In 1967, it was released as the fifth entry in the Eon Productions James Bond film series, starring Sean Connery as Bond. The novel has also been adapted as a radio play and broadcast on the BBC.

Plot

After the wedding-day murder of his wife, Tracy (see On Her Majesty's Secret Service), Bond begins to let his life slide, drinking and gambling heavily, making mistakes and turning up late for work. His superior in the Secret Service, M, had been planning to dismiss Bond, but decides to give him a last-chance opportunity to redeem himself by assigning him to the diplomatic branch of the organisation. Bond is subsequently re-numbered 7777 and handed an "impossible" mission: convincing the head of Japan's secret intelligence service, Tiger Tanaka, to share a decoding machine codenamed Magic 44 and so allow Britain to obtain information from encrypted radio transmissions made by the Soviet Union. In exchange, the Secret Service will allow the Japanese access to one of their own information sources.

Bond is introduced to Tanaka—and to the Japanese lifestyle—by an Australian intelligence officer, Dikko Henderson. When Bond raises the purpose of his mission with Tanaka, it transpires that the Japanese have already penetrated the British information source and Bond has nothing left to bargain with. Instead, Tanaka asks Bond to kill Dr. Guntram Shatterhand, who operates a politically embarrassing "Garden of Death" of poisonous plants in a rebuilt ancient castle on the island of Kyushu; people flock there to commit suicide. After examining photos of Shatterhand and his wife, Bond discovers that the couple are actually Tracy's murderers, Ernst Stavro Blofeld and Irma Bunt. Bond gladly takes the mission, keeping his knowledge of Blofeld's identity a secret so that he can exact revenge for his wife's death. Made up and trained by Tanaka, and aided by former Japanese film star Kissy Suzuki, Bond attempts to live and think as a mute Japanese coal miner in order to penetrate Shatterhand's castle. Tanaka renames Bond "Taro Todoroki" for the mission.

After infiltrating the Garden of Death and the castle where Blofeld spends his time dressed in the costume of a Samurai warrior, Bond is captured and Bunt identifies him as a British secret agent and not a Japanese coal miner. After surviving a near execution, Bond exacts revenge on Blofeld in a duel, Blofeld armed with a sword and Bond with a wooden staff. Bond eventually kills Blofeld by strangling him with his bare hands in a fit of violent rage, then blows up the castle. Upon escaping, he suffers a head injury, leaving him an amnesiac living as a Japanese fisherman with Kissy, while the rest of the world believes him dead; his obituary appears in the newspapers.

While Bond's health improves, Kissy conceals his true identity to keep him forever to herself. Kissy eventually sleeps with Bond and becomes pregnant, and hopes that Bond will propose marriage after she finds the right time to tell him about her pregnancy. Bond reads scraps of newspaper and fixates on a reference to Vladivostok, making him wonder if the far-off city is the key to his missing memory; he tells Kissy he must travel to Russia to find out.

Characters and themes

The central character in the novel is James Bond himself and the book's penultimate chapter contains his obituary, purportedly written for The Times by M. The obituary provides a number of biographical details of Bond's early life, including his parents' names and nationalities.[1] Bond begins You Only Live Twice in a disturbed state, described by M as "going to pieces", following the death of his wife Tracy eight months previously.[2] Academic Jeremy Black points out that it was a very different Bond to the character who lost Vesper Lynd at the end of Casino Royale.[3] Given a final chance by M to redeem himself with a difficult mission, Bond's character changes under the ministrations of Dikko Henderson, Tiger Tanaka and Kissy Suzuki.[4] The result, according to Benson, is a Bond with a sense of humour and a purpose in life.[1] Benson finds the transformation of Bond's character to be the most important theme in the novel: that of rebirth.[2] This is suggested in Bond's attempt at a Haiku, written in the style of Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō:

You only live twice:

Once when you are born

And once when you look death in the face— You Only Live Twice, Chapter 11

The rebirth in question is that of Bond, transformed from the heavy drinker mourning his wife at the beginning of the book to a man of action and then, after the death of Blofeld, becoming Taro Todoroki, the Japanese partner of Kissy Suzuki.[2] While Bond is in his action phase, Benson sees Fleming's writing becoming allegorical and epic, using Bond as a symbol of good against the evil of Blofeld.[5] As in Goldfinger and The Spy Who Loved Me, Bond is referred to as St George in his fight against the dragon, this time by Tiger Tanaka, who says that "it would make the subject for a most entertaining Japanese print."[5]

According to the author of continuation Bond novels, Raymond Benson, Kissy Suzuki is "a most appealing heroine" and "apparently loves Bond very much."[1] Apart from being the mother of Bond's unborn child at the end of the book, Suzuki also acts as a "cultural translator" for Bond, helping explain the local traditions and customs; Quarrel had the same function in Live and Let Die and Dr. No.[6] Academic Christoph Lindner identifies Tiger Tanaka as one of Fleming's characters with morals closer to those of traditional villains, but who act on the side of good in support of Bond; others of this type have included Darko Kerim (From Russia, with Love), Marc-Ange Draco (On Her Majesty's Secret Service) and Enrico Colombo ("Risico").[7]

Blofeld makes his third appearance in the Bond series in You Only Live Twice[8] and Benson notes that on this occasion he is quite mad and egocentric in his behaviour;[9] Tanaka refers to him as "a devil who has taken human form".[10] Comentale, Watt and Willman note that Fleming, through Bond, parallels Blofeld with Caligula, Nero and Hitler, and that this exemplifies Blofeld's actions as being on "a titanic scale", as much of the criminal action was throughout the Bond series.[11] Lindner echoes this, noting that the crimes perpetrated are not against individuals per se, but entire nations or continents.[12]

Much in the novel concerns the state of Britain in world affairs. Black points out that the reason for Bond's mission to Japan is that the US did not want to share intelligence regarding the Pacific, which it saw as its "private preserve". As Black goes on to note, however, the defections of four members of MI6 to the Soviet Union had a major impact in US intelligence circles on how Britain was viewed.[3] The last of the defections was that of Kim Philby in January 1963,[13] while Fleming was still writing the first draft of the novel.[14] Black contends that the conversation between M and Bond allows Fleming to discuss the decline of Britain, with the defections and the 1963 Profumo affair as a backdrop.[15]

The theme of Britain's declining position in the world is also dealt with in conversations between Bond and Tanaka, Tanaka voicing Fleming's own concerns about the state of Britain in the 1950s and early 60s.[16] Tanaka accuses Britain of throwing away the empire "with both hands";[17] this would have been a contentious situation for Fleming, as he wrote the novel as the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation was breaking out in December 1962, a direct challenge to British interests in the region.[15] Fleming's increasingly jaundiced views on America appear in the novel too,[18] through Bond's responses to Tiger's comments, and they reflect on the declining relationship between Britain and America: this is in sharp contrast to the warm, co-operative relationship between Bond and Leiter in the earlier books.[15]

Background

You Only Live Twice is the twelfth book (the eleventh novel) of Fleming's Bond series and the last book completed by Fleming before his death.[19] The story is the third part of the Blofeld trilogy,[8] coming after Thunderball, where SPECTRE is introduced, and On Her Majesty's Secret Service, where Blofeld is involved in the murder of Bond's wife. You Only Live Twice was the last book by Fleming that was published in his lifetime:[5] he died five months after the UK release of the novel.[20] It was written in January and February 1963 in Jamaica at Fleming's Goldeneye estate.[14] The original manuscript was 170 pages long and the least revised of all Fleming's novels,[14] with a mood that is dark and claustrophobic,[19] reflecting Fleming's own increasing melancholia.[3] The story was written after the film version of Dr. No was released in 1962, and Bond's personality was somewhat skewed towards the screen persona rather than simply to Fleming himself;[21] Sean Connery's filmic depiction of Bond affected the book version, with You Only Live Twice giving Bond a sense of humour and Scottish antecedents that were not present in the previous stories,[22] although Fleming himself was part Scottish. Correspondence dating back to 1960 shows that Fleming contacted a Scottish nobleman to help develop Bond's family history, in particular seeking a Scottish "Bond" family line.[23]

Fleming's first trip to Japan was as part of the Thrilling Cities trip undertaken for The Sunday Times in 1959,[24] although his visit only lasted for three days.[8] He returned in 1962 and was accompanied on his trip round the country by Australian friend Richard Hughes and Tiger Saito, both journalists. In You Only Live Twice, these two characters became Dikko Henderson and Tiger Tanaka, respectively. Hughes was also the model for "Old Craw" in John le Carré's The Honourable Schoolboy.[24]

The novel contains a fictional obituary of Bond, purportedly published in The Times, which provided details of Bond's early life,[25] although many of these were Fleming's own traits. These included Bond's expulsion from Eton College, which was part of Fleming's own history.[26] As with a number of the previous Bond stories, You Only Live Twice used names of individuals and places that were from Fleming's past. Bond's mother, Monique Delacroix, was named after two women in Fleming's life: Monique Panchaud de Bottomes, a Swiss girl from Vich in the canton of Vaud who Fleming was engaged to in the early 1930s,[27] with Delacroix taken from Fleming's own mother, whose maiden name was Ste Croix Rose.[28] Bond's aunt was called Charmian Bond: Charmian was the name of Fleming's cousin who married Richard Fleming, Ian's brother.[28] Charmian's sister was called "Pet" which, when combined with the Bottom from Monique Panchaud de Bottomes, gives Pett Bottom, where Charmian lives.[28] Pett Bottom is also the name of a real place which amused Fleming when he stopped for lunch after a round of golf at Royal St George's Golf Club, Sandwich.[28] In the summer of 1963, shortly after completing the book, Fleming went to Montreux to visit writer Georges Simenon and tried to see Monique to reveal her part in his new book, but she refused to meet him. Although she did later find out about it and once told her son from her subsequent marriage to Velcro inventor George de Mestral, "By the way, you have a brother – his name is James Bond."[29]

Ernst Stavro Blofeld's name partially comes from Tom Blofeld, a Norfolk farmer and a fellow member of Fleming's club Boodle's, who was a contemporary of Fleming's at Eton.[30] Tom Blofeld's son is Henry Blofeld, a sports journalist, best known as a cricket commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio.[31] For Blofeld's pseudonym in the novel, Dr. Guntram Shatterhand, Fleming uses the name of an old café he had seen in Hamburg in 1959 ("Old Shatterhand", a fictional character penned in a series of Western stories along with Winnetou by German writer Karl May).[28] The characterisation of him dressed as a samurai was taken from the sketch Fleming had come up with thirty five years earlier for a character called Graf Schlick.[19]

Release and reception

... high-flown and romanticized caricatures of episodes in the career of an outstanding public servant.

—Fleming, Bond's obituary

You Only Live Twice, Chapter 21

You Only Live Twice was published in the UK on 16 March 1964,[32] by Jonathan Cape and cost sixteen shillings.[33] There were 62,000 pre-orders for the book,[34] a significant increase over the 42,000 advance orders for the hardback first edition of On Her Majesty's Secret Service.[35] Richard Chopping, cover artist for The Spy Who Loved Me, was engaged for the design.[32] On 17 July 1963, Michael Howard of Jonathan Cape had written to Chopping about the artwork, saying: "I have had a talk with Ian about the ideas for the ingredients of this design. He is very much in favour of the toad ... but with a suitable array of oriental embellishrangment, i.e. toad plus Japanese flower arrangements, which he thinks should be sitting in a suitable piece of Japanese pottery, perhaps ornamented with a dragon motif. If you could manage a pink dragonfly sitting on the flowers, and perhaps just one epicanthic eye peering through them he thinks that will be just splendid!"[36] Chopping's fee rose to 300 guineas for the cover[37] from the 250 guineas he received for The Spy Who Loved Me.[38]

You Only Live Twice was published in the United States by New American Library in August 1964;[32] it was 240 pages long and cost $4.50.[39]

Reviews

Cyril Connolly, reviewing You Only Live Twice in The Sunday Times, wrote that Fleming's latest book was "reactionary, sentimental, square, the Bond-image flails its way through the middle-brow masses, a relaxation to the great, a stimulus to the humble, the only common denominator between Kennedy and Oswald".[40] The critic for The Times was largely unimpressed with You Only Live Twice, complaining that "as a moderate to middling travelogue what follows will just about do ... the plot with its concomitant sadism does not really get going until more than half way through".[41] In contrast to the previous novels, The Times continued, "though Mr. Fleming's macabre imagination is as interesting as ever, some of the old snap seems to have gone".[41] Dealing with the cliffhanger ending to the story, the reviewer wrote that "Mr. Fleming would keep us on tenterhooks, but at this rate of going even his most devoted admirers will free themselves before very long."[41]

The critic for The Spectator felt that "Ian Fleming has taken a hint from films of his books and is now inclined to send himself up. I am not at all sure that he is wise",[40] while The Belfast Telegraph considered that Fleming was "still in a class of his own."[40] The Bookman declared that You Only Live Twice "must rank among the best of the Bonds".[32] Malcolm Muggeridge, writing in Esquire magazine, disagreed, writing that "You Only Live Twice has a decidedly perfunctory air. Bond can only manage to sleep with his Japanese girl with the aid of colour pornography. His drinking sessions seem somehow desperate, and the horrors are too absurd to horrify ... it's all rather a muddle and scarcely in the tradition of Secret Service fiction. Perhaps the earlier novels are better. If so, I shall never know, having no intention of reading them."[40]

Maurice Richardson, in The Observer, thought You Only Live Twice "though far from the best Bond, is really almost as easy to read as any of them".[42] He was critical of a number of aspects, saying that the "narrative is a bit weak, action long delayed and disappointing when it comes but the surround of local colour ... has been worked over with that unique combination of pubescent imagination and industry which is Mr. Fleming's speciality."[42] In The Guardian, Francis Iles wrote that "I think he [Fleming] must be getting tired of the ineffable James Bond and perhaps even of writing thrillers at all".[43] Iles reasoned that "of the 260 pages of You Only Live Twice ... only 60 are concerned with the actual business of a thriller",[43] and his enjoyment was further diminished by what he considered "the grossness of Bond's manners and his schoolboy obscenities".[43]

Peter Duval Smith, in the Financial Times, was in two minds about the book, believing on the one hand that "the background is excellent ... Mr. Fleming has caught the exact 'feel' of Japan",[44] and on the other that You Only Live Twice "is not really a success and it's Bond's fault mainly. He just doesn't add up to a human being".[44] Maggie Ross, in The Listener, was also a little dissatisfied, writing that the novel can be read as a thriller and, "if interest flags, as it may do, the book can be treated as a tourist guide to some of the more interesting parts of Japan."[45] She went on to say that "since not very much in the way of real excitement happens until the latter half of the book, perhaps it is better to ignore the whole thing".[45]

Robert Fulford, in the Toronto-based magazine Maclean's, noted that "the characteristic which makes Fleming appear so silly also helps make him so popular: his moral simplicity. When we read James Bond we know whose side we are on, why we are on that side and why we are certain to win. In the real world that is no longer possible."[40] Charles Poore, writing in The New York Times, noted that Bond's mission "is aimed at restoring Britain's pre-World War II place among the powers of the world. And on that subject, above all others, Ian Fleming's novels are endlessly, bitterly eloquent."[39] The Boston Globe's Mary Castle opined that the agent's trip was "Bond's latest and grimmest mission",[46] which she called "Escapism in the Grand Manner".[46]

Adaptations

- Daily Express serialisation (1964)

You Only Live Twice was adapted for serialisation in the Daily Express newspaper on a daily basis from 2 March 1964 onwards.[33]

- Playboy serialisation (1964)

You Only Live Twice was serialised in the April, May and June 1964 issues of Playboy magazine.[47]

- Comic strip (1965–1966)

Ian Fleming's novel was adapted as a daily comic strip published in the Daily Express newspaper, and syndicated worldwide. The adaptation, written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky, ran from 18 May 1965 to 8 January 1966.[48] It was the final James Bond strip for Gammidge, while McClusky returned to illustrating the strip in the 1980s.[48] The strip was reprinted by Titan Books in The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2, published in 2011.[49]

- You Only Live Twice (1967)

In 1967, the book was adapted into the fifth film in the Eon Productions series, starring Sean Connery as Bond[50] and screenplay by longtime Fleming friend Roald Dahl.[51] Only a few elements of the novel and a limited number of Fleming's characters survive into the film version.[52] One notable aspect is, while the book features the final appearance of Blofeld in the novels, the film marks the character's first full on-screen appearance and launches a trilogy of films in which Blofeld is the central villain.

- Radio adaptation (1990)

In 1990, the novel was adapted into a 90-minute radio play for BBC Radio 4 with Michael Jayston playing James Bond. The production was repeated a number of times between 2008 and 2013.[53]

- No Time To Die (2021)

The 25th EON Bond film makes use of multiple elements of this Fleming novel. The main villain, Lyutsifer Safin, has a poisoned garden in Japan. Bond strangles Blofeld in an act of rage while saying "Die, Blofeld, die!", although in the film this does not directly kill him. Bond becomes a father, although unlike in the novel, the child is known to him. The Jack London quote referenced by Mary Goodnight in the novel is quoted by M at the end of the film: "The function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days trying to prolong them. I shall use my time". The quote is also delivered in the same context as the novel.

See also

- Outline of James Bond

References

- Benson 1988, p. 138.

- Benson 1988, p. 137.

- Black 2005, p. 61.

- Benson 1988, p. 138-139.

- Benson 1988, p. 136.

- Comentale, Watt & Willman 2005, p. 168.

- Lindner 2009, p. 39.

- Black 2005, p. 60.

- Benson 1988, p. 139.

- Lindner 2009, p. 42.

- Comentale, Watt & Willman 2005, p. 227.

- Lindner 2009, p. 79.

- Clive 2017.

- Benson 1988, p. 24.

- Black 2005, p. 62.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 113.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 200-201.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 187.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 222.

- "Obituary: Mr. Ian Fleming". The Times. 13 August 1964. p. 12.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 75.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 205.

- Helfenstein 2009.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 222-223.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 58.

- Macintyre 2008, p. 33.

- "Affairs of the Heart – Ian Fleming". Ian Fleming Publications. 12 September 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- Marti, Michael; Wälty, Peter (7 October 2012). "Und das ist die Mama von James Bond". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 117.

- Macintyre, Ben (5 April 2008a). "Bond – the real Bond". The Times. p. 36.

- Benson 1988, p. 26.

- Fleming, Ian (2 March 1964). "James Bond: You Only Live Twice". Daily Express. p. 6.

- Lycett 1996, p. 437.

- Lycett 1996, p. 419.

- Turner 2016, 3687.

- Lycett 1996, p. 426.

- Lycett 1996, p. 390.

- Poore, Charles (22 August 1964). "Books of the Times". The New York Times.

- Chancellor 2005, p. 223.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 19 March 1964. p. 16.

- Richardson, Maurice (15 March 1964). "Bondo-san and Tiger Tanaka". The Observer. p. 27.

- Iles, Francis. "Criminal Records". The Guardian. p. 8.

- Duval Smith, Peter (26 March 1964). "Could Do Better". Financial Times. p. 28.

- Ross, Maggie (26 March 1964). "New Novels". The Listener. p. 529.

- Castle, Mary (6 September 1964). "Thrills and Chills Dept". The Boston Globe. p. 43.

- Lindner 2009, p. 92.

- Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- McLusky et al. 2011, p. 76.

- Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 81.

- Collin, Robbie (18 February 2021). "'Sean Connery? He never stood anyone a round': Roald Dahl's love-hate relationship with Hollywood". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 72.

- "James Bond – You Only Live Twice". BBC Radio 4 Extra. BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Clive, Nigel (2017). "Philby, Harold Adrian Russell (Kim) (1912–1988)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40699. Retrieved 25 October 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Comentale, Edward P; Watt, Stephen; Willman, Skip (2005). Ian Fleming & James Bond: the cultural politics of 007. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21743-1.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-040-5.

- Helfenstein, Charles (2009). The Making of on Her Majesty's Secret Service. London: Spies Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9844126-0-0.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Lawrence, Jim; Fleming, Ian; Horak, Yaroslav (2011). The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-432-9.

- Turner, Jon Lys (2016). The Visitors' Book: In Francis Bacon's Shadow: The Lives of Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller (Kindle ed.). London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-47212-168-4.

External links

Quotations related to You Only Live Twice at Wikiquote

Quotations related to You Only Live Twice at Wikiquote- You Only Live Twice at Faded Page (Canada)

- Official Website of Ian Fleming Publications